Abstract

The mammalian heart contains a population of resident macrophages that expands in response to myocardial infarction and hemodynamic stress. This expansion occurs likely through both local macrophage proliferation and monocyte recruitment. Given the role of macrophages in tissue remodeling, their contribution to adaptive processes in the heart is conceivable but currently poorly understood. In this review, we discuss monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity associated with cardiac stress, the cell’s potential contribution to the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis, and describe different tools to study and characterize these innate immune cells. Finally, we highlight their potential role as therapeutic targets.

Keywords: monocytes, macrophages, myocardial infarction, hemodynamic stress, fibrosis, cardiac remodeling

1. Introduction

The heart is composed of a heterogeneous population of cells including cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells. It is now clear that intercellular signaling and cross talk between cardiomyocytes and non-cardiomyocytes are critical in the initiation, propagation and development of cardiac remodeling. Left ventricular remodeling has originally been defined as changes in size, shape, structure and physiology of the ventricle [1]. Such remodeling processes follow different types of cardiac stress, like myocardial infarction (MI), myocarditis or chronic hypertension, and when uncontrolled can lead to heart failure or cardiac arrest resulting from pulseless electrical activity or arrhythmia. Therefore, great interest lies in the discovery of new therapeutic strategies, which can modulate adverse cardiac remodeling and prevent heart failure.

The discovery and evaluation of new therapeutic targets relies heavily on the use of small animal models. Indeed, rat and mouse heart failure models have been used over the past 40 years to explore the pathophysiology of heart failure and to develop novel therapies [2]. Permanent coronary ligation and transverse aortic constriction are perhaps the most widely used models for MI and pressure overload, respectively. Other models for hypertension-induced heart disease include genetic models, and exogenous administration of angiotensin II or mineralocorticoid (deoxycorticosterone acetate [DOCA] or aldosterone). DOCA-induced cardiac effects include cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in the absence of salt deprivation. These pathophysiological changes are accelerated by supra-normal salt intake and unilateral nephrectomy, and closely mimic the clinical condition of human heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [3,4]. Despite recent advantages in developing rodent heart failure models, translation of findings obtained in rodents is often not straight forward, as pathophysiological processes in humans are complex. Indeed, human heart failure frequently develops as a cluster of interrelated comorbidities rather than a single pathophysiological event. In the future, mammalian systems other than mouse may be needed to model complex neural, immune, endocrine and metabolic interactions during hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia, all contributing to human heart failure. On the other hand, lower costs, faster timelines and the availability of a great number of transgenic and knockout strains are important benefits of using mice to model heart failure. Moreover, the ability to assess cardiovascular physiology using multiple modalities, including echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging and micromanometer conductance catheters has removed a significant barrier to their use in heart failure research and makes the mouse a relevant model to retrieve significant mechanistic insights into human disease.

In this review, we summarize the current understanding of the contribution of immune cells, in particular monocytes and macrophages, to the pathogenesis of cardiac remodeling with a focus on the fibrotic response. We highlight the cross talk between these immune cells and parenchymal cells in the heart. Furthermore, we describe tools to study monocytes and macrophages in the heart and explore their potential role as therapeutic targets.

2. Monocytes and Macrophages

Monocytes and macrophages are part of the vertebrates’ innate immune system, and pursue distinct functions in the steady-state and during disease. It is now widely accepted that the innate immune system plays an important role both during the initial insult and the chronic phase of cardiac injury. In humans, three monocyte subsets have been identified based on the expression of CD14 and CD16: classical (CD14++CD16−), intermediate (CD14++CD16+) and nonclassical (CD14+CD16++) monocytes [5]. Heart failure in humans has also been associated with increased peripheral inflammation, monocytosis and distinct monocyte subset profiles [6–11]. On the other hand, mature murine monocytes have been classified into two subsets according to their expression of Ly-6C. Ly-6Chigh chemokine (C-C motif) receptor-2 (CCR2)high chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor-1 (CX3CR1)low monocytes preferentially accumulate in inflammatory sites, including acute MI, where they give rise to macrophages, and nonclassical Ly-6ClowCCR2lowCX3CR1high monocytes, which patrol the endothelium to maintain homeostasis [12]. Furthermore, the nonclassical Ly-6Clow monocytes in mouse blood are homologous to human nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes as shown by cell-depletion studies and transcriptional profiling [13,14]. The use of CD43 has been proposed to further subdivide murine Ly-6Chigh monocytes into classical Ly-6ChighCD43low and intermediate Ly-6ChighCD43high monocytes resembling the 3 subsets described for human monocytes [5]. Ly-6Chigh monocytes are produced in the bone marrow by hematopoietic progenitors that derive from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The most restricted monocyte progenitor is the common monocyte progenitor, which is developmentally downstream of monocyte-macrophage dendritic cell progenitors [15]. Ly-6Chigh monocytes produced in the bone marrow are released into the blood depending on CCR2 signaling, and travel to inflammatory sites where they participate in the host’s initial immune response [16]. Ly-6Clow monocytes arise from Ly-6Chigh monocytes through conversion, relying on a nuclear receptor subfamily-4-dependent transcriptional program [17]. HSCs can also intravasate into the blood and give rise to monocytes outside the bone marrow, which is called extracellular monocytopoeiesis [18,19]. This phenomenon is rare in the steady-state, but increases during inflammation. Furthermore, monocytes can also reside in the spleen, which functions as a reservoir for storage and rapid deployment of monocytes during inflammation [20]. The heart itself contains very few, if any, monocytes during steady-state conditions.

