Abstract

Studies suggest that primary extranodal follicular lymphoma (FL) is not infrequent but it remains poorly characterized with variable histologic, molecular, and clinical outcome findings. We compared 27 extranodal FL to 44 nodal FL using morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic techniques and evaluated the clinical outcome of these 2 similarly staged groups. Eight cases of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma were also studied. In comparison to nodal FL, a greater number of extranodal FL contained a diffuse growth pattern (P = 0.004) and lacked CD10 expression (P = 0.014). Fifty-four percent of extranodal and 42% of nodal FL cases showed evidence of t(14;18), with minor breakpoints (icr, 3′BCL2, 5′mcr) more commonly found in extranodal cases (P = 0.003). Outcome data showed no significant differences in overall survival (P = 0.565) and progression-free survival (P = 0.627) among extranodal, nodal, and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma cases. Analysis of all cases by t(14;18) status indicate that the translocation-negative group is characterized by a diffuse growth pattern (P = 0.043) and lower BCL2 expression (P = 0.018). The t(14;18)-positive group showed significantly better overall survival (P = 0.019) and disease-specific survival (P = 0.006) in comparison with the t(14;18)-negative group. In low stage FL, the status of t(14;18) seems to be more predictive of outcome than origin from an extranodal versus nodal site.

Keywords: follicular lymphoma; low stage; extranodal; t(14, 18); breakpoints; LMO2; HGAL

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most prevalent form of low grade B-cell lymphoma in adults in the United States. Although most FLs present with disseminated nodal involvement, primary extranodal FL is not infrequent. Most of the information regarding the frequency of primary noncutaneous extranodal FL is available from large studies evaluating all lymphoma subtypes occurring in specific extranodal locations. These studies suggest that primary extranodal FL comprises 1% to 38% of all primary lymphomas occurring at specific sites including 13% of female genital tract, 17% of testes, and 38% of duodenal lymphomas.6,8,9,14,17,18,32 Taken together, these studies suggest that certain extranodal sites have a relatively high frequency of involvement by primary FL.

The clinical outcome of extranodal FL has not been evaluated extensively. Previous studies suggest an indolent clinical course and prolonged survival for primary FL occurring in the gastrointestinal tract.25,32 Similarly, small studies of primary extranodal FL in the testis and salivary gland found a favorable outcome.3,16 However, these studies did not compare this disease to similarly staged nodal FL. The single study comparing outcome of 15 primary noncutaneous extranodal to 87 nodal FL found no difference in progression-free survival (PFS) or disease-specific survival (DSS).11 Of note, that study only included patients with stage I FL.11 In contrast to patients with stage III and IV FL, patients with stage II FL have a similar disease course to stage I FL and both are successfully treated with localized radiation therapy.1,19,28

The genetics of primary extranodal FL are also not well understood. Up to 95% of all FL contain a translocation between chromosomes 14 and 18, involving IGH at 14q32 and BCL2 at 18q2113. In contrast, variable rates of t(14;18) have been reported in primary extranodal FL presenting in different anatomic sites. In primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), which represents one of the best studied extranodal FL, the rate of t(14;18) varies from 0% to 51%.10,15,26,31 In 2 studies of primary gastrointestinal FL, this translocation was present in 15 of 18 cases.5,25 In contrast, an absent or low translocation rate was noted in FL presenting in the testis and salivary gland.3,16 In a study of primary noncutaneous extranodal FL, Goodlad et al11 found the translocation in only 2 of the 14 cases studied. The widely ranging rate of t(14;18) could indicate site-specific differences in primary extranodal FL.

As the IGH/BCL2 rearrangement is a relatively specific molecular marker of FL and has been used for diagnostic and disease monitoring purposes, it is important to establish its frequency in all subtypes of FL. To date, only 1 study has evaluated the frequency of t(14;18) in stage I FL.12 Goodlad et al found that among 47 patients with stage I FL, a subgroup exists that is characterized by a lack of t(14;18) with a predilection for extranodal sites and a better prognosis.10 However, that study included 15 PCFCL cases, which often lack t(14;18) and seem to be a unique disease group with a better outcome.

The aims of the current study are 2-fold. First, we characterize and compare stage IE and IIE extranodal with similar stage nodal FL. We use morphologic, immunohistologic, and molecular genetic techniques and compare the clinical course of these 2 disease groups. Second, we report the frequency of t(14;18) in these low stage patients. Although up to 30% of patients with FL present with low stage disease,2,24,27 the rate of t(14;18) in this subgroup has not been reported. We also evaluate the characteristics and clinical outcome of the t(14;18)-negative group with those of the t(14;18)-positive group. Finally, BCL6 translocations are evaluated to further characterize the pathogenesis of low stage FL.

