Abstract

Although a suicide attempt history is among the single best predictors of risk for eventual death by suicide, little is known about the extent to which reporting of suicide attempts may vary by assessment type. The current study aimed to investigate the correspondence between suicide attempt history information obtained via a single-item self-report survey, multi-item self-report survey, and face-to-face clinical interview. Data were collected among a high-risk sample of undergraduates (N = 100) who endorsed a past attempt on a single-item prescreening survey. Participants subsequently completed a multi-item self-report survey, which was followed by a face-to-face clinical interview, both of which included additional questions regarding the timing and nature of previous attempts. Even though 100% of participants (n = 100) endorsed a suicide attempt history on the single-item prescreening survey, only 67% (n = 67) reported having made a suicide attempt on the multi-item follow-up survey. After incorporating ancillary information obtained from the in-person interview, 60% of participants qualified for a CDC-defined suicide attempt. Of the 40% who did not qualify for a CDC-defined suicide attempt, 30% instead qualified for no attempt, 7% an aborted attempt, and 3% an interrupted attempt. These findings suggest that single-item assessments of suicide attempt history may result in the misclassification of prior suicidal behaviors. Given that such assessments are commonly used in research and clinical practice, these results emphasize the importance of utilizing follow-up questions and assessments to improve precision in the characterization and assessment of suicide risk.

Keywords: Suicide, Suicide Risk Assessment, Suicide Attempt History

Nearly one million individuals die by suicide worldwide each year (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014), and suicide remains a leading cause of death in the United States, particularly among adolescents and young adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2015; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2002; Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis, & Irwin, 2006). To address this problem, both national and international health organizations have called for improvements in the study and delineation of risk and protective factors for suicide (IOM, 2002; WHO, 2014), especially since the evaluation of these factors is a key starting point in the suicide risk assessment process (Chu et al., 2015; Joiner et al., 1999). For example, this information guides risk level categorizations, supports clinical decision-making, and informs emergency referral procedures (Bernert, Hom, & Roberts, 2014; Bryan & Rudd, 2006; Chu et al., 2015; Joiner et al., 1999). Accurate assessment and detection of risk and protective factors also gate intervention opportunity since those deemed to be at elevated risk can then be encouraged to seek mental health care services, connected with evidence-based treatment, or recommended for psychiatric hospitalization (Cotter et al., 2015; Gould et al., 2009).

Among the most robust risk factors for suicide is a history of past suicide attempts (Forman, Berk, Henriques, Brown, & Beck, 2004; Miranda et al., 2008; Suominen et al., 2004). Past attempts outperform psychiatric disorders, including depression, as a predictor of future risk, with an attempt by any method shown to be associated with a 38-fold increase in suicide risk (Harris & Barraclough, 1997). A history of multiple suicide attempts (Rudd, Joiner, & Rajab, 1996) and/or violent or medically serious suicide attempts (Beautrais, 2003) also appear to be particularly potent indicators of risk.

Despite this knowledge, little is known about which methods most accurately assess suicide attempt history, and there is a striking lack of consensus across clinical practice guidelines in the field (Bernert, Hom, & Roberts, 2014). This is an important area of inquiry based on previous research indicating that differential reporting of psychiatric symptoms may occur depending on assessment type and format (Garb, 2007; Tourangeau & Yan, 2007; Turner et al., 1998). One prior study in this area found that when follow-up questions (e.g., “What was the reason for the incidence [sic]?” and “What kind of injuries did you have?”) were included in a self-report survey of attempt history (as an adjunct to asking “Have you ever attempted suicide?” and “How strong was the wish to die?”), the number of individuals identified as having a suicide attempt history decreased from 60 to 45 (Plöderl, Kralovec, Yazdi, & Fartacek, 2011). Another study compared differences in responses to self-report versus clinician-administered questions about past suicidal behaviors (Kaplan et al., 1994). The wording of questions was identical across the two assessments. Although no differences were observed in the reporting of past suicide attempts, individuals were more likely to endorse ideation on the self-report survey.

