Abstract

Hirschprung’s disease (HD), a very common congenital abnormality in children, occurs mainly due to the congenital developmental defect of the enteric nervous system. The absence of enteric ganglia from the distal gut due to deletion in gut colonization by neural crest progenitor cells may lead to HD. The capacity to identify and isolate the enteric neuronal precursor cells from developing and mature tissues would enable the development of cell replacement therapies for HD. However, a mature method to culture these cells is a challenge. The present study aimed to propose a method to culture enteric neural stem cells (ENSCs) from the DsRed transgenic fetal rat gut. The culture medium used contained 15 % chicken embryo extract, basic fibroblast growth factor, and epidermal growth factor. ENSCs were cultured from embryonic day 18 in DsRed transgenic rat. Under inverted microscope and fluorescence staining, ENSCs proliferated to form small cell clusters on the second day of culture. The neurospheres-like structure were suspended in the medium, and there were some filaments between the adherent cells from day 3 to day 6 of the culture. The neurospheres were formed by ENSCs on day 8 of the culture. Network-like connections were formed between the adherent cells and differentiated cells after adding 10 % FBS. The differentiated cells were positive for neurofilament and glial fibrillary acidic protein antibodies. The present study established a method to isolate and culture ENSCs from E18 DsRed transgenic rats in the terminal stage of embryonic development. This study would offer a way to obtain plenty of cells for the future research on the transplantation of HD.

Keywords: ENSCs, CEE, Neurospheres, Cell culture

Introduction

Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) is one of the most common congenital gastrointestinal abnormalities in children. It occurs mainly due to the congenital developmental defect of the enteric nervous system (ENS). HD occurs in about one in 5,000 children, and the clinical symptoms included abdominal distension, delayed passage of meconium, and intractable constipation (Furness 2008). The reason for the cause of HD is mainly the interruption of the migration of ectodermal neural crest cells during development, which results in the deficiency of ganglionic cells in the myenteric nerve plexus on distal segment of the intestinal wall (Kapur 1999). Currently, the therapies of HD include the resection and reanastomosis of the intestinal canal. Although the therapy method of HD has greatly been improved over the years, the incidence rate of postoperative complications remains high (20–40 %). There is no effective therapy identified which concentrates the entire colon of the children with HD (Kenny et al. 2012; Metzger 2011). The previous studies showed that the embryonic stem cell (ESC) and central nervous system-neural stem cell (CNS-NSC) could be differentiated into neurons and glial cells (Kawaguchi et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2007). Scientists are currently involved in the endeavor to transplant the enteric neural stem cells (ENSCs) into the lesion gut, which could rebuild nervous system and radically cure the HD; and they have achieved preliminary effects (Marco Metzger et al. 2009a, b; Hotta et al. 2011; Joseph et al. 2011). However, the transplanted ENSCs were not successful in rebuilding the nervous system of the gut. It is also a challenge to get sufficient ENSCs stably to achieve successful ENSCs transplantation. Therefore, the standardization of a mature culture method for ENSCs is very essential for the successful cell replacement therapy of HD. The previous in vitro studies were able to isolate ENSCs from mice and human bodies. These cells can proliferate and differentiate into various subtypes of neurons and glial cells (Kruger et al. 2002; Bondurand et al. 2003; Lindley et al. 2008; Marco Metzger et al. 2009a, b). However, the success of ENSC transplantation therapy depends on various parameters like quantity of ENSCs, immunological rejection after transplantation, transplant environment such as endothelin 3, differentiation of intestinal wall, and even the protein expressed by the smooth muscle of patients with HD (Tam and Garcia-Barcel. 2009; Druckenbrod and Epstein 2009; Hotta et al. 2010; Hagl et al. 2012). Kruger et al showed that the amount of ENSCs was lesser when obtained from the gut of a 15-day-old rat (Kruger et al. 2002). Unlike ESCs and CNS-NSCs which can achieve a sufficient number for in vitro culture (Schafer et al. 2009), it is difficult to obtain enough number of ENSCs. It is because that the number of ENSCs in the gut is small and ENSCs are hard to obtain and culture in vitro. Moreover, during transplantation, the cultured ENSCs usually need to be fluorescently labelled and transfected with guiding plasmid deoxy ribonucleic acid; but the fluorescence labeling often gets eliminated after cell proliferation, then the tracing becomes very difficult. Thus, a mature method of ENSCs culture should be explored further. The present study provides a convenient cell culture technique of enteric neural stem cell, which could lay a solid foundation for the therapy of congenital developmental defect type disease in ENS.

