Abstract

Objective

The aim of this report is to provide insight into real-world healthcare resource use (HCRU) during the critical management of patients surviving acute coronary syndromes (ACS), using data from EPICOR (long-tErm follow-up of antithrombotic management Patterns In acute CORonary syndrome patients) (NCT01171404).

Methods

EPICOR was a prospective, multinational, observational study that enrolled 10 568 ACS survivors from 555 hospitals in 20 countries in Europe and Latin America, between September 2010 and March 2011. HCRU was evaluated in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS), with or without a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Multivariable analysis was performed to determine factors that affected resource use.

Results

Before hospitalisation, more patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS had their first ECG (44.1% vs 36.4%, p<0.0001) and received antithrombotic medication (26.6% vs 15.2%, p<0.0001). Patients with NSTE-ACS with prior CVD were less likely than those without to be catheterised (73.1% vs 82.8%, p<0.0001). More patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS had percutaneous coronary intervention (77.1% vs 54.9%, p<0.0001), but fewer underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (1.2% vs 3.7%, p<0.0001). Multivariable analysis showed that resource use, including length of hospital stay and coronary revascularisation, was significantly influenced by multiple factors, including ACS type, site characteristics and region (all p≤0.05).

Conclusions

In this large-scale, real-life study, findings were generally in line with clinical logic, although site characteristics and region still significantly affected resource use. Moreover, and unexpectedly, resource use tended to be slightly higher in patients without a history of CVD.

Trial registration number

NCT01171404 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Previous studies have shown variability in the real-world management of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), both within and between countries, and evidence-based management is often suboptimal. In general, patients with a history of cardiovascular disease are reported to receive more intensive care.

What does this study add?

This large-scale observational study provides real-world information on in-hospital healthcare resource use differences in patients with ACS across Europe and Latin America, including by diagnosis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction versus non-ST-segment elevation ACS, and suggests that resource use is, unexpectedly, higher in patients without a history of cardiovascular disease. Differences in resource use between settings and regions are still significant, and point to supply-side-driven rather than need-driven medical consumption.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Increased awareness of variability in ACS management may encourage closer adherence to treatment guidelines, and highlight the need for efficient hospital networks, with patient flow and treatment implemented as a function of patient needs.

Introduction

In 2008, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) was responsible for around 7.3 million deaths worldwide,1 and, in 2010, was the top-ranked cause of disability-adjusted life years.2 The majority of IHD deaths are due to acute coronary syndromes (ACS), which include ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS, comprising non-STEMI (NSTEMI) and unstable angina).

Optimal management of ACS is crucial in the prevention of later complications.3–6 Nevertheless, there is still large variability in the real-world management of patients with ACS, both within and between countries.7–9 Evidence-based management is often suboptimal,9 10 and the risk of experiencing a new cardiovascular (CV) event remains high.11 12 Reasons for variability in healthcare resource use (HCRU) in patients with ACS may be related to differences in availability of catheterisation laboratories and/or cardiac surgery facilities, or patient-related factors, such as insurance coverage,13 age14 and sex.15 Opportunities therefore exist to improve the management of patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS.16 17

Prehospital resource use and costs associated with ACS are poorly documented in the literature. The aim of the present analysis is to better understand (from the perspective of healthcare payers) the variation in prehospital and in-hospital resource use after STEMI and NSTE-ACS, using acute phase data from the EPICOR (long-tErm follow-up of antithrombotic management Patterns In acute CORonary syndrome patients) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01171404).

Methods

Overall study design

EPICOR is a prospective, multinational, observational study of adults (≥18 years) surviving hospitalisation for an ACS within 24 h of symptom onset, designed to describe antithrombotic management patterns during the index hospitalisation and after discharge. The rationale and design of EPICOR have been published previously.18 Briefly, the aim was to record real-world clinical management of ACS survivors in the acute phase (prehospital and in-hospital) and during a 2-year follow-up period, as well as short-term and long-term clinical outcomes, in a wide range of hospitals and countries in four predefined regions: Northern Europe, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe and Latin America. There were three potential opportunities for enrolment in EPICOR: (1) non-transferred patients (discharged from the hospital to which they were admitted, ie, hospital 1); (2) transferred-in patients (discharged from the hospital to which they were transferred from elsewhere, ie, hospital 2) and (3) transferred-out patients (admitted to hospital 1, having been transferred out to hospital 2, and then transferred back to and discharged from hospital 1). Patients who were transferred to a non-participating hospital and not transferred back again were therefore not included in the study. Detailed information on transfer patterns in EPICOR have been published elsewhere.19

Acute phase resource use analysis

The specific aim of the present study is to evaluate, from the healthcare payer perspective, HCRU during the acute ACS phase (prehospital and in-hospital data). This was a pre-specified secondary objective of EPICOR. Data collection during this phase was prospectively carried out by the investigator at each site, using electronic case report forms. The resource analysis is given below.

Prehospital resources (from symptom onset to hospital admission): ECG, CV medication received (fibrinolytics, antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants) and the duration of ambulance transfer between hospitals for those patients who were transferred. Transport to the initial hospital was not recorded.

