Abstract

Background

Expanded efforts to detect and treat depression among college students, a peak period of onset, have the potential to bear high human capital value from a societal perspective because depression increases college withdrawal rates. However, it is not clear whether evidence-based depression therapies are as effective in college students as in other adult populations. The higher levels of cognitive functioning and IQ and higher proportions of first-onset cases might lead to treatment effects being different among college students relative to the larger adult population.

Methods

We conducted a metaanalysis of randomized trials comparing psychological treatments of depressed college students relative to control groups and compared effect sizes in these studies to those in trials carried out in unselected populations of depressed adults.

Results

The 15 trials on college students satisfying study inclusion criteria included 997 participants. The pooled effect size of therapy versus control was g = 0.89 (95% CI: 0.66~1.11; NNT = 2.13) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57; 95% CI: 23~72). None of these trials had low risk of bias. Effect sizes were significantly larger when students were not remunerated (e.g. money, credit), received individual versus group therapy, and were in trials that included a waiting list control group. No significant difference emerged in comparing effect sizes among college students versus adults either in simple mean comparisons or in multivariate metaregression analyses.

Conclusions

This metaanalysis of trials examining psychological treatments of depression in college students suggests that these therapies are effective and have effect sizes comparable to trials carried out among depressed adults.

Keywords: depression, college students, psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, behavioral activation therapy, metaanalysis

INTRODUCTION

The college years are a peak age period for depression onset—particularly for the occurrence of first episodes.[1,2] In high-income countries, more than half of young adults are enrolled in higher education.[3,4] Therefore universities have the potential to become a key setting for the prevention and treatment of depression (as well as for a number of other mental disorders). Mental disorders often result in a cascade of negative educational, economic, and social outcomes,[5–7] including elevated risk of withdrawal from college prior to completion,[8,9] suggesting that detection and effective treatment of these disorders early in the college career might bear important positive human capital effects from a societal perspective, as well as from the perspective of the patient.

But a question can be raised about the effectiveness of standard evidence-based depression treatments among college students. It is possible that these treatments are more effective in college students, because there are some indications that therapies are more effective in people with good cognitive functioning[10] and people with a higher IQ.[11] Depressive disorders in college students also differ from those in the general population in that these are probably more often first-onset disorders, while in adults in older age groups recurrent depressive disorders are more common. Although this has not been examined as a predictor of outcome it may be possible that first-onset depressive disorders can be treated better and that the effects of treatments in student populations are therefore higher in college students.

On the other hand, it could also be assumed that therapies are less effective in depressed college students, because in older age groups bipolar disorders will probably be excluded more effectively, while college students with a bipolar diathesis will in many cases start out with a depressive episode before they have their first manic or hypomanic episode. This might lead to worse treatment response in a sample of depressed college students than in a sample of depressed adults. Of note, there are also other factors that may account for treatment response differences including patterns of substance use and irregular sleep schedules.

Choosing among these competing possibilities requires comparative analysis of treatment effectiveness in samples of college students versus more general adult samples. Although a number of trials of psychological treatments for depression among college students have been carried out in the past decades, no metaanalysis has integrated the results of these trials. Several metaanalyses examined the effects of interventions among college students on general distress,[12] preventive, and early intervention,[3] and technology-based interventions.[13] However, no metaanalysis has tested the effects of psychological interventions of depression in college students.

At the same time, a relatively large number of trials have focused on psychological treatment for depression in college students. This is true in part because many clinical researchers have easy access to college students as convenience samples to test new treatments or experimental interventions. Many of these studies were designed to examine innovative or experimental approaches as opposed to developing evidence-based therapies for college students. Therefore, the current metaanalysis included only studies that examined full psychological treatments of depression in college student samples. In this metaanalysis, we examine whether psychological therapies are effective in the treatment of depression in college students. We also examine whether the effects of psychological treatments of depression in college students differ from those in adults in general.

METHODS

IDENTIFICATION OF STUDIES

We began with a database of 1,756 papers on the psychological treatment of depression that has been described in detail elsewhere[14] and has been used in a series of earlier published metaanalyses (www.evidencebasedpsychotherapies.org). The database is continuously updated and was developed through a comprehensive literature search (from 1966 to January 2015) in which 16,365 abstracts from PubMed (4,007 abstracts), PsycInfo (3,147 abstracts), Embase (5,912 abstracts), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (3,995 abstracts) were examined. These abstracts were identified by combining terms indicative of psychological treatment and depression (both MeSH-terms and text words). Primary studies from earlier meta-analyses of psychological treatment for depression also were checked to ensure that no published studies had been omitted.

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

We included randomized trials on the acute treatment of depression among college students, in which the effects of a psychological treatment were compared with a control group (waiting list, care-as-usual, placebo, or other). Treatments could be delivered individually, in a group, in a guided self-help format, or as Internet-based intervention (with human support). Unguided interventions without any human support were not included. Studies in which two or more types of treatment were compared to each other were excluded if no control condition was available. We only included studies in which interventions were examined that had treatment of depression as their primary goal, and experimental manipulations in depressed students in which a full psychological treatment was not examined were not included.

We compared treatment effect sizes in these trials conducted among college students with those in other trials in which a psychological treatment of depression was compared with a control condition in an unselected group of depressed adults. Studies on specific target groups (e.g., older adults, patients with comorbid general medical disorders, women with postpartum depression, etc.) were excluded from this comparison as were studies of inpatients, patients with chronic and treatment-resistant depression, patients with coexisting marital problems, and patient groups made up exclusively of those with other comorbid mental disorders.

RISK OF BIAS ASSESSMENT

We assessed the risk of bias of the studies according to four basic criteria suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions:[15] (i) adequate sequence generation (the randomization scheme was generated correctly); (ii) allocation to conditions by an independent (third) party; (iii) assessors blind to outcomes; and (iv) completeness of follow-up data. Data extraction was conducted by two independent researchers. Two independent raters assessed the risk of bias and resulting disagreements were resolved until agreement was reached.

METAANALYSES

For each comparison between a psychological treatment and a control condition we calculated the effect size that indicated the difference between the two conditions at posttest, adjusted for small sample bias (Hedges’ g).[16] Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting (at posttest) the average score of the treatment group from the average score of the control group and then dividing the result by the pooled standard deviations of the two groups. We only used those instruments that explicitly measured symptoms of depression, such as the Beck Depression Inventory[17] (BDI) or the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression[18] (HRSD). If more than one depression measure was used, the mean of the effect sizes was calculated, so that each study provided only one effect size.

