Abstract

Background

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines at no cost to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN), or underinsured and vaccinated at Federally Qualified Health Centers or Rural Health Clinics. The objective of this study was to compare influenza vaccination coverage of VFC-entitled to privately insured children in the United States, nationally, by state, and by selected socio-demographic variables.

Methods

Data from the National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu) surveys were analyzed for the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons for households with children 6 months–17 years. VFC-entitlement and private insurance status were defined based upon questions asked of the parent during the telephone interview. Influenza vaccination coverage estimates of children VFC-entitled versus privately insured were compared by t-tests, both nationally and within state, and within selected socio-demographic variables.

Results

For both seasons studied, influenza coverage for VFC-entitled children did not significantly differ from coverage for privately insured children (2011–2012: 52.0% ± 1.9% versus 50.7% ± 1.2%; 2012–2013: 56.0% ± 1.6% versus 57.2% ± 1.2%). Among VFC-entitled children, uninsured children had lower coverage (2011–2012: 38.9% ± 4.7%; 2012–2013: 44.8% ± 3.5%) than Medicaid-eligible (2011–2012: 55.2% ± 2.1%; 2012–2013: 58.6% ± 1.9%) and AI/AN children (2011–2012: 54.4% ± 11.3%; 2012–2013: 54.6% ± 7.0%). Significant differences in vaccination coverage among VFC-entitled and privately insured children were observed within some subgroups of race/ethnicity, income, age, region, and living in a metropolitan statistical area principle city.

Conclusions

Although finding few differences in influenza vaccination coverage among VFC-entitled versus privately insured children was encouraging, nearly half of all children were not vaccinated for influenza and coverage was particularly low among uninsured children. Additional public health interventions are needed to ensure that more children are vaccinated such as a strong recommendation from health care providers, utilization of immunization information systems, provider reminders, standing orders, and community-based interventions such as educational activities and expanded access to vaccination services.

Keywords: Influenza, Vaccination coverage, VFC, Children, Private insurance, NIS-Flu

1. Introduction

Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among children 6 months–17 years has been increasing, from 43.7% in the 2009–2010 influenza season to 56.6% in the 2012–2013 season [1–4]. Despite these increases, influenza vaccination coverage among children is still below the Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) revised target of 70% [5,6]. The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program has reduced racial/ethnic disparities in childhood vaccination coverage, improved vaccination rates among children, and fostered discontinuance of referring children to health department clinics by allowing children to be vaccinated in their medical home [7–9]. The VFC program was created by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 and first implemented in 1994, and is a federal entitlement program that provides vaccines at no cost to children who might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay [10,11]. Children ≤18 years are entitled to receive VFC vaccines if they are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN), or underinsured and vaccinated at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) or Rural Health Clinics (RHC) [11]. Studies of the association between insurance status and vaccination coverage among children for recommended vaccines other than influenza have shown that children with health insurance have higher vaccination coverage than uninsured children [12–18].

Differences in influenza vaccination coverage between VFC-entitled and privately insured children 6 months–17 years have not been evaluated with a national sample, nor have such differences in coverage been evaluated among socio-demographic subgroups of children. Identifying and quantifying any differences in childhood influenza vaccination coverage by insurance status could help guide public health action to increase influenza vaccination coverage for all children. This study was undertaken to compare influenza vaccination coverage of VFC-entitled versus privately insured children 6 months–17 years in the United States, nationally and by state, and to assess for any difference within select socio-demographic subgroups.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey description

We analyzed data from the National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu) surveys for two influenza seasons: 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 [1–3]. The NIS-Flu survey is an ongoing, national list-assisted random-digit-dial survey of households with either landline telephone or cellular telephone numbers, and has a target population of non-institutionalized children 6 months–17 years [1]. The survey includes three components: the NIS-Child for children 19–35 months, the NIS-Teen for children 13–17 years, and a short child influenza module for children 6–18 months and 3–12 years [1,19,20]. The Council of American Survey and Research Organizations (CASRO) response rates for the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons ranged from 51.8% to 63.2% for the landline sample and 18.1% to 30.9% for the cellular telephone sample [21]. Data on child, maternal, and household socio-demographic characteristics were collected during the telephone interviews.

2.2. VFC-entitled and private insurance group definitions

Data from the NIS-Flu surveys were used to evaluate whether the children were (i) on Medicaid, (ii) not covered by health insurance (uninsured), (iii) AI/AN, or (iv) privately insured. These evaluations were based upon insurance questions asked of the parent during the telephone interview. While the NIS-Child and NIS-Teen components of the NIS-Flu had a long series of questions to determine insurance status of the child, there were only two insurance questions included on the influenza module for children 6–18 months and 3–12 years. The two questions were as follows: “Does [child] have any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as Health Maintenance Organizations, or government plans such as Medicaid?” and “Is that coverage Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, or some other type of insurance?” Precise VFC-entitlement status could not be determined because of the inability to identify the underinsured and vaccinated at FQHC/RHC group with the NIS-Flu survey questions. Thus, for this study, the VFC-entitled group consisted of children who were reported as uninsured, Medicaid-eligible, or AI/AN, categories which are not mutually exclusive. The privately insured group consisted of children reported as having private health insurance.