In-hospital resources (including all those in-patients transferred between hospitals): laboratory tests and investigations (white cell count, creatinine, blood glucose, haemoglobin, haematocrit, cardiac markers (CK-MB and troponins)); diagnostic procedures (ECG, echocardiography, treadmill, stress echocardiography, nuclear imaging, MRI, angiographic CT scan); therapeutic procedures (resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, intra-aortic balloon pumping, temporary or permanent pacemaker, implantable cardiac defibrillator, cardiac resynchronisation therapy); interventions (any cardiac catheterisation, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)/stents, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or other cardiac surgery); number (%) of patients receiving CV medication (fibrinolytics, antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants); and length of hospital stay (LOS) (overall and by hospital transfer status).

HCRU was summarised by diagnosis of STEMI or NSTE-ACS, and by presence or absence of a history of CV disease (CVD), to try to understand whether this had an impact on use of resources. History of CVD included any of the following: prior IHD (myocardial infarction, PCI, CABG, chronic angina), coronary angiogram diagnostic for coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure, atrial fibrillation, transient ischaemic attack/stroke or peripheral vascular disease. Related p values comparing the two diagnostic groups and history of CVD yes/no for each diagnostic group were produced using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Student t test for continuous variables.

Multivariable analysis was applied to investigate the drivers of the intensity of resource use. The four possible outcome variables of interest determined by the EPICOR Executive Committee were: (1) duration of hospital stay (modelled as log(days)); (2) in-hospital coronary revascularisation (PCI or CABG; yes/no); (3) any in-hospital therapeutic procedure (resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, intra-aortic balloon pumping, temporary/permanent pacemaker, implantable cardiac defibrillator, cardiac resynchronisation therapy; yes/no) and (4) any fibrinolytic use.

A separate forward stepwise selection process considering the identified set of candidate variables was performed for each of the four outcome variables individually (linear regression model for duration of stay and logistic regression model for other outcomes). The generated models were inspected, compared and refined to incorporate agreed changes to derive a set of final individual models. The selected variables for the four models were then reconciled and a set of common models was fitted for each of the outcomes, including all of the variables that were previously selected for any of the outcomes. The individual final models were then compared with the common models to ensure that no substantial changes to the general results and conclusions were observed.

Results

Patients

Between 1 September 2010 and 31 March 2011, a total of 10 568 consecutive patients surviving an ACS were enrolled in EPICOR from 555 hospitals in 20 countries in the four predefined regions. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. Ninety-three patients were excluded from the present analysis because there was no information on a history of CVD.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics18

| STEMI (n=4943) | NSTE-ACS (n=5625) | Total (n=10 568) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 59.4 (12.1) | 63.8 (12.1) | 61.8 (12.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 3924 (79.4) | 3996 (71.0) | 7920 (74.9) |

| Female | 1019 (20.6) | 1629 (29.0) | 2648 (25.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 4026 (81.4) | 4784 (85.0) | 8810 (83.4) |

| Black | 19 (0.4) | 38 (0.7) | 57 (0.5) |

| Oriental | 19 (0.4) | 24 (0.4) | 43 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 46 (0.9) | 60 (1.1) | 106 (1.0) |

| Other | 654 (13.2) | 544 (9.7) | 1198 (11.3) |

| BMI, mean (SD)* | 27.5 (4.3) | 28.0 (4.7) | 27.7 (4.5) |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| Northern Europe | 1608 (32.5) | 2174 (38.6) | 3782 (35.8) |

| Southern Europe | 1124 (22.7) | 1213 (21.6) | 2337 (22.1) |

| Eastern Europe | 1145 (23.2) | 1235 (22.0) | 2380 (22.5) |

| Latin America | 1066 (21.6) | 1003 (17.8) | 2069 (19.6) |

| Presence of CV risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 2409 (48.7) | 3709 (65.9) | 6118 (57.9) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 1940 (39.2) | 2954 (52.5) | 4894 (46.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 893 (18.1) | 1511 (26.9) | 2404 (22.7) |

| Family history of CAD | 1451 (29.4) | 1728 (30.7) | 3179 (30.1) |

| Current smoking | 2204 (44.6) | 1621 (28.8) | 3825 (36.2) |

| Obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2) | 965 (19.5) | 1295 (23.0) | 2260 (21.4) |

| Any previous CVD, n (%) | 1042 (21.1) | 2672 (47.5) | 3714 (35.1) |

| Prior MI | 498 (10.1) | 1462 (26.0) | 1960 (18.5) |

| Prior PCI | 388 (7.8) | 1170 (20.8) | 1558 (14.7) |

| Prior CABG | 84 (1.7) | 534 (9.5) | 618 (5.8) |

| Coronary angiogram diagnostic for CAD | 425 (8.6) | 1475 (26.2) | 1900 (18.0) |

| Chronic angina | 277 (5.6) | 956 (17.0) | 1233 (11.7) |

| Heart failure | 88 (1.8) | 419 (7.4) | 507 (4.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 129 (2.6) | 368 (6.5) | 497 (4.7) |

| TIA/stroke | 150 (3.0) | 365 (6.5) | 515 (4.9) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 145 (2.9) | 384 (6.8) | 529 (5.0) |

