Abstract

BACKGROUND

Intermittent treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine is widely recommended for the prevention of malaria in pregnant women in Africa. However, with the spread of resistance to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, new interventions are needed.

METHODS

We conducted a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial involving 300 human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV)–uninfected pregnant adolescents or women in Uganda, where sulfa-doxine–pyrimethamine resistance is widespread. We randomly assigned participants to a sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine regimen (106 participants), a three-dose dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine regimen (94 participants), or a monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine regimen (100 participants). The primary outcome was the prevalence of histopathologically confirmed placental malaria.

RESULTS

The prevalence of histopathologically confirmed placental malaria was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (50.0%) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (34.1%, P = 0.03) or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (27.1%, P = 0.001). The prevalence of a composite adverse birth outcome was lower in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (9.2%) than in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (18.6%, P = 0.05) or the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (21.3%, P = 0.02). During pregnancy, the incidence of symptomatic malaria was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (41 episodes over 43.0 person-years at risk) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (12 episodes over 38.2 person-years at risk, P = 0.001) or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (0 episodes over 42.3 person-years at risk, P<0.001), as was the prevalence of parasitemia (40.5% in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group vs. 16.6% in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group [P<0.001] and 5.2% in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group [P<0.001]). In each treatment group, the risk of vomiting after administration of any dose of the study agents was less than 0.4%, and there were no significant differences among the groups in the risk of adverse events.

CONCLUSIONS

The burden of malaria in pregnancy was significantly lower among adolescent girls or women who received intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine than among those who received sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, and monthly treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine was superior to three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine with regard to several outcomes. (Funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02163447.)

In 2007, more than 30 million pregnancies were estimated to have occurred in areas of sub-Saharan Africa in which Plasmodium falciparum is endemic.1 Malaria during pregnancy is associated with placental malaria, adverse birth outcomes, and complications and death in both the mother and the infant.2,3 In sub-Saharan Africa, malaria during pregnancy is estimated to be the cause of low birth weight in up to 20% of deliveries, leading to more than 100,000 infant deaths annually.2,3 Given the high burden of malaria in this vulnerable population, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the routine implementation of malaria-preventive measures among pregnant women in all countries in Africa in which P. falciparum remains endemic. These measures include the use of long-lasting insecticide–treated bed nets and intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine during pregnancy.4

Earlier studies have shown that intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine during pregnancy is effective at reducing the risk of placental malaria, low birth weight, and maternal illness.5-8 However, resistance to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine has become widespread, especially in East Africa and southern Africa,9 and more recent studies have suggested that the effectiveness of this drug combination as intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy may be compromised10-13; thus, there is a need for evaluation of alternatives to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine for such treatment during pregnancy. Studies of amodiaquine and mefloquine have not shown convincing evidence of superior benefit, and these drugs were found to have more adverse side effects than sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine.14,15

Artemisinin-based combination therapies have been shown to be effective for the treatment of malaria during pregnancy16,17; however, there are limited data evaluating such regimens for use as intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy. Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine is an especially attractive combination therapy, given its prolonged post-treatment prophylactic effect.18 Here, we compare the efficacy and safety of three different regimens as intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy — a regimen of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, a three-dose regimen of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, and a monthly regimen of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine — among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–uninfected adolescent girls and women living in an area of Uganda in which the intensity of malaria transmission and the prevalence of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance are high.

Methods

Trial Setting, Participants, and Oversight

We conducted the trial in Tororo, Uganda, which is an area of high malaria-transmission intensity, with an estimated entomologic inoculation rate of 310 infectious bites per person-year.19 Eligible participants were HIV-uninfected pregnant adolescents or women at least 16 years of age (primigravid or multigravid), who were between 12 and 20 weeks of gestation, as confirmed by ultra-sonography. A complete list of the entry criteria is provided in the trial protocol, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. All trial participants provided written informed consent.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the ethics committees at Makerere University School of Biomedical Sciences, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of California, San Francisco. All the authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses presented and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

Trial Design and Randomization

This was a double-blind, randomized, three-group controlled trial comparing sulfadoxine–pyrimetha-mine, three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, and monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine as intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy. Randomization was performed in a 1:1:1 ratio in permuted blocks of 6 or 12. Pharmacists who were not otherwise involved in the trial were responsible for treatment assignment and the preparation of study agents. Six participants who were randomly assigned to receive three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine were treated with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine because of a transcription error.

