Abstract

Purpose of the Study

To describe the rare occurrence of a paraganglioma in the orbit and how to triage for genetic testing and assess the prognosis with succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) immunohistochemical staining.

Method

Case report.

Procedures

A 47-year-old ‘healthy’ male presented with painless exophthalmos and diplopia secondary to an infraorbital tumour mass.

Results

The orbital biopsy was diagnosed as paraganglioma with positive staining with SDHB.

Conclusion

The rarity of an orbital paraganglioma was followed by the clinical search for a possible occult extraorbital primary paraganglioma. SDHB staining helped in the triage for genetic testing and gave an idea about the prognosis for this tumour.

Key Words: Paraganglioma, Orbit, Succinate dehydrogenase immunohistochemical stain, Familial syndrome

Introduction

Paraganglia are groups of chromaffin cells of neural crest origin (neuroendocrine) distributed all over the body. They sense fluctuations in blood pH and oxygen tension and help in their homeostasis [1,2]. Paragangliomas are neuroendocrine tumours that arise from the paraganglia and are found frequently neighbouring vascular structures. In general terms, they can be divided into adrenal and extra-adrenal. They are often multifocal and are 10 times more common in persons living in high altitude [3].

The symptomatology depends on the location of the tumour: carotid (painless mass), jugulo-tympanic (dizziness, tinnitus or cranial nerve palsy), vagal (Horner syndrome and vocal cord paralysis), retroperitoneal (back pain and a mass) and adrenal (mass) [2,3]. However, the possibility that in the orbit it may be secondary rather than primary has to be considered. Paragangliomas are rarely seen in the orbit, with less than 40 cases reported in the literature [2,4,5]. The site of origin in the orbit is controversial since the presence of paraganglionic tissue in the orbit is not well established. Paragangliomas in the orbit are therefore alleged to originate from the sustentacular cells, whereas others believe they arise from the paraganglia of the ciliary nerve [2].

There is a definite familial incidence, with up to 35% of these tumours being hereditary [4]. Molecular and genetic studies have identified germline mutations of six genes that contribute to the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PCC/PGL) in patients. Three of them belong to the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) family (SDHx) [4].

Material and Methods

A 47-year-old previously healthy male presented with a painless right inferior, right orbital, non-pulsatile mass causing mild exophthalmos and diplopia. Visual acuity and ocular movements were preserved. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. No relevant previous medical or family history was noted. On imaging, the lesion was described as an enhancing mass inferior to the right globe, abutting the right orbital canal, measuring 13 × 13 mm and causing mild upward globe displacement (fig. 1a).

