Abstract

Purpose of the Study

To describe the clinicopathological features, mutational and chromosomal copy number analysis, and 8-year follow-up of a case of bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP) associated with clear-cell carcinoma of the endometrium.

Methods

Histological evaluation, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis and GNAQ/11 mutational analysis were performed in a 67-year-old female patient with the diagnosis of BDUMP.

Results

Histological evaluation revealed proliferation of bland spindle cells, diffusely replacing the uveal tract, which showed a proliferation index of less than 1%. There was absence of mutations involving the codon 209 and 183 of GNAQ, and of GNA11. MLPA analysis showed disomy 3 with polysomy 8q for both eyes. The patient died 8 years later of an unrelated condition.

Conclusions

Although BDUMP is considered to be a benign proliferative disease, copy number alterations of unknown significance may occur in these lesions.

Key Words: Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic hyperplasia, Endometrial carcinoma, Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, Paraneoplastic syndrome, GNAQ mutation

Introduction

Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP) is a rare and well-recognized ocular paraneoplastic syndrome with an enigmatic pathogenesis [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. It is most commonly associated with carcinomas of the ovary and lungs, followed in frequency by the gastrointestinal and genitourinary malignancies. It is characterized microscopically by an extensive proliferation of benign-appearing melanocytes, which have a very low proliferation index and which diffusely replace the uveal tract, causing overlying retinal and retinal pigment epithelial changes. There are few reports on genetic alterations in proliferating melanocytes of BDUMP [8,9,10]. We present a case of BDUMP, which we analyzed for chromosomal alterations using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), and for GNAQ and GNA 11 mutational status.

Caes Description

A 67-year-old woman was referred to the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre (LOOC) in July 2004 with a 1-month history of blurred vision in both eyes. On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity was counting fingers in both eyes. Cells and flare were present in the anterior chambers, associated with posterior synechiae and bilateral lens opacities (fig. 1). The intraocular pressures were normal. Poor pupillary dilatation and media opacities limited the ophthalmoscopic examination. B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated bilateral diffuse choroidal thickening and 360° ciliary body tumours (fig. 1). The clinical features were consistent with BDUMP. Transscleral choroidal biopsy of the right eye revealed a proliferation of benign melanocytic cells that stained positively with melan-A, confirming the diagnosis (fig. 1). Phacoemulsification of the left eye improved visual acuity to 20/125 and allowed a better view of the fundus, which showed multiple, slightly elevated, pigmented choroidal tumours (fig. 2). Systemic examination revealed a uterine mass with associated bilateral abdominal lymphadenopathy on magnetic resonance imaging.

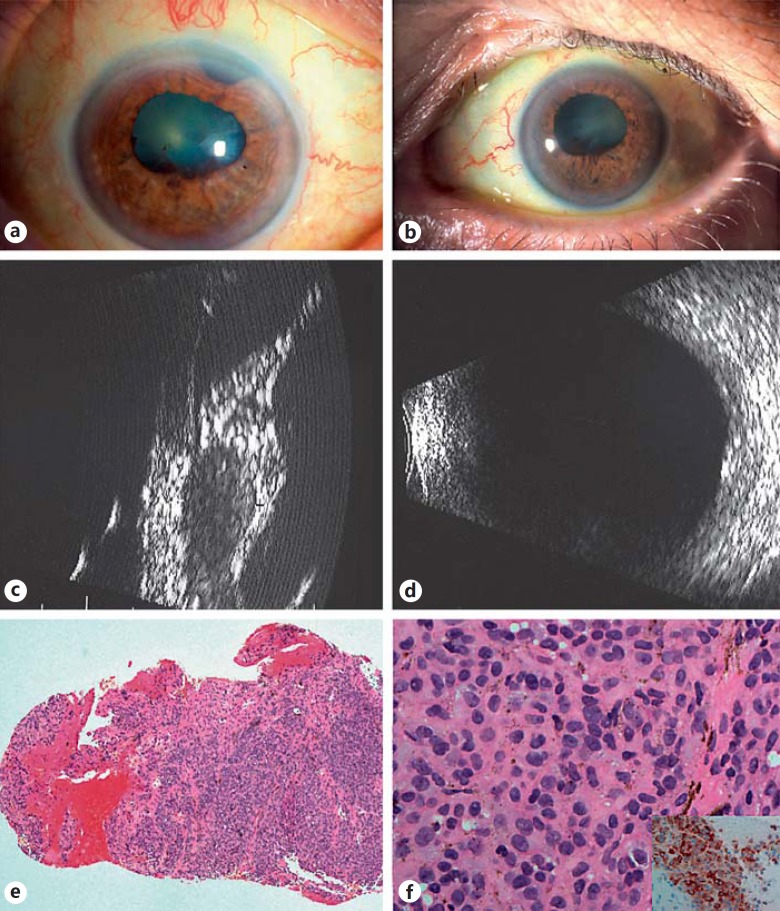

Fig. 1.