We used the computer program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3.3.070; Biostat, 2014) to calculate pooled mean effect sizes. As we expected considerable heterogeneity, we calculated mean effect sizes using a random effects model. Numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT) were calculated using the formulae provided by Kraemer and Kupfer.[19] In all analyses we calculated the I2-statistic as an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages (25% indicates low, 50% moderate, and 75% high heterogeneity).[20] We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CI) around I2[21] using the noncentral Chi squared-based approach within the Heterogi module for Stata.[22]

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to the mixed effects model,[23] in which studies within subgroups are pooled with the random effects model, while tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted with the fixed effects model. Multivariate and bivariate metaregression analyses were conducted according to the procedures developed by Borenstein and colleagues.[23] Publication bias was examined with Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure,[24] which yields an estimate of the effect size after accounting for publication bias. We also conducted Egger’s test for the asymmetry of the funnel plot.

RESULTS

SELECTION AND INCLUSION OF STUDIES

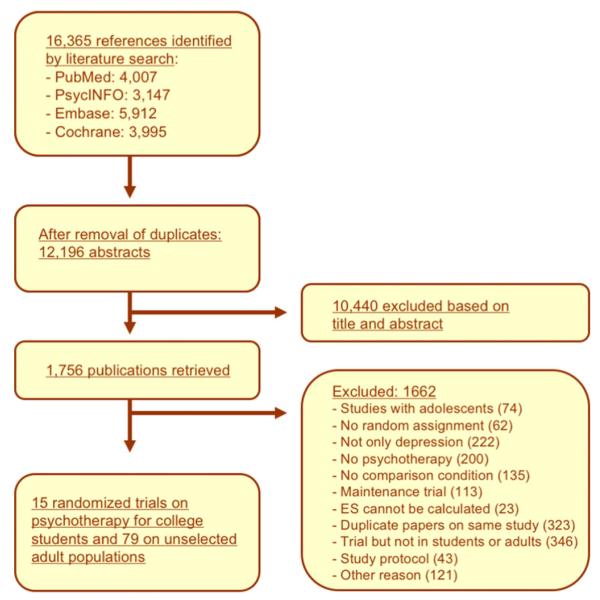

After examining a total of 16,365 abstracts (12,196 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 1,756 full-text papers for further consideration. We excluded 1,661 of the retrieved papers for the main analyses. The reasons for excluding studies are given in Figure 1. Fifteen studies on psychological treatments for college students met inclusion criteria (main analyses). Another 79 studies (with 121 comparisons between a treatment and a control group) on psychological treatments for unselected adults were included (for the comparison of effect sizes of psychological treatments of college students versus unselected adults with depression). This makes a total of 94 studies that were included in the analyses. Figure 1 presents a flowchart describing the inclusion process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion of studies.

CHARACTERISTICS OF INCLUDED STUDIES

Selected characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. In the 15 included studies among college students, a total of 922 students participated (therapy conditions = 479, control conditions = 443), with a total of 22 comparisons between treatment and control conditions examined (one comparison = one study, two comparisons = three studies, and three comparisons = two studies). The average number of patients per condition was 26.

TABLE 1.

Selected characteristics of studies comparing psychological treatments of depression in college students with control conditions

| Comp | Definition of depression |

Conditions | N | Nsess | Form | RoBa) | Country | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gawrysiak[34] | CR | 1st year Psychology students; screening instrument |

BDI-II ≥ 14 | 1. BA 2. CAU |

14 16 |

1 | Ind | −−sr+ | USA |

| Hamamci[35] | 0 | Announcements | BDI ≥ 19 | 1. Psychodrama CBT 2. CBT 3. CAU |

10 10 11 |

11 | Grp | −−sr− | Turkey |

| Hamdan- Mansour[36] |

$ | Announcements | BDI ≥ 15 | 1. CBT 2. CAU |

44 36 |

10 | Grp | −+sr− | Jordan |

| Hayman[37] b) | 0 | Announcements | BDI 13–30 | 1. Social skills training 2. Waiting list |

16 12 |

8 | Grp | +−sr− | USA |

| Hogg[38] | 0 | Students seeking treatment at college counseling center |

Mood disorder + BDI ≥ 14 |

1. CBT 2. Interpers group ther 3. Waiting list |

13 14 10 |

8 8 |

Grp Grp |

−−sr− | USA |

| Pace[39] | CR | Undergraduate educational psychology classes |

BDI 10–29 | 1. CBT 2. Waiting list |

31 43 |

7 | Ind | −−sr− | USA |

| Pecheur[40] | 0 | Announcements; Christian students from different years |

MDD (RDC) + BDI ≥ 15 + HAM-D ≥ 20 |

1. CBT 2. Religious CBT 3. Waiting list |

7 7 7 |

8 8 |

Ind Ind |

−−+− | USA |

| Peden[41] | 0 | Announcements; All female college students |

BDI ≥ 16 or CES-D ≥ 16 |

1. CBT 2. CAU |

46 46 |

6 | Grp | −−sr− | USA |

| Rohde[42] | $ | Direct mailings to 1st/2nd year students | 2 symptoms, no MDD |

1. CBT 2. Brochure control |

27 33 |

6 | Grp | +−++ | USA |

| Seligman[43] | $ | Mail to all incoming students of one university |

BDI 9–24 | 1. CBT 2. No treatment |

102125 | 8 | Grp | −−+− | USA |

| Shaw[44] | 0 | Referral from college health center, or self-referral |

BDI ≥ 18 | 1. CBT 2. BA 3. Supportive therapy 4. Waiting list |

8 8 8 8 |

8 8 8 |

Grp Grp Grp |

−−sr− | USA |

| Taylor[45] | 0 | Announcements | BDI ≥ 13 + D-30 ≥ 70 |

1. CT 2. BA 3. CBT 4. Waiting list |

7 7 7 7 |

6 6 6 |

Ind Ind Ind |

−−sr− | Canada |

| Turner[46] | 0 | Announcements | DACL T-score ≥ 70 |

1. BA 2. Attention control |

17 17 |

5 | Ind | −−sr− | USA |

| Tyson[47] | CR or $ |

Experimental pool of students + announcements |

MMPI-d T-score ≥ 60 |

1. Gestalt therapy 2. Attention placebo |

11 11 |

4 | Grp | −−sr− | USA |

| Vazquez[48] | 0 | Announcements | CES-D ≥ 16 + no MDD |

1. CBT 2. Control (relaxation) |

65 61 |

8 | Grp | −−sr+ | Spain |

In this column a positive (+), or negative (−) sign is given for four risk of bias criteria, respectively: allocation sequence; concealment of allocation to conditions; blinding of assessors; and intention-to-treat analyses.

In this study 4 of the 26 included subjects were not college students.

$, compensation by money; BA, behavioral activation; CAU, care as usual; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; Comp, compensation; CR, compensation by study credits; Form, format; Grp, group; Ind, individual; Interpers, interpersonal; MDD, major depressive disorder; Nsess, number of sessions; RoB, risk of bias; Sr, self-report; Ther, therapy.

