Abstract

Despite the recent appreciation of interleukin 35 (IL-35) function in inflammatory diseases, little is known for IL-35 response in patients with active tuberculosis (ATB). In the current study, we demonstrated that ATB patients exhibited increases in serum IL-35 and in mRNA expression of both subunits of IL-35 (p35 and EBI3) in white blood cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Consistently, anti-TB drug treatment led to reduction in serum IL-35 level and p35 or EBI3 expression. TB infection was associated with expression of p35 or EBI3 protein in CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells. Most p35+CD4+ T cells and EBI3+CD4+ T cells expressed Treg-associated marker CD25. Our findings may be important in understanding immune pathogenesis of TB. IL-35 in the blood may potentially serve as a biomarker for immune status and prognosis in TB.

Keywords: Human active pulmonary tuberculosis, interleukin-35, p35, EBI3, CD4+CD25+ T cells

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) has been becoming a top killer among infectious diseases (WHO data in 2014) despite the availability of anti-TB drugs and BCG vaccine [1]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection of humans induces immune responses of various T cell subpopulations including Th1, Th17 cells, Treg, CD8+ CTL and TB-reactive Vγ2Vδ2 T subset [2-5]. Nevertheless, whether T-cell immune responses in TB involve interleukin 35 (IL-35) remains poorly characterized.

IL-35, a member of the IL-12 family, was discovered by Stern, et al. in 1990, and initially named as cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor (CLMF) [6]. IL-35 is composed of the p35 subunit of IL-12 and the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-induced gene 3 (EBI3) subunit of IL-27. The anti-inflammatory role of IL-35 was described in 2007 by two separate research groups, Collison, et al., in the USA and Niedbala, et al., in the UK [7,8]. IL-35 appears to be produced by Treg cells, DC cells, B cells, macrophages, human placental trophoblasts, and various tumor cells of lung cancer, colon cancer, esophageal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, cervical carcinoma, melanoma, colorectal cancer and B cell lymphoma [8-22]. Like TGF-β and IL-10, IL-35 can induce development and expansion of a subset of Treg, named iTr35 [7,23]. Treg, a subset of CD4+ T cells, plays a key role in controlling autoimmunity and excessive immune responses in microbial infections by means of both cell-cell contact and secretion of inhibitory cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-35) [23]. IL-10 and TGF-β produced by mononuclear phagocytes have been shown to suppress T-cell responses during Mtb infection [24-31]. TGF-β increases the apoptosis of IFN-γ-producing T cells in both blood and Mtb infection sites [30,31]. A recent study has reported an increased expression of IL-35 elevated in tuberculosis pleural effusion [32]. However, a role of IL-35 in ATB and its exact relation with T cell subsets in TB remain unknown.

CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells have been shown to suppress T cell responses during infections through both IL-10-dependent and -independent pathways [33-35]. Treg cells may also contribute to attenuation of allergic airway inflammation in a TGF-β-dependent manner during both chronic and acute phases of Trichinella spiralis infection [36]. Furthermore, an increased frequency of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in TB has been prostituted to suppress immune responses of IFN-γ-producing T cells [37,38]. However, it is unclear how IL-35 coordinates the immune-regulatory properties of Treg in infectious diseases, although IL-35 can expand CD4+CD25+ Treg cells and enhance Treg suppressive function in inflammatory diseases and autoimmune diseases [7,8,39-41].

In this study, we examined the serum IL-35 level and the expression of IL-35 subsets (p35 and EBI3) in peripheral αβ T cell from patients with active tuberculosis (ATB). Our data suggest that IL-35 is involved in TB pathogenesis, and IL-35 level in the blood may be a valuable biomarker of immune status and prognosis in ATB.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Eighty cases of active pulmonary tuberculosis (ATB) in Dongguan 6st People’s Hospital (Dongguan, China) were evaluated in this study, and ATB was diagnosed as described previously [21,42]. Fourty healthy volunteers (HVs), without bacteriological and clinical evidence of TB, served as controls. Subjects with HIV infection, diabetes, cancer, autoimmune diseases, immunosuppressive treatment, or history of pulmonary TB were excluded from the study. All subjects were tested for sputum Ziehl-Neelsen acid fast staining and Lowenstein-Jensen slant culture according to the standard method. The individualized treatment of ATB patients was previously described. Patients with ATB were given initial anti-tubercular drug (ATD) treatments, namely M0 phase (duration, 0 to 4 days) and M1 phase treatment (duration, 20 to 40 days) as manifested by the absence of TB-relapsed symptoms. No significant differences in terms of age and gender were noted between patients and HVs. The study was approved by the Internal Review and the Ethics Boards of Guangdong Medical University and Dongguan 6st People’s Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from all study subjects.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum samples were collected after centrifugation and stored at -80°C until use. Serum IL-35 levels were detected using a human IL-35 ELISA kit (BlueGene, Shanghai, China) as described [21].