These findings suggest that various survey methods and formats may yield differential information regarding past suicidal ideation and behaviors; however, neither study specifically compared a single-item assessment of suicide attempt history—a format often used in epidemiological and other studies—to a multi-item survey with follow-up probes. Nor was this single-item assessment compared with a face-to-face interview assessment also allowing for additional follow-up questions. Thus, further work is needed to investigate how reporting of suicide attempt history might vary between assessment formats, especially given that there are various forms of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The wide range of the continuum of suicidal behaviors is exemplified in the CDC’s Uniform Definitions for Self-Directed Violence, which are as follows: (1) suicide attempt: a non-fatal self-directed potentially injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior; (2) interrupted suicide attempt: a person takes steps to injure self but is stopped by another person prior to fatal injury; (3) aborted suicide attempt: a person takes steps to injure self but is stopped prior to fatal injury; (4) suicidal ideation: thoughts of engaging in suicide-related behavior; and (5) non-suicidal self-injury: behavior that is self-directed and deliberately results in injury or potential injury to oneself, and there is no evidence, whether implicit/explicit of suicidal intent (Crosby, Ortega, & Melanson, 2011).

There is particular rationale to evaluate the assessment of attempt history among youths. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among college students, and youth attempt suicide at disproportionately higher rates relative to other age groups (i.e., 100 versus 25 attempts for every death by suicide; CDC, 2010; IOM, 2002; Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis, & Irwin, 2006). These findings, taken together with research indicating that suicide risk is heightened in the years immediately following an attempt (Christiansen & Jensen, 2007; Gibb, Beautrais, & Fergusson, 2005), indicate that accurate assessment of suicidal behaviors is especially salient to youth suicide prevention efforts. Because single-item attempt history screenings are commonly administered in university settings (e.g., to recruit participants for research studies), assessment considerations in this age group may be especially important clinically.

The Present Study

To date, a study has yet to evaluate how suicide attempt history reporting may vary by method of assessment among young adults. This study sought to compare the measurement of suicide attempt history by a single-item survey, multi-item survey with follow-up questions, and a semi-structured face-to-face clinical interview. The study used archival data from a research project recruiting young adults at high suicide risk (F31MH080480).

Methods

Participants

Participants were undergraduates (N = 100) selected for study inclusion based on endorsement of a suicide attempt history on a prescreening survey. Participants ranged in age from 17 to 24 (M = 19.1 years, SD = 1.4), and the sample was 67% female (n = 67) and 32% male (n = 32). The breakdown of self-identified race was as follows: 62% White, 19% Black, 10% Hispanic/Latino, 3% Asian/Pacific Islander, 4% Mixed Race, and 2% Other Race. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Measures

Screening Phase 1: Single-Item Prescreening Survey Assessment (Mass Screening Across Undergraduate Courses)

The prescreening survey was part of a battery of self-report questionnaires administered to undergraduates in an introductory psychology course. The survey included a single item inquiring about past history of suicide attempts (0, 1, 2, 3 or more attempts): “Have you ever attempted suicide, where you attempted to kill yourself?”

Screening Phase 2: Multi-Item Follow-Up Survey Assessment (In Laboratory)

This self-report assessment similarly asked individuals to either endorse or deny an attempt history; however, additional questions probing the nature of these suicide attempt(s) were also presented. These items were open-ended (i.e., a written free response) and included the following: “When did these attempt(s) occur? (Year/Mos),” “What was the method used for each attempt?” and “Did you require any medical treatment for these attempts?” This measure also captured demographic and medical history information.

Screening Phase 3: Face-to-Face Interview Assessment (In Laboratory)

An in-person, clinical prescreening interview was utilized to further assess and verify the timing, nature, and circumstances of past suicide attempts (i.e., originally endorsed by survey), along with most recently experienced (< 6 months) symptoms (i.e., any suicidal behaviors, non-suicidal self-injury, or suicidal ideation). If a suicide attempt was present, participants were asked to rate their desire for death at the time of the last suicide attempt (e.g., low, medium, high), as this is known to be associated with increased risk.