METHODS

Case Selection

Seventy-one patients with stages I and II extranodal and nodal FL diagnosed between 1969 and 2007 at Stanford University and Palo Alto Veterans Hospital and Clinics with available materials, clinical follow-up, and staging information were identified for this study. Eight patients with PCFCL diagnosed between 1999 and 2007 with clinical outcome information were also included. Staging information was retrieved from a retrospective chart review. The staging evaluation included blood work, chest radiograph, and computed tomography scan. Additional studies included lymphangiography, ultrasonography, bone marrow biopsies, and bone scans. Patient data are summarized in Table 1. Within the extranodal FL group, only 5 of 27 cases were biopsies and the rest were considered excision specimens. This study has been approved by Stanford’s Institutional Review Board.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Case Characteristics in Noncutaneous Extranodal, Nodal, and Primary Cutaneous Follicular Lymphoma Patient Groups

| Extranodal | Nodal | Cutaneous | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 27 | 44 | 8 | 79 |

| Age (median) | 64 | 57 | 55 | |

| M:F | 14:13 | 27:17 | 5:3 | 46:33 |

| Sites | Colon (4) | Cervical (8) | Head and neck | |

| Duodenum (3) | Inguinal (12) | |||

| Stomach (1) | Axillary (7) | |||

| Small bowel (1) | Abdominal (11) | |||

| Parotid (6) | Supraclavicular (3) | |||

| Submandibular (2) | Colon (3) | |||

| Thyroid (2) | ||||

| Eye (4) | ||||

| Uvula (1) | ||||

| Testes (1) | ||||

| Ovary (1) | ||||

| Spleen (1) | ||||

| Stage | ||||

| I | 23 (85%) | 25 (60%) | N/A* | 48 |

| II | 4 (15%) | 19 (40%) | 23 | |

| Patients treated | 7 (35%) | 30 (71%) | 5 (62%) | 0.005 |

| Radiation (+/− chemotherapy) | 4 (57%) | 18 (60%) | 3 (60%) | |

| Radiation alone | 3 (43%) | 12 (40%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Transformed to | 1 (5%) | 6 (14%) | 0 | NS |

| DLBCL | ||||

| Relapse | 5 (25%) | 18 (43%) | 4 (50%) | NS |

Ann Arbor staging system is not applicable to PCFCL.

DLBCL indicates diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; PCFCL, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Nodal/Extranodal Definition

Lymphomas presenting in extranodal noncutaneous organs with no lymph node involvement (stage IE) or only minor local lymph node involvement (stage IIE) were considered eligible for this study. Clinically significant involvement of the surrounding nodal sites was considered as nodal FL. Lymphomas with localized lymph node involvement (stages I and II), and also those presenting in the tonsil, were considered nodal disease. Eight patients confirmed to have disease limited to the skin were also studied.

Histology

Grading was performed using the criteria of the 2001 World Health Organization (WHO) and 2005 WHO-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classifications.13,30 Noncutaneous FL cases with grade 3b morphology were excluded from this study. The lymphomas were graded independently and discrepant cases were reviewed by the authors (O.K.W. and D.A.A.) to arrive at a consensus. The follicular growth patterns were assigned using the WHO criteria.13

Immunohistochemical Studies

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded whole tissue sections as previously reported21–23 using the following antibodies: BCL6 (mouse monoclonal, prediluted, Cell Marque), BCL2 (mouse, 1:20, Cell Marque), CD3 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:200, Cell Marque), CD10 (mouse, 1:20, Novacastra), CD21 (mouse, 1:20, Dako), Ki-67 (mouse, 1:200, Dako), CD20 (mouse, 1:1000, Dako). Human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) and LMO2 staining was performed as previously described.25,26 Automated staining was performed on Dako and Ventana systems (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA; VentanaMedical Systems, Tucson, AZ). Tonsil tissue was used as positive controls and staining with omission of the primary antibody was performed as a negative control. The stains were scored on a scale of 0 to 4 based on the percentage of stained neoplastic cells: 0 = no cells stained, 1 = <25%, 2 = 25% to 50%, 3 = 50% to 75%, and 4 = >75%.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction Detection of t(14;18)

