Abstract

Macrophages play an essential and complicated role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. However, the regulation of macrophage autophagy as well as it role in the development of atherosclerosis is unclear. MicroRNA-384-5p (miR-384-5p) is a new miRNA that attracted attention very recently, while its effects on Beclin-1 and cell autophagy has not been reported. Here, we studied macrophage autophagy in ApoE (-/-) mice suppled with high-fat diet (HFD), a mouse model for atherosclerosis (simplified as HFD mice). We analyzed the levels of Beclin-1 and the levels of miR-384-5p in the purified F4/80+ macrophages from mouse aorta. Prediction of the binding between miR-384-5p and 3’-UTR of Beclin-1 mRNA was performed by bioinformatics analyses and confirmed by a dual luciferase reporter assay. We found that HFD mice developed atherosclerosis in 12 weeks, while the control ApoE (-/-) mice that had received normal diet (simplified as NOR mice) did not. Compared to NOR mice, HFD mice had significantly lower levels of macrophage autophagy, and significantly higher levels of macrophage death, resulting from decreases in Beclin-1. The decreases in Beclin-1 in macrophages were due to HFD-induced increases in miR-384-5p, which suppressed the translation of Bectlin-1 mRNA via 3’-UTR binding. Together, our study suggests that upregulation of miR-384-5p by HFD may impair the Beclin-1-mediated protection of macrophages through autophagy to accelerate the development of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, macrophage autophagy, ApoE (-/-), high fat diet (HFD), Beclin-1, miR-384-5p

Introduction

The key pathological events in atherosclerosis are chronic-inflammation-induced deposition of lipids and fibrous elements in the arterial wall large and medium-sized arteries. Atherosclerosis is the primary cause of heart disease and stroke, which accounts for many deaths in aged people. Atherosclerosis results from a maladaptive inflammatory response that is initiated by the intramural retention of cholesterol-rich, apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in susceptible areas of the arterial vasculature [1,2]. Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a well-known strong suppressor for atherosclerosis, in which it not only regulates lipoprotein cholesterol transport and controls cellular lipid regulation, but also inhibits inflammation occurrence [3,4]. In line with these notion, ApoE-deficient (ApoE -/-) mice display enhanced chronic inflammation in response to hypercholesterolemia, and enhanced acute immune response for bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [3-9]. High fat diet (HFD) induces development of atherosclerosis in ApoE -/- mice in 12 weeks, which has been used a model for experimental atherosclerosis [10-12].

Autophagy is a catabolic pathway that degrades and recycles cellular compartments for cell survival at various stresses, whereas its failure often leads to cell death [13]. Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) is a soluble cellular protein. During autophagy, autophagosomes engulf cytoplasmic components, resulting in conjugation of a cytosolic form of LC3 (LC3-I) to phosphatidylethanolamine to form LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3-II). Thus, the ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I represents the autophagic activity [13-15]. Autophagy-associated protein 6 (Atg6, or Beclin-1), ATG7 and p62 are several key autophagy-associated proteins that strongly induce autophagy in an independent or coordinated manner [16].

Lipoproteins that are sequestered in the arterial wall are susceptible to various modifications, which render these particles pro-inflammatory and which induce the activation of the overlying endothelial cells. The ensuing immune response is mediated by the recruitment of monocyte-derived cells into the sub-endothelial space, where they differentiate into macrophages that ingest the deposited lipoproteins, and then transform into the cholesterol-laden foam cells. Foam cells, typically classified as a type of macrophage, persist in plaques, which promotes disease progression. Hence, macrophages play a key role in the development of atherosclerosis [17-20].

Nevertheless, the study on the molecular mechanisms underlying the control the autophagy of macrophages in the development of atherosclerosis is lacking.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that regulate protein translation through their base-pairing with the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of the target mRNAs [21-27]. MiRNAs play essential roles in regulating atherosclerosis [5,28,29]. Among all miRNAs, miR-384-5p was only recently shown to play a role in the function of neural system [30,31]. Nevertheless, a role of miR-384-5p in the atherosclerosis has not been reported.

In the current study, we found that high-fat-diet (HFD) -treated ApoE (-/-) mice developed atherosclerosis in 12 weeks, while the control ApoE (-/-) mice that had received normal diet (simplified as NOR mice) did not. Compared to NOR mice, HFD mice had significantly more macrophage death, and significantly lower macrophage autophagy, resulting from decreases in Beclin-1. Moreover, the decreases in Beclin-1 in macrophages were due to HFD-induced increases in miR-384-5p, which suppressed the translation of Beclin-1 mRNA via 3’-UTR binding.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the US National Institutes of Health. All experiments were conducted under the supervision of the facility’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee according to an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol.

