Abstract

Context:

There is a lack of evidence on the subjective aspects of the provider perspective regarding diabetes and its complications in India.

Objectives:

The study was undertaken to understand the providers' perspective on the delivery of health services for diabetes and its complications, specifically the eye complications in India.

Settings and Design:

Hospitals providing diabetic services in government and private sectors were selected in 11 of the largest cities in India, based on geographical distribution and size.

Methods:

Fifty-nine semi-structured interviews conducted with physicians providing diabetes care were analyzed all interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated. Nvivo 10 software was used to code the transcripts. Thematic analysis was conducted to analyze the data.

Results:

The results are presented as key themes: “Challenges in managing diabetes patients,” “Current patient management practices,” and “Strengthening diabetic retinopathy (DR) services at the health systems level.” Diabetes affects people early across the social classes. Self-management was identified as an important prerequisite in controlling diabetes and its complications. Awareness level of hospital staff on DR was low. Advances in medical technology have an important role in effective management of DR. A team approach is required to provide comprehensive diabetic care.

Conclusions:

Sight-threatening DR is an impending public health challenge that needs a concerted effort to tackle it. A streamlined, multi-dimensional approach where all the stakeholders cooperate is important to strengthening services dealing with DR in the existing health care setup.

Keywords: Diabetes, diabetes retinopathy, health system response, India, providers perspective

INTRODUCTION

There is a global epidemic of diabetes. About 382 million people live with diabetes (8.3% of the world's adult population in 2013) and by 2035, this will have increased by 55% to 592 million.[1] Many emerging economies contribute to this global epidemic. According to a study conducted by the Indian Council for Medical Research in 2011, India has 62.4 million people with type 2 diabetes.[2] It is further projected by the International Diabetes Federation that by 2030, this will increase to 100 million.[1]

Studies in different parts of the country reveal a high and increasing prevalence in both urban and rural areas, with a higher prevalence being reported from urban areas. Most of this evidence comes from South and Central India. In South India, the prevalence of diabetes among adults is estimated to be around 20% in urban areas and nearly 10% in rural areas.[3] As the epidemic matures and diabetics live longer, the cardiovascular, renal, and ocular complications will increase, imposing a burden on health care facilities.[4]

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a major microvascular complication of diabetes, has a significant impact on the World's Health Systems. According to an estimate, the number of people with DR will grow from 126.6 million in 2010 to 191.0 million by 2030. If this is not addressed appropriately, it is further projected that sight-threatening DR (STDR) will increase from 37.3 million to 56.3 million.[5]

An estimated 6 million diabetics in India have STDR. If the proportion of diabetics STDR remains the same over time, the number will increase to over 10 million by 2035.

The broad aims of the study were to understand the provider perspective on the delivery of health services for diabetes and its complications, specifically the eye complications in India. This paper focuses on providers' perspectives on diabetes and DR and strengthening health systems responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics

The study was granted ethics approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Indian Institute of Public Health (IIPH), Hyderabad, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK.

Study design

The study was conducted in the most populated cities across India, representing different geographic regions of the country. Sampling entailed a two-stage process. Initially, cities were ranked in descending order of population size (2011 census) and the 10 most populated cities Ahmedabad, Bengaluru, Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, Mumbai, Pune, and Surat - were selected. To address lesser representation from Eastern India, Bhubaneswar was added, making the sample a total of 11 cities.

Detailed methodology adopted is described in a companion paper in this issue.

After obtaining approval from senior managers, semi-structured interviews were conducted with clinicians, counselors, and dieticians working in these hospitals. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by a team of investigators from IIPH Hyderabad. Interviews were recorded after taking consent from the respondents.

Data analysis

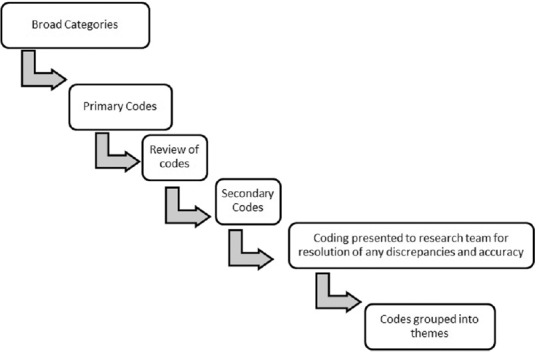

All the interviews were transcribed into English. Thematic analysis was conducted with the data from the semi-structured interviews [Figure 1]. Initial apriori codes were developed from the interview guide. The codes were refined in discussions with the researchers who conducted the interviews. Nvivo 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to code the interview transcripts. Emergent codes were identified through an iterative engagement with the data.

