Abstract

Objective

To prospectively assess and describe the emotional, sexual, and QOL concerns of women with early-stage cervical cancer undergoing radical surgery.

Methods

Seventy-one women who were consented for radical trachelectomy (RT) or radical hysterectomy (RH) were enrolled preoperatively in this 2-year study; 52 women (33 RT; 19 RH) were actively followed. Patients completed self-report surveys composed of 4 empirical measures in addition to exploratory items. Data analyses for the 2 years of prospective data are presented.

Results

At preoperative assessment, women choosing RH reported greater concern about cancer recurrence (x=7.27 [scale from 0 to 10]) than women choosing RT (x=5.66) (P=0.008). Forty-eight percent undergoing RH compared to 8.6% undergoing RT reported having adequate “time to complete childbearing” (P<0.001). Both groups demonstrated scores suggestive of depression (based on the CES-D scale) and distress (based on the IES scale) preoperatively; over time, however, CES-D and IES scores generally improved. Scores on the Female Sexual Functioning Inventory (FSFI) for the total sample were below the mean cut-off (26.55), suggestive of sexual dysfunction; however, the means increased from 16.79 preoperatively to 23.78 by 12 months and 22.20 at 24 months.

Conclusion

Measurements of mood, distress, sexual function, and QOL did not differ significantly by surgical type, and instead reflect the challenges faced by young cervical cancer patients treated by RT or RH without adjuvant treatment. Points of vulnerability were identified in which patients may benefit from preoperative consultation or immediate postoperative support. Overall, patients improved during the first year, reaching a plateau between Year-1 and Year-2, which may reflect a new level of functioning in survivorship.

Keywords: Radical trachelectomy, Radical hysterectomy, Quality of life, Adjustment

Introduction

The radical trachelectomy (RT), a fertility-preserving surgery, has gained ever-increasing recognition as a safe oncologic alternative to radical hysterectomy (RH), with similar recurrence rates for early-stage cervical cancer patients of childbearing age [1–6]. Approximately 40% of women diagnosed with early-stage cervical cancer who have undergone RH could have been acceptable candidates for this procedure [7]. With promising obstetrical outcomes, RT offers these women hope of future childbearing [1,3,8,9]. Reproductive concerns have been shown to be associated with quality of life (QOL) [10]; and with advancing technology, future reproductive options have become a paramount concern for many women.

The long-term psychological and QOL impacts of RT are still not fully understood [11,12]. No study has assessed and measured the responses of women undergoing RT in these domains. We have conducted a prospective study designed to examine the emotional, sexual, and QOL concerns of women undergoing RT or RH. This study utilized empirical measures and exploratory items to investigate potential group differences prospectively over 2 years.

Methods

This study is an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved prospective study at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Study informed consent was obtained from participants preoperatively following surgical consent.

Procedure

Women 18–45 years old diagnosed with early-stage cervical cancer (stage IAI with lymphovascular space involvement, IA2–IB2) and consented for RT or RH were approached for study participation. After providing written consent, participants completed a preoperative survey addressing sexual functioning, mood, distress, and QOL, and also qualitative items exploring issues of fertility and treatment choice, and medical/demographic information. Follow-up questionnaires were completed at approximately 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-surgery during medical follow-ups or by telephone if appointments did not coincide with assessment points.

Study survey

The survey consisted of the following:

-

1)

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-Cx) is the FACT-G plus cervix subscale. The Fact-G Version 4 is a 27-item scale measuring QOL in patients with cancer using a 5-point scale (0=not at all, 1=a little bit, 2=somewhat, 3=quite a bit, and 4=very much). Subscales assess physical, functional, emotional, and social well-being [13]. The cervix subscale consists of 15 items specific to symptoms related to cervical cancer. Scores range from 0 to 108 for the FACT-G, and 0 to 60 on the cervix subscale [14].

-

2)

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item scale assessing depressive symptoms using a 4-point scale (0=rarely or none of the time, 1=some of the time, 2=occasionally, and 3=most of the time). Scores of 16 or greater are suggestive of depression [15].

-

3)

Impact of Event Scale (IES) is a 15-item scale to measure the frequency of intrusive and avoidant thoughts/behaviors about “your cancer and treatment” using a 4-point scale (0=not at all, 1=rarely, 3=sometimes, and 5=often). Clinical cut-offs were the following: subclinical (0–8 points), mild (9–25 points), moderate (26–43 points), and severe level of distress (44+ points) [16,17].

-

4)

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) is a 19-item multidimensional scale for assessing sexual functioning in women, including desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Higher scores indicate better sexual functioning. A score <26.55 characterizes sexual dysfunction [18].

-

5)

Background/Medical Information Form: participants were asked to provide demographic information, medical history, cancer history, general medical information, and menstrual/fertility information (fertility treatment, conception attempts, pregnancies, and complications). Qualitative items focusing on fertility issues, treatment choice, and adjustment/concerns regarding treatment and recovery were also included.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were generated to summarize the demographics, medical information, and instrument outcomes. Categorical variables were examined by surgical type using Fisher's exact test. Qualitative data were reviewed by multiple readers to identify thematic categories, and frequencies were computed for the themes. At each of the 6 measurement times, we tested for significant differences between the means of the two groups on each empirical measure using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, calculated using SAS software (Version-9) [19]. Comparisons were made for participants, with complete data for each measure at the given assessment point. Results were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) method [20].