In contrast, macrophages are the primary immune cells that reside in the heart under physiological conditions. They appear as spindle-like cells and are found within the interstitial space or in close proximity of endothelial cells [21–23]. For the past half century, macrophages were thought to arise solely from circulating blood monocytes. However, recent studies using genetic fate mapping, parabiosis and adoptive transfer techniques show that tissue-resident macrophages in the brain, liver, lung, and skin do not derive from circulating monocytes but are replenished through local proliferation [24–27]. In contrast, intestinal or dermal macrophages, which have a high turnover rate, are constantly replaced by Ly-6Chigh blood monocytes [28,29]. In the steady-state heart, tissue-resident cardiac macrophages comprise discrete subsets, defined by their expression levels of histocompatibility-2 and CCR2 [30]. These macrophage subsets arise primarily from embryonic yolk-sac progenitors and self-maintain independent of bone marrow-derived monocytes through in situ proliferation. On the other hand, when the steady-state is perturbed during sterile injury or hemodynamic stress, the majority of cardiac macrophages are derived from blood monocytes [23,30]. Interestingly, a recent study by Molawi et al. claims declining self-renewal of embryo-derived cardiac macrophages with age, and their progressive substitution by monocyte-derived macrophages even in the absence of inflammation [31].

3. Monocytes and Macrophages in Cardiac Remodeling

3.1. Expansion of Macrophages

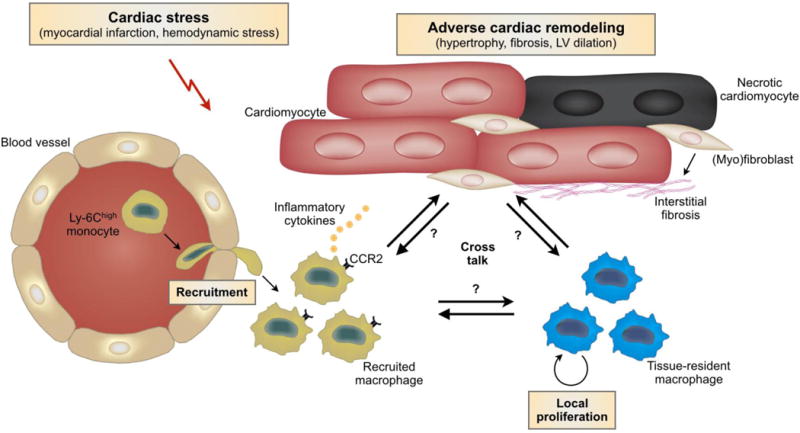

During various cardiac stresses, expansion of macrophage populations occurs through both local proliferation and monocyte recruitment (Fig. 1) [22,23,30,32]. Ly-6Chigh monocytes are the primary subset recruited to the heart [27,30,32–34]. In response to signals induced by ischemic cardiac injury, sequential recruitment of monocytes regulates the inflammatory and reparative response following MI [22]. During the early inflammatory phase of infarct healing, Ly-6Chigh monocytes infiltrate the infarcted myocardium in response to the marked upregulation of monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [35]. In a second phase, low numbers of Ly-6Clow monocytes are recruited via CX3CR1 [22]. Secondary to angiotensin II-induced hemodynamic stress, monocyte-derived CCR2+ macrophages require monocyte input prior to proliferative expansion in the tissue [30]. The CCR2+ macrophage subset is thought to be involved mainly in promoting and regulating inflammation; however, the intensity of the chronic inflammatory reaction is orders of magnitude lower after pressure overload and hypertensive cardiac stress than what is observed after acute ischemic injury [36,37]. This discrepancy is probably related to the difference in local insult stimulus, which is drastic in the setting of MI. Indeed, ischemic injury results in acutely dying myocytes leading to rapid accumulation of inflammatory cells [38]. The basis for initiation of the inflammatory reaction in pressure overloaded myocardium remains poorly understood and may involve activation of innate immune signals due to cardiomyocyte death, reactive oxygen generation, or angiotensin-mediated pro-inflammatory actions [39]. CCR2+ macrophages are capable of producing and secreting large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including those associated with the NLPR3 inflammasome, which is required to process and deliver interleukin (IL)-1β to the heart during cardiac stress [30]. Indeed, angiotensin II–induced inflammasome activation and IL-1β production are blocked in mice with CCR2 deficiency [40–42]. Furthermore, CCR2 knockout in bone marrow cells or inhibition of MCP-1 with neutralizing antibodies markedly reduces vascular inflammation and myocardial fibrosis without affecting hypertrophy during angiotensin II infusion and pressure overload [43,44]. Blocking this chemotactic pathway appears to have a pronounced impact on fibrotic remodeling and might have a more direct role in regulating fibroblast function. Also, inhibition of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 with neutralizing antibodies reduces infiltrating monocytes and suppresses cardiac fibrosis during pressure overload [45]. In conclusion, monocyte recruitment, followed by differentiation to macrophages and macrophage proliferation, contribute to the expansion of cardiac macrophages following ischemic and hemodynamic stress.

