Abstract

Introduction

Recent advances in treatment have led to the prolongation of life among patients with prostate cancer (PCa), which implies greater interest in the issue of the quality of life (QoL) in patients who undergo treatment. The quality of life of patients with cancer questionnaire (QLQ-C30) and the quality of life questionnaire specific to PCa (QLQ-PR25) are tools used worldwide to conduct research on this subject. In our study we assessed the quality of life in a population of Polish patients suffering from prostate cancer. Differences in the quality of life depending on the stage of the disease were highlighted.

Material and methods

We conducted a prospective, multicenter, observational study using the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 questionnaires in a group of 1047 patients.

Results

The highest QoL scores (according to the QLQ-C30 questionnaire) were observed in patients with localized prostate cancer, while the lowest were recorded in the metastatic group. Sexual activity and sexual functioning assessed on the basis of QLQ-PR25 was best in the group of patients suffering from localized prostate cancer, and the worst in patients with locally advanced PCa.

Conclusions

The assessment of QoL showed a significant correlation with the stage of the disease. Sexual activity and sexual functioning were the best in patients with localized cancer; worst among patients with locally advanced tumor.

Keywords: prostate cancer, quality of life, QLQ-C30, QLQ-PR25

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is a major health problem in the male population both in Poland and Europe. In 2012, with the number of new cases in Europe up to 416,730 (representing 22.8% of all cancer cases in male population), PCa placed first in terms of highest incidence of malignancy in men. Ferlay et al. estimated the number of new PCa cases in Poland to have reached about 11,030 [1]. The awareness of suffering from prostate cancer (PCa) is associated with poor psychological tolerance [2]. Systematic progress in medicine, advances in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, accompanied by an increase in life expectancy in the male population has lead to a growing number of patients with PCa – newly diagnosed, currently treated or after therapy.

Tools allowing for objective evaluation of patients’ QoL, enabling tracking its changes during the course of the disease, as well as assessing the impact of different types of therapies on QoL are encapsulated by the EORTC questionnaires – the quality of life in patients with cancer (QLQ-C30) and quality of life specific to PCa (QLQ-PR25). The former concerns the functional aspects of health related quality of life (HRQOL) and frequently occurring symptoms in cancer patients. The latter consists of multiple parts, assessing symptoms from the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, sexual functions, and adverse effects of treatment. Both were widely tested, and are regarded as reliable instruments in the quality of life measurement [3–6].

The aim of this study was to assess the quality of life in a population of Polish patients suffering from prostate cancer, stratified according to the stage of the disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This prospective, multicenter, observational study comprised 1080 patients, of whom 1047 (96.9%) completed the study. The research project received approval from the local ethics committee. According to our inclusion criteria we enrolled men over the age of 40, with diagnosed prostate cancer, who were able to read Polish and gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The presence of other cancer was an exclusion criterium. 108 physicians, providing outpatient practice all around Poland were involved in the study, education, and data collection from the patients. Patients were divided into 3 groups according to the stage of the disease: localized, locally advanced and metastatic PCa. Patients’ QoL was assessed using the EORTC questionnaire QLQ-C30 comprised of 5 scales, which assess functional status (physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning), three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain), and further, an overall assessment of the patient's medical condition/quality of life. Furthermore, the questionnaire evaluates six individual symptoms such as dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties as a consequence of the disease were evaluated. The second questionnaire (QLQ-PR25) assesses the quality of life specific to PCa. It assesses symptoms from the urinary and gastrointestinal tract, sexual function, and adverse effects of treatment. The raw scores of both questionnaires were linearly transformed into a 0–100 points scale. A high score on the functional scale represents a high/healthy level of functioning; a higher score on symptom scales shows higher symptom expression/lower health level [7]. A difference of 5–10 points in the scores represents small change, 10–20 points – moderate change and greater than 20 points – large, clinically significant change from the patient's perspective [8].

The examination procedure consisted of patients filling out QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 questionnaires, implementation of an educational program during the first visit, and afterwards re-evaluation of the quality of life based on the previously mentioned questionnaires after a period of three months. The total duration of the study was approximately 15 months.

