Abstract

Recently, a series of novel arylthioindole compounds, potent inhibitors of tubulin polymerization and cancer cell growth, were synthesized. In the present study the effects of 2-(1H-pyrrol-3-yl)-3-((3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)thio)-1H-indole (ATI5 compound) on cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and induction of apoptosis in human T-cell acute leukemia Jurkat cells and their multidrug resistant Jurkat/A4 subline were investigated. Treatment of the Jurkat cells with the ATI5 compound for 48 hrs resulted in a strong G2/M cell cycle arrest and p53-independent apoptotic cell death accompanied by the induction of the active form of caspase-3 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) cleavage. ATI5 treatment also caused non-cell death related mitotic arrest in multidrug resistant Jurkat/A4 cells after 48 hrs of treatment suggesting promising opportunities for the further design of pyrrole-containing ATI compounds as anticancer agents. Cell death resistance of Jurkat/A4 cells to ATI5 compound was associated with alterations in the expression of pro-survival and anti-apoptotic protein-coding and microRNA genes. More importantly, findings showing that ATI5 treatment induced p53-independent apoptosis are of great importance from a therapeutic point of view since p53 mutations are common genetic alterations in human neoplasms.

Keywords: apoptosis, arylthioindoles, drug resistance, gene expression, G2/M arrest, Jurkat leukemia cells, microRNA

Abbreviations

- ATIs

arylthioindoles

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- PARP-1

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Introduction

Tubulin targeting drugs are widely used in current anticancer chemotherapy. There are 2 main classes of microtubule inhibitors. The first class is comprised of agents that alter the microtubule dynamics and structure by preventing tubulin polymerization and includes vinca alkaloids, colchicine, podophyllotoxin, combretastatins, and their semisynthetic or synthetic analogs. The agents of the second class, such as taxanes and epothilones, at high doses stabilize microtubules and promote tubulin polymerization, whereas at low concentrations they inhibit microtubule dynamics.1

All tubulin targeting agents are considered as mitotic poisons, since they interfere with microtubule dynamics and structure leading to cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase.2 Unfortunately, the benefits of antimitotic therapies are often hammered by side effects, particularly myelosuppression, cardiotoxicity and peripheral neurotoxicity. Additionally, the innate and acquired resistance of cancer cells to microtubule targeting drugs also limits their therapeutic use. Therefore, the development of novel effective and less toxic antimitotic cancer-therapeutic drugs remains of great importance.

Recently, novel potent inhibitors of tubulin polymerization and cancer cell growth were synthesized.3,4 The design of the new arylthioindole (ATI) class agents replaced the ester functionality at the position 2 of the indole with a bioisosteric 5-membered heterocyclic nucleus to prevent the hydrolysis by the plasma esterases.5 Molecular modeling studies depicted favorable hydrophobic interactions of these ATI agents with the Lys254 and Leu248 residues located at the colchicine binding site of β-tubulin. The newly synthesized ATI compounds showed effective tubulin inhibitory properties in vitro and potential therapeutic value in cancer treatment. Among them, pyrrole containing ATI, 2-(1H-pyrrol-3-yl)-3-((3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)thio)-1H-indole (ATI5 compound) exhibits potent anti-proliferative and apoptosis-inducing activities in a panel of human solid tumor cell lines, including breast, cervix, prostate, colon, and non-small cell lung cancers. Additionally, it demonstrates positive anticancer activity in cancer drug-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines, including doxorubicin-resistant P-glycoprotein (Pgp)-over-expressing NCI/ADR-RES cells and cisplatin-resistant A2780-CIS cells; however, the effects of ATI5 in human leukemia cells have not yet been studied.3

Based on these considerations, the goals of the present study were: (i) to investigate the effects of the ATI5 compound on human T-cell acute leukemia Jurkat cells and their multidrug-resistant counterpart Jurkat/A4; and (ii) to define the underlying molecular mechanisms associated with ATI5 anticancer action.

Results

Effect of ATI5 on growth inhibition and cell cycle distribution in human leukemia cells

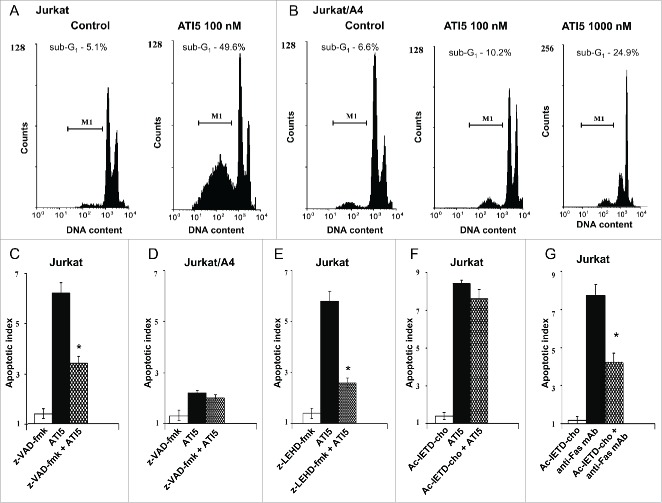

First, the effect of ATI5 and combretastatin A-4, a model tubulin depolymerising agent (Fig. 1A), on cell growth of the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells was examined. Figure 1B shows that both of these agents inhibited effectively growth of the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells.

Figure 1.

Effect of ATI5 treatment on growth inhibition and cell cycle progression in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells. (A) Chemical structure of ATI5 and combretastatin A-4 (CA4P). (B) Growth inhibition of the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with ATI5 or CA4P for 48 hrs. The results are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 ). (C) Cell cycle distribution in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with ATI5 for 48 hrs. After staining with propidium iodide, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in G0/G1 (white bars), S (gray bars) or G2/M phase (hatched bars) is shown.

Since ATI5 and combretastatin A-4 are known antimitotic agents, the cell cycle progression of the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells upon drug treatment was investigated.3,6 Figure 1C shows that treatment of both Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells with ATI5 resulted in accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase with concomitant loss of cells in the G0/G1 phase. This was evidenced by ∼50% increase of G2/M cell-cycle arrest in Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with 100 nM of ATI5 at 24 hrs after treatment. A 10-fold increase in ATI5 concentration further increased the percentage of Jurkat/A4 cells in the G2/M phase. A similar pattern of mitotic arrest was observed in both Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with combretastatin A-4 (data not shown). Furthermore, Table 1 shows that G2/M arrest preceded the induction of apoptosis in ATI5-treated Jurkat cells. This was evidenced by the fact that a time-dependent apoptosis lagged behind the accumulation of Jurkat cells in the G2/M phase.