Students received compensation for participating in the study (money or study credits) in six of the 15 studies. Students were recruited through: (a) announcements in college newspapers (nine studies), (b) completion of self-report depression measures (four studies), and (c) referrals from college health services (two studies).

In 14 of the 22 comparisons between a treatment and a control condition, cognitive behavior therapy was used as the intervention, four used behavioral activation, and the remainder used another type of treatment. Fourteen comparisons used a group treatment format and eight studies utilized individual treatment. The number of treatment sessions ranged from one to 11. For the control group, six studies used a waiting list, five studies used care-as-usual, and four used another control group. Thirteen studies were conducted in the United States.

Selected characteristics of the 122 comparisons between treatment and control groups in adults are presented in Appendix A and the references for the 79 studies are given in Appendix B.

RISK OF BIAS

The risk of bias in most studies was considerable. Only one of the 15 studies reported an adequate sequence generation method. Two of the 15 studies reported allocation to conditions by an independent (third) party. Twelve used only self-reported treatment outcomes and one of the three remaining studies reported using blinded outcome assessors. In five studies intent-to-treat analyses (completeness of follow-up data) were conducted. None of the included 15 studies met all quality criteria. One study met three criteria, four others met two criteria, and the other 10 met only one of the four criteria.

EFFECTS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF COLLEGE STUDENTS VERSUS CONTROL GROUPS

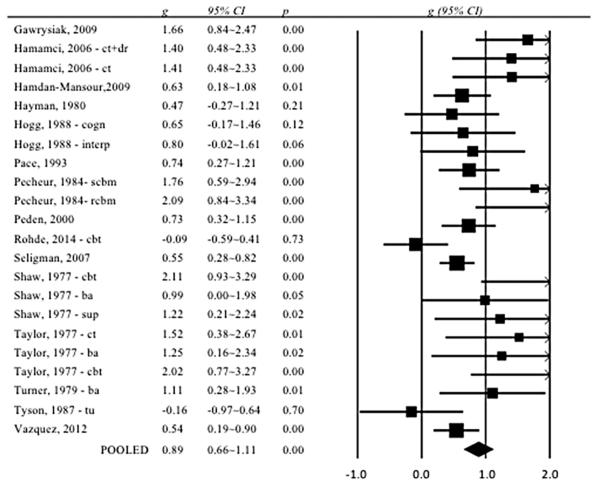

From the 15 included studies, we compared the effects of treatment with a control group in 22 comparisons. The overall effect size was g = 0.89 (95% CI: 0.66~1.11), which corresponds with a NNT of 2.13. Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 57; 95% CI: 23~72).

Inspection of a forest plot of the effect sizes and 95% CIs (Fig. 2) indicated that there were potential outliers. Exclusion of the two effect sizes that did not overlap with the 95% CI of the pooled effect size resulted in a larger effect size (g = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.75~1.17; NNT = 1.99) as well as a reduction in heterogeneity (I2 = 42; 95% CI: 0~65).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of effect sizes of randomized trials comparing psychological treatments for college students with control groups: Hedges’ g.

Given that five studies included multiple psychological treatments that were considered in the same analysis, which may have (a) resulted in an artificial reduction of heterogeneity and (b) affected the pooled effect size, we conducted an analysis in which we included only one effect size per study (either the largest or the smallest effect size in each study). As can be seen from Table 2, the resulting effect sizes were somewhat smaller and more heterogeneous than the overall effect sizes.

TABLE 2.

Effects of psychological treatments for depressed college students compared with control groups: Hedges’ ga

| N comp | g | 95% CI | I2 | 95% CI | P b | NNT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 22 | 0.89 | 0.66~1.11 | 57 | 23-72 | 2.13 | ||

| Two outliers excluded | 20 | 0.96 | 0.75~1.17 | 42 | 0~65 | 1.99 | ||

| Only BDI | 17 | 1.02 | 0.78~1.26 | 46 | 0~68 | 1.89 | ||

| One ES per study (highest) | 15 | 0.79 | 0.53~1.05 | 64 | 29~78 | 2.36 | ||

| One ES per study (lowest) | 15 | 0.70 | 0.48~0.93 | 53 | 0~73 | 2.63 | ||

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||||

| Compensation | Yes | 6 | 0.53 | 0.18~0.88 | 71 | 0~85 | 0.01 | 3.42 |

| No | 16 | 1.08 | 0.81~1.36 | 36 | 0~64 | 1.81 | ||

| Recruitment | Announcements | 13 | 0.96 | 0.65~1.26 | 52 | 0~73 | 0.38 | 1.99 |

| Clinical referrals | 5 | 1.07 | 0.53~1.62 | 12 | 0~68 | 1.82 | ||

| Screening | 4 | 0.63 | 0.17~1.08 | 79 | 4~90 | 2.91 | ||

| Depression | Mood disorder | 4 | 1.16 | 0.57~1.76 | 44 | 0~80 | 0.06 | 1.70 |

| Self-report | 16 | 0.95 | 0.69~1.20 | 49 | 0~70 | 2.01 | ||

| Subthreshold | 2 | 0.26 | −0.31~0.82 | 75 | xxx) | 6.85 | ||

| Psychological treatment | CBT | 14 | 0.88 | 0.61~1.14 | 64 | 25~78 | 0.19 | 2.15 |

| BA | 4 | 1.27 | 0.69~1.84 | 0 | 0~68 | 1.59 | ||

| Other | 4 | 0.54 | −0.01~1.08 | 40 | 0~79 | 3.36 | ||

| Format | Group | 14 | 0.66 | 0.43~0.90 | 50 | 0~71 | 0.003 | 2.78 |

| Individual | 8 | 1.35 | 0.96~1.73 | 27 | 0~67 | 1.52 | ||

| Control group | Waiting list | 12 | 1.13 | 0.81~1.46 | 30 | 0~64 | 0.02 | 1.74 |

| Care-as-usual | 6 | 0.90 | 0.55~1.25 | 54 | 0~80 | 2.10 | ||

| Other | 4 | 0.33 | −0.10~0.76 | 66 | 0~86 | 5.43 |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001.

CI, confidence interval; Ncomp, number of comparisons; NNT, numbers-needed-to-treat.

According to the random effects model.

The P-values in this column indicate whether the difference between the effect sizes in the subgroups is significant.

We also calculated the effect sizes based on the BDI (no other measure was used in more than three studies). As can be seen in Table 2, the effect size based on the BDI only was somewhat higher than the overall pooled effect size (g = 1.02; 95% CI: 0.78~1.26; NNT 1.89).

Inspection of the funnel plot suggested considerable publication bias. Egger’s test of the intercept was significant (intercept: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.00~3.28; P = 0.0004). Duvall and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure indicated that eight studies might be missing due to publication bias and that the pooled effect size would decrease to g = 0.61 (95% CI: 0.37~0.85) if these presumably negative studies were included.