Each dose of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (tablets of 500 mg of sulfadoxine and 25 mg of pyrimethamine [Kamsidar, Kampala Pharmaceutical Industries]) consisted of three tablets taken together; doses were administered at three times during the pregnancy (the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group). Each dose of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (tablets of 40 mg of dihydroartemisinin and 320 mg of piperaquine [Duo-Cotecxin, Holley-Cotec]) consisted of three tablets given once a day for 3 consecutive days; doses were administered either three times during the pregnancy (the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piper-aquine group) or once per month (the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group). Participants who were assigned to the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group or the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group received active study agents at 20, 28, and 36 weeks of gestation. Participants who were assigned to the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group received active study agents every 4 weeks starting at 16 or 20 weeks of gestation. Placebos of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine and dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine were used such that every 4 weeks, participants received the same number of pills with the same appearance. Administration of the first daily doses of active agents or placebo were directly observed in the clinic, and the second and third daily doses were administered at home. Additional details regarding the administration of the study agents are provided in the trial protocol.

Trial Procedures

At enrollment, participants received a net treated with long-lasting insecticide, underwent a standardized examination, and had blood samples collected. Participants received all their medical care at a study clinic that was open every day. Routine visits were scheduled every 4 weeks and included collection of blood for dried blood spots to be used for future molecular testing; routine laboratory testing (complete blood count and measurement of alanine aminotransferase levels) was performed every 8 weeks. Participants were encouraged to come to the clinic any time they were ill. Those who presented with a documented fever (tympanic temperature, ≥38.0°C) or history of fever in the previous 24 hours had blood collected for a thick blood smear. If the smear was positive for parasites, malaria was diagnosed and treated with artemether–lumefantrine.

Participants were encouraged to deliver at the hospital adjacent to the study clinic. Participants who delivered at home were visited by trial staff at the time of delivery or as soon as possible afterward. At delivery, a standardized assessment was completed, including evaluation of the neonate for congenital anomalies, measurement of birth weight, and collection of biologic specimens, including placental tissue, placental blood, cord blood, and maternal blood. After delivery, participants were followed for 6 weeks. Adverse events were assessed and graded according to standardized criteria at every visit to the study clinic.20 Electrocardiography was performed to assess corrected QT (QTc) intervals with the use of the Fridericia’s formula in 42 participants just before their first daily dose of study agents and 3 to 4 hours after their third daily dose of study agents when they reached 28 weeks of gestation.

Laboratory Procedures

Blood smears were collected from febrile participants during pregnancy and from placental, cord, and maternal blood at delivery. Blood smears were stained with 2% Giemsa and read by experienced laboratory technologists. A blood smear was considered to be negative when the examination of 100 high-power fields did not reveal asexual parasites. For quality control, all slides were read by a second microscopist, and a third reviewer was designated to settle any discrepancy between readings. The rate of agreement between the readers was 98.6% (kappa, 0.96; P<0.001). Blood samples for dried blood spots were obtained from participants at enrollment and every 4 weeks during pregnancy, as well as from placental blood, cord blood, and maternal blood at delivery. Dried blood spots were tested for the presence of malaria parasites with the use of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) kit (Eiken Chemical), as described previously.21 Placental tissues were processed for histologic evidence of placental malaria as described previously.22 Histopathological slides were read in duplicate by two independent readers, and the results were recorded on a standardized case-record form; any discrepant results were resolved by a third reader. The rate of inter-reader agreement was 71.3% (kappa, 0.48; P<0.001). The readers were unaware of both the treatment assignment and the results of previous reads.

Trial Outcomes

The primary outcome was the prevalence of placental malaria, as assessed by the presence of any parasites or malaria pigment detected histopathologically. The histopathological assessment of placenta was also classified according to the standardized system developed by Rogerson et al.23 and according to whether moderate-to-high-grade pigment deposition was present (defined as pigment detected in ≥5% of high-power fields).24 Secondary outcomes included the incidence of symptomatic malaria; the prevalence of parasitemia assessed by means of LAMP; the prevalence of anemia (hemoglobin level, <11 g per deciliter) during pregnancy after the administration of the first dose of study agent; the prevalence of parasitemia at delivery assessed by means of microscopy and LAMP in samples of placental, cord, and maternal blood; and adverse birth outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, low birth weight (<2500 g), preterm delivery (<37 weeks), congenital anomaly, and a composite of any of these birth outcomes. For participants who gave birth to twins, the delivery outcomes were based on whether the outcome was present in either child or in the placenta. Measures of safety and side-effect profiles included the prevalence of vomiting after administration of study agents and the incidence of adverse events after the initiation of study agents through 6 weeks post partum.