Genomic DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks or slides using DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacture’s protocol. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as previously reported29 with primers designed to detect MBR, mcr, icr, 3′BCL2, and 5′mcr breakpoints of the BCL2 gene.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Analysis

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed on unstained paraffin-embedded tissue sections with appropriate controls as previously reported29 using a dual color, dual fusion IGH/BCL2 translocation probe, and a dual color, break apart BCL6 probe.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval between the date of diagnoses and the date of death or last follow-up. DSS was defined as interval from diagnosis until death when the underlying cause of death was lymphoma or treatment toxicity, with all other causes of death censored. PFS was defined as the time interval between the date of initial diagnosis and the date of disease progression or death from any cause, whichever came first, or date of last follow-up. Patients who were not initially treated were excluded from the PFS analysis. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier methods and compared using the log-rank test. Followup information was obtained from medical records and included response to therapy based on the Cheson et al criteria.4 Variables were compared using χ2 test and Mann-Whitney U test. SPSS version 13 was used for all analysis.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemical Analysis

The distribution of grade and growth pattern in extranodal FL, nodal FL, and PCFCL is summarized in Table 2. The architecture was easily assessed in all cases within 3 groups. Growth pattern was determined on hematoxylin and eosin slide and confirmed with a CD21 stain. Although the grade distribution was similar, the extranodal FL was more likely to exhibit a predominantly diffuse pattern as compared with nodal FL and PCFCL (P = 0.004). There was no correlation between grade and growth pattern (P = 0.969). Among cases with diffuse growth pattern, most were grade 1 (12/20, 60%), as compared with grade 2 (4/20, 33%) and grade 3 (4/20, 33%).

TABLE 2.

Histologic and Immunohistochemical Comparison Between Noncutaneous Extranodal, Nodal, and PCFCL

| Extranodal N = 27 (%) |

Nodal N = 44 (%) |

PCFCL N = 8 (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | ||||

| 1 | 17 (63) | 26 (59) | 4 (50) | NS |

| 2 | 6 (22) | 9 (20) | 1 (12) | |

| 3a | 4 (15) | 9 (20) | 3 (38) | |

| Growth pattern | ||||

| Follicular | 11 (41) | 33 (75) | 3 (38) | 0.004 |

| Follicular and diffuse | 2 (7) | 7 (16) | 3 (38) | |

| Focally follicular (diffuse) | 14 (52) | 4 (9) | 2 (24) | |

| Immunopositive cases* | ||||

| CD10 | 18 (67) | 39 (89) | 3 (38) | 0.014 |

| BCL2 | 24 (89) | 34 (77) | 3 (38) | NS |

| BCL6 | 25 (93) | 43 (98) | 8 (100) | NS |

| Ki-67 (median %) | 10 | 20 | 20 | NS |

| LMO2 | 27 (100) | 43 (98) | 8 (100) | NS |

| HGAL | 27 (100) | 43 (98) | 8 (100) | NS |

Cases scored as 1 and above were considered as immunopositive.

HGAL indicates human germinal center-associated lymphoma; PCFCL, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

The diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma was confirmed with a CD20 stain. Scattered T cells were highlighted with CD3 and tended to concentrate in the interfollicular areas. We used a Ki-67 stain to measure the proliferation index on whole sections. Although the proliferation index did not vary significantly among extranodal, nodal, and PCFCL groups (Table 2), it showed a linear correlation with grade (P = 0.036).

