Abstract

Introduction

Northern Ireland has high mental health needs and a rising suicide rate. Our area has suffered a 32% reduction of inpatient beds consistent with the national drive towards community based treatment. Taking these factors into account, a new Mental Health Crisis Service was developed incorporating a high fidelity Crisis Response Home Treatment Team (CRHTT), Acute Day Care facility and two inpatient wards. The aim was to provide alternatives to inpatient admission. The new service would facilitate transition between inpatient and community care while decreasing bed occupancy and increasing treatment in the community.

Methods

All services and processes were reviewed to assess deficiencies in current care. There was extensive consultation with internal and external stakeholders and process mapping using the COBRAs framework as a basis for the service improvement model. The project team set the service criteria and reviewed progress.

Results

In the original service model, the average inpatient occupancy rate was 106.6%, admission rate was 48 patients per month and total length of stay was 23.4 days. After introducing the inpatient consultant hospital model, the average occupancy rate decreased to 90%, admissions to 43 per month and total length of stay to 22 days. The results further decreased to 83% occupancy, 32 admissions per month and total length of stay 12 days after CRHTT initiation.

Discussion

The Crisis Service is still being evaluated but currently the model has provided safe alternatives to inpatient care. Involvement with patients, carers and all multidisciplinary teams is maximised to improve the quality and safety of care. Innovative ideas including structured weekly timetable and regular interface meetings have improved communication and allowed additional time for patient care.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Within mental health there have been radical shifts of service provision with a move of acute psychiatry away from inpatient care to the community. This links with the recommendations in the Bamford Review1 and Transforming your Care – Compton Report2.

Our team needed to introduce a new optimised service for people with mental health problems in our catchment area 24 hours a day, 7 days per week (24/7). Our aim was to provide alternatives to inpatient admission. There was over occupancy of acute psychiatric inpatient beds and this required change due to a move to a new unit with 30 beds compared to 44 (Figure 1). The NHS spends more on mental health than any other area of healthcare.3 In comparison to the UK average, mental health needs in Northern Ireland are 25% higher.4 At the time of establishing our new service, the suicide rate in Northern Ireland was increasing in contrast to England, Wales and Scotland.5

Fig 1.

Grangewood Crisis Service Unit

Our objectives were

To establish a 24/7 Mental Health Crisis Service incorporating inpatient beds, a high fidelity model Crisis Response Home Treatment Team (CRHTT) and Acute Day Care (ADC) facilities.

To develop a single point of co-ordinated access to secondary mental health services and thirdly to enhance safe alternatives to hospital admission. The communication across all interfaces was improved by the introduction of a Hospital Consultant model, Hospital Team and structured weekly timetable.

Incorporating the three elements of crisis care in one team is novel. The purpose of this paper is to describe aspects of this new service. We used ongoing audit and Plan, Do, Study,Act (PDSA) cycles to monitor the service development. We describe our findings.

Our previous service model

The Western Health and Social Care Trust provides care across five council areas in Northern Ireland. The Trust is divided into Northern and Southern sectors due to the large geographical area with two inpatient facilities. The Northern Sector inpatient unit previously had 5 Consultant Psychiatrists and Community Mental Health teams interfacing with the hospital, leading to 22+ ward rounds per week. There was no dedicated “hospital team.” Sector based teams were working independently, liaising and referring to other services when required.

The referral process to secondary care mental health services in a crisis was via General Practitioner (GP), Out of Hours General Practitioner (OOH GP) or Accident and Emergency Department. A psychiatrist or practitioner on call would assess the patient and determine the management plan, referring onto inpatient ward or other service as necessary. There was a Home Treatment Team 09.00-21.00 7 days per week and ADC service 09.00-17.00 5 days per week. Their main focus was providing additional resources and support to the community teams.

New service model

The new service model was a 24/7 Mental Health Crisis Service incorporating inpatient beds, CRHTT and ADC facilities. The CRHTT underakes crisis assessments, “gate- keeps” the inpatient beds and collaboratively establishes management plans.

The Crisis Resolution aspect of the team aims to enhance patient’s skills and improve future resilience. The functions of the CRHTT includes increasing support, short term prescribing of medications, frequent review until crisis abates and then timely discharge on completion. The Home Treatment aim is to replicate hospital care within the patient’s own home. During assessment of history and mental state, priority is given to management of risk and level of containment required. Physical examination, investigations,medication initiation and review, therapeutic intervention, monitoring of progress and carer support is provided.

ADC facility supports the assessment and management of patients within the Crisis Service. Inpatients and outpatients can be observed in a wide variety of settings. The service combines close monitoring with a less restrictive environment. Interventions including structured activity, psychoeducation, skills training and sign posting to community services are offered.