| Chronic CV medication in the 3 months prior to index event, n (%) | |||

| Any antiplatelet agent | 1024 (20.7) | 2640 (46.9) | 3664 (34.7) |

| Aspirin | 972 (19.7) | 2476 (44.0) | 3448 (32.6) |

| Clopidogrel | 221 (4.5) | 848 (15.1) | 1069 (10.1) |

| Prasugrel | 13 (0.3) | 16 (0.3) | 29 (0.3) |

| Anticoagulants | 99 (2.0) | 300 (5.3) | 399 (3.8) |

| β-blockers | 833 (16.9) | 2222 (39.5) | 3055 (28.9) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 1289 (26.1) | 2526 (44.9) | 3815 (36.1) |

| Statins | 900 (18.2) | 2241 (39.8) | 3141 (29.7) |

| Non-statin lipid-lowering agents | 133 (2.7) | 288 (5.1) | 421 (4.0) |

| Aldosterone inhibitors | 50 (1.0) | 174 (3.1) | 224 (2.1) |

| Loop diuretics | 161 (3.3) | 526 (9.4) | 687 (6.5) |

| Non-loop diuretics | 237 (4.8) | 485 (8.6) | 722 (6.8) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 415 (8.4) | 875 (15.6) | 1290 (12.2) |

Reprinted with permission from Bueno et al.18

*BMI was not available for 694 patients with STEMI and 866 patients with NSTE-ACS.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, CV disease; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation MI; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Prehospital resource use

Table 2 shows HCRU during the prehospital phase in terms of ECG use, duration of transfer and CV medication. Prehospital ECG was more frequent in patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS (44.1% vs 36.4%, p<0.0001), but there was no difference between those with or without a history of CVD. Hospital transfers were more frequent in patients with STEMI as well as in those without prior CVD (p≤0.001 in each case). Significantly more patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS received prehospital fibrinolytics, antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants (total 26.6% vs 15.2%, p<0.0001 in each case) (table 2 and online supplementary table S1). Within both the STEMI and NSTE-ACS populations, CV medication was used in a slightly smaller percentage of patients with than without a history of CVD (table 2).

Table 2.

Prehospital HCRU in patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS with or without a history of CVD

| STEMI |

NSTE-ACS |

Overall p value for STEMI vs NSTE-ACS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource use item | History of CVD (n=1042) | No history of CVD (n=3857) | All (n=4899) | p Value for CVD vs no CVD | History of CVD (n=2672) | No history of CVD (n=2904) | All (n=5576) | p Value for CVD vs no CVD | |

| ECG* | 444 (44.7) | 1717 (44.5) | 2161 (44.1) | 0.91 | 973 (36.4) | 1058 (36.4) | 2031 (36.4) | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Any prehospital CV medication | 261 (25.0) | 1043 (27.0) | 1304 (26.6) | 0.20 | 376 (14.1) | 469 (16.2) | 845 (15.2) | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Any fibrinolytic | 17 (1.6) | 90 (2.3) | 107 (2.2) | 0.17 | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Any antiplatelet agent | 256 (24.6) | 1026 (26.6) | 1282 (26.2) | 0.19 | 358 (13.4) | 465 (16.0) | 823 (14.8) | 0.01 | <0.0001 |

| Any anticoagulant | 131 (12.6) | 571 (14.8) | 702 (14.3) | 0.07 | 113 (4.2) | 139 (4.8) | 252 (4.5) | 0.32 | <0.0001 |

| Ambulance transfer, n (%)† | 352 (33.7) | 1519 (39.4) | 1871 (38.2) | 0.001 | 735 (27.5) | 1016 (35.0) | 1751 (31.4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Duration, minutes; mean (SD) | 72.0 (86.8) | 64.6 (73.8) | 66.0 (76.4) | 0.14 | 63.5 (85.2) | 65.4 (75.5) | 64.6 (79.7) | 0.63 | 0.59 |

| Median (range) | 47.5 (8–950) | 45 (1–960) | 45 (1–960) | … | 40 (5–900) | 45 (5–999) | 45 (5–999) | … | … |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

*ECG data were unavailable for 254 patients.

†Transport between hospitals, not transport to initial hospital.

CV, cardiovascular; CVD, CV disease; HCRU, healthcare resource use; NSTE-ACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

openhrt-2015-000347supp_tables.pdf (273.6KB, pdf)

In-hospital resource use

Table 3 shows in-hospital HCRU for any components for which there were statistically significant differences between patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS, or between those with and without a history of CVD in each diagnostic group.

Table 3.

In-hospital HCRU with any statistically significant differences in use between patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS with or without a history of CVD*

| Resource use item | STEMI |

NSTE-ACS |

Overall p value for STEMI vs NSTE-ACS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of CVD (n=1042) | No history of CVD (n=3857) | All (n=4899) | p Value for CVD vs no CVD | History of CVD (n=2672) | No history of CVD (n=2904) | All (n=5576) | p Value for CVD vs no CVD | ||

| Laboratory tests and investigations | |||||||||

| On admission | |||||||||

| Blood glucose | 904 (86.8) | 3379 (87.6) | 4283 (87.4) | 0.46 | 2267 (84.8) | 2554 (87.9) | 4821 (86.5) | <0.001 | 0.14 |

| Haematocrit | 889 (85.3) | 3359 (87.1) | 4248 (86.7) | 0.14 | 2274 (85.1) | 2452 (84.4) | 4726 (84.8) | 0.49 | <0.01 |

