Abstract

Hemangioma of the heart presenting as a primary cardiac tumor is extremely rare, accounting for approximately 2% of all primary resected heart tumors. Only a few cases of cardiac hemangiomas have been reported to arise from the left atrial wall. In this case report we share our experience in the diagnosis and surgical resection of a large (9 × 7 cm) left atrial hemangioma and reconstruction of the heart using porcine urinary bladder membrane.

Keywords: cardiac tumor, left atrium, hemangioma, Acell, MatriStem Surgical Matrix

Introduction

Cardiac primary tumors are not common, and they are often diagnosed postmortem because they are frequently asymptomatic. The incidence of primary cardiac tumors distinguished at autopsy is about 0.02%. Three-quarters of cardiac tumors can be categorized as benign tumors on histology. Myxoma is the most common among cardiac tumors.1 Hemangioma generally arises from the gastrointestinal tract or the cutaneous structures and is an extremely rare heart tumor. Cavernous hemangioma is one of the three histological types of cardiac hemangiomas, with the others being capillary type and mixed.2 In this case report we share our experience in the diagnosis and resection of a cavernous cardiac hemangioma as well as reconstruction of the heart using the MatriStem® Surgical Matrix PSMX porcine urinary bladder membrane (ACell, Inc., Columbia, MD).

Case Report

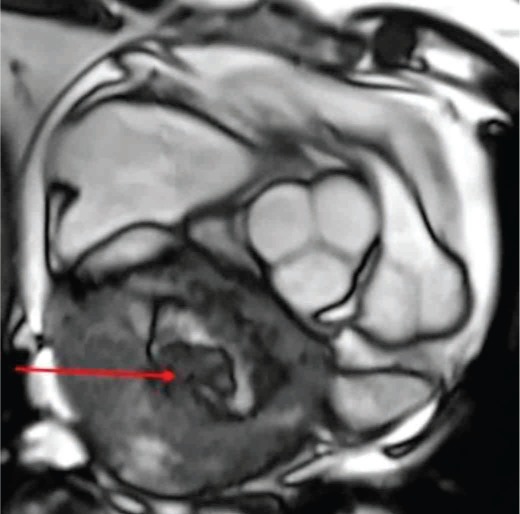

The patient was a 67-year-old woman who presented with exertional dyspnea and palpitations during the past several months. An ECG was normal at her primary care physician office, and her symptoms were attributed to some deconditioning. She had a normal stress test within the last 2 years and had never smoked. Her symptoms had progressively worsened with time, with decreased exercise tolerance. During a follow-up visit, she was found to have an irregular heartbeat and was directed to the emergency department, where she was found to be in atrial fibrillation. She underwent computed tomography (CT) angiography of the lungs to rule out pulmonary embolus and was found to have a left atrial mass. The patient denied any orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or chest pain. The plan was to start the patient on beta blockers to maintain sinus rhythm and to start her on aspirin. Meanwhile, the patient underwent a cardiac echocardiogram followed by a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) (Figure 1). The echocardiogram showed a huge tumor measuring 9.5 × 7.5 × 6.0 cm in the left cardiac cavity that was compressing the left atrium and causing moderate mitral regurgitation.

Figure 1.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) showing a large, heterogeneous left atrial mass (8.7 × 8.0 × 7.7 cm).