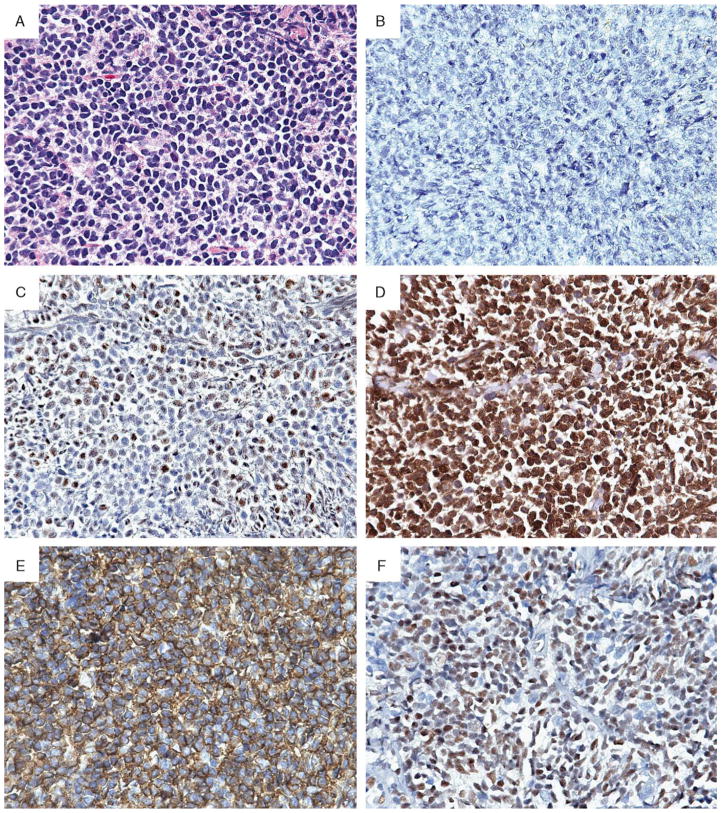

The fraction of patients that were CD10-negative was significantly higher among extranodal (9/27, 33%) as compared with nodal FL (5/44, 11%) (P = 0.012). An example of a CD10-negative extranodal FL is shown in Figure 1B. Positive internal control, which included staining of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, granulocytes, was present in all of CD10-negative cases. Among the CD10-positive cases, the number of CD10-positive neoplastic cells was higher in the nodal as compared with the extranodal FL (P = 0.005). In contrast to nodal FL, most of the PCFCL (5/8, 63%) cases were CD10-negative. Thus, similar to PCFCL, extranodal FL cases were significantly more likely to be CD10-negative as compared with nodal FL (Table 2). Comparison of CD10 staining with growth pattern in all 3 FL groups showed a significant correlation of absence of CD10 expression with a diffuse growth pattern (P = 0.01). However, within the extranodal FL group, no significant correlation of CD10 staining with growth pattern was seen (P = 0.095).

FIGURE 1.

Typical case of primary extranodal follicular lymphoma that presented in the colon (H&E, A) and showed the following staining pattern: negative for CD10 (B), but demonstrated nuclear BCL6 (C) and BCL2 (D) protein expression. Newer germinal center markers were evaluated, including HGAL (E) with a strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining and LMO2 (F) with a nuclear staining pattern (all magnifications 600×).

Although a greater number of nodal FL cases lacked BCL2 protein expression (10/44, 23%) as compared with extranodal FL (3/27, 11%), this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2, Fig. 1D). In addition, the number of BCL2-positive neoplastic cells was not significantly different between the extranodal and nodal groups (P = 0.354). In the PCFCL group, 5/8 cases (63%) lacked BCL2 coexpression. Thus, in contrast to PCFCL, primary extranodal and nodal FL demonstrated a similar frequency of expression of BCL2 protein.

HGAL is a newly characterized germinal center B-cell marker.22 The majority of cases studied (78/79, 98% cases) exhibit strong cytoplasmic staining of both the follicular and interfollicular neoplastic cells for HGAL (Fig. 1E). The number of neoplastic cells stained for HGAL was similar between extranodal, nodal, and PCFCL. We also evaluated LMO2, a cysteine-rich LIM domain-containing transcription factor.23 The majority of the cases (78/79, 98%) showed nuclear staining of the follicular and inter-FL cells (Fig. 1F). A comparison of extranodal, nodal, and PCFCL cases showed no difference in the number of neoplastic cells stained (P = 0.275).

The neoplastic cells in the majority of nodal, extranodal, and PCFCL cases demonstrated nuclear staining for BCL6 protein (Table 2, Fig. 1C). No significant difference was noted in the number of neoplastic cells stained for BCL6 between extranodal, nodal, and PCFCL cases (P = 0.194).

Frequency of BCL2 Breakpoints and FISH Results

Seventy-four cases were studied for 5 IGH/BCL2 translocation breakpoints using real-time PCR and the results are summarized in Table 3. Screening for translocations in BCL2 using MBR primers demonstrated the presence of a breakpoint in 24 patients. The minor breakpoints included: icr in 12 cases (33%), 3′BCL2 in 6 (17%), and 5′mcr in 1 case (1%). Correlation with the location showed that breakpoints occurred in the MBR region with a similar frequency in all 3 subgroups, however, the minor breakpoints were more prevalent in extranodal FL (P = 0.003). No breakpoints were detected in the remaining 38 cases (51%).

TABLE 3.