Linear mixed models examined FACT-G, FACT-Cx, CES-D, IES, and FSFI score trajectories over time for the groups, controlling for age at diagnosis. Data from participants with valid preoperative measurements and at least one non-missing follow-up measurement were included in the models. Two models were estimated for each scale using restricted maximum likelihood. The first model contained age at diagnosis, surgery type, time from preoperative assessment (continuous variable calculated from assessment dates), and the interaction between surgery type and time. The second model additionally included a quadratic term for time (i.e., time2) with the interaction between time2 and surgery type. The models including quadratic time fit better than models with only linear terms for each of the 5 scales; thus, they are presented in this manuscript. Random effects were specified for intercepts, time, and time2 (for the second model) to account for dependence of observations within patients over time. Random effect covariance matrix was general, positive-definite, and the within-patient covariance matrix structure was independent. A first-order autoregressive within-patient covariance matrix was tested for each outcome but did not improve model fit over the independent covariance matrix specification. Model-estimated scores for each surgery group at each of the 6 assessment times were plotted to visually depict the trajectories over time. All linear mixed model analyses used the nlme package [21] in the R statistical computing environment [22].

Recruitment

From 2/04 to 1/08, 71 women who were consented for RT or RH (43 RT; 28 RH) were enrolled and completed preoperative surveys. Postoperative treatment (chemotherapy, and/or radiation treatment) was a violation of IRB eligibility criteria due to concerns about confounding variables and sample size. Consequently, 15 (21%) of the 71 patients (9 RT; 6 RH) were excluded for this reason. Four additional patients were withdrawn: 2 surgeries were aborted due to extent of disease (RH); 1 patient consented for surgery but later declined surgery (RT); and 1 patient had severe psychiatric issues postoperatively (RH). Preoperative data will reflect the 71 women consented for surgery (43 RT; 28 RH), but the postoperative sample and data analysis will only include the 52 women (33 RT; 19 RH) who completed at least one assessment postoperatively. Of note, 4 patients were also withdrawn over the course of the study—1 patient was lost to follow-up after 3 months postoperatively (RH), 1 patient no longer wished to participate in the study after the 18-month survey, and 2 patients recurred (1 RT patient and 1 RH patient) while on study.

Results

Preoperative assessment for the total sample (n=71)

3.1.1. Demographic characteristics

Participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 45 years (mean=34.5). RT patients (mean=32.6) were younger than RH patients (mean=37.6). Over half of the patients were married/or living with someone (58%, n=41); approximately one-third were single (35%, n=25); and 68% (n=48) had no children at enrollment. Table 1 presents further demographic information.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics (N=71).

| Demographic characteristics at time of enrollment |

Radical trachelectomy (n = 43) |

Radical hysterectomy (n = 28) |

Total sample (n = 71) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | Mean (SE) 32.55 (0.69) | Mean (SE) 37.58 (1.14) | Mean (SE) 34.54 (0.67) | |||

| Marital Status | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Single | 16 | 37% | 9 | 32% | 25 | 35% |

| Married or living with someone | 24 | 56% | 17 | 61% | 41 | 58% |

| Separated or divorced | 3 | 7% | 2 | 7% | 5 | 7% |

| Children | ||||||

| Number of Children: No children | 36 | 84% | 12 | 43% | 48 | 68% |

| 1 child | 6 | 14% | 5 | 18% | 11 | 16% |

| 2 children | 1 | 2% | 6 | 21% | 7 | 10% |

| 3 or more children | 0 | 0% | 5 | 18% | 5 | 7% |

| Education | ||||||

| 11th grade or less | – | – | 2 | 7% | 2 | 3% |

| High school graduate or GED | 6 | 14% | 2 | 7% | 8 | 11% |

| Some college | 8 | 19% | 6 | 21% | 14 | 20% |

| College graduate | 10 | 23% | 9 | 32% | 19 | 27% |

| Graduate school training | 19 | 4435 | 9 | 32% | 28 | 39% |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 40 | 93% | 24 | 86% | 64 | 90% |

| Black | – | – | 2 | 7% | 2 | 3% |

| Asian | 3 | 7% | 2 | 7% | 5 | 7% |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 8 | 19% | 3 | 11% | 11 | 15% |

| Non-Hispanic | 35 | 81% | 23 | 32% | 58 | 82% |

| Preferred not to answer | – | – | 2 | 7% | 2 | 3% |

Medical characteristics and treatment choice

Preoperatively, 43 women (61%) consented for RT and 28 (39%) for RH. Of the women consented for RT, the majority indicated fertility and not having enough time to complete childbearing as factors in the treatment decision-making process (Table 2). Women undergoing RH demonstrated mixed responses, with approximately half indicating fertility or childbearing as factors in treatment choice. Almost the entire RT sample (n=42) reported preoperatively a desire for ovarian preservation for future fertility options or menopause prevention, whereas 6 of 28 women planned for RH expressed desire for ovarian removal (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [BSO]). A few women consented for RH provided additional insight in their qualitative items, revealing concerns of cancer spread and/or menopause prevention.

Table 2.

Medical characteristics and treatment choice.

| Preoperative sample (n= 71) | Radical trachelectomy (n = 43) |

Radical hysterectomy (n = 28) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Type of surgery | 43 | 61% | 28 | 39% |

| Desire to preserve ovaries | Yes: 36 | 84% | Yes: 16 | 57% |

| No: 0 | - | No: 6 | 21.5% | |

| Missing: 7 | 16% | Missing: 6 | 21.5% | |

| Time to complete childbearing | Yes: 3 | 7% | Yes: 12 | 43% |

| No: 32 | 74% | No: 13 | 46% | |

| Missing: 8 | 19% | Missing: 3 | 11% | |

| Fertility factor in decision-making | Yes: 42 | 98% | Yes: 13 | 46% |

| No: - | - | No: 15 | 54% | |

| Missing: 1 | 2% | Missing: - | - | |

| Required postoperative adjuvant treatment | 9 | 21% | 6 | 21% |

| Postoperative sample: (n = 52) | n | % | ||

| Type of radical trachelectomy (n = 33): | ||||

| Vaginal | 25 | 76% | ||

| Abdominal | 8 | 24% | ||

| Radical hysterectomy (n = 19) | Yes: 14 | 74% | ||

| BSO | No: 5 | 26% | ||

BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Seven percent of RT patients reported having had enough time to complete childbearing compared to 43% of RH patients (P<0.001; Fisher's exact test). Women in the RT group (98% response-rate) reported qualitative themes of fertility (55%, n=23), doctor discussion/recommendation (36%, n=15), and research (17%, n=7) as important factors guiding treatment choice. Among the women consented for RH, 24 (86%) of 28 provided qualitative information. Reasons for choosing this surgical procedure included themes of doctor discussion/recommendation (46%, n=11), similar to those noted in the RT group; however, additional themes of “concern about survival” (25%, n=6) and feeling this was the “best option or only choice” (25%, n=6) were also noted.

