Abstract

Background and purpose

The debate over the fact that experimental drugs proposed for the treatment of stroke fail in the translation to the clinical situation, has attracted considerable attention in the literature. In this context, we present a retrospective pooled analysis of a large dataset from pre-clinical studies, in order to examine the effects of early versus late administration of intravenous recombinant tissue type plasminogen activator (rt-PA).

Methods

We collected data from 26 individual studies from 9 international centers (13 researchers, 716 animals) that compared rt-PA to controls, in a unique mouse model of thromboembolic stroke induced by an in situ injection of thrombin into the middle cerebral artery. Studies were classified into early (<3h) versus late (≥3h) drug administration. Final infarct volumes, assessed by histology or MRI, were compared in each study and the absolute differences were pooled in a random-effect meta-analysis. The influence of time of administration was tested.

Results

When compared to saline controls, early rt-PA administration was associated with a significant benefit (absolute difference = −6.63 mm3; 95%CI, −9.08 to −4.17; I2=76%) whereas late rt-PA treatment showed a deleterious effect (+5.06 mm3; 95%CI, +2.78 to +7.34; I2=42%, Pint<0.00001). Results remained unchanged following subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

Our results provide the basis needed for the design of future pre-clinical studies on recanalization therapies using this model of thromboembolic stroke in mice. The power analysis reveals that a multi-center trial would require 123 animals per group instead of 40 for a single center trial.

Keywords: Stroke, thrombolysis, preclinical stroke model

Introduction

Intravenous recombinant tissue type plasminogen activator (rt-PA), administered within 4.5h after stroke onset, is the only pharmacological treatment approved for acute ischemic stroke.1 However, it can only be administered to a minority of patients, achieves early arterial recanalization in less than 50% of cases, and has deleterious effects, including intracerebral hemorrhage; thus underlying the need for developing new acute strategies to be employed for the treatment of stroke.

Testing potential acute therapies in animal models is presently the most common strategy for development of new drugs for use in stroke. However, many approaches that showed efficacy in experimental stroke models, have either not been translated or failed when tested in clinical trials.2–6 This “translational roadblock” is commonly attributed to inherent weaknesses of preclinical studies that include, lack of clinical relevance of the stroke models,7,8 monocentric design, and small sample sizes.9 Thus, improving the validity and reproducibility of pre-clinical studies is warranted. Some authors advocate for the use of multicenter preclinical studies,10 and much effort was expended to develop new experimental models which mimic more closely the pathophysiology of stroke.11–13 Reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analysis of preclinical stroke studies from groups such as CAMARADES (Collaborative Approach to Meta-Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies; http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/camarades/default.htm - about) has increased.14–18 These approaches allow one to take into account the fact that individual studies may have used small sample sizes, and to compare data from more than one type of experimental stroke model.

In 2007, we developed a thromboembolic model of stroke in mice,12 that appears physiologically relevant and is now used by several groups to evaluate the effects of rt-PA either alone, or where necessary in combination with putative neuroprotective drugs.19–21 However, no large-scale validation of this model is available so far. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of early (< 3 h) and late (≥ 3 h) rt-PA administration in this stroke model in a retrospective pooled analysis of individual data from 9 international research centers.

Material & Methods

Selection criteria, search strategy, and data collection

Eligible studies for inclusion in this analysis were those that (1) used the thromboembolic stroke model described below according to a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP), (2) compared human rt-PA (Alteplase®) treatment alone to a control saline group, whatever the time-window of treatment after stroke onset or the dose of rt-PA used, and (3) evaluated efficacy on lesion volumes measured either by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or histology at, 24 h post-stroke onset. There were no restrictions on the strain of mice, or the dose of rt-PA used, during the protocol. Relevant studies were identified by a systematic search of the scientific literature of studies published from 2007 to 2013, and by collecting data from studies that we were aware of but not yet published. Thus, at the time of this meta-analysis, 9 international centers were identified and made their data available for this study. The inclusion criterion was a reduction of cerebral blood velocity to at least 60% of the baseline value before initiating treatment. No animals were excluded from the final analysis due premature death — related to technical complication — nor as a result of the drug itself, during or after administration. However, 85 animals were excluded from the global analysis (47 saline controls, 15 early and 31 late rt-PA-treated) because either an excessively high-dose of thrombin was used (3 UI) in non-compliance with the SOP or, an unmatched control group was used (i.e.,early saline vs late rt-PA-treated). For each study, we collected raw data which included the identification of each experimenter, mouse strain, gender, experimental treatment (including the dose of thrombin used), the dose of rt-PA administered, the time of administration of rt-PA after stroke onset, and the lesion volume (see Supplemental Table I). Early rt-PA administration was defined when the injection was performed within the first 3 h and late rt-PA administration was defined when rt-PA was injected after 3 h, post stroke onset.