Statistical Analysis

To test the hypothesis that the use of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy with either three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine or monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine would be associated with a lower risk of histopatho-logically confirmed placental malaria than that associated with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, we assumed a prevalence of placental malaria of 62% in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group on the basis of previous data and calculated that a sample size of 300 would be required for the study to have 80% power to show a 33% lower prevalence with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, at a two-sided significance level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata software, version 12 (StataCorp). All analyses were performed in the modified intention-to-treat population, which included all participants who were randomly assigned to a treatment group and who had outcomes of interest that could be evaluated. Comparisons of simple proportions were made with the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Comparisons of proportions with repeated measures were made with generalized estimating equations, with the use of log-binomial regression and robust standard errors. Comparisons of incidence measures were made with a negative binomial regression model. All P values were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Trial Participants and Follow-up

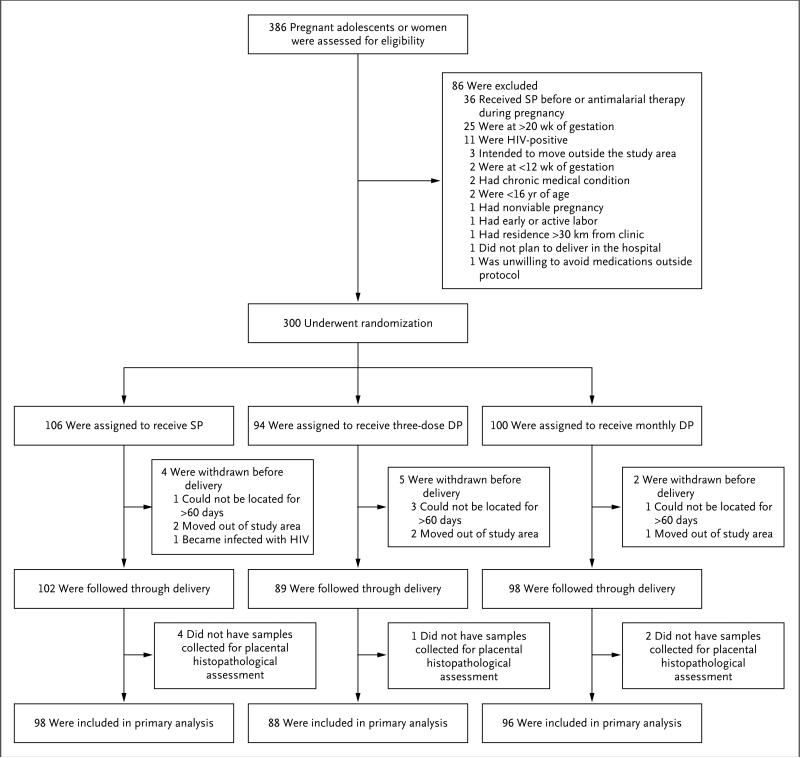

From June through October 2014, a total of 386 adolescent girls and women were screened, and 300 were enrolled and underwent randomization; 106 enrollees were assigned to the sulfa-doxine–pyrimethamine group, 94 to the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group, and 100 to the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics were similar among the three treatment groups (Table 1). The mean age at enrollment was 22 years, 69% of the participants were enrolled at 16 weeks of gestation or earlier, 37% were primigravid, 87% reported owning a long-lasting insecticide–treated net, and 57% had malaria parasites detected by LAMP. A total of 289 participants (96.3%) were followed through delivery, and 282 (94.0%) had placental tissue collected for histopathological assessment (Fig. 1). Eight participants gave birth to twins; four of these twin births had dichorionic placentas.

Figure 1. Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

DP denotes dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, and SP sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants at Enrollment.*

| Characteristic | Sulfadoxine–Pyrimethamine (N = 106) | Three-Dose Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine (N = 94) | Monthly Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 21.3±3.6 | 22.2±4.3 | 22.6±4.0† |