Mouse atherosclerosis model

Eight-week-old male ApoE (-/-) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) or bred in-house and maintained under sterile conditions and standard animal room conditions (temperature, 21 ± 1°C; humidity, 55-60%). The animals were randomly divided into two groups: the normal-diet group (NOR) and the high-fat diet (HFD) group. The animals of the HFD group were maintained for 12 weeks to induce atherosclerosis, after which the aortas were excised from the mice. The aortic roots along with the basal portion of the heart were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 hours, cryo-protected in 30% sucrose for 12 hours, and then embedded in OCT compound. The tissue was cross-sectioned into sections of 6 μm thickness. Atherosclerotic lesions of the aortic root were examined by H&E staining. Oil red O staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions to show the lipid deposition with an Oil red O staining kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Quantification of the images was measured using NIH ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD, USA). The data were calculated from 10 mice for each group. For each mouse, 3 slides that were 50 µm apart from each other were used for quantification.

Macrophage transfection

Culture media for primary mouse macrophages are DMEM media (Invitrogen, CA, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with endothelial cell growth factors, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were kept at 37°C with 5% CO2. Macrophages were transfected with miR-384-5p mimics, antisense for miR-384-5p (as-miR-384-5p) or null controls (RiboBio Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transfection efficiency was nearly 100%.

Apoptosis assay and flow cytometry

The cultured cells were re-suspended at a density of 106 cells/ml in PBS. After double staining with FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) from a FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), cells were analyzed using FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences) for determination of Annexin V+ PI- apoptotic cells, with Flowjo software (Flowjo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). For analyses and isolation of F4/80+ cells, the aorta was dissociated by 10 μg/ml trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 μg/ml DNase (Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA) for 35 minutes. After filtration at 30 μm, the single cell digests from mouse aorta were incubated with PE-cy7-F4/80 (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and then sorted on the FACScan flow cytometer.

Real-time RT-PCR

Aorta intimal RNA was isolated from mouse aortas. After cleaning with ice-cold PBS, mouse aortas were flushed with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) using an insulin syringe, and the eluate was collected in a 1.5 ml tube and prepared for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from tissue or cultured cells with miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was randomly primed from 2 μg of total RNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). RT-qPCR was subsequently performed in triplicate with QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). All primers were purchased from Qiagen. Data were collected and analyzed using 2-ΔΔCt method for quantification of the relative mRNA expression levels. Values of genes were first normalized against α-tubulin, and then compared to the experimental controls.

Western blotting

The cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (cOmplete ULTRA Tablets, Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA). After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and quantified. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were probed with rabbit anti-p62, rabbit anti-LC3, rabbit-anti-Beclin-1, rabbit-anti-ATG7 and rabbit-anti-α-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Secondary antibodies are HRP-conjugated against rat or rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA, USA). The protein levels were first normalized to α-tubulin, and then normalized to the experimental controls. Densitometry of Western blots was quantified with NIH ImageJ software.

MiRNA target prediction and 3’-UTR luciferase-reporter assay

MiRNAs targets were predicted as has been described before, using the algorithms TargetSan (https://www.targetscan.org) [32]. Luciferase-reporters were successfully constructed using molecular cloning technology. Plasmids for Beclin-1 miRNA 3’-UTR clone and Beclin-1 miRNA 3’-UTR with a site mutation at the miR-384-5p binding site were purchased from Creative Biogene (Shirley, NY, USA). MiR-384-5p-modified macrophages were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 hours, after which they were transfected with 1 μg of Luciferase-reporter plasmids per well. Luciferase activities were measured using the dual-luciferase reporter gene assay kit (Promega, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses

The data in this study are shown as the mean ± S.D. Differences among groups were analyzed using one-away ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction, followed by Fisher’ Exact Test for comparison of two groups (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). p<0.05 was considered significant.