| During hospitalisation | |||||||||

| Creatinine | 921 (88.4) | 3436 (89.1) | 4357 (88.9) | 0.53 | 2330 (87.2) | 2524 (86.9) | 4854 (87.1) | 0.75 | <0.01 |

| Diagnostic procedures | |||||||||

| Echocardiography | 852 (81.8) | 3250 (84.3) | 4102 (83.7) | 0.053 | 1957 (73.2) | 2238 (77.1) | 4195 (75.2) | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Non-invasive testing | |||||||||

| Treadmill | 29 (2.8) | 184 (4.8) | 213 (4.3) | <0.01 | 140 (5.2) | 198 (6.8) | 338 (6.1) | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

| Nuclear imaging | 36 (3.5) | 93 (2.4) | 129 (2.6) | 0.06 | 69 (2.6) | 38 (1.3) | 107 (1.9) | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| MRI | 11 (1.1) | 74 (1.9) | 85 (1.7) | 0.06 | 24 (0.9) | 33 (1.1) | 57 (1.0) | 0.38 | <0.01 |

| CT angiography | 10 (1.0) | 27 (0.7) | 37 (0.8) | 0.39 | 40 (1.5) | 32 (1.1) | 72 (1.3) | 0.19 | <0.01 |

| Therapeutic procedures | |||||||||

| Resuscitation | 40 (3.8) | 167 (4.3) | 207 (4.2) | 0.49 | 33 (1.2) | 40 (1.4) | 73 (1.3) | 0.64 | <0.0001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%)† | 18 (1.7) | 92 (2.4) | 110 (2.2) | 0.20 | 28 (1.0) | 34 (1.2) | 62 (1.1) | 0.66 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of ventilation, days; mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.6) | 3.4 (3.2) | 3.2 (3.0) | 0.03 | 2.3 (3.0) | 2.8 (4.5) | 2.6 (3.9) | 0.63 | 0.30 |

| Median (range) | 1.5 (1–6) | 2 (1–16) | 2 (1–16) | … | 1 (1–12) | 1 (1–26) | 1 (1–26) | … | … |

| Intra-aortic balloon pumping | 18 (1.7) | 69 (1.8) | 87 (1.8) | 0.89 | 16 (0.6) | 20 (0.7) | 36 (0.6) | 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| Temporary pacemaker | 33 (3.2) | 97 (2.5) | 130 (2.7) | 0.25 | 22 (0.8) | 22 (0.8) | 44 (0.8) | 0.78 | <0.0001 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 9 (0.9) | 20 (0.5) | 29 (0.6) | 0.20 | 54 (2.0) | 12 (0.4) | 66 (1.2) | <0.0001 | <0.01 |

| Implantable cardiac defibrillator | 8 (0.8) | 17 (0.4) | 25 (0.5) | 0.19 | 24 (0.9) | 8 (0.3) | 32 (0.6) | <0.01 | 0.66 |

| Coronary intervention | |||||||||

| Any cardiac catheterisation | 878 (84.3) | 3338 (86.5) | 4216 (86.1) | 0.06 | 1952 (73.1) | 2404 (82.8) | 4356 (78.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Any PCI | 771 (74.0) | 3008 (78.0) | 3779 (77.1) | <0.01 | 1284 (48.1) | 1776 (61.2) | 3060 (54.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PCI + ≥1 stent (any) | 698 (67.0) | 2924 (75.8) | 3622 (73.9) | <0.0001 | 1182 (44.2) | 1728 (59.5) | 2910 (52.2) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PCI + ≥1 BMS | 456 (43.8) | 1871 (48.5) | 2327 (47.5) | <0.01 | 583 (21.8) | 900 (31.0) | 1483 (26.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PCI + ≥1 DES | 265 (25.4) | 1175 (30.5) | 1440 (29.4) | <0.01 | 667 (25.0) | 903 (31.1) | 1570 (28.2) | <0.0001 | 0.16 |

| CABG | 10 (1.0) | 48 (1.2) | 58 (1.2) | 0.45 | 93 (3.4) | 114 (3.9) | 207 (3.7) | 0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Antithrombotic medication‡ | |||||||||

| At least one fibrinolytic | 151 (14.5) | 610 (15.8) | 761 (15.5) | 0.30 | 7 (0.3) | 17 (0.6) | 24 (0.4) | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| At least one antiplatelet agent | 1041 (99.9) | 3857 (100) | 4898 (100) | 0.05 | 2656 (99.4) | 2895 (99.7) | 5551 (99.6) | 0.11 | <0.0001 |

| Total LOS, days | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (6.9) | 7.7 (6.0) | 7.8 (6.2) | <0.01 | 8.1 (5.8) | 7.2 (5.3) | 7.7 (5.6) | <0.0001 | 0.20 |

| Median (range) | 7 (1–97) | 6 (1–157) | 6 (1–157) | … | 6 (1–49) | 6 (1–62) | 6 (1–62) | … | … |

| Flow types (%)§ | |||||||||

| No transfer from hospital 1 | 690 (66.2) | 2338 (60.6) | 3028 (61.8) | <0.01 | 1937 (72.5) | 1888 (65.0) | 3825 (68.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Transfer from hospital 1 to 2 | 262 (25.1) | 1131 (29.3) | 1393 (28.4) | … | 382 (14.2) | 531 (18.3) | 913 (16.4) | … | … |