| Gestation — wk | 15.2±2.0 | 15.4±2.0 | 15.5±2.1 |

| 12 to 16 wk — no. (%) | 75 (70.8) | 65 (69.2) | 67 (67.0) |

| >16 to 20 wk — no. (%) | 31 (29.3) | 29 (30.9) | 33 (33.0) |

| Gravidity — no. (%)‡ | |||

| 1 | 42 (39.6) | 33 (35.1) | 36 (36.0) |

| 2 | 32 (30.2) | 28 (29.8) | 28 (28.0) |

| ≥3 | 32 (30.2) | 33 (35.1) | 36 (36.0) |

| Bed-net ownership — no. (%) | |||

| None | 13 (12.3) | 8 (8.5) | 9 (9.0) |

| Untreated net | 1 (0.9) | 6 (6.4) | 2 (2.0) |

| Long-lasting insecticide–treated net | 92 (86.8) | 80 (85.1) | 89 (89.0) |

| Household wealth index — no. (%) | |||

| Lowest third | 38 (35.9) | 29 (30.9) | 33 (33.0) |

| Middle third | 32 (30.2) | 37 (39.4) | 31 (31.0) |

| Highest third | 36 (34.0) | 28 (29.8) | 36 (36.0) |

| Weight — kg | 55.4±6.8 | 55.6±7.0 | 55.5±7.5 |

| Height — cm | 162.8±6.8 | 162.5±6.7 | 162.3±7.7 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| White-cell count per mm3 | 6036±2070 | 6279±1713 | 6040±1572 |

| Neutrophil count per mm3 | 3330±1477 | 3558±1304 | 3351±1175 |

| Platelet count per mm3 | 198,906±60,665 | 201,809±67,358 | 195,840±59,593 |

| Hemoglobin level — g/dl | 11.8±1.5 | 11.9±1.1 | 12.0±1.4 |

| Alanine aminotransferase level — lU/liter | 15.4±7.5 | 14.9±5.8 | 14.7±5.6 |

| Detection of malaria parasites by LAMP — no. (%) | 59 (55.7) | 55 (59.1)§ | 57 (57.0) |

There were no significant differences among the groups at baseline, except as noted. LAMP denotes loop-mediated isothermal amplification.

The difference between the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group and the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group was significant (P=0.02).

Gravidity is the number of times a woman has been pregnant (including the pregnancy in this trial).

Data are missing for 1 woman.

Efficacy Outcomes

At delivery, the prevalence of any histopathologically confirmed placental malaria was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (50.0%) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (34.1%, P = 0.03) or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (27.1%, P = 0.001) (Table 2). All 105 placentas that were positive for placental malaria had pigment in fibrin that was indicative of past infection, but only 7 had parasites indicative of concomitant active infection. The prevalence of moderate-to-high-grade pigment deposition was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (33.7%) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (18.2%, P = 0.02) or the monthly dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine group (8.3%, P<0.001) (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). When only primigravid participants were considered, the prevalence of any histologically confirmed placental malaria was similar among the three treatment groups, but the prevalence of moderate-to-high-grade pigment deposition was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group than in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (55.6% vs. 20.6%, P = 0.003). The prevalence of histopathologically confirmed placental malaria was much lower among multigravid participants than among primigravid participants, and among multigravid participants, the prevalence of any histopatho-logically confirmed placental malaria and moderate-to-high-grade pigment deposition was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Detection of malaria parasites by means of microscopy in placental and maternal blood was uncommon, with no significant differences among the treatment groups. However, detection of malaria parasites by LAMP in placental and maternal blood was significantly more common in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy Outcomes.*

| Outcome | Sulfadoxine–Pyrimethamine† | Three-Dose Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine | Monthly Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | P Value | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

| Malaria positivity at delivery — no. of participants/total no. (%) | |||||||

| Histopathological assessment of placenta | 49/98 (50.0) | 30/88 (34.1) | 0.68 (0.48-0.97) | 0.03 | 26/96 (27.1) | 0.54 (0.37-0.79) | 0.001 |

| Microscopic assessment of placental blood | 5/96 (5.2) | 3/88 (3.4) | 0.65 (0.16-2.66) | 0.72 | 0/96 | 0 (0-0.46) | 0.06 |

| LAMP assessment of placental blood | 19/96 (19.8) | 3/88 (3.4) | 0.17 (0.05-0.56) | <0.001 | 2/96 (2.1) | 0.11 (0.03-0.44) | <0.001 |

| Microscopic assessment of maternal blood | 5/102 (4.9) | 1/89 (1.1) | 0.23 (0.03-1.93) | 0.22 | 0/97 | 0 (0-0.48) | 0.06 |

| LAMP assessment of maternal blood | 25/102 (24.5) | 3/89 (3.4) | 0.14 (0.04-0.44) | <0.001 | 1/98 (1.0) | 0.04 (0.01-0.30) | <0.001 |

| Microscopic assessment of cord blood | 0/95 | 0/85 | NA | NA | 0/94 | NA | NA |

| LAMP assessment of cord blood | 3/94 (3.2) | 0/85 | 0 (0-0.97) | 0.25 | 0/94 | 0 (0-0.88) | 0.25 |

| Birth outcomes — no. of participants/total no. (%) | |||||||

| Spontaneous abortion | 3/102 (2.9) | 0/89 | 0 (0-1.01) | 0.25 | 0/98 | 0 (0-0.91) | 0.25 |