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction PCR analysis (qRT-PCR)

White blood cells (WBC) were harvested after lysis of red blood cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by standard Ficoll (GE Health, Fairfield, USA) density gradient centrifugation as previously described [21,42]. Total RNAs were isolated from PBMC using TRizol reagent (Takara, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScriptTMRT Master Mix kit (Takara, Dalian, China) and amplified for p35 and EBI3 using a SYBR® Premix Ex Taq TM II kit (Takara, Dalian, China). β-actin was used as an internal control. Primer sequences were as follows, EBI3: 5’-CAGCTTCGTGCCTTTCATAA-3’ (sense) and 5’-CTCCCACTGCACCTGTAGC-3’ (antisense); p35: 5’-CTTGTGGCTACCCTGGTCCTC-3’ (sense) and 5’-AGGTTTTGGGAGTGGTGAAGG-3’ (antisense); β-actin: 5’-TTGCCGACAGGATGCAGAA-3’ (sense) and 5’-GCCGATCCACACGGAGTACT-3’ (antisense). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on an ABI-7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The PCR reaction conditions were as follows: 30 s at 94°C, 5 s at 95°C, and 34 s at 60°C for 40 cycles, then for dissociation stage.

Flow cytometric analysis (FCM)

For flow cytometric detection of IL-35, 3~10×105 lymphocytes were surface stained with anti-human CD3, CD4 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA), and then intracellular stained with anti-human p35 and anti-human EBI3 (eBioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) as described previously [21]. Matched mouse IgG isotypes were used as negative controls. All samples were analyzed on a BD FACSCalibur™ II flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The normality evaluation was first performed to determine whether the data set was well-modeled with a normal distribution. If data passed the normality distribution evaluation, Student’s t test was used for 2-tailed comparisons; if data did not pass the normality, a Mann-Whitney U test was employed. Pearson correlation was used to measure the degree of dependency between variables by GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A P value of less than 0.05 (95% confidence interval) was considered as statistically significant, as previously described [42,43,52].

Results

ATB patients showed increases in soluble serum IL-35 cytokine and in mRNA expressions of IL-35 units in leukocytes and PBMC