Result

HFD induces atherosclerosis in ApoE (-/-) mice

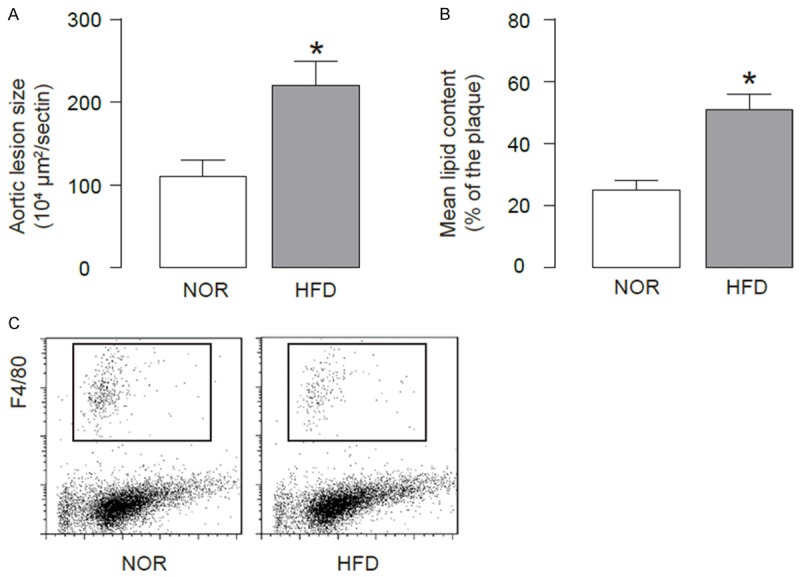

ApoE (-/-) mice were fed with High-fat diet (HFD; simplified as HFD mice) to induce experimental atherosclerosis in 12 weeks, which was confirmed by increases in aortic lesion size (Figure 1A), and by increases in lipid content in aortic sinus (Figure 1B), compared to littermate ApoE (-/-) mice that had received normal diet (NOR) as a control. Thus, HFD induces atherosclerosis in ApoE (-/-) mice. In order to analyze macrophages, we dissociated mouse aorta and purified macrophages based on F4/80 labeling by flow cytometry (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

HFD induces atherosclerosis in ApoE (-/-) mice. We used ApoE (-/-) mice treated with high-fat diet (HFD; simplified as HFD mice) for analyzing macrophage apoptosis. ApoE (-/-) mice that had received normal diet (NOR) were used as a control. (A, B) After a 12-week HFD treatment, analysis of H&E-stained histological sections of the aortic sinus showed a significant increase in aortic lesion size (A), and analysis of Oil-red-O-stained histological sections of the aortic sinus showed a significant increase in lipid content (B). (C) The aortas were dissociated and purified for macrophages based on F4/80 labeling by flow cytometry. *p<0.05. N=10.

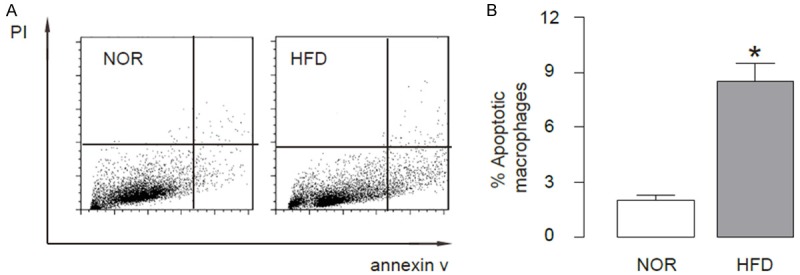

HFD induces apoptotic cell death of macrophages in ApoE (-/-) mice

Next, we examined the effects of HFD on macrophage apoptosis. We performed fluorescence-based apoptosis assay on the purified F4/80+ macrophages, and found significantly higher percentage of apoptotic macrophages in HFD mice, compared to NOR mice, shown by representative flow charts (Figure 2A), and by quantification (Figure 2B). These data suggest that HFD may induce apoptotic cell death of macrophages.

Figure 2.

HFD induces apoptotic cell death of macrophage in ApoE (-/-) mice. Fluorescence-based apoptosis assay was performed on the purified F4/80+ macrophages, showing significantly higher percentage of apoptotic macrophages in HFD mice, compared to NOR mice, shown by representative flow charts (A), and by quantification (B). *p<0.05. N=10.