RESULTS

The proportion of patients from the study group according to stage of disease:

Localized prostate cancer 377 (34.9%)

Locally advanced 516 (47.8%)

Metastatic disease 187 (17.3%) patients.

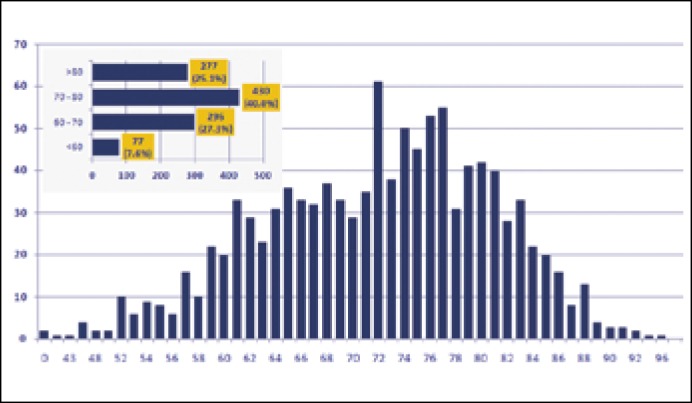

The proportion of patients with prostate cancer by decades of life:

<60 years of age 77 (7.6%)

60–70 years 296 (27.3%)

70–80 years 430 (40%)

>80 years of age 271 (25.1%) patients (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Age distribution in PCa patients.

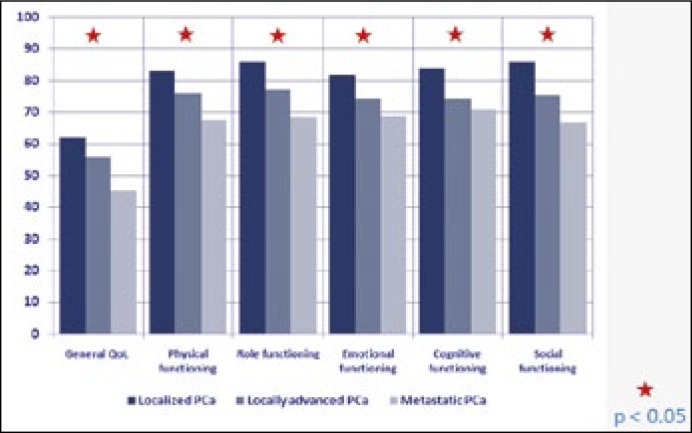

The highest QoL scores (62 points) were observed in patients with localized prostate cancer, while the lowest were recorded in the metastatic group (45 points). In locally advanced cancer general QoL was assessed as 56 points, placing it between the two other stages of PCa. Physical, emotional, cognitive and social functioning, as well as functioning in roles, evaluated using QLQ-C30, exceeded 80 points for patients with localized cancer and was lower than 70 points in patients with metastatic disease (p <0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

QLQ-C30 in the progress of the disease.

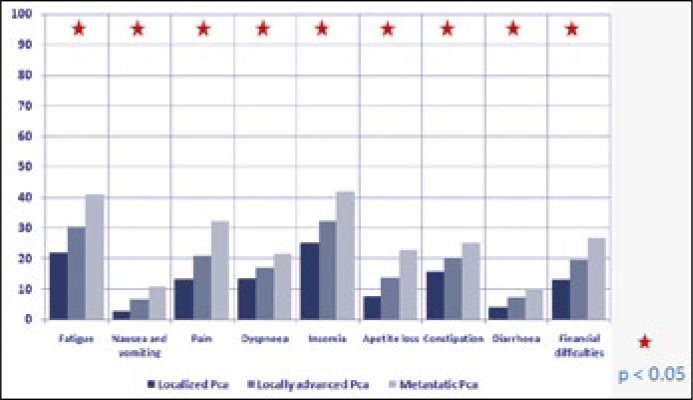

Fatigue, nausea, pain, shortness of breath, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhoea as well as financial problems were more frequent in patients with metastatic disease than in those with organ-confined disease (p <0.05) (Figure 3). Assessment of QoL, and physical, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning showed a statistically significant correlation with the stage of the disease (p <0.05).

