Abstract

Misfolding of proteins in the biosynthetic pathway in neurons may cause disturbed protein homeostasis and neurodegeneration. The prion protein (PrPC) is a GPI-anchored protein that resides at the plasma membrane and may be misfolded to PrPSc leading to prion diseases. We show that a deletion in the C-terminal domain of PrPC (PrPΔ214–229) leads to partial retention in the secretory pathway causing a fatal neurodegenerative disease in mice that is partially rescued by co-expression of PrPC. Transgenic (Tg(PrPΔ214–229)) mice show extensive neuronal loss in hippocampus and cerebellum and activation of p38-MAPK. In cell culture under stress conditions, PrPΔ214–229 accumulates in the Golgi apparatus possibly representing transit to the Rapid ER Stress-induced ExporT (RESET) pathway together with p38-MAPK activation. Here we describe a novel pathway linking retention of a GPI-anchored protein in the early secretory pathway to p38-MAPK activation and a neurodegenerative phenotype in transgenic mice.

Secretory or plasma membrane bound proteins are translated, folded and post-translationally modified in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi. The ER exerts quality control early in the secretory pathway1 and, therefore, many (but not all) folding-defective proteins are retained in the ER, translocated to the cytosol, polyubiquitinated and targeted to the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) for ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (reviewed in2,3). Overload of misfolded proteins challenges the ER capacity, leading to ER stress and induction of the unfolded protein response (UPR) to restore homeostasis (reviewed in4,5). When this stress becomes chronic, it results in cell death. In protein misfolding disorders, such as Alzheimer’s or prion diseases, chronic ER stress may contribute to neurodegeneration6,7,8.

The prion protein (PrPC), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein targeted to detergent resistant membranes (DRMs)9, plays fundamental roles in prion diseases, a group of fatal neurodegenerative disorders10,11,12. In humans, they can be sporadic (e.g. sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD)), genetic (e.g. Gerstman-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS) or Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI)) or acquired (iatrogenic CJD (iCJD) or new variant CJD (vCJD)). A key event in the pathogenesis of prion diseases is the misfolding of PrPC to PrPSc, biochemically characterized by its insolubility and partial resistance towards proteinase K digestion.

PrP variants that lack the GPI-anchor are mainly degraded by ERAD13,14,15,16,17, while GPI-anchored variants of PrP containing mutations within the globular C-terminal domain are not amenable to ERAD18. Instead, GPI-anchored mutants of PrP, both artificially constructed mutants and naturally occurring disease mutants, undergo RESET (Rapid ER Stress-induced ExporT) pathway prior degradation19. RESET is a stress-inducible pathway by which diverse misfolded GPI-anchored proteins dissociate from ER-resident chaperones, bind to ER export factors and traffic to the Golgi. After RESET, they transiently appear on the plasma membrane before being endocytosed for lysosomal degradation.

We have studied a C-terminal deletion mutant of PrPC (PrPΔ214–229) in neuronal cell lines and transgenic mice. We expected our mutant to cause a clear phenotype for two main reasons. On the one hand, point mutations at alpha helices 2 and 3 (α2 and α3) lead to genetic prion disease13,14,15 and its total deletion in mice leads to intraneuronal PrP aggregates20. On the other hand, shedding of PrPC occurs between Gly228 and Arg229 by the sheddase ADAM10 and substrate recognition is achieved by a steric motive21,22. Shedding of PrPC helps to maintain PrPC homeostasis at the plasma membrane and shed forms of PrPC, found in CSF and blood, hold important functions. Thus, alterations in the recognition site of ADAM10-mediated shedding23,24 may lead to absence of presumably neuroprotective functions of shed PrPC25,26.

PrPΔ214–229 is GPI-anchored and characterized by an immature glycosylation status. In cell culture, PrPΔ214–229 is partially retained in the ER and under stress conditions, it reaches the trans-Golgi network (TGN) where it is retained, suggestive of a RESET pathway that does not undergo subsequent degradation to the lysosomes. Transgenic mice expressing PrPΔ214–229 (Tg(PrPΔ214–229)) present with neurodegeneration and a fatal neurological disease with increased p38-MAPK phosphorylation. Activation of p38-MAPK is also seen in cell culture under stress conditions. Thus, we show that retention in the secretory pathway of a misfolded GPI-anchored protein can be associated with a specific signaling pathway, leading to neurodegeneration in mice, with potential implications in human prion diseases.

Results

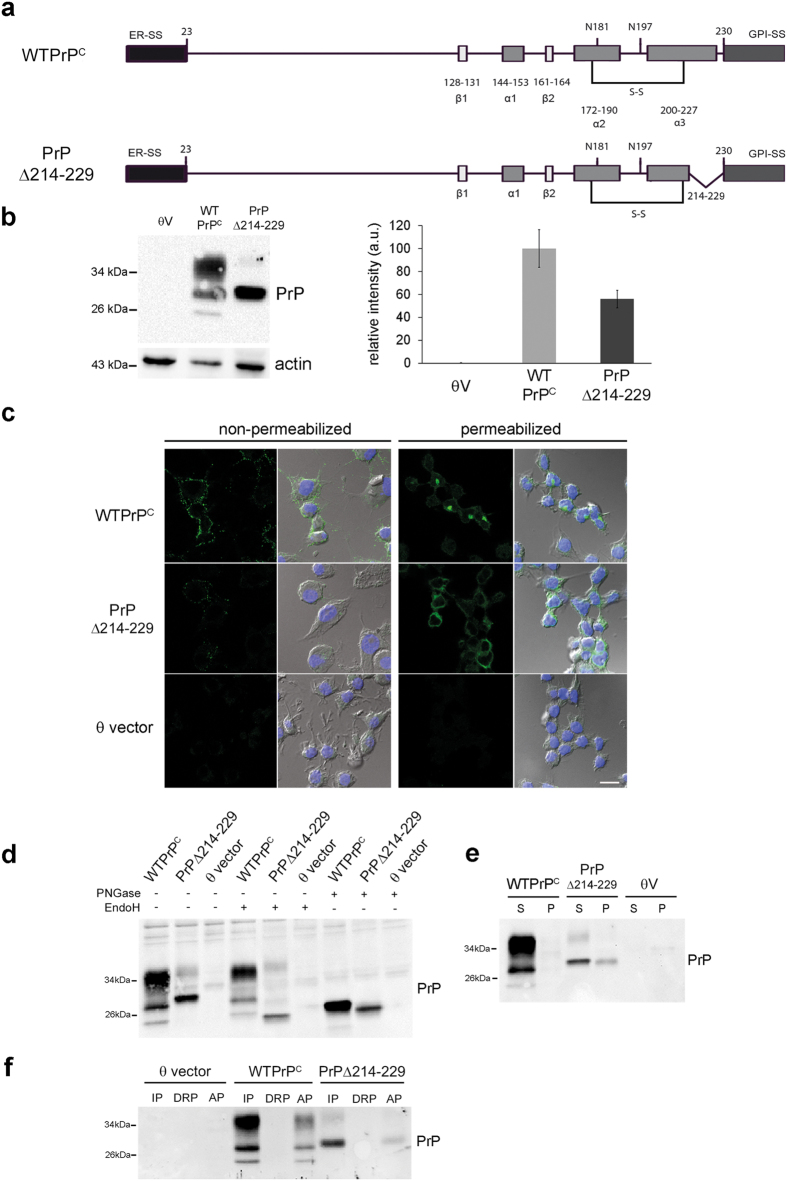

The C-terminal deletion (Δ214-229) in PrPC interferes with maturation in the secretory pathway