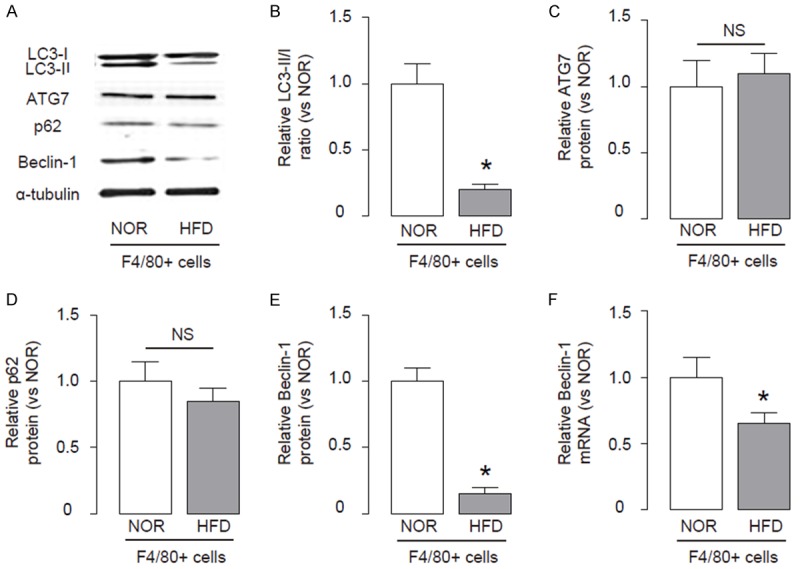

HFD impairs macrophage autophagy in ApoE (-/-) mice

Since apoptosis and autophagy often affect each other, we thus examined whether the increased apoptotic cell death of macrophages by HFD may occur concomitantly with alteration in macrophage autophagy. Therefore, we analyzed the autophagy levels in macrophages from HFD and NOR mice. We found that the LC3-II/I ratio significantly decreased in macrophages from HFD mice, than those from NOR mice, shown by representative immunoblots (Figure 3A), and by quantification (Figure 3B). Then we analyzed the levels of major autophagy-activators ATG7, p62 and Beclin-1 in macrophages from these mice, and found no difference in the levels of ATG7 and p62 between macrophages from HFD and NOR mice, shown by representative immunoblots (Figure 3A), and by quantification (Figure 3C, 3D). However, we detected a significant decrease in the levels of Beclin-1 in macrophages from HFD mice, compared to those from NOR mice, shown by representative immunoblots (Figure 3A), and by quantification (Figure 3E). These data suggest that HFD may inhibit Beclin-1 to impair macrophage autophagy, which may subsequently increase apoptotic cell death of macrophages. Interestingly, the mRNA level of BECLIN-1 was also decreased in macrophages from HFD mice, compared to those from NOR mice, but to a less pronounced degree, compared to protein changes (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

HFD impairs macrophage autophagy in ApoE (-/-) mice. (A-E) Immunoblots for apoptosis-associated genes LC3, ATG7, p62 and Beclin-1 in macrophages from HFD and NOR mice, shown by representative blots (A), and by quantification for ratio LC3-II vs I (B), ATG7 (C), p62 (D) and Beclin-1 (E). (F) RT-qPCR for mRNA of Beclin-1. *p<0.05. NS: non-significant. N=10.

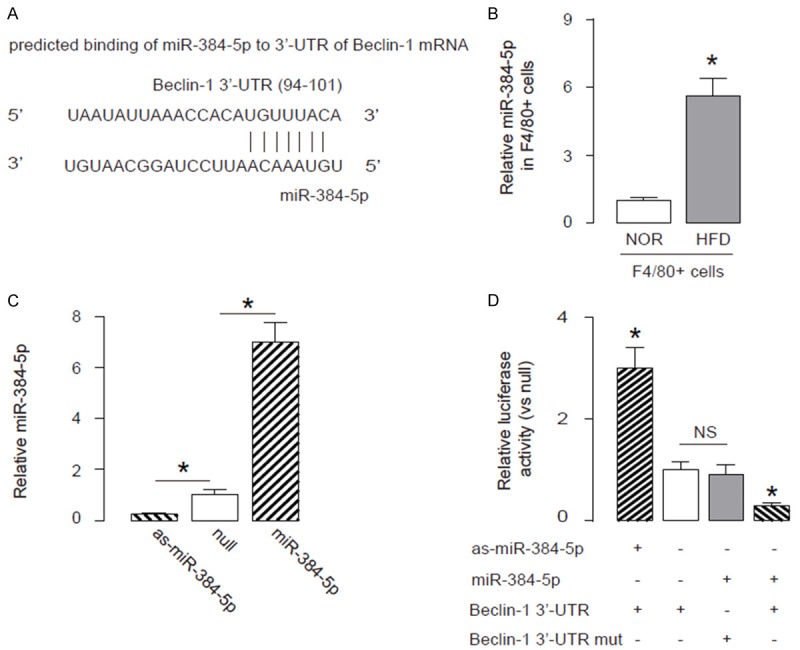

HFD impairs macrophage autophagy in ApoE (-/-) mice through suppressing the translation of Beclin-1 mRNA by miR-384-5p