There is flexibility and a smooth transition when moving within different aspects of the Crisis Service. Step down from hospital supporting discharge and additional support and respite for carers can be facilitated. The service is multi- modal and multidisciplinary. The medical staff is consistent during the crisis period; inpatient, CRHTT and ADC phases.

EVIDENCE BASE

There are a range of heterogeneous mental health crisis services described in the literature. The evidence base for successful models is relatively sparse. When reviewing the evidence, we could not find any service with the same structure as our integrated inpatient, CRHTT and ADC model. Most of the literature considers separate ADC, CRHTT and assertive outreach teams as alternatives to inpatient admission. This heterogeneity has made it difficult to make comparison with our own model. There was no evidence base related specifically to Northern Ireland.

Some studies found a decrease in the number of hospital admissions in the months following crisis interventions ranging from 8-51%.6,7,8 Others found a reduction in admissions but increased bed occupancy or length of stay7,9 In contrast, there is some evidence that CRHTT has no impact on admission rates or length of stay.10,11 Several studies recommended combining crisis models to form integrated centres such as our model.12

METHODS

Review of current service and process to new Crisis Service

Inpatient services, community services and processes within were reviewed to identify any deficiencies in current care. The inconsistent approach towards admission and discharge of patients across five different mental health teams, was identified as a major issue.

Inpatient over-occupancy, multiple ward rounds and care planning meetings led to inefficiency. Nurses were unable to spend as much time engaging patients in therapeutic interventions as they wished. This led to development of a weekly timetable incorporating two ward round sessions.

Stake holders were identified including service users, carers, directorate, staff, specialist and non-specialist teams. There was an extensive consultation process with all teams. Other Trusts’ systems in Northern Ireland and the UK were reviewed. We considered what changes could improve services along with weaknesses to be eradicated.

Process mapping was used to chart the patient’s journey. The number of steps in the process, time frames and impact of bottle neck areas highlighted delays. Benefits and problems for patients and staff were outlined.

The COBRAs (Cost, Opportunity, Benefits, Risk, Analysis for satisfaction) framework was used as a basis for the service improvement model. This included situational analysis, assessing change required, scope of the service improvement, format and where it should start.

The Crisis Service operational policy set the service criteria. The standards for the new service were taken from the Royal College of Psychiatrists Occasional paper.13 The bed occupancy rate should be 85% or less and the ward size a maximum of 18 beds. The service development was reassessed initially weekly then fortnightly. There were regular meetings with community services to develop the service.

Introduction of new systems

The Crisis Service introduced new management structures, a medical staffing model and a structured weekly timetable. A Crisis Service manager, CRHTT and ADC manager and Inpatient manager were appointed. There are currently 2 Consultant Psychiatrists each with a middle grade / senior trainee and junior trainee covering two geographical sectors each.

The Crisis Service has a weekly interface meeting which all community mental health teams attend. Each patient is discussed and this then informs the management plan. Attendance allows important patient and risk assessment information to be shared throughout all involved teams.

Patients are categorised into a traffic light system. Red indicates acute status, amber for ongoing care and green for discharge planning. Red and green inpatients are reviewed at the main ward round and amber inpatients at the review ward round. Each Consultant has two inpatient ward round sessions per week (one main and one review). A ward round timetable is provided to all hospital and community teams enabling the keyworker to attend for their patient. CRHTT and ADC staff attend the ward rounds to enhance communication and facilitate early discharge.

The traffic light system extends into CRHTT and ADC encouraging consistency. A weekly ward round for patients in CRHTT and ADC assesses progress, allows changes to management plans and timing of medical review. The weekly timetable facilitates the multidisciplinary approach and allows more time to be spent on therapeutic interventions and staff training.