Figure 1.

Method of developing codes and thematic content

RESULTS

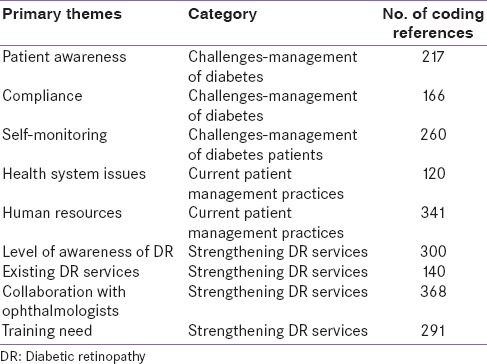

The results presented here are from the analysis of 59 interviews conducted with senior physicians and endocrinologists across the study sites. The data were classified as 9 primary codes and 40 secondary codes. These codes were organized into 3 themes: (1) Challenges in managing diabetes patients; (2) current patient management practices; and (3) strengthening DR services at the health systems level. An overview of primary codes and their frequency is presented in Table 1, and illustrative quotes for the three themes and respective codes are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Frequency of primary themes and codes

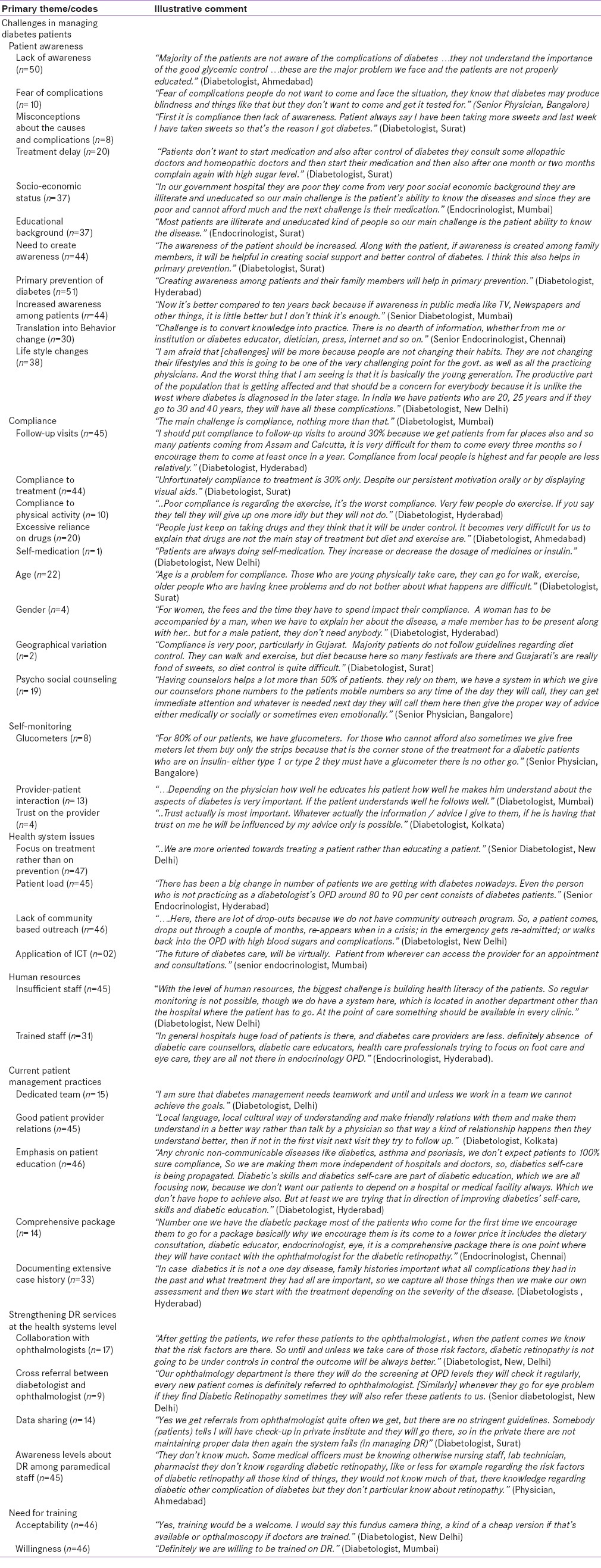

Table 2.