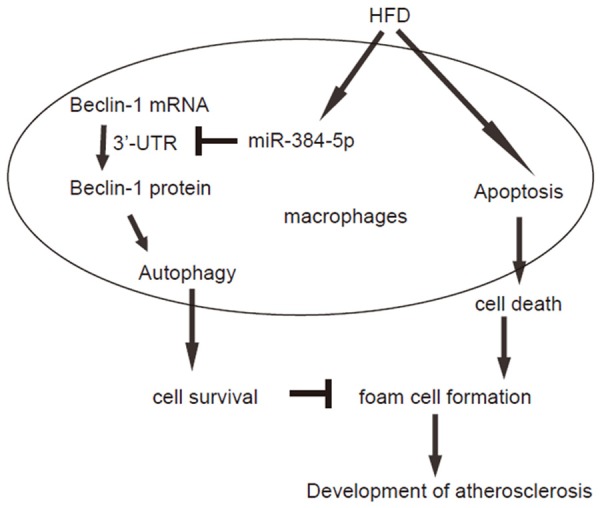

Next, we examined the underlying mechanisms. Since post-transcriptional control of gene expression is usually regulated miRNAs, we used bioinformatics analyses to screen all miRNAs that target Beclin-1 and altered their levels in macrophages in HFD mice. Specifically, we found that miR-384-5p targets 3’-UTR of Beclin-1 mRNA at one binding site (Figure 4A). Moreover, miR-384-5p levels in macrophages significantly increased after HFD treatment (Figure 4B). Hence, we modified miR-384-5p levels in macrophages, by transfection of the macrophages with miR-384-5p mimics, antisense for miR-384-5p (as-miR-384-5p) or null controls (null). First, modification of miR-384-5p levels in macrophages was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure 4C). Next, miR-384-5p-modified macrophages were transfected with 1 μg of Beclin-1 3’UTR luciferase-reporter plasmid or with 1 μg of Beclin-1 3’UTR luciferase-reporter plasmid with a site mutation at miR-384-5p binding site. The luciferase activities were quantified in these cells, suggesting that the binding of miR-384-5p to 3’-UTR of Beclin-1 mRNA results in suppression of Beclin-1 protein translation (Figure 4D). Thus, our study suggest that the failure of atherosclerosis-associated macrophage autophagy may result from HFD-induced downregulation of Beclin-1, through increased miR-384-5p that binds and suppresses translation of Beclin-1 mRNA (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

HFD impairs macrophage autophagy in ApoE (-/-) mice through suppressing the translation of Beclin-1 mRNA by miR-384-5p. A. Bioinformatics analyses showing that miR-384-5p targets 3’-UTR of Beclin-1 mRNA at one binding site. B. MiR-384-5p levels in macrophages from HFD or NOR mice. C. RT-qPCR for miR-384-5p in miR-384-5p-modified macrophages, prepared by transfection of the cells with miR-384-5p mimics, antisense for miR-384-5p (as-miR-384-5p) or null controls (null). D. MiR-384-5p-modified macrophages were transfected with 1 μg of Beclin-1 3’UTR luciferase-reporter plasmid (Beclin-1 3’-UTR) or with 1 μg of Beclin-1 3’UTR luciferase-reporter plasmid with a site mutation at miR-384-5p binding site (Beclin-1 3’-UTR mut). The luciferase activities were quantified. *p<0.05. NS: non-significant. N=10.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the model. The failure of atherosclerosis-associated macrophage autophagy may result from HFD-induced downregulation of Beclin-1, through increased miR-384-5p that binds and suppresses translation of Beclin-1 mRNA.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis include complex immune-inflammatory processes coordinated with endothelial cells, macrophages and smooth muscle cells. High glucose is a potent pro-atherosclerotic factor that has been widely used to induce experimental atherosclerosis in vivo, pronounced in ApoE (-/-) mice [10-12].