It has been described that misfolded GPI-anchored PrP follows an alternative ERAD pathway for degradation18,19. We have deleted 16 C-terminal amino acids (PrPΔ214–229) leaving the disulfide bond (amino acid 178–213) and the GPI-anchor attachment site (omega site, Ser230) intact (Fig. 1a). We generated mouse neuroblastoma cells (N2a) stably expressing wild-type PrPC (WTPrPC) or PrPΔ214–229. The presence of the 3F4 tag allowed us to discriminate between endogenous PrPC and transfected constructs. Cells transfected with PrPΔ214–229 expressed a main band at around 29 kDa when assessed by Western blot (Fig. 1b) in a proportion about ~60% of the amount of WTPrPC. Confocal microscopy showed plasma membrane localization (non-permeabilized cells) and perinuclear localization (permeabilized cells) for WTPrPC. PrPΔ214–229 showed reduced expression at the plasma membrane and diffuse intracellular staining (Fig. 1c). Digestion of cell lysates with Endoglycosidase H (EndoH, cleaving immature mannose-rich oligosaccharides) and N-Glycosidase F (PNGase F, removing all N-linked glycans) as well as a Triton X-114 assay27 confirmed presence of non-complex glycans and GPI-anchorage for PrPΔ214–229 (Fig. 1d,e). To study solubility of PrPΔ214–229, samples were treated with Triton X-100 and separated in pellet (insoluble) and supernatant (soluble) fractions by centrifugation. PrPΔ214–229 was present in the pellet fraction indicative of misfolding (Fig. 1f). In order to exclude a cell type bias, we also investigated transfected neuroblastoma SHSY5Y cells (presenting negligible levels of endogenous PrPC). As in N2a cells, PrPΔ214–229 in SHSY5Y cells was EndoH sensitive (Supplementary Fig. 1a), partially insoluble (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and mainly resided in intracellular compartments (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Characterization of WTPrPC and PrPΔ214-229 in stably transfected N2a cells.

(a) Schematic illustration of the constructs used in the study (mouse sequence). ER-SS: ER signal sequence; α 1–3: α-helices; β1, 2: β strands; S-S: disulfide bond; N181 and N196: N-linked oligosaccharide chains; GPI-SS: signal sequence for GPI-anchor attachment. In PrPΔ214–229 the deletion between residues 214–229 is shown. (b) Western blot developed with the 3F4 antibody. PrPΔ214–229 expresses mainly an immature band at around 29 kDa. θV are cells transfected with empty vector. The graphic shows the quantification of expression levels where the amount of WTPrPC is set to 100%. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). (c) Representative immunofluorescence of PrP (detected with 3F4 antibody; green) under non-permeabilizing and permeabilizing conditions. Under non-permeabilizing conditions it can be observed that less PrPΔ214–229 reaches the plasma membrane compared to WTPrPC. Under permeabilizing conditions PrPΔ214–229 shows diffuse intracellular staining. Scale bar is 10 μm. (d) Treatment of stably transfected N2a cells with EndoH shows that, as expected, WTPrPC is completely resistant to enzymatic digestion whereas PrPΔ214–229 is sensitive. Treatment with PNGase F shows that in both constructs bands decrease in size and are brought to the size of the unglycosylated isoform. (e) After treating cell lysates with Triton X-100 and separating the supernatant (S) from the pellet (P) by centrifugation, PrPΔ214–229 is found in the pellet (P) fraction, indicative of aggregation. (f) Triton X-114 phase separation assay. IP: insoluble pellet where GPI-anchor proteins are mainly found; DRP: detergent-resistant phase; AP: soluble phase. Note that PrPΔ214–229 is also found in the IP fraction, indicating GPI-anchoring.

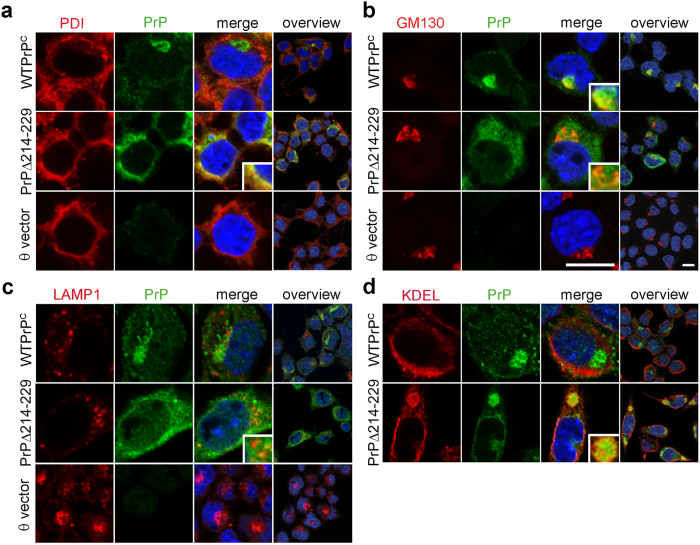

Co-staining with protein markers of ER (PDI), Golgi (GM130) and lysosomes (LAMP1) showed co-localization of WTPrPC with the Golgi apparatus and the plasma membrane as described28, whereas PrPΔ214–229 was mainly found in the ER (Fig. 2a). Only rarely could we observe lysosomal localization of WTPrPC or PrPΔ214–229 (Fig. 2c), mainly in cells with high PrPΔ214–229 expression (Fig. 2c, inset). Interestingly, clusters of ER-resident chaperones containing the KDEL motif colocalized with PrPΔ214–229 (Fig. 2d) implying a response to improper folding.

Figure 2. PrPΔ214–229 is mainly retained in the ER in N2a cells.

(a) Confocal microscopy of double immunocytochemistry for PrP (detected with 3F4 antibody; green) with PDI (ER marker; red) or (b) GM130 (Golgi marker; red). Whereas WTPrPC mainly colocalizes with GM130, PrPΔ214–229 colocalizes with PDI, although some degree of colocalization is seen with GM130 (b inset). Scale bar is 10 μm. (c) Confocal immunocytochemistry for PrP and the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (red). In few instances a partial colocalization with LAMP1 is seen for PrPΔ214–229 (c, inset). (d) Labeling of KDEL chaperones (in red) colocalizing with PrPΔ214–229 (detected with 3F4 antibody; green).

Taken together, we could show that PrPΔ214–229 in neuronal cells is GPI-anchored, immaturely glycosylated and mainly retained in the ER.