| Transfer from hospital 1 to 2 to 1 | 90 (8.6) | 388 (10.1) | 478 (9.8) | … | 353 (13.2) | 485 (16.7) | 838 (15.0) | … | … |

| LOS by transfer group, days | |||||||||

| No transfer from hospital 1 | |||||||||

| n (%) | 690 (66.2) | 2338¶ (60.6) | 3028 (61.8) | … | 1937 (72.5) | 1888 (65.0) | 3825 (68.6) | … | … |

| Mean LOS (SD) | 7.9 (4.9) | 7.4 (5.9) | 7.5 (5.7) | 0.02 | 7.4 (5.1) | 6.6 (4.6) | 7.0 (4.9) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Median LOS (range) | 7 (1–41) | 6 (1–157) | 6 (1–157) | … | 6 (1–47) | 6 (1–62) | 6 (1–62) | … | … |

| Transfer from hospital 1 to 2 | |||||||||

| n (%) | 262 (25.1) | 1131 (29.3) | 1393 (28.4) | … | 382 (14.2) | 531 (18.3) | 913 (16.4) | … | … |

| Mean LOS (SD) | 9.5 (10.7) | 8.1 (5.7) | 8.4 (7.0) | 0.05 | 10.0 (7.0) | 8.1 (6.3) | 8.9 (6.7) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| Median LOS (range) | 7 (1–97) | 6 (1–76) | 7 (1–97) | … | 8 (3–49) | 7 (2–59) | 7 (2–59) | … | … |

| Transfer from hospital 1 to 2 to 1 | |||||||||

| n (%) | 90 (8.6) | 388 (10.1) | 478 (9.8) | … | 353 (13.2) | 485 (16.7) | 838 (15.0) | … | … |

| Mean LOS (SD) | 7.9 (5.0) | 8.2 (7.3) | 8.1 (6.9) | 0.74 | 10.1 (7.0) | 8.7 (5.9) | 9.3 (6.4) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Median LOS (range) | 6 (2–31) | 6.5 (1–95) | 6 (1–95) | … | 8 (1–46) | 7 (2–46) | 7 (1–46) | … | … |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

*Includes resource use in all hospitals, if patients were transferred.

†Duration of mechanical ventilation data not available for 12 patients.

‡Data provided for in-hospital antithrombotic medication administered to ≥1% of patients with STEMI or NSTE-ACS.

§p Values for flow type compare the three flow types together.

¶LOS data not available for 1520 patients with STEMI and no prior CVD.

BMS, bare-metal stent; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DES, drug-eluting stent; HCRU, healthcare resource use; LOS, length of hospital stay; NSTE-ACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

There were minimal differences between the CVD history groups in terms of most diagnostic procedures, although patients with no CVD history were more likely to undergo echocardiography and treadmill testing. Significantly more patients with STEMI underwent echocardiography, nuclear imaging and MRI, and significantly more patients with NSTE-ACS underwent treadmill testing and angiographic CT scan. Both cardiac catheterisation and PCI were significantly more likely to be performed in patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS (86.1% vs 78.1% and 77.1% vs 54.9%, respectively; both p<0.0001) and, in patients with NSTE-ACS, less likely in those with a history of CVD than those without (73.1% vs 82.8% and 48.1% vs 61.2%, respectively; both p<0.0001). More patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS received at least one stent and at least one bare-metal stent (p<0.0001 in each case), but use of drug-eluting stents was comparable in both groups. Use of any stent was significantly less frequent in those with a history of CVD than in those without. In contrast, patients with STEMI were less likely to undergo CABG (1.2% vs 3.7%, p<0.0001), with no difference between those with or without a history of CVD. The majority of patients across the four groups underwent standard laboratory tests on admission and were evaluated for cardiac markers during hospitalisation. The percentage of patients receiving each investigation was generally similar in all groups. Significantly more patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS underwent resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, intra-aortic balloon pumping and placement of a temporary pacemaker (p<0.0001 in each case), but there were no differences between those with or without prior CVD in each group. In contrast, patients with NSTE-ACS were more likely to receive a permanent pacemaker, particularly patients with a history of CVD (p<0.0001 compared with those without).

Total LOS, including days in the second hospital for those who were transferred, ranged from 1 to 157 days, with an average of 7.2–8.3 days in patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS, respectively, and a median of 6–7 days, and was significantly longer in patients with than in those without a history of CVD, particularly in the NSTE-ACS group (table 3). Among patients who were transferred between hospitals, mean overall LOS was longer in patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS compared with those not transferred.

Nearly all patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS received an antiplatelet agent in hospital (table 3), and almost 80% of patients in each diagnostic group received an anticoagulant (online supplementary table S2). Details of in-hospital CV medication by drug type are shown in the online supplementary table S2. Use of all three classes of medication was generally lower in patients with a history of CVD than in those without. Overall, use of the newer anticoagulant agents was low, with fondaparinux being the most frequently used, particularly in patients with NSTE-ACS.