Prospective data for 2-year assessment (n=52)

All 52 women remaining on study postoperatively completed at least 2 assessments. All RT patients (100%, n=33) and 84% (16/19) of RH patients completed at least 3 assessments. Although the two groups had differential attrition rates, we found no evidence of preoperative differences on CES-D, IES, FACT-Cx, and FSFI scores between patients with only 2 versus 3 assessments.

Empirical measures: mood, distress, QOL and sexual function

No statistical group differences were noted after correcting for multiple comparisons; however, both RT and RH groups’ scores generally improved over the follow-up period (Tables 3 and 4). Mood: Preoperatively, CES-D mean scores for both groups were suggestive of depression (RT, 17.48; RH, 20.3). Postoperatively, the means remained in the subclinical range (<16); however, a slight increase to 16.77 was noted at 6 months for RT patients. Distress: Both groups experienced persistent clinical levels of distress (IES≥9 points) about their cancer and treatment. The intensity of distress lessened over time for all, falling within the range of mild distress (9–25 points, mean = 18.13) by 12 months and further (mean = 14.29) by 24 months. No statistically significant group differences were found for IES total or subscales (avoidance and intrusion). QOL: Preoperative scores were lower than postoperative scores, suggesting improvement of QOL over time for both groups. The RT group had a higher preoperative mean (23.17) on the FACT-Cx subscale social/family well-being, indicating more support (P=0.017); however, after correction for multiple comparisons, this difference was not significant. Sexual function: Our total sample scored in the range of sexual dysfunction (≤26.55) throughout the 2 years (Table 5). The RH group demonstrated higher FSFI means (12 months, mean=4.97) on the orgasm subscale, suggesting better functioning for this domain than the RT group at 12 months (mean=3.71, P=0.044); however, after correction for multiple comparisons, this difference was not significant.

Table 3.

Means of instruments at baseline and follow-up, overall, and by surgery type.

| Radical trachelectomy |

Radical hysterectomy |

Overall |

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n | Mean | (SE) | Total n | Mean | (SE) | Total n | Mean | (SE) | P value | ||

| Concern cancer will come back | |||||||||||

| (O: not at all to 10 very concerned) | Initial assessment | 43 | 5.66* | (0.39) | 28 | 7.27* | (0.56) | 71 | 6.3 | (0.34) | 0.008* |

| 3-month follow-up | 28 | 5.91 | (0.45) | 14 | 4.96 | (0.5) | 42 | 5.6 | (0.34) | 0.147 | |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 5.6 | (0.31) | 14 | 5.36 | (0.78) | 45 | 5.52 | (0.32) | 0.682 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 5.16 | (0.35) | 13 | 5.08 | (0.75) | 42 | 5.13 | (0.33) | 0.923 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 4.61 | (0.41) | 11 | 5.27 | (0.69) | 38 | 4.80 | (0.35) | 0.376 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 4.21 | (0.42) | 14 | 4.86 | (0.81) | 40 | 4.44 | (0.39) | 0.529 | |

| CES-D total score | |||||||||||

| Range = 0 to 60 | Initial assessment | 42 | 17.48 | (1.83) | 27 | 20.3 | (2.61) | 69 | 18.58 | (1.51) | 0.382 |

| Clinical cut-off: 16+ depression | 3-month follow-up | 28 | 13.4 | (1.69) | 15 | 14.13 | (3.19) | 43 | 13.66 | (1.54) | 0.990 |

| 6-month follow-up | 30 | 16.77 | (2.55) | 14 | 8.91 | (2.28) | 44 | 14.27 | (1.95) | 0.082 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 10.59 | (2.17) | 13 | 10.08 | (2.75) | 42 | 10.43 | (1.7) | 0.881 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 11.96 | (0.41) | 11 | 8.36 | (1.50) | 38 | 10.92 | (1.80) | 0.922 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 10.04 | (2.21) | 14 | 11.14 | (2.91) | 40 | 10.43 | 1.74 | 0.579 | |

| FSFI total score | |||||||||||

| Range = 0 to 95 | Initial assessment | 43 | 17.43 | (1.79) | 26 | 15.72 | (2.3) | 69 | 16.79 | (1.4) | 0.696 |

| Clinical cut-off: <26.55 sexual dysfunction | 3-month follow-up | 28 | 17.29 | (1.91) | 15 | 20.58 | (2.45) | 43 | 18.43 | (1.51) | 0.268 |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 20.8 | (1.82) | 14 | 23.66 | (2.78) | 45 | 21.69 | (1.52) | 0.309 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 23.04 | (1.79) | 13 | 25.44 | (2.55) | 42 | 23.78 | (1.46) | 0.496 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 25 | 23.14 | (2.16) | 10 | 25.01 | (2.70) | 35 | 23.68 | (1.71) | 0.971 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 21.97 | (2.27) | 14 | 22.63 | (2.91) | 40 | 22.20 | (1.77) | 0.921 | |

| IES total score | |||||||||||

| Clinical cut-offs: 0-8 subclinical | Initial assessment | 42 | 35.39 | (2.4) | 26 | 33.63 | (3.54) | 68 | 34.72 | (1.99) | 0.760 |

| 9-25 Mild | 3-month follow-up | 27 | 25.89 | (3.24) | 15 | 23.4 | (4.82) | 42 | 25 | (2.67) | 0.780 |