2.3. Influenza vaccination coverage assessment

Influenza vaccination status was assessed by asking the parent if the survey-selected child(ren) in the household had received an influenza vaccination since July 1 and, if so, in which month and year. The parental responses about whether a child had received influenza vaccine were not validated with medical records. For the 2011–2012 season, interview data collected during September 2011 through June 2012 were included in the analyses, and children reported to have received influenza vaccination July 2011 through May 2012 were considered vaccinated. For the 2012–2013 season, interview data collected during October 2012 through June 2013 were included in the analyses, and children reported to have received influenza vaccination July 2012 through May 2013 were considered vaccinated. For children who were reported to have been vaccinated but had a missing month and year of vaccination (6.1% for the 2011–2012 season and 6.0% for the 2012–2013 season), month and year of vaccination was imputed from donor pools matched for week of interview, age group, state of residence, and race/ethnicity [2,3]. Estimation of influenza vaccination coverage was based on the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis procedure that has been used to calculate season-specific estimates starting with the 2009–2010 influenza season [1,3,22,23]. Influenza vaccination coverage estimates were calculated by private health insurance and VFC-entitlement status at the national level. Influenza vaccination coverage by private health insurance and VFC-entitlement status was also calculated by state and within select socio-demographic sub-groups.

2.4. Statistical methods

Comparisons of influenza vaccination coverage estimates between VFC-entitled and privately insured children and between the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 seasons were performed with t-tests assuming large degrees of freedom. All analyses were weighted to the United States population of non-institutionalized children 6 months–17 years. The weights used to calculate the routine parental-reported influenza vaccination coverage estimates for children that are published on CDC’s FluVaxView website could not be used for this study [24] because, for the NIS-Child and NIS-Teen components of the NIS-Flu, the insurance questions are asked only after the parent grants permission to contact the child’s vaccination provider to obtain vaccination records; insurance status is therefore missing for children whose parents did not grant permission for the NIS to contact their providers. Thus, a new set of weights was derived so that the sample of children with insurance information is representative of the population of non-institutionalized children 6 months–17 years in the United States. To quantify the possible extent of differences due to the reweighting, we compared the reweighted estimates for the subset of data analyzed for this study to the published final estimates that used all the data for both seasons studied. We found that for the 2011–2012 season, the differences between this study estimates and the published final estimates ranged from −1.6% to 0.5%. Similarly, for the 2012–2013 season, the differences ranged from −0.2% to 1.3%.

The analyses for this study included 83,411 children for the 2011–2012 season and 87,661 children for the 2012–2013 season. All estimates, along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated using SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, version 9.3) and SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, version 10.01) to account for the complex survey design. All tests were two-sided and all comparisons noted as differences were statistically significant at alpha equal to 0.05 while comparisons noted as similar or the same were not statistically different at the p < 0.05 level.

2.5. Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for conducting the NIS-Flu was obtained through the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board and through the IRB of NORC at the University of Chicago.

3. Results

Nationally, 34.2% of children 6 months–17 years old were VFC-entitled during the 2011–2012 season based on the proxy variable that excluded underinsured and vaccinated at FQHC/RHC children, and 65.8% had private insurance (Table 1). In this season, 26.4% were enrolled in Medicaid, 6.6% were uninsured, and 2.2% were AI/AN. In the 2012–2013 season, 37.0% of children were considered VFC-entitled with 28.6% enrolled in Medicaid, 6.8% uninsured, and 3.1% AI/AN; 63.0% of children were privately insured. The distribution of socio-demographic characteristics of the sample surveyed is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic distribution and influenza vaccination coverage estimates, children 6 months–17 years, National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu), 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons.

| Socio-demographic characteristics | 2011–2012 influenza season

|

2012–2013 influenza season

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % ± 95% CIa | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | n | % ± 95% CI | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | ||

| VFCb/Insurance status | VFC-entitled | 25,382 | 34.2 ± 0.9 | 52.0 ± 1.9 | 29,015 | 37.0 ± 0.8c | 56.0 ± 1.6c |

| Uninsured | 4675 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 38.9 ± 4.7 | 5707 | 6.8 ± 0.4 | 44.8 ± 3.5c | |

| Medicaid | 19,146 | 26.4 ± 0.8 | 55.2 ± 2.1 | 21,608 | 28.6 ± 0.7c | 58.6 ± 1.9c | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3021 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 55.0 ± 7.0 | 3493 | 3.1 ± 0.3c | 55.5 ± 5.2 | |

| Privately insured | 58,029 | 65.8 ± 0.9 | 50.7 ± 1.2 | 58,646 | 63.0 ± 0.8c | 57.2 ± 1.2c | |

| Age | 6–23 months | 9013 | 10.4 ± 0.5 | 74.2 ± 3.0 | 10,288 | 9.6 ± 0.4c | 78.2 ± 2.6c |

| 2–4 years | 14,286 | 16.2 ± 0.6 | 63.8 ± 2.3 | 15,491 | 15.6 ± 0.5 | 65.6 ± 2.0 | |

| 5–12 years | 40,690 | 44.6 ± 0.8 | 54.4 ± 1.4 | 47,391 | 45.2 ± 0.7 | 58.5 ± 1.3c | |

| 13–17 years | 19,422 | 28.8 ± 0.8 | 32.1 ± 2.0 | 14,491 | 29.6 ± 0.7 | 43.3 ± 1.9c | |

| Gender | Male | 42,964 | 51.2 ± 0.9 | 51.6 ± 1.4 | 45,423 | 51.2 ± 0.7 | 56.4 ± 1.3c |

| Female | 40,447 | 48.8 ± 0.9 | 50.6 ± 1.5 | 42,238 | 48.8 ± 0.7 | 57.2 ± 1.4c | |

| Race/ethnicity | Non-Hispanic, white only | 52,384 | 57.1 ± 0.9 | 47.2 ± 1.2 | 53,432 | 53.4 ± 0.8c | 54.1 ± 1.1c |

| Non-Hispanic, black only | 8838 | 14.9 ± 0.7 | 53.1 ± 3.1 | 8820 | 14.0 ± 0.6 | 57.3 ± 3.0 | |

| Hispanic | 13,600 | 22.2 ± 0.8 | 59.3 ± 2.8 | 15,448 | 23.4 ± 0.8c | 60.8 ± 2.5 | |