Aberrantly expressed miRNAs have recently been found to be involved in the regulation of macrophage survival/death, supported by many recent reports [33-35]. Gu et al. used next-generation sequencing to profile miRNA transcriptomes, and found that miR-384-5p specifically affect the maintenance, but not induction, of Long-term potentiation and different stages of spine enlargement by regulating the expression of RSK3 [30]. In another recent work, Ogata et al. reported that hippocampus-enriched miR-384-5p could be used as an indicators of neurotoxicity in serum [31]. However, a role of miR-394-5p in control of Beclin-1-mediated autophagy has not been acknowledged.

Here, we found that HFD significantly impaired macrophage autophagy, and this failure of autophagy significantly increased macrophage death, through augment in cell apoptosis. Importantly, we found that Beclin-1 was the effector protein regulated by HFD. Of note, here the decreases in Beclin-1 mRNA were much less pronounced than Beclin-1 protein. When a miRNA molecule is attached as a perfect match to a target mRNA, it causes the mRNA degradation, resulting in a decrease in mRNA levels. Here, it appeared that the connection between miR-384-5p and 3’-UTR of the Beclin-1 mRNA was not perfect, resulting in partial degradation of the mRNA. Moreover, since it is unlikely that Beclin-1 may be regulated by phosphorylation or acetylation in our experimental setting, we hypothesized that it might be regulated by miRNAs.

All Beclin-1-targeting miRNAs were then determined by bioinformatics analyses, and we screened all these miRNAs and found that surprisingly, not the well-known Beclin-1 regulators miR-30 [36,37], but miR-384-5p significantly increased in F4/80+ macrophages from HFD mice.

Previous studies have shown controversy on the exact role of macrophages in the development of atherosclerosis. Since macrophage autophagy could be a double-edged sword, in which it may increase the number and retention of the macrophages that release pro-inflammatory cytokines to sustain inflammation to aggravate the disease, it may also prevent the formation of foam cells. Thus, a delicate control of the time course and the levels of macrophage autophagy may be crucial for the prevention of atherosclerosis.