Table 1.

Cell cycle distribution and apoptotic index in Jurkat cells treated with 100 nM of ATI5.

| Time with ATI5, hrs | Cell cycle phase distribution, % |

Apoptotic index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0/G1 | S | G2/M | ||

| 0 | 43.3 ± 0.6 | 40.1 ± 0.5 | 16.6 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.04 |

| 6 | 19.2 ± 0.4* | 41.4 ± 0.6 | 39.4 ± 0.3* | 1.2 ± 0.03 |

| 24 | 27.7 ± 0.3* | 31.3 ± 0.4* | 41.0 ± 0.4* | 2.4 ± 0.03* |

| 48 | 27.1 ± 0.3* | 20.4 ± 0.5* | 52.5 ± 0.8* | 3.7 ± 0.04* |

The averaged data are given (mean ± SD;

p < 0.01 versus control).

Reversibility of ATI5 cell cycle effect in human leukemia cells

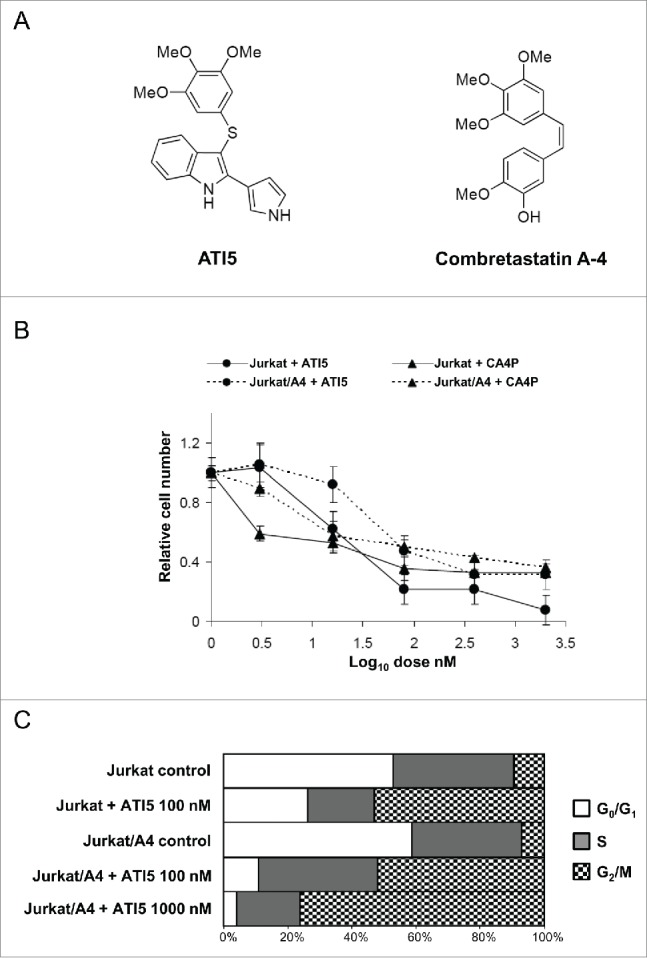

To determine whether or not ATI5-treatment effect on the cell cycle progression is reversible, the Jurkat cells were treated with ATI5 for 3 hrs, rinsed twice with the culture medium, and incubated further in ATI5-free medium. The cell cycle distribution and the hypodiploid cell fraction were analyzed 45 hrs after the cessation of ATI5 exposure and in Jurkat cells that were maintained in the ATI5-containing medium. Figure 2 shows a prominent G2/M arrest of Jurkat cells treated with ATI5 for 3 hrs (Fig. 2B) as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1A) and a complete recovery of the Jurkat cells from G2/M arrest after the cessation of the ATI5 treatment (Fig. 2C), while cells maintained in the presence of ATI5 in the medium for 48 hrs remained in the G2/M phase blocked state (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Reversibility of ATI5 treatment effect on the cell cycle progression in the Jurkat cells. The cell cycle distribution of the Jurkat cells was analyzed after 3 hrs of treatment with ATI5 (B), 45 hrs after the cessation of ATI5 treatment (C), and after 48 hrs of ATI5 exposure (D). Untreated cells served as a control (A). The cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry after the propidium iodide staining. Representative flow cytometry histograms are shown.

Apoptotic activity of ATI5 in human leukemia cells

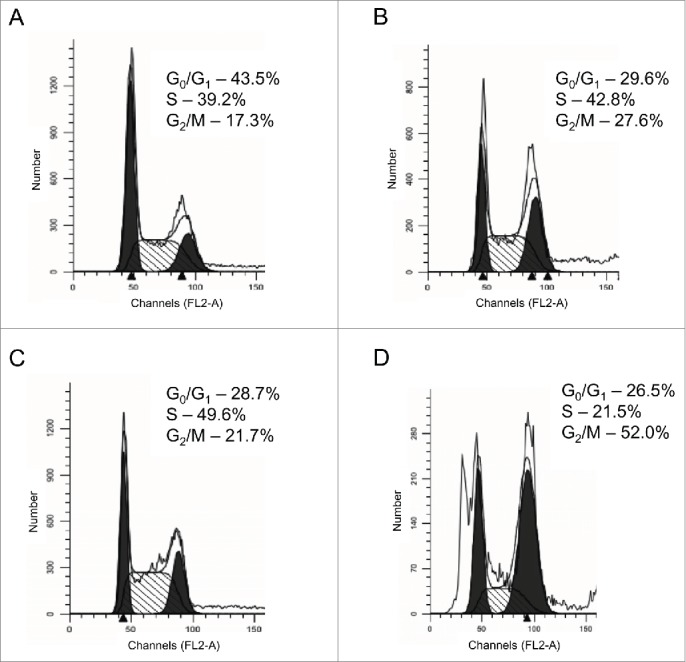

Figure 3 shows that treatment of Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells with ATI5 for 24 hrs resulted in impaired mitoses, formation of micronuclei, and condensed and fragmented nuclei in both cell lines. The characteristic changes resulting from damaged mitotic spindle were analogous in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of ATI5 on morphology of the Jurkat (A) and (B) and Jurkat/A4 (C) and (D) cells. Untreated cells (A) and (C) were used as control. Cells were stained using May–Grünwald–Giemsa technique. Representative images are shown (magnification 100x).

