Abstract

We present a case of a 62‐year‐old diabetic woman with acute pyelonephritis and spondylitis caused by Salmonella typhi. She was admitted to Tokyo Medical Dental University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, because of unconsciousness and was diagnosed with sepsis by retrograde pyelonephritis as a result of Salmonella typhi. Antibiotics treatment was immediately started; however, she subsequently developed lumbar spondylitis, and long‐term conservative treatment with antibiotics and a fixing device were required. This is the first report of a diabetic patient who developed retrograde urinary tract infection with Salmonella typhi, followed by sepsis and spondylitis. The infection could be a result of diabetic neuropathy, presenting neurogenic bladder and hydronephrosis. The patient was successfully treated with antibiotics and became asymptomatic with normal inflammatory marker levels, and no clinical sign of recurrence was observed in the kidney and spine at 4 months.

Keywords: Diabetic neuropathy, Retrograde pyelonephritis, Salmonella typhi

Introduction

Salmonella typhi is a rare cause of urinary tract infection and spondylitis, especially in non‐endemic areas1. We herein report a unique case of retrograde pyelonephritis of Salmonella typhi as a result of neurogenic bladder caused by diabetic neuropathy, followed by sepsis and spondylitis without typical typhoid fever.

Case report

A 62‐year‐old woman, with no history of typhoid fever and gastrointestinal symptoms, was admitted to Tokyo Medical Dental University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, because of unconsciousness. Two months before admission, she experienced frequent urination, thirst and back pain, while her bodyweight had reduced by 12 kg. She had no history of travelling in endemic areas of Salmonella typhi before admission. She had no contact with any persons diagnosed with the microorganism.

On admission, her blood pressure, pulse rate and body temperature were 125/78 mmHg, 71 b.p.m. and 35.6°C, respectively. Table 1 shows laboratory data. Her blood glucose concentration was 845 mg/dL, with glycated hemoglobin being 11.5%. She was diagnosed with diabetes. White blood count (WBC) and C‐reactive protein (CRP) levels were 21,600/μL and 22.5 mg/dL, respectively. Her serum creatinine was 1.25 mg/dL. Urinalysis showed bacteriuria with many WBC casts. She exhibited orthostatic hypotension, reduced ankle reflexes and abnormally decreased vibration perception to a 128‐Hz tuning fork, and post‐voiding residual urinary volume in the bladder was more than 500 mL, suggesting diabetic peripheral and autonomic neuropathy. Salmonella typhi was isolated from both the blood and urine, but not from fecal cultures, although we examined fecal culture twice. Abdominal computed tomography showed hydronephrosis, enlargement and perinephric stranding of the right kidney; however, neither urolithiasis, a common cause of hydronephrosis as a result of Salmonella typhi, nor destruction of lumbar spine, which causes neurogenic bladder, were observed (Figure 1). In addition, neither cholelithiasis nor an abnormality in the biliary tract system were found in the images. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed as acute retrograde pyelonephritis and sepsis as a result of Salmonella typhi infection. Diabetic neurogenic bladder was likely to contribute to the infection. The antibiotics sensitive to this microorganism involved third‐generation cephalosporin, carbapenem and quinolone, and because of the complicated sepsis, the patient was initially treated with meropenem immediately after admission, and maintained the regimen even after Salmonella typhi was detected in urinary cultures.

Table 1.