Multivariable analyses

Duration of hospital stay

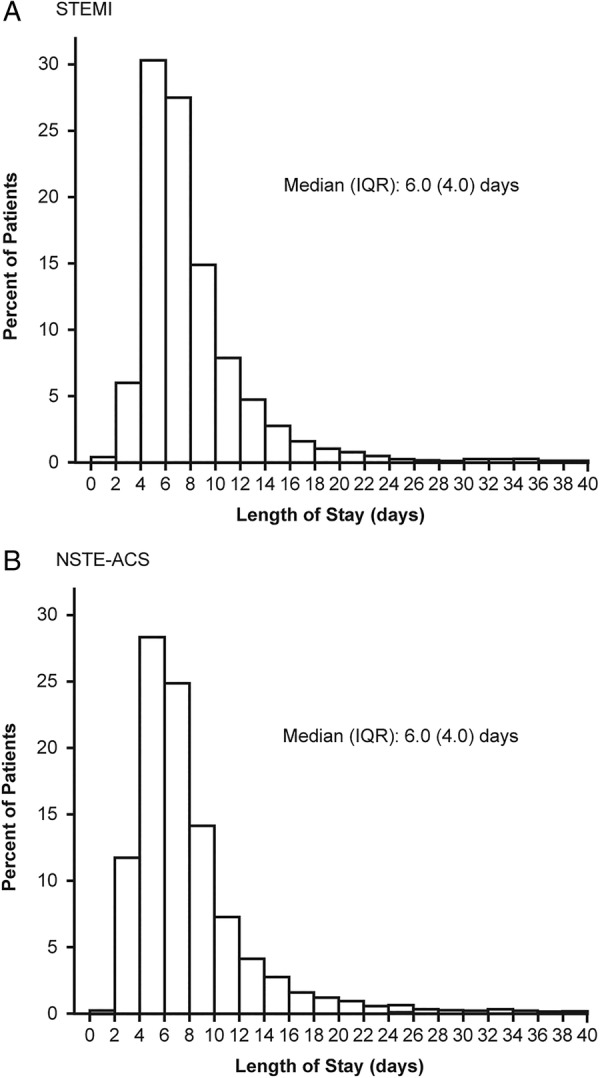

Figure 1 shows the distribution of LOS in patients with (1) STEMI and (2) NSTE-ACS. Many of the proposed candidate variables were found to be significantly associated with LOS (see online supplementary table S3). Those most likely to be associated with increased stay (all p<0.0001) were ACS type (STEMI vs NSTE-ACS), region (Latin America vs Northern Europe; Southern Europe vs Northern Europe), older age, presence of diabetes, previous peripheral vascular disease, previous non-CVD, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <30%, or ‘severely reduced’, and Killip Class. Presence of hypertension (p<0.001) and prior CAD (p<0.001) were also strong predictors of increased LOS. Variables most likely to be associated with shorter LOS were presence of catheterisation laboratory facilities (p<0.0001), centre type (university general hospital and other type of hospital/clinic, both p<0.0001 vs regional/community/rural hospital, and non-university hospital vs regional/community/rural hospital, p<0.001) and chronic CV medication (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of total length of hospital stay: patients with (A) ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and (B) non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS).

In-hospital coronary revascularisation

There were also many variables associated with either increased or decreased likelihood of coronary revascularisation (see online supplementary table S4). The variable with the strongest positive association was the presence of catheterisation laboratory facilities, followed by diagnosis of STEMI (p<0.0001 in each case). Other variables strongly associated with increased likelihood of revascularisation (all p≤0.001) were male gender, family history of CAD and time from symptom onset to hospital admission <1 h. Variables strongly associated with decreased likelihood of coronary intervention (all p≤0.001) were region (Latin America, Eastern Europe and Southern Europe vs Northern Europe), prior cardiac disease, atrial fibrillation, centre type (non-university general hospital vs regional/community/rural hospital, and non-severe dependence vs none or unknown degree of dependence). A full list of the variables analysed is shown in the online supplementary tables S5–S7.

Any in-hospital therapeutic procedure

The variables most strongly associated with increased likelihood of any in-hospital therapeutic procedure (resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, intra-aortic balloon pumping, temporary/permanent pacemaker, implantable cardiac defibrillator, cardiac resynchronisation therapy) were STEMI versus NSTE-ACS, Killip Class 2/3/4 vs 1/unknown, and LVEF<30% or severely reduced versus other (all p<0.0001) (see online supplementary tables S6 and S8). There was a greatly decreased likelihood of therapeutic procedure in Eastern Europe compared with Northern Europe (p<0.0001). A full list of the variables analysed is shown in the online supplementary table S6.

Any fibrinolytic use

Not surprisingly, the strongest predictor of fibrinolytic use was diagnosis of STEMI (p<0.0001) (see online supplementary table S7). The two other variables with a strong association (p≤0.001) with increased likelihood of any fibrinolytic use were region (more likely in Latin America and Southern Europe compared with Northern Europe) and centre type (university general hospital vs regional/community/rural hospital). Fibrinolytic use was significantly less likely (p<0.0001) in centres with catheterisation laboratory facilities compared with those without.

Discussion

The results of the present analysis indicate that use of antithrombotic medication and PCI is lower in patients with NSTE-ACS than with STEMI, and that, unexpectedly, overall HCRU is slightly lower in patients with than without a history of CVD. Multivariable analyses confirmed that use of technologies and healthcare facilities is disease driven as well as influenced by the supply site characteristics. As a result, there remain large regional differences in treatment patterns.