| Non-Hispanic other/multiple races | 8589 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 53.2 ± 3.2 | 9961 | 9.2 ± 0.4c | 61.4 ± 3.0c | |

| Metropolitan statistical area (MSA) | MSA, principle city | 26,841 | 32.6 ± 0.9 | 55.1 ± 2.0 | 29,451 | 32.9 ± 0.8 | 59.6 ± 1.7c |

| MSA, not principle city | 38,017 | 51.8 ± 0.9 | 50.3 ± 1.5 | 38,147 | 49.9 ± 0.8c | 56.5 ± 1.5c | |

| Non-MSA | 18,553 | 15.7 ± 0.5 | 45.4 ± 2.0 | 20,063 | 17.2 ± 0.5c | 52.2 ± 1.8c | |

| Annual income/poverty leveld | Above poverty, ≥$75,000 | 32,791 | 34.9 ± 0.8 | 50.7 ± 1.5 | 33,336 | 33.5 ± 0.7c | 59.6 ± 1.5c |

| Above poverty, <$75,000 | 31,311 | 36.0 ± 0.9 | 46.8 ± 1.7 | 32,067 | 35.1 ± 0.8 | 52.3 ± 1.6c | |

| At or below poverty level | 13,709 | 22.5 ± 0.8 | 57.2 ± 2.7 | 15,444 | 24.1 ± 0.8c | 59.6 ± 2.2 | |

| Unknown | 5600 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 56.0 ± 3.6 | 6814 | 7.3 ± 0.4c | 56.9 ± 3.3 | |

| Regione | Northeast | 15,364 | 16.7 ± 0.5 | 58.3 ± 2.0 | 17,311 | 16.4 ± 0.4 | 66.1 ± 1.9c |

| Midwest | 17,083 | 21.5 ± 0.5 | 47.5 ± 1.7 | 18,083 | 21.6 ± 0.5 | 54.0 ± 1.6c | |

| South | 32,305 | 37.6 ± 0.8 | 50.8 ± 1.7 | 31,773 | 37.8 ± 0.7 | 55.5 ± 1.6c | |

| West | 18,659 | 24.2 ± 0.8 | 49.8 ± 2.8 | 20,494 | 24.2 ± 0.7 | 54.7 ± 2.5c | |

n is unweighted sample size.

Confidence interval.

Vaccines for Children program. The VFC-entitled group consisted of children who were either uninsured, Medicaid eligible, or an American Indian or Alaska Native. Children may fall into more than one of these categories; therefore, the numbers and proportions of children in each of the VFC-entitled subgroups sum to more than the overall number and proportion of VFC-entitled children in the sample.

Statistically significant difference compared to the 2011–2012 influenza season estimates.

Poverty level was defined based on the reported number of people living in the household and annual household income, and the U.S. Census poverty thresholds.

Classification was based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s census region definition.

Influenza vaccination coverage was higher in the 2012–2013 season compared to the 2011–2012 season for both VFC-entitled (56.0% versus 52.0%) and privately insured children (57.2% versus 50.7%; Table 1). This increase occurred in all subgroups of VFC-entitlement studied except the AI/AN children in which coverage remained similar. Influenza vaccination coverage by the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample is included in Table 1.

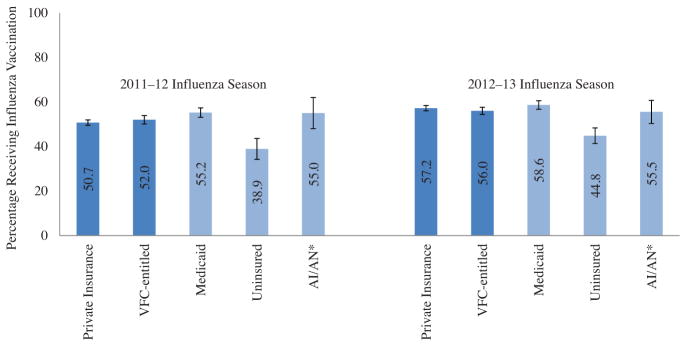

Nationally, VFC-entitled children had similar influenza vaccination coverage compared to privately insured children in both influenza seasons studied, with coverage being 52.0% versus 50.7%, respectively, in the 2011–2012 season and 56.0% versus 57.2%, respectively, in the 2012–2013 season (Fig. 1). Within the VFC-entitled group of children, uninsured children had lower influenza vaccination coverage than Medicaid insured children in both seasons studied, with coverage being 38.9% versus 55.2%, respectively, in the 2011–2012 season and 44.8% versus 58.6%, respectively, in the 2012–2013 season (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Influenza vaccination coverage among children 6 months–17 years by insurance status and Vaccines for Children (VFC) entitlement status, National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu), 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons. * AI/AN: Alaska Indian/Alaska Native. The VFC-entitled group does not include underinsured children. Uninsured children had lower influenza vaccination coverage than Medicaid insured children in both seasons (both p < 0.05); the uninsured children had lower coverage compared to the AI/AN group in both seasons (both p < 0.05), and the coverage of Medicaid insured children did not differ from coverage of AI/AN children.