Materials and methods

Culture medium and reagents

Enteric neural stem cells (ENSCs) were incubated in serum-free medium consisting of equal volumes of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium low glucose (DMEM-Low) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with the addition of 1 % nitrogen supplement (Invitrogen), 2 % B27 supplement (Invitrogen), 35 ng/mL retinoic acid ([RA] Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 50 μM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Sigma), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (Sigma), 15 % Chicken Embryo Extract ([CEE], Absin China), and 2 % benzylpenicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). The differentiation culture medium was DMEM-Low medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum [(FBS), Sigma]. Mouse anti-Nestin antibody (Invitrogen), rabbit anti-neurofilament antibody ([NF], Invitrogen), and rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody ([GFAP], Invitrogen), and secondary antibodies labeled with alexa fluorescence 488 (goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) and goat anti-rabbit IgG, Invitrogen, USA) were used for immunofluorescence.

Isolation and cultivation of ENSCs

ENSCs were cultured from embryonic day-18 DsRed transgenic rats, which were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Nantong University of China. Each part of the DsRed transgenic rats can be seen via the red fluoresence. All animal dissections were conducted under the Institutional Animal Care guidelines and approved ethically by the Administration Committee of Experimental Animals, Nantong University of China. The rat was anesthetized and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The uteri were removed and stored in the commercial medium DMEM which was supplemented with antibiotics (2 %) as dissection buffer on ice, and one litter rats (8–12 pups) was dissected subsequently. After collecting all embryos, the gastrointestinal tracts were removed by manual dissection and cut into pieces (about 0.5–1 mm3) by microsurgical instruments. These pieces were digested by collagenase (Sigma) about 30 min. After that, we used a 400 mesh to catch impurities and then centrifugation (800–1,000 r/min, 5 min) was used to collect cells. The dissection was done within 1 h to avoid a prolonged processing time and loss of surviving precursor cells. The collected cells were plated in culture dishes using the serum-free culture medium. The cells were then grown in culture for various periods of time at 37 °C with 5 % carbon dioxide. About 50 % of the medium was changed every other day from the day of plating. After incubation for 5–9 days, cells were proliferated to form neurospheres and were ready for subculture.

Passaging neurospheres at different time point for primary culture

Cells were proliferated to form spheroids, called neurospheres, and detached from the plastic substrate and floated in suspension. Passaging was carried out on day 8 or 9. The neurospheres were washed in phosphate buffered saline and incubated in 0.25 % trypsin (Sigma) for 2–3 min at 37 °C and dissociated mechanically into a single cell suspension, which was cultured in two groups. One group was cultured with serum-free ENSCs medium, and the other one was cultured with ENSCs medium containing serum. The cells were collected and reseeded in new culture flasks with the same centrifugation conditions and density used during the primary culture.

Identification of ENSCs

At different time points, cells were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Cells were preblocked in blocking solution (3 % bovine serum albumin, 10 % normal goat serum, and 0.3 % Triton-X 100 Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody incubations were held overnight at 4 °C; and secondary incubations with anti-mouse, anti-goat, or anti-rabbit antibodies were performed for 2 h at room temperature. The primary antibodies and concentration used were as follows: nestin (1:200), NF (1:200), and GFAP (1:200). All fluorescent cell stainings were viewed under a fluorescent microscope (Leica, Germany).

Results

Morphology of cells

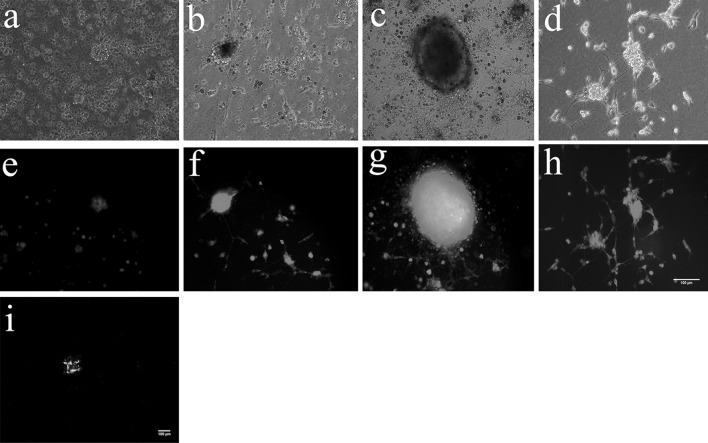

On the first day of cultivation, cell adhesion was noticed in the form of a spindle and also with other different forms, surrounded with some cell debris. On the second day, cells were grown into small cell cluster. The cell clusters were seen under the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 1a). From day 3 to 6, cells grown into suspended neurosphere-like bodies, which are above the adherent cells and connected with long filamentary protrusions (Fig. 1c). On day 8, ENSCs propagated into suspended neural spheres (Fig. 1e). Cell differentiation happened after adding 10 % serum, and a network-like structure was formed with surrounding differentiated cells and adherent cells (Fig. 1g). The neural spheres cells were digested by trypsin and the cells were subcultivated, which grew into new neural spheres.