Figure 3.

QLQ-C30 symptoms scale depending on the stage of the disease.

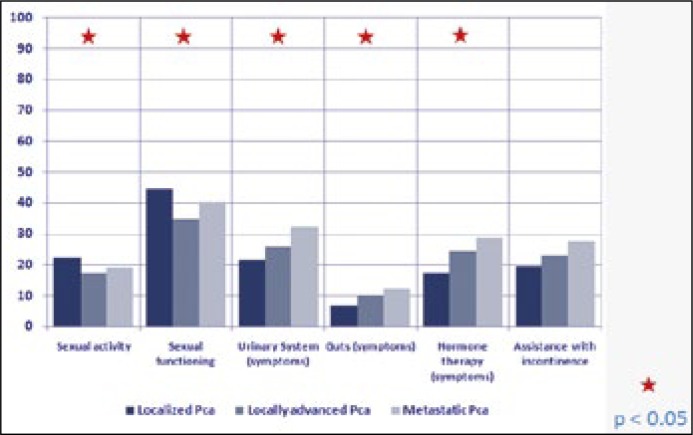

According to the QLQ-PR25, urinary and gastrointestinal tract symptoms, as well as side effects associated with hormone therapy, intensified with increasing tumour stage. Patients with localized cancer scored 22 on the urinary tract symptom scale, 7 on the gastrointestinal tract symptom scale and 17 points for adverse symptoms associated with androgen deprivation therapy. Among those with locally advanced disease, point scores reached 26, 10 and 24 respectively were recorded, whereas patients suffering from generalized PCa had the worst outcomes with 32, 12 and 29 points respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

QLQ-PR25 in the progress of the disease.

Level of sexual activity and sexual functioning were scored highest by patients with cancer localized to prostate, 22 and 44 points respectively. The worst QoL was reported by patients with locally advanced PCa, 17 and 35 points respectively. Accordingly, metastatic disease placed in between with 19 and 40 points respectively (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Ours is by far the largest population-based study evaluating the quality of life among Polish patients with prostate cancer. Previously published data confirmed the credibility of the questionnaires EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 in terms of reliability and validity, and confirmed their role as an accurate research tool used in the assessment of the quality of life [9]. While no differences might have been seen in general HRQOL disease-targeted measures (sexual, urinary, bowel domains) may differ significantly [10].

According to a prior survey by J. Dobruch et al., PCa was most often diagnosed in the group of patients aged 70–79 years. Our observations confirm the outcomes of their survey [11].

Prostate cancer is largely diagnosed at the early stages [12]. Furthermore, a significant number of detected cases of PCa will not progress to clinically significant cancer [13]. The specificity of PCa, as compared to other neoplasms, requires individualized approach. The urologists need to focus their therapeutic effects not only on the absolute prolongation of their patients’ life, but also on simultaneous achievement of the best possible quality of life [14]. Efforts must focus on minimizing the psychological distress, in order to prevent a decrease in the quality of life in patients undergoing treatment. The treatment of prostate cancer reduces the assessed QoL in all six scales of the QLQ-PR 25 questionnaire [15]. The best QoL is observed among patients undergoing active surveillance, while patients treated with chemotherapy evaluated their quality of life as being the lowest [16]. Taking into consideration the side effects of localized PCa treatment, radiotherapy seems to be at least as good a therapeutic option as radical prostatectomy [17].

Similarly to Braun et al., in our study group fatigue was one of most frequently reported symptoms in PCa patients [14]. The results of our observations coincide with those conducted by Vanagas et al. who analysed a group of 501 patients with prostate cancer. The highest QoL was found to be in cancer stage I according to NCI classification (from 72.2 on the social functioning scale to 88.9 in role functioning). The lowest results on the functioning scales were observed among patients with stage IV cancer (from 61.2 in emotional functioning to 72.7 in social functioning) [16]. In our study, the differences in the quality of life between localized and metastatic PCa ranged between 10 and 20 pts, which according to the results of Osoba, indicates a moderate impact on the quality of life [8, 18].