| Stillbirth‡ | 1/99 (1.0) | 1/89 (1.1) | 1.11 (0.07-17.5) | 1.0 | 1/98 (1.0) | 1.01 (0.06-15.9) | 1.0 |

| Low birth weight‡ | 14/99 (14.1) | 14/89 (15.7) | 1.11 (0.56-2.20) | 0.76 | 8/98 (8.2) | 0.58 (0.25-1.31) | 0.18 |

| Preterm delivery‡ | 8/99 (8.1) | 11/89 (12.4) | 1.53 (0.64-3.63) | 0.33 | 5/98 (5.1) | 0.63 (0.21-1.86) | 0.40 |

| Congenital anomaly‡ | 2/98 (2.0) | 4/89 (4.5) | 2.20 (0.41-11.7) | 0.43 | 0/96 | 0 (0-1.62) | 0.50 |

| Composite adverse birth outcome§ | 19/102 (18.6) | 19/89 (21.3) | 1.15 (0.65-2.02) | 0.64 | 9/98 (9.2) | 0.49 (0.23-1.04) | 0.05 |

| Symptomatic malaria during pregnancy — no. of events (incidence per person-year at risk) | 41 (0.95) | 12 (0.31) | 0.33 (0.17-0.64)¶ | 0.001 | 0 | 0 (0-0.05)¶ | <0.001 |

| Detection of malaria parasites by LAMP during pregnancy — no. of events/total no. (%)∥ | 206/509 (40.5) | 74/445 (16.6) | 0.41 (0.30-0.54) | <0.001 | 26/496 (5.2) | 0.13 (0.08-0.21) | <0.001 |

| Anemia during pregnancy — no. of events/total no. (%)∥** | 94/269 (34.9) | 72/237 (30.4) | 0.87 (0.61-1.23) | 0.43 | 61/258 (23.6) | 0.66 (0.44-0.98) | 0.04 |

NA denotes not applicable.

The sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine group is the reference group for relative-risk calculations.

Only data from participants who delivered after 28 weeks of gestation are included.

Any adverse birth outcome is included.

Values are the incidence rate ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Repeated measures were assessed at the time of all routine visits after administration of study agents.

Anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level lower than 11 g per deciliter.

A total of 72 adverse birth outcomes occurred in 47 participants (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Low birth weight was the most common adverse birth outcome (36 instances), followed by preterm delivery (24), congenital anomaly (6), stillbirth (3), and spontaneous abortion (3). There were no significant differences in individual birth outcomes among the treatment groups, but the risk of any adverse birth outcome was significantly lower in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (9.2%) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (21.3%, P = 0.02); the risk was also lower in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group than that in the sulfa-doxine–pyrimethamine group (18.6%), but the difference was of borderline significance (P = 0.05) (Table 2). A full comparison of efficacy outcomes between the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group and the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group is provided in Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix.

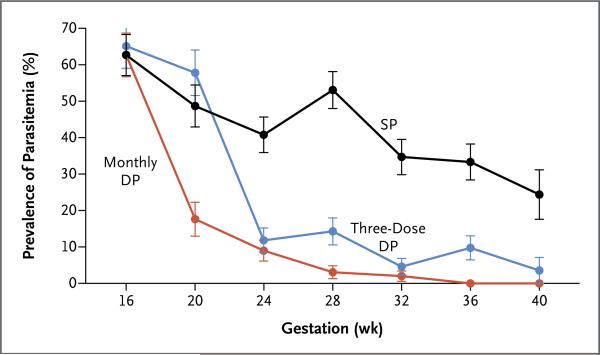

After the initiation of treatment, the incidence of symptomatic malaria during pregnancy was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (41 episodes in 32 participants) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine group (12 episodes in 11 participants, P = 0.001) or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (0 episodes, P<0.001) (Table 2). The prevalence of parasitemia was also significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (40.5%) than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (16.6%, P<0.001) or the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (5.2%, P<0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The risk of maternal anemia was significantly higher in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (34.9%) than in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (23.6%, P = 0.04), but it was not significantly higher than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (30.4%, P = 0.43) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Prevalence of Parasitemia during Pregnancy, According to Week of Gestation.

The data at 16 weeks include only participants who were enrolled on or before this time point (207 adolescent girls or women). For the SP and three-dose DP groups, active drug was given at weeks 20, 28, and 36, and place bo was given at weeks 16, 24, 32, and 40. The prevalence of parasitemia was assessed by means of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP).