RESULTS OF ASSESSMENT / MEASUREMENT

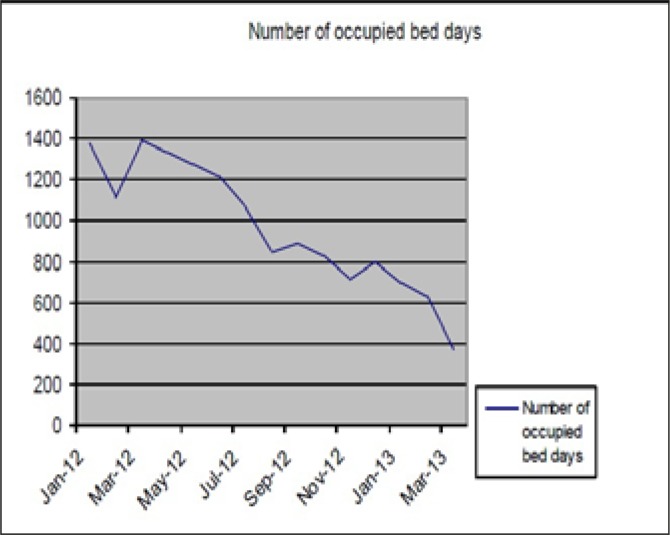

The data was collected on a monthly basis and evaluated from January 2012. Prior to the initial service change in May 2012, the average inpatient bed occupancy rate was 106.6% The average number of inpatient admissions was 48 per month. The average length of stay was 23.4 days. The number of occupied bed days taking into account number of beds available, number of available bed days and occupancy rate averaged 1298 per month during this period. (1/1/12-31/5/12)

After the deployment of dedicated Crisis Service Consultant Psychiatrists, the average occupancy rate decreased to 90%, number of admissions per month to 43.3, length of stay to 22 days and occupied bed days 1007. (1/6/12-30/9/12)

The introduction of a high fidelity CRHTT 9-5pm 5 days per week commenced on 1/10/2012. The bed occupancy rate average decreased to 82.7%, number of admissions to 32 per month, length of stay decreased to 12 days at this stage and occupied bed days to 779.3. (1/10/12-1/1/13)

The introduction of 24/7 CRHTT began on 07/01/2013. The averages for inpatient bed occupancy rate fell to 63%, admissions per month 35.6, length of stay at this time was 18 days and occupied bed days 563.3 (1/1/13-31/3/13).

Fig 2.

Graphical representation of the number of inpatient occupied bed days between January 2012 and March 2013.

481 assessments were performed by the new Crisis Service from 01/10/2012 to 31/03/2013. 177 assessments in first three months of CRHTT 9-5pm 5 days per week and 304 (63.2%) when performing assessments 24/7. This averaged 3.7 assessments per day since going 24/7. The outcomes of the assessments are shown in Table 1 below.

TABLE 1.

Outcome following Crisis Assessment by CRHTT

| Lead role in care | CRHTT/ADC | Inpatient | CMHT | GP | Addictions | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage (%) | 55.1 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 12.5 | 4 | 1.2 |

Feedback from patients and staff

Seven experience questionnaires in the inpatient unit were obtained from patients. The feedback was positive in all seven submitted with one commenting on the “huge advances.. made to the system as a whole” and that the “support received was tapered of (sic) very well and not ended abruptly.”

Staff focus groups were set up to encourage anonymised constructive critique. The feedback from these groups highlighted both positive and negative responses. A sample of the recorded quotes are as follows.

| “All that has led to better patient centred care for the patients from their admission right through to discharge” |

| “There are so many good positive aspects of it - compared to old when you had 5 ward rounds and 5 consultants and things could be very chaotic. All those things have improved for the better for patient centred care.” |

| “From a time factor point of view, with ward rounds going on every day, they had been going on until late afternoon. Now, they are focussed. They are time-scaled and there is time, extra time for nursing staff to prioritise their times with their own client groups.” |

| “There has been a lot of change for us, there’s been so much change in the past couple of years. There was a bit of resistance…But I think everybody has adapted really well and the change has been positive. You’d never want to go backwards now, this is far more productive.” |

DISCUSSION

Alternatives to inpatient care are the focus of government strategies with a shift from hospital to community care. Our objective was to establish a 24/7 Crisis Service which uniquely combined inpatient, CRHTT and ADC services. The results have shown improvement and an overall achievement of targets set. Presently, it is felt the achievements have justified this service transformation but the change hasn’t been without criticism.

The large scale of the project required a transition period and phased approach. This led to frequent changes within the system which could have been difficult to manage.

Simplifying the process for referral to mental health services in a crisis to a single point of access can improve accessibility, safety and quality. The aim is to strengthen patient and staff autonomy and links with the community. However, there could be a perceived lack of autonomy around the crisis service gatekeeping and this may have led to some staff feeling undervalued and their skills unrecognised.

The combination of inpatient, CRHTT and ADC into one team was innovative and led to improved consistency for patients and faster transition to the community. Average bed occupancy, number of admissions, length of stay and number of bed days all decreased with the initial change.

Further improvements in all outcomes were found with the initiation and extension of the CRHTT. Our results suggest that the introduction of a CRHTT has a positive impact although, direct comparison is difficult as no other service has integrated inpatient, CRHTT and ADC facilities.