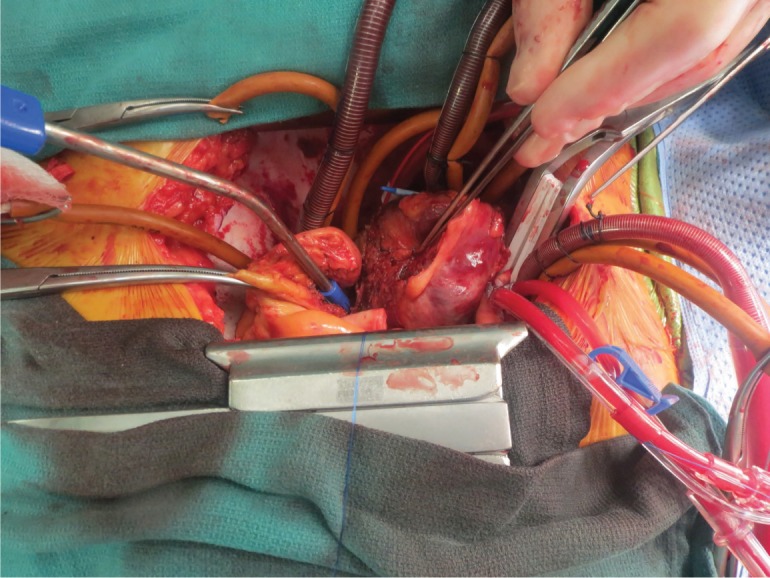

A consensus was reached during the multidisciplinary cardiac tumor board to proceed with resection of the tumor and reconstruction of the heart using ACell membrane. Coronary angiography was performed to exclude obstructive coronary artery disease before cardiac surgery, and it showed normal coronary arteries and delayed vascular blush—indicating a vascular tumor that fed from the left circumflex artery. The operation, performed via median sternotomy, was done on an IRB approved protocol with the patient giving full consent. The superior and inferior vena cava were directly cannulated and the displaced aorta was cannulated in the standard fashion. The patient was placed on full cardiopulmonary bypass with both vena caval tapes snared. The superior vena cava was divided just above the right atrium, and the ascending aorta was divided just beyond the sinotubular junction. This allowed exposure of the tumor, which could then be dissected free of the right pulmonary artery and the main pulmonary artery as well as off the vena cava. Once the heart was fully mobilized, the left atrium was opened and the tumor could be seen arising from the roof and encompassing the entire left atrium (Figure 2). The mass was excised with the roof and posterior left atrium all the way to the left and right pulmonary veins (Figure 3). The defect was then reconstructed with an acellular extracellular matrix membrane derived from porcine urinary bladder (ACell MatriStem Surgical Matrix). The patch was sewn to the left atrium using a running 4-0 prolene suture. The patient was successfully weaned off bypass, her sternum was closed, and she was transferred into a secure unit. After recovering from surgery, the patient was transferred to the regular surgical floor and was soon discharged.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative image of the hemangioma arising from the roof and encompassing the entire left atrium.

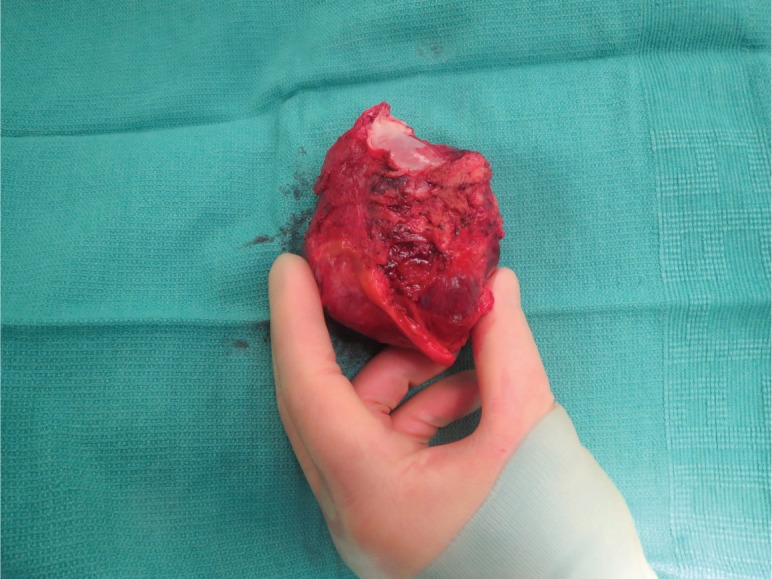

Figure 3.

The excised left atrial hemangioma (9.5 × 7.5 × 6.0 cm).