SUBGROUP ANALYSES

We conducted a series of subgroup analyses to examine whether characteristics of the studies were associated with effect sizes (Table 2). We found no indication that type of recruitment of students (through announcements in media, referrals from clinical services, or systematic screening), definition of depression (diagnosed mood disorder, scoring above a cut-off on a self-report measure, or subthreshold depression), or type of treatment (CBT, BAT, or other) was significantly associated with the effect size. We did, however, find that the effect size was significantly larger when the students were not compensated (through money or study credits; P = 0.01). In addition, individual therapy was significantly more effective than group therapy (P = 0.003), and the type of control group was significantly associated with the effect size (P = 0.02). Because almost all studies had a comparable risk of bias (score 1 or 2), we did not conduct a separate analysis for variation in estimated effect size as a function of the level of risk of bias.

EFFECTS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF COLLEGE STUDENTS VERSUS ADULTS IN GENERAL

The above results among college students were compared with the results of parallel analyses carried out in the 79 studies of treatments for depressed adults in general. The estimated pooled effect size found for adults across the 121 comparisons in these 79 studies (g = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.69~0.88; I2 = 73; 95% CI: 67~77; NNT = 2.36) did not differ significantly from the pooled effect size found among college students (g = 0.89, P = 0.38).

As aggregate comparison of effect sizes between college students and adults might be influenced by differences in treatment type and format, study quality, or other design features, we conducted a multivariate metaregression analysis in which we adjusted for all study characteristics extracted (Table 3). To avoid collinearity, we first calculated the correlation among all study variables, and results indicated no association was higher than r = 0.60. Therefore, all study variables were included in the model. After this, a multivariate metaregression analysis was conducted with the effect size as the dependent variable. Predictors included a dummy variable indicating whether the study was aimed at college students or unselected adult populations as well as the other characteristics of the studies, participants, and interventions. All variables were entered simultaneously in the model (Table 3). The effect of the dummy variable indicating whether the study was aimed at college students or unselected adult populations was not significant (P = 0.64), again suggesting the effects in these groups are comparable.

TABLE 3.

Standardized regression coefficients of characteristics of studies on psychological treatment of depression in college students and unselected adult populations: Multivariate metaregression analyses

| Coef. | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students vs adults in general (dummy) | 0.08 | −0.25~0.41 | 0.64 | |

| Diagnosis | • Mood disorder | Ref. | ||

| • Self-report | −0.15 | −0.38~0.08 | 0.20 | |

| • Subthreshold | −0.41 | −1.01~0.18 | 0.17 | |

| Type of treatment | • CBT | Ref. | ||

| • BAT | 0.43 | −0.01~0.87 | 0.06 | |

| • Other | 0.04 | −0.17~0.25 | 0.71 | |

| Format | • Individual | Ref. | ||

| • Group | −0.05 | −0.30~0.20 | 0.68 | |

| • Guided self-help | −0.20 | −0.52~0.11 | 0.20 | |

| Number of sessions (continuous) | −0.02 | −0.05~0.01 | 0.16 | |

| Control group | • Waiting list | Ref. | ||

| • Care-as-usual | −0.34 | −0.61~−0.07 | 0.01 | |

| • Other | −0.39 | −0.67~−0.11 | 0.01 | |

| Risk of bias (continuous) | −0.21 | −0.32~−0.10 | 0.00 | |

| Publication year (continuous) | 0.01 | 0.00~0.03 | 0.02 | |

| Intercept | −27.95 | −52.15~−3.75 | 0.02 | |

DISCUSSION

We conducted a metaanalysis of randomized trials examining the effects of psychological treatments of depression in college students. We identified 15 trials satisfying our inclusion criteria and comparing a psychological treatment to a control group. These trials suggest that the effects of psychological treatment in college students are in the range conventionally considered large (i.e. g > 0.8[25]). At the same time, none of the studies met all criteria for low risk of bias and only one met three of the four criteria. This implies that the results should be interpreted with caution.

We compared the studies in college students with those in unselected populations of adults with depression (which did include studies with low risk of bias). In multivariate metaregression analyses—which adjusted for the characteristics of the population, the interventions, and the study—we found no indication that effect sizes differed from those in unselected populations of adults. Despite differences in the quality of interventions in college students, these results suggest that effects found in adults may be generalizable to depressed college students.

We hypothesized that psychological treatment in students may differ from adult populations because students have higher levels of cognitive functioning and IQ, are more often experiencing a first episode, and may more often have a bipolar disorder instead of a depressive disorder. We found no evidence, however, that there is a difference in effects of treatments between college students and adults in general, so this investigation does not support these hypotheses.

In subgroup analyses, our results indicated that compensating students for participating in the trial resulted in lower effects. We could not verify this in the larger group of studies in unselected populations of adults, as few of these studies compensated participants (and course credit is not feasible). This finding was not anticipated, and it may be spurious. However, the need for remuneration may underscore a lack of intrinsic motivation in study participants (i.e., completing intervention for extrinsic gains). It is well-documented that college students perceive a significant number of barriers in seeking help for mental health problems (see[26,27]). Conversely, those who participated without receiving compensation may be more internally motivated to alleviate depressive symptoms.

The subgroup analyses also revealed that individual treatment was more effective than group therapy among college students. However, in the metaregression analyses, which included a larger sample of studies, we did not find any indication that treatment format was associated with effect size after adjustment for other characteristics of the studies. These results should therefore be considered with caution.

We also found that type of control group is significantly associated with the effect size, with waiting lists resulting in significantly higher effect sizes relative to other types of control groups. This finding remained significant in the multivariate metaregression analyses and is in line with previous metaanalyses.[28,29]

The results of this metaanalysis should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. First, risk of bias in the included studies was high. To address this limitation, we compared the results with a larger sample of studies in adults. Although this provides a statistical adjustment, it cannot completely compensate for the limitations in study designs in college students. Second, few studies examined the long-term effects of the treatments and the effect sizes we focused on here were ones that examined episode resolution rather than risk of recurrence. Third, the number of studies in this population was relatively small, which reduced our ability to carry out powerful moderator analyses. Finally, in this meta-analysis we could only compare studies in college students with those in adult populations. It may have been preferable to compare college students and same-aged nonstudent young adults in order to determine whether education is a key moderator. Unfortunately, no studies have been completed that specifically target this nonstudent population.

Despite these limitations, the results suggest that the effects of psychological treatments of depression among college students are significant and comparable to those of depressed adults, suggesting that systematic efforts to expand detection, outreach, and treatment of depressed college students with standard treatments are warranted. Such efforts could have important societal effects, as college students represent the future leaders of society and their success is critical for societal human capital development, while depression is an important risk factor that, if untreated or inadequately treated, can have profoundly negative effects on this human capital development. The results reported here also highlight the importance of conducting higher quality treatment studies among college students in the future and, in addition, collecting sufficient baseline information to allow future analyses to go beyond the aggregate level of analysis to examine heterogeneity of treatment effects and to explore the possibility that different types of treatment might be optimal for different types of students.