Fig. 1. Expansion of macrophages during cardiac stress.

After cardiac stress such as myocardial infarction or hemodynamic stress, there is a marked expansion of the cardiac macrophage population through both local proliferation and monocyte recruitment. CCR2+ macrophages are capable of producing and secreting large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which contribute to adverse cardiac remodeling. However, our current knowledge regarding the cross talk between macrophage subpopulations and parenchymal cells in the heart is still limited and requires further exploration. Abbreviation: LV, left ventricular.

3.2. Macrophage Subpopulations

Functional binary categorization of macrophages, such as the M1/M2 classification, is used as an easy, but probably too simplistic way to address the macrophage heterogeneity associated with cardiac stress. We propose using the terms inflammatory/reparative macrophages instead, as we frequently observed that the typical M1/M2 markers used in in vitro studies are not necessarily helpful to describe macrophage phenotypes in vivo. During cardiac injury, the resolution of neutrophil recruitment by phagocytic macrophages is critical for limiting tissue injury and promoting the transition to tissue healing. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells are believed to initiate this process by decreasing their production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), and increasing their production of anti-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) [46,47]. Indeed, macrophage depletion during the early inflammatory phase after MI results in increased necrotic debris and neutrophil presence [22,30,48]. The transition from inflammatory to reparative macrophages occurs after ischemia, resembling in vitro polarization from the so-called “M1” to “M2” macrophage phenotype. However, the concept of M1/M2 macrophage polarization is derived from in vitro studies and do not reflect the more subtle phenotypes observed in vivo. Indeed, macrophages do not form stable subsets but respond to a combination of factors present in the tissue resulting in complex, even mixed, phenotypes. Recent technological and analytical advances in epigenetic, gene expression, and functional studies revealed a spectrum of macrophage activation states extending the current M1 versus M2-polarization model [49]. This resource can serve as a framework for future research into regulation of macrophage activation in health and disease.

Regulators of macrophage polarization such as interferon regulatory factor-5 (IRF5) and myeloid mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) have been shown to be involved in cardiac remodeling. In vivo silencing of IRF5 reduces inflammatory macrophages and improves infarct healing [50]. MR activation by mineralocorticoids (e.g. aldosterone) enhances the polarization to inflammatory macrophages, whereas MR deficiency in macrophages mimics the effects of MR antagonists and protects against cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [51]. In contrast, scavenger receptor class-A on cardiac macrophages, which is a key modulator of inflammation, exerts a protective effect against MI by contributing to the reparative macrophage phenotype, and anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic remodeling [52]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is also a critical regulator of macrophage polarization during cardiac remodeling. Myeloid-specific deletion of prolyl hydroxylase domain protein-2, an enzyme that induces degradation of HIF, attenuates macrophage recruitment, inflammatory gene expression, and cardiac remodeling upon infusion of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester/angiotensin II [53]. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-1 induces cardiac fibrosis after angiotensin II infusion at least in part through signal transducer and activator of transcription-3-dependent macrophage proliferation and activation [54]. In contrast, IL-12 produced by cardiac macrophages activates interferon-γ-producing CD4+ T cells, which shifts macrophages towards the inflammatory phenotype and subsequently prevents excessive angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis [55]. microRNAs (miRs) have also been shown to regulate the myeloid cell phenotype and modulate cardiac remodeling (for in-depth review see also [56]). Knockout of miR-155 for example reduces angiotensin II– and pressure overload–induced polarization to inflammatory macrophages, hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction [57].

These data suggest that the transition of macrophage phenotypes from inflammatory to reparative could be a potential mechanism of cardioprotection after MI, but prolonged activation of reparative macrophages may eventually contribute to extensive cardiac fibrosis, increased stiffness and diastolic dysfunction. Indeed, a recent study by Kanellakis et al. shows that inhibition of IL-4, a potent inducer of reparative macrophages, with neutralizing antibodies attenuates cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy during pressure overload, suggesting that IL-4 is pro-fibrotic and may exacerbate adverse cardiac remodeling [58].