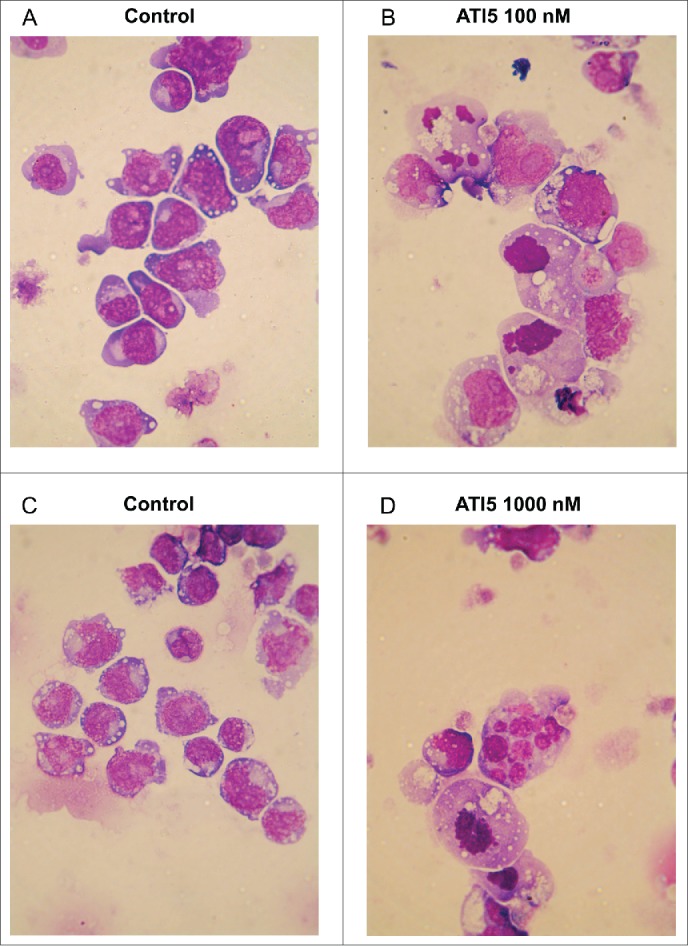

To determine whether or not ATI5 treatment induced DNA fragmentation in the Jurkat cells, DNA content was assessed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Figure 4A shows that treatment of cells with ATI5 at 100 nM for 48 hrs induced a significant increase in the percentage of hypodiploid Jurkat cells (49.6% compared to 5.1% in untreated cells). However, in the Jurkat/A4 cells the same ATI5 dose failed to induce apoptosis, whereas at a concentration of 1000 nM ATI5 caused an increase in the percentage (24.9%) of hypodiploid cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of ATI5 on the induction of apoptosis in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells. Representative flow cytometry histograms showing the percentage of hypodiploid cells in the Jurkat (A) and Jurkat/A4 cells (B). Effect of pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk on ATI5-induced apoptosis in the Jurkat (C) and Jurkat/A4 cells (D). Effect of caspase-8 z-LEHD-fmk inhibitor (E) or caspase-9 inhibitor Ac-IETD-cho (F) on ATI5-induced apoptosis in the Jurkat cells. Effect of caspase-8 z-LEHD-fmk inhibitor on agonistic anti-human Fas (CD95) mAbs-induced apoptotic cell death in the Jurkat cells (G). The percentage of hypodiploid cells was assessed by flow cytometry after the staining with propidium iodide. The results are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 ). * - Significantly different (p < 0.05) as compared to ATI5- or anti-human Fas mAbs-treated cells.

To elucidate the mechanism of the ATI5-induced cell death, the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk was added to the culture medium prior to ATI5 treatment. Figure 4C shows that pre-treatment of Jurkat cells with z-VAD-fmk significantly reduced ATI5-induced apoptosis in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells, but not in Jurkat/A4 cells (Fig. 4D). To investigate further the underlying mechanisms of ATI5-induced apoptosis, Jurkat cells were pre-treated with inhibitors of caspase-8 and caspase-9, major initiators of apoptosis in humans.7 Figure 4E shows that pre-treatment of the Jurkat cells with the inhibitor of caspase-9 z-LEHD-fmk reduced ATI5-induced apoptotic cell death in Jurkat cells. In contrast, pre-treatment of the Jurkat cells with the caspase-8-inhibitor Ac-IETD-cho did not affect ATI5-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4F), while it markedly reduced caspase-8-dependent apoptosis induced by agonistic anti-human Fas monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (Fig. 4G).