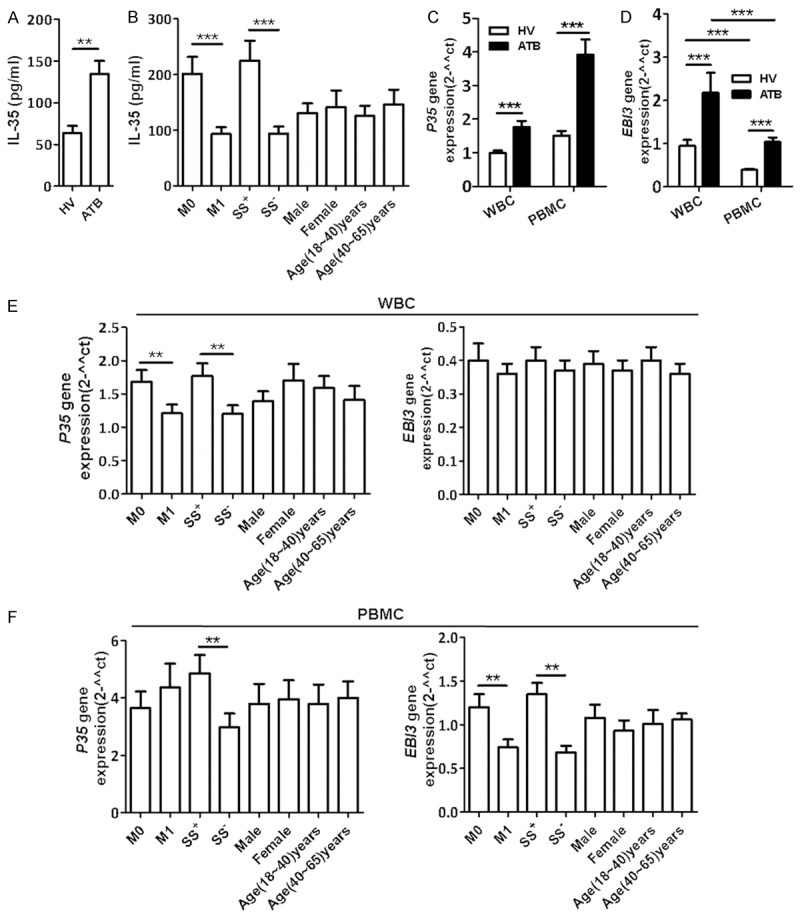

IL-35 has been reported to function as a novel anti-inflammatory cytokine, with potential therapeutic effects on autoimmune disorders (e.g., arthritis) [7,12,16], infectious diseases (e.g., salmonella) [16], transplantation (e.g., acute graft-versus-host disease), cancer (e.g., colorectal cancer) [21], and atherosclerosis [13,44]. To examine if IL-35 is involved in TB infection, we comparatively measure IL-35 levels in ATB patients and healthy controls. Serum samples isolated from 80 ATB patients and 40 HVs were used to measure IL-35 using ELISA. We found a significant increase in serum IL-35 level in patients with ATB (Figure 1A). The IL-35 level was particularly high in the patients whose sputum was Mtb-positive and those who started ATD treatment for only 0-4 days (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Mtb infection induced increases in serum IL-35 and mRNA expression of IL-35 units in leukocytes. ELISA was used to determine serum IL-35 in ATB patients (n=80) and healthy volunteers (HVs) (n=40). qRT-PCR was used to evaluate p35 and EBI3 mRNA expression in WBC or PBMC from ATB patients (n=30) or HVs (n=30). (A) Bar graph showing the concentration (pg/ml) of serum IL-35 in ATB patients and HVs. (B) Bar graph showing the concentration (pg/ml) of serum IL-35 in ATB patients treated with ATDs for 0 to 4 days (M0, n=37), or for 15 to 40 days (M1, n=38), patients with Mtb-positive sputum (n=40) or Mtb-negative sputum (n=40), patients with different gender (males, n=46; females, n=34) and ages (18-40 years, n=48; 40-60 years, n=32). (C and D) Bar graph showing mRNA expression of IL-35 subunits p35 (C) and EBI3 (D) in blood leukocytes (WBC and PBMC) from ATB patients or HVs. (E and F) Bar graph showing that the EBI3 and p35 gene expression in blood WBC (E) or PBMC (F) from groups of M0 (n=16), M1(n=14), sputum Mtb-positive (n=15) and sputum Mtb-negative (n=15), males (n=16), females (n=14), 18-40 years old (n=16), and 40-60 years old (n=14). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001.

To reveal IL-35 sources in blood, total RNA was isolated from WBC and PBMC of 30 patients with ATB and 30 HVs, and used to measure expression of IL-35 subunits p35 and EBI3 using qRT-PCR. Interestingly, p35 and EBI3 mRNA were up-regulated in both WBC and PBMC from patients with ATB. The relative expression of EBI3 mRNA, but not p35 mRNA, in WBC was higher than that in PBMC (Figure 1C and 1D). In addition, sputum Mtb-positive patients expressed higher p35 and EBI3 mRNA in WBC and higher EBI3 mRNA in PBMC than Mtb-negative patients (Figure 1E and 1F). Furthermore, EBI3 mRNA expression in PBMC appeared be affected by ATD treatment. Patients undergoing ATD treatment for 0-4 days showed a higher EBI3 mRNA expression than those who were treated for 20 to 40 days (Figure 1F). Together, these results suggest that Mtb infection increases IL-35 in both serum and leukocytes.

ATB patients exhibited increases in p35+CD4+ T cells and EBI3+CD4+ T cells, but not p35+ EBI3+CD4+ T cells