It is well-established that individual, group, and guided self-help treatments are effective in the treatment of depression, with no major differences between the effects of these different formats.[30–32] It is also known that for some depressed individuals even unguided self-help may be effective.[33] Currently, it is not known which patients respond to which treatment or treatment format. It is important, therefore, to conduct large surveys among students to explore potential predictors of the outcomes of therapies, to develop models to predict the most efficient treatment for individual students, and to test these models in new randomized trials examining if they can strengthen treatment outcome and improve efficiency of treatments.

Appendix A. Selected characteristics of comparisons between treatment and control groups in adults (N = 121)

| Recr | Diagn | Type | Control | Format | Nsess | RoB | Countr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allart et al.[1] | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | cau | grp | 12 | 1 | EU |

| Andersson et al.[2] | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | other | gsh | 5 | 4 | EU |

| Barber et al.[3] | Comm | Mood | DYN | other | ind | 20 | 3 | US |

| Barrera[4] | Comm | Cut-off | BAT | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | US |

| Berger et al.[5] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 10 | 4 | EU |

| Bohlmeijer et al.[6] | Comm | Cut-off | Other | wl | grp | 8 | 4 | EU |

| Bolton et al.[7] | Other | Mood | IPT | cau | grp | 16 | 3 | Other |

| Bowman et al.[8]—cogn | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | wl | gsh | 4 | 0 | US |

| Bowman et al.[8]—se | Comm | Cut-off | PST | wl | gsh | 4 | 0 | US |

| Brown and Lewinsohn[9]—grp | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 12 | 1 | US |

| Brown and Lewinsohn[9]—gsh | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 12 | 1 | US |

| Brown and Lewinsohn[9]—ind | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 12 | 1 | US |

| Carlbring et al.[10] | Comm | Mood | Other | wl | gsh | 7 | 4 | EU |

| Carrington[11]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 12 | 1 | US |

| Carrington[11]—dyn | Comm | Mood | DYN | wl | ind | 12 | 1 | US |

| Castonguay et al.[12] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 16 | 1 | US |

| Chan[13]–cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 10 | 2 | Other |

| Chan[13]–mbt | Comm | Mood | Other | wl | ind | 10 | 2 | Other |

| Cullen[14] | Comm | Mood | BAT | wl | ind | 10 | 1 | US |

| DeRubeis et al.[15] | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | ind | 14 | 2 | US |

| Dimidjian et al.[16]—ba | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | ind | 16 | 3 | US |

| Dimidjian et al.[16]—ct | Comm | Mood | BAT | other | ind | 16 | 3 | US |

| Dowrick et al.[17]—cwd | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | grp | 12 | 4 | UK |

| Dowrick et al.[17]—pst | Comm | Mood | PST | cau | ind | 6 | 4 | UK |

| Ekers et al.[18] | Comm | Mood | BAT | cau | ind | 12 | 4 | UK |

| Elkin et al.[19]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | ind | 16 | 2 | US |

| Elkin et al.[19]—ipt | Comm | Mood | IPT | other | ind | 16 | 2 | US |

| Epstein[20] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | US |

| Fledderus et al.[21]—act-e | Comm | Mood | Other | wl | gsh | 9 | 3 | EU |

| Fledderus et al.[21]—act-m | Comm | Mood | Other | wl | gsh | 9 | 3 | EU |

| Gehr[22] | Comm | Mood | Other | other | ind | 7 | 1 | EU |

| Hegerl et al.[23] | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | other | grp | 10 | 4 | EU |

| Horrell et al.[24] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 4 | 4 | UK |

| Jamison and Scogin[25] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 4 | 0 | EU |

| Jarrett et al.[26] | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | ind | 20 | 3 | EU |

| Johansson et al.[27] | Comm | Mood | DYN | other | gsh | 9 | 4 | EU |

| Johansson et al.[28]—stand | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | gsh | 8 | 3 | EU |

| Johansson et al.[28]—tayl | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | gsh | 8 | 3 | EU |

| Kessler et al.[29] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 10 | 4 | EU |

| King et al.[30]—cbt | Clin | Cut-off | CBT | cau | ind | 6 | 3 | EU |

| King et al.[30]—sup | Clin | Cut-off | SUP | cau | ind | 6 | 3 | UK |

| Kivi et al.[31] | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | gsh | 7 | 2 | EU |

| Klein et al.[21] | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | grp | 12 | 1 | US |

| Korrelboom et al.[33] | Comm | Mood | other | cau | grp | 8 | 3 | EU |

| Krampen[34]—aut | Comm | Mood | other | wl | ind | 20 | 1 | EU |

| Krampen[34]—ind | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 20 | 1 | EU |

| Liu et al.[35] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 4 | 1 | EU |

| Lynch et al.[36] | Comm | Cut-off | PST | cau | other | 6 | 1 | US |

| Lynch et al.[37] | Comm | Mood | PST | cau | other | 6 | 1 | EU |

| MacPherson et al.[38] | Comm | Mood | SUP | cau | ind | 12 | 4 | EU |

| Maina et al.[39]—bdt | Comm | Mood | DYN | wl | ind | 20 | 2 | EU |

| Maina et al.[39]—bsp | Comm | Mood | SUP | wl | ind | 20 | 2 | EU |

| McKendree-Smith[40]—beh | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 8 | 1 | EU |

| McKendree-Smith[40]—cogn | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 8 | 1 | EU |

| Miller and Weissman[41] | Comm | Mood | IPT | cau | other | 12 | 1 | EU |

| Mohr et al.[42] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 18 | 4 | EU |

| Morris[43] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 6 | 1 | Other |

| Mukhtar and Oei[44] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | Other |

| Murphy et al.[45] | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | ind | 20 | 1 | US |

| Mynors-Wallis[46] | Comm | Mood | PST | other | ind | 6 | 2 | UK |

| Naeem et al.[47] | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | gsh | 7 | 2 | EU |

| Nezu and Perri[48]—pf | Comm | Mood | PST | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | US |

| Nezu and Perri[48]—pst | Comm | Mood | PST | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | US |

| Nezu[49]—apst | Comm | Mood | PST | wl | grp | 10 | 1 | US |

| Nezu[49]—pst | Comm | Mood | PST | wl | grp | 10 | 1 | US |

| Omidi et al.[50]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | grp | 8 | 1 | EU |

| Omidi et al.[50]—mbct | Comm | Mood | MBCT | cau | grp | 8 | 1 | EU |

| Perini et al.[51] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 6 | 2 | Other |

| Pots et al.[52] | Comm | Mood | MBCT | wl | grp | 11 | 4 | EU |

| Power and Freeman[53]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | ind | 16 | 2 | UK |