Side Effects and Safety Outcomes

Overall, among all the treatment groups, vomiting occurred less than 0.2% of the time after administration of any dose of the study agents, with no significant differences among the treatment groups (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the incidence of any adverse events apart from dysphagia, which was more common in the monthly dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine group than in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group. All episodes of dysphagia were mild in severity, and we are not aware of any previous reports of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine being associated with dysphagia. One grade 3 or 4 adverse event was thought by the investigators to be possibly related to the study agents: an episode of anemia that occurred after both the first and second doses of monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (study agents were subsequently withheld after the second dose) (Table 3). Among 42 participants who underwent electrocardiographic evaluation at 28 weeks of gestation, all pretreatment and post-treatment QTc intervals were within normal limits (≤450 msec), and no clinical adverse events consistent with cardiotoxicity occurred during the course of the study. The median change in QTc interval was greater in the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (20 msec) and monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group (30 msec) than in the sulfa-doxine–pyrimethamine group (5 msec), but these differences were not significant (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 3.

Safety and Adverse Effects.

| Outcome | Sulfadoxine–Pyrimethamine | Three-Dose Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine | Monthly Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine |

|---|---|---|---|

| no. of events/total no. of doses (%) | |||

| Vomiting after administration of study agent | |||

| Observed after administration of first dose in clinic | 2/617 (0.3) | 0/542 | 1/594 (0.2) |

| Reported after administration of second or third dose at home | 2/1222 (0.2) | 0/1067 | 5/1180 (0.4) |

| no. of events (incidence per person-year at risk) | |||

| Adverse event of any severity* | |||

| Abdominal pain | 172 (3.14) | 122 (2.52) | 132 (2.47) |

| Cough | 94 (1.72) | 71 (1.47) | 77 (1.44) |

| Headache | 90 (1.64) | 70 (1.45) | 78 (1.46) |

| Chills | 21 (0.38) | 14 (0.29) | 12 (0.22) |

| Diarrhea | 12 (0.22) | 10 (0.21) | 13 (0.24) |

| Malaise | 16 (0.29) | 9 (0.19) | 8 (0.15) |

| Dysphagia | 9 (0.16) | 2 (0.04) | 14 (0.26)† |

| Vomiting | 8 (0.15) | 8 (0.17) | 8 (0.15) |

| Nausea | 2 (0.04) | 4 (0.08) | 2 (0.04) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (0.05) | 2 (0.04) | 2 (0.04) |

| Anorexia | 2 (0.04) | 0 | 4 (0.07) |

| Grade 3 or 4 adverse event | |||

| Anemia | 12 (0.22) | 4 (0.08) | 6 (0.11) |

| Congenital anomaly | 2 (0.04) | 4 (0.08) | 0 |

| Stillbirth | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.02) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (0.04) | 0 | 0 |

| Vaginal bleeding during second trimester | 1 (0.02) | 0 | 0 |

| Retained products of conception | 0 | 1 (0.02) | 0 |

| Preeclampsia | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.02) |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.02) |

| Pyelonephritis | 0 | 1 (0.02) | 0 |

| Respiratory distress | 0 | 1 (0.02) | 0 |

| All grade 3 or 4 adverse events | 18 (0.33) | 12 (0.25) | 9 (0.17) |

| Grade 3 or 4 adverse events possibly related to study agents | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.02) |

| All serious adverse events | 6 (0.11) | 9 (0.19) | 4 (0.07) |

Only categories with at least 5 total events are included.

P=0.02 for the comparison of monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine versus three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine.

Discussion

In this double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy, the burden of malaria during pregnancy in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group (the current standard of care) was almost 1 episode of symptomatic malaria per person-year, with a prevalence of parasitemia higher than 40% during pregnancy, a prevalence of histopathologically confirmed placental malaria of 50%, and a prevalence of any adverse birth outcome of almost 20%. The incidence of symptomatic malaria, the prevalence of parasitemia during pregnancy, and the prevalence of histopathologically confirmed placental malaria were lower in the group that received the three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine regimen and in the group that received the monthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine regimen than in the group that received the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine regimen. In addition, the risk of maternal anemia was lower — and the risk of any adverse birth outcome was marginally lower — in the monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine group than in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group. Monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine was associated with a lower incidence of symptomatic malaria, a lower prevalence of parasitemia during pregnancy, less moderate-to-high-grade placental pigment deposition, and a lower risk of any adverse birth outcome than was three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, which suggests that the efficacy of this drug combination is higher with more frequent dosing. All three treatment regimens were associated with a low risk of vomiting, and there were no clinically significant differences in the rates of adverse events.