By state, influenza vaccination coverage varied widely among VFC-entitled and privately insured children during both seasons (Table 2). During the 2011–2012 season, coverage among VFC-entitled children ranged from 34.2% in Arizona to 74.9% in Rhode Island, and coverage among privately insured children ranged from 34.7% in Alaska to 73.9% in Rhode Island. During the 2012–2013 season, coverage among VFC-entitled children ranged from 40.3% in Missouri to 87.1% in Rhode Island, and coverage among privately insured children ranged from 41.6% in Montana to 81.4% in Rhode Island. Coverage among VFC-entitled children exceeded 70% in three states and among privately insured children in one state during the 2011–2012 season. Coverage among VFC-entitled children exceeded 70% in eight states and among privately insured children in four states during the 2012–2013 season. In only nine states were there differences in coverage between VFC-entitled and privately insured children during the 2011–2012 season, and in two states during the 2012–2013 season. During the 2011–2012 season, three states had lower coverage among VFC-entitled children and six states had lower coverage among privately insured children. During the 2012–2013 season, one state had lower coverage among VFC-entitled children and one state had lower coverage among privately insured children. Comparing influenza vaccination coverage between seasons, VFC-entitled children had higher coverage in seven states and privately insured children had higher coverage in 16 states in the 2012–2013 season than in the 2011–2012 season.

Table 2.

Influenza vaccination coverage by Vaccines for Children (VFC) entitlement status and by state, children 6 months–17 years, National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu), 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons.

| State | 2011–2012 influenza season

|

2012–2013 influenza season

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFC-entitled

|

Privately insured

|

VFC-entitled

|

Privately insured

|

|||||

| n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CIa | n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | |

| Overall | 25,382 | 52.0 ± 1.9 | 58,029 | 50.7 ± 1.2 | 29,015 | 56.0 ± 1.6b | 58,646 | 57.2 ± 1.2b |

| Alabama | 513 | 50.3 ± 9.9 | 1009 | 47.7 ± 6.1 | 495 | 56.0 ± 9.6 | 849 | 50.1 ± 7.4 |

| Alaska | 607 | 42.6 ± 8.4 | 738 | 34.7 ± 6.4 | 749 | 48.3 ± 7.0 | 849 | 45.5 ± 6.5b |

| Arizona | 384 | 34.2 ± 10.3c | 1105 | 52.8 ± 7.8d | 458 | 48.9 ± 8.1b | 1217 | 48.5 ± 5.2 |

| Arkansas | 350 | 54.4 ± 12.7c | 1219 | 65.4 ± 6.0 | 434 | 60.1 ± 9.5 | 1039 | 64.5 ± 6.3 |

| California | 335 | 48.7 ± 10.8c | 1236 | 52.7 ± 5.4 | 429 | 53.8 ± 8.0 | 1414 | 56.7 ± 5.5 |

| Colorado | 393 | 46.9 ± 9.8 | 1222 | 52.1 ± 5.9 | 463 | 62.7 ± 7.6b | 1238 | 58.1 ± 4.9 |

| Connecticut | 417 | 66.5 ± 9.3 | 1138 | 59.5 ± 5.9 | 503 | 67.6 ± 7.9 | 1189 | 65.8 ± 5.4 |

| Delaware | 357 | 61.5 ± 11.2c | 1061 | 52.6 ± 8.4 | 550 | 73.3 ± 7.1 | 1086 | 62.0 ± 9.8 |

| D.C. | 504 | 55.6 ± 9.9 | 842 | 68.3 ± 9.4 | 530 | 77.5 ± 9.3b | 893 | 70.2 ± 9.4 |

| Florida | 509 | 50.1 ± 9.0 | 839 | 43.6 ± 11.0c | 640 | 51.0 ± 10.3c | 813 | 45.2 ± 6.6 |

| Georgia | 374 | 45.9 ± 12.3c | 1130 | 42.0 ± 5.5 | 386 | 45.8 ± 9.5 | 978 | 53.1 ± 5.8b |

| Hawaii | 490 | 71.4 ± 20.8c | 994 | 68.6 ± 6.5 | 547 | 71.6 ± 14.2c | 1054 | 72.7 ± 7.5 |

| Idaho | 434 | 41.9 ± 8.7 | 870 | 42.4 ± 6.7 | 500 | 47.3 ± 8.7 | 834 | 41.9 ± 5.9 |

| Illinois | 1164 | 49.4 ± 7.1 | 1702 | 39.8 ± 4.8d | 1287 | 54.6 ± 6.3 | 1684 | 51.4 ± 5.3b |

| Indiana | 573 | 50.7 ± 8.2 | 971 | 43.3 ± 5.5 | 556 | 55.8 ± 7.2 | 831 | 52.8 ± 5.8b |

| Iowa | 345 | 55.8 ± 9.5 | 1052 | 48.9 ± 4.9 | 357 | 51.0 ± 9.0 | 973 | 57.7 ± 5.3b |

| Kansas | 418 | 40.8 ± 9.5 | 1061 | 49.0 ± 5.4 | 477 | 44.7 ± 7.6 | 834 | 46.3 ± 5.2 |

| Kentucky | 382 | 38.2 ± 9.4 | 967 | 54.6 ± 6.0d | 419 | 55.7 ± 10.3b,c | 984 | 58.2 ± 6.1 |

| Louisiana | 735 | 57.0 ± 8.4 | 907 | 48.4 ± 6.1 | 869 | 55.4 ± 7.5 | 912 | 57.6 ± 6.3b |

| Maine | 537 | 61.2 ± 7.4 | 797 | 59.6 ± 6.2 | 568 | 60.0 ± 7.8 | 824 | 61.9 ± 6.6 |

| Maryland | 385 | 74.1 ± 18.3c | 1781 | 61.0 ± 8.3 | 277 | 63.8 ± 14.6c | 1379 | 66.5 ± 7.3 |

| Massachusetts | 150 | 62.2 ± 15.7c | 1132 | 62.7 ± 5.3 | 218 | 79.5 ± 7.4 | 1334 | 76.0 ± 4.4b |

| Michigan | 400 | 37.1 ± 9.2 | 1129 | 47.9 ± 5.0d | 421 | 49.5 ± 8.0b | 1078 | 53.1 ± 5.8 |