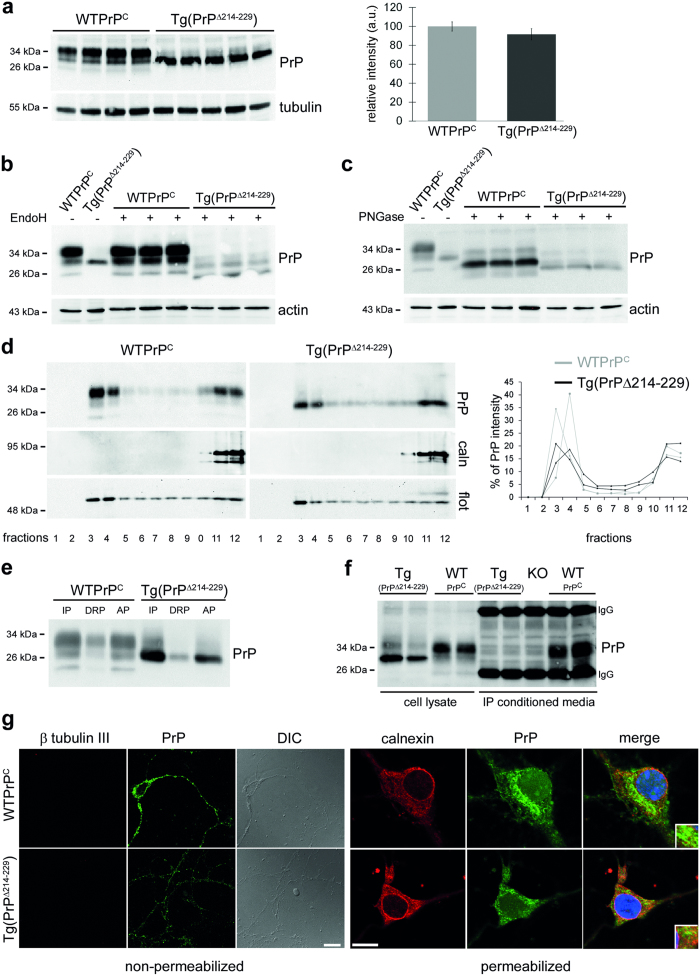

Expression of PrPΔ214–229 leads to a fatal neurological disease in mice

To study the consequences of the ER retention in vivo we generated transgenic mice expressing PrPΔ214–229. Two lines of transgenic mice were generated on a PrPC knock-out background, with one line showing low expression (Supplementary Fig. 2) and one line expressing physiological levels of PrPΔ214-229 (Fig. 3a). We observed the three banding pattern for PrPC in control mice (WTPrPC), whereas Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice showed a prominent band at ~29 kDa and a very weak band at ~35 kDa (Fig. 3a). After EndoH or PNGaseF digestion of brain homogenates (Fig. 3a–c), we observed EndoH sensitive glycans in Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice, suggesting lack of conversion into complex structures, as observed with N2a and SHSY5Y cells. Of note, a very faint fraction of PrPΔ214–229 showed complex glycosylation suggesting that a subset can be further processed in the secretory pathway. After Triton X-114 phase separation assay, PrPΔ214–229 from brain homogenates was mainly present in the insoluble pellet (IP) suggesting GPI-anchorage (Fig. 3e). Moreover, after solubilization with Triton X-100 and sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, it mainly localized to DRMs (Fig. 3d), further demonstrating GPI-anchorage. Immunocytochemistry of primary neurons under non-permeabilizing conditions showed reduced plasma membrane levels of PrPΔ214–229 (Fig. 3g). Under permeabilizing conditions, a diffuse intracellular staining is observed for PrPΔ214–229, colocalizing with the ER marker calnexin (Fig. 3g). No proteolytically shed PrPΔ214–229 was detected in conditioned media of primary neurons (Fig. 3f) indicating that PrPΔ214–229 is mainly retained at the secretory pathway and, as a consequence, ADAM10-mediated shedding is absent.

Figure 3. Characterization of transgenic PrPΔ214–229 mice (Tg(PrPΔ214–229)).

(a) Representative Western blot (detected with POM1 antibody) of frontal cortex brain homogenates. PrPΔ214–229 presents a main band at ~29 kDa with a faint upper band. The graphic shows quantification of expression levels. The amount of WTPrPC is set to 100%. Error bars indicate SEM. (b) Brain homogenates treated with EndoH. PrPΔ214–229 is largely EndoH sensitive although a minor fraction is non-sensitive (note the presence of an upper glycosylated band). (c) Treatment with PNGase F digests PrP to the size of the non-glycosylated isoform in both Tg(WTPrPC) and Tg(PrPΔ214–229) brain homogenates. (d) DRMs isolation. Both, WTPrPC and PrPΔ214–229 are mainly found in fractions 3 and 4 (as shown in the graph on the right) indicating presence in lipid raft. Flotillin (flot) is a lipid raft marker and calnexin (caln) is a non-lipid raft fraction marker. (e) Triton X-114 phase separation assay. IP: insoluble pellet where GPI-anchor proteins are mainly found; DRP: detergent-resistant phase; AP: soluble (aqueous) phase. PrPΔ214–229 is found in the IP fraction indicating GPI-anchoring. (f) Analysis of PrP shedding in primary neurons. Shed PrP was immunoprecipitated (IP) from conditioned media using POM2 antibody and assessed in parallel with cell lysates by Western Blot. Primary neurons from Prnp knock-out mice (KO) served as negative control. No shed PrP was detected in the conditioned media of Tg(PrPΔ214–229) neurons. IgG: capturing antibody bands. (g) Confocal microscopy of PrP (POM1 antibody; green) in hippocampal primary neurons under non-permeabilizing and permeabilizing conditions. Under non-permeabilizing conditions, PrPΔ214–229 can only partially reach the plasma membrane. β tubulin III (red) proves lack of intracellular staining. DIC is phase contrast. Under permeabilizing conditions, PrPΔ214–229 presents a diffuse staining partially colocalizing with calnexin (red) used as an ER marker whereas PrPC, although also partially colocalizing with calnexin, seems to be mainly present in another organelle presumably Golgi, as observed in N2a cells (Fig. 2). Scale bar is 10 μm.

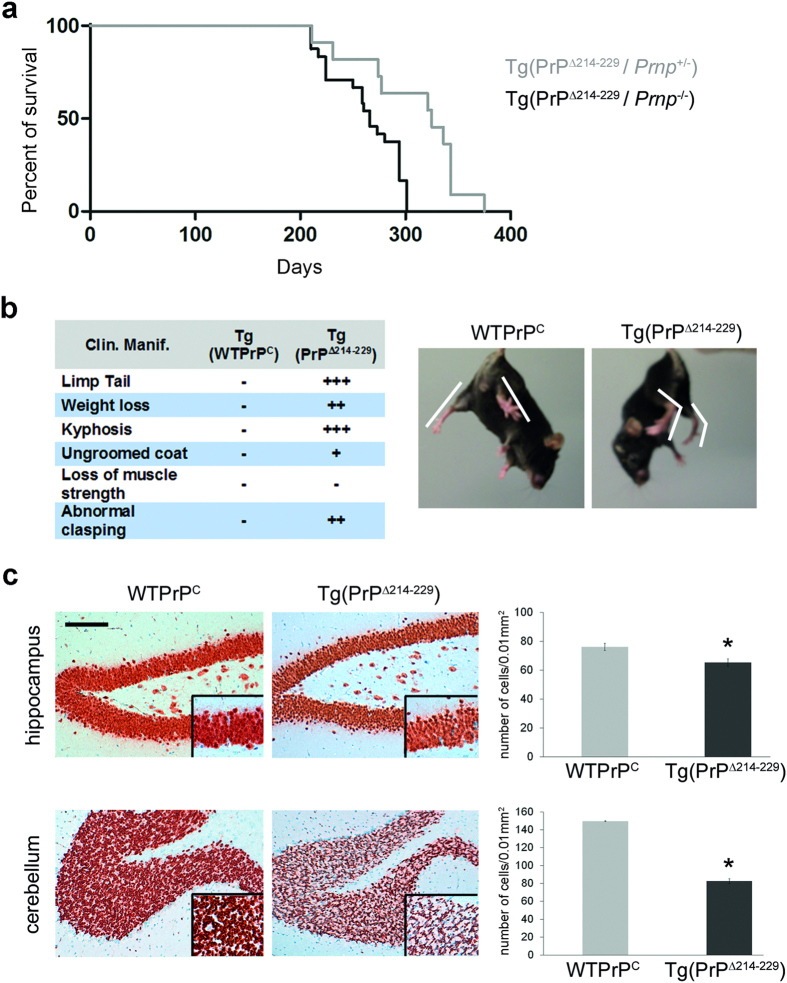

Interestingly, Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice developed a progressive fatal neurological disease with a mean survival time of 270.28 ± 6.47 days (Fig. 4a,b; Supplementary Fig. 3a). Genetic reintroduction of one allele of wild-type Prnp partially rescued the phenotype and prolonged survival to 315 ± 15.12 days (Fig. 4a; Breslow (generalized Wilcoxon) test (*p = 0.01)) arguing in favor of PrP-dependent effects. Neuropathologically, a significant neuronal loss in the cerebellar granular layer (Student’s t-test, p = 0.044) and the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 4c; t-test p = 0.002) with discrete spongiosis in white matter and no obvious astro- or microgliosis was seen (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Figure 4. Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice present with a neurological disease and die around 38 weeks of age with loss of hippocampal and cerebellar granular neurons.