The evaluation of sexual activity in patients suffering from PCa on the basis of QLQ-PR25 revealed that the best results are in patients with localized cancer followed by patients with metastatic disease. The worst symptoms were reported by patients with locally advanced cancer. This situation may be explained by the more aggressive therapeutic procedures introduced during the process of radical treatment (radical prostatectomy without nerve-bundle preservation, radiotherapy) in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer, compared to those suffering from cancer localized to the organ. Such therapy decreases the likelihood of regaining sufficient erection for sexual intercourse. A greater chance of positive margins occurrence and local recurrence of the disease in locally advanced cancer compared to localized PCa requires the use of complementary therapies. This in turn leads to the accumulation of side effects and complications associated with implemented therapeutic methods. The hormone therapy applied in metastatic cancer has less impact on the quality of patient's sex life in comparison with the treatment carried out in locally advanced cancer.

CONCLUSIONS

The assessment of the quality of life, physical, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning showed a statistically significant correlation with the stage of the disease. The highest QoL, as assessed with the QLQ-C30, was reported by patients with localized prostate cancer, while the lowest scores were observed in the metastatic group. Sexual activity and sexual functioning were scored highest by patients with localized cancer, with the lowest scores reported among patients with locally advanced tumor.

The knowledge of changes in QoL in patients with prostate cancer can help to inform choice of therapy, and thus lead to greater acceptance of side effects and optimization of the patient-doctor relation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was designed and carried out under the auspices of the Polish Association of Urology and sponsored by IPSEN Poland.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. European Association of Urology 2015. http://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/

- 3.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groenvold M, Klee MC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK. Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient-observer agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hjermstad MJ, Fossa SD, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Test/retest study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1249–1254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu D, Popovic M, Chow E, et al. Development, characteristics and validity of the EORTC QLQ-PR25 and the FACT-P for assessment of quality of life in prostate cancer patients. J Comparat Effect Res. 2014;3:523–531. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta D, Braun DP, Staren ED. Staren. Prognostic value of changes in quality of life scores in prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2013;13:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osoba D. Interpreting the meaningfulness of changes in health-related quality of life scores: Lessons from studies in adults. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;83:132–137. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<132::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sosnowski M, Wolski Z, Jabłonowski Z, et al. Validity of EORTC, QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 questionnaires in assessing the quality of life of Polish patients with prostate cancer [article written in Polish] Przeg Urol. 2015;87:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes in men treated for localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:129–135. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobruch J, Borówka A, Modzelewska E, et al. Prospective evaluation of prostate cancer stage at diagnosis in Poland-multicenter study. Cent European J Urol. 2009;62:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mettlin CJ, Murphy GP, Babaian RJ, et al. Observations on the early detection of prostate cancer from the American Cancer Society National Prostate Cancer Detection Project. Cancer. 1997;80:1814–1817. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971101)80:9<1814::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Draisma G, Boer R, Otto SJ, van der Cruijsen IW, Damhuis RA, Schröder FH, de Koning HJ. Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:868–878. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun Donald P, Digant Gupta, Edgar D. Staren. Predicting survival in prostate cancer: the role of quality of life assessment. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:1267–1274. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1213-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selli C, Bjartell A, Burgos J, et al. Burden of illness in prostate cancer patients with a low-to-moderate risk of progression: a one-year, pan-European observational study. Prostate Cancer. 2014:472949. doi: 10.1155/2014/472949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanagas G, Mickevičienė A, Ulys A. Does quality of life of prostate cancer patients differ by stage and treatment? Scand J Pubc Health. 2012;41:58–64. doi: 10.1177/1403494812467503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Tol-Geerdink JJ, Leer JW, van Oort IM, van Lin EJ, et al. Quality of life after prostate cancer treatments in patients comparable at baseline. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1784–1789. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]