Animals and ethics

Depending on the research centers, experiments were performed on groups of male mice (Swiss or C57/Bl6) weighing 25-40g and 20-30g, respectively (Charles Rivers Laboratory; Janvier Lab, Jackson Labs, Harland labs and the Centre Universitaire de Resources Biologiques of Caen - Normandie Universitie). All animals were housed under standard conditions with a 12 h light/dark cycle and access to food and water ad libitum.

Studies were performed in accordance with the mandate of either the European Community Council Directive of 24th November 1986 (86/609/EEC) or the NIH guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal procedures were approved by the regional Ethical Committees for Laboratory Animal Experiments for each center. All efforts were made to minimize the possible suffering of the animals.

Thromboembolic stroke model

Cerebral ischemia was induced as described previously12 and all centers followed a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP; supplemental material and methods). In brief, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction 4-5%, maintenance 1–2%) in 8 out of 9 centers. In one center, mice were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine mixture (i.p., 50 mg/kg and 6 mg/kg, respectively). A small craniotomy was performed, the dura was excised, and the middle cerebral artery (MCA) exposed. The pipette (glass micro-pipette, tip size 30-50μm) was introduced into the lumen of the artery and 1 or 2 μL of murine α-thrombin (Haematologic Technologies Inc., USA) was injected to induce a clot, in situ. One center used human α-thrombin (0.75UI/μL; Haematologic Technologies Inc., USA). Different doses of thrombin were used by the different centers (0.75 to 3 UI). However, we considered that a dose above 2 U/μl of thrombin was too high to allow reperfusion after rt-PA treatment. Thus, 23 animals were excluded from the global analysis because 3 UI of thrombin was used. To allow stabilization of the clot, the pipette was removed 10 min after the injection of thrombin. Thrombolysis was initiated via the tail vein (200μL) of human recombinant tPA (rt-PA) (Boeringher Ingelheim - Alteplase®) (10% in bolus, 90% in perfusion over 40 min) at different doses (0.9, 5 and 10 mg/kg, i.v.) and at different times after stroke onset (from 20 min to 4 h). Control mice received saline under identical conditions. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37±0.5°C throughout the surgical procedure using a feedback-regulated heating system. Cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFv) was used as an index of the occlusion and was measured using either laser Doppler within the MCA territory or Doppler Speckle on the dorsal surface of the skull during 60 to 120 min.

Outcome assessment

The primary outcome was the lesion volume measured 24 h after stroke onset either by histological staining or MRI analysis. Brains were cryosectioned and slices (20 μm) were stained interchangeably using cresyl violet, thionine or hematoxylin/eosin. One section in 10 (10 or 20 μm thick) was stained and analyzed (covering the entire lesion). Regions of interest were determined through the use of a stereotaxic atlas for the mouse and an image analysis system (ImageJ software) was used to measure the infarct. MRI images were obtained from T2-weighted RARE sequences with either a 7T Bruker pharmascan MRI (TE/TR 51.3 ms/2500 ms) or a 9.4T Bruker biospec (TR/TE = 3300/60 ms). Lesion areas were quantified on T2-weighted images with ImageJ software (v1.45r, National Institutes of Health)