Ophthalmic examination of both eyes in 2004 revealed arcus senilus and fixed irregular pupillae, not permitting fundoscopy (a, b). Ultrasonography showed diffuse thickening in both eyes, anteriorly and posteriorly (c, d). A transscleral biopsy of the right eye was undertaken, showing choroidal tissue densely infiltrated by small naevoid-like cells with minimal atypia and staining for melan-A (e, f, inset). These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of BDUMP.

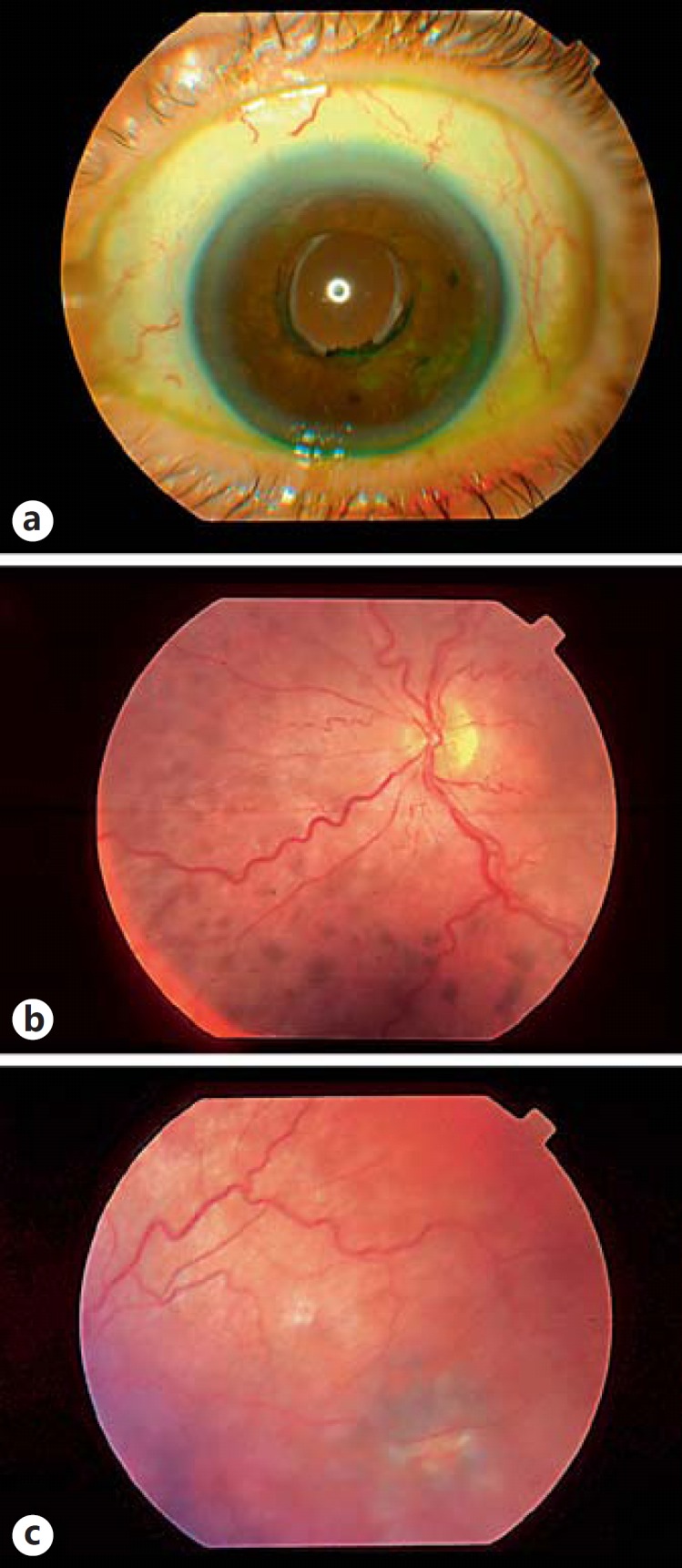

Fig. 2.

Ophthalmic examination of left eye in 2004 following phacoemulsification, allowing for fundoscopy showing diffuse mottled pigmentation of the choroid (a-c).