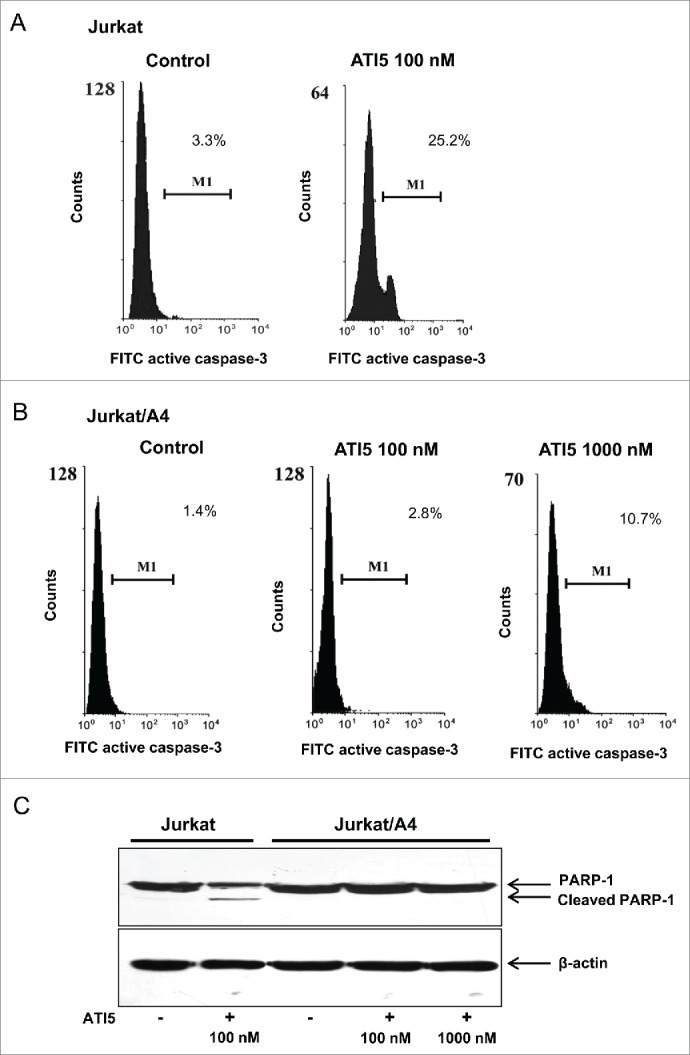

Effect of ATI5 on caspase-3 activation and PARP-1 cleavage

Since caspase-3 activation is recognized as a main executor of apoptosis,7 we examined whether or not ATI5-induced apoptosis in the Jurkat cells was caspase-3–mediated. Jurkat cells were labeled with the caspase-3 C92–605 antibodies that recognize only the active form of caspase-3. Figure 5A shows that the induction of apoptosis in the Jurkat cells treated with 100 nM ATI5 was accompanied by an activation of caspase-3 in 25% of cells 48 hrs after treatment. In contrast, only slight activation of caspase-3 was observed in the Jurkat/A4 cells treated with ATI5 at a dose of 1000 nM (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of ATI5 on caspase-3 activation in the Jurkat (A) or Jurkat/A4 (B) cells. The percentage of cells with active form of caspase-3 in Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with ATI5 for 48 hrs was assessed by flow cytometry as described in the “Materials and Methods.” (C) Analysis of PARP-1 cleavage in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with ATI5. Representative Western blot PARP-1 and β-actin images are shown.

The proteolytic cleavage of PARP-1 by caspases, particularly caspase-3 and caspase-7, is widely used as a marker of caspase activation in apoptotic cells.8 Figure 5C shows that induction of apoptosis in Jurkat cells treated with 100 nM of ATI5 compound was accompanied by PARP-1 cleavage, which was evidenced by the appearance of an 89 kDa PARP-1 fragment confirming an activation of caspase-3 detected by flow cytometry. In contrast, no PARP-1 fragmentation was found in Jurkat/A4 cells exposed to ATI5 even at the highest concentration tested (1000 nM) after 48 hrs of treatment (Fig. 5B).

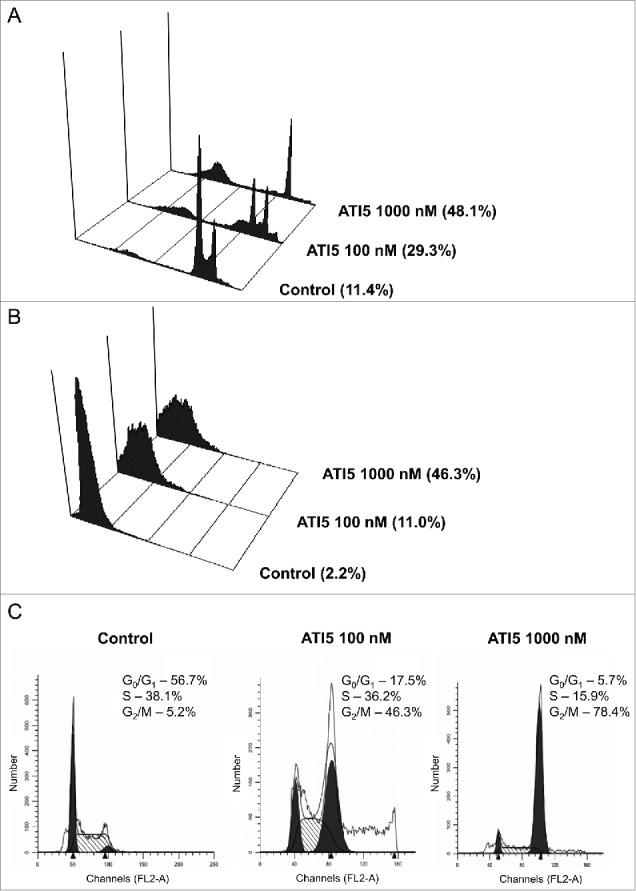

The delayed death of ATI5-treated Jurkat/A4 cells

While treatment of the Jurkat cells with ATI5 at 100 nM for 48 hrs resulted in an induction of apoptosis (Fig. 4A), most of the Jurkat/A4 cells remained viable at this time point even at 1000 nM. Therefore, the effect of prolonged ATI5 treatment on Jurkat/A4 cells was investigated. For this purpose, Jurkat/A4 cells were treated with ATI5 at 100 nM or 1000 nM doses. At 72 hrs of treatment, ATI5-containing medium was replaced by drug-free medium, and cells were incubated for an additional 48 hrs. At the end of incubation, the percentage of viable and hypodiploid cells, percentage of cells with an active form of caspase-3, and cell cycle distribution were determined. Figure 6 demonstrates dose-dependent G2/M arrest and induction of apoptosis in the Jurkat/A4 cells. The dose-dependent increase in the apoptotic cell fraction (Fig. 6A) and number of cells with the active form of caspase-3 (Fig. 6B) suggests an involvement (at least partial) of an apoptotic component in the mechanism of Jurkat/A4 cell death upon exposure to ATI5. Importantly, the Jurkat/A4 cells treated at either dose of ATI5 for 72 hrs were not viable and died in fresh medium within 7–9 d after the exposure (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Delayed effect of ATI5 treatment on the induction of apoptosis, activation of caspase-3, and G2/M arrest in the Jurkat/A4 cells. The cells were treated with ATI5 at 100 nM or 1000 nM. At 72 hrs of treatment, ATI5-containing medium was replaced with drug-free medium, and cells were incubated for additional 48 hrs. The control cells were passaged in 72 hrs as usual and incubated for further 48 hrs. The percentage of hypodiploid cells (A), cells with active form of caspase-3 (B), and the cell cycle distribution (C) was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Gene expression profiles in Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells

To identify potential mechanisms associated with a sensitivity or resistance of the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells to tubulin-binding agents, the gene profiles were investigated. Analysis of the gene expression patterns in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells demonstrated no significant difference in the expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) genes (ABCB1, TAP1, ABCC1, ABCC5 and ABCG1), β-tubulin genes (TUBB, TUBB1, TUBB2A, TUBB3, TUBB4A, and TUBB4B), or genes that encoded specific microtubule-associated proteins (MAP2, MAP4, MAPT) and regulators of the actin cytoskeleton (LIMK1 and LIMK2) in the Jurkat/A4 cells (Table S1). In contrast, the expression of pro-survival and apoptosis-associated genes in the Jurkat/A4 cells was different (the fold-change ≥ 2 and p < 0.05) from that in the Jurkat cells (Table 2). Specifically, the Jurkat/A4 cells exhibited a greater expression of pro-survival genes, including GADD45A, GADD45B, STAT5B, IER3, and SNCA, DNA repair gene CDKN1A, and down-regulation of a number of pro-apoptotic microRNAs, including miR-29b, miR-181, and miR-221.

Table 2.

Expression of apoptosis-associated protein-coding and microRNA genes in resistant Jurkat/A4 cells and Jurkat cells.

| Gene symbol | Gene description |

Fold change, Jurkat/A4 vs Jurkat |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-coding genesa - | ||

| LTB | Lymphotoxin β (TNF superfamily, member 3) | 4.59 |

| GADD45B | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, β | 3.73 |

| CDKN1A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A | 3.48 |

| CD2 | CD2 molecule | 3.03 |

| TNFSF10 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | 3.03 |

| EDAR | Ectodysplasin A receptor | 2.64 |

| MAL | T-cell differentiation protein | 2.46 |

| SNCA | Synuclein | 2.46 |

| SRPK2 | SFRS protein kinase 2 | 2.30 |

| GADD45A | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, α | 2.14 |

| NFKBIA | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, α | 2.14 |

| STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B | 2.14 |

| IER3 (IEX-1) | Immediate early response 3 | 2.00 |

| MAPK8IP2 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein 2 | 2.00 |

| CD70 | CD70 molecule | 2.00 |

| ATF5 | Activating transcription factor 5 | 0.5 |

| BCL2 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 | 0.5 |

| NOTCH2 | Notch 2 | 0.5 |

| BCHE | Butyrylcholinesterase | 0.47 |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium-binding protein A10 | 0.41 |

| TTF1 | Transcription termination factor, RNA polymerase I | 0.35 |

| CD5 | CD5 molecule |

0.29 |

|

microRNA genesb- |

||

| MIR34a | miR-34a | 2.59 |

| MIR221 | miR-221 | 0.42 |

| MIR200b | miR-200b | 0.61 |

| MIR181a | miR-181a | 0.39 |

| MIR29b | miR-29b | 0.62 |

| MIR22 | miR-22 | 0.61 |

| MIR21 | miR-21 | 0.68 |

Only protein-coding genes demonstrating at least 2-fold change are presented;

only microRNAs demonstrating at least 1.5-fold change are presented.

Discussion

In the present study we investigated mechanisms associated with the antileukaemic activity of a new ATI5 antimitotic agent, which prevents tubulin polymerization by affecting microtubule stability and function in human T-cell acute leukemia Jurkat cells and their counterpart drug-resistant Jurkat/A4 cells.3 ATI5 exerts its antimitotic effects through binding to the colchicine site on β-tubulin.9 In contrast to a number of anticancer drugs, inhibitors of tubulin polymerization, including combretastatin A-4, a model tubulin depolymerising agent, ATI5 possesses several advantages such as a greater metabolic stability, aqueous solubility, and rapid absorption after oral administration, high oral bioavailability, and low clearance.3,4

The results of this study demonstrate that ATI5 inhibited proliferation of both Jurkat and drug-resistant Jurkat/A4 cells in a dose-dependent manner with a similar growth inhibitory effect by causing G2/M cell cycle arrest. These findings are in good agreement with our previous study of cell cycle effects of the conformationally restricted 1,2,3-triazole analog of combretastatin A-4 in both Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells.10 A similar effect of ATI5 has been demonstrated earlier in HeLa cells.3 Thus, ATI5 exhibits strong antimitotic activity toward cancer cells of various origins, including leukemic cells.

In addition to the G2/M cell cycle arrest, treatment of the Jurkat cells with ATI5 resulted in the induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis mediated by an activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3. This was evidenced by the fact that pre-treatment of Jurkat cells with caspase-9 inhibitor reduced apoptosis in ATI5-treated cells. Additionally, a great number of ATI5-treated Jurkat cells contained activated caspase-3 that was accompanied by proteolytic cleavage of PARP-1. This corresponds to previous report by Semenova et al.11 showing that cell death induced by antimitotic 4-azapodophyllotoxin derivatives is associated with caspase-9 activation.

The results of this and previous studies, suggest the following sequence of molecular events resulting in cell death of the Jurkat cells exposed to ATI5 compound: ATI5 binds to β-tubulin causing depolymerization of microtubules, which in turn results in cell-cycle block at the G2/M phase, mitotic arrest, and, finally, activation of caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death by intrinsic apoptotic pathways.3 This suggestion is supported by a report by Rovini et al.12 showing an association between microtubule binding and apoptosis induction. In particular, antitubulin agents may release microtubule-related apoptotic regulators from microtubules toward mitochondria, or interact directly with mitochondrial components.12 Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms coupling G2/M arrest induced by microtubule-targeting agents and the initiation of apoptosis remain to be elucidated.