Statistical Analyses

Our primary analysis was to determine whether the efficacy of rt-PA differed according to the time-window of treatment and consisted of a pooled analysis of mean differences in infarct volume between rt-PA and saline (control), with stratification by treatment time-window (classified into <3 h and ≥3 h). For each experiment, we calculated the mean (±SD) difference in infarct volume between the rt-PA and the control group. The weighted mean difference was obtained using a random-effect meta-analysis; the weight given to each experiment being equal to the inverse of the variance of the difference. We then assessed whether the effect of rt-PA on infarct volumes differed between early and late rt-PA, using an interaction test. We also examined whether the result differed according to various experimental characteristics (e.g., the mouse strain (Swiss vs. C57Bl6), method of outcome assessment (MRI vs. histology), and dose of thrombin used — 0.75, 1 or 1.5 U/μL). This analysis was performed with RevMan 5.3 software. Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis after exclusion of data from the largest center (Caen).

Results

We collected data from 13 experimenters in 9 different laboratories, from 26 experimental studies carried out between 2007 and 2013 (Supplemental Table I). In total, data from 716 mice were available for study. As previously explained, we excluded 85 animals. Thus, 623 animals (291 saline-treated and 332 rt-PA-treated) were included in the final analysis (Supplemental Table I). In the rt-PA group, 235 animals had early rt-PA treatment (<3 h: from 20 to 40 min post-ictus) and 97 late treatment (≥3 h: 180 and 240 min post-ictus) (given i.v., 200μL whatever the dose used 0.9, 5 or 10 mg/kg). As such, data was evaluated in 19 early administration studies and 9 late rt-PA treatments.

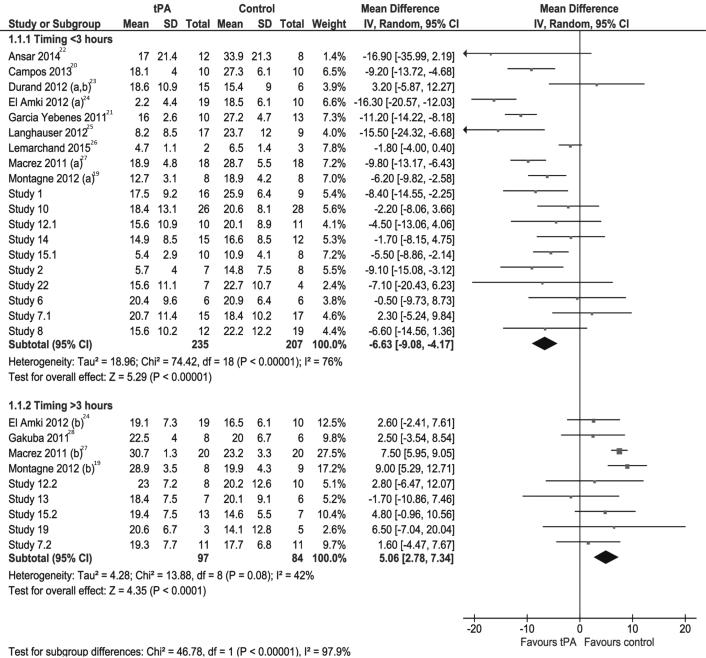

In the pooled analysis early rt-PA was associated with a significant reduction in the final infarct volume (absolute difference −6.63 mm3; 95% CI, −9.08 to −4.17; Psig<0.0001; I2 = 76%; figure 1)19–28 whereas late r-tPA treatment showed a deleterious effect (+5.06 mm3; 95% CI, +2.78 to +7.34; Psig<0.0001; I2 = 42%; figure 1), with a statistically significant qualitative interaction (Pint<0.00001).

Figure 1.

Pooled analysis of lesion volumes expressed in mm3, comparing the mean values of saline (control) and rt-PA treated animals (tPA). SD=standard deviation, TOTAL=number of animals per group, CI=confidence interval.