Together, our study identified a new role for miR-384-5p in the regulation of macrophage autophagy during atherosclerosis, and shed new insight into development of innovative therapy by targeting miR-384-5p in atherosclerosis treatment.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Schmitz G, Grandl M. Lipid homeostasis in macrophages - implications for atherosclerosis. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;160:93–125. doi: 10.1007/112_2008_802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liehn EA, Zernecke A, Postea O, Weber C. Chemokines: inflammatory mediators of atherosclerosis. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2006;112:229–238. doi: 10.1080/13813450601093583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dou L, Lu Y, Shen T, Huang X, Man Y, Wang S, Li J. Panax notogingseng saponins suppress RAGE/MAPK signaling and NF-kappaB activation in apolipoprotein-E-deficient atherosclerosis-prone mice. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29:875–882. doi: 10.1159/000315061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhi K, Li M, Zhang X, Gao Z, Bai J, Wu Y, Zhou S, Li M, Qu L. alpha4beta7 Integrin (LPAM-1) is upregulated at atherosclerotic lesions and is involved in atherosclerosis progression. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:1876–1887. doi: 10.1159/000362965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Yang L, Liang X, Zhu G. MicroRNA-155 Promotes Atherosclerosis Inflammation via Targeting SOCS1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:1371–1381. doi: 10.1159/000430303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jia EZ, An FH, Chen ZH, Li LH, Mao HW, Li ZY, Liu Z, Gu Y, Zhu TB, Wang LS, Li CJ, Ma WZ, Yang ZJ. Hemoglobin A1c risk score for the prediction of coronary artery disease in subjects with angiographically diagnosed coronary atherosclerosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34:672–680. doi: 10.1159/000363032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sattler K, Lehmann I, Graler M, Brocker-Preuss M, Erbel R, Heusch G, Levkau B. HDLbound sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) predicts the severity of coronary artery atherosclerosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34:172–184. doi: 10.1159/000362993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin J, Chang W, Dong J, Zhang F, Mohabeer N, Kushwaha KK, Wang L, Su Y, Fang H, Li D. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin over-expressed in human atherosclerosis: potential role in Th17 differentiation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;31:305–318. doi: 10.1159/000343369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu Y, Liu Z, Li L, Guo CY, Li CJ, Wang LS, Yang ZJ, Ma WZ, Jia EZ. OLR1, PON1 and MTHFR gene polymorphisms, conventional risk factors and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis in a Chinese Han population. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;31:143–152. doi: 10.1159/000343356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson AM, Li J, Samijono D, Bierhaus A, Thomas MC, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Cooper ME. Quinapril treatment abolishes diabetesassociated atherosclerosis in RAGE/apolipoprotein E double knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.05.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee S, Bedja D, Mishra S, Amuzie C, Avolio A, Kass DA, Berkowitz D, Renehan M. Inhibition of glycosphingolipid synthesis ameliorates atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness in apolipoprotein E-/- mice and rabbits fed a high-fat and -cholesterol diet. Circulation. 2014;129:2403–2413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavigiolio G, Jayaraman S. Proteolysis of apolipoprotein A-I by secretory phospholipase A(2): a new link between inflammation and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10011–10023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.525717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green DR, Levine B. To be or not to be? How selective autophagy and cell death govern cell fate. Cell. 2014;157:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo JY, Xia B, White E. Autophagy-mediated tumor promotion. Cell. 2013;155:1216–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145:341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bieghs V, Rensen PC, Hofker MH, Shiri-Sverdlov R. NASH and atherosclerosis are two aspects of a shared disease: central role for macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz C, Massberg S. Atherosclerosis--multiple pathways to lesional macrophages. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:239ps232. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang Y, Zhao Y, Gu W, Cao Y, Wang S, Pang J, Shi Y. Bufalin Inhibits the Differentiation and Proliferation of Cancer Stem Cells Derived from Primary Osteosarcoma Cells through Mir-148a. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:1186–1196. doi: 10.1159/000430289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji D, Li B, Shao Q, Li F, Li Z, Chen G. MiR-22 Suppresses BMP7 in the Development of Cirrhosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:1026–1036. doi: 10.1159/000430276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song W, Li Q, Wang L, Wang L. Modulation of FoxO1 Expression by miR-21 to Promote Growth of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:184–190. doi: 10.1159/000369686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G, Jiang C, Li D, Wang R, Wang W. MiRNA-34a inhibits EGFR-signaling-dependent MMP7 activation in gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:9801–9806. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang F, Xiao W, Sun J, Han D, Zhu Y. MiRNA-181c inhibits EGFR-signaling-dependent MMP9 activation via suppressing Akt phosphorylation in glioblastoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8653–8658. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q, Cai J, Wang J, Xiong C, Zhao J. MiR-143 inhibits EGFR-signaling-dependent osteosarcoma invasion. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:12743–12748. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Wang S, Lu L, Wei G. MiR99a modulates MMP7 and MMP13 to regulate invasiveness of Kaposi's sarcoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:12567–12573. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2577-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toba H, Cortez D, Lindsey ML, Chilton RJ. Applications of miRNA technology for atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16:386. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0386-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu XD, Zeng K, Liu WL, Gao YG, Gong CS, Zhang CX, Chen YQ. Effect of aerobic exercise on miRNA-TLR4 signaling in atherosclerosis. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35:344–350. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu QH, Yu D, Hu Z, Liu X, Yang Y, Luo Y, Zhu J, Li Z. miR-26a and miR-384-5p are required for LTP maintenance and spine enlargement. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6789. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogata K, Sumida K, Miyata K, Kushida M, Kuwamura M, Yamate J. Circulating miR-9* and miR-384-5p as potential indicators for trimethyltin-induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol Pathol. 2015;43:198–208. doi: 10.1177/0192623314530533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coronnello C, Benos PV. ComiR: Combinatorial microRNA target prediction tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W159–164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai Y, Chen H, Jin L, You Y, Shen J. STAT3-dependent transactivation of miRNA genes following Toxoplasma gondii infection in macrophage. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:356. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazumder A, Bose M, Chakraborty A, Chakrabarti S, Bhattacharyya SN. A transient reversal of miRNA-mediated repression controls macrophage activation. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao X, Gittes GK. Concise Review: New Insights Into the Role of Macrophages in beta-Cell Proliferation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:655–658. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T, Tian F, Wang J, Jing J, Zhou SS, Chen YD. Endothelial Cell Autophagy in Atherosclerosis is Regulated by miR-30-Mediated Translational Control of ATG6. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:1369–1378. doi: 10.1159/000430402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan W, Zhong Y, Cheng C, Liu B, Wang L, Li A, Xiong L, Liu S. MiR-30-regulated autophagy mediates angiotensin II-induced myocardial hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]