(a) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice (black, n = 21) and Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice backcrossed with C57BL/6 wild-type mice expressing one allele of PrPC (Tg(PrPΔ214–229/PrP+/−) (grey, n = 10). There is a significant delay to terminal stage of disease in Tg(PrPΔ214-229/PrP+/−) mice. ***p < 0,001 (p-values are given in the main text). (b) Clinical manifestations of Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice. As shown in the pictures, Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice present with absence of clasping but presence of an abnormal leg spreading when lifted at the tail. (c) Representative pictures of NeuN staining in cerebellum and hippocampus. Neuronal loss in Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice is mainly observed in the granular cell layer and in the hippocampal CA1 layer. Quantifications show number of cells/0.01 mm2 for hippocampal CA1 layer and cerebellar granular layer (t-test: *p < 0.05). Error bars represent SEM.

Activation of p38-MAPK correlates with neurodegeneration and disease in Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice

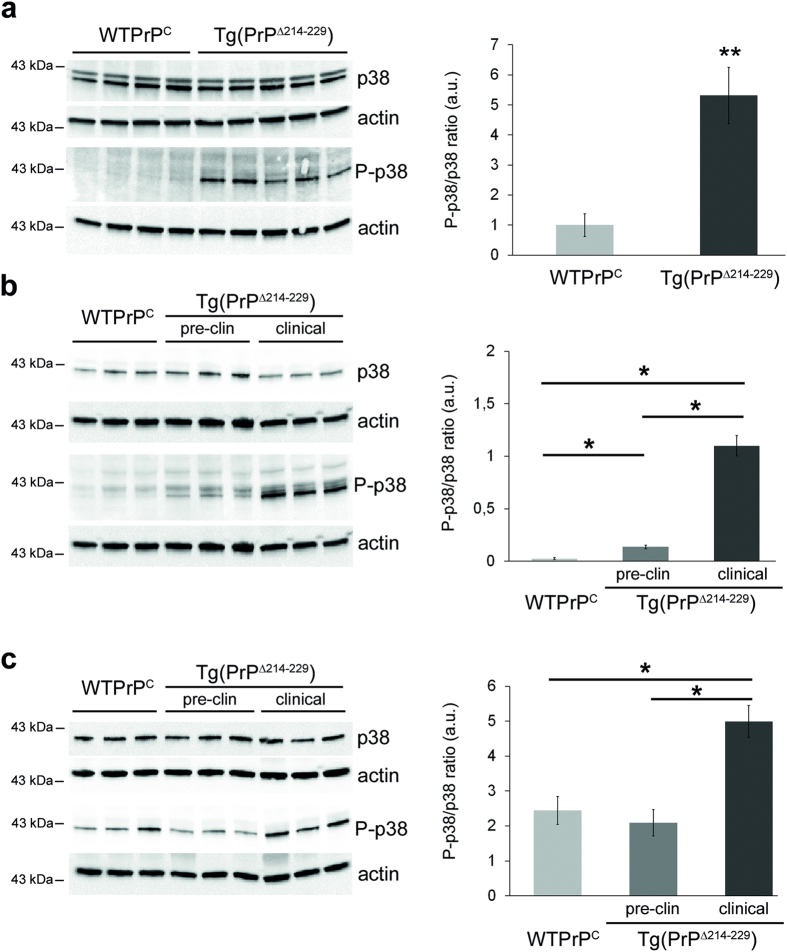

The fact that PrPΔ214–229 is retained at the biosynthetic pathway and sensitive to EndoH digestion, prompted us to investigate cell death pathways linked to ER stress. We could not detect induction of UPR signaling pathways (upregulation of CHOP, increase in cleaved ATF6, phosphorylated eIF2a) in Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). Strikingly, we observed a clear increase of phosphorylated p38-MAPK (P-p38-MAPK) in the forebrain at clinical and pre-clinical time points (t-test: WTPrPC versus clinical Tg(PrPΔ214–229) forebrain, p = 0.006; WTPrPC versus clinical Tg(PrPΔ214–229), p = 0.0083) and in cerebellum at clinical time points (WTPrPC versus clinical Tg(PrPΔ214–229), p = 0.026) (Fig. 5). Other putative prion-associated signaling pathways such as phosphorylation of Fyn29,30, JNK, ERK, STEP, c-PLA231,32,33 or associated to prion-driven calcium disturbances34 such as calpain, were unaltered (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c).

Figure 5. p38-MAPK is activated in brains of terminally-diseased and preclinical Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice.

(a) Western blots of forebrain homogenates from age-matched Tg(WTPrPC) (n = 4) and terminally-diseased Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice (n = 5). Levels of total p38-MAPK are unchanged, whereas P-p38-MAPK (T180/Y182) is increased. Actin is used as a loading control. For densitometric analysis, intensities of P-p38-MAPK and p38-MAPK signals were first referred to their corresponding actin and then the ratio P-p38-MAPK to p38-MAPK was calculated. (b) Western blots of forebrain homogenates from age-matched Tg(WTPrPC) and Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice either at a preclinical time point (17 weeks of age) or in clinical mice. The ratio P-p38/p38 was calculated as described before. (c) Western blots of cerebellar homogenates of Tg(WTPrPC) and Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice at time points described in (b). Error bars show SEM (p-values of Student´s t-test are given in the main text). **p < 0.005; *p < 0.05.

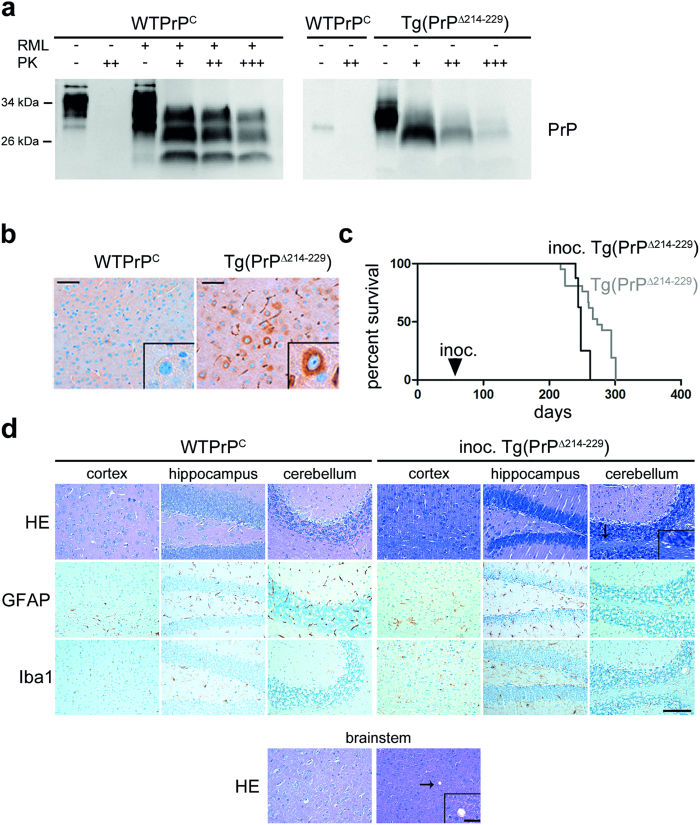

PrPΔ214–229 is partially proteinase K (PK) resistant and accelerates disease in syngeneic hosts

When PrP is mutated and retained in the ER, it adopts features similar to PrPSc such as partial PK resistance and insolubility in non-ionic detergents28. Thus, we assessed PK resistance at a concentration widely used to define PrPSc (Fig. 6). PrPΔ214–229 from brain homogenates was partially resistant to PK digestion yet transmission experiments into highly prion-sensitive tga20 indicator mice (n = 12) did not show detectable titers of prion infectivity when inoculated with pre-clinical (42 days old; n = 1) or clinical (280 days old; n = 2) brain homogenates. All tga20 mice remained healthy >250 days post inoculation.