| Power and Freeman[53]—ipt | Comm | Mood | IPT | cau | ind | 16 | 2 | UK |

| Propst et al.[54]—nrct-nt | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | wl | ind | 19 | 1 | US |

| Propst et al.[54]—nrct-rt | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | wl | ind | 19 | 1 | US |

| Propst et al.[54]—rct-nt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 19 | 1 | US |

| Propst et al.[54]-rct-rt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 19 | 1 | US |

| Rehm et al.[55]—sm | Comm | Cut-off | other | wl | grp | 7 | 1 | US |

| Rehm et al.[55]—sm+se | Comm | Cut-off | other | wl | grp | 7 | 1 | US |

| Rehm et al.[55]—sm+sr | Comm | Cut-off | other | wl | grp | 7 | 1 | US |

| Rohen[56] | Comm | Cut-off | CBT | wl | gsh | 4 | 2 | US |

| Ross and Scott[57] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | other | 12 | 1 | UK |

| Rude[58] | Comm | Mood | other | wl | grp | 12 | 1 | US |

| Schmidt and Miller[59]—gsh | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 8 | 1 | US |

| Schmidt and Miller[59]—ind | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 8 | 1 | US |

| Schmidt and Miller[59]—lgrp | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | US |

| Schmidt and Miller[59]—sgrp | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 8 | 1 | US |

| Schmitt[60]—pst | Comm | Mood | PST | wl | grp | 12 | 0 | US |

| Schmitt[60]—sst | Comm | Mood | other | wl | grp | 12 | 0 | US |

| Schulberg et al.[61] | Comm | Mood | IPT | cau | ind | 16 | 2 | US |

| Scott and Stradling[64]—cgt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 12 | 2 | UK |

| Scott and Stradling[64]—ict | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 12 | 2 | UK |

| Scott and Freeman[62]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | ind | 16 | 2 | UK |

| Scott and Freeman.[62]—sup | Comm | Mood | SUP | cau | ind | 16 | 2 | UK |

| Scott et al.[63] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 6 | 1 | UK |

| Selmi et al.[65]—ccbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 6 | 2 | US |

| Selmi et al.[65]—icbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 6 | 2 | US |

| Skinner[66]—bat | Comm | Mood | BAT | other | ind | 5 | 1 | US |

| Skinner[66]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | other | ind | 5 | 1 | US |

| Smit et al.[67] | Clin | Mood | CBT | cau | ind | 14 | 3 | EU |

| Sudweeks[68]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 6 | 1 | EU |

| Sudweeks[68]—hypn | Comm | Mood | other | wl | ind | 6 | 1 | EU |

| Sudweeks[68]—hypn+cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 6 | 1 | EU |

| Teasdale et al.[69] | Comm | Mood | CBT | cau | ind | 15 | 1 | EU |

| Titov et al.[70]—icbt-techn | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 6 | 2 | Other |

| Titov et al.[70]—icbt-ther | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 6 | 2 | Other |

| Vernmark et al.[71]—email | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 7 | 4 | EU |

| Vernmark et al.[71]—self-h | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 7 | 4 | EU |

| Warmerdam et al.[72]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 8 | 4 | EU |

| Warmerdam et al.[72]—pst | Comm | Cut-off | PST | wl | gsh | 5 | 4 | EU |

| Weissman[73] | Comm | Mood | IPT | other | ind | 16 | 1 | EU |

| Wierzbicki and Bartlett[74]—grp |

Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 6 | 1 | US |

| Wierzbicki and Bartlett[74]—ind |

Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 6 | 1 | US |

| Wilson et al.[75]—beh | Comm | Mood | BAT | wl | ind | 8 | 0 | Other |

| Wilson et al.[75]—cogn | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 8 | 0 | Other |

| Wollersheim and Wilson[76]—cop |

Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 10 | 1 | US |

| Wollersheim and Wilson[76]—gsh |

Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 10 | 1 | US |

| Wollersheim and Wilson[76]—sup |

Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 10 | 1 | US |

| Wong II[77] | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | grp | 10 | 2 | Other |

| Wright et al.[78]—cbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | ind | 9 | 2 | US |

| Wright et al.[78]—ccbt | Comm | Mood | CBT | wl | gsh | 9 | 2 | US |

| Zu et al.[79] | Clin | Mood | CBT | cau | ind | 20 | 2 | Other |

BAT, behavioral activation therapy; Cau, care-as-usual; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; Clin, clinical samples only; Comm, community recruitment; Countr, country; Diagn, diagnosis of depression; DYN, psychodynamic therapy; Grp, group format; Gsh, guided self-help; Ind, individual format; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy; Mood, mood disorder; Nsess, number of sessions; PST, problem-solving therapy; Recr, recruitment; RoB, risk of bias; wl, waiting list.

Appendix B. References for trials comparing psychological treatments for adult depression and control groups (N = 79)