| 26-43 Moderate | 6-month follow-up | 31 | 27.42 | (3.29) | 14 | 26.14 | (5.74) | 45 | 27.03 | (2.85) | 0.750 |

| 44+ Severe | 12-month follow-up | 29 | 17.07 | (2.79) | 13 | 20.48 | (3.11) | 42 | 18.13 | (2.15) | 0.240 |

| Range = 0 to 75 | 18-month follow-up | 27 | 18.93 | (3.25) | 11 | 14.55 | (2.21) | 38 | 17.66 | (2.40) | 0.772 |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 13.65 | (2.75) | 14 | 15.46 | (3.05) | 40 | 14.29 | (2.06) | 0.379 | |

| FACT Phys well-being | |||||||||||

| Range= 0 to 28 | Initial assessment | 42 | 24.68 | (0.59) | 27 | 22.4 | (1.14) | 69 | 23.79 | (0.58) | 0.068 |

| 3-month follow-up | 28 | 24.35 | (0.68) | 15 | 21.86 | (1.68) | 43 | 23.48 | (0.75) | 0.170 | |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 23.01 | (0.94) | 13 | 24.31 | (1.43) | 44 | 23.39 | (0.78) | 0.218 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 25.76 | (0.6) | 13 | 25.15 | (0.93) | 42 | 25.57 | (0.5) | 0.369 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 24.57 | (0.84) | 11 | 26.36 | (0.45) | 38 | 25.09 | (0.62) | 0.442 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 26.12 | (0.38) | 14 | 26.13 | (0.58) | 40 | 26.12 | (0.31) | 0.965 | |

| FACT Soc/family well-being | |||||||||||

| Range= 0 to 28 | Initial assessment | 42 | 23.17* | (0.77) | 28 | 20.33* | (0.99) | 70 | 22.04 | (0.63) | 0.017* |

| 3-month follow-up | 28 | 20.92 | (1.26) | 15 | 22.86 | (0.99) | 43 | 21.59 | (0.89) | 0.583 | |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 20.58 | (1.18) | 13 | 23.15 | (1.04) | 44 | 21.34 | (0.9) | 0.394 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 22.11 | (1.08) | 13 | 22.69 | (1.04) | 42 | 22.29 | (0.81) | 0.978 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 21.27 | (1.25) | 11 | 23.55 | (1.06) | 38 | 21.93 | (0.95) | 0.560 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 21.77 | (1.08) | 14 | 22.17 | (1.34) | 40 | 21.91 | (0.84) | 0.955 | |

| FACT emotional well-being | |||||||||||

| Range= 0 to 24 | Initial assessment | 43 | 13.79 | (0.64) | 28 | 12.31 | (1.11) | 71 | 13.2 | (0.59) | 0.197 |

| 3-month follow-up | 28 | 17.61 | (0.56) | 15 | 18.95 | (0.86) | 43 | 18.07 | (0.48) | 0.143 | |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 17.19 | (0.71) | 14 | 18.64 | (1.47) | 45 | 17.64 | (0.67) | 0.157 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 18.9 | (0.76) | 13 | 16.98 | (1.49) | 42 | 18.3 | (0.7) | 0.229 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 18.96 | (0.78) | 11 | 18.27 | (0.99) | 38 | 18.76 | (0.62) | 0.383 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 19.42 | (0.55) | 14 | 19.57 | (1.01) | 40 | 19.48 | (0.49) | 0.775 | |

| FACT functional well-being | |||||||||||

| Range= 0 to 28 | Initial assessment | 43 | 19.48 | (0.86) | 28 | 17.07 | (1.3) | 71 | 18.53 | (0.74) | 0.166 |

| 3-month follow-up | 28 | 21.99 | (0.9) | 15 | 18.42 | (1.9) | 43 | 20.74 | (0.91) | 0.105 | |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 21.32 | (1.05) | 14 | 22.5 | (1.33) | 45 | 21.69 | (0.83) | 0.579 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 23.52 | (0.94) | 13 | 21.85 | (1.4) | 42 | 23 | (0.78) | 0.170 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 22.81 | (1.11) | 11 | 23.91 | (1.11) | 38 | 23.13 | (0.85) | 0.820 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 23.92 | (0.96) | 14 | 21.86 | (1.50) | 40 | 23.20 | (0.82) | 0.257 | |

| FACT-G total score | |||||||||||

| Range= 0 to 108 | Initial assessment | 42 | 80.92 | (2.02) | 27 | 72.32 | (3.63) | 69 | 77.55 | (1.93) | 0.063 |

| 3-month follow-up | 28 | 84.85 | (1.96) | 15 | 82.09 | (4.45) | 43 | 83.89 | (1.99) | 0.889 | |

| 6-month follow-up | 31 | 82.1 | (3.16) | 13 | 89.15 | (4.08) | 44 | 84.19 | (2.55) | 0.316 | |

| 12-month follow-up | 29 | 90.28 | (2.7) | 13 | 86.68 | (4.01) | 42 | 89.17 | (2.23) | 0.294 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 27 | 87.62 | (3.29) | 11 | 92.09 | (2.57) | 38 | 88.91 | (2.45) | 0.936 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 26 | 91.23 | (2.46) | 14 | 89.73 | (3.70) | 40 | 90.70 | (2.03) | 0.809 | |

Indicates that the means for the two surgery groups were significantly different, P<0.05, before correcting for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method. No test remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Table 4.