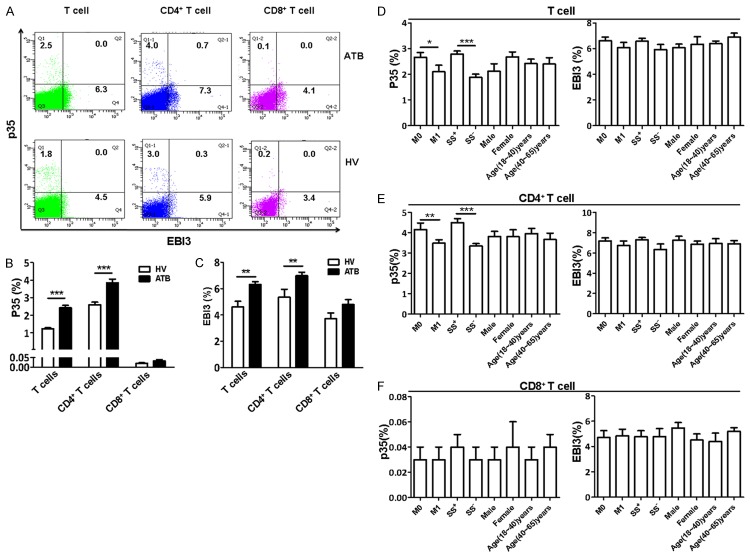

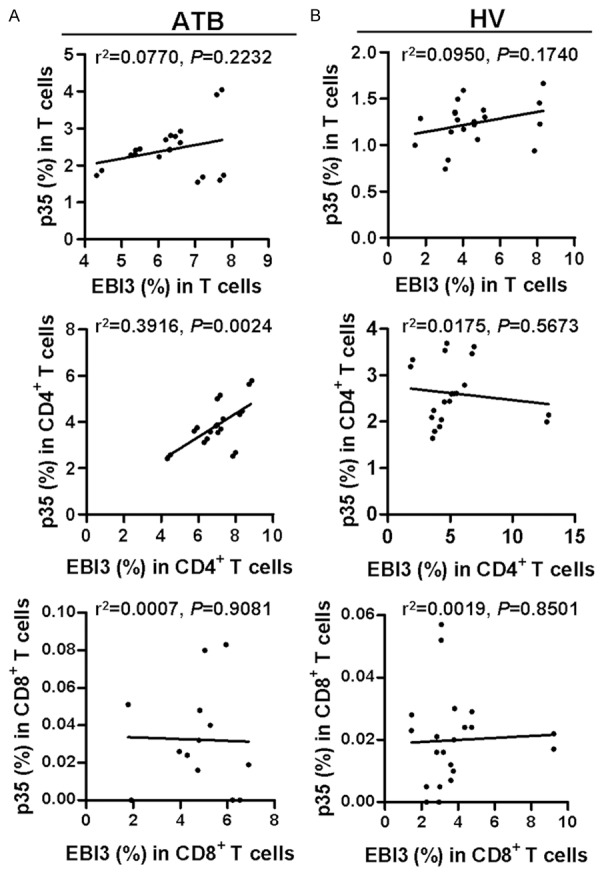

αβ T cells play an important role in adaptive immune responses against TB infection. To examine a potential role of IL-35 in αβ T cell response in TB, intracellular expressions of p35 and EBI3 in αβ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were measured by FCM analysis. Surprisingly, the expression of p35 or EBI3 was elevated in CD4+ T cells but not CD8+ T cells from patients with ATB. The numbers of p35+ CD8+ T cell subset and p35+ EBI3+ T cells were very low in both groups (Figure 2A-C). Additionally, p35 expression in T cells, especially in CD4+ T cells, was higher in sputum Mtb-positive patients than that in patients with Mtb-negative sputum (Figure 2D-F). Of note, the frequency of p35+CD4+ T cells was positively correlated to that of EBI3+CD4+ T cells in patients with ATB but not in HVs (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 2.

Mtb infection up-regulated p35 and EBI3 expression in CD4+ T cells. PBMC from ATB patients and HVs were stained and analyzed by polychromatic flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometric dot plots showing p35 and EBI3 expression in CD4 αβ T cells (CD3+CD4+) or CD8 αβ T cells subsets (CD3+CD4-T cells) from ATB patients (n=21) and HVs (n=21). (B) and (C) Bar graph showing the percentages of p35- (B) and EBI3- (C) producing T cells as of T cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells. (D)~(F) Bar graph showing the frequency of EBI3- and p35-producing T cells from different groups (M0, n=11; M1, n=10; sputum Mtb-positive, n=12; sputum Mtb-negative, n=9; male, n=10; female, n=11, 18-40 years old, n=11; 40-60 years old, n=10). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001.

Figure 3.

Associations among the percentages of p35 and EBI3 producing T cells within T cells, CD4+ T cells, or CD8+ T cells from ATB patients or HV individuals. Correlation of the percentages of p35- and EBI3-producing T cells within T cells, CD4+ T cells, or CD8+ T cells from ATB patients (A) or HVs (B) were analyzed by Pearson correlation using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0.

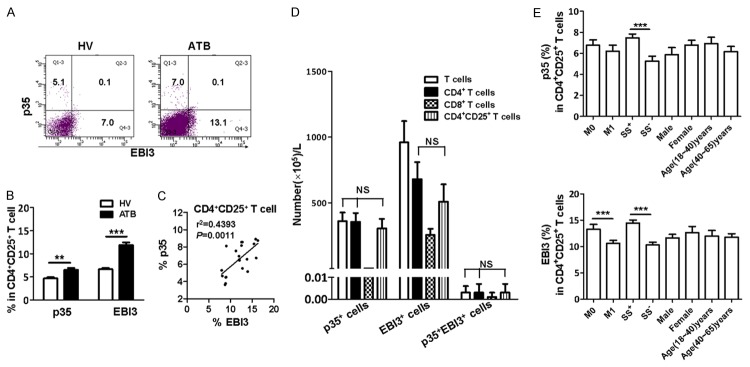

Most p35+CD4+ T cells and EBI3+CD4+ T cells express CD25 marker

Given that increased Treg is one of the characteristics in TB infection, we evaluated p35 or EBI3 expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells to determine whether they possess an inhibitory phenotype. Remarkably, p35 or EBI3 expressions in CD4+CD25+ T cells were increased in TB patients (Figure 4A and 4B), and the frequency of p35+CD4+CD25+ T cells was positively correlated to that of EBI3+CD4+CD25+ T cells in patients with ATB (Figure 4C). Interestingly, most p35+CD4+ T cells and EBI3+CD4+ T cells expressed CD25 (Figure 4D). Furthermore, the frequencies of p35+CD4+CD25+ T cells and EBI3+CD4+CD25+ T cells increased in sputum Mtb-positive ATB patients, when compared with sputum Mtb-negative patients (Figure 4E). Also, the frequency of EBI3+CD4+CD25+ T cells increased in patients who started to receive ATD treatment for 0-4 days (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Most p35+CD4+ T cell and EBI3+CD4+ T cell expressed CD25. PBMC from ATB patients and HVs were stained and analyzed by polychromatic flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometric dot plots showing p35 and EBI3 expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells from ATB patients (n=21) or HVs (n=21). (B) Bar graph demonstrating the percentages of p35- and EBI3-producing T cells within CD4+CD25+ T cells from ATB patients or HVs. (C) Correlation of the percentages of p35- and EBI3-producing cells within CD4+CD25+ T cells. (D) Bar graph showing the number (105/L) of EBI3+ T cells, p35+ T cells, and p35+EBI3+ T cells within T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+CD25+ T cells, respectively. (E) Bar graph showing the EBI3- and p35-producing CD4+CD25+ T cells from ATB patients with ATDs treatment for 0-4 days (M0, n=11), and for 15-40 days (M1, n=10), with sputum Mtb-positive (n=12) and sputum Mtb-negative (n=9), different genders (males, n=10; females, n=11), and different ages (18-40 years, n=11; 40-60 years, n=10). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001.