Procedures

This study was part of a larger investigation screening individuals at high risk for suicide based on suicide attempt history endorsement. Undergraduates (N = 4,847) completed Screening Phase 1, a prescreening survey, in an introductory psychology course at a large, public university as part of a screening for a department-wide research pool (2/9/2007 to 4/2/2008). Individuals were invited to participate in the current study if they endorsed a history of at least one previous suicide attempt. This was used as a proxy variable to screen for a high suicide risk target sample. Following written informed consent and study enrollment, participants (n = 100) completed a follow-up self-report survey as part of Screening Phase 2, followed by Screening Phase 3, which included a brief, face-to-face clinical interview. The interview was conducted by a project manager trained in a comprehensive data and safety monitoring protocol, including standardized suicide risk assessment procedures and use of clinical decision-tree rules for emergency referral (Joiner et al., 1999; Rudd, Joiner, & Rajab, 2001). Supervision was provided by a licensed clinician and on-call clinical coverage team. CDC uniform definitions for self-directed violence were applied to determine the absence or presence of suicidal behaviors for each screening phase. Determinations were based on a review of reported attempt methods and circumstances (e.g., evaluation of whether self-harm with intent to die was enacted or only considered). All procedures adhered to an internal departmental policy for emergency assessment, referral, and notification procedures, and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board as well as NIH’s Human Subjects Board.

Results

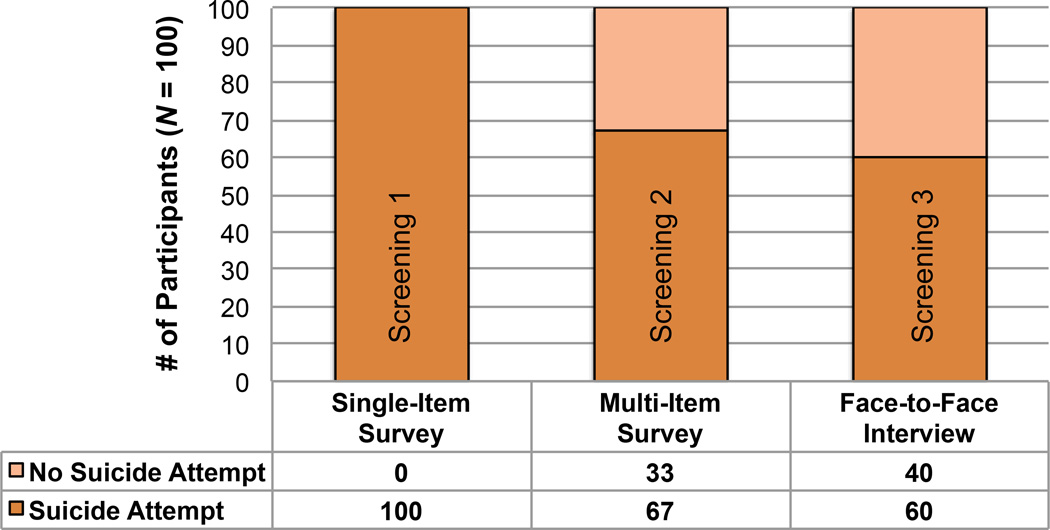

Since Screening Phases 1 and 2 did not afford an opportunity for individualized follow-up questions, participants could only be categorized as having or not having an attempt history. All participants (N = 100) positively endorsed at least one past suicide attempt at Screening Phase 1. At Screening Phase 2, 67% reported a past attempt and 33% reported no past attempts. This represented a significant decrease from Screening Phase 1 to Screening Phase 2 in the number of participants reporting a past attempt (χ2 [1] = 49.25, p < .001).