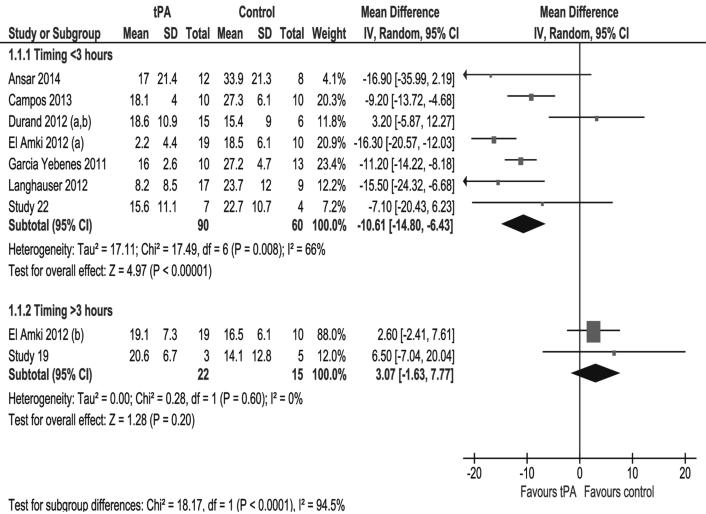

A similar beneficial effect was observed for the early rt-PA treatment when considering the seven studies performed outside the Caen laboratory: absolute difference = −10.61 mm3; 95% CI, −14.80 to −6.43; Psig = 0.008; I2 = 66% (figure 2)20–25. Looking at the two studies performed outside of our laboratory that applied late rt-PA treatment, there was still no beneficial effect (absolute difference +3.07 mm3; 95% CI, −1.63 to +7.77; Psig = 0.6; I2 = 0%; figure 2). Again, the interaction with the “time window” was still significant (Pint<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Pooled analysis of lesion volumes expressed in mm3, comparing the mean values of saline (control) and rt-PA treated animals (tPA) after exclusion of Caen data. SD=standard deviation, TOTAL=number of animals per group, CI=confidence interval.

Interaction at the subgroups level (table 1) — which includes mouse strain (Swiss mice vs. C57/Bl6 mice); method of evaluation to determine the lesion volume (i.e., histology vs. MRI analysis); whether studies were published or not, whether the studies were performed in a blinded manner or not; expertise of the experimenters; or whether the studies reporting hemorrhages are included or not, dose of rt-PA administered, — had no influence on the effects of rt-PA (figure 1).

Table 1.

Interaction between early and late rt-PA treatments in different subgroups.

| Number of studies | Mean Difference [95% CI] | I2 (%) | Test for Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse strains | ||||

| Swiss | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 14 | −6.31 [−9.03, −3.58] | 79 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 7 | 5.38 [2.93, 7.83] | 47 | |

| C57Bl | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 5 | −8.18 [−14.90, −1.46] | 64 | p<0.02 |

| Late rt-PA | 2 | 2.42 [−3.12, 7.96] | 0 | |

| Evaluation methods | ||||

| Histology | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 9 | −9.92 [−12.49, −7.35] | 52 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 2 | 5.65 [1.00, 10.31] | 70 | |

| MRI | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 10 | −3.76 [−6.28, −1.25] | 52 | p<0.0001 |

| Late rt-PA | 7 | 4.41 [1.41, 7.41] | 31 | |

| Published vs Unpublished studies | ||||

| Published | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 9 | −8.77 [−12.74, −4.80] | 87 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 10 | 6.26 [3.52, 9.00] | 55 | |

| Unpublished | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 2 | −4.70 [−6.78, −2.62] | 7 | p<0.0003 |

| Late rt-PA | 5 | 2.73 [−0.67, 6.14] | 0 | |

| Blind vs not blind studies | ||||

| Blind | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 17 | −6.35[−9.04, −3.66] | 78 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 8 | 4.19 [1.61, 6.78] | 26 | |

| Not blind | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 2 | −8.76[−13.05, −4.47] | 0 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 1 | 7.50[5.95, 9.05] | - | |

| Caen vs others | ||||

| Caen | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 12 | −4.89[−7.09, −2.69] | 57 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 7 | 5.31[2.76, 7.85] | 47 | |

| Others | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 7 | −10.61[−14.80, −6.43] | 66 | p<0.0001 |

| Late rt-PA | 2 | 3.07[−1.63, 7.77] | 0 | |

| Influence of training | ||||

| Upper 25% trained | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 7 | −6.45[9.37, −3.52] | 47 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 3 | 6.98[4.10, 9.86] | 53 | |