3.3. Macrophages as Fibrogenic Mediators

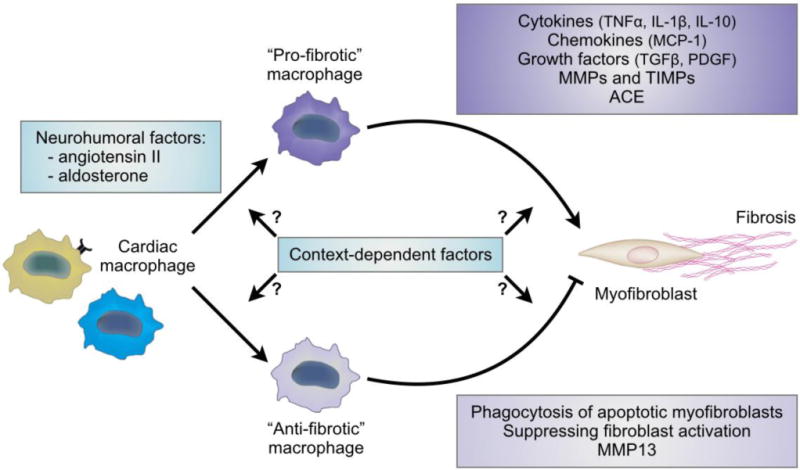

The activation of cardiac fibroblasts, transdifferentiation into secretory and contractile cells, termed myofibroblasts, and subsequent extracellular matrix deposition are key cellular events that drive the fibrotic response during cardiac stress (for in-depth review see also [59–61]). Macrophages are almost always found in close proximity with collagen-producing myofibroblasts [62,63]. Due to their functional and phenotypic plasticity, the role of monocytes and macrophages in mediating the fibrotic response is complex and context-dependent (Fig. 2). Macrophages exert a wide range of actions that alter the extracellular matrix: through their phagocytic properties, by producing cytokines, chemokines and growth factors including TGFβ and platelet-derived growth factor, by disrupting normal cardiac structures, and by altering the extracellular matrix turnover through regulating the balance of various matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs [44,64–66]. In addition, the activation of cardiac fibroblasts, non-adaptive fibrosis and subsequently increased myocardial stiffness after angiotensin II infusion requires the induction of MCP-1, which suggests the causal contribution of monocytes to the fibrotic response [67]. Interestingly, cardiac senescence is associated with phenotypic changes in resident macrophages including upregulation of pro-fibrotic genes, which possibly contribute to aging-associated cardiac fibrosis [68]. Westermann et al. also showed that TGFβ-producing inflammatory cells contribute to diastolic dysfunction in human heart failure with preserved ejection fraction by triggering the accumulation of extracellular matrix [69]. Most studies on the role of monocytes and macrophages in cardiac fibrosis have focused on their pro-fibrotic actions; however, they could also mediate resolution of fibrosis by removing apoptotic myofibroblasts, by expressing high levels of MMP13 and by suppressing fibroblast activation as has been shown in the setting of hepatic fibrosis [66,70,71].

Fig. 2. Cardiac macrophages as regulators of the fibrotic response after cardiac stress.

Macrophages are found in close proximity with collagen-producing myofibroblasts and contribute to the fibrotic response after cardiac stress. Neurohumoral factors such as angiotensin II and aldosterone drive macrophages towards a fibrogenic phenotype. Macrophages also exert a wide range of anti-fibrotic actions in addition to their pro-fibrotic effects, but the context-depending factors driving macrophages towards a pro-fibrotic or an anti-fibrotic phenotype are yet-to-be determined. Abbreviation: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases, PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TIMPs, tissue inhibitors of MMPs; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Monocytes and macrophages also contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis by interacting with neurohumoral factors such as angiotensin II and aldosterone. Indeed, macrophages in the injured heart are a source of renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme, which are necessary for the local production of angiotensin II and subsequent activation of cardiac fibroblasts [72]. Angiotensin II also regulates the mobilization of monocytes, i.e. macrophage progenitors, in the spleen [73]. In addition, aldosterone directly influences the cardiac fibrotic response by driving macrophages towards a fibrogenic phenotype [51,74].

Despite recent discoveries describing a causal role of monocytes and macrophages in the fibrotic response after cardiac stress, dissecting the context-depending factors driving macrophages towards a pro-fibrotic or an anti-fibrotic phenotype is an ongoing process, and many cell-cell interactions still remain to be determined (Fig. 2).

4. Tools to Study Monocytes and Macrophages

Monocytes and tissue macrophages are typically studied at cellular resolution by staining for cell surface markers in histology or multicolor flow cytometry. These markers include CD11b, CD45, CD68, CD115, F4/80, Ly-6C and MAC-3 in addition to the core macrophage signature suggested by the Immunological Genome Project, which include FCGR1 and MerTK [75]. The development of transgenic mice such as the Cx3cr1GFP/+ reporter mouse also facilitated the detection of cardiac macrophages and improved the sensitivity of ex vivo histology for detecting macrophages and their dendrite-like protrusions in the myocardial tissue context [21,23]. Additionally, recently developed real-time in vivo imaging techniques make it possible to track migration patterns of monocytes in the heart with microscopic resolution [76,77]. Monocytes and macrophages can also be probed with nanoparticles [78] to follow them or determine their specific function at the organ level by noninvasive imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging [79], positron emission tomography [80], fluorescence molecular tomography [81], or hybrid approaches [82].