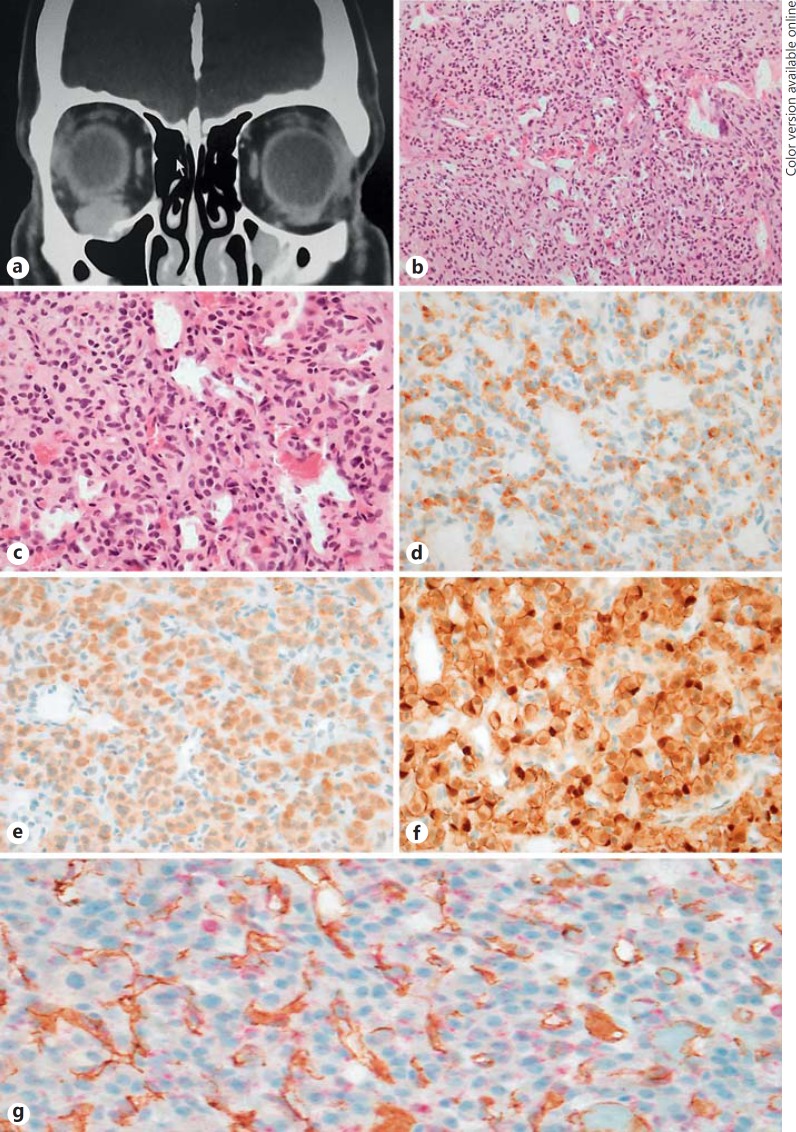

Fig. 1.

a-g Orbital paraganglioma. a CT scan with an enhancing mass inferior to the right globe measuring 13 × 13 mm, abutting the right canal and causing mild upward globe displacement. b Nests of polygonal cells on a vascularised stroma, consistent with paraganglioma. HE. ×200. c Nests of polygonal cells on a vascularised stroma, consistent with paraganglioma. HE. ×400. d Paraganglioma cells positive for chromogranin immunohistochemical stain. ×400. e Paraganglioma cells positive for synaptophysin immunohistochemical stain. ×400. f Sustentacular cells highlighted with S100 immunohistochemical stain. g SDH immunohistochemical stain (red) with granular cytoplasmic staining in paraganglioma tumour cells with a positive internal control in endothelial cells (CD31, brown), a pattern of staining consistent with a positive result. ×400.

A biopsy was performed with clinical notes indicating a profusely vascular tumour. Macroscopically, the lesion was composed of multiple fragments of haemorrhagic fleshy tumour. The histopathology analysis revealed nests of polygonal cells, both chromogranin and synaptophysin positive (fig 1d, e), with S100-positive sustentacular cells (fig. 1f), amongst a delicate vascular stroma. Zellballen were highlighted with reticulin stain. The tumour nuclei were oval, hyperchromatic and showed focal nuclear pleomorphism (fig. 1b, c). No mitoses or necrosis was noted. No intracytoplasmic crystals were seen on PAS staining. Other stains performed included cytokeratin A1/A3, CK7, CD10, Melan A, SMA and CD34; all of them were negative.

Double staining with SDHB stain (red) and CD31 (brown) showed granular cytoplasmic staining in tumour cells with a positive internal control in endothelial cells, a pattern of staining consistent with a positive result (fig. 1g). In consequence, SDH gene mutational analysis was not recommended in this case (SDH-negative staining, which is an indicator of complex II disruption caused by SDHx mutations).

Discussion

Paragangliomas are rarely seen in the head and neck region (less than 3%), and very rarely, this tumour may be seen within the orbit, with fewer than 40 cases reported in the literature [1,5]. Paragangliomas show a definite familial incidence, with up to 35% of these tumours being hereditary [4].

This tumour usually follows a benign clinical course (90%). It is slow growing and may remain stable for years [5,6]. There is an overall incidence of malignant transformation of about 10%, with no reliable histological criteria that predict malignancy. The only reliable criterion for malignancy is metastasis [5,7,8]. However, recent publications have suggested that a lack of SDHB staining in paraganglioma cells is a marker of adverse outcome in both sporadic and familial PCC/PGL [9]. The possibility of metastatic paraganglioma was contemplated in view that the lesion was not arising from the ciliary ganglion or ciliary nerve sustentacular tissue.

Molecular and genetic studies have identified germline mutations of six genes that contribute to the development of PCC/PGL in patients: RET (‘rearranged during transfection’ proto-oncogene, predisposing to multiple endocrine neoplasia), VHL (predisposing to von Hippel-Lindau syndrome), NF1 (associated with neurofibromatosis type 1) and SDH [10]. SDH subunit mutations (SDHB, SDHC and SDHD) predispose to PCC/PGL syndromes that otherwise may be regarded as sporadic in nature, because many of the patients do not display the expected clinical association with multifocal disease, young age and/or positive family history [4,10,11].