A month later, the patient complained of bilateral progressive visual loss. On examination, visual acuity was no-light perception in both eyes. Rubeosis iridis with a dense cataract and an intraocular pressure of 25 mm Hg was detected in the right eye. Electrophysiological studies were performed, and the electroretinogram (ERG) was almost absent with only a cortical response to the flash in this eye. The left eye showed reduction and delay of the ERG with rods more affected than cones, with a near normal pattern ERG, flash VEP and a pattern reversal VEP.

Cervical and endometrial biopsies, performed in August 2004, showed a poorly-differentiated clear-cell carcinoma of the endometrium. The patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy plus pelvic lymph node dissection, which revealed a metastasis in one of the pelvic nodes. She was subsequently treated with adjuvant carboplatin and external beam radiotherapy resulting in clinical remission.

Over the next 3 years, the patient was regularly reviewed by the LOOC team. There was no improvement in vision. Subsequently, in 2007 and 2008, the patient underwent enucleation of the right and then the left eye, as both the eyes were blind and painful. Histopathological examination of both eyes showed almost similar morphological features (fig. 3). There was diffuse thickening of the entire uveal tract and replacement by proliferation of variably pigmented melanocytic cells. These comprised a mixture of naevoid and spindle-shaped cells with elongated, oval to round nuclei, few nuclei displaying intranuclear inclusions and inconspicuous nucleoli. There were occasional cells displaying cellular atypia; however, there were no mitotic figures (fig. 3). These cells stained positively with melan-A and HMB45. Ki-67 stain showed a proliferation index of less than 1% (fig. 3).

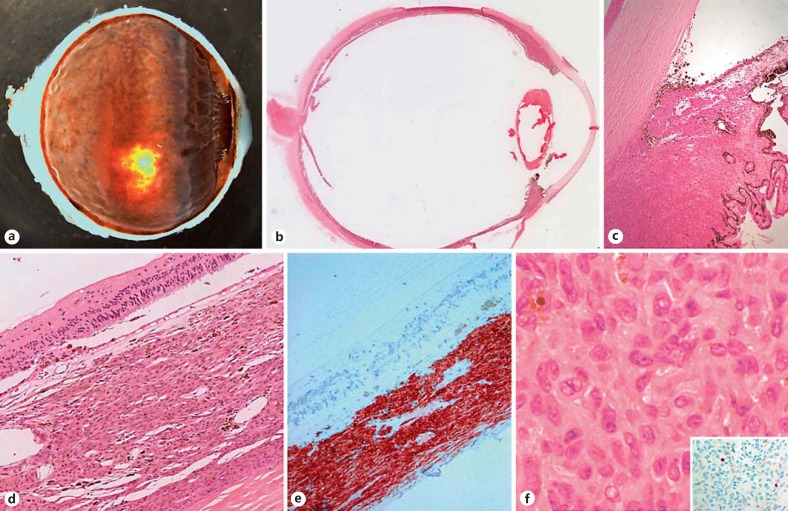

Fig. 3.

Enucleation specimen, right eye: diffuse thickening of the choroid, ciliary body and iris was observed on both the macroscopic and microscopic views (a, b). Higher power revealed infiltration of the BDUMP cells into the angle and along the posterior surface of the cornea (c). Histological examination of the choroid revealed its thickening by spindle cells positive for melan-A without any disruption of the overlying atrophic retina (d, e). The cells have a naevoid-like appearance with occasional nucleoli, and demonstrated a very low Ki-67 growth fraction (f, inset).

MLPA procedure and sequencing were performed as previously reported [11] using the SALSA P027.C1 Uveal Melanoma Kit, which examines copy number changes on chromosomes 1p, 3, 6 and 8. MLPA analysis showed that the majority of the dosage quotients for chromosomes 1p, 3 and 6 and 8p obtained from the 38 tested loci were within the normal range (0.85-1.15) in both eyes (fig. 4); however, there was amplification of probes on chromosome 8q. PCR for direct sequence analysis [12] of exons 4 and 5 of GNAQ/11 were performed using a Sanger sequencer on an ABI Prism 3730 xl DNA analyzer (Life Technologies, Foster City, Calif., USA) and was found to be negative for these mutations. Postoperatively, the patient was lost to follow-up from the eye clinic, but through tracing of the clinical notes it could be established that she died of an unrelated condition in 2012.