| Minnesota | 272 | 58.8 ± 10.8c | 918 | 46.7 ± 6.0 | 317 | 61.0 ± 10.7c | 955 | 63.4 ± 5.7b |

| Mississippi | 569 | 38.5 ± 8.7 | 831 | 48.3 ± 7.3 | 611 | 48.1 ± 8.4 | 819 | 49.6 ± 6.8 |

| Missouri | 414 | 45.1 ± 10.2c | 882 | 44.8 ± 6.3 | 475 | 40.3 ± 9.5 | 917 | 54.2 ± 5.4b,d |

| Montana | 456 | 42.6 ± 9.7 | 1134 | 43.1 ± 5.4 | 472 | 46.5 ± 8.8 | 1185 | 41.6 ± 5.6 |

| Nebraska | 314 | 57.8 ± 11.0c | 741 | 49.1 ± 6.9 | 401 | 57.7 ± 9.0 | 881 | 57.7 ± 6.4 |

| Nevada | 501 | 45.1 ± 10.9c | 1001 | 45.8 ± 8.3 | 607 | 56.0 ± 8.3 | 1134 | 51.2 ± 5.5 |

| New Hampshire | 164 | 48.7 ± 14.1c | 1284 | 52.4 ± 6.3 | 314 | 65.0 ± 11.0c | 1358 | 60.3 ± 6.3 |

| New Jersey | 383 | 65.6 ± 8.8 | 1030 | 62.8 ± 5.5 | 466 | 76.5 ± 8.5 | 1172 | 67.2 ± 5.3 |

| New Mexico | 873 | 64.3 ± 7.2 | 791 | 53.8 ± 8.0 | 867 | 70.4 ± 6.5 | 676 | 64.5 ± 7.1b |

| New York | 973 | 64.1 ± 6.7 | 1512 | 51.8 ± 4.9d | 1277 | 63.0 ± 5.0 | 1853 | 59.5 ± 4.2b |

| North Carolina | 438 | 65.3 ± 13.9c | 986 | 49.8 ± 6.7d | 603 | 58.7 ± 7.2 | 1094 | 57.7 ± 5.8 |

| North Dakota | 244 | 63.1 ± 11.2c | 757 | 49.6 ± 6.6d | 417 | 59.7 ± 10.6c | 1169 | 61.5 ± 6.7b |

| Ohio | 414 | 54.9 ± 9.9 | 906 | 46.4 ± 5.7 | 540 | 50.1 ± 7.8 | 1112 | 57.1 ± 6.3b |

| Oklahoma | 742 | 59.3 ± 7.9 | 565 | 45.1 ± 7.3d | 872 | 54.4 ± 7.4 | 580 | 44.3 ± 8.5 |

| Oregon | 262 | 37.2 ± 10.9c | 1229 | 43.2 ± 5.7 | 354 | 45.0 ± 9.7 | 1450 | 48.1 ± 4.4 |

| Pennsylvania | 782 | 53.3 ± 8.4 | 2221 | 53.4 ± 4.9 | 792 | 57.5 ± 9.3 | 2346 | 67.2 ± 5.8b |

| Rhode Island | 471 | 74.9 ± 10.3c | 1090 | 73.9 ± 6.1 | 496 | 87.1 ± 6.9 | 912 | 81.4 ± 6.2 |

| South Carolina | 627 | 56.4 ± 9.7 | 809 | 42.9 ± 7.1d | 763 | 54.6 ± 7.2 | 873 | 51.1 ± 6.8 |

| South Dakota | 365 | 59.3 ± 9.1 | 716 | 58.1 ± 6.2 | 373 | 80.5 ± 11.2b,c | 749 | 66.5 ± 6.7d |

| Tennessee | 304 | 40.8 ± 11.7c | 1266 | 51.1 ± 5.8 | 341 | 58.7 ± 10.4b,c | 1137 | 56.7 ± 5.5 |

| Texas | 2921 | 51.5 ± 4.9 | 5257 | 54.2 ± 3.5 | 2951 | 56.6 ± 5.5 | 4656 | 56.1 ± 4.4 |

| Utah | 196 | 46.1 ± 14.1c | 901 | 49.8 ± 6.8 | 304 | 47.7 ± 10.6c | 976 | 49.9 ± 5.6 |

| Vermont | 227 | 54.7 ± 12.1c | 1056 | 57.5 ± 6.3 | 405 | 53.6 ± 13.1c | 1284 | 62.6 ± 5.8 |

| Virginia | 290 | 40.7 ± 14.7c | 1419 | 52.2 ± 6.4 | 274 | 59.6 ± 13.0c | 1268 | 63.9 ± 6.5b |

| Washington | 276 | 54.2 ± 12.1c | 986 | 43.2 ± 5.7 | 325 | 57.1 ± 11.8c | 1006 | 56.6 ± 6.1b |

| West Virginia | 467 | 43.1 ± 10.4c | 950 | 52.6 ± 7.3 | 463 | 55.4 ± 8.8 | 935 | 55.8 ± 6.5 |

| Wisconsin | 393 | 54.8 ± 8.4 | 932 | 49.6 ± 5.7 | 414 | 54.4 ± 8.7 | 865 | 55.5 ± 5.6 |

| Wyoming | 288 | 52.9 ± 16.0c | 957 | 42.4 ± 7.7 | 388 | 49.3 ± 11.4c | 998 | 46.3 ± 7.2 |

n is unweighted sample size.

Confidence interval.

Statistically significant difference compared to the 2011–2012 influenza season estimates.

Estimate might be unreliable because CI half-width is >10.

Statistically significant difference compared to the VFC-entitled group in the same influenza season (also bolded).