- 1.Allart-van Dam E, Hosman CMH, Hoogduin CAL, Schaap CPDR. The coping with depression course: short-term outcomes and mediating effects of a randomized controlled trial in the treatment of subclinical depression. Behav Ther. 2003;34(3):381–396. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson G, Bergström J, Holländare F, Carlbring P, Kaldo V, Ekselius L. Internet-based self-help for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:456–461. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber JP, Barrett MS, Gallop R, Rynn MA, Rickels K. Short-term dynamic psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):66–73. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m06831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrera M. An evaluation of a brief group therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47(2):413–415. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger T, Hämmerli K, Gubser N, Andersson G, Caspar F. Internet-based treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self-help. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(4):251–266. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.616531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohlmeijer ET, Fledderus M, Rokx T a. JJ, Pieterse ME. Efficacy of an early intervention based on acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with depressive symptomatology: evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(1):62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3117–3124. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman D, Scogin F, Lyrene B. The efficacy of self-examination therapy and cognitive bibliotherapy in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Psychother Res. 1995;5(2):131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM. A psychoeducational approach to the treatment of depression: comparison of group, individual, and minimal contact procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52(5):774–783. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlbring P, Hägglund M, Luthström A, et al. Internet-based behavioral activation and acceptance-based treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2–3):331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrington CH. A comparison of cognitive and analytically oriented brief treatment approaches to depression in black women. University of Maryland College Park; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castonguay LG, Schut AJ, Aikens DE, et al. Integrative cognitive therapy for depression: a preliminary investigation. J Psychother Integr. 2004;14(1):4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan AS, Wong QY, Sze SL, Kwong PPK, Han YMY, Cheung M-C. A Chinese Chan-based mind-body intervention for patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1–3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullen JM. Testing the Effectiveness of Behavioral Activation Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Unipolar Depression. Western Michigan University; Michigan: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs. medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(4):658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowrick C, Dunn G, Ayuso-Mateos JL, et al. Problem solving treatment and group psychoeducation for depression: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Outcomes of Depression International Network (ODIN) Group. BMJ. 2000;321(7274):1450–1454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekers D, Richards D, McMillan D, Bland JM, Gilbody S. Behavioural activation delivered by the non-specialist: phase II randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(1):66–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.079111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971–982. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110013002. discussion 983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein D. Aerobic Activity Versus Group Cognitive Therapy: An Evaluative Study of Contrasting Interventions for the Alleviation of Clinical Depression. University of Reno; Nevada: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fledderus M, Bohlmeijer ET, Pieterse ME, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42(3):485–495. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gehr PD. Guided Imagery As a Treatment Intervention for Depression. United States International University; San Diego, CA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegerl U, Hautzinger M, Mergl R, et al. Effects of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in depressed primary-care patients: a randomized, controlled trial including a patients’ choice arm. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(1):31–44. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horrell L, Goldsmith KA, Tylee AT, et al. Oneday cognitive-behavioural therapy self-confidence workshops for people with depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):222–233. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.121855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamison C, Scogin F. The outcome of cognitive bibliotherapy with depressed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(4):644–650. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D, Witt-Browder A, Kraft D, Risser RC. Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(5):431–437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansson R, Ekbladh S, Hebert A, et al. Psychodynamic guided self-help for adult depression through the internet: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e38021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansson R, Sjöberg E, Sjögren M, et al. Tailored vs. standardized internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression and comorbid symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler D, Lewis G, Kaur S, et al. Therapist-delivered Internet psychotherapy for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 374(9690):628–634. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61257-5. 200922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King M, Sibbald B, Ward E, et al. Randomised controlled trial of non-directive counselling, cognitive-behaviour therapy and usual general practitioner care in the management of depression as well as mixed anxiety and depression in primary care. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4(19):1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kivi M, Eriksson MCM, Hange D, et al. Internet-based therapy for mild to moderate depression in Swedish primary care: short term results from the PRIM-NET randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2014;43(4):289–298. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.921834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein MH, Greist JH, Gurman AS, et al. A comparative outcome study of group psychotherapy vs. exercise treatments for depression. Int J Mental Health. 1984;13(3–4):148–176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korrelboom K, Maarsingh M, Huijbrechts I. Competitive memory training (COMET) for treating low self-esteem in patients with depressive disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(2):102–110. doi: 10.1002/da.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krampen G. Autogenes Training vor und begleitend zur methodenübergreifenden Einzelpsychotherapie bei depressiven Störungen. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie, Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 1997;45(2):214–232. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu ET-H, Chen W-L, Li Y-H, Wang CH, Mok TJ, Huang HS. Exploring the efficacy of cognitive bibliotherapy and a potential mechanism of change in the treatment of depressive symptoms among the Chinese: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Ther Res. 33(5):449–461. 200830. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynch D, Tamburrino M, Nagel R, Smith MK. Telephone-based treatment for family practice patients with mild depression. Psychol Rep. 2004;94(3):785–792. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3.785-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch DJ, Tamburrino MB, Nagel R. Telephone counseling for patients with minor depression: preliminary findings in a family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 1997;44(3):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacPherson H, Richmond S, Bland M, et al. Acupuncture and counselling for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maina G, Forner F, Bogetto F. Randomized controlled trial comparing brief dynamic and supportive therapy with waiting list condition in minor depressive disorders. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(1):43–50. doi: 10.1159/000082026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKendree-Smith NL. Cognitive and Behavioral Bibliotherapy for Depression: An Examination of Efficacy and Mediators and Moderators of Change. The University of Alabama; Alabama: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller L, Weissman M. Interpersonal psychotherapy delivered over the telephone to recurrent depressives. A pilot study. Depress Anxiety. 2002;16(3):114–117. doi: 10.1002/da.10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohr DC, Duffecy J, Ho J, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a manualized TeleCoaching protocol for improving adherence to a web-based intervention for the treatment of depression. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris NE. A Group Self-Instruction Method for the Treatment of Depressed Outpatients. University of Toronto; Toronto, Canada: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukhtar F, Oei TPS. Predictors of group cognitive behaviour therapy outcomes for the treatment of depression in Malaysia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2011;4(2):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy GE, Carney RM, Knesevich MA, Wetzel RD, Whitworth P. Cognitive behavior therapy, relaxation training, and tricyclic antidepressant medication in the treatment of depression. Psychol Rep. 1995;77(2):403–420. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson D. Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 310(6977):441–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.441. 199518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naeem F, Sarhandi I, Gul M, et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of a career supervised culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) based self-help for depression in Pakistan. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:224–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nezu AM, Perri MG. Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: an initial dismantling investigation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(3):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nezu AM. Efficacy of a social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(2):196–202. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Omidi A, Mohammadkhani P, Mohammadi A, Zargar F. Comparing mindfulness based cognitive therapy and traditional cognitive behavior therapy with treatments as usual on reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(2):142–146. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perini S, Titov N, Andrews G. Clinician-assisted Internet-based treatment is effective for depression: randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(6):571–578. doi: 10.1080/00048670902873722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pots WTM, Meulenbeek PAM, Veehof MM, Klungers J, Bohlmeijer ET. The efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a public mental health intervention for adults with mild to moderate depressive symptomatology: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Power MJ, Freeman C. A randomized controlled trial of IPT versus CBT in primary care: with some cautionary notes about handling missing values in clinical trials. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19(2):159–169. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Propst LR, Ostrom R, Watkins P, Dean T, Mashburn D. Comparative efficacy of religious and non-religious cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of clinical depression in religious individuals. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(1):94–103. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rehm LP, Kornblith SJ, O’Hara MW, Lamparski DM, Romano JM, Volkin JI. An evaluation of major components in a self-control therapy program for depression. Behav Modif. 1981;5(4):459–489. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rohen NA. Analysis of Efficacy and Mediators of Outcome in Minimal-Contact Cognitive Biblio-therapy Used in the Treatment of Depressive Symptoms. The University of Alabama; Alabama: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ross M, Scott M. An evaluation of the effectiveness of individual and group cognitive therapy in the treatment of depressed patients in an inner city health centre. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1985;35(274):239–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rude SS. Relative benefits of assertion or cognitive self-control treatment for depression as a function of proficiency in each domain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(3):390–394. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt MM, Miller WR. Amount of therapist contact and outcome in a multidimensional depression treatment program. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(5):319–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmitt SG. Clinical depression: a comparative outcome study of two treatment approaches. Fairleigh Dickinson University; Teaneck, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice. Eight-month clinical outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(10):913–919. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100061008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott AI, Freeman CP. Edinburgh primary care depression study: treatment outcome, patient satisfaction, and cost after 16 weeks. BMJ. 1992;304(6831):883–887. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6831.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott C, Tacchi MJ, Jones R, Scott J. Acute and one-year outcome of a randomised controlled trial of brief cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:131–134. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scott MJ, Stradling SG. Group cognitive therapy for depression produces clinically significant reliable change in community-based settings. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1990;18(01):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, Sorrell SP, Erdman HP. Computer-administered therapy for depression. MD Comput. 1991;8(2):98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skinner DA. Self-control of depression: a comparison of behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. United States International University; San Diego, CA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smit A, Kluiter H, Conradi HJ, et al. Short-term effects of enhanced treatment for depression in primary care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):15–26. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sudweeks C. Effects of cognitive group hypnotherapy in the alteration of depressogenic schemas. Washington State University; Washington: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teasdale JD, Fennell MJ, Hibbert GA, Amies PL. Cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:400–446. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Titov N, Andrews G, Davies M, McIntyre K, Robinson E, Solley K. Internet treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e10939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vernmark K, Lenndin J, Bjärehed J, et al. Internet administered guided self-help versus individualized e-mail therapy: a randomized trial of two versions of CBT for major depression. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(5):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, Riper H, Cuijpers P. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(4):e44. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Dimascio A, Neu C, Goklaney M, Klerman GL. The efficacy of drugs and psychotherapy in the treatment of acute depressive episodes. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(4B):555–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wierzbicki M, Bartlett TS. The efficacy of group and individual cognitive therapy for mild depression. Cogn Ther Res. 1987;11(3):337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson PH, Goldin JC, Charbonneau-Powis M. Comparative efficacy of behavioral and cognitive treatments of depression. Cogn Ther Res. 1983;7(2):111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wollersheim JP, Wilson GL. Group treatment of unipolar depression: a comparison of coping, supportive, bibliotherapy, and delayed treatment groups. Prof Psychol Res Practice. 1991;22(6):496–502. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wong DFK. Cognitive and health-related outcomes of group cognitive behavioural treatment for people with depressive symptoms in Hong Kong: randomized wait-list control study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(8):702–711. doi: 10.1080/00048670802203418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano AM, et al. Computer-assisted cognitive therapy for depression: maintaining efficacy while reducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1158–1164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zu S, Xiang Y-T, Liu J, et al. A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy, antidepressants, their combination and standard treatment for Chinese patients with moderate-severe major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