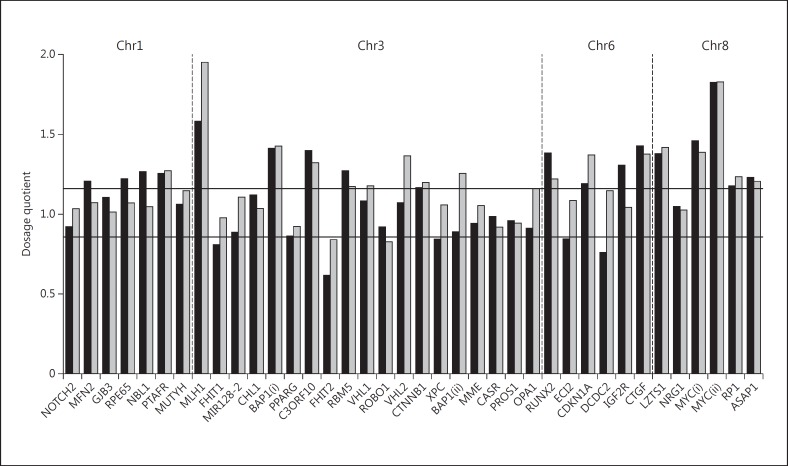

Fig. 4.

MLPA of the right and left eyes: the bar graph shows the copy number variations for chromosomes 1p, 3, 6 and 8 using MLPA. The two horizontal lines define the dosage quotient range for normal diploid copy number. Values above this range indicate gene amplifications, values below, deletions. The black bars represent the changes in the right eye, the grey bars, those in the left. Interestingly, amplifications on 8q in the region of c-myc were observed in both eyes.

Discussion

We present an unusual and rare case of BDUMP in a female patient diagnosed with a clear-cell carcinoma of the endometrium, with a detailed analysis of the clinical, histological, and genetic features of both enucleated eyes. The exact pathogenesis of BDUMP is unknown due to the rarity of the disease, and indeed there is no clear consensus as to whether it represents a neoplastic or a hyperplastic process. Three main mechanisms have been proposed for its development: (a) synchronous melanocytic proliferation and primary extraocular tumour development, caused by an unknown carcinogenic factor(s); (b) melanocytic proliferation secondary to an unknown factor or hormone secreted by the tumour, or (c) coincidental development of BDUMP and visceral malignancy, as a result of an unknown underlying genetic predisposition [3]. Many authors speculate that a humoral factor produced by the primary extraocular tumour induces the uveal melanocytes to proliferate [1,2]. This hypothesis is supported to some extent by in vitro data, e.g. the proliferation of cultured melanocytes was enhanced when treated with the IgG fraction of human serum from patients with BDUMP [13]. Furthermore, Sen et al. [6] reported total regression of BDUMP after excision of the underlying lung carcinoma. In our case, the persistent presence of BDUMP, even 4 years after apparent cure of the cancer, would seem to contradict the hypothesis that BDUMP is a hyperplastic response to an antibody or a secreted factor. It is possible, however, that microsatellites of clinically nondetectable endometrial cancer cells may have persisted in our patient.

Although there are over 50 cases of BDUMP reported in literature, only 3 of these have been evaluated for genetic alterations, with 2 of the 3 cases showing genetic abnormalities [8,10]. Mudhar et al. [8] described gains in chromosome 6 and X, and deletions in chromosome 19 in the BDUMP case they analysed. They also looked for mutations in GNAQ, GNA11 and BRAFV600E in the BDUMP melanocytes, but did not demonstrate these. Rahimy et al. [10] showed chromosome 5 gain in their case, and interestingly also described focal cytological atypia within the cells. The lack of GNAQ/GNA11 mutations in these 2 cases and in ours would suggest that if BDUMP represents a neoplastic process, it is one that possibly follows a different oncogenic pathway to uveal naevi and the majority of uveal melanomas [12]. In the present case, the authors observed polysomy 8q in BDUMP melanocytes within both eyes; however, there was minimal cytological atypia, a low Ki-67 proliferation index and no mitotic activity. The significance of this finding is uncertain, as is the aneuploidy found in 2 previously published cases of BDUMP. While there is a strong association between chromosomal abnormalities and neoplasia, aneuploidy is also seen in benign processes, including those involved in development and ageing (reviewed in [14] and [15]). Thus far, the analyses of BDUMP suggest it does not share the molecular hallmarks of uveal naevi or uveal melanoma. That a consistent chromosomal abnormality has not been identified by different authors lends more support to BDUMP being a hyperplastic rather than neoplastic process, differences in methodologies notwithstanding. However, cases with molecular analyses are still limited, and additional data is necessary before this question can be adequately answered.