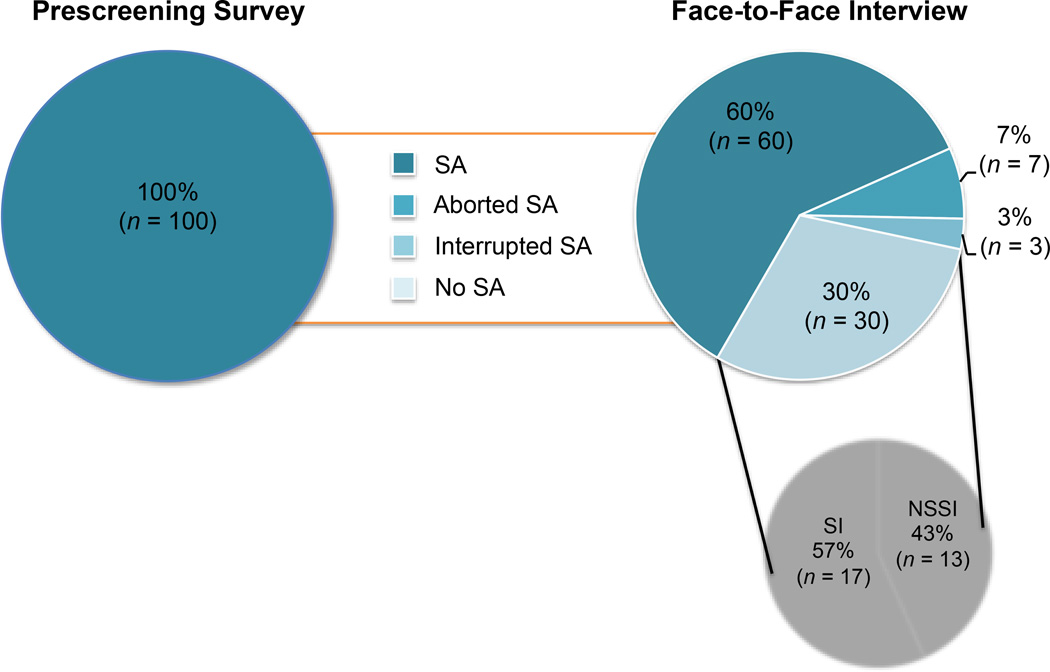

For Screening Phase 3, individuals were categorized based on the most severe form of suicidality endorsed, which, by increasing severity were: suicidal ideation, aborted/interrupted attempt, and suicide attempt. No individuals qualified for both an aborted and interrupted attempt, so distinctions in severity were not required for these behaviors. At Screening Phase 3, only 60% of participants qualified for a suicide attempt. Of these individuals, 70% reported a single suicide attempt history and 30% reported a multiple attempt history. For the 40% who reported a past suicide attempt on the prescreening survey but did not qualify for a suicide attempt in the interview, 3% qualified for an interrupted suicide attempt, 7% for an aborted suicide attempt, and 30% for no suicide attempt (see Figures 1 and 2). Among the 30% of individuals who endorsed a suicide attempt by survey but did not qualify for a suicide attempt based on face-to-face assessment, 43.3% instead reported a history of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; n = 13) and 56.7% only had history of past suicidal ideation (n = 17). Following face-to-face assessment, of the N = 100 participants, all (100%) reported a history of some form of suicide-related symptoms or behaviors (i.e., either a history of attempts, suicidal ideation, or NSSI). The proportion of participants reporting a suicide attempt during Screening Phase 2 and Screening Phase 3 did not differ significantly from one another (χ2 [1] = 2.22, p = .137).

Figure 1.

Participants Endorsing a History of Suicide Attempts Across Assessment Types

Note. Suicide attempts are defined utilizing the CDC’s uniform definitions for self-directed violence (Crosby et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Attempt Categorization Using CDC Uniform Definitions Following the Face-to-Face Interview

Note: SA = Suicide Attempt, SI = Suicidal Ideation, NSSI = Non-Suicidal Self-Injury; Due to the inability to ask follow-up questions at Screening Phases 1 and 2, it was not possible to obtain further detail regarding suicidal behavior type for these assessment time points.