Fig. 1.

The morphological features of neurospheres at different stages in culture. a, e Enteric neural stem cells proliferated to form small cell clusters on the second day of culture. b, f The neurosphere-like bodies were suspended in the medium. There were some filaments between the adherent cells from day 3 to day 6 of the culture. c, g The neurospheres were formed by enteric neural stem cells on day 8 of the culture. d, h Network-like connections were formed between the adherent cells and differentiated cells. i The neurosphere was nestin positive. a–d were obtained using an inverted microscope; Because these cells fluoresce in red, images in panels e–h were obtained using a fluorescence microscope. Scale bars 100 μm for all panels

Immunostaining of cells

Nestin, which is also called nidogen, could signify that some molecular markers in neuroepithelial stem cells might have an effect on the differentiation of neurons. It is expressed in the early stage of embryonic development. It is considered as the characteristic marker of neural stem cells. The result of immunology experiment showed that the obtained cells were nestin-positive (Fig. 1i), indicating that these cells were in stem cell stage. NF and GFAP are the characteristic markers of mature neurons and glial cells. After the differentiation of these cells, they were GFAP- and NF-positive (Fig. 2). This suggested that these cells can differentiate into neurons and glial cells. Controls were all negative.

Fig. 2.

The differentiation of entric neural stem cells a The differentiated cells were GFAP-positive (green). d The differentiated cells showed NF-positive (green). b, e Representative immunostaining with Hoechst 33342 counterstain (blue). c, f Recpresentative immunostaining with Hoechst 33342 counterstain (blue) and NF and GFAP (green) antibodies for differentiated ENSCs. g Differentiation rate of neurospheres. Scale bars 100 μm for all panels. (Color figure online)

Discussion

In this study, we established a stable and convenient method to isolate and culture ENSCs on the basis of previous studies (Le et al. 2004; Farlie et al. 2004; Ulrich Rauch et al. 2006). We found out that the numbers of ENSCs obtained from the adult and new born mice were very low. The proliferation capacity and neurosphere quantity of ENSCs from the adult and new born mice were not good when compared with the same from DsRed transgenic fetal rats. Hence, the DsRed transgenic fetal rats were concluded as the right specimen for the current study. The composition of culture medium was one of the critical factors for the successful culture of ENSCs. Based on the previous studies (Almond et al. 2007; Lindley et al. 2008, 2009), we succeeded in culturing ENSCs. The culture medium (DMEM (low glucose), RA, N2, B27 and 2-Mercaptoethanol) which contains CEE, bFGF, EGF was helpful in proliferating and growing the obtained cells into suspended neurospheres. Furthermore, this culture medium is only suitable for stem cells. So we can use this characteristic to isolate ENSCs by continuous passage. Later, 10 % FBS was added to the medium and served as the differentiation medium. The neurospheres were differentiated into NF-positive neurons and GFAP-positive glial cells. After differentiation, the long processes of cells formed complex network-like structure, which may develop into the plexus structure later (Fig. 1g, h). During subculture, we found that the time of digestion was different from other types of cells. Because the time of digestion affects the ability of cell proliferation, so the right time was 2–3 min.

The present study established a stable method to culture ENSCs and obtain neurospheres in sufficient quantity. The cells we obtained were Nestin-, NF- and GFAP-positive, which indicated that these cells possessed features of self-renewal, proliferation and multi-differentiation potential. This approach could helped to resolve the long-standing problems of ESC shortage and would also established a solid foundation for therapies of congenital defective ENS diseases by ENSCs replacement therapy. In this study, we obtained the improvement and modifications for ENSCs culture as followings. Firstly, we obtained ENSCs from the embryonic day-E18 DsRed transgenic rat pups as cell source, although the E18 was in the terminal stage of embryonic development and the number of ENSCs was very limit. Secondly, we used rats as the animal model. Because rats are bigger than mice, they are very helpful to establish the HD model and perform therapies of HD by transplanting ENSCs. Additionally, we cultured ENSCs from E18 DsRed transgenic rat. It would be very convenient to trace the fate of transplanted ENSCs since they all naturally fluoresce in red.

In conclusion, the present study established a method to isolate and culture ENSCs from the embryonic day-E18 DsRed transgenic rat pups in the terminal stage of embryonic development. The previous studies (Lindley et al. 2009) had indicated that the ENSCs from human enteric nervous systerm were considered as a cell source of the transplantation of HD. This study would offer a way to obtain plenty of human ENSCs for the future research on the transplantation of HD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the social undertakings technological innovation and demonstration project foundation of Nantong City (No. HS2012026) and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China.

Contributor Information

Wenliang Ge, Phone: 13962854122, Email: gwl1618@sina.com.