In the 2011–2012 season, influenza vaccination coverage was similar among VFC-entitled and privately insured children for most socio-demographic groups studied (Table 3). For non-Hispanic white only children, coverage was higher among privately insured compared to VFC-entitled children. For four of the socio-demographic groups (age 13–17 years, MSA principle city, Northeast, and Midwest), coverage was higher among VFC-entitled compared to privately insured children.

Table 3.

Influenza vaccination coverage by select population characteristics, children 6 months–17 years, National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu), 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons.

| Population characteristics | 2011–2012 influenza season

|

2012–2013 influenza season

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFCa-entitled

|

Privately insured

|

VFC-entitled

|

Privately insured

|

||||||

| n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CIb | n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | n | Vaccinated % ± 95% CI | ||

| Age | 6–23 months | 3365 | 71.0 ± 5.1 | 5648 | 76.4 ± 3.5 | 3949 | 73.9 ± 4.5 | 6339 | 80.9 ± 3.0c |

| 2–4 years | 4917 | 64.9 ± 4.1 | 9369 | 63.2 ± 2.8 | 5727 | 62.0 ± 3.3 | 9764 | 68.0 ± 2.6c,d | |

| 5–12 years | 10,930 | 53.4 ± 2.9 | 29,760 | 54.7 ± 1.6 | 14,511 | 56.9 ± 2.1 | 32,880 | 59.4 ± 1.6d | |

| 13–17 years | 6170 | 35.4 ± 3.4 | 13,252 | 30.3 ± 2.5c | 4828 | 45.0 ± 3.5d | 9663 | 42.4 ± 2.3d | |

| Gender | Male | 12,960 | 52.8 ± 2.6 | 30,004 | 51.0 ± 1.7 | 14,893 | 54.3 ± 2.2 | 30,530 | 57.6 ± 1.6c,d |

| Female | 12,422 | 51.2 ± 2.8 | 28,025 | 50.3 ± 1.8 | 14,122 | 57.7 ± 2.4d | 28,116 | 56.9 ± 1.7d | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic, white only | 10,136 | 43.6 ± 2.6 | 42,248 | 48.2 ± 1.3c | 11,426 | 48.5 ± 2.2d | 42,006 | 55.7 ± 1.3c,d |

| Non-Hispanic, black only | 4244 | 55.6 ± 4.2 | 4594 | 50.2 ± 4.3 | 4359 | 56.2 ± 4.0 | 4461 | 58.7 ± 4.4d | |

| Hispanic | 7009 | 58.5 ± 3.8 | 6591 | 60.1 ± 4.1 | 8517 | 62.1 ± 3.1 | 6931 | 59.0 ± 3.9 | |

| Non-Hispanic other/multiple races | 3993 | 50.8 ± 4.8 | 4596 | 54.9 ± 4.2 | 4713 | 57.5 ± 4.0d | 5248 | 64.5 ± 4.2c,d | |

| Metropolitan statistical areas (MSA) | MSA, principle city | 9390 | 57.9 ± 3.2 | 17,451 | 53.3 ± 2.5c | 10,645 | 58.7 ± 2.6 | 18,806 | 60.1 ± 2.2d |

| MSA, non-principle city | 9130 | 49.3 ± 3.1 | 28,887 | 50.8 ± 1.6 | 10,686 | 55.5 ± 2.8d | 27,461 | 56.9 ± 1.7d | |

| Non-MSA | 6862 | 46.4 ± 3.2 | 11,691 | 44.7 ± 2.4 | 7684 | 52.0 ± 2.9d | 12,379 | 52.4 ± 2.4d | |

| Annual income/Poverty levele | Above poverty, ≥$75,000 | 2442 | 46.0 ± 5.6 | 30,349 | 51.0 ± 1.6 | 2878 | 51.9 ± 5.0 | 30,458 | 60.2 ± 1.6c,d |

| Above poverty, <$75,000 | 10,535 | 46.6 ± 2.9 | 20,776 | 46.9 ± 2.0 | 11,578 | 53.7 ± 2.6d | 20,489 | 51.4 ± 2.0d | |

| At or below poverty level | 10,336 | 55.9 ± 2.9 | 3373 | 60.7 ± 5.6 | 11,749 | 58.6 ± 2.4 | 3695 | 63.3 ± 5.1 | |

| Unknown | 2069 | 58.0 ± 6.6 | 3531 | 54.5 ± 4.2 | 2810 | 54.5 ± 5.2 | 4004 | 58.8 ± 4.2 | |

| Regionf | Northeast | 4104 | 62.5 ± 4.0 | 11,260 | 56.5 ± 2.3c | 5039 | 66.1 ± 3.3 | 12,272 | 65.9 ± 2.3d |

| Midwest | 5316 | 50.3 ± 3.3 | 11,767 | 46.0 ± 1.9c | 6035 | 52.3 ± 2.7 | 12,048 | 55.0 ± 2.0d | |

| South | 10,467 | 51.3 ± 2.9 | 21,838 | 50.6 ± 2.0 | 11,478 | 54.9 ± 2.7 | 20,295 | 56.0 ± 1.9d | |

| West | 5495 | 47.8 ± 5.6 | 13,164 | 50.6 ± 3.1 | 6463 | 54.5 ± 4.2 | 14,031 | 54.8 ± 3.1 | |

n is unweighted sample size.

Vaccines for Children program.

Confidence interval.

Statistically significant difference compared to the VFC-entitled group in the same influenza season (also bolded).

Statistically significant difference compared to the 2011–2012 influenza season estimates.

Poverty level was defined based on the reported number of people living in the household and annual household income, and the U.S. Census poverty thresholds.

Classification was based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s census region definition.