Discussion

Our results primarily underscore the limitations of solely relying on a single-item, dichotomous response (i.e., Yes/No) assessment of suicide attempt history. Although it cannot be definitively determined which assessment type produced the most accurate information since responses were not compared against objective external criteria, the discrepancies between responses on the single-item versus multi-item measures suggest that validity of suicide attempt history information may be impacted by assessment type. All participants who denied an attempt history on the Screening Phase 2 multi-item survey—after initially endorsing an attempt history on the Screening Phase 1 single-item prescreening survey—instead appeared to qualify for history of serious thoughts of suicide or NSSI. Thus, it seems that the additional follow-up questions enhanced participants’ and researchers’ abilities to make distinctions between suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, and NSSI. This suggests that a single-item self-report assessment of suicide attempt history, especially without accompaniment by standardized definitions, may challenge individuals’ classifications of their prior suicidal behaviors. Of note, the clinical interview did not yield attempt history information that was significantly different from that obtained on the multi-item survey, indicating that a face-to-face assessment may not provide incremental information to a self-report measure.

The potential impact of differential reporting of suicide attempts on referrals and intervention opportunities raises ethical and legal concerns regarding the assessment and management of suicide risk since inappropriate care may be provided as a result (e.g., inaccurate categorization as a multiple attempter may result in more severe clinical action than warranted; Bernert & Roberts, 2012; Bryan & Rudd, 2006). In addition, such findings have implications for epidemiological studies, which commonly rely on a self-reported, single-item assessment of suicide attempt history. According to our results, such surveys may benefit from revision to include multiple questions or answer options, as well as use and provision of well-defined uniform definitions (e.g., those published by the CDC; Crosby et al., 2011). It may also be advantageous for clinicians to routinely incorporate follow-up questions when an individual endorses a suicide attempt history in a face-to-face assessment (e.g., to distinguish a history of plans and preparations for suicide from a suicide attempt history). This is consistent with research emphasizing the utility of supplementing self-report measures of psychopathology with clinician assessment, particularly as a means by which to enhance accuracy of symptom information (Garb, 2007).

Despite the above considerations, the present findings also emphasize the utility of a single-item self-report measure as a large-scale screening method. For example, positive endorsement of such an item, specifically when current suicidal thoughts are also reported, can signal to clinicians that an individual may be at elevated risk for suicide and that a more extensive follow-up assessment is warranted (Chu et al., 2015; Joiner et al., 1999). Single-item attempt history screening questions are also useful in identifying potentially eligible research participants, as evident in our own study. Though not all individuals who positively endorsed a suicide attempt history on the single-item screener ultimately appeared to have an attempt history based on the multi-item survey, the remainder of individuals instead qualified for a history of suicidal ideation and NSSI, which are known suicide risk factors (Nock et al., 2008; Victor & Klonsky, 2014). This suggests that a single item may enhance detection of high suicide risk individuals across settings and crucially inform the classification of suicidal behaviors.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are a number of limitations in the present study. Although the sample included a relatively large number of individuals belonging to a high-risk demographic group, data were only collected at a single institution. Replication across multiple settings and samples is thus warranted. Further, assessment of systematic differences between participants and those who endorsed an attempt history but did not elect to participate in the present study was not possible in the current investigation. This might be fruitful to explore in future studies. Lastly, individuals were not explicitly asked why they endorsed a suicide attempt history on the prescreening survey, but later denied an attempt on the follow-up questionnaire. It is possible that the sense of anonymity provided by a mass screening setting, relative to that occurring in person, may have resulted in greater endorsement of suicidal behaviors. Studies designed to assess the underlying reasons or other influential factors (e.g., survey setting) for reporting differences may inform improvements in the assessment of attempt history.