In the ACCESS survey of ACS management in developing countries, the general pattern of in-hospital management in patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS was similar to that reported here; that is, overall antiplatelet and anticoagulant use was similar by diagnosis but fewer patients with NSTE-ACS than with STEMI received fibrinolytics, fewer had PCI and more underwent CABG.11 Evidence from a meta-analysis of randomised trials suggests that patients with NSTE-ACS do benefit from early coronary intervention in terms of reduced risk of recurrent ischaemia and shorter hospital stay,20 and treatment guidelines recommend early intervention in these patients.3 6 Nevertheless, adherence to such guidance may be suboptimal.10 21

One rather unexpected observation is that fewer than 50% of patients in EPICOR had a prehospital ECG performed. While it is possible that not all external ECGs were captured in the data, it is also feasible that patients who had had a prior ACS recognised their symptoms and were driven to hospital immediately by a family member or friend, rather than waiting for an ambulance.

Overall mean LOS in this analysis was broadly similar in patients with STEMI and NSTE-ACS, varying by about 1 day for both mean (7.2–8.3 days) and median (6–7 days) values. Transfer to a second hospital increased the mean LOS by 1–3 days, with the greatest difference in patients with NSTE-ACS with prior CVD (7.4 vs 10.0 days for non-transferred patients vs those transferred from hospital 1 to 2, respectively). Interestingly, transfer from hospital 1 to 2 and then back again did not appear to increase the overall LOS relative to patients who were only transferred from hospital 1 to 2. A possible explanation may be that when clear rules for transferring patients exist between hospitals, more efficient care can be achieved.

The LOS findings in this study are in keeping with those of the PLATO health economic substudy, where mean LOS for index hospitalisation was approximately 8 days.22 In a German study, median LOS in patients with ACS admitted to the emergency department was also 8 days, but was shortened to 5 days in patients treated in a chest pain unit.23 Similarly, a UK retrospective analysis of ACS admissions found that median LOS was reduced from 7 to 5 days after a 24/7 consultant cardiologist-delivered service was established.24 In a US study of patients with NSTEMI admitted to Acute Coronary Treatment Intervention Outcomes Network Registry–Get With The Guidelines hospitals, median LOS was even shorter, at 3 days.25 These studies suggest that guideline adherence and establishment of a dedicated chest pain unit or cardiologist-delivered service may shorten overall LOS in patients with ACS. The wide range of LOS in our own analysis (1–157 days) may reflect the wide variability among the hospitals and countries included in EPICOR, as well as differences in patient characteristics, particularly related comorbidities. However, as median overall LOS across the patient groups was 6–7 days, it is likely that the longer and shorter stays represent a small number of outliers in each case.

Patients with prior CVD in each diagnostic group were slightly less likely to be transferred to another hospital and less likely to receive CV medication or undergo PCI. However, patients with NSTE-ACS with a history of CVD were most likely to receive a permanent pacemaker, which might be related to older age. It was rather unexpected that patients with a history of CVD received less intensive care overall than those without a history of CVD. There are few previous studies looking specifically at the impact of CVD history on management and HCRU in patients with ACS. One study of patients with NSTE-ACS with or without a history of cerebrovascular disease26 and another in patients with ACS with or without a history of atrial fibrillation,27 both found that patients with a history received fewer evidence-based medical and invasive therapies than those without. Interestingly, 1 year outcomes data from EPICOR showed that initial management strategy (ie, no PCI/CABG) is associated with increased mortality risk in patients with NSTE-ACS.28 It has also been reported that patients with a history of CVD and symptoms of a new STEMI do not call for medical attention any earlier than patients without prior CVD, suggesting a need for education of patients with coronary disease.29

Limitations

One study limitation was the exclusion of HCRU in patients who did not survive the index hospitalisation, as only patients discharged alive were included. It should be noted, however, that survivors of ACS represent a highly relevant group since they are the target population for secondary prevention. An additional limitation was the exclusion of patients transferred out to, and discharged from, a non-participating hospital. Furthermore, use of CV medication in this analysis is reported only as number (per cent) of patients receiving each type of drug, not according to specific dose or combination received, which may have provided more insight into treatment modalities and potential costs. For LOS, there is no separation of time spent in intensive care unit, coronary care unit or general ward, but rather an overall figure. There was also no record of transport (ambulance or otherwise) to the initial hospital, and ambulance transfer between hospitals was recorded in terms of duration rather than distance. Further analysis is required to compare cost data between selected countries or groups of countries.

Conclusions

These results indicate that prehospital and in-hospital HCRU is slightly higher in patients with ACS without, than in those with, a history of CVD. Prehospital antiplatelet use, prehospital and in-hospital use of fibrinolytics, and in-hospital PCI, are more frequent in patients with STEMI than with NSTE-ACS, whereas CABG is more frequent in patients with NSTE-ACS. There are also regional differences in HCRU, such as longer LOS and lower likelihood of coronary intervention in Latin America and Southern Europe compared with Northern Europe. Further analyses will investigate possible differences in follow-up costs between these patient groups.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Liz Anfield, Prime Medica Ltd, Knutsford, Cheshire, UK and funded by AstraZeneca. Statistical analysis was performed by Richard Cairns, Worldwide Clinical Trials, UK.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study, analysis of the study data, and opinions, conclusions and interpretation of the data.