Tabulation of primary themes and codes with illustrative comments

Key overlapping issues, such as change over time in various aspects of diabetes, are discussed in a separate section.

Theme 1: Challenges in managing diabetes patients

In this section, challenges faced by the health professionals regarding the treatment and management of diabetic patients are presented. The data are structured around 4 subthemes: (1) Patient awareness, (2) compliance, (3) self-monitoring, and (4) health system issues.

Patient awareness

Service providers emphasized the lack of awareness about diabetes and its complications as a key challenge for self-management among the patients. The level of awareness of the patients was related to socioeconomic and educational background of the patients. Awareness levels were lower among the poor and less educated patients. Lack of awareness included misconceptions about the cause and fear of complications caused by diabetes. Lack of awareness leading to fear of complications was identified as a deterrent for seeking early diagnosis and treatment for diabetes among most of the patients.

However, participants reported better awareness among patients from urban area resulting in better screening and treatment. Improving awareness among the patients and their family members were also identified as an important strategy for the primary prevention of diabetes. Respondents opined that increased awareness could translate into health behavioral change and create social support systems for coping with the condition. For example, one of the physicians stated: “Awareness of the patient should be increased. Along with the patient, if awareness is created among family members, it will be helpful in creating social support and better control of diabetes. I think this also helps in primary prevention.”

Compliance

A majority of the practitioners identified compliance as a critical factor in self-management of diabetes and associated conditions. Socioeconomic background of the patients and misconceptions about diabetes resulted in poor acceptance of diagnosis and compliance with medication and lifestyle changes. According to one of the participants, “patients complied better with medication than with life style changes, such as dietary modifications and physical exercise.”

Participating health providers identified the following factors that influenced compliance:

Provider - patient interactions resulting in trust on the provider. According to a diabetologist, “trust influenced the extent to which the information received by the patient is translated into effective compliance and self-care”

Socioeconomic status of patients impacts their ability to bear the costs of disease monitoring and making life style modifications. Compliance was found to be poor among patients dependent on daily wages for their livelihood

However, some practitioners reported that compliance to medication was better among patients accessing government services. Practitioners in the private sector assessed the financial status of patients and accordingly prescribed medicines, as there is a large variation in prices of the diabetes drugs

The age of the patient influenced lifestyle changes and motivation to manage their condition. Younger patients were more able to make life style modifications compared to older patients who had age-related musculoskeletal impairments

The gender of patients also influences compliance with follow-up visits and care. Men who sought medication from the government sector had a problem complying with follow-up visits and treatment as the distribution of free drugs is during working hours. Therefore most men who work do not comply with follow-up visits and medication, whereas women, many of whom were home makers, could visit the hospital independently to collect their free medicines

Costs associated with the follow-up visits, the need for a male to accompany them and time required for the tests affect female's management

Compliance with dietary change is influenced by geographical location where culture specific dietary practices and varieties of food items consumed vary

It was reported that compliance to follow-up visits is largely dependent on the distances patients travel to seek treatment.

Self-monitoring

To encourage compliance, some practitioners were promoting self-monitoring of blood glucose. Decreasing cost and ease of checking blood sugar levels with a glucometer are said to have changed the scenario of self-management of diabetes. Interventions such as psychosocial counseling and medical counseling by trained counselors who were accessible by phone and a 24-h help line and telephone were reported to have increased compliance.

Health system issues

Excessive focus on treatment rather than prevention was identified as a reason for low awareness about diabetes and its complications. A burgeoning middle class is contributing to an exponential rise in the number of diabetes cases in India. A lack of policy attention on the rise of the middle class and the changing disease pattern was highlighted.

Increasing incidence of diabetes was identified as a challenge for the health system as it increased the patient load on the burdened health system. Paucity of human resources and lack of understanding among the care providers were contributing to the burden on the health system.