Summary of the Molecular Findings in the Noncutaneous Extranodal, Nodal, and PCFCL Patient Groups*

| Extranodal FL N = 26 (%) |

Nodal FL N = 40 (%) |

PCFCL N = 8 (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBR | 8 (31) | 13 (32) | 3 (38) | NS |

| mcr | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| 3′BCL2 | 4 (15) | 1 (2) | 1 (12) | 0.04 |

| 5′mcr | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | NS |

| icr | 7 (26) | 4 (10) | 1 (12) | 0.048 |

| Total PCR+ | 14 (54) | 17 (42) | 5 (63) | NS |

| t(14;18) − | 12 (46) | 23 (58) | 3 (37)† | NS |

| BCL6 translocation | 1 (4) | 3 (8) | N/A | NS |

Eight cases contained double breakpoints.

One PCFCL cases was t(14;18)-negative by PCR but did contain translocation by FISH.

FISH indicates fluorescence in situ hybridization; FL, follicular lymphoma; PCFCL, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

The 38 PCR-negative cases were tested for IGH/BCL2 translocations using FISH. Of the 38 PCR-negative cases, 1 PCFCL case contained t(14;18). All 74 cases were evaluated by FISH for the presence of BCL6 translocations (Table 3). Four cases (5%) contained BCL6 translocations and one of these also contained an IGH/BCL2 rearrangement. Of the 4 patients with BCL6 translocation, 3 had nodal and 1 had extranodal FL.

Analysis of Immunohistochemical Data by t(14;18) Status

Using PCR and FISH methods, the overall frequency of t(14;18) was low in this study, present in 36/74 (49%) of all cases. On the basis of the PCR and FISH results, the cases were divided into 2 groups, t(14;18)-positive and t(14;18)-negative, and compared using the same analysis as described above. Although the grade distribution was similar in both groups (P = 0.363), there were differences in growth pattern with a predominance of a diffuse pattern in t(14;18)-negative cases (P = 0.043, Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of t(14;18) Positive and Negative Groups

| t(14;18)+ N = 36 (%) |

t(14;18)− N = 38 (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | |||

| 1 | 22 (61) | 21 (57) | NS |

| 2 | 9 (25) | 6 (15) | |

| 3a | 5 (14) | 11 (28) | |

| Growth pattern | |||

| Follicular | 25 (69) | 18 (49) | 0.043 |

| Follicular and diffuse | 5 (14) | 7 (18) | |

| Focally follicular (diffuse) | 6 (17) | 13 (33) | |

| Immunopositive | |||

| CD10 | 28 (78) | 27 (71) | NS |

| BCL2 | 32 (89) | 27 (71) | 0.018 |

| BCL6 | 35 (97) | 37 (97) | NS |

| Ki-67 (median %) | 10 | 20 | NS |

| LMO2 | 36 (100) | 37 (97) | NS |

| HGAL | 36 (100) | 38 (100) | NS |

The immunohistologic staining patterns of the translocation positive and negative groups was also compared (Table 4). Fewer cases showed BCL2 protein expression in the t(14;18)-negative group as compared with t(14;18)-positive group (P = 0.018). In addition, fewer BCL2 positive neoplastic cells were present in the t(14;18)-negative group (P = 0.03). Excluding the PCFCL cases from analysis by translocation status led to a similar finding: t(14;18)-negative cases were associated with decreased BCL2 protein expression (P = 0.012). Thus, the FL cases with t(14;18) more frequently expressed BCL2 protein. The remaining stains did not vary with translocation status.