Qiyou Yin, Phone: 13861994898, Email: yinqiyou@aliyun.com.

References

- Almond S, Lindley RM, Kenny SE, Connell MG, Edgar DH (2007) Characterisation and transplantation of enteric nervous system progenitor cells. Gut 56:489–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bondurand N, Natarajan D, Thapar N, Chris Atkins C, Pachnis V (2003) Neuron and glia generating progenitors of the mammalian enteric nervous system isolated from fetal and postnatal gut cultures. Development 130:6387–6400 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Druckenbrod NR, Epstein ML. Age-dependent changes in the gut environment restrict the invasion of the hindgut by enteric neural progenitors. Development. 2009;136:2195–2303. doi: 10.1242/dev.031302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlie PG, McKeown SJ, Newgreen DF. The neural crest: basic biology and clinical relationships in the craniofacial and enteric nervous systems. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today. 2004;72:173–189. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness JB (2008) The enteric nervous system normal functions and enteric neuropathies. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20:32–38.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01094.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hagl CI, Heumüller S, Klotz M, Subotic U, Wessel L, Schäfer KH (2012) Smooth muscle proteins from Hirschsprung’s disease stem cell differentiation. Pediatr Surg Int 28:135–142. doi:10.1007/s00383-011-3010-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hotta R, Anderson RB, Kobayashi K, Newgreen DF, Young HM (2010) Effects of tissue age, presence of neurons and endothelia-3 on the ability of enteric neuron precursors to colonize recipient gut:implications for cell-based therapies. Neurogastroenterol Motil 22:331–386. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01411.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hotta R, Natarajan D, Burns AJ, Thapar N. Stem cells for GI motility disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph NM, He S, Quintana E, Kim Y-G, Núñez G, Morrison SJ (2011) Enteric glia are multipotent in culture but primarily form glia in the adult rodent gut. J Clin Invest 121:3386–3389. doi:10.1172/JCI58186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kapur RP. Hirschsprung disease and other enteric dysganglionoses. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1999;36:225–273. doi: 10.1080/10408369991239204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi J, Nichois J, Gierl MS, Faial T, Smith A (2012) Isolation and propagation of enteric neural crest progenitor cells from mouse embryonic stem cells and embryos. Development 137:693–704. doi:10.1242/dev.046896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kenny SE, Tam PKH, Garcia-Barcelo MM (2012) Hirschsprung’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg 19:73–83. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kruger GM, Mosher JT, Bixby S, Joseph N, Iwashita T, Morrison SJ (2002) Neural crest stem cells persist in the adult gut but undergo changes in self-renewal, neuronal subtype potential and factor responsiveness. Neuron 35:657–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Le Douarin NM, Creuzet S, Couly G, Dupin E (2004) Neural crest cell plasticity and its limits. Development 131:4637–4650 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindley RM, Hawcutt DB, Connell MG, Almond SN, Vannucchi M-G, Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Edgar DH, Kenny SE (2008) Human and and mouse enteric nervous system neurosphere transplants regulate the function of aganglionic embryonic distal colon. Gastroenterology 135:205–216. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindley RM, Hawcutt DB, Connell MG, Edgar DH, Kenny SE (2009) Properties of secondary and tertiary human enteric nervous system neurospheres. J Pediatr Surg 44:1249–1255. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu W, Wu RD, Dong YL, Gao, YM (2007) Neuroepithelial stem cells differentiate into neuronal phenotypes and improve intestinal motility recovery after transplantation in the aganglionic colon of the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19:1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marco Metzger M, Bareiss PM, Danker T, Wagner S, Hennenlotter J, Guenther E, Obermayr F, Stenzl A, Koenigsrainer A, Skutella T, Just L (2009a) Expansion and differentiation of neural progenitors derived from the human adult enteric nervous system. Gastroenterology 137:2063–2073. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marco Metzger M, Caldwell C, Barlow AJ, Burns AJ, Thapar N (2009b) Enteric nervous system stem cells derived from human gut mucosa for the treatment of aganglionic gut disorders. Gastroenterology 136:2214–2225. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Metzger M (2011) Neurogenesis in the enteric nervous system. Arch Ital Biol 148:73–83 [PubMed]

- Schafer KH, Micci MA, Pasricha PJ. Neural stem cell transplantation in the enteric nervous system: roadmaps and roadblocks. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:103–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam PK, Garcia-Barcel M. Genetic basis of Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:543–558. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich Rauch U, Hänsgen A, Hagl C, Holland-Cunz S, Schäfer K-H (2006) Isolation and cultivation of neuronal precursor cells from the developing human enteric nervous system as a tool for cell therapy in dysganglionosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 21:554–559 [DOI] [PubMed]