Again, for the 2012–2013 season, influenza vaccination coverage was similar among VFC-entitled and privately insured children for most socio-demographic groups studied, but a different pattern was evident (Table 3). For six of the socio-demographic groups (age 6–23 months, age 2–4 years, male, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic other/multiple race, and above poverty ≥$75,000), coverage was higher among privately insured compared to VFC-entitled children. Coverage was not higher among the VFC-entitled children for any of the socio-demographic groups in 2012–2013 season.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that in both influenza seasons studied, VFC-entitled children had similar influenza vaccination coverage to privately insured children overall, and that within the VFC-entitled group uninsured children had influenza vaccination coverage that was at least 10 percentage points lower than the other two VFC-entitled groups of Medicaid and AI/AN children. Two studies have shown that vaccination coverage of other routinely administered vaccines among children 13–17 years was lower for VFC-entitled children compared to privately insured children [12,16]. Another study of children 19–35 months showed differences in vaccination coverage based on insurance status [13]. A similar study showed that vaccination coverage for diphtheria–tetanus–aceullar pertussis, polio, measles–mumps–rubella, Haemophilus influenza type b, varicella, heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV7), and influenza vaccination was lower among VFC-entitled children than for privately insured children [15]. One additional study had shown that, compared to those who were fully insured, children who were underinsured and received vaccinations at a health department clinic had significantly lower vaccination coverage for the varicella and PCV7 vaccines [17]. In our study we could not assess the underinsured group of VFC-eligible children.

As in previous reports of childhood influenza vaccination coverage for the United States, we found large variability in influenza vaccination coverage between states. While several states achieved or surpassed the HP2020 target of 70% coverage, coverage remains low in many states. This variability was observed in both VFC-entitled and privately insured children. It is unknown to us why states vary widely in child influenza vaccination coverage, something that has been seen in the United States since the vaccine was first recommended for all children. The factors likely include varying degrees of programmatic and provider implementation of influenza recommendations, varying parental awareness, attitudes, and access to influenza vaccination services for their children, and other factors. Further study is needed to understand the variability in influenza vaccination coverage between states.

The findings of this study suggest that overall the influenza vaccination coverage among VFC-entitled children is similar to coverage among children who are privately insured; however, efforts are still needed to achieve the HP2020 revised target of 70% coverage in children 6 months–17 years. A striking difference was observed in the uninsured group which had the lowest coverage among the groups compared. These children are eligible for the Vaccines for Children program but may not be aware of the program and may not have a medical home. With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), it is expected that fewer children will be uninsured. The ACA helps make health insurance more available in three primary ways: (1) sets up a Health Insurance Marketplace where consumers may go to compare available insurance plans and enroll in the one they choose, (2) promotes the expansion of Medicaid programs in the states, and (3) reforms insurance market rules (e.g., eliminates denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions)1.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The findings of this study are subject to several limitations. First, influenza vaccination status was based on parental report, not validated with medical records, and, thus, is subject to recall bias. A validity study has shown that parental report (for children) overestimates influenza vaccination coverage and may be more accurate for children who are privately or publicly insured as compared to parent report for uninsured children [25]. Second, NIS-Flu is a telephone survey that excludes households with no telephone service. Non-coverage and non-response bias may remain even after weighting adjustments. Third, we assessed influenza vaccination coverage with at least one dose of vaccination, but children younger than nine years often need two doses to be fully protected against influenza disease [26]. Fourth, our measure of VFC-entitlement included only three of the four VFC-entitlement criteria (Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, and AI/AN), as information was not available to identify underinsured children (likely less than 1%) [11,14] which would lead to a slight underestimation of the percentage of children who are eligible for the VFC program. Lastly, in the NIS-Flu VFC and insurance status for children 6–18 months and 3–12 years (62.5% of the study sample in 2011–2012, 62.6% in 2012–2013) were based upon parental report to a smaller set of questions than what was used for children 19–35 months (NIS-Child) and 13–17 years (NIS-Teen) and, thus, may be subject to misclassification error. To quantify the possible extent of this error, we compared the NIS-Flu insurance variables to unpublished VFC administrative data. The 2013 VFC administrative data was collected using the child age groups <1 year, 1–2 years, 3–6 years, and 7–18 years. For these age groups, respectively, and based on the administrative data, 50.2%, 43.6%, 42.6%, and 32.1% of children in the United States were Medicaid insured in 2013 and 9.2%, 9.2%, 9.2%, and 9.1% were uninsured. An analysis of the NIS-Flu data for the 2012–2013 season by these same age groups (except 6–11 months instead of <1 year) indicated that 32.0%, 38.6%, 28.5%, and 26.9% were Medicaid insured and 5.9%, 4.8%, 6.3% and 7.3% were uninsured. Thus the differences between the NIS-Flu and the administrative data were: 18.2%, 5.0%, 14.1%, and 5.2% for Medicaid and 3.3%, 4.4%, 2.9%, and 1.8% for uninsured. This indicates that the largest amount of underestimation by the NIS-Flu insurance proxy variables occurred for Medicaid insured children <1 year (by 18 percentage points) and 3–6 years (by 14 percentage points), and there was a 5 percentage point or less underestimation for the other age groups for Medicaid and for all age groups for uninsured children based on the NIS-Flu as compared to administrative data. This misclassification of Medicaid status is expected to dilute observed differences in vaccination coverage between VFC-entitled and privately insured children, because some Medicaid-enrolled children will be misclassified as having private health insurance.

5. Conclusions

This study showed no national differences in influenza vaccination coverage by VFC-entitlement status for the two influenza seasons studied. However, children who were uninsured had low vaccination coverage, and large state variability and some variability between demographic variables exists. Although the results are encouraging, influenza vaccination coverage was below the HP2020 target of 70% for almost every socio-demographic group, indicating that improvement of coverage is needed to protect all children from influenza. Increased efforts are needed to implement evidence-based strategies proven to increase vaccination coverage such as a strong recommendation from health care providers, utilization of immunization information systems, provider reminders, standing orders, and community-based interventions such as educational activities and expanded access to vaccination services [27].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nicholas Davis of NORC at the University of Chicago for creating the new weights used in this study and providing the datasets.