Percentages of categorical outcomes at baseline and follow-up, overall and by surgery.

| Trachelectomy |

Radical hysterectomy |

Overall |

Fisher's exact test P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n | % | Total n | % | Total n | % | |||

| Above CES-D clinical cut-off | ||||||||

| (16+ is the clinical cut-off) | At initial assessment | 42 | 47.62 | 27 | 51.85 | 69 | 49.28 | 0.808 |

| At 3-month follow-up | 28 | 28.57 | 15 | 40.00 | 43 | 32.56 | 0.507 | |

| At 6-month follow-up | 30 | 46.67 | 14 | 21.43 | 44 | 38.64 | 0.184 | |

| At 12-month follow-up | 29 | 20.69 | 13 | 15.38 | 42 | 19.05 | 0.990 | |

| At 18-month follow-up | 27 | 29.63 | 11 | 9.09 | 38 | 23.68 | 0.237 | |

| At 24-month follow-up | 26 | 30.77 | 14 | 21.43 | 40 | 27.50 | 0.7152 | |

| FSFI dysfunctional | ||||||||

| (Less than 26) | At initial assessment | 43 | 69.77 | 26 | 73.08 | 69 | 71.01 | 0.990 |

| At 3-month follow-up | 28 | 75.00 | 15 | 60.00 | 43 | 69.77 | 0.324 | |

| At 6-month follow-up | 31 | 61.29 | 14 | 42.86 | 45 | 55.56 | 0.336 | |

| At 12-month follow-up | 29 | 55.17 | 13 | 46.15 | 42 | 52.38 | 0.741 | |

| At 18-month follow-up | 25 | 52.00 | 10 | 50.00 | 35 | 51.43 | 1.000 | |

| At 24-month follow-up | 26 | 50.00 | 14 | 64.29 | 40 | 55.00 | 0.510 | |

| IES = 26 or greater | ||||||||

| (Moderate distress) | At initial assessment | 42 | 73.81 | 26 | 80.77 | 68 | 76.47 | 0.570 |

| At 3-month follow-up | 27 | 55.56 | 15 | 40.00 | 42 | 50.00 | 0.520 | |

| At 6-month follow-up | 31 | 48.39 | 14 | 50.00 | 45 | 48.89 | 0.990 | |

| At 12-month follow-up | 29 | 24.14 | 13 | 38.46 | 42 | 28.57 | 0.460 | |

| At 18-month follow-up | 27 | 40.74 | 11 | 9.09 | 38 | 31.58 | .121 | |

| At 24-month follow-up | 26 | 19.23 | 14 | 14.29 | 40 | 17.50 | 1.00 | |

Table 5.

Female sexual functioning index (FSFI) scores of sample in comparison to published FSFI scores.

| Radical trachelectomy Initial | Radical trachelectomy 3 months | Radical trachelectomy 6 months | Radical trachelectomy 12 months | Radical trachelectomy 18 month | Radical trachelectomy 24 month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI total | Mean: 17.43 (n = 43; SE: 1.79) | Mean: 17.29 (n = 28; SE: 1.91) | Mean: 20.8 (n = 31; SE: 1.82) | Mean: 23.04 (n = 29; SE: 1.79) | Mean: 23.14 (n = 25; SE: 2.16) | Mean: 21.97 (n = 26; SE: 2.27) |

| Desire | Mean: 3.01 (n = 42; SE: 0.19) | Mean: 3.21 (n = 28; SE; 0.24) | Mean: 3.27 (n = 31; SE: 0.26) | Mean: 3.62 (n = 29; 0.24) | Mean: 3.78 (n = 26; SE: 0.29) | Mean: 3.78 (n = 26; SE: 0.23) |

| Arousal | Mean: 3.1 (n = 43; SE: 0.34) | Mean: 2.91 (n = 28; SE: 0.33) | Mean: 3.44 (n = 31; 0.33) | Mean: 3.88 (n = 29; SE: 0.33) | Mean: 3.66 (n = 26; SE: 0.42) | Mean: 3.45 (n = 26; SE: 0.47) |

| Lubrication | Mean: 3.13 (n = 43; SE: 0.39) | Mean: 3.32 (n = 26; SE: 0.45) | Mean: 3.9 (n = 30; SE: 0.39) | Mean: 4.12 (n = 29; SE: 0.37) | Mean: 4.45 (n = 25; SE: 0.43) | Mean: 4.03 (n = 26; SE: 0.48) |

| Orgasm | Mean: 2.84 (n = 43; SE: 0.39) | Mean: 2.8 (n = 26; SE: 0.42) | Mean: 3.71 (n = 30; SE: 0.39) | Mean: 3.71 (n = 29; SE: 0.38)a | Mean: 3.73 (n = 25; SE: 0.45) | Mean: 3.46 (n = 26; SE: 0.47) |

| Satisfaction | Mean: 3.18 (n = 43; SE: 0.29) | Mean: 3.02 (n = 27; SE: 0.3) | Mean: 3.43 (n = 31; SE: 0.3) | Mean: 3.99 (n = 29; SE: 0.29) | Mean: 3.66 (n = 25; SE: 0.41) | Mean: 3.71 (n = 26; SE: 0.39) |

| Pain | Mean: 2.23 (n = 43; SE: 0.41) | Mean: 2.75 (n = 26; SE: 0.49) | Mean: 3.3 (n = 31; SE: 0.43) | Mean: 3.72 (n = 29; SE: 0.45) | Mean: 3.63 (n = 25; SE: 0.50) | Mean: 3.54 (n = 26; SE: 0.49) |

| Radical hysterectomy Initial | Radical hysterectomy 3 months | Radical hysterectomy 6 months | Radical hysterectomy 12 months | Radical hysterectomy 18 months | Radical hysterectomy 24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI total | Mean: 15.72 (n = 26; SE: 2.3) | Mean: 20.58 (n = 15; SE: 2.45) | Mean: 23.66 (n = 14; SE: 2.78) | Mean: 25.44 (n = 13; SE: 2.55) | Mean: 25.01 (n = 10; SE: 2.70) | Mean: 22.63 (n = 14; SE: 2.91) |

| Desire | Mean: 3.14 (n = 26; SE: 0.24) | Mean: 3.48 (n = 15; SE: 0.35) | Mean: 3.6 (n = 14; SE: 0.33) | Mean: 3.42 (n = 13; SE: 0.38) | Mean: 3.78 (n = 10; SE: 0.39) | Mean: 3.64 (n = 14; SE: 0.34) |