| Lower 25% trained | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 2 | −8.98[−13.26, −4.70] | 0 | - |

| Late rt-PA | 0 | - | - | |

| Doses of tPA | ||||

| High doses (5-10mg/kg) | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 18 | −5.98[−8.22, −3.74] | 68 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 8 | 5.48[3.12, 7.84] | 39 | |

| Low dose (0.9 mg/kg) | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 1 | −16.30[−20.57, −12.03] | - | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 1 | 2.60[−2.41, 7.61] | - | |

| Influence of reported hemorrhages | ||||

| Studies with no reported hemorrhages | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 17 | −5.50[−7.66, −3.34] | 59 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 8 | 5.48[3.12, 7.84] | 39 | |

| Studies with reported hemorrhages | ||||

| Early rt-PA | 2 | −13.52[−18.50, −8.54] | 73 | p<0.00001 |

| Late rt-PA | 1 | 2.60[−2.41, 7.61] | - |

Discussion

In this retrospective study of a large pooled analysis of multicenter preclinical data (based on a thromboembolic stroke model) we demonstrated that early (< 3 h) administration of rt-PA after cerebral ischemia is associated with a significant reduction in lesion volume, whereas late administration (≥ 3 h) has no, or a deleterious, effect.

Although pooled analyses of data are common in clinical studies, such analyses are rare in preclinical research and no pooled analysis exists on rt-PA in ischemic stroke in animals. Yet, such an approach is of major importance because most of therapeutic strategies with beneficial effects in experimental stroke models failed when evaluated in humans, or have not been translated into a clinical trial, due to lack of support from industry and/or clinicians. It is therefore crucial to provide drug companies and clinicians with reliable stroke models that represent the clinical situation as much as possible.

As the benefit of rt-PA is well established in humans, it appeared to us interesting to demonstrate that this benefit is also clear in an appropriate animal model of ischemic stroke. Usually, preclinical studies have small sample sizes and there is often a substantial heterogeneity in the stroke models used. Although we focused on a specific model of thromboembolic stroke and increased the sample size, we still observed a certain degree of heterogeneity across studies. This heterogeneity may be explained by variations in the animal strain, in the method of assessment, or in inter-individual technical aspects despite a well-standardized model. However, our sensitivity analyses were highly consistent with the main finding (i.e., a time-effect relationship between rt-PA administration and infarct volume).

The inclusion of a large sample population (623 animals), may have helped contribute to the validation of the model. Our group developed and characterized an embolic stroke model in mice, in which cerebral ishemia is induced by a local injection of thrombin directly into the middle cerebral artery. This leads to the immediate formation of a clot, cerebral blood flow disruption, and subsequent cortical infarction.12 Several other experimental stroke models exist and have been used for years in various animal species. However, those that use electrocoagulation, ligatures or a filament, are not appropriate in which to test thrombolytic drugs. Others researchers use the autologous injection of a clot, or microemboli, via the internal carotid artery to induce stroke, but such methods evince poor reproducibility and uniformity in the location of the lesion,29 and result in a high mortality rate.30,31 Accordingly, despite successful rt-PA-induced reperfusion, it is not surprising to observe opposite effects of rt-PA treatment on infarct size depending on the extent to which the models reflect the contribution of fibrinolysis, blood-brain barrier alterations, or neurotoxicity.

Reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analysis of preclinical stroke studies is increasing.14–18 In the present study, we evaluated the effects of rt-PA in a model of thromboembolic stroke with a large sample population and examined the effects of rt-PA dose, time of administration, animal strain, research centre and method for calculating the infarction volume in the mouse. Nonetheless, there are some potential limitations in our analysis. Inherent differences exist between animal and human studies and applying the same method of meta-analysis to preclinical data is not straightforward.16 Although we had the individual data available, we finally opted for a pooled analysis of group (Research center) studies. Indeed, in each study there is no heterogeneity in the animal, model which has the same characteristics at baseline, and consequently excludes adjustment for confounding factors. The main source of non-uniformity was the experiment (the study) itself. However, we also performed the same analyses with generalized linear models and found the same interaction with time (data not shown). In addition, although we initially used 10 mg/kg rt-PA, as is usually recommended in rodents, the current analysis shows that a dose as low as 0.9 mg/kg (the dose used in clinical studies), is sufficient to produce a beneficial effect with early rt-PA treatment.