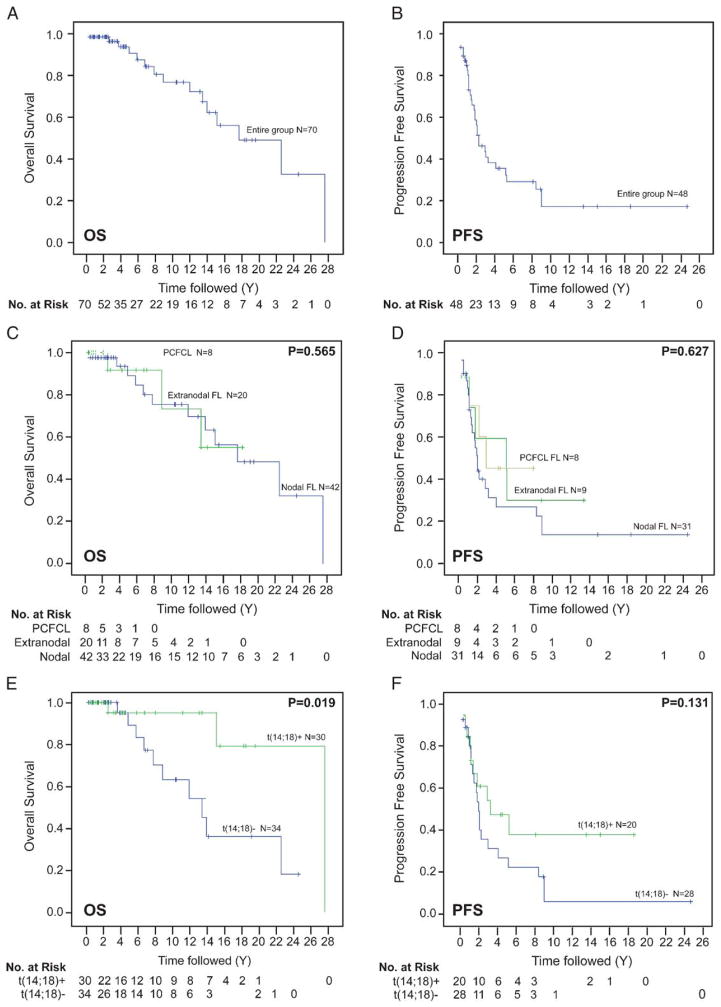

Clinical Outcome

Clinical follow-up information was available for 20 patients with extranodal FL, 42 with nodal FL, and 8 with PCFCL (Figs. 2A, B). Although more patients with primary extranodal FL (17/20) and PCFCL (8/8) were alive at last follow-up as compared with nodal FL (30/42), this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.56). Transformation to a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurred in 1 of 20 (5%) extranodal FL, 6 of 42 (14%) nodal FL, and no PCFCL patients (P = 0.335). Treatment was given to 7 of 20 (35%) extranodal FL, 30 of 42 (71%) nodal FL, and to 5 of 8 (62%) PCFCL patients (Table 1). In the 12 patients who were not initially treated, time to first treatment was 4.3 years and the remaining 16 patients continued to be observed.

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival (OS, A) and progression-free survival (PFS, B) in the entire group. Analysis of OS (C) and PFS (D) by extranodal, nodal, and PCFCL groups shows no significant differences (P = 0.565, P = 0.627). Analysis of OS (E) and PFS (F) by t(14;18)−status shows better OS and trend for longer PFS than in t(14;18)+ cases (P = 0.019, P = 0.131). PCFCL indicates primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

As compared with nodal FL, treated patients with primary extranodal FL had shorter PFS, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.192). The OS and DSS were similar between primary extranodal and nodal FL groups (P = 0.972 and 0.480). A comparison of primary extranodal, nodal, and PCFCL groups also showed no significant differences in PFS, OS, or DSS (P = 0.565, P = 0.627, and P = 0.722; Figs. 2C, D). Further separating patients into 4 groups, including extranodal, gastrointestinal, nodal, and PCFCL did not reveal significant differences in OS, DSS, or PFS (P = 0.395, P = 0.678, P = 0.566).

Comparing outcome according to t(14;18) status revealed that those patients with the translocation had longer OS and DSS as compared with those without (P = 0.019 and P = 0.006, Fig. 2E). The mean OS in t(14;18)-positive patients was 24.5 years (95% confidence interval, 19.4–29.6 y), whereas it was 14.5 years (95% confidence interval, 10.6–18.4 years) in the t(14;18)-negative group. Furthermore, a trend toward longer PFS was present in t(14;18)-positive FL patients though this was not statistically significant (P = 0.131, Fig. 2F). Excluding the PCFCL cases from this analysis did not change the findings: the t(14;18)-positive patients showed longer OS and DSS as compared with t(14;18)-negative patients (P = 0.024 and P = 0.008). Excluding patients with noncutaneous grade 3 FL from this analysis also did not change the findings: OS and DSS of patients with t(14;18) was significantly longer as compared with t(14;18)-negative patients (P = 0.016 and P = 0.003).