The analysis of the mechanisms of the Jurkat/A4 cell resistance to ATI5 compound as well as to other chemotherapeutic drugs with different modes of action was the second major aim of our study.13 While the antimitotic effect of ATI5 in the Jurkat/A4 cells was as strong as in parental Jurkat cells, cytotoxicity and pro-apoptotic activity of this compound in the drug-resistant Jurkat/A4 cells were significantly lower. The gene expression analysis indicates that the resistance of Jurkat/4 cells to ATI5 was rather associated with alterations in the expression of pro-survival and anti-apoptotic genes than with changes in the expression of β-tubulin isotype or microtubule-regulating genes or over-expression of drug efflux ABC transporters. This suggestion is supported by up-regulation of several key pro-survival genes in the drug-resistant Jurkat/A4 cells. For instance, it has been reported that the LTB gene, the most up-regulated gene in the Jurkat/A4 cells, is over-expressed in human leukemia cells and promotes growth of tumor cells.14-16 A number of over-expressed genes, including GADD45A, GADD45B, STAT5B, and IER3 (IEX-1) protect haematopoietic cells from apoptosis induced by DNA damaging agents.17-20 Specifically, Hoffman and Liebermann21 have reported that Gadd45-deficient cells are more sensitive to apoptosis and pro-survival functions of Gadd45 in haematopoietic cells involving activation of the GADD45a-p38-NF-кB survival pathway and GADD45b mediated inhibition of the stress response MKK-JNK apoptotic pathway. Several studies have demonstrated that over-expression of STAT5B suppresses apoptosis in leukemia cells,22 while drug-induced or targeted inhibition of STAT5A and STAT5B caused the induction of apoptosis.23-25 Furthermore, Akilov et al.26 have shown that resistance to TNF-α-induced apoptosis is associated with up-regulation of IER3. More importantly, a report by Li and Lee27 demonstrating that the anti-apoptotic property of SNCA is associated with attenuation of caspase-3 activity is consistent with an increased expression of the SNCA gene and absence of caspase-3 activation in the Jurkat/4 cells. Additionally, several proapoptotic microRNAs, miR-29b, miR-181, and miR-221, were down-regulated in the Jurkat/4 cells. Another important finding of this study is a marked up-regulation of pro-apoptotic miR-34a in the drug-resistant Jurkat/A4 cells without an activation of apoptosis. It is well-known that miR-34a is involved in the miR-34a-p53 tumor suppressor apoptotic network28; however, since the Jurkat cells and their derivative Jurkat/A4 cells do not have a functional p53, up-regulation of miR-34a in the Jurkat/A4 cells did not impact p53-dependent apoptosis.28

In summary, the results of the present study show that the ATI5 compound exhibits a strong p53-independent antimitotic and apoptosis-inducing activity in human T-cell acute leukemia Jurkat cells. ATI5 caused also the mitotic arrest in the multidrug resistant Jurkat/A4 cells that do not over-express Pgp suggesting the promising opportunities for further design of pyrrole-containing ATI compounds as anticancer agents. Furthermore, our findings showing that ATI5-induced apoptosis did not require the presence of functional p53, since Jurkat cells have a mutated p53,29 are of great importance from a therapeutic point of view since p53 mutations are common genetic alterations in human neoplasms.30

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Two-(1H-Pyrrol-3-yl)-3-((3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)thio)-1H-indole (designated as compound ATI5) was synthesized at the Sapienza University (Roma, Italy) according to the procedure described in La Regina et al.3 Combretastatin A-4 disodium phosphate was obtained from OXiGENE Inc.. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, D8418), propidium iodide (P4170), ribonuclease A (R4875), and pancaspase peptide inhibitor z-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone (z-VAD-fmk, C2105) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ac-IETD-cho (caspase-8 inhibitor, 556554) and z-LEHD-fmk (caspase-9 inhibitor, 550381) were obtained from BD PharMingen. Stock solution of ATI5 was prepared in DMSO at 10 mM concentration, stored at −20°C and diluted to specified final concentrations in culture medium before incubation. Stock solution of combretastatin A-4 (10 mM) was prepared in sterile distilled water. The agonistic anti-human Fas (CD95) monoclonal antibodies were kindly gifted by Prof. Svitlana Sidorenko (Institute of Experimental Oncology, Pathology and Radiobiology, Kyiv, Ukraine).

Cell culture

The Jurkat human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line was obtained from the National Collection of Cell Lines of the Institute of Experimental Pathology, Oncology and Radiobiology (Kyiv, Ukraine). The drug-resistant Jurkat/A4 cell subclone was generated by selection of Jurkat cells exposed repeatedly to high doses (125–250 ng/mL) of agonistic anti-Fas monoclonal antibodies13 and was cross-resistant to apoptosis induced by a broad spectrum of chemotherapeutic drugs, X-ray exposure, and photodynamic therapy.13,31-33

The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, R8758) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich, F7524) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cultures were passaged every 3–4 d immediately upon reaching maximum cell density.

Cell morphology

Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells were cytospinned and stained using the May–Grünwald–Giemsa technique. Light microscopy images (magnification 100×) were recorded by Axiostar 2 plus Axio Cam MRc5 (Carl Zeiss).

Cytotoxicity and growth inhibition assays

Cell viability was evaluated in 96-well microplates by direct counting of trypan blue dye-excluding cells.34 Based on the preliminary cytotoxicity assays, ATI5 was used at a concentration of 100 nM in all experiments in Jurkat cells; 10-fold higher concentration of ATI5 was arbitrary selected for the experiments in Jurkat/A4 cells. ATI5 was added at the exponential growth phase at the concentrations of 3 nM–2000 nM. Combretastatin A-4 served as a reference compound. Control samples were incubated with DMSO at the concentrations not exceeding 0.1% (vol/vol). The experiments were repeated twice, and cells at each point were tested in triplicate.

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis

Cell cycle and induction of apoptosis in the Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells treated with ATI5 were assessed by flow cytometry. The cells were re-suspended in hypotonic lysis buffer containing 0.1% sodium citrate, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 5 μg/ml propidium iodide. Ribonuclease A (250 μg/ml) was added to each sample, and the cells were incubated for 15 min at 37° C. The fluorescence of propidium iodide-stained cells was measured by flow cytometry using a BDTM FACSCalibur system (Becton Dickinson). Forward and sideways light scattering provided the elimination of dead cells and debris. Data were analyzed using ModFit LT 2.0 (Verity Software House), or CellQuest software package (BD Biosciences). The induction of apoptosis was determined by the appearance of a sub-G1 (<2 N ploidy) cell population and the apoptotic index was calculated as a ratio: treatment-induced hypodiploid cells (%)/spontaneous hypodiploid cells in untreated cells (%).