Laboratory data at admission

| Complete blood count | Urinalysis | Blood gas analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | 21,600/μL | pH | 5.5 | pH | 7.494 |

| Red blood cells | 485 × 104/μL | Occult blood | (3+) | PaO2 | 75.1 |

| Hemoglobin | 14.1 g/dL | Glucose | (–) | PaCO2 | 38.6 |

| Hematocrit | 41.2% | Protein | (2+) | HCO3 − | 29.4 |

| Platelet | 17.2 × 104/μL | Ketone | (–) | Base excess | 6.2 |

| White blood cells | 50–99/HPF | ||||

| Blood chemistry | |||||

| Albumin | 2.2 mg/dL | AST | 45 IU/L | Glucose | 845 mg/dL |

| BUN | 75 mg/dL | ALT | 39 IU/L | HbA1c | 11.5% |

| Creatinine | 1.25 mg/dL | Total bilirubin | 0.7 mg/dL | C‐reactive protein | 22.53 mg/dL |

| Na | 140 mEq/L | γ‐GTP | 57 IU/L | ||

| K | 3.7 mEq/L | CK | 52 IU/L | ||

| Cl | 97 mEq/L | Amylase | 56 IU/L | ||

γ‐GTP, gamma‐glutamyl transpeptidase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CK, creatine kinase; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography on admission.

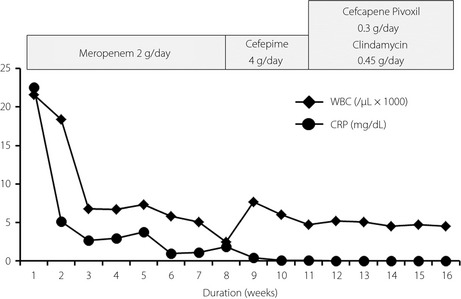

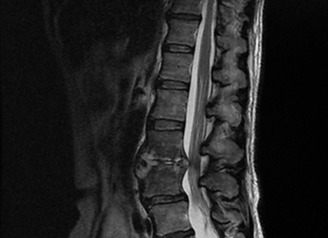

Antibiotics were immediately given, and strict glycemic control was able to be achieved by multiple daily injection of insulin with a total dosage of 15 units per day, resulting in robust decreases in WBC and CRP levels (Figure 2); however, the patient's back pain and low‐grade fever still remained at 4 weeks after admission. In order to investigate the infection focuses other than the right kidney, abdominal computed tomography, cardiac ultrasonography and lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were carried out. Destruction of the L3 and L4 vertebrae (Figure 3) was observed by lumbar MRI, suggesting that lumbar spondylitis occurred as a result of the hematogenous spread of Salmonella typhi. Without biopsy of the infected lumber spine, antibiotics treatment and rest were continued, because the patient did not complain of neurogenic symptoms. There was no fluid retention near the lumbar spine. Inflammatory signs and symptoms disappeared after a 7‐week antibiotics treatment. Meropenem was replaced by cefepime at 8 weeks because of the subsequent leukopenia. She showed a significant improvement of WBC and CRP levels, and eventually cefepime was changed to oral antibiotics (Figure 2). The patient became asymptomatic with normal inflammatory marker levels, and no clinical signs of recurrence in the kidney and spine at 4 months (Figure 2). We re‐studied lumbar MRI 12 weeks after administration of antibiotics, and found that the signal intensity in the T2‐weighted image in the infection sites was reduced.

Figure 2.

Clinical course.

Figure 3.

Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging at 1 month after admission.

Discussion

Salmonella typhi is known to cause typhoid fever, with gastroenteric symptoms, such as vomiting, diarrhea, low‐grade fever and rose spots2. Its infection is common in underdeveloped countries, where sanitation is poor, and where there is fecal contamination of food and water. It is sometimes observed in those who live in non‐endemic areas with a recent history of travelling in endemic areas. The present case is unique in that: (i) retrograde urinary tract infection (pyelonephritis) of Salmonella typhi occurred in a non‐endemic country, Japan, without known sources of Salmonella infection; (ii) it could be a result of diabetic neuropathy, presenting neurogenic bladder and hydronephrosis of the right kidney; (iii) the patient had no prodromal bowel symptoms associated with typhoid fever; and (iv) the patient showed a spread of Salmonella typhi infection to the lumbar spine. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of a retrograde infection of Salmonella typhi in the urinary tract system in a patient with diabetic neurogenic bladder, leading to sepsis and lumbar spondylitis.