Furthermore, monocytes and macrophages can be functionally characterized using specific depletion methods such as clodronate liposomes. Clodronate is a small hydrophilic molecule that binds intracellular ATP and inhibits ATP function resulting in cellular apoptosis. Monocytes and, with less efficiency macrophages, can be targeted by encapsulation of clodronate into liposomes. Organ restriction of depletion can be attempted by choosing the appropriate administration route [83]. Depletion of myeloid cells can also be accomplished by using Cd11bDTR transgenic mice. These transgenic mice have a diphtheria toxin inducible system under control of the human CD11b promoter that transiently depletes myeloid cells in various tissues [84].

To study and assess the contribution of monocytes to the turnover of cardiac macrophages in the steady-state and during disease, one could use the parabiosis setup, in addition to fate mapping, and adoptive transfer approaches. Parabiosis surgery joins the circulation of two mice, whose circulating blood cells then mix. This setup enables the quantification of recruited macrophages by determining the percentage of macrophages that derived from circulating monocytes made in the donor mouse [23]. Although parabiosis provides a convenient tool to study the recruitment of cells, it may also induce artifacts through pro-inflammatory stimuli. Adoptive transfer of bone marrow HSCs into an irradiated recipient mouse can be used to assess the contribution of recruitment to the macrophage population. A disadvantage of this approach is that radiation may deplete the cardiac resident macrophages, or some relevant fraction thereof. In addition, several inducible fate mapping models including the Runx1MercreMer, Csf1rMercreMer, Cx3cr1creER, and KitMercreMer mice are currently available and are a convenient tool to study the ontogenesis of tissue-resident cardiac macrophages in the steady-state and during disease [24,26,85–87].

5. Clinical Translation and Conclusions

The growing body of evidence implicating immune cells in the initiation and propagation of cardiac remodeling lends itself to exploiting this knowledge to explore new therapeutic avenues. Indeed, monocytes and macrophages appear to coordinate cardiomyocyte and non-cardiomyocyte responses during maladaptive remodeling after cardiac stress. Because of their functional and phenotypic versatility, regulating specific macrophage phenotypes rather than depleting them may spare important immune functions, such as repair and defense against infection, while preventing specific deleterious effects contributing to adverse cardiac remodeling.

A valid strategy could be to tackle the inappropriate activation of pro-inflammatory CCR2+ cardiac macrophages in the setting of sterile inflammation or to prevent the infiltration of Ly-6Chigh monocytes during hypertension-induced cardiac fibrosis [22,44,88,89]. These data suggest that recruited Ly-6Chigh monocytes have a pathological role, in contrast to tissue-resident cardiac macrophages, in the setting of cardiac injury. Furthermore, it is possible to phenotypically change inflammatory macrophages by nanoparticle-delivered small interfering RNA. The ease of delivering nanomaterials to phagocytic immune cells renders macrophages a prime target for in vivo RNAi [90]. Advantages of applying RNAi to target immune reactions include the selectivity for specific gene products (thereby avoiding unwanted side effects of broad immunosuppression) and the ability to reach intracellular decision nodes such as transcription factors involved in macrophage polarization [50]. Inflammatory cardiac macrophages during ischemic injury can also be modulated to a reparative state by phosphatidylserine-presenting liposomes, mimicking the anti-inflammatory effects of apoptotic cells [91]. A recent study by de Couto et al. showed that cardiac macrophages can be polarized toward a distinctive cardioprotective phenotype in the ischemic heart by administering cardiosphere-derived cells, which are a stem-like population that is derived ex vivo from cardiac biopsies [92]. Together, these studies suggest that manipulation of macrophage phenotypes could be exploited therapeutically to improve outcome after sterile injury. Unfortunately, our current knowledge regarding molecular pathways involved in driving macrophages toward specific phenotypic profiles is still limited and requires further exploration. In addition, it is quite reasonable to assume that cardiac macrophages also pursue salient functions that promote myocardial health, thus indiscriminate targeting strategies could be harmful. Novel, non-biased methods combining experimental data with mathematical modeling may shed light on the complex, spatiotemporal plasticity of cardiac macrophages after cardiac stress [49,93,94]. Finally, most of our current understanding of macrophage phenotype and function is derived from mouse models and still requires clinical translation and validation in human tissue samples.

Highlights.