Additional research is also warranted to extend the present findings by systematically comparing attempt history information obtained from self-report and clinician-administered versions of the same standardized questionnaire. Although semi-structured interviews may afford clinicians the flexibility to ask clarifying questions, evidence suggests that individuals may be more open to disclosing information regarding suicidality (Glassmire, Stolberg, Greene, & Bongar, 2001) and other psychiatric symptoms (Garb, 2007; Tourangeau & Yan, 2007; Turner et al., 1998) on self-report or computer-based measures. Therefore, results from this type of study would be particularly illuminating. These investigations would be further bolstered by inclusion of external criteria (e.g., medical records, family/friend report) against which self-report and interview-assessed attempt history information could be compared. Finally, it would be useful to compare self-reported and clinician-assessed attempt histories when detailed definitions regarding what constitutes a suicide attempt are provided to individuals (e.g., CDC uniform definitions). This may assist in pinpointing whether differential reporting may be a result of confusion regarding nomenclature or a preference for a certain disclosure format. We look forward to these and other future studies evaluating the most accurate methods by which to obtain a suicide attempt history since this knowledge will aid our suicide research, intervention, and prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the following grant funding: National Institutes of Health (F31MH080480, K23MH093490) and the Military Suicide Research Consortium, an effort supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs under Award No. (W81XWH-10-2-0181). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Military Suicide Research Consortium or the Department of Defense.

References

- Beautrais AL. Subsequent mortality in medically serious suicide attempts: a 5 year follow-up. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37(5):595–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert RA, Hom MA, Roberts LW. A review of multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines in suicide prevention: toward an emerging standard in suicide risk assessment and management, training and practice. Academic Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):585–592. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert RA, Roberts LW. Ethical considerations in suicide risk assessment and management. Focus. 2012;10:467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(2):185–200. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] WISQARS: Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars/default.htm.

- Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: a register-based survival analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(3):257–265. doi: 10.1080/00048670601172749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Klein KM, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE. Routinized assessment of suicide risk in clinical practice: An empirically informed update. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jclp.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter P, Kaess M, Corcoran P, Parzer P, Brunner R, Keeley H, Wasserman D. Help-seeking behaviour following school-based screening for current suicidality among European adolescents. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby AE, Ortega L, Melanson C. Self-Directed Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Berk MS, Henriques GR, Brown GK, Beck AT. History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):437–443. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garb HN. Computer-administered interviews and rating scales. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(1):4–13. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb SJ, Beautrais AL, Fergusson DM. Mortality and further suicidal behaviour after an index suicide attempt: a 10-year study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(1 – 2):95–100. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassmire DM, Stolberg RA, Greene RL, Bongar B. The utility of MMPI-2 suicide items for assessing suicidal potential: Development of a Suicidal Potential Scale. Assessment. 2001;8(3):281–290. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Hoagwood K, Kleinman M, Amakawa L, Altschuler E. Service use by at-risk youths after school-based suicide screening. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(12):1193–1201. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bef6d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–228. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Reducing suicide: A national imperative. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Walker RL, Rudd DM, Jobes DA, Joiner TE, Jr, Walker RL, Jobes DA. Scientizing and routinizing the assessment of suicidality in outpatient practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1999;30(5):447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M, Asnis G, Sanderson W, Keswani L, De Lecuona J, Joseph S. Suicide assessment: Clinical interview vs. self-report. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1994;50(2):294–298. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199403)50:2<294::aid-jclp2270500224>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Scott M, Hicks R, Wilcox HC, Harris Munfakh JL, Shaffer D. Suicide attempt characteristics, diagnoses, and future attempts: comparing multiple attempters to single attempters and ideators. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Williams D. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(3):309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MJ, Mulye TP, Adams SH, Brindis CD, Irwin CE. The health status of young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(3):305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M, Kralovec K, Yazdi K, Fartacek R. A closer look at self-reported suicide attempts: false positives and false negatives. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2011;41(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Joiner TE, Rajab H. Treating Suicidal Behavior: An Effective Time-Limited Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Joiner T, Rajab MH. Relationships among suicide ideators, attempters, and multiple attempters in a young-adult sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(4):541–550. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suominen K, Isometsä E, Suokas J, Haukka J, Achte K, Lönnqvist J. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):562–563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(5):859–883. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein F. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280(5365):859–883. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Correlates of suicide attempts among self-injurers: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(4):282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Geneva: WHO Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]