Theme II: Current patient management practices

Varied sets of practices were reported across different facilities. Few salient findings were:

Some hospitals reported efforts to establish good patient-provider relationship and patient management. They recruited a team of counselors, educators, and physician assistants who communicated with the patients in the local language and in a culturally sensitive way

Some diabetologists and hospitals emphasized on patient education on holistic self-management rather than promoting dependence on only medical management

Some hospitals in the private sector offered a comprehensive package to the 1st time patients, including consultation with an endocrinologist, dietician, and a health educator

Documentation of extensive case history of the 1st time patients was mentioned to be very helpful in effective assessment and management of diabetes in the later stages

High patient load in the government hospitals and shortage of human resources were identified as challenges for managing patients in a government setting. Staff nurses and councilors provided information to the patient on life style modifications required for managing diabetes. Patients collected free diabetic medication for every 15 days. Due to the patient load, consultation with a doctor was only possible once in 6 months. Most of the times complications related to diabetes were self-reported by the patients

Some private clinics, due to the absence of dieticians and counselors focused on medical management of diabetes with some basic advice on lifestyle modification

Practitioners were increasingly depending on technological aids such as glucometers for promoting self-management of diabetes. Some hospitals were providing these machines at subsidized rates and sometimes at free of cost for the benefit of patients who cannot afford them for a regular monitoring of the blood sugar levels.

Upon querying about diabetes management, respondents mentioned that it was important to innovate in managing diabetes. Some of the key findings on diabetes management among the patients were:

Importance of a team approaches among the health professionals in managing diabetes

Establishing a peer network among the patients

Lifestyle modification was identified as an important factor in managing diabetes. Changing food habits due to westernization and other life style changes such as sleep pattern, physical activity, and lack of preventive outlook in Indian society impact diabetes management

Owing to its asymptomatic nature, detection of diabetes is delayed in majority of the cases. Added to this, stigma and general reluctance of high-risk people with family history of diabetes are reasons for delay in self-screening

Frequent shifting from one health provider to the other, increasing the number of both trained and untrained health practitioners claiming to be specialists in diabetes treatment were identified as emerging challenges in diabetes management.

Theme III: Strengthening diabetic retinopathy services

The extent of services provided for DR varied across the hospitals.

Some hospitals initiated a system where a general physician did the initial screening for DR. Later, a fundus camera was used to take images of retina in patients with advanced retinopathy. Then the ophthalmologist was consulted for further analysis.

In some hospitals, annual retinal check-up system was institutionalized to monitor the retina complications among the diabetic patients.

Some hospitals were using internet to send the pictures of the fundus to an ophthalmologist who then sent an email with his observation. Patient was given a printed report about the status of their eye for further follow-up.

To understand the services better, the findings are presented in the following sections.

Collaboration with ophthalmologists

To document the existing practices of collaboration between the diabetologist and ophthalmologists, respondents were asked about the referral practices:

Some clinicians preferred to manage the risk factors before referring the patients to ophthalmologists as they thought it was critical to address these to control DR

In some large hospitals with ophthalmology section, diabetologist and ophthalmologists cross-referred patients

As not all diabetes patients require DR examination, some hospitals institutionalized need-based online collaboration with ophthalmologists.

Data sharing between the private and government hospitals were highlighted as a contentious issue that influenced collaboration and cross-referrals among diabetologists and ophthalmologists.

Existing level of awareness on diabetic retinopathy

Most practitioners mentioned that the awareness levels among the paramedical staff in the hospitals such as nurses, lab technicians, and pharmacists regarding DR were low.

However, some practitioners were not sure about the levels of awareness among the staff in their hospitals.

Training need: Respondents were of opposing opinions on the need for diabetic retinopathy training for the health staff

Most of the practitioners interviewed mentioned that training the staff on DR is welcome. In hospitals where ophthalmology units were established, diabetologists were open to training as it helps them in screening patients

Some physicians were of the opinion that the training will help them enhance their knowledge, but expert ophthalmologists should be consulted for more careful examination

Some of the practitioners in the hospitals were reluctant to get trained on DR, citing reason that they are already trained and at most a short-term refresher courses could be organized for them

Some practitioners did not think that diabetologists be trained on DR. They felt that Ophthalmology Department should take the lead on DR

Some felt that additional training for diabetologists will add to their existing burden and hinder the provision of comprehensive care to the patients

Some practitioners categorically denied any need for training the staff on DR as it was felt that it requires professional assessment

Short-term training ranging 3–5 h was mentioned to be more effective than long-term training

A streamlined, multi-dimensional approach where all the stakeholders cooperate in treating diabetes and complications was suggested to strengthening services deal with DR in the existing health care setup

Education of the patients, health professionals including nurses and general physicians was suggested as a way forward to deal with the increasing number of diabetes students.