-

-

Macrophages are an intrinsic part of the heart under physiological conditions

-

-

Cardiac macrophages expand in response to stress

-

-

Macrophage expansion through monocyte recruitment associates with cardiac remodeling

-

-

Monocytes and macrophages may exert a wide range of pro- and anti-fibrotic actions

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institutes of Health R01HL114477, R01HL117829, and R01HL096576. Maarten Hulsmans was funded by the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- CCR2

chemokine (C-C motif) receptor-2

- CX3CR1

chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor-1

- DOCA

deoxycorticosterone acetate

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HSCs

hematopoietic stem cells

- IL

interleukin

- IRF5

interferon regulatory factor-5

- MCP-1

monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1

- MI

myocardial infarction

- miR

microRNA

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor-β

- TIMPs

tissue inhibitors of MMPs

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation. 1990;81:1161–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patten RD, Hall-Porter MR. Small animal models of heart failure: development of novel therapies, past and present. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:138–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.839761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brilla CG, Weber KT. Mineralocorticoid excess, dietary sodium, and myocardial fibrosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka K, Wilson RM, Essick EE, Duffen JL, Scherer PE, Ouchi N, et al. Effects of adiponectin on calcium-handling proteins in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:976–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maekawa Y, Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, Asakura Y, Takahashi T, Ishikawa S, et al. Prognostic significance of peripheral monocytosis after reperfused acute myocardial infarction:a possible role for left ventricular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:241–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barisione C, Garibaldi S, Ghigliotti G, Fabbi P, Altieri P, Casale MC, et al. CD14CD16 monocyte subset levels in heart failure patients. Dis Markers. 2010;28:115–24. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wrigley BJ, Lip GY, Shantsila E. The role of monocytes and inflammation in the pathophysiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1161–71. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrigley BJ, Shantsila E, Tapp LD, Lip GY. Increased expression of cell adhesion molecule receptors on monocyte subsets in ischaemic heart failure. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:92–100. doi: 10.1160/TH13-02-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shantsila E, Tapp LD, Wrigley BJ, Pamukcu B, Apostolakis S, Montoro-García S, et al. Monocyte subsets in coronary artery disease and their associations with markers of inflammation and fibrinolysis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;234:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glezeva N, Voon V, Watson C, Horgan S, McDonald K, Ledwidge M, et al. Exaggerated inflammation and monocytosis associate with diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: evidence of M2 macrophage activation in disease pathogenesis. J Card Fail. 2015;21:167–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunderkötter C, Nikolic T, Dillon MJ, Van Rooijen N, Stehling M, Drevets DA, et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172:4410–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingersoll MA, Spanbroek R, Lottaz C, Gautier EL, Frankenberger M, Hoffmann R, et al. Comparison of gene expression profiles between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Blood. 2010;115:e10–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hettinger J, Richards DM, Hansson J, Barra MM, Joschko AC, Krijgsveld J, et al. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:821–30. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serbina NV, Pamer EG. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:311–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna RN, Carlin LM, Hubbeling HG, Nackiewicz D, Green AM, Punt JA, et al. The transcription factor NR4A1 (Nur77) controls bone marrow differentiation and the survival of Ly6C-monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:778–85. doi: 10.1038/ni.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbins CS, Chudnovskiy A, Rauch PJ, Figueiredo JL, Iwamoto Y, Gorbatov R, et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis generates Ly-6C(high) monocytes that infiltrate atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2012;125:364–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.061986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leuschner F, Rauch PJ, Ueno T, Gorbatov R, Marinelli B, Lee WW, et al. Rapid monocyte kinetics in acute myocardial infarction are sustained by extramedullary monocytopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:123–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto AR, Paolicelli R, Salimova E, Gospocic J, Slonimsky E, Bilbao-Cortes D, et al. An abundant tissue macrophage population in the adult murine heart with a distinct alternatively-activated macrophage profile. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heidt T, Courties G, Dutta P, Sager HB, Sebas M, Iwamoto Y, et al. Differential contribution of monocytes to heart macrophages in steady-state and after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2014;115:284–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamoutounour S, Guilliams M, Montanana Sanchis F, Liu H, Terhorst D, Malosse C, et al. Origins and functional specialization of macrophages and of conventional and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in mouse skin. Immunity. 2013;39:925–38. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Beaudin AE, Sojka DK, Carrero JA, Calderon B, et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molawi K, Wolf Y, Kandalla PK, Favret J, Hagemeyer N, Frenzel K, et al. Progressive replacement of embryo-derived cardiac macrophages with age. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2151–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilgendorf I, Gerhardt LM, Tan TC, Winter C, Holderried TA, Chousterman BG, et al. Ly-6Chigh monocytes depend on Nr4a1 to balance both inflammatory and reparative phases in the infarcted myocardium. Circ Res. 2014;114:1611–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jakubzick C, Gautier EL, Gibbings SL, Sojka DK, Schlitzer A, Johnson TE, et al. Minimal differentiation of classical monocytes as they survey steady-state tissues and transport antigen to lymph nodes. Immunity. 2013;39:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frangogiannis NG, Dewald O, Xia Y, Ren G, Haudek S, Leucker T, et al. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CC chemokine ligand 2 in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2007;115:584–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, Koerting A, Ren G, Abou-Khamis T, et al. CCL2/Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ Res. 2005;96:881–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163017.13772.