Caspase activation

To investigate caspase involvement in the compound-induced cell death, cells were pretreated with pan-caspase, caspase-8 or caspase-9 inhibitors (z-VAD-fmk, Ac-IETD-cho or z-LEHD-fmk) at 50 μM, 40 μM, and 30 μM, respectively for 3 hrs prior to exposure to ATI5. Jurkat cells, treated with agonistic anti-human Fas (CD95) mAbs at concentration of 1 μg/ml for 18 hrs, served as control for an induction of caspase-8-dependent apoptosis. The percentage of cells with the active form of caspase-3 was assessed by flow cytometry using a Caspase-3, Active Form, mAb Apoptosis Kit: FITC (BD Biosciences, 550480). Prior to direct immunolabelling, the cells were permeabilized according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

Forty eight hours after incubation with ATI5 or combretastatin A-4, cells were harvested, centrifuged, and washed twice with ice cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellets were re-suspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, and 150 mM NaCl, with freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, 04693116001) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The cell lysates were then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min and protein concentration was determined as described previously.35 Equal amounts of protein were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12% acrylamide gels) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes Immobilon-P (Millipore, IPVH15150) by electroblotting. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 followed by incubation with primary antibodies against of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1; BD Biosciences, 556494) for 2 hrs at room temperature. Then anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate (Promega, W4021) were added to membranes for 60 min. Membranes were visualized using Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, RPN2108). To confirm equal protein loading, each membrane was probed with anti-β-actin antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, A1978).

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression data in Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells from our data set obtained with U133A chips (Affymetrix, 510681) were extracted as .txt files from the MIAMExpress Database (accession number E-MEXP-530).36 The arbitrary 2-fold change cutoff was set for analysis to determine differentially expressed genes in Jurkat/A4 and Jurkat cells by using the one-sided Wilcoxon's rank test.

RNA extraction and microRNA expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from Jurkat and Jurkat/A4 cells using miRNAeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, 217004) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The level of microRNA (miRNA) gene transcripts was determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using TaqMan miRNA assays (Life Technologies, 4427975) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNU48 was used as an endogenous control. The relative amount of each microRNA was measured using the 2−ΔΔCt method.37 All qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were conducted by a one-way analysis of variance, with pair-wise comparisons being conducted by the Student-Neuman-Keuls test.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent those of the US. Food and Drug Administration.

Author contributions

A.P., M.Z. and L.K. carried out the cellular, flow cytometry experiments and immunoblotting. V.T. performed the microRNA expression analysis. D.B. performed the gene profiling. K.M. analyzed and interpreted most of the data. R.S. synthesized and characterized ATI5 compound. I.P.P. designed the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Andrey Mikhailov (Turku Center for Biotechnology, University of Turku/Abo Akademi University, Turku, Finland) for DNA-microarray analysis and Prof. Svitlana Sidorenko for anti-human Fas (CD95) monoclonal antibodies. We also thank Dr. Marina Semenova (N.K. Kol'tsov Institute of Developmental Biology, Moscow, Russian Federation) for critical reading of the manuscript and numerous discussions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Grant # F53.4/056 from State Fund for Fundamental Research (DFFD), Ukraine.