Many of the patients (55.1%), who may have been previously admitted to an inpatient ward, were managed in the community but within acute care services. The majority of patients were initially managed within the Crisis Service (70.9%) This could suggest appropriate referrals to the service, a high acceptance rate or both.

A 24/7 service meant there was always an experienced professional to assess patients and establish a management plan. Previously, assessment was by a junior trainee doctor, telephone consultation or direct admission. Concerns have been raised by the Royal College about trainees losing acute assessment experience. Trainees could attend assessments with CRHTT professionals to develop their skills in this area.

Of note, there is currently no dedicated psychologist or pharmacist. These could be viewed as major gaps in the multidisciplinary team.

At the interface meeting, all teams are present improving communication. The time required for staff to attend Crisis Service meetings and ward rounds is acknowledged and teleconferencing may be helpful in the future.

Patients referred and their families can make informed choices with staff about their options in a crisis when safe to do so. They may be discharged earlier from inpatient care providing more of a “recovery approach” to their care. This moves away from paternalistic management.

The most complex issue encountered is the culture change required. Changed processes, boundaries, relationships and interfaces have been encountered. Potential negatives have been considered, such as staff ‘burn out’ and deskilling due to subspecialisation. Ideas to counteract problems have included rotation within posts, additional training and increased supervision.

We will continue to review the objective outcome measures but also plan to evaluate subjective measures such as satisfaction surveys, patient questionnaires and data from focus groups. Longer term adverse outcomes such as serious adverse incidents, untoward incidents and patient suicides should be looked at to ensure patient safety. Staffing measures such as sickness levels, transfer requests and staff complaints could provide more information on the impact on staff.

Overall, since implementing the new Crisis Service the standards set by the Royal College of Psychiatrists have been met. There is an appropriate inpatient occupancy rate with a large proportion of care being provided in the community. The inpatient occupancy rate, total number of admissions and total length of stay have all decreased. Patients benefit from increased personal time with staff and consistent meetings with the multidisciplinary team. We recommend this model to those wishing to consider alternatives to inpatient management.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the staff involved in the development of the Crisis Service and providing the information for this paper. This includes Crisis Service staff, community teams and senior management.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bamford D, McClelland R. A comprehensive legislative framework. Belfast: DHSSPSNI; 2007. The Bamford review of mental health and learning disability (Northern Ireland) Available from: http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/legal-issue-comprehensive-framework.pdf. Last accessed November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Transforming your care. A review of health and social care in Northern Ireland. Belfast: DHSSPSNI; 2011. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/transforming-your-care-review-of-hsc-ni-final-report.pdf. Last accessed November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The National Audit Office. London: The Stationary Office; 2007. Helping people through mental health crisis: the role of crisis resolution and home treatment services.Report by the controller and auditor general. HC 5 session 2007-2008. Available online from: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2007/12/07085.pdf. Last accessed November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Promoting mental health. Strategy and action plan 2003-2008. Belfast: DHSSPSNI; 2003. Available from: http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/menhealth.pdf. Last accessed November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The National Confidential Inquiry into suicide and homicide by people with mental illness. Annual report: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, July 2012. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2012. Available from: http://www.bbmh.manchester.ac.uk/cmhr/research/centreforsuicideprevention/nci/reports/annual_report_2012.pdf. Last accessed November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjolie H, Karlsson B, Kim HS. Crisis resolution and home treatment: structure, process and outcome – a literature review. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nurs. 2010;17(10):881–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy S, Irving CB, Adams CE, Driver R. Crisis intervention for people with severe mental illnesses. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):676–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson S, Nolan F, Hoult J, White IR, Bebbington P, Sandor A, et al. Outcomes of crises before and after introduction of a crisis resolution team. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:68–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs R, Barrenho E. Impact of crisis resolution and home treatment teams on psychiatric admissions in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):71–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.079830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathod S, Lloyd A, Asher C, Baird J, Mateus E, Cyhlarova E, et al. Lessons from an evaluation of major change in adult mental health services: effects on quality. J Ment Health. 2014;23(5):271–5. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.951487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adesanya A. Impact of a crisis assessment and treatment service on admissions into an acute psychiatric unit. Australas Psychiatry. 2005;13(2):135. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vázquez-Bourgon J, Salvador-Carulla L, Vázquez-Barquero JL. Community alternatives to acute inpatient care for severe psychiatric patients. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2012;40(6):323–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royal College Psychiatrists. Ten standards for adult in-patient mental healthcare. Occasional Paper OP79. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2011. Do the right thing: how to judge a good ward. Available from: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/OP79_forweb.pdf. Last accessed November 2015. [Google Scholar]