Discussion

Dyspnea, arrhythmias, atypical chest pain, pericardial effusion, congestive heart failure, ventricular outflow tract obstruction, embolic events, or sudden cardiac death may be features of the cardiac hemangioma; however, it is commonly asymptomatic.3

Echocardiography is the best diagnostic imaging modality to suitably screen for cardiac tumors, including cardiac hemangiomas.2 Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are complementary methods in the diagnostic workup to assess the scope of myocardial and local invasion. Coronary angiography will typically be an essential part of the preoperative evaluation to exclude obstructive coronary artery disease. The natural history of cardiac hemangioma is changeable: it can continue to proliferate, cease growing, or regress.2,4 Complete tumor excision is suggested for tissue diagnosis and impending cure, with a likely good long-term prognosis. The rate of recurrence after surgical resection is indefinite.5 A variety of surgical approaches have been suggested. Median sternotomy with cardiopulmonary bypass is generally necessary for intracardiac tumors, whereas right-sided tumors can be approached by a right atriotomy. For left ventricular (LV) tumors, a left ventriculotomy is the best way to avoid postoperative LV dysfunction and arrhythmia.6

Traditionally, reconstruction of atrial tissue has been accomplished by using bovine pericardium patches, and we have used this in our practice for reconstruction of the right and left atriums.7 However, we have started using the ACell membrane for the potential benefit of remodeling the cardiac tissue. Porcine urinary bladders and other extracellular matrix scaffolds have been shown in several studies to be a promising material to promote tissue growth while providing strong structural support.8 Another benefit of this novel acellular patch is the presence of a basement membrane that may lead to more durability and longevity of the atrial reconstruction. In addition, we did not encounter any technical difficulty sewing the patch to the native atrial tissue, and it was also noted to be hemostatic after the patient had been weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass and given protamine.

As part of our assessment of the MatriStem Surgical Matrix for cardiac reconstruction, we performed a follow-up imaging study that included a CT scan of the chest performed 6 months after resection and reconstruction. There has been no evidence of any breakdown or loss of integrity of the atrial wall and no recurrence of the tumor. As we continue to use the MatriStem Surgical Matrix, there will be an ongoing need for repeat imaging studies at 6-month intervals (up to 2 years) to assess the integrity of the membrane.

Conclusion

Cardiac hemangioma is a rare occurrence. This case highlights the role of echocardiography as an acceptable imaging modality for detecting cardiac tumors including cardiac hemangioma. In addition, median sternotomy was the approach of choice in our case because of the tumor's inaccessibility and posterior location. We were able to achieve good results by using the MatriStem extracellular matrix membrane to reconstruct the right atrial defect following tumor resection. A short-term follow-up imaging study showed integrity of the reconstruction, and additional imaging studies are planned. Our early results with the MatriStem Surgical Matrix are particularly encouraging, and long-term outcomes using this membrane are currently being investigated.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The author has completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

References

- 1.Strauss R, Merliss R. Primary tumors of the heart. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1945;39:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eftychiou C, Antoniades L. Cardiac hemangioma in the left ventricle and brief review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009 Jul;10(7):565–7. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32832cafc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas JE, Eror AT, Kenney M, Caravalho J., Jr. Asymptomatic right atrial cavernous hemangioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2004 Nov–Dec;13(6):341–4. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vakili H, Khaheshi I, Foroughi M, Ghaderi H, Esmaeeli S, Jafari M. Cardiac Hemangioma of RVOT in a Patient with Atypical Chest Pain. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:285479. doi: 10.1155/2014/285479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brizard C, Latremouille C, Jebara VA et al. Cardiac hemangiomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993 Aug;56(2):390–4. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)91193-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oueida FM, Lui RC, Al-Refae MA, Al-Omran HM. Left ventricular hemangioma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2014 Jan;22(1):77–9. doi: 10.1177/0218492312463709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MP, Correa AM, Blackmon S et al. Outcomes after right-side heart sarcoma resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011 Mar;91(3):770–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Deng L, Wang Y, Ge L, Chen Y, Liang Z. Porcine urinary bladder matrix-polypropylene mesh: a novel scaffold material reduces immunorejection in rat pelvic surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Sep;23(9):1271–8. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]