| Arousal | Mean: 2.43 (n = 26; SE: 0.42) | Mean: 3.52 (n = 15; SE: 0.45) | Mean: 3.92 (n = 14; SE: 0.54) | Mean: 4.2 (n = 13; SE: 0.53) | Mean: 4.38 (n-10; SE: 0.50) | Mean: 3.66 (n = 14; SE: 0.56) |

| Lubrication | Mean: 2.7 (n = 26; SE: 0.52) | Mean: 3.34 (n = 15; SE: 0.6) | Mean: 4.08 (n = 13; SE: 0.54) | Mean: 4.88 (n = 12; SE: 0.36) | Mean: 4.17 (n = 10; SE: 0.63) | Mean: 3.84 (n = 14; SE: 0.61) |

| Orgasm | Mean: 2.5 (n = 25; SE: 0.5) | Mean: 3.39 (n = 15; SE: 0.51) | Mean: 4.89 (n = 13; SE: 0.5) | Mean: 4.97 (n = 12; SE: 0.49)a | Mean: 4.32 (n = 10; SE: 0.59) | Mean: 3.89 (n = 14; SE: 0.68) |

| Satisfaction | Mean: 2.58 (n = 26; SE: 0.4) | Mean: 3.55 (n = 15; SE: 0.47) | Mean: 4.25 (n = 13; SE: 0.45) | Mean: 4.53 (n = 12; SE: 0.33) | Mean: 4.12 (n = 10; SE: 0.58) | Mean: 4.03 (n = 14; SE: 0.48) |

| Pain | Mean: 2.91 (n = 22; SE: 0.59) | Mean: 3.31 (n = 15; SE: 0.6) | Mean: 4.15 (n = 13; SE: 0.5) | Mean: 4.93 (n = 12; SE: 0.5) | Mean: 4.24 (n = 10; SE: 0.59) | Mean: 3.57 (n = 14; SE: 0.70) |

| Normativeb | Breast sampleb | GYN infertility samplec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI total | 30.75 | 17.85 | 19.76 |

| Desire | 4.28 | 3.14 | 3.23 |

| Arousal | 5.08 | 2.67 | 3.29 |

| Lubrication | 5.45 | 3.01 | 3.11 |

| Orgasm | 5.05 | 2.84 | 3.54 |

| Satisfaction | 5.04 | 3.26 | 3.59 |

| Pain | 5.51 | 3.32 | 3.25 |

The means for the two surgery groups were significantly different, P<0.05, before correcting for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method. No test remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Schover et al. (2006).

Carter et al. (2010).

Exploratory items

Fear of cancer recurrence

Participants rated their degree of worry about cancer recurrence on a scale from 0 to 10 (0=not at all to 10=very concerned). Preoperatively, RH patients (x=7.27) were more concerned about cancer recurrence than women choosing RT (x=5.66, P=0.008), but this was not statistically significant after controlling for multiple comparisons. No statistical group differences were noted over time. Regardless of surgery type, these women with early-stage cervical cancer had concerns of recurrence. Mean scores ranged between 4 and 6 points (out of 10) throughout the 2 years (Table 3).

Reproductive concerns

RT patients were asked “Do you have concerns about trying to conceive a baby in the future?” and preoperatively, 39 (91%) indicated concerns. At 6 months, 29 (88%) of 33 RT participants responded affirmatively as well. By Year-1, 25 (76%) of 33 indicated persistent concerns, which declined to 73% (n=24) by Year-2. On a scale from 0 to 100%, participants were also asked to rate “How successful do you think you will be at conceiving in the future?” Preoperatively, mean ratings were 61.8%, ranging from 25 to 100% (n=41). Mean ratings increased over time (6 months, 53.7% (n=31); Year-1, 55.4% (n=29); and Year-2, 59.8% (n=26)). Based on self-report data, 15% (n=5) of participants had spoken to an infertility specialist within the first year, which slightly increased to 18% (n=6) by Year-2. RT participants were also asked for information regarding conception. At Year-1, 6% (n=2) were trying to conceive, 9% (n=3) had achieved conception since surgery, and 6% (n=2) were pregnant. At final assessment in Year-2, 21% (n=7) were attempting conception, 15% (n=5) had successfully conceived, and 9% (n=3) achieved pregnancy. At study completion, 1 participant was still pregnant and 8 babies had been born.