Discussion

To our knowledge, we demonstrated for the first time that TB patients exhibited increases in serum IL-35 cytokine and IL-35 subunits (p35 and EBI3) expression in leukocytes. In fact, TB infection is associated with increase in CD4+ T subset expressing single unit of IL-35, but not those expressing double units of IL-35 or CD8+ T cells expressing either of IL-35 units. However, we could not provide evidence that p35- or EBI3-expressing CD4+ T cells was the source of elevated serum IL-35. Importantly, most CD4+ T cells positive for either subunit of IL-35 expressed CD25. These findings suggest the expression of IL-35 subunits may be associated with immune regulation in ATB patients.

IL-35 was first identified as an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokine, and was mainly expressed upon stimulation [13,45]. IL-35 induces the development of iTr35 and is responsible for the suppressive function of regulatory B-cell (Breg) and Treg [7,12,46,47]. Recently, several groups have shown that IL-35 appears to play an immunomodulatory role in a wide variety of disease conditions. In a murine acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) model, IL-35 overexpression suppresses CD4+ T effector activation and induces expansion of Foxp3+ Tregs to modulate graft-versus-leukemia immune response [48]. We and others also found IL-35 could help to promote tumor (e.g., pancreas cancer, colorectal cancer) growth and angiogenesis [11,21,49]. A mathematical model developed by Liao, et al. based on previous experimental data also supports these findings [22]. Furthermore, circulating levels of IL-35 are aberrant in patients with multiple sclerosis [50-52], allergic asthma [51,52], inflammatory bowel disease [53], immune thrombocytopenia [54], portal hypertension [55], atherosclerosis [44], periodontitis [56], preeclampsia [57], hyperimmune-related diseases [20], coronary artery diseases [58], acute myeloid leukemia [17], allergic airways disease [59,60], chronic hepatitis B [61], and autoimmune and infectious diseases [12]. Here, we found circulating level of IL-35 is also aberrant in patients with ATB and may be involved in the disease pathogenesis.

It has been suggested that IL-35 is secreted by αβ T cells and IL-35 plays a role in CD4+CD25+ Treg expansion [39,41]. Here we found that p35 or EBI3 expressions in CD4+ T cells but not CD8+ T cells were increased in patients with ATB. Interestingly, p35 expression in CD8+ T cells and p35 and EBI3 co-expressions in αβ T cell were very low in both ATB patients and healthy controls. These results suggest that TB is associated with p35 or EBI3 expression in CD4+ T cells but not IL-35 (co-expression of p35 and EBI3) expression in CD4+ T cells. It is noteworthy that most p35+CD4+ or EBI3+CD4+ T cells also expressed CD25, suggesting that p35 or EBI3 expression in CD4+ T cells may be associated with regulatory T cell function in TB. It has been shown that p35 or EBI3 expression in CD4+ T cells is important for the immunomodulatory role, as Treg cells lacking either p35 or EBI3 cannot attenuate experimental inflammatory bowel disease in mice [53]. We demonstrate that in patients with ATB, most p35+CD4+ T cells and EBI3+CD4+ T cells also expressed Treg-related marker CD25. This finding may be relevant to the immunomodulatory role of IL-35 subunits in TB infection.

To examine whether IL-35 expression is associated with pathogenesis or prognosis of patients with ATB, we comparatively evaluate sputum Mtb-positive and -negative patients as well as patients who initiated ATD treatment for 0 to 4 days and those treated for 15 to 40 days. It is noted that patients with Mtb-positive sputum and patients treated for 0 to 4 days displayed higher levels of circulating IL-35, p35 and EBI3 mRNA in leukocytes, and p35 or EBI3 expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells. These results suggest that serum IL-35 level may have a potential prognostic value for patients with ATB.