References marked with an asterisk are included in the meta-analysis.

- 1.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zivin K, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E. Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(3):180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reavley N, Jorm AF. Prevention and early intervention to improve mental health in higher education students: a review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(2):132–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Education NCfES . The Condition of Education 2007 (NCES 2007–064) U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berndt ER, Koran LM, Finkelstein SN, et al. Lost human capital from early-onset chronic depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):940–947. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mowbray CT, Megivern D, Mandiberg JM, et al. Campus mental health services: recommendations for change. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(2):226–237. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews G. It would be cost-effective to treat more people with mental disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(8):613–615. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2005;8(3):145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(7):1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuijpers P, Reynolds CF, Donker T, et al. Personalized treatment of adult depression: medication, psychotherapy, or both? A systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):855–864. doi: 10.1002/da.21985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prediction of response to medication and cognitive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):775–787. doi: 10.1037/a0015401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A. Interventions to reduce stress in university students: a review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrer L, Gulliver A, Chan JKY, et al. Technology-based interventions for mental health in tertiary students: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(5):e101. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G. Psychological treatment of depression: a meta-analytic database of randomized studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; [updated March 2011]. 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-analysis. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ioannidis JPA, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2007;335(7626):914–916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39343.408449.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orsini N, Bottai M, Higgins J, Buchan I. HETEROGI: Stata module to quantify heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. 2006 http://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s449201.htm.

- 23.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N, Zivin K. Mental health service utilization among college students in the United States. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(5):301–308. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182175123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM, et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(3):181–192. doi: 10.1111/acps.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohr DC, Spring B, Freedland KE, et al. The selection and design of control conditions for randomized controlled trials of psychological interventions. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(5):275–284. doi: 10.1159/000228248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–295. doi: 10.1002/wps.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, et al. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med. 2010;40(12):1943–1957. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, van Oppen P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(6):909–922. doi: 10.1037/a0013075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuijpers P, Donker T, Johansson R, et al. Self-guided psychological treatment for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.*; Gawrysiak M, Nicholas C, Hopko DR. Behavioral activation for moderately depressed university students: Randomized controlled trial. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(3):468–475. %* (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 35.*; Hamamci Z. Integrating psychodrama and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat moderate depression. Arts Psychother. 2006;33(3):199–207. %U http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197455606000189. [Google Scholar]

- 36.*; Hamdan-Mansour AM, Puskar K, Bandak AG. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on depressive symptomatology, stress and coping strategies among Jordanian university students. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(3):188–196. doi: 10.1080/01612840802694577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.*; Hayman PM, Cope CS. Effects of assertion training on depression. J Clin Psychol. 1980;36(2):534–543. doi: 10.1002/jclp.6120360226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.*; Hogg JA, Deffenbacher JL. A comparison of cognitive and interpersonal-process group therapies in the treatment of depression among college students. J Couns Psychol. 1988;35(3):304–310. %* (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 39.*; Pace TM, Dixon DN. Changes in depressive self-schemata and depressive symptoms following cognitive therapy. J Couns Psychol. 1993;40(3):288–294. [Google Scholar]

- 40.*; Pecheur DR, Edwards KJ. A comparison of secular and religious versions of cognitive therapy with depressed Christian college students. J Psychol Theol. 1984;12(1):45–54. %* (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 41.*; Peden AR, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Beebe LL. Reducing negative thinking and depressive symptoms in college women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2000;32(2):145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.*; Rohde P, Stice E, Shaw H, Gau JM. Cognitive-behavioral group depression prevention compared to bibliotherapy and brochure control: nonsignificant effects in pilot effectiveness trial with college students. Behav Res Ther. 2014;55:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.*; Seligman MEP, Schulman P, Tryon AM. Group prevention of depression and anxiety symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(6):1111–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.*; Shaw BF. Comparison of cognitive therapy and behavior therapy in the treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1977;45(4):543–551. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.45.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.*; Taylor FG, Marshall WL. Experimental analysis of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Cognit Ther Res. 1977;1(1):59–72. %U http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01173505. [Google Scholar]

- 46.*; Turner RW, Ward MF, Turner DJ. Behavioral treatment for depression: an evaluation of therapeutic components. J Clin Psychol. 1979;35(1):166–175. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197901)35:1<166::aid-jclp2270350127>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.*; Tyson GM, Range LM. Gestalt dialogues as a treatment for mild depression: time works just as well. J Clin Psychol. 1987;43(2):227–231. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198703)43:2<227::aid-jclp2270430210>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.*; Vázquez FL, Torres A, Blanco V, et al. Comparison of relaxation training with a cognitive-behavioural intervention for indicated prevention of depression in university students: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(11):1456–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]