The burden of malaria in the sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine group was not surprising, given the prevalence of molecular markers of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance in East Africa.9,25-27 Observational studies from East Africa suggested that the use of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine as intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy provided minimal or no benefit,10,12,13 and in a randomized trial involving young Ugandan children, intermittent preventive treatment with monthly sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine provided no protection against malaria.28 A few controlled trials have evaluated alternatives to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, including amodiaquine and mefloquine, for intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy; however, they have not shown convincing evidence of higher efficacy, and the drugs had a poor side-effect profile.14,15

Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine has been shown to be effective for the treatment of malaria in pregnant and nonpregnant populations29,30 and for the prevention of malaria in children and nonpregnant adults.28,31 In addition to our trial, one other trial has evaluated the use of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy in an area of western Kenya with high levels of resistance to sulfa-doxine–pyrimethamine.32 In that trial, HIV-uninfected pregnant women were randomly assigned to receive intermittent screening and treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine or intermittent preventive treatment with a median of three doses of either dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine or sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine. Intermittent screening and treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine was not found to be a suitable alternative to intermittent treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine; however, intermittent treatment with dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine was associated with a lower prevalence of malaria infection at delivery and a lower incidence of malaria infection and clinical malaria during pregnancy than was sulfadoxine– pyrimethamine. One of the strengths of our trial was the detailed longitudinal assessment of the risk of malaria during pregnancy and of the way in which effective intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy affects outcomes assessed at delivery. At enrollment, almost 60% of the participants had evidence of asymptomatic parasitemia, which has been associated with an increased risk of placental malaria and adverse birth outcomes.33,34 Dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine was associated with a lower risk of symptomatic malaria and parasitemia than was sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, and treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine was therefore associated with a lower risk of placental malaria. Furthermore, the use of a higher frequency of dosing — every 4 weeks starting as early as 16 weeks of gestation (monthly dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine) rather than every 8 weeks (three-dose dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine) — was associated with an even lower risk of malaria during pregnancy and therefore with a lower risk of moderate-to-high-grade pigment deposition and improvements in birth outcomes. However, among primigravid participants, who are at the highest risk for placental malaria, the risk of low-grade pigment deposition associated with monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine was not lower than that associated with the other two regimens; this suggests the need for effective preventive measures as early in pregnancy as possible.

Safety and side effects are important considerations when preventive drugs are being evaluated for routine use during pregnancy. In this trial, no clinically important differences in the risk of adverse events were observed among the treatment groups. Indeed, in a large systematic review, no safety concerns were identified in association with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine when it is administered for the treatment of malaria and when it is given monthly for the prevention of malaria in young children and adults.28,29,31,35 Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine has been shown to cause prolongation of the QTc interval,36; however, in the limited number of participants in whom the QTc interval was evaluated in this trial, dihydroartemisinin– piperaquine was not associated with any clinically significant prolongation of the QTc interval.