Abbreviations

- HP2020

Healthy People 2020

- VFC

Vaccines for Children

- AI/AN

American Indian or Alaska Native

- FQHC

Federally Qualified Health Centers

- RHC

Rural Health Clinics

- NIS-Flu

National Immunization Survey-Flu

- CASRO

Council of American Survey and Research Organizations

- MSA

Metropolitan Statistical Area

- CI

confidence interval

- PCV7

Heptavalent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC.

Author’s contribution

AS conceived the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. He had access to all data and takes the responsibility for their integrity. YZ performed the statistical analyses. TAS, KEK, PJS and JAS participated in data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. TAS and JAS also contributed to the conception of the study and data analysis. All authors have reviewed and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we do not have conflicts of interest relating to this study.

References

- 1.Lu PJ, Santibanez TA, Williams WW, Zhang J, Ding H, Bryan L, et al. Surveillance of influenza vaccination coverage—United States, 2007–08 through 2011–12 influenza seasons. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Oct;62(4):1–28. Surveillance summaries. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 07.03.14];Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2011–12 influenza season. 2013 Aug; Available at 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage1112estimates.htm〉.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 10.01.13];Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2012–13 influenza season. 2013 Sep; Available at 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1213estimates.htm〉.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 09.18.13];Flu estimates for 2009–10 seasonal influenza and influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccination coverage—United States, August 2009 through May, 2010. 2011 May; Available at 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/coverage0910estimates.htm〉.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy people 2020. [accessed 12.17.14];Topics & objectives—immunization and infectious diseases. 2014 Dec; Available at 〈 http://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020IIDandGHProgressReviewData.xlsx〉.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy people 2020. [accessed 04.09.15];Objective development and selection process. 2015 Apr; Available at 〈 https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/history-development/Objective-Development-and-Selection-Process〉.

- 7.Ambrose CS, Toback SL. Improved timing of availability and administration of influenza vaccine through the US Vaccines for Children Program from 2007 to 2011. Clin Pediatr. 2013;52(3):224–30. doi: 10.1177/0009922812470868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith PJ, Santoli JM, Chu SY, Ochoa DQ, Rodewald LE. The association between having a medical home and vaccination coverage among children eligible for the vaccines for children program. Pediatrics. 2005 Jul;116(1):130–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker AT, Smith PJ, Kolasa M. Reduction of racial/ethnic disparities in vaccination coverage, 1995–2011. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2014 Apr;18(63 Suppl):7–12. Surveillance summaries. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993. [accessed 05.05.14];Subtitle D–group health plans. 1993 :326–34. Available at 〈 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-103hr2264enr/pdf/BILLS-103hr2264enr.pdf〉.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 08.07.13];Vaccines for Children Program (VFC) 2013 Apr; Available at 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html〉.

- 12.Lindley MC, Smith PJ, Rodewald LE. Vaccination coverage among U.S. adolescents aged 13–17 years eligible for the Vaccines for Children program, 2009. Pub Health Rep. 2011 Jul-Aug;126(Suppl 2):124–34. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoli JM, Huet NJ, Smith PJ, Barker LE, Rodewald LE, Inkelas M, et al. Insurance status and vaccination coverage among US preschool children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1959–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith PJ, Jain N, Stevenson J, Mannikko N, Molinari NA. Progress in timely vaccination coverage among children living in low-income households. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(5):462–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith PJ, Lindley MC, Rodewald LE. Vaccination coverage among U.S. children aged 19–35 months entitled by the Vaccines for Children program, 2009. Pub Health Rep. 2011 Jul-Aug;126(Suppl 2):109–23. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith PJ, Lindley MC, Shefer A, Rodewald LE. Underinsurance and adolescent immunization delivery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009 Dec;124(Suppl 5):S515–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith PJ, Molinari NA, Rodewald LE. Underinsurance and pediatric immunization delivery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009 Dec;124(Suppl 5):S507–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PJ, Stevenson J, Chu SY. Associations between childhood vaccination coverage, insurance type, and breaks in health insurance coverage. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):1972–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months—United States 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Sep;62(36):733–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith PJ, Hoaglin DC, Battaglia MP, Khare M, Barker LE. Statistical methodology of the National Immunization Survey, 1994–2002. Vital Health Stat 2. 2005 Mar;138:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Response rate—an overview. Deerfield, IL: AAPOR; 2013. [accessed 12.17.14]. Available at 〈 http://www.aapor.org/AAPORKentico/Education-Resources/For-Researchers/Poll-Survey-FAQ/Response-Rates-An-Overview.aspx〉. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim results: state-specific influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccination coverage—United States, October 2009–January 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Apr;59(12):363–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu PJ, Ding H, Black CL. H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccination of U.S. health-care personnel, 2010. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Sep;43(3):282–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 04.16.14];Seasonal influenza (flu) 2013 Sep; Available at 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/index.htm?scid=cs797〉.

- 25.Brown C, Clayton-Boswell H, Chaves SS, Prill MM, Iwane MK, Szilagyi PG, et al. Validity of parental report of influenza vaccination in young children seeking medical care. Vaccine. 2011 Nov;29(51):9488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2013–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Sep;62(RR-07):1–43. MMWR Recommendations and reports. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Guide to Community Preventive Services. [accessed 12.17.14];Increasing appropriate vaccination. 1996 Last updated June 12, 2014. Available at 〈 http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/index.html〉.