Patients diagnosed with BDUMP tend to have poor survival, mainly because of the underlying systemic malignancy. The median survival of most BDUMP patients is 15.6 months [4]; however, there are reports of BDUMP patients surviving as long as 4 years and about 8.6 years, without and with enucleation [5,7]. These patients may even have multiple systemic malignancies and may present after several months to years with the systemic malignancy, so that prolonged systemic surveillance is mandatory [10]. Twenty-five percent of the BDUMP cases may have associated oral/mucosal and/or cutaneous involvement [9], so that extensive systemic and dermatological examination is mandatory in all cases with BDUMP. Further, what is most unusual about BDUMP is the rapid and profound visual loss, in our case progressing to bilateral no-light perception – out of keeping with glaucoma, cataract and any other apparent abnormality. The cause of this blindness is not yet known, but may be related to cancer-associated antibodies.

In summary, we present a patient with an 8-year survival following the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma and associated BDUMP, which persisted despite apparent clinical remission of the underlying systemic malignancy, and which demonstrated polysomy 8q on genetic analysis in the absence of cytological atypia, and GNAQ/GNA11 mutations. This case reveals more questions than answers: more detailed genetic studies are needed to unravel the mystery of this enigmatic disorder, and these in turn may provide additional information to our understanding of the pathogenesis of uveal melanocytic neoplasms.

Statement of Ethics

The patient had given full consent for the use of clinical data and images for educational and research purposes, and this report was written in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any financial disclosures to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank both Mr. Gary Cheetham and Ms. Nicola Longring for their help in obtaining all of the case note material and follow-up data.

References

- 1.Barr CC, Zimmerman LE, Curtin VT, Font RL. Bilateral diffuse melanocytic uveal tumors associated with systemic malignant neoplasms. A recently recognized syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:249–255. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030251003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filipic M, Ambler JS. Bilateral diffuse melanocytic uveal tumours associated with systemic malignant neoplasm. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol. 1986;14:293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1986.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gass JD, Gieser RG, Wilkinson CP, Beahm DE, Pautler SE. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation in patients with occult carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070060075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Neal KD, Butnor KJ, Perkinson KR, Proia AD. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation associated with pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and literature review of this paraneoplastic syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:613–625. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duong HV, McLean IW, Beahm DE. Bilateral diffuse melanocytic proliferation associated with ovarian carcinoma and metastatic malignant amelanotic melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:693–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen J, Clewes AR, Quah SA, Hiscott PS, Bucknall RC, Damato BE. Presymptomatic diagnosis of bronchogenic carcinoma associated with bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:156–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Salvo G, Prakash P, Rennie CA, Lotery AJ. Long-term survival in a case of bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:1385–1386. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mudhar HS, Scott I, Ul-Hassan A, Burton D, Doherty R, Cross N, Rennie IG, Sisley K. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic hyperplasia: molecular characterization and novel association with bilateral renal papillary carcinoma. Histopathology. 2012;61:751–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulido JS, Flotte TJ, Raja H, Miles S, Winters JL, Niles R, Jaben EA, Markovic SN, Davies J, Kalli KR, Vile RG, Garcia JJ, Salomao DR. Dermal and conjunctival melanocytic proliferations in diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation. Eye (Lond) 2013;27:1058–1062. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahimy E, Coffee RE, McCannel TA. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation as a precursor to multiple systemic malignancies. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30:206–209. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.835835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damato BE, Dopierala J, Klaasen A, van Dijk M, Sibbring J, Coupland S. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification of uveal melanoma: correlation with metastatic death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3048–3055. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, Garrido MC, Vemula S, Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Wackernagel W, Green G, Bouvier N, Sozen MM, Baimukanova G, Roy R, Heguy A, Dolgalev I, Khanin R, Busam K, Speicher MR, O'Brien J, Bastian BC. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miles SL, Niles RM, Pittock S, Vile R, Davies J, Winters JL, Abu-Yaghi NE, Grothey A, Siddiqui M, Kaur J, Hartmann L, Kalli KR, Pease L, Kravitz D, Markovic S, Pulido JS. A factor found in the IgG fraction of serum of patients with paraneoplastic bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation causes proliferation of cultured human melanocytes. Retina. 2012;32:1959–1966. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182618bab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Iourov IY. Ontogenetic variation of the human genome. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:420–425. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricke RM, van Deursen JM. Aneuploidy in health, disease, and aging. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:11–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]