Figure 6. PrPΔ214–229 is partially PK resistant and accelerates disease in syngeneic host.

(a) Western blot analyses of PrP in brain homogenates after PK digestion. 4 μl of 10% total brain homogenate were treated with increasing amounts of PK (10 μg/ml (+); 20 μg/ml (++) and 40 μg/ml (+++)). A wild type prion diseased mouse (inoculated with RML prions) was used as a positive control. WTPrPC was detected with the POM1 antibody whereas Tg(PrPΔ214–229) was detected with the 3F4 antibody and therefore only unspecific bands are observed for WTPrPC in this blot. Note that Tg(PrPΔ214–229) is PK resistant at the concentration widely used to define PrPSc (20 μg/ml), but compared to the prion diseased mice brain is less resistant at higher concentrations of PK. (b) Representative immunohistochemistry of cortical mouse brain sections stained with SAF84 antibody after PK digestion. Higher magnification shows accumulation of PK-resistant PrP surrounding the nucleus in Tg(PrPΔ214–229). Scale bar in (b,d) is 100 μm. (c) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of Tg(PrPΔ214–229) (grey) and of Tg(PrPΔ214–229) inoculated with brain homogenates obtained from clinically diseased Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice (black). A significant acceleration of the disease is observed (Breslow test: p* = 0.007). (d) Brains from Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice inoculated with Tg(PrPΔ214–229) brain homogenates (inoc. Tg(PrPΔ214–229)) presented very faint spongiosis (as seen with HE staining) mainly in cerebellum and striatum and no overt astro-/microgliosis (as seen with immunohistochemistry for GFAP and Iba1). Scale bar in the magnified picture is 25 μm.

However, inoculation of brain homogenates from clinically sick Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice into eight weeks old syngeneic hosts led to a significant acceleration of disease, with inoculated Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice coming down with disease at 246.75 ± 1.06 days when compared to naive Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice (270.28 ± 38.61 days, Breslow (Generalized Wilcoxon) test *p = 0.007; Fig. 6c). This acceleration of disease was not accompanied by gross neuropathological changes, although a slight vacuolation could be observed (Fig. 6d).

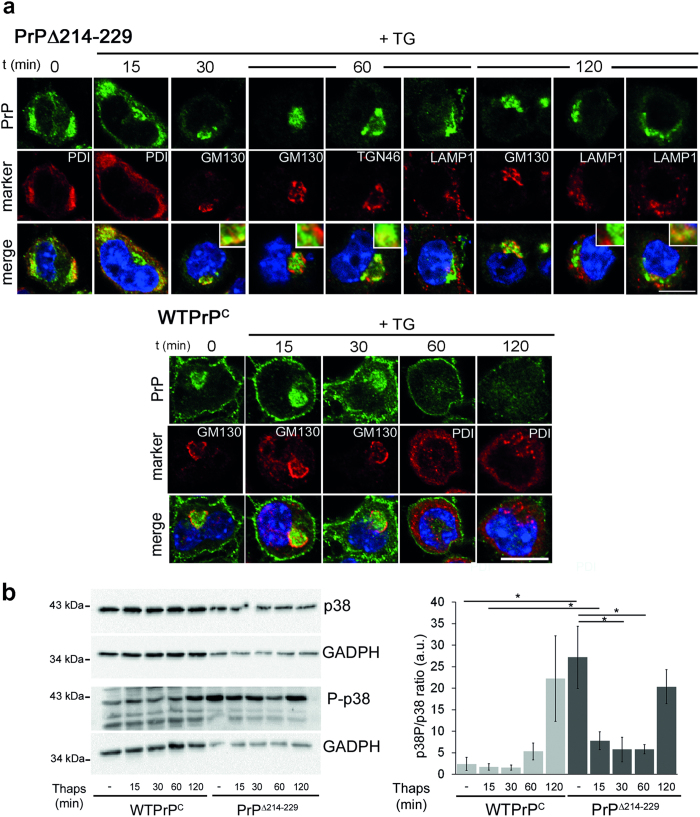

ER stress leads to PrPΔ214–229 retention in the Golgi apparatus

The fact that PrPΔ214–229 is retained in the ER but also partially detected at the plasma membrane is reminiscent of the recently described RESET pathway19. Thus, we investigated the trafficking of PrPΔ214–229 under stress conditions in N2a cells (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. PrPΔ214–229 is retained in the Golgi after Thapsigargin treatment and p38-MAPK phosphorylation is increased.

(a) N2a cells were treated with Thapsigargin (TG) for 10 min and fixed at different time points. PrPΔ214–229 (green) is found mainly in the ER (colocalizing with PDI; red) at steady-state but after 30 min it is found in the cis-Golgi (colocalizing with GM130; red) traveling to the trans-Golgi network (colocalizing with TGN46; red) after 60 min. At 120 min PrPΔ214–229 is found mainly colocalizing with GM130 again. At this time point, some degree of colocalization (inset) of PrPΔ214–229 with the lyosomal marker LAMP1 (red) could be observed. In steady-state conditions WTPrPC is mainly found in the Golgi (colocalizing with GM130; red) and at the plasma membrane. At 60 and 120 min after TG treatment the intensity of the staining is decreased and WTPrPC is found at the plasma membrane but not in Golgi anymore. Scale bar is 10 μm. (b) Representative Western blot showing that, at steady-state, there is a high level of phosphorylation of p38-MAPK in PrPΔ214–229 compared to WTPrPC that decreases between 15–60 min to increase again at 120 min (*p < 0.05).

At 0 and 15 min after Thapsigargin (TG) treatment, WTPrPC was found in the Golgi and at the plasma membrane, whereas at 60 and 120 min after TG, WTPrPC presented a diffuse intracellular and plasma membrane pattern. For PrPΔ214–229 we could observe that from 15–60 min after TG application, it moves from ER to the cis- and trans-Golgi to finally come back to the cis-Golgi after 120 min. Thus, although PrPΔ214–229 undergoes the RESET pathway under stress conditions, it does not follow a canonical RESET pathway, with almost no co-localization with the lysosomal marker LAMP-1 (Fig. 7a). As shown in Fig. 7b, PrPΔ214–229 presented with an elevated steady-state of P-p38-MAPK compared to WTPrPC (t-test, p = 0,028) that unexpectedly was significantly decreased after 30 min (t-test, p = 0,050) and 60 min (t-test, p = 0,042) of stress induction to later increase again at 120 min (Fig. 7b). Interestingly, the decrease in P-p38-MAPK coincided with the passage of PrPΔ214–229 from the ER to the Golgi.

Discussion

Here we investigated the intracellular trafficking and the associated signaling pathways of misfolded PrPC partially lacking its C-terminus (PrPΔ214–229). Our findings in neuronal cell lines show that PrPΔ214–229 is devoid of complex glycans and retained in the ER. When expressed in mice lacking endogenous PrPC, PrPΔ214–229 leads to a fatal neurological disease which can be partially rescued by genetic reintroduction of PrPC. PrPΔ214–229 does not behave as a bona fide prion yet holds PrPSc-like properties and leads to disease acceleration in syngeneic hosts. Neuronal loss in Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice is accompanied by activation of the p38-MAPK. Thus, we define a novel neurodegenerative pathway associated with defective intracellular PrP trafficking that may be relevant in prion diseases and other neurodegenerative protein misfolding disorders.