Analysis of OS, DSS, and PFS by histologic grades showed no significant differences (P = 0.671, P = 0.158, P = 0.703). Analysis of OS by FL growth pattern showed that patients with a diffuse pattern had a worse OS and trend for shorter DSS as compared with those with predominantly follicular or a mixture of follicular and diffuse patterns (P = 0.002, P = 0.059); however, no differences in PFS was seen in these 3 groups (P = 0.871). Comparison by stage showed that stage I FL had similar OS, DSS, and PFS as stage II FL (P = 0.811, P = 0.973, P = 0.946).

DISCUSSION

FL is one of the most prevalent lymphoma types in Western countries. Primary extranodal FL is less common, with reported frequencies ranging from 1% to 38%.6,8,9,14,17,18,32 Whereas much is known about PCFCL, primary noncutaneous FL remains poorly characterized with variable histologic, molecular, and clinical outcome findings. In the largest study to date of primary extranodal FL, Goodlad et al11 found that 5 of 15 cases had a diffuse growth pattern and only 9 of 15 expressed BCL2; however, a histologic and immunohistochemical comparison to a similar stage nodal FL was not made. By comparing 27 primary extranodal to 44 nodal FL, we confirm in a larger series of extranodal FL that these exhibit a diffuse growth pattern. In contrast, our extranodal FL cases are more often CD10-negative although no differences in BCL2 protein expression were seen. Furthermore, no correlation of CD10 expression and growth pattern is present within our extranodal FL group. This difference in immunohistologic patterns could be due to inclusion of patients with stage II FL. However, comparison of stage I to stage II cases in our series showed no significant differences in grade, growth, or immunohistologic patterns.

To characterize the molecular differences in low stage FL, we studied 74 cases using PCR and FISH analyses. Although both extranodal and nodal FL contained t(14;18) in similar frequency, a significantly higher number of minor breakpoints are present in extranodal FL. The most common minor breakpoint was icr, present in 12/74 (16%) of all cases and in 8/26 (31%) of extranodal cases. These findings are consistent with what we previously reported in 236 FL cases, where icr comprised 13% of all cases.29 Importantly, this finding implies that the standard PCR primers currently used by many laboratories that target only MBR will fail to detect the translocation in a significant proportion of low stage FL cases.

Our results demonstrate a low rate of t(14;18), which was present in only 38/74 (51%) of patients with low stage FL. Using a similar PCR and FISH approach, we recently found this translocation in 222 of 236 (94%) of patients with advanced stage FL.29 Thus, this difference in frequency of t(14;18) is likely related to the stage of the disease at presentation. The absence of t(14;18) in stage I FL has also been recently reported by Goodlad et al.12 On the basis of their findings, Goodlad et al proposed a subtype of FL that lacks t(14;18), has lower BCL2 and CD10 expression and occurs more often in extranodal sites.12 Though we also find decreased BCL2 expression in t(14;18)-negative cases, no differences in CD10 expression or extranodal presentation are identified. Furthermore, excluding stage II and PCFCL cases from our cohort did not change the results. Thus, the t(14;18)-negative cases in our study differ from t(14;18)-positive FL by exhibiting a diffuse growth pattern and decreased expression of BCL2 protein.

The differential diagnosis of t(14;18)-negative FL includes follicular colonization by marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Most of the t(14;18)-negative FL cases (37/38, 97%) in our study show expression of BCL6 protein by the neoplastic lymphoma cells. A recent study by Dogan et al7 showed that most cases of FL (34/36, 94%) expressed BCL6 whereas all marginal zone lymphomas were BCL6 negative (0/10, 0%). Moreover, Naresh20 evaluated nodal marginal zone lymphomas with prominent follicular colonization and also noted that in all cases the neoplastic cells were BCL6 negative. These studies suggest that BCL6 is a sensitive marker for follicle center derivation. In addition, the newer germinal center markers utilized in this study, LMO2 and HGAL highlighted most of our cases (37/38, 94% and 38/38, 100% respectively), providing further support for t(14;18)-negative FL.

Our clinical outcome data shows that t(14;18)-negative low stage FL have significantly worse OS, DSS, and trend for shorter PFS as compared with t(14;18)-positive cases. In contrast, Goodlad et al12 found that t(14;18)-negative cases had a better OS and PFS in their study of 47 stage I FL cases. The difference could be due to inclusion of patients with stage II FL in our study. However, comparison of stages I and II FL shows no difference in OS or PFS. Furthermore, the distribution of stage II is similar in 2 groups, with stage II cases comprising 26% of t(14;18)-negative and 29% of t(14;18)-positive groups.