In summary, in a high-transmission setting with widespread resistance to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine during pregnancy resulted in a lower burden of malaria than did treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine. The use of a higher dosing frequency of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (every 4 weeks starting as early as 16 weeks of gestation) provided more protection, which is in line with updated WHO policy recommendations that intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy should be given at every antenatal clinic visit if visits are at least 1 month apart.4 Additional and larger evaluations in different settings are needed to inform im portant questions regarding safety and the potential risks for selection of drug-resistant parasites as a result of an increase in drug pressure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Dellicour S, Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Snow RW, ter Kuile FO. Quantifying the number of pregnancies at risk of malaria in 2007: a demographic study. PLoS Med. 2010;7(1):e1000221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, Menendez C. The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(Suppl):28–35. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyatt HL, Snow RW. The epidemiology and burden of Plasmodium falciparum-related anemia among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(Suppl):36–44. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Updated WHO policy recommendation: intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxinepyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. ( http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/who_iptp_sp_policy_recommendation/en/) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz LJ, Steketee RW, Macheso A, Kazembe P, Chitsulo L, Wirima JJ. The efficacy of antimalarial regimens containing sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and/or chloroquine in preventing peripheral and placental Plasmodium falciparum infection among pregnant women in Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:515–22. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhoeff FH, Brabin BJ, Chimsuku L, Kazembe P, Russell WB, Broadhead RL. An evaluation of the effects of intermittent sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment in pregnancy on parasite clearance and risk of low birthweight in rural Malawi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1998;92:141–50. doi: 10.1080/00034989859979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shulman CE, Dorman EK, Cutts F, et al. Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimetha-mine to prevent severe anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:632–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kayentao K, Kodio M, Newman RD, et al. Comparison of intermittent preventive treatment with chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in Mali. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:109–16. doi: 10.1086/426400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naidoo I, Roper C. Drug resistance maps to guide intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in African infants. Parasitology. 2011;138:1469–79. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutman J, Mwandama D, Wiegand RE, Ali D, Mathanga DP, Skarbinski J. Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimetha-mine during pregnancy on maternal and birth outcomes in Machinga district, Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:907–16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moussiliou A, De Tove YS- S, Doritchamou J, et al. High rates of parasite recrudescence following intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine during pregnancy in Benin. Malar J. 2013;12:195. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arinaitwe E, Ades V, Walakira A, et al. Intermittent preventive therapy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for malaria in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study from Tororo, Uganda. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrington WE, Mutabingwa TK, Kabyemela E, Fried M, Duffy PE. Intermittent treatment to prevent pregnancy malaria does not confer benefit in an area of widespread drug resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:224–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clerk CA, Bruce J, Affipunguh PK, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, amodiaquine, or the combination in pregnant women in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1202–11. doi: 10.1086/591944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González R, Mombo-Ngoma G, Ouédraogo S, et al. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with mefloquine in HIV-negative women: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piola P, Nabasumba C, Turyakira E, et al. Efficacy and safety of artemetherlumefantrine compared with quinine in pregnant women with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: an open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:762–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rijken MJ, McGready R, Boel ME, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine rescue treatment of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in pregnancy: a preliminary report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:543–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White NJ. Intermittent presumptive treatment for malaria. PLoS Med. 2005;2(1):e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamya MR, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, et al. Malaria transmission, infection, and disease at three sites with varied transmission intensity in Uganda: implications for malaria control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:903–12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Division of AIDS (DAIDS) table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events. Version 2.0. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS; Washington, DC: 2014. ( http://rsc.tech-res.com/Document/safetyand pharmacovigilance/DAIDS_AE_Grading_Table_v2_NOV2014.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins H, González IJ, Polley SD, et al. Highly sensitive detection of malaria parasitemia in a malaria-endemic setting: performance of a new loop-mediated iso-thermal amplification kit in a remote clinic in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:645–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natureeba P, Ades V, Luwedde F, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral treatment (ART) versus efavirenz-based ART for the prevention of malaria among HIV-infected pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1938–45. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogerson SJ, Hviid L, Duffy PE, Leke RFG, Taylor DW. Malaria in pregnancy: pathogenesis and immunity. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:105–17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muehlenbachs A, Fried M, McGready R, et al. A novel histological grading scheme for placental malaria applied in areas of high and low malaria transmission. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1608–16. doi: 10.1086/656723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mbonye AK, Birungi J, Yanow SK, et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance markers to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine among pregnant women receiving intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Che-mother. 2015;59:5475–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00507-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matondo SI, Temba GS, Kavishe AA, et al. High levels of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance Pfdhfr-Pfdhps quin-tuple mutations: a cross sectional survey of six regions in Tanzania. Malar J. 2014;13:152. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertin G, Briand V, Bonaventure D, et al. Molecular markers of resistance to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine during intermittent preventive treatment of pregnant women in Benin. Malar J. 2011;10:196. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigira V, Kapisi J, Clark TD, et al. Protective efficacy and safety of three anti-malarial regimens for the prevention of malaria in young Ugandan children: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11(8):e1001689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zani B, Gathu M, Donegan S, Olliaro PL, Sinclair D. Dihydroartemisinin-piper-aquine for treating uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD010927. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poespoprodjo JR, Fobia W, Kenangalem E, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piper-aquine treatment of multidrug resistant falciparum and vivax malaria in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lwin KM, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of monthly versus bimonthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine chemo-prevention in adults at high risk of malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1571–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05877-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desai M, Gutman J, L'lanziva A, et al. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: an open-label, three-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2507–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cottrell G, Moussiliou A, Luty AJ, et al. Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum infections are associated with maternal anemia, premature births, and low birth weight. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1481–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohee LM, Kalilani-Phiri L, Boudova S, et al. Submicroscopic malaria infection during pregnancy and the impact of intermittent preventive treatment. Malar J. 2014;13:274. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nankabirwa JI, Wandera B, Amuge P, et al. Impact of intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piper-aquine on malaria in Ugandan schoolchildren: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1404–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Medicines Agency Eurartesim. 2013 ( http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/001199/human_med_001450.jsp&murl=menus/medicines/medicines.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124&jsenabled=true)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.