Neurogenic bladder is one of the serious complications associated with diabetic autonomic neuropathy, leading to life‐threatening conditions such as acute pyelonephritis and sepsis3. Those who have neurogenic bladder complain of diminished filling sensation of the bladder and its poor contractility, resulting in increased post‐voiding residual urinary volume. This condition is exclusively high risk at urinary tract infection including pyelonephritis, lithiasis and thus renal dysfunction. A previous study showed that Escherichia coli is the most common microorganism in elderly diabetic patients with acute pyelonephritis, followed by Candida species and Gram‐positive cocci 4. In the present case, we detected Salmonella typhi from the urine and blood cultures of a type 2 diabetic patient who might have had a long duration of diabetes with severe autonomic neuropathy. Urinary tract infection with Salmonella typhi is reported in less than 1% of total cases, although the worldwide prevalence of the infection has been estimated to be 12–33 million cases per year1. A previous review summarized the clinical manifestation of 18 patients with Salmonella typhi bacteriuria, and found that urolithiasis, bladder abnormality and kidney diseases are often associated with urinary tract infection with Salmonella typhi; however, the complication of diabetes has not been reported in the literature5. Thus, the presence of diabetic neuropathy, such as neurogenic bladder, should be evaluated carefully, when diabetic patients are diagnosed with urinary tract infection by Salmonella typhi.

Other than pyelonephritis, iliopsoas muscle abscess and spondylitis could cause back pain in diabetic patients6, 7. In the present case, spondylitis of the lumbar spine was identified by lumbar MRI. Lumbar vertebrae are the site of predilection for spondylitis, and a hematogenous spread is reported to be a principal route of the infection8. Spondylitis sometimes occurs after abdominal or spinal surgery or myelography9. The patient had never received surgery or myelography; thus, spondylitis appeared to be caused by a hematogenous spread of Salmonella typhi from the right kidney. Salmonella typhi infection of the bone and joint is extremely rare, as well as that of the urinary tract system1. Treatment of spondylitis primarily includes intravenous administration of antibiotics and rest using a fixing band. Surgery might be required in patients when antibiotics are not effective or when patients develop complications, such as neurological deficits. Ceftriaxone or fluoroquinolones are likely to be used for the treatment of Salmonella typhi 10. There was no clinical evidence of neurological deficits, fluid collection and deformity of the lumbar spine in the infection sites.

In conclusion, neurogenic bladder as a result of diabetic autonomic neuropathy could cause hydronephrosis, leading to retrograde urinary tract infection with Salmonella typhi, followed by sepsis and lumbar spondylitis.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

J Diabetes Investig 2016; 7: 436–439

References

- 1. Huang DB, DuPont HL. Problem pathogens: extra‐intestinal complications of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5: 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Christopher M, Parry MB, Tran Tinh Hien MD, et al Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1770–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vinik AI, Maser RE, Mitchell BD, et al Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1553–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kofteridis DP, Papadimitraki E, Mantadakis E, et al Effect of diabetes mellitus on the clinical and microbiological features of hospitalized elderly patients with acute pyelonephritis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57: 2125–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathai E, John TJ, Rani M, et al Significance of Salmonella typhi bacteriuria. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33: 1791–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fernández‐Ruiz M, Estébanez‐Muñoz M, López‐Medrano F, et al Iliopsoas abscess: therapeutic approach and outcome in a series of 35 patients. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2012; 30: 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabih O, Darouiche MD. Spinal Epidural Abscess. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2012–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller ME, Fogel GR, Dunham WK. Salmonella spondylitis. A review and report of two immunologically normal patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70: 463–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ortiz‐Neu C, Marr JS, Cherubin CE, et al Bone and joint infections due to Salmonella. J Infect Dis 1978; 138: 820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Francis A, Waldvogel MD, Medoff G, et al Osteomyelitis: a review of clinical features, therapeutic considerations and unusual aspects. N Engl J Med 1970; 282: 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]