In summary, this is the largest study to date comparing similarly staged extranodal and nodal FL. We found that similar to PCFCL, extranodal FL contains a diffuse growth pattern and decreased CD10 protein expression. An unexpectedly high number of low stage FL lack t(14;18) and these cases have decreased BCL2 protein expression. Importantly, the t(14;18) status seems to predict OS, DSS, and PFS better than extranodal versus nodal status in low stage FL.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Pathology, Stanford University. Research performed at Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford Comprehensive Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Advani R, Rosenberg SA, Horning SJ. Stage I and II follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: long-term follow-up of no initial therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1454–1459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2780–2795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacon CM, Ye H, Diss TC, et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the testis and epididymis in adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1050–1058. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802ee4ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damaj G, Verkarre V, Delmer A, et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 25 cases and a literature review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:623–629. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the thyroid gland: a clinicopathologic study of 108 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:623–639. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dogan A, Bagdi E, Munson P, et al. CD10 and BCL-6 expression in paraffin sections of normal lymphoid tissue and B-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:846–852. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferry JA, Harris NL, Young RH, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the testis, epididymis, and spermatic cord. A clinicopathologic study of 69 cases with immunophenotypic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:376–390. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferry JA, Fung CY, Zukerberg L, et al. Lymphoma of the ocular adnexa: a study of 353 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:170–184. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213350.49767.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodlad JR, Krajewski AS, Batstone PJ, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 16 cases in support of a distinct entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:733–741. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodlad JR, MacPherson S, Jackson R, et al. Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Group. Extranodal follicular lymphoma: a clinicopathological and genetic analysis of 15 cases arising at non-cutaneous extranodal sites. Histopathology. 2004;44:268–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodlad JR, Batstone PJ, Hamilton DA, et al. BCL2 gene abnormalities define distinct clinical subsets of follicular lymphoma. Histopathology. 2006;49:229–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe ES, Stein H, Vardiman DW, et al. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001. p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kempton CL, Kurtin PJ, Inwards DJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the bladder: evidence from 36 cases that low-grade lymphoma of the MALT-type is the most common primary bladder lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1324–1333. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim BK, Surti U, Pandya A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular cytogenetic fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of primary and secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:69–82. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146015.22624.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kojima M, Nakamura S, Ichimura K, et al. Follicular lymphoma of the salivary gland: a clinicopathological and molecular study of six cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2001;9:287–293. doi: 10.1177/106689690100900405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kojima M, Shimizu K, Nishikawa M, et al. Primary salivary gland lymphoma among Japanese: a clinicopathological study of 30 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1793–1798. doi: 10.1080/10428190701528509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosari F, Daneshbod Y, Parwaresch R, et al. Lymphomas of the female genital tract: a study of 186 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1512–1520. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000178089.77018.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mac Manus MP, Hoppe RT. Is radiotherapy curative for stage I and II low-grade follicular lymphoma? Results of a long-term follow-up study of patients treated at Stanford University. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1282–1290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naresh KN. Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma with prominent follicular colonization—difficulties in diagnosis: a study of 15 cases. Histopathology. 2008;52:331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natkunam Y, Soslow R, Matolcsy A, et al. Immunophenotypic and genotypic characterization of progression in follicular lymphomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2004;12:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natkunam Y, Lossos IS, Taidi B, et al. Expression of the human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) protein, a new marker of germinal center B-cell derivation. Blood. 2005;105:3979–3986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natkunam Y, Zhao S, Mason DY, et al. The oncoprotein LMO2 is expressed in normal germinal-center B cells and in human B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2007;109:1636–1642. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plancarte F, López-Guillermo A, Arenillas L, et al. Follicular lymphoma in early stages: high risk of relapse and usefulness of the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index to predict the outcome of patients. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shia J, Teruya-Feldstein J, Pan D, et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinical and pathologic study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:216–224. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streubel B, Scheucher B, Valencak J, et al. Molecular cytogenetic evidence of t(14;18)(IGH;BCL2) in a substantial proportion of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:529–536. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104:1258–1265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK. Low Grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberg OK, Ai WZ, Mariappan MR, et al. “Minor” BCL2 breakpoints in follicular lymphoma: frequency and correlation with grade and disease presentation in 236 cases. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:530–537. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang B, Tubbs RR, Finn W, et al. Clinicopathologic reassessment of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with immunophenotypic and molecular genetic characterization. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:694–702. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshino T, Miyake K, Ichimura K, et al. Increased incidence of follicular lymphoma in the duodenum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:688–693. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]