PrP is retained in the ER in a number of instances, e.g. when (i) its disulfide bond is disrupted19,35, (ii) octapeptide repetitions are inserted in the N-terminus28,36, (iii) disease causing point mutations are present at the C-terminus13,14 or (iv) GPI-anchorage is disturbed17. Consequences of ER retention are diverse and include retrotranslocation of potentially neurotoxic PrP to the cytosol15,17,36 or enhanced targeting to lysosomal degradation18.

In cultured cells, PrPΔ214–229 presents some features similar to the recently described RESET pathway19 because in steady state conditions it is mainly retained in the ER but also partially found at the plasma membrane. Under stress, PrPΔ214–229 reaches the TGN, but in contrast to the RESET pathway it cannot traffic further. RESET cargo receptors to lysosomes are only partially defined, with Tmp21 achieving the transport from the ER to the Golgi19. From our results, it might be speculated that PrPΔ214–229 is able to bind Tmp21, thus reaching the Golgi. However, due to its C-terminal deletion, the binding to other cargo receptors required for further transport to the plasma membrane might be compromised, resulting in Golgi retention. Importantly, PrPC retention in the Golgi occurs in prion infected N2a cells37, where PrPSc impairs post-Golgi trafficking. More recently, Bouybayoune et al. showed that transgenic mice expressing PrP with a C-terminal mutation (PrPD177N/M128) homologous to the human mutation causing FFI, accumulate mutant PrP in the Golgi38. These observations, together with our study, indicate that accumulation in the secretory pathway either through misfolding caused by mutations or by conversion to PrPSc could be a common mechanism for neurodegeneration related to PrP.

When expressed in mice, ER retention of PrPΔ214–229 leads to neuronal death. We therefore expected activation of signaling pathways related to ERAD39, yet we could not find evidence for this. Since the induction of such pathways is spatiotemporally controlled, it could be that the temporal resolution of our experiment was not optimal7. Most importantly, we demonstrated a clear activation of p38-MAPK that correlates with neurodegeneration. p38-MAPK (a stress-activated protein kinase, SAPK) is activated, among other signals, under ER stress conditions40 and is related to cell death in neurodegenerative diseases41. To find out if this kinase participates in the RESET pathway, we investigated p38-MAPK phosphorylation in N2a cells expressing PrPΔ214–229. We observed an elevated steady-state level of P-p38-MAPK that, to our surprise, showed a transient decrease after stress induction. Thus, one can hypothesize that it is the presence of PrPΔ214–229 in the cis-Golgi after undergoing RESET pathway that activates a p38-MAPK pathway, eventually leading to cell death. In this respect, it is worthy to note that the KDEL receptor (KDEL-R), a cis-Golgi resident that recycles chaperones containing the KDEL retrieval motif back to the ER42,43 and a key regulatory signaling receptor in ER-to-Golgi trafficking44,45,46,47, can activate p38-MAPK under ER stress further deciding the fate of the cell48,49. Although we found a clustering of PrPΔ214–229 colocalizing with the KDEL chaperones in steady-state conditions, the exact mechanism by which accumulation of PrPΔ214–229 leads to p38-MAPK phosphorylation as well as the possible participation of KDEL receptor clearly require further studies.

Neurotoxic PrP106-126 and PrPSc can activate p38-MAPK possibly by binding to plasma membrane-bound PrPC29,50. Given that PrPΔ214–229 shares some characteristics reminiscent of PrPSc, this may contribute to p38-MAPK activation in our model. Although this hypothesis cannot be ruled out, PrPΔ214–229 is present at the plasma membrane at only low amounts and reintroduction of PrPC, potentially serving as a binding and trafficking partner for PrPΔ214–229, does not aggravate but rather reduce the toxic effects. Thus, plasma membrane mediated p38-MAPK activation seems unlikely.

Partial rescue of neurotoxicity by co-expression of one Prnp allele has also been observed in transgenic mice expressing toxic N-terminal deletion mutants of PrP36. This argues in favor of a scenario where the putative functions of PrPC are partially normalized in spite of PrPΔ214–229 retention in the ER. In the model presented here, it could be that PrPC dimerizes with PrPΔ214–229 thus restoring correct trafficking and proteolytic processing51. PrPC cleavage events have key roles in physiological and neurodegenerative conditions by both, reducing PrPC at the neuronal surface and releasing soluble and neuroprotective PrP into the extracellular space52,53,54,55. Although we did not directly assess, whether PrPΔ214–229 is structurally able to undergo these cleavages, insufficient trafficking of PrPΔ214–229 to the plasma membrane (where shedding is thought to take place) is the likely reason for the absence of shedding. As a consequence, absence of neuroprotective shed PrPC might contribute to the phenotype of cells and mice expressing PrPΔ214–229.

In a number of protein misfolding disorders, inoculation of brain homogenate from an affected animal to a disease-prone host leads to acceleration of disease56. We detected the presence of PK-resistant PrPΔ214–229 and disease acceleration by inoculation into syngeneic hosts with absence of prion titers. This implies that PrPΔ214–229 can follow template-folded conversion as it has been described for other proteins in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and tauopathies.

In conclusion, we show that ER retention of a C-terminal PrP mutant leads to spontaneous neurodegeneration and neurological disease. On a molecular level, this is characterized by a trafficking defect leading to p38-MAPK activation. It will be interesting to investigate, whether activation of the p38-MAPK pathway represents a common mechanistic end stretch for other conformational dementias.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Animal experiments were approved by the Behörde für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz of the Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg (permit numbers 80/08, 38/07 and 84/13). Procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the animal facility of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf and in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

cDNA constructs

cDNA containing the mouse Prnp open reading frame with the 3F4 mAb epitope tag in pcDNA3.1 ( + )/ Zeo was a gift from M. Groschup (Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany). Mutagenesis to delete amino acids 214–229 of PrPC (GenBankTM accession number NP035300) was performed with the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies). Clones were verified by DNA sequencing.

Stably and transiently transfected cell lines and drug treatment

N2a cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium high glucose with L-gutamine, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in a 5% CO2 incubator. The generation of stable cell lines and transfections were performed as previously described57. Thapsigargin (TG; 0.1 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied for 10 min and cells were fixed at different time points. At least three independent experiments were performed for the TG treatment.

For transient transfections, SH-SY5Y cells were cultivated as described earlier58 and transfected with 1 μg DNA by using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Life Technologies).

Generation of PrPΔ214–229 mice

To insert the PrPΔ214–229 construct into the half-genomic expression vector (mPrPHG)59, a PmlI restriction site was inserted with QuickChange Lightning (Stratagene).

PrPC was excised from mPrPHG by AgeI and PmlI (Fast Digest, Fermentas; Thermo Fischer Technologies). PrPΔ214–229 was cut with AgeI and PmlI and ligated with the mPrPHG. For pronuclear injection the mPrPHG vector was cut with SalI and NotI. The pronuclear injection was performed at the Transgenic Mouse Facility (ZMNH, Hamburg). Positive animals were selected by PCR. Animals were backcrossed at least six generations to PrP0/0 in order to generate transgenic mice lacking endogenous PrPC. To generate the WTPrPC mice, littermates not expressing the transgene were backcrossed with C57Bl6 mice following a similar breeding scheme.