SDH is an enzyme complex that catalyzes the oxidation of succinate to fumarate in the citric acid cycle and participates in the electron transport chain. SDH is located in the mitochondrial inner membrane and consists of four nuclear-encoded subunits: the flavoprotein SDHA, the iron-sulfur protein SDHB and the integral membrane proteins SDHC and SDHD [4,11]. Burnichon et al. [11] supported previous findings of the high frequency of SDH mutations in head and neck paragangliomas, as well as a higher frequency of abdominal and pelvic disease and overall malignancy in SDH mutations. In PCC/PGL, the absence of SDH staining by immunohistochemistry is an indicator of complex II disruption caused by SDHB, SDHC or SDHD mutations [4] and has been reported as a marker to predict malignancy [9]. Mutations in the tumour suppressor gene SDH family, referred to collectively as SDHx, occur in patients with the PCC/PGL syndromes.

Following SDHB immunohistochemical evaluation, SDHx gene mutational analysis is performed on the tumours with negative SDHB immunohistochemistry [9]. Our case showed granular cytoplasmic staining in tumour cells with a positive internal control in endothelial cells with SDHB immunohistochemistry stain, a pattern of staining consistent with a positive result, hence not requiring genetic analysis. Systemic imaging including CT of the abdomen and chest X-ray showed no evidence of an extraorbital mass or renal/adrenal mass, eliminating the orbit as a possible secondary site.

Conclusion

In summary, a paraganglioma is of rare occurrence in the orbit and should alert clinicians for further investigation in search for a possible primary site outside the orbit. SDHB immunohistochemical staining can triage patients for genetic testing for paragangliomas, given its well-known familial predisposition in up to 35% of cases as well as its description as a marker to predict malignancy.

Statement of Ethics

Subjects were notified of the implications of special tissue staining testing (SDHB) to triage for genetic testing, in accordance to the Institute's Committee on Human Research.

Disclosure Statement

There is no financial disclosure and no conflict of interest to be reported.

References

- 1.Sharma MC, Epari S, Gaikwad S, Verma A, Sarkar C. Orbital paraganglioma: report of a rare case. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40:640–644. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill RH, 3rd, Platt SM, Bersani A, Barker-Griffith A, Strumpf K. Regression of a paraganglioma tumor of the orbit. Orbit. 2015;34:99–102. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2014.950290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedner MM, Trainer TD, Aitken PA, Grenko R, Dorwart R, Duckworth J, Gross CE, Pendlebury WW. Orbital paraganglioma: case report and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:183–185. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagheri A, Aletha M, Salour H, Abdollahi A, Silbert D, Rezaei-Kanavi M. Orbital paraganglioma presenting as lateral rectus enlargement and its novel management: a case report and review of the literature. Orbit. 2012;31:256–260. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2012.689078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makhdoomi R, Nayil K, Santosh V, Kumar S. Orbital paraganglioma: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropatol. 2010;29:100–104. doi: 10.5414/npp29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill AJ. Use of SDHB immunohistochemistry to identify germline mutations of SDH genes. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2012;10:A7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorbeck V, Morales V, Ruiz Morales M. Non-chromaffin paraganglioma of the orbit. Case report. Zentralbl Chir. 1986;111:46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raygada M, Pasini B, Stratakis CA. Hereditary paraganglioma. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;70:99–106. doi: 10.1159/000322484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank A, Schmitt A, Korpershoek E, van Nederveen F, Rudoplh T, Weber N, Strebel RT, de Krijger R, Komminoth P, Perrem A. SDHB loss predicts malignancy in pheochromocytoma/sympathethic paragangliomas, but not through hypoxia signalling. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:919–928. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaal J, Stratakis CA, Carney JA, Ball ER. SDHB immunohistochemistry: a useful tool in the diagnosis of Carney-Stratakis and Carney triad gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:147–151. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnichon N, Rohmer V, Hernan P, Leboulleux S, Darrouzet V, Niccolo P, Gaillard D, Chabrier G, Chabolle F, Coupier I, Thebilot P, Lecomte P, Bertherat J, Wion-Barbot N, Murat A, Venisse A, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. The succinate dehydrogenase genetic testing in large prospective series of patients with paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2817–2827. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]