DISCUSSION

This study presents the perspectives of health providers on the scope for strengthening DR services in India. It suggests that many factors influence the management of diabetes and its complications in India. These factors are in consonance with what has been described from India in the recent past.[6,7,8]

The diabetic care providers managing the treatment of persons with diabetes and DR opined that the socioeconomic background of the clients with diabetes and their awareness levels were critical determinants in their willingness and ability to comply with medications, lifestyle changes, and long-term follow-up required for effective management. Similar findings regarding the impact of socioeconomic status of clients on treatment compliance have been reported earlier.[8,9,10] Physicians suggested that the awareness should be created among the family members along with the patients for better management of diabetes.

Self-management was identified as an important prerequisite for dealing with diabetes and resultant complications. Lifestyle interventions are a key to management of diabetes and its complications.[11] A study from China has highlighted the role of awareness and practices of self-management on type 2 diabetes.[12] The need to move beyond conventional hospital based management of diabetes and complications was suggested. The role of diagnostic and technological advancements and enhanced access to glucometers, application of information and communication technology in the provision of care, nonmydriatic fundus camera were identified as important in the effective management of DR in the future. The use of fundus photography for screening has now found widespread acceptance in many countries.[13,14,15]

The awareness level of hospital staff other than the clinicians on DR was found to be inadequate. Though most of the respondents welcomed training on DR, it was felt that a team approach that includes an ophthalmologist would be more productive in providing comprehensive diabetic care to the patients.

The findings from this study provide insight into the provider's perspectives on the strengthening DR services in India. The selection of the providers from different institutes across key cities of the country, in-depth interviews and coding process are the strengths of this study. A key limitation is that a comparative analysis of perspectives from ophthalmologists was not conducted.

Financial support and sponsorship

Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by a grant from the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust, London, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:137–49. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Sudha V, Unnikrishnan R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) in urban and rural India: Phase I results of the Indian Council of Medical Research-INdia DIABetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3022–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Diabetes in South Asians: Is the phenotype different? Diabetes. 2014;63:53–5. doi: 10.2337/db13-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaveeshwar SA, Cornwall J. The current state of diabetes mellitus in India. Australas Med J. 2014;7:45–8. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2013.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y, He M, Congdon N. The worldwide epidemic of diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:428–31. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkataraman K, Kannan AT, Mohan V. Challenges in diabetes management with particular reference to India. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2009;29:103–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.54286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramasamy K, Raman R, Tandon M. Current state of care for diabetic retinopathy in India. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:460–8. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao KD, Bhatnagar A, Murphy A. Socio-economic inequalities in the financing of cardiovascular & diabetes inpatient treatment in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:57–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartnett ME, Key IJ, Loyacano NM, Horswell RL, Desalvo KB. Perceived barriers to diabetic eye care: Qualitative study of patients and physicians. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:387–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Vijay V, King H. Impact of poverty on the prevalence of diabetes and its complications in urban southern India. Diabet Med. 2002;19:130–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis N, Forges B, Wylie-Rosett J. Role of obesity and lifestyle interventions in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. Minerva Med. 2009;100:221–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong X, Tanasugarn C, Fisher EB, Krudsood S, Nityasuddhi D. Awareness and practices of self-management and influence factors among individuals with type 2 diabetes in urban community settings in Anhui Province, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011;42:187–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding SP, Broadbent DM, Neoh C, White MC, Vora J. Sensitivity and specificity of photography and direct ophthalmoscopy in screening for sight threatening eye disease: The Liverpool Diabetic Eye Study. BMJ. 1995;311:1131–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7013.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens DR, Gibbins RL, Lewis PA, Wall S, Allen JC, Morton R. Screening for diabetic retinopathy by general practitioners: Ophthalmoscopy or retinal photography as 35 mm colour transparencies? Diabet Med. 1998;15:170–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199802)15:2<170::AID-DIA518>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raman R, Bhojwani DN, Sharma T. How accurate is the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy on telescreening. The Indian scenario? Rural Remote Health. 2014;14:2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]