Primary neurons

P0–P2 mice were used. Briefly, hippocampi were dissected and collected in 10 mM glucose in PBS containing 0.5 mg/ml papain (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 μg/ml DNAse (Roche Diagnostics). After 30 min incubation at 37 °C, samples were washed with plating medium (MEM 1X (Gibco), 20 mM glucose (Sigma), 10% Horse serum (PAA Laboratories) and 3% NaHCO3 7.5% (Gibco)) and plated in 6-well plates containing Poly-L-Lys-pretreated coverslips and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 cell culture incubator. After 4 hours, the media was changed to Neurobasal A medium (Gibco) containing 2% of B27 serum, Glutamax (Gibco) and penicillin/streptomycin (PAA Laboratories). Next day, AraC (Sigma-Aldrich) was added in order to kill any proliferating cells. Half of the media was changed every 3 days. Analysis of proteolytic PrPC shedding in primary neurons was performed as described earlier24.

Western blot analysis

Confluent cells on a 6-well plate or mouse brain samples were homogenized using RIPA buffer (200 μl for cells or 10% homogenate for tissue) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (CompleteTablets EDTA-free) and phosphatase inhibitors (PhosStop) (Roche) and processed for Western blot24. For PK digestion, the experimental procedure was performed as described before24 but using different amounts of PK (10 μg/ml; 20 μg/ml; 40 μg/ml).

Confocal microscopy

Primary neurons were maintained in culture for one week before being processed for microscopy. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS containing 0.3% of bovine serum albumin (BSA). Primary antibodies were diluted in 0.3% BSA/PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT). After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies AlexaFluor 488 or 555 (Life Technologies) were incubated for 1 h at 1:500 diluted in 0.3% BSA/PBS and after washes in PBS samples were mounted with Dapi Fluoromount G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham AL). For non-permeabilizing conditions, cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated with the primary antibody for 20 min on ice. Afterwards they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and the protocol was followed as described above. Images were taken with a Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope TCS SP5 (Leica) and further analyzed with Leica Application Suite X.

PNGase F and EndoH assay

PNGase F assay was performed as described before24. For the EndoH assay (New England BioLabs), brain samples (40 μg of protein) were mixed with 10X denaturing buffer to a final volume of 20 μl and heated for 10 min at 100 °C. 6 μl of Endo H was added to 10X the reaction buffer in a final volume of 40 μl. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h.

Lipid raft isolation

Lipid rafts were isolated as previously described57.

Triton X-114 assay

The assay was performed as previously described27. Briefly, frontal cortex samples were homogenized in 10 vol. of 0.32 M sucrose in 50 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 7.4, centrifuged for 15 min at 8.000 g and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 26.000 g for 2 h. The resulting pellet was resuspended in H buffer (10 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 7.4) with the addition of 2% of precondensed Triton X-114 (Sigma-Aldrich) in a total volume of 200 μl (final concentration of 2 μg/μl). Samples were vortex mixed for 1–2 sec, let on ice for 5 min and centrifuged again at 8.880 g at 4 °C in a fixed angle rotor. The resulting pellet was washed with 0.2 ml of H buffer, centrifuged at 8.800 g for 10 min at 4 °C and the resulting pellet resuspended in 180 μl of H buffer. This was kept as the Insoluble Pellet. The supernatant was layered over a 0.3 ml of 6% sucrose cushion in T buffer (10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl) and 0.06% precondensed Triton X-114, incubated at 30 °C for 3 min and further centrifuged at 3000 g for 3 min in a swinging bucket rotor. The sucrose cushion was removed from the pellet (detergent phase) which was resuspended in 180 μl of H buffer.

The supernatant (upper aqueous phase) was mixed with 0.5%(v/v) precondensed Triton X-114, vortexed 1–2 sec, kept 5 min on ice, and further layered over a 0.3 ml 6% sucrose cushion in T buffer, incubated at 30 °C for 3 min and centrifuged again at 3000 g for 3 min in a swinging bucket rotor. The pellet was discarded and the upper phase mixed again with 2% (v/v) precondensed Triton X-114 and processed again as described in the step before but without the sucrose cushion. After the last centrifugation, the supernatant was kept as final aqueous phase. An equal amount of sample was then mixed with 4× loading buffer and 30 μl of sample was subjected to gel electrophoresis and Western blot.

Solubility assay

The assay was performed as described earlier60. Cells were washed with cold PBS, scraped off the plate and lysed with cold Buffer A (0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholic acid in PBS) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche). After 10 min incubation on ice, samples were centrifuged at 15.000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was mixed with 4× loading buffer and the pellet was washed once in PBS, incubated in 1% SDS plus benzonase (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were mixed with 4× loading buffer and boiled for 5 min at 95 °C. Equal amounts of sample were subjected to gel electrophoresis and Western blot.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were stained using a Ventana Benchmark XT (Ventana). Deparaffinised sections were incubated for 30–60 min in CC1 solution (Ventana) for antigen retrieval. Primary antibodies were diluted in 5% goat serum (Dianova), 45% Tris-buffered saline pH 7.6 (TBS) and 0, 1% Triton X-100 in antibody diluent solution (Zytomed). Sections were then incubated with primary antibody for 1 h (see supplemental list). Anti-mouse histofine Simple Stain MAX PO Universal immunoperoxidase polymer (Nichirei Biosciences) were used as secondary antibody. Detection of secondary antibodies was performed with an ultraview universal DAB detection kit from Ventana with appropriate counterstaining and sections were cover-slipped using TissueTek glove mounting media (Sakura Finetek). To allow comparability for each analysis, sections of Tg(PrPΔ214–229) mice and controls were stained in one machine run.

For PrPSc staining, samples were treated for 30 min in Peroxidase-Blocking buffer (0, 3% H2O2) and 30 min in 98% formic acid. After washing with water, samples were autoclaved for 5 min at 121 °C in citrate buffer pH 6. The protocol was then followed as described above with the additional step of PK digestion followed by incubation of SAF84 antibody.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics 22 and GraphPad Prism 5 statistic software programs were used. In order to compare differences between Kaplan-Meier survival curves, the Breslow test was used. For comparison between the groups in Western blots and neuronal countings, Student’s t-test was used. Statistical significance was considered when p-values were as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Puig, B. et al. Secretory pathway retention of mutant prion protein induces p38-MAPK activation and lethal disease in mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 24970; doi: 10.1038/srep24970 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the UMIF core facility for the help in confocal image acquisition, the Mouse Pathology Core Facility from the UKE for technical support in immunohistochemistry and the Transgenic Mouse Facility from the ZMNH for generating the transgenic mice. The hybridoma ID4B rat antibody developed by J. Thomas August was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242. POM antibodies were provided by Prof. Dr. A. Aguzzi (Universitätsspital Zürich, Switzerland). This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG): SFB877, GRK1459, TA 167/6-1 and by the Alberta Prion Research Institute (APRI): 201300024. LL is a stipend recipient of the Werner-Otto Stiftung.

Footnotes

Author Contributions B.P. and M.G. designed the study; B.P., H.C.A., S.U., L.L., K.C., S.K. and C.A.M. performed the experiments; B.P., M.G., J.T., H.W. and H.C.A. analyzed the data and interpreted the results; B.P., M.G. and H.C.A. wrote the paper.