Longitudinal trajectories of emotional function, QOL, and sexual function

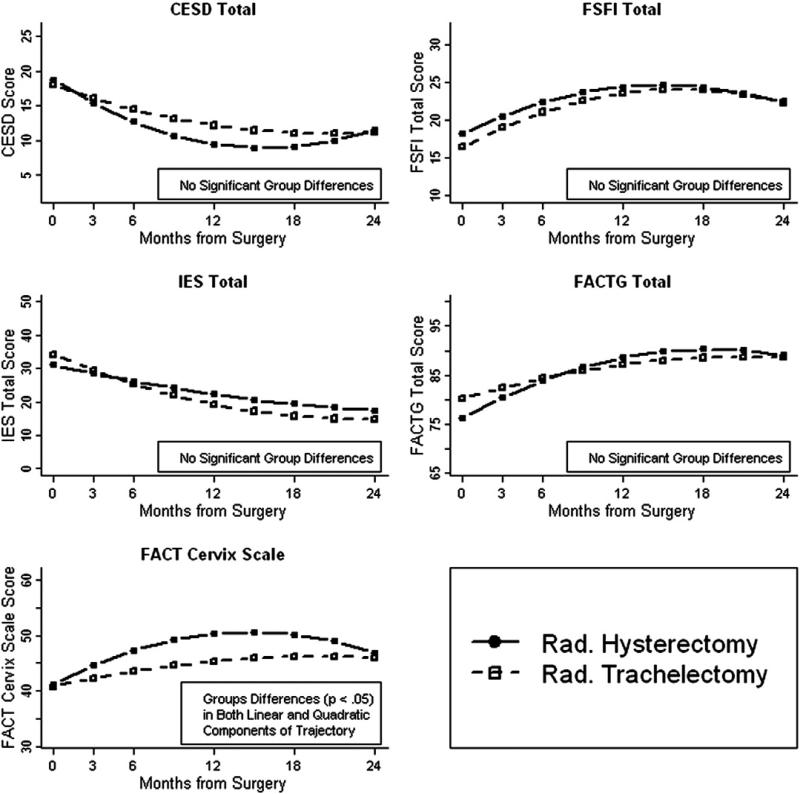

The model-estimated mean scores by assessment time for each surgery group adjusted for age at diagnosis (Fig. 1). All models suggested similar baseline values on the 5 scales for the two groups. In addition, the trajectories over time for the groups were similar for all outcomes except for the FACT-Cx. Compared to the gradual improvement over time in RT patients, RH patients had a significantly more marked initial improvement over the first year followed by a significantly more pronounced downward arc in their FACT-Cx trajectory. Follow-up analysis indicated that the reproductive concern item was elevated for the RT group. This should be interpreted cautiously, however, since these trajectory differences result in a maximum mean difference of only 5 points (at 12 months) between the groups. Additionally, the RH group was roughly only half the size of the RT group and had a slightly higher attrition rate.

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal trajectories of scale scores by surgery type. Coordinates represent the fitted means at each time point from linear mixed models adjusted for age at diagnosis. Higher scores for CES-D and IES reflect worse symptoms; higher scores for the FSFI, FACT-G, and FACT-Cx scales reflect better functioning. Significant group differences were found only for the FACT-Cx scale, in which the radical trachelectomy patients had a significantly more gradual linear improvement as well as a significantly less-prounounced arc in their trajectory compared to the radical hysterectomy patients. Follow-up analysis revealed that these group differences were primarily due to greater radical trachelectomy endorsement of an item assessing concern about the ability to have children.

Collectively, these results suggest that both groups had improvement in their mood, distress, sexual functioning, QOL, and cervical cancer-specific concerns during postoperative Year-1, after which the rate of improvement decreased and leveled off between Year-1 and Year-2. Although some of the figures seem to suggest that functioning may decrease after the first year of improvement, we propose that this may be due to normal, expected day-to-day fluctuations rather than to reliable, systematic oncological causes.

Discussion

During the conceptualization of this study, we hypothesized that women undergoing fertility-preserving treatment would demonstrate more adaptive or favorable responses than those undergoing RH. The scores on measurements of mood, distress, sexual function, and QOL did not differ significantly between groups. However, both groups demonstrated emotional and physical ramifications to their cancer diagnosis, treatment, and immediate postoperative recovery. Much of the existing literature has described the experience of cervical cancer patients requiring radiation therapy and its associated treatment sequelae or advanced disease. This prospective study explored the experiences of young early-stage cervical cancer patients treated with surgery alone.

As noted in a previous publication, women choosing to undergo RT were guided by conversations with their doctors [11]. This was also an important factor for women selecting RH. All participants underwent consultations with a surgeon and consented before completing the preoperative survey. Qualitative data identified distinct thematic differences between the surgical groups. Not surprisingly, treatment choice was heavily influenced by the desire to preserve fertility within the RT sample, with more RH patients reporting adequate time to complete childbearing (P<0.001). While RT patients expressed a greater desire to preserve fertility in their qualitative responses, themes of cancer worry (i.e., cancer spread/recurrence) were cited by some of the women choosing RH. This theme was also reflected by the degree of worry about cancer recurrence. Preoperatively, women choosing RH also demonstrated a higher degree of cancer worry on the 0–10 scale (mean=7.27) compared to women selecting RT (mean=5.66, P=0.008). While all patients had early-stage disease with similar risks for recurrence, it is possible that those who were more concerned about cancer recurrence may have opted for the standard of care – RH – but further clarification is needed.

Preoperative results indicated high levels of distress (IES) and symptoms of depression (CES-D) for all participants newly diagnosed and preparing for surgical treatment. Although these findings are not surprising, they highlight the importance of baseline measurements to adequately understand the impact of a cancer diagnosis as well as revealing an important time point for intervention. At our institution, preoperative consultations with mental health professionals are routinely offered. Many cancer patients are challenged to ponder their own mortality while considering possible treatment risks (loss of fertility/premature menopause) and uncertainty dependent upon surgical staging and final pathology review.

It appears that both cohorts postoperatively demonstrated an adaptive process over 2 years. The fluctuations in scores noted after 12–18 months in Fig. 1 and Table 3 seem to fall close to or within the boundary of “normal” functioning levels. We hypothesize that this trend may be indicative of the subjects reaching what their level of functioning will be in cancer survivorship.

The QOL scores of our sample as measured by the FACT are consistent with the published means [14,23]. Our early-stage cervical cancer patients’ QOL mean scores ranged from 77.55 at baseline to 89.17 at Year-1 and 90.70 at Year-2. These scores are similar to other cervical cancer survivors, yet still reflect a QOL disruption. Preoperatively, the RT group scored higher on the social/family well-being subscale of the FACT; however, it is unclear if this factor had any impact on the treatment decision process, but would be important to explore in future studies.