In summary, we provided previously unreported data of IL-35 in patients with ATB. TB infection drove increases in serum IL-35 cytokine and p35 or EBI3 expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells. Consistently, bacterial control by ATD treatment reduces serum IL-35 level and p35 or EBI3 expression. p35+ CD4+ or EBI3+ CD4+ T cells express Treg-related marker CD25. Our findings may be important in understanding immune pathogenesis of TB. IL-35 in the blood may potentially serve as a biomarker for immune status and prognosis in TB.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570009, 81273237, 30972779, 81101553), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2015A030313513), the Key Project of Science and Technology Innovation of Education Department of Guangdong Province (2012KJCX0059), the Science and Technology Project of Dongguan (201450715200503), the Science and Technology Project of Zhanjiang (2013C03012) and the Science and Technology Innovation Fund of GDMC (STIF201110, B2012078).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Glaziou P, Sismanidis C, Floyd K, Raviglione M. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a017798. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geginat J, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Cytokine-driven proliferation and differentiation of human naive, central memory, and effector memory CD4(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1711–1719. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rozot V, Vigano S, Mazza-Stalder J, Idrizi E, Day CL, Perreau M, Lazor-Blanchet C, Petruccioli E, Hanekom W, Goletti D, Bart PA, Nicod L, Pantaleo G, Harari A. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells are functionally and phenotypically different between latent infection and active disease. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1568–1577. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marin ND, Paris SC, Rojas M, Garcia LF. Functional profile of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in latently infected individuals and patients with active TB. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013;93:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson RP, Shafiani S, Urdahl KB. Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in tuberculosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;783:165–180. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6111-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern AS, Podlaski FJ, Hulmes JD, Pan YC, Quinn PM, Wolitzky AG, Familletti PC, Stremlo DL, Truitt T, Chizzonite R, et al. Purification to homogeneity and partial characterization of cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor from human B-lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6808–6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niedbala W, Wei XQ, Cai B, Hueber AJ, Leung BP, McInnes IB, Liew FY. IL-35 is a novel cytokine with therapeutic effects against collagen-induced arthritis through the expansion of regulatory T cells and suppression of Th17 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3021–3029. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, Boyd K, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Cross R, Sehy D, Blumberg RS, Vignali DA. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature. 2007;450:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao H, Gao W, Ma C, Sun J, Liu J, Shao Q, Song B, Qu X. Human placental trophoblasts express the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-35. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardel E, Larousserie F, Charlot-Rabiega P, Coulomb-L’Hermine A, Devergne O. Human CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells do not constitutively express IL-35. J Immunol. 2008;181:6898–6905. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholl MB, Ledgewood CL, Chen X, Bai Q, Qin C, Cook KM, Herrick EJ, Diaz-Arias A, Moore BJ, Fang Y. IL-35 promotes pancreas cancer growth through enhancement of proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis: evidence for a role as an autocrine growth factor. Cytokine. 2014;70:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang RX, Yu CR, Dambuza IM, Mahdi RM, Dolinska MB, Sergeev YV, Wingfield PT, Kim SH, Egwuagu CE. Interleukin-35 induces regulatory B cells that suppress autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2014;20:633–641. doi: 10.1038/nm.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seyerl M, Kirchberger S, Majdic O, Seipelt J, Jindra C, Schrauf C, Stockl J. Human rhinoviruses induce IL-35-producing Treg via induction of B7-H1 (CD274) and sialoadhesin (CD169) on DC. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:321–329. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Y, Tao Q, Wang H, Xiong S, Zhang R, Chen T, Tao L, Zhai Z. Dendritic cells decreased the concomitant expanded Tregs and Tregs related IL-35 in cytokine-induced killer cells and increased their cytotoxicity against leukemia cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Liu JQ, Liu Z, Shen R, Zhang G, Xu J, Basu S, Feng Y, Bai XF. Tumor-derived IL-35 promotes tumor growth by enhancing myeloid cell accumulation and angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2013;190:2415–2423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen P, Roch T, Lampropoulou V, O’Connor RA, Stervbo U, Hilgenberg E, Ries S, Dang VD, Jaimes Y, Daridon C, Li R, Jouneau L, Boudinot P, Wilantri S, Sakwa I, Miyazaki Y, Leech MD, McPherson RC, Wirtz S, Neurath M, Hoehlig K, Meinl E, Grutzkau A, Grun JR, Horn K, Kuhl AA, Dorner T, Bar-Or A, Kaufmann SH, Anderton SM, Fillatreau S. IL-35-producing B cells are critical regulators of immunity during autoimmune and infectious diseases. Nature. 2014;507:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu H, Li P, Shao N, Ma J, Ji M, Sun X, Ma D, Ji C. Aberrant expression of Treg-associated cytokine IL-35 along with IL-10 and TGF-beta in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:1119–1123. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson BM, Jankowska-Gan E, Becker JT, Vignali DA, Burlingham WJ, McNeel DG. Human prostate tumor antigen-specific CD8+ regulatory T cells are inhibited by CTLA-4 or IL-35 blockade. J Immunol. 2012;189:5590–5601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long J, Zhang X, Wen M, Kong Q, Lv Z, An Y, Wei XQ. IL-35 over-expression increases apoptosis sensitivity and suppresses cell growth in human cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye S, Wu J, Zhou L, Lv Z, Xie H, Zheng S. Interleukin-35: the future of hyperimmune-related diseases? J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2013;33:285–291. doi: 10.1089/jir.2012.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng JC, Zhang Z, Li TY, Liang YF, Wang HM, Bao JJ, Zhang JA, Wang WD, Xiang WY, Kong B, Wang ZY, Wu BH, Chen XD, He L, Zhang S, Wang CY, Xu JF. Assessing the role of IL-35 in colorectal cancer progression and prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:1806–1816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao KL, Bai XF, Friedman A. Mathematical modeling of Interleukin-35 promoting tumor growth and angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dwivedi M, Kemp EH, Laddha NC, Mansuri MS, Weetman AP, Begum R. Regulatory T cells in vitiligo: Implications for pathogenesis and therapeutics. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsch CS, Toossi Z, Othieno C, Johnson JL, Schwander SK, Robertson S, Wallis RS, Edmonds K, Okwera A, Mugerwa R, Peters P, Ellner JJ. Depressed T-cell interferon-gamma responses in pulmonary tuberculosis: analysis of underlying mechanisms and modulation with therapy. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:2069–2073. doi: 10.1086/315114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch CS, Hussain R, Toossi Z, Dawood G, Shahid F, Ellner JJ. Cross-modulation by transforming growth factor beta in human tuberculosis: suppression of antigen-driven blastogenesis and interferon gamma production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3193–3198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong JH, Zhang M, Modlin RL, Linsley PS, Iyer D, Lin Y, Barnes PF. Interleukin-10 downregulates Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced Th1 responses and CTLA-4 expression. Infect Immun. 1996;64:913–918. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.913-918.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Attilio L, Bozza VV, Santucci N, Bongiovanni B, Didoli G, Radcliffe S, Besedovsky H, del Rey A, Bottasso O, Bay ML. TGF-beta neutralization abrogates the inhibited DHEA production mediated by factors released from M. tuberculosis-stimulated PBMC. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1262:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habib M, Tanwar YS, Jaiswal A, Arya RK. Tubercular arthritis of the elbow joint following olecranon fracture fixation and the role of TGFbeta in its pathogenesis. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16:288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H, Cheng C, Li M, Gao S, Li S, Sun H. Expression of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, TGF-beta, and IL-4 in the spinal tuberculous focus and its impact on the disease. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70:1759–1764. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0125-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch CS, Toossi Z, Vanham G, Johnson JL, Peters P, Okwera A, Mugerwa R, Mugyenyi P, Ellner JJ. Apoptosis and T cell hyporesponsiveness in pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:945–953. doi: 10.1086/314667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mustafa T, Bjune TG, Jonsson R, Pando RH, Nilsen R. Increased expression of fas ligand in human tuberculosis and leprosy lesions: a potential novel mechanism of immune evasion in mycobacterial infection. Scand J Immunol. 2001;54:630–639. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong X, Yang J. High IL-35 pleural expression in patients with tuberculous pleural effusion. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:1261–1268. doi: 10.12659/MSM.892562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belkaid Y, Piccirillo CA, Mendez S, Shevach EM, Sacks DL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendez S, Reckling SK, Piccirillo CA, Sacks D, Belkaid Y. Role for CD4(+) CD25(+) regulatory T cells in reactivation of persistent leishmaniasis and control of concomitant immunity. J Exp Med. 2004;200:201–210. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belkaid Y, Hoffmann KF, Mendez S, Kamhawi S, Udey MC, Wynn TA, Sacks DL. The role of interleukin (IL)-10 in the persistence of Leishmania major in the skin after healing and the therapeutic potential of anti-IL-10 receptor antibody for sterile cure. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1497–1506. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aranzamendi C, de Bruin A, Kuiper R, Boog CJ, van Eden W, Rutten V, Pinelli E. Protection against allergic airway inflammation during the chronic and acute phases of Trichinella spiralis infection. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:103–115. doi: 10.1111/cea.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro-Rodrigues R, Resende Co T, Rojas R, Toossi Z, Dietze R, Boom WH, Maciel E, Hirsch CS. A role for CD4+CD25+ T cells in regulation of the immune response during human tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Wu CY. CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells inhibit human memory gammadelta T cells to produce IFN-gamma in response to M tuberculosis antigen ESAT-6. Blood. 2008;111:5629–5636. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castellani ML, Anogeianaki A, Felaco P, Toniato E, De Lutiis MA, Shaik B, Fulcheri M, Vecchiet J, Tete S, Salini V, Theoharides TC, Caraffa A, Antinolfi P, Frydas I, Conti P, Cuccurullo C, Ciampoli C, Cerulli G, Kempuraj D. IL-35, an antiinflammatory cytokine which expands CD4+CD25+ Treg Cells. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2010;24:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bettini M, Castellaw AH, Lennon GP, Burton AR, Vignali DA. Prevention of autoimmune diabetes by ectopic pancreatic beta-cell expression of interleukin-35. Diabetes. 2012;61:1519–1526. doi: 10.2337/db11-0784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kochetkova I, Golden S, Holderness K, Callis G, Pascual DW. IL-35 stimulation of CD39+ regulatory T cells confers protection against collagen II-induced arthritis via the production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2010;184:7144–7153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng JC, Lin DZ, Yi LL, Liu GB, Zhang H, Wang WD, Zhang JA, Wu XJ, Xiang WY, Kong B, Chen ZW, Wang CY, Xu JF. BTLA exhibits immune memory for alphabeta T cells in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Transl Res. 2014;6:494–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng J, Song Z, Cai X, Huang S, Wang W, Zhu Y, Huang Y, Kong B, Xiang W, Lin D, Liu G, Zhang J, Chen CY, Shen H, Huang D, Shen L, Yi L, Xu J, Chen ZW. Tuberculous pleurisy drives marked effector responses of gammadelta, CD4+, and CD8+ T cell subpopulations in humans. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:851–857. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A0814-398RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin J, Kakkar V, Lu X. The role of interleukin 35 in atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:5151–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guttek K, Reinhold D. Stimulated human peripheral T cells produce high amounts of IL-35 protein in a proliferation-dependent manner. Cytokine. 2013;64:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collison LW, Chaturvedi V, Henderson AL, Giacomin PR, Guy C, Bankoti J, Finkelstein D, Forbes K, Workman CJ, Brown SA, Rehg JE, Jones ML, Ni HT, Artis D, Turk MJ, Vignali DA. IL-35-mediated induction of a potent regulatory T cell population. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olson BM, Sullivan JA, Burlingham WJ. Interleukin 35: a key mediator of suppression and the propagation of infectious tolerance. Front Immunol. 2013;4:315. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Wu Y, Wang Y, Cai Y, Hu B, Bao G, Fang H, Zhao L, Ma S, Cheng Q, Song Y, Liu Y, Zhu Z, Chang H, Yu X, Sun A, Zhang Y, Vignali DA, Wu D, Liu H. IL-35 mitigates murine acute graft-versus-host disease with retention of graft-versus-leukemia effects. Leukemia. 2015;29:939–946. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin P, Ren H, Sun W, Xin W, Zhang H, Hao J. Circulating IL-35 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jafarzadeh A, Jamali M, Mahdavi R, Ebrahimi HA, Hajghani H, Khosravimashizi A, Nemati M, Najafipour H, Sheikhi A, Mohammadi MM, Daneshvar H. Circulating levels of interleukin-35 in patients with multiple sclerosis: evaluation of the influences of FOXP3 gene polymorphism and treatment program. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;55:891–897. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0443-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong CK, Leung TF, Chu IM, Dong J, Lam YY, Lam CW. Aberrant expression of regulatory cytokine IL-35 and pattern recognition receptor NOD2 in patients with allergic asthma. Inflammation. 2015;38:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-0038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma Y, Liu X, Wei Z, Wang X, Xu D, Dai S, Li Y, Gao M, Ji C, Guo C, Zhang L, Wang X. The expression of a novel anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-35 and its possible significance in childhood asthma. Immunol Lett. 2014;162:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Wang Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zuo X, Li Y, Lu X. The possible role of the novel cytokines il-35 and il-37 in inflammatory bowel disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:136329. doi: 10.1155/2014/136329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Xuan M, Zhang X, Zhang D, Fu R, Zhou F, Ma L, Li H, Xue F, Zhang L, Yang R. Decreased IL-35 levels in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Dong J, Meng W, Ma J, Wang N, Wei J, Shi M. Effects of phased joint intervention on IL-35 and IL-17 expression levels in patients with portal hypertension. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:1131–1139. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalburgi NB, Muley A, Shivaprasad BM, Koregol AC. Expression profile of IL-35 mRNA in gingiva of chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis patients: a semiquantitative RTPCR study. Dis Markers. 2013;35:819–823. doi: 10.1155/2013/489648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozkan ZS, Simsek M, Ilhan F, Deveci D, Godekmerdan A, Sapmaz E. Plasma IL-17, IL-35, interferon-gamma, SOCS3 and TGF-beta levels in pregnant women with preeclampsia, and their relation with severity of disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:1513–1517. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.861415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin Y, Huang Y, Lu Z, Luo C, Shi Y, Zeng Q, Cao Y, Liu L, Wang X, Ji Q. Decreased plasma IL-35 levels are related to the left ventricular ejection fraction in coronary artery diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitehead GS, Wilson RH, Nakano K, Burch LH, Nakano H, Cook DN. IL-35 production by inducible costimulator (ICOS)-positive regulatory T cells reverses established IL-17-dependent allergic airways disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:207–215. e201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang CH, Loo EX, Kuo IC, Soh GH, Goh DL, Lee BW, Chua KY. Airway inflammation and IgE production induced by dust mite allergenspecific memory/effector Th2 cell line can be effectively attenuated by IL-35. J Immunol. 2011;187:462–471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu F, Tong F, He Y, Liu H. Detectable expression of IL-35 in CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood of chronic hepatitis B patients. Clin Immunol. 2011;139:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]