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia Y, Lee K, Li N, Corbett D, Mendoza L, Frangogiannis NG. Characterization of the inflammatory and fibrotic response in a mouse model of cardiac pressure overload. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131:471–81. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicoletti A, Heudes D, Mandet C, Hinglais N, Bariety J, Michel JB. Inflammatory cells and myocardial fibrosis: spatial and temporal distribution in renovascular hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:1096–107. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1230719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:549–74. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mezzaroma E, Toldo S, Farkas D, Seropian IM, Van Tassell BW, Salloum FN, et al. The inflammasome promotes adverse cardiac remodeling following acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19725–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bracey NA, Gershkovich B, Chun J, Vilaysane A, Meijndert HC, Wright JR, et al. Mitochondrial NLRP3 protein induces reactive oxygen species to promote Smad protein signaling and fibrosis independent from the inflammasome. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:19571–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.550624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bracey NA, Beck PL, Muruve DA, Hirota SA, Guo J, Jabagi H, et al. The Nlrp3 inflammasome promotes myocardial dysfunction in structural cardiomyopathy through interleukin-1β. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:462–72. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.068338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishibashi M, Hiasa K, Zhao Q, Inoue S, Ohtani K, Kitamoto S, et al. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 on monocytes in hypertension-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Circ Res. 2004;94:1203–10. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126924.23467.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Takeya M, Takeshita A, Egashira K, et al. Hypertensive myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction: another model of inflammation. Hypertension. 2004;43:739–45. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118584.33350.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Niiyama H, Tahara N, Kusaba K, et al. Roles of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in hypertensive cardiac remodeling. Hypertension. 2003;41:819–23. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000056108.73219.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voll RE, Herrmann M, Roth EA, Stach C, Kalden JR, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–1. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wan E, Yeap XY, Dehn S, Terry R, Novak M, Zhang S, et al. Enhanced efferocytosis of apoptotic cardiomyocytes through myeloid-epithelial-reproductive tyrosine kinase links acute inflammation resolution to cardiac repair after infarction. Circ Res. 2013;113:1004–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue J, Schmidt SV, Sander J, Draffehn A, Krebs W, Quester I, et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity. 2014;40:274–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Courties G, Heidt T, Sebas M, Iwamoto Y, Jeon D, Truelove J, et al. In vivo silencing of the transcription factor IRF5 reprograms the macrophage phenotype and improves infarct healing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1556–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Usher MG, Duan SZ, Ivaschenko CY, Frieler RA, Berger S, Schütz G, et al. Myeloid mineralocorticoid receptor controls macrophage polarization and cardiovascular hypertrophy and remodeling in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3350–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI41080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Y, Zhang H, Lu Y, Bai H, Xu Y, Zhu X, et al. Class A scavenger receptor attenuates myocardial infarction-induced cardiomyocyte necrosis through suppressing M1 macrophage subset polarization. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:1311–28. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikeda J, Ichiki T, Matsuura H, Inoue E, Kishimoto J, Watanabe A, et al. Deletion of phd2 in myeloid lineage attenuates hypertensive cardiovascular remodeling. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000178. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang M, Zheng J, Miao Y, Wang Y, Cui W, Guo J, et al. Serum-glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 regulates alternatively activated macrophage polarization contributing to angiotensin II-induced inflammation and cardiac fibrosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1675–86. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Zhang C, Wu Y, Han Y, Cui W, Jia L, et al. Interleukin-12p35 deletion promotes CD4 T-cell-dependent macrophage differentiation and enhances angiotensin II-Induced cardiac fibrosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1662–74. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.249706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thum T. miRNA modulation of cardiac fibroblast phenotype. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.023. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heymans S, Corsten MF, Verhesen W, Carai P, van Leeuwen RE, Custers K, et al. Macrophage microRNA-155 promotes cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circulation. 2013;128:1420–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanellakis P, Ditiatkovski M, Kostolias G, Bobik A. A pro-fibrotic role for interleukin-4 in cardiac pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:77–85. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Small E, Lighthouse JK. Transcriptional control of cardiac fibroblast plasticity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.016. in press, JMCC9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hermans KC, Daskalopoulos EP, Blankesteijn WM. The Janus face of myofibroblasts in the remodeling heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.017. in press, JMCC9597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papageorgiou AP, Rienks M. Novel regulators of cardiac inflammation: matricellular proteins expand their repertoire. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.01.008. in press, JMCC9609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frangogiannis NG, Mendoza LH, Ren G, Akrivakis S, Jackson PL, Michael LH, et al. MCSF expression is induced in healing myocardial infarcts and may regulate monocyte and endothelial cell phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H483–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frangogiannis NG, Shimoni S, Chang SM, Ren G, Shan K, Aggeli C, et al. Evidence for an active inflammatory process in the hibernating human myocardium. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1425–33. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62568-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ren J, Yang M, Qi G, Zheng J, Jia L, Cheng J, et al. Proinflammatory protein CARD9 is essential for infiltration of monocytic fibroblast precursors and cardiac fibrosis caused by Angiotensin II infusion. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:701–7. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kagitani S, Ueno H, Hirade S, Takahashi T, Takata M, Inoue H. Tranilast attenuates myocardial fibrosis in association with suppression of monocyte/macrophage infiltration in DOCA/salt hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1007–15. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wynn TA, Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:245–57. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haudek SB, Cheng J, Du J, Wang Y, Hermosillo-Rodriguez J, Trial J, et al. Monocytic fibroblast precursors mediate fibrosis in angiotensin-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pinto AR, Godwin JW, Chandran A, Hersey L, Ilinykh A, Debuque R, et al. Age-related changes in tissue macrophages precede cardiac functional impairment. Aging (Albany NY) 2014;6:399–413. doi: 10.18632/aging.100669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Westermann D, Lindner D, Kasner M, Zietsch C, Savvatis K, Escher F, et al. Cardiac inflammation contributes to changes in the extracellular matrix in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:44–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.931451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fallowfield JA, Mizuno M, Kendall TJ, Constandinou CM, Benyon RC, Duffield JS, et al. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol. 2007;178:5288–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2012;110:159–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weber KT, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC. Myofibroblast-mediated mechanisms of pathological remodelling of the heart. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:15–26. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, Ryan R, Pucci F, Sio SW, et al. Angiotensin II drives the production of tumor-promoting macrophages. Immunity. 2013;38:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rickard AJ, Morgan J, Tesch G, Funder JW, Fuller PJ, Young MJ. Deletion of mineralocorticoid receptors from macrophages protects against deoxycorticosterone/salt-induced cardiac fibrosis and increased blood pressure. Hypertension. 2009;54:537–43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1118–28. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee S, Vinegoni C, Feruglio PF, Fexon L, Gorbatov R, Pivoravov M, et al. Real-time in vivo imaging of the beating mouse heart at microscopic resolution. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1054. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jung K, Kim P, Leuschner F, Gorbatov R, Kim JK, Ueno T, et al. Endoscopic time-lapse imaging of immune cells in infarcted mouse hearts. Circ Res. 2013;112:891–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ. Imaging macrophages with nanoparticles. Nat Mater. 2014;13:125–38. doi: 10.1038/nmat3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sosnovik DE, Nahrendorf M, Deliolanis N, Novikov M, Aikawa E, Josephson L, et al. Fluorescence tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of myocardial macrophage infiltration in infarcted myocardium in vivo. Circulation. 2007;115:1384–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.663351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee WW, Marinelli B, van der Laan AM, Sena BF, Gorbatov R, Leuschner F, et al. PET/MRI of inflammation in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik DE, Waterman P, Swirski FK, Pande AN, Aikawa E, et al. Dual channel optical tomographic imaging of leukocyte recruitment and protease activity in the healing myocardial infarct. Circ Res. 2007;100:1218–25. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265064.46075.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Majmudar MD, Keliher EJ, Heidt T, Leuschner F, Truelove J, Sena BF, et al. Monocyte-directed RNAi targeting CCR2 improves infarct healing in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Circulation. 2013;127:2038–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Rooijen N, Hendrikx E. Liposomes for specific depletion of macrophages from organs and tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;605:189–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-360-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kierdorf K, Erny D, Goldmann T, Sander V, Schulz C, Perdiguero EG, et al. Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1- and Irf8-dependent pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:273–80. doi: 10.1038/nn.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518:547–51. doi: 10.1038/nature13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sheng J, Ruedl C, Karjalainen K. Most Tissue-Resident Macrophages Except Microglia Are Derived from Fetal Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Immunity. 2015;43:382–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dunay IR, Damatta RA, Fux B, Presti R, Greco S, Colonna M, et al. Gr1(+) inflammatory monocytes are required for mucosal resistance to the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2008;29:306–17. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim YG, Kamada N, Shaw MH, Warner N, Chen GY, Franchi L, et al. The Nod2 sensor promotes intestinal pathogen eradication via the chemokine CCL2-dependent recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Immunity. 2011;34:769–80. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mulder WJ, Jaffer FA, Fayad ZA, Nahrendorf M. Imaging and nanomedicine in inflammatory atherosclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:239sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harel-Adar T, Ben Mordechai T, Amsalem Y, Feinberg MS, Leor J, Cohen S. Modulation of cardiac macrophages by phosphatidylserine-presenting liposomes improves infarct repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1827–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015623108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de Couto G, Liu W, Tseliou E, Sun B, Makkar N, Kanazawa H, et al. Macrophages mediate cardioprotective cellular postconditioning in acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3147–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI81321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang Y, Yang T, Ma Y, Halade GV, Zhang J, Lindsey ML, et al. Mathematical modeling and stability analysis of macrophage activation in left ventricular remodeling post-myocardial infarction. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(Suppl 6):S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S6-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jin YF, Han HC, Berger J, Dai Q, Lindsey ML. Combining experimental and mathematical modeling to reveal mechanisms of macrophage-dependent left ventricular remodeling. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]