The findings of the FSFI, measuring the sexual functioning for the sample, were unexpected. Based on the literature, we hypothesized that sexual functioning would not be significantly impaired since ovarian function would remain intact and participants remaining on study did not receive any postoperative therapy (i.e., radiation and/or chemotherapy). However, we did propose possible differences between the groups based on surgical type. Even though both procedures can be viewed as invasive, RT is more conservative, allowing for uterine preservation; thus, it was proposed that this cohort would fare better. However, FSFI mean scores, regardless of proposed surgical type, fell below 26.55—the clinical cut-off [18] indicative of sexual dysfunction. Preoperatively, mean scores on the FSFI were comparable to other cohorts of young cancer survivors [24,25]. Although it is reasonable that women coping with a new cancer diagnosis and proposed surgical intervention would exhibit disruption in sexual functioning, the scores remained unexpectedly below the clinical cut-off over time. RT patients, who had no postoperative adjuvant treatment and intact ovaries, reported sexual function scores comparable not only to RH patients but also to other young cancer survivors with cancer-related infertility and/or premature menopause (Table 5). This finding may be associated with the neocervical stenosis experienced by RT patients. Neocervical stenosis may contribute to discomfort, which in turn could have a negative impact on sexual response [1,12] and may offer some possible explanation for the scores on the FSFI orgasm subscale. Despite scoring in the range of sexual dysfunction, improvement in sexual functioning did occur over time.

Our sample size was small, and although we may not have had adequate power to detect very small differences between the groups on the outcome measures, the study was adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful differences. Reasons for our small sample size were partially due to study criteria and the common challenges of attrition with prospective study designs. Attrition was noted to be more prevalent in the RH group, which may reflect a greater investment by RT patients on the research topic. We acknowledge that our findings do not reflect all women undergoing RH or RT, since our sample excluded women needing postoperative treatment. It would have been ideal to capture all the experiences of early-stage cervical cancer patients, but that exceeds the capacity of a single institution with the large sample size that would be required for such an investigation. A cooperative group study may be the mechanism for future investigation. Our sample was demographically homogenous, but this may be reflective of the women researching fertility-preserving options or those referred to a major cancer center. However, the results of this study provide important information and guidance for future investigation with diverse samples of cervical cancer patients.

Fertility-preserving surgery is an important option for young women seeking treatment for early-stage cervical cancer. RT has almost 2 decades of data to support its feasibility as a treatment approach in select patients. Despite the positive outcome of potential childbearing in cancer survivorship for these women, this study documents preoperative struggles faced by all young cervical cancer patients in the midst of considering treatment options, and their vulnerability during the immediate postoperative period. Our early-stage cervical cancer patients without any evidence of disease or postoperative treatment showed gradual improvement over time, with a plateau between Year-1 and Year-2, which may reflect a new level of functioning within cancer survivorship. Overall, the results of this study provide useful information to enhance preoperative discussions, which can assist patients in having clear expectations for the recovery process and function in survivorship.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: T.J. Martell Foundation and MSKCC Gynecology Philanthropic Funds.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement

Jeanne Carter, PhD: none; Yukio Sonoda, MD: Speaker for Genzyme; Dennis S. Chi, MD: Speaker for Genzyme; Richard R. Barakat, MD: none; Raymond E. Baser, MS: none; Leigh Raviv, BA: none; Alexia Iasonos, PhD: none; Carol L. Brown, MD: none; and Nadeem R. Abu-Rustum, MD: none.

References

- 1.Plante M. Vaginal radical trachelectomy: an update. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:S105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milliken DA, Shepherd JH. Fertility preserving surgery for carcinoma of the cervix. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:575–80. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32830b0dc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd JH, Spencer C, Herod J, Ind TE. Radical vaginal trachelectomy as fertility-sparing procedure in women with early stage cervical cancer-cumulative pregnancy rate in a series of 123 women. BJOG. 2006;4:353–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz JP, Sonoda Y, Leitao MM, Zivanovic O, Brown CL, Chi DS, et al. Oncologic outcome of fertility-sparing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for stage IB1 cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:255–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Einstein MH, Park KJ, Sonoda Y, Carter J, Chi DS, Barakat RR, et al. Radical vaginal versus abdominal trachelectomy for stage IB1 cervical cancer: a comparison of surgical and pathologic outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pareja RF, Ramirez PT, Borrero MF, Angel CG. Abdominal radical trachelectomy for invasive cervical cancer: a case series and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Gemignani ML, Chi DS, Brown CL, Poynor EA, et al. A fertility-sparing alternative to radical hysterectomy: how many patients may be eligible? Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:534–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathevet P, Laszlo de Kaszon E, Dargent D. Fertility preservation in early cervical cancer. Gynécol Obstét Fertil. 2003;31:706–12. doi: 10.1016/s1297-9589(03)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardini M, Barrett J, Seaward G, Covens A. Pregnancy outcome in patients post radical trachelectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1378–82. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wenzel L, Dogan-Ates A, Habbal R, Berkowitz R, Goldstein DP, Bernstein M, et al. Defining and measuring reproductive concerns of female cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;34:94–8. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter J, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR. Reproductive concerns of women treated with radical trachelectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter J, Sonoda Y, Chi DS, Raviv L, Abu-Rustum NR. Radical trachelectomy for cervical cancer: postoperative physical and emotional adjustment concerns. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monk BJ, Huang HQ, Cella D., III Quality of life outcomes from a randomized phase III trial of cisplatin with or without topotecan in advanced carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4617–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devins G, Orme C, Costello C. Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D). Psychol Health. 1998;2:139–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro F. EMDR: level 1 training manual. Pacific Grove; CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Events scale (IES): a measure of subjective distress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–18. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute Inc. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jose Pinheiro, Douglas Bates, Saikat DebRoy, Deepayan Sarkar, R Core team nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version. 2009;3:1–96. [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2009. pp. 3–900051-07-0. URL http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson EL, Wenzel LB, Osann K, Dogan-Ates A, Chantana N, Reina-Patton A, et al. Stress, immunity and cervical cancer: biobehavioral outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2111–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE. Randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1620–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter J, Raviv L, Applegarth L, Ford JS, Josephs L, Grill E, et al. A cross-sectional study of the psychosexual impact of cancer-related infertility in women: third-party reproductive assistance. J Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4(3):236–46. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]