References

- 1.Beckers T, Mahboobi S. Natural, semisynthetic and synthetic microtubule inhibitors for cancer therapy. Drugs Future 2003; 28:767-85; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1358/dof.2003.028.08.744356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Sham HL. Discovery and development of antimitotic agents that inhibit tubulin polymerization for the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2002; 12:1663-702; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1517/13543776.12.11.1663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Regina G, Bai R, Rensen W, Coluccia A, Piscitelli F, Gatti V, Bolognesi A, Lavecchia A, Granata I, Porta A, et al.. Design and synthesis of 2-heterocyclyl-3-arylthio-1H-indoles as potent tubulin polymerization and cell growth inhibitors with improved metabolic stability. J Med Chem 2011; 54:8394-406; PMID:22044164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jm2012886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Regina G, Bai R, Rensen WM, Di Cesare E, Coluccia A, Piscitelli F, Famiglini V, Reggio A, Nalli M, Pelliccia S, et al.. Toward highly potent cancer agents by modulating the C-2 group of the arylthioindole class of tubulin polymerization inhibitors. J Med Chem 2013; 56:123-49; PMID:23214452; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jm3013097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciapetti P, Giethlen B. Molecular variations based on isosteric replacement. Carboxylic esters bioisosteres In: The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry, 3rd ed. Wermuth CG, ed. Elsevier Ltd, Oxford, 2008: 310−3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tron GC, Pirali T, Sorba G, Pagliai F, Busacca S, Genazzani AA. Medicinal chemistry of combretastatin A4: present and future directions. J Med Chem 2006; 49:3033-44; PMID:16722619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jm0512903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Dawar S, Kumar S. Old, new and emerging functions of caspases. Cell Death Differ 2015; 22:526-39; PMID:25526085; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2014.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Los M, Mozoluk M, Ferrari D, Stepczynska A, Stroh C, Renz A, Herceg Z, Wang ZQ, Schulze-Osthoff K. Activation and caspase-mediated inhibition of PARP: A molecular switch between fibroblast necrosis and apoptosis in death receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell 2002; 13:978-88; PMID:11907276; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Martino G, La Regina G, Coluccia A, Edler MC, Barbera MC, Brancale A, Wilcox E, Hamel E, Artico M, Silvestri R. Arylthioindoles, potent inhibitors of tubulin polymerization. J Med Chem 2004; 47:6120-3; PMID:15566282; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jm049360d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demchuk DV, Samet AV, Chernysheva NB, Ushkarov VI, Stashina GA, Konyushkin LD, Raihstat MM, Firgang SI, Philchenkov AA, Zavelevich MP, et al.. Synthesis and antiproliferative activity of conformationally restricted 1,2,3-triazole analogues of combretastatins in the sea urchin embryo model and against human cancer cell lines. Bioorg Med Chem 2014; 22:738-55; PMID:24387982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenova MN, Kiselyov AS, Tsyganov DV, Konyushkin LD, Firgang SI, Semenov RV, Malyshev OR, Raihstat MM, Fuchs F, Stielow A, et al.. Polyalkoxybenzenes from plants. 5. Parsley seed extract in synthesis of azapodophyllotoxins featuring strong tubulin destabilizing activity in the sea urchin embryo and cell culture assays. J Med Chem 2011; 54:7138-49; PMID:21916509; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jm200737s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rovini A, Savry A, Braguer D, Carré M. Microtubule-targeted agents: When mitochondria become essential to chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1807:679-88; PMID:21216222; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokolovskaya AA, Zabotina TN, Blokhin DY, Inshakov AN, Mikhailov AD, Kadagidze ZG, Baryshnikov AY. CD95-deficient cells of Jurkat/A4 subline are resistant to drug-induced apoptosis. Exp Oncol 2001; 23:175-80 (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagy B, Ferrer A, Larramendy ML, Galimberti S, Aalto Y, Casas S, Vilpo J, Ruutu T, Vettenranta K, Franssilla K, et al.. Lymphotoxin beta expression is high in chronic lymphocytic leukemia but low in small lymphocytic lymphoma: a quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis. Haematologica 2003; 88:654-8; PMID:12801841 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons DL, Rowe M, Cope AP, Feldmann M, Brennan FM. Lymphotoxin acts as an autocrine growth factor for Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells and differentiated Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Eur J Immunol 1994; 24:1879-85; PMID:8056047; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.1830240825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daller B, Müsch W, Röhrl J, Tumanov AV, Nedospasov SA, Männel DN, Schneider-Brachert W, Helgans T. Lymphotoxin-β receptor activation by lymphotoxin-α(1)β(2) and LIGHT promotes tumor growth in an NFκB-dependent manner. Int J Cancer 2011; 128:1363-70; PMID:20473944; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.25456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta M, Gupta SK, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Gadd45a and Gadd45b protect hematopoietic cells from UV-induced apoptosis via distinct signaling pathways, including p38 activation and JNK inhibition. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:17552-8; PMID:16636063; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M600950200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libermann DA, Hoffman B. Gadd45 in the response of hepatopoietic cells to genotoxic stress. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2007; 39:329-35; PMID:17659913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casetti L, Martin-Lannerée S, Najjar I, Plo I, Augé S, Roy L, Chomel JC, Lauret E, Turhan AG, Dusanter-Fourt I. Differential contributions of STAT5A and STAT5B to stress protection and tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance of chronic leukemia stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res 2013; 73:2052-8; PMID:23400594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu MX. Roles of the stress-induced gene IEX-1 in regulation of cell death and oncogenesis. Apoptosis 2003; 8:11-8; PMID:12510147; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1021688600370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Gadd45 modulation of intrinsic and extrinsic stress responses in myeloid cells. J Cell Physiol 2009; 218:26-31; PMID:18780287; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.21582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gressot LV, Doucette TA, Yang Y, Fuller GN, Heimberger AB, Bögler O, Rao A, Latha K, Rao G. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b drives malignant progression in a PDGFB-dependent proneural glioma model by suppressing apoptosis. Int J Cancer 2015; 136:2047-54; PMID:25302990; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.29264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaymaz BT, Selvi N, Gokbulut AA, Aktan C, Gündüz C, Saydam G, Sahin F, Cetintaş VB, Baran Y, Kosova B. Suppression of STAT5A and STAT5B chronic myeloid leukemia cells via siRNA and antisense-oligonucleotide applications with the induction of apoptosis. Am J Blood Res 2013; 3:58-70; PMID:23358828 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim BH, Won C, Lee YH, Choi JS, Noh KH, Han S, Lee H, Lee CS, Lee DS, Ye SK, et al.. Sophoraflavanone G induces apoptosis of human cancer cells by targeting upstream signals of STATs. Biochem Pharmacol 2013; 86:950-9; PMID:23962443; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selvi N, Kaymaz BT, Gündüz C, Aktan C, Kiper HD, Sahin F, Cömert M, Selvi AF, Kosova B, Saydam G. Bortezomib induces apoptosis by interacting with JAK/STAT pathway in K562 leukemic cells. Tumour Biol 2014; 35:7861-70; PMID:24824872; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s13277-014-2048-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akilov OE, Wu MX, Ustyugova IV, Falo LD Jr, Geskin LJ. Resistance of Sézary cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis is mediated in part by a loss of THFR1 and a high level of the IER3 expression. Exp Dermatol 2012; 21:287-92; PMID:22417305; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01452.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Lee MK. Antiapoptotic property of human alpha-synuclein in neuronal cell lines is associated with the inhibition of caspase-3 but not caspase-9 activity. J Neurochem 2005; 93:1542-5; PMID:15935070; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He X, He L, Hannon GJ. The guardian's little helper: microRNAs in the p53 tumor suppressor network. Cancer Res 2007; 67:11099-101; PMID:18056431; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng J, Haas M. Frequent mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene in human leukemia T-cell lines. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10:5502-9; PMID:2144611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duffy MJ, Synnott NC, McGowan PM, Crown J, O'Connor D, Gallagher WM. p53 as a target for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40:1153-60; PMID:25455730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philchenkov A, Zavelevich M, Savinska L, Blokhin D. Jurkat/A4 cells with multidrug resistance exhibit reduced sensitivity to quercetin. Exp Oncol 2010; 32:76-80; PMID:20693966 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philchenkov AA, Zavelevich MP, Blokhin DYu. XIAP and Bcl-2 involvement in chemo- and radioresistance of Jurkat/A4 cells. Ukr Biokhim Zh 2009; 81 (4, Special Issue):237 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philchenkov AA, Shishko ED, Zavelevich MP, Kuiava LM, Miura K, Blokhin DY, Shton IO, Gamaleia NF. Photodynamic responsiveness of human leukemia Jurkat/A4 cells with multidrug resistant phenotype. Exp Oncol 2014; 36:241-5; PMID:25537217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strober W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr Protoc Immunol 2001; 21:3B:A.3B.1–A.3B.2; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/0471142735.ima03bs21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg CS, Craddock PR. Rapid single-step membrane protein assay. Clin Chem 1982; 28:1725-6; PMID:7083585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikhailov A, Sokolovskaya A, Yegutkin GG, Amdahl H, West A, Yagita H, Lahesmaa R, Thompson LF, Jalkanen S, Blokhin D, et al.. CD73 participates in cellular multiresistance program and protects against TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J Immunol 2008; 181:464-75; PMID:18566412; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 2008; 3:1101-8; PMID:18546601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.