References

- Anelli T. & Sitia R. Protein quality control in the early secretory pathway. EMBO J 27, 315–327 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meusser B., Hirsch C., Jarosch E. & Sommer T. ERAD: the long road to destruction. Nat Cell Biol 7, 766–772 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsukasa K., Huyer G., Michaelis S. & Brodsky J. L. Dissecting the ER-associated degradation of a misfolded polytopic membrane protein. Cell 132, 101–112 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P. & Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334, 1081–1086 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski D. T. & Hegde R. S. Regulation of basal cellular physiology by the homeostatic unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol 189 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C. & Mollereau B. Disturbance of endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 233–249 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipanski A. et al. A Novel Interaction Between Ageing and ER Overload in a Protein Conformational Dementia. Genetics 193(3), 865–876 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M. et al. ER stress signaling and neurodegeneration: At the intersection between Alzheimer’s disease and Prion-related disorders. Virus Res 207, 69–75 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S. & Riezman H. Sorting GPI-anchored proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5, 110–120 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesebro B. Introduction to the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies or prion diseases. Br Med Bull 66, 1–20 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner S. B., Scott M. R., DeArmond S. J. & Cohen F. E. Prion protein biology. Cell 93, 337–348 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguzzi A. & Polymenidou M. Mammalian prion biology: one century of evolving concepts. Cell 116, 313–327 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C. A. & Soto C. Stressing out the ER: a role of the unfolded protein response in prion-related disorders. Curr Mol Med 6, 37–43 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs G. G. et al. Mutations of the prion protein gene phenotypic spectrum. J Neurol 249, 1567–1582 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. & Lindquist S. Wild-type PrP and a mutant associated with prion disease are subject to retrograde transport and proteasome degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 14955–14960 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. & Lindquist S. Conversion of PrP to a self-perpetuating PrPSc-like conformation in the cytosol. Science 298, 1785–1788 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok A. & Hegde R. S. Retrotranslocation of prion proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum by preventing GPI signal transamidation. Mol Biol Cell 19, 3463–3476 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok A. & Hegde R. S. Selective processing and metabolism of disease-causing mutant prion proteins. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000479 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpute-Krishnan P. et al. ER stress-induced clearance of misfolded GPI-anchored proteins via the secretory pathway. Cell 158, 522–533 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto T. et al. Heritable disorder resembling neuronal storage disease in mice expressing prion protein with deletion of an alpha-helix. Nat Med 3, 750–755 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley A. R., Watt N. T., Taylor D. R., Perera W. S. & Hooper N. M. alpha-cleavage of the prion protein occurs in a late compartment of the secretory pathway and is independent of lipid rafts. Mol Cell Neurosci 40, 242–248 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt D. R., Rogers M., Stahl N., Telling G. & Prusiner S. B. Release of the cellular prion protein from cultured cells after loss of its glycoinositol phospholipid anchor. Glycobiology 3, 319–329 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. R. et al. Role of ADAMs in the ectodomain shedding and conformational conversion of the prion protein. J Biol Chem 284, 22590–22600 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmeppen H. C. et al. Lack of a-disintegrin-and-metalloproteinase ADAM10 leads to intracellular accumulation and loss of shedding of the cellular prion protein in vivo. Mol Neurodegener 6, 36 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmeppen H. C. et al. Proteolytic processing of the prion protein in health and disease. Am J Neurodegener Dis 1, 15–31 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostapchenko V. G. et al. The prion protein ligand, stress-inducible phosphoprotein 1, regulates amyloid-beta oligomer toxicity. J Neurosci 33, 16552–16564 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper N. M. & Bashir A. Glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins can be distinguished from transmembrane polypeptide-anchored proteins by differential solubilization and temperature-induced phase separation in Triton X-114. Biochem J 280(Pt 3), 745–751 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova L., Barmada S., Kummer T. & Harris D. A. Mutant prion proteins are partially retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 276, 42409–42421 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradines E. et al. Pathogenic prions deviate PrP(C) signaling in neuronal cells and impair A-beta clearance. Cell Death Dis 4, e456 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. P. et al. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in hamster brains infected with 263K scrapie agent. J Neurochem 95, 584–593 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig B., Altmeppen H. & Glatzel M. The GPI-anchoring of PrP: Implications in sorting and pathogenesis. Prion 8, 11–18 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate C., Tayebi M. & Williams A. Sequestration of free cholesterol in cell membranes by prions correlates with cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activation. BMC biology 6, 8 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resenberger U. K. et al. The cellular prion protein mediates neurotoxic signalling of beta-sheet-rich conformers independent of prion replication. EMBO J 30, 2057–2070 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasini E. et al. A mutant prion protein sensitizes neurons to glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. J Neurosci 33, 2408–2418 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrett C. A. et al. Changing the solvent accessibility of the prion protein disulfide bond markedly influences its trafficking and effect on cell function. Biochem J 428, 169–182 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasini E., Turnbaugh J. A., Unterberger U. & Harris D. A. Prion protein at the crossroads of physiology and disease. Trends Neurosci 35, 92–103 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama K. et al. Prions disturb post-Golgi trafficking of membrane proteins. Nat Commun 4, 1846 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouybayoune I. et al. Transgenic fatal familial insomnia mice indicate prion infectivity-independent mechanisms of pathogenesis and phenotypic expression of disease. PLoS Pathog 11, e1004796 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak S. J. & Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev 86, 1133–1149 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S. J. & LoGrasso P. Signalling for survival and death in neurones: the role of stress-activated kinases, JNK and p38. Cell Signal 13, 299–310 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I. et al. Current advances on different kinases involved in tau phosphorylation, and implications in Alzheimer’s disease and tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res 2, 3–18 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. Recycling of proteins between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol 3, 585–591 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoe T. et al. The KDEL receptor, ERD2, regulates intracellular traffic by recruiting a GTPase-activating protein for ARF1. EMBO J 16, 7305–7316 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K. et al. The KDEL receptor mediates a retrieval mechanism that contributes to quality control at the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 20, 3082–3091 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvirenti T. et al. A traffic-activated Golgi-based signalling circuit coordinates the secretory pathway. Nat Cell Biol 10, 912–922 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotta M. et al. The KDEL receptor couples to Galphaq/11 to activate Src kinases and regulate transport through the Golgi. EMBO J 31, 2869–2881 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancino J. et al. Control systems of membrane transport at the interface between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi. Dev Cell 30, 280–294 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K. et al. The KDEL receptor modulates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response through mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. J Biol Chem 278, 34525–34532 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitani M. & Sallese M. The KDEL receptor: new functions for an old protein. FEBS Lett 583, 3863–3871 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietri M. et al. Overstimulation of PrPC signaling pathways by prion peptide 106-126 causes oxidative injury of bioaminergic neuronal cells. J Biol Chem 281, 28470–28479 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roucou X. Regulation of PrP(C) signaling and processing by dimerization. Front Cell Dev Biol 2, 57 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaani J., Prusiner S. B., Diacovo J., Baekkeskov S. & Legname G. Recombinant prion protein induces rapid polarization and development of synapses in embryonic rat hippocampal neurons in vitro. J Neurochem 95, 1373–1386 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmeppen H. C. et al. The sheddase ADAM10 is a potent modulator of prion disease. eLife 4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatzel M. et al. Shedding light on prion disease. Prion 9, 244–256 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. L., Choi J. K., Surewicz K. & Surewicz W. K. Soluble Prion Protein Binds Isolated Low Molecular Weight Amyloid-beta Oligomers Causing Cytotoxicity Inhibition. ACS chemical neuroscience 6, 1972–1980 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M. & Walker L. C. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 501, 45–51 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig B. et al. N-Glycans and Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchor Act on Polarized Sorting of Mouse PrP in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney Cells. PLoS ONE 6, e24624 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winklhofer K. F. et al. Determinants of the in vivo Folding of the Prion Protein. A bipartite function of helix 1 in folding and aggregation. J Biol Chem 278, 14961–14970 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. et al. Prion protein (PrP) with amino-proximal deletions restoring susceptibility of PrP knockout mice to scrapie. EMBO J 15, 1255–1264 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatzelt J., Prusiner S. B. & Welch W. J. Chemical chaperones interfere with the formation of scrapie prion protein. EMBO J 15, 6363–6373 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.