Although, the original publication12 was based on data obtained from Swiss mice, the present data show similar results when using C57/BL6 animals. The use of different time windows, different doses and two strains of mice, together with histological analysis are in agreement with some of the recommendations made by the STAIR group.32 Furthermore, saline was used in all control groups instead of the vehicle containing L-arginine, which is used in clinical trials. Nevertheless, recent experimental studies demonstrated no significant effect of L-arginine compared to saline in a stoke model in rabbits.33,34 The outcome we used was infarct volume as functional recovery was not consistently assessed. Similarly, the influence of sex or co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, or age was not addressed. However, the main consequence of these factors is likely to increase heterogeneity and attenuate the effects rather than invalidate the findings.

In conclusion, we demonstrated in a pooled multicenter analysis that, in this experimental model of thromboembolic stroke, rt-PA treatment is beneficial when given early after stroke onset (< 3 h) and not beneficial when the administration is delayed (≥ 3h). On the global data, a power analysis revealed that for a single center trial, considering a power of 0.8 and an alpha risk of 0.05 (two-sided), a mean infarct volume of 20.9 mm3 in the control group and a standard deviation of ±10 mm3, 40 animals per group (drug-treated and a control group) would be required to detect a 30% reduction with early tPA. In contrast, a multi-center trial would require three times more animals, i.e., 123 animals per group (246 overall) if we assume the same heterogeneity across experiments that we observed in our meta-analysis (I2=76%).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by: Spanish grants PI12/00710 and RD12/0042/009; SAF2011-23354; RETICS RD12/0014/0003; Marie Curie Career Integration Grant (631246); European program ARISE (FP7); NIH grants (NS049263 and NS055104); grants from the INSERM (French National Institute for Health and Medical Research), the Foundation for Medical Research (FRM/N°DEQ20140329555), and the Regional Council of Lower Normandy.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Bruno A, Connors JJB, Demaerschalk BM, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Stem cells for the treatment of neurological disorders. Nature. 2006;441:1094–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher M. Acute ischemic stroke therapy: current status and future directions. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2013;11:1097–9. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2013.827450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Röther J, Ford GA, Thijs VNS. Thrombolytics in acute ischaemic stroke: historical perspective and future opportunities. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013;35:313–9. doi: 10.1159/000348705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howells DW, Sena ES, O'Collins V, Macleod MR. Improving the efficiency of the development of drugs for stroke. Int. J. Stroke. 2012;7:371–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Collins VE, Macleod MR, Donnan GA, Horky LL, van der Worp BH, Howells DW. 1,026 experimental treatments in acute stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:467–77. doi: 10.1002/ana.20741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hossmann K-A. The two pathophysiologies of focal brain ischemia: implications for translational stroke research. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1310–6. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endres M, Engelhardt B, Koistinaho J, Lindvall O, Meairs S, Mohr JP, et al. Improving outcome after stroke: overcoming the translational roadblock. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2008;25:268–78. doi: 10.1159/000118039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mergenthaler P, Meisel A. Do stroke models model stroke? Dis. Model. Mech. 2012;5:718–25. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirnagl U, Fisher M. International, multicenter randomized preclinical trials in translational stroke research: it's time to act. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:933–5. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karatas H, Erdener SE, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Gurer G, Soylemezoglu F, Dunn AK, et al. Thrombotic distal middle cerebral artery occlusion produced by topical FeCl(3) application: a novel model suitable for intravital microscopy and thrombolysis studies. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1452–60. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orset C, Macrez R, Young AR, Panthou D, Angles-Cano E, Maubert E, et al. Mouse model of in situ thromboembolic stroke and reperfusion. Stroke. 2007;38:2771–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.487520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Zhang RL, Jiang Q, Raman SB, Cantwell L, Chopp M. A new rat model of thrombotic focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:123–35. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199702000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ström JO, Ingberg E, Theodorsson A, Theodorsson E. Method parameters' impact on mortality and variability in rat stroke experiments: a meta-analysis. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moja L, Pecoraro V, Ciccolallo L, Dall'Olmo L, Virgili G, Garattini S. Flaws in animal studies exploring statins and impact on meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;44:597–612. doi: 10.1111/eci.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vesterinen HM, Sena ES, Egan KJ, Hirst TC, Churolov L, Currie GL, et al. Meta-analysis of data from animal studies: a practical guide. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2014;221:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsilidis KK, Panagiotou OA, Sena ES, Aretouli E, Evangelou E, Howells DW, et al. Evaluation of excess significance bias in animal studies of neurological diseases. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedder H, Vesterinen HM, Macleod MR, Wardlaw JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions tested in animal models of lacunar stroke. Stroke. 2014;45:563–70. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montagne A, Hébert M, Jullienne A, Lesept F, Le Béhot A, Louessard M, et al. Memantine improves safety of thrombolysis for stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:2774–81. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.669374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campos F, Qin T, Castillo J, Seo JH, Arai K, Lo EH, et al. Fingolimod reduces hemorrhagic transformation associated with delayed tissue plasminogen activator treatment in a mouse thromboembolic model. Stroke. 2013;44:505–11. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.679043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Yébenes I, Sobrado M, Zarruk JG, Castellanos M, Pérez de la Ossa N, Dávalos A, et al. A mouse model of hemorrhagic transformation by delayed tissue plasminogen activator administration after in situ thromboembolic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:196–203. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansar S, Chatzikonstantinou E, Wistuba-Schier A, Mirau-Weber S, Fatar M, Hennerici MG, et al. Characterization of a new model of thromboembolic stroke in C57 black/6J mice. Transl. Stroke Res. 2014;5:526–33. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0315-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durand A, Chauveau F, Cho T-H, Bolbos R, Langlois J-B, Hermitte L, et al. Spontaneous reperfusion after in situ thromboembolic stroke in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Amki M, Lerouet D, Coqueran B, Curis E, Orset C, Vivien D, et al. Experimental modeling of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator effects after ischemic stroke. Exp. Neurol. 2012;238:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langhauser FL, Heiler PM, Grudzenski S, Lemke A, Alonso A, Schad LR, et al. Thromboembolic stroke in C57BL/6 mice monitored by 9.4 T MRI using a 1H cryo probe. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2012;4:18. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemarchand E, Gauberti M, de Lizarrondo SM, Villain H, Repessé Y, Montagne A, et al. Impact of Alcohol Consumption on the Outcome of Ischemic Stroke and Thrombolysis: Role of the Hepatic Clearance of Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator. Stroke. 2015;46:1641–50. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macrez R, Obiang P, Gauberti M, Roussel B, Baron A, Parcq J, et al. Antibodies preventing the interaction of tissue-type plasminogen activator with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors reduce stroke damages and extend the therapeutic window of thrombolysis. Stroke. 2011;42:2315–22. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gakuba C, Gauberti M, Mazighi M, Defer G, Hanouz J-L, Vivien D. Preclinical evidence toward the use of ketamine for recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated thrombolysis under anesthesia or sedation. Stroke. 2011;42:2947–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.620468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang CX, Todd KG, Yang Y, Gordon T, Shuaib A. Patency of cerebral microvessels after focal embolic stroke in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:413–21. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romanos E, Planas AM, Amaro S, Chamorro A. Uric acid reduces brain damage and improves the benefits of rt-PA in a rat model of thromboembolic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:14–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carmichael ST. Rodent models of focal stroke: size, mechanism, and purpose. NeuroRx. 2005;2:396–409. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40:2244–50. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harston GWJ, Sutherland BA, Kennedy J, Buchan AM. The contribution of L-arginine to the neurotoxicity of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator following cerebral ischemia: a review of rtPA neurotoxicity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1804–16. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lapchak PA, Daley JT, Boitano PD. A blinded, randomized study of l-arginine in small clot embolized rabbits. Exp. Neurol. 2015;266C:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.