Funding: The EPICOR study was funded by AstraZeneca.

Competing interests: LA has received consulting and lecture fees from AstraZeneca. ND has received consulting or speaking fees from AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GSK, MSD-Schering Plough, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Takeda and The Medicines Company. FVdW has received consulting fees and research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck, and consulting fees from Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. SP has received research funding from AstraZeneca. ML and JM are employees of AstraZeneca. HB has received advisory/consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daichii-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Roche and AstraZeneca, and research grants from AstraZeneca.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The final study protocol was approved in writing by the Ethics Committees of participating centres according to each country's local regulations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The EPICOR study database is the property of AstraZeneca. Data Requests can be sent for consideration through the portal that can be found at www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com, which also includes information on the company Clinical Transparency Policy

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Fact sheet No. 317 2013. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/# (accessed 22 Jul 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vedanthan R, Seligman B, Fuster V. Global perspective on acute coronary syndrome: a burden on the young and poor. Circ Res 2014;114:1959–75. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:e362–425. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2012;126:875–910. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bueno H, Sinnaeve P, Annemans L et al. Opportunities for improvement in anti-thrombotic therapy and other strategies for the management of acute coronary syndromes: insights from EPICOR, an international study of current practice patterns. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puymirat E, Battler A, Birkhead J et al. Euro Heart Survey 2009 Snapshot: regional variations in presentation and management of patients with AMI in 47 countries. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2013;2:359–70. 10.1177/2048872613497341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeymer U, James S, Berkenboom G et al. Differences in the use of guideline-recommended therapies among 14 European countries in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing PCI. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013;20:218–28. 10.1177/2047487312437060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somma KA, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC et al. Guideline adherence after ST-segment elevation versus non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:654–61. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The ACCESS Investigators. Management of acute coronary syndromes in developing countries: acute coronary events—a multinational survey of current management strategies. Am Heart J 2011;162:852–859.e22. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakhai A, Ferrieres J, Iniguez A et al. Clinical outcomes, resource use, and costs at 1 year in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing PCI: results from the multinational APTOR registry. J Interv Cardiol 2012;25:19–27. 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2011.00690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polinski JM, Shrank WH, Glynn RJ et al. Beneficiaries with cardiovascular disease and the Part D coverage gap. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:387–95. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T et al. Age-related differences in treatment strategies and clinical outcomes in unselected cohort of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary angioplasty. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2012;34:214–21. 10.1007/s11239-012-0713-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poon S, Goodman SG, Yan RT et al. Bridging the gender gap: Insights from a contemporary analysis of sex-related differences in the treatment and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2012;163:66–73. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boden H, van der Hoeven BL, Karalis I et al. Management of acute coronary syndrome: achievements and goals still to pursue. Novel developments in diagnosis and treatment. J Intern Med 2012;271:521–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puymirat E, Simon T, Steg PG et al. Association of changes in clinical characteristics and management with improvement in survival among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 2012;308:998–1006. 10.1001/2012.jama.11348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bueno H, Danchin N, Tafalla M et al. EPICOR (long-tErm follow-up of antithrombotic management Patterns In acute CORonary syndrome patients) study: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am Heart J 2013;165:8–14. 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinnaeve PR, Zeymer U, Bueno H et al. Contemporary inter-hospital transfer patterns for the management of acute coronary syndrome patients: findings from the EPICOR study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2015;4:254–62. 10.1177/2048872614551544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katritsis DG, Siontis GC, Kastrati A et al. Optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential intervention in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2011;32:32–40. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putera M, Roark R, Lopes RD et al. Translation of acute coronary syndrome therapies: from evidence to routine clinical practice. Am Heart J 2015;169:266–73. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikolic E, Janzon M, Hauch O et al. Cost-effectiveness of treating acute coronary syndrome patients with ticagrelor for 12 months: results from the PLATO study. Eur Heart J 2013;34:220–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller T, Tzikas S, Scheiba O et al. The length of hospital stay in patients with acute coronary syndrome is reduced by establishing a chest pain unit. Herz 2012;37:301–7. 10.1007/s00059-011-3544-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng Kam Chuen MJ, Schofield R, Sankaranarayanan R et al. Development of a cardiologist delivered service leads to improved outcomes following admission with acute coronary syndromes in a large district general hospital. Acute Card Care 2012; 14:1–4. 10.3109/17482941.2012.655290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vavalle JP, Lopes RD, Chen AY et al. Hospital length of stay in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2012;125:1085–94. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.04.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee TC, Goodman SG, Yan RT et al. Disparities in management patterns and outcomes of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome with and without a history of cerebrovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1083–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Khdair D, Alshengeiti L, Elbarouni B et al. Management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome patients in relation to prior history of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:443–9. 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pocock S, Bueno H, Licour M et al. Predictors of one-year mortality at hospital discharge after acute coronary syndromes: a new risk score from the EPICOR (long-tErm follow uP of antithrombotic management patterns In acute CORonary syndrome patients) study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2015;4:509–17. 10.1177/2048872614554198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puymirat E, Teixeira N, Simon T et al. Patient education after acute myocardial infarction: cardiologists should adapt their message—French registry of acute ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction 2010 registry. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2015;16:761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2015-000347supp_tables.pdf (273.6KB, pdf)