Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prevalence and natural course of pulmonary cysts in a population-based cohort and to describe the CT image characteristics in association with participant demographics and pulmonary functions.

Materials and Methods

Chest CT scans of 2633 participants (mean 59.2 years; 50% female) of the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) were visually evaluated for the presence of pulmonary cysts and their image characteristics. These findings were correlated with participant demographics and results of pulmonary function tests as well as the presence of emphysema independently detected on CT. The interval change was investigated by comparison with previous CT scans (median interval, 6.1 years).

Results

Pulmonary cysts were seen in 7.6% (95% CI, 6.6-8.7; 200/2633). They were not observed in participants younger than 40 years old, and the prevalence increased with age. Multiple cysts (≥5) were seen in 0.9% of all participants. Participants with pulmonary cysts showed significantly lower BMI (P<0.001). Pulmonary cysts were most likely to appear solitary in the peripheral area of the lower lobes and remain unchanged or slightly increase in size over time. Pulmonary cysts showed no significant influence on pulmonary functions (P=0.07-0.6) except for DLCO (P=0.03) and no association with cigarette smoking (P=0.1-0.9) or emphysema (P=0.7).

Conclusions

Pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT may be a part of the aging changes of the lungs, occurring in asymptomatic individuals older than 40 years, and are associated with decreased BMI and DLCO. Multiple pulmonary cysts may need to be evaluated for the possibility of cystic lung diseases.

Keywords: CT, Lung, Cysts, the Framingham Heart Study

Introduction

A pulmonary cyst is defined as a round, usually thin-walled, parenchymal lucency or low-attenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung on chest CT [1]. Incidental findings of pulmonary cysts are becoming more common because of the widespread use of CT scans in daily clinical practice and in lung cancer screening. Multiple pulmonary cysts are identified in various diseases such as pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) [2]. These progressive diseases are often symptomatic and may result in impairment of pulmonary functions. In contrast, solitary or sporadic pulmonary cysts can be incidentally seen on chest CT of otherwise healthy individuals. In a study by Copley et al, pulmonary cysts were seen on CT in 25% (10/40) of individuals older than 75 years but in no individuals younger than 55 years (0/16) [3]. More recently, Winter et al also reported pulmonary cysts were seen in 13% (6/47) of individuals older than 65 years but none in those aged 30 to 50 years (0/24) [4]. These studies suggest that asymptomatic pulmonary cysts could be a part of the aging processes. Other age-related findings of the lung were reticular pattern, fibrotic changes, bronchial wall thickening, and air trapping [3-8]. It is important to differentiate asymptomatic pulmonary cysts from progressive cystic lung diseases or emphysema. However, there is no systematic study that has investigated the clinical impact of pulmonary cysts in a large cohort. There is a clear gap in knowledge in the prevalence and management of pulmonary cysts. We hypothesize that most of incidentally-found pulmonary cysts could be regarded as a part of the aging changes.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the prevalence and natural course of pulmonary cysts in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) cohorts and to describe their CT imaging characteristics in association with participant demographics and pulmonary functions, which may help clinically, manage pulmonary cysts found on chest CT.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The original cohort of the FHS was recruited in 1948 [9]. Subsequently, the Offspring cohort, which consists of children of the original cohort members and their spouses, was recruited in 1971, followed by the Third Generation cohort in 2002, consisting of the grandchildren of the original cohort members. From 2009 to 2011, 2764 participants of the Offspring and the Third Generation cohorts underwent a non-contrast chest CT scan (FHS-MDCT2) in the supine position at full inspiration using a 64-detector-row scanner (Discovery, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with 120 kV, 300-350 mA, gantry rotation time of 0.35 second, and section thickness of 0.63 mm. Of those, 131 were missing CT image data. Therefore, 2633 participants (mean age, 59.2 years; SD, 12.0; range, 34-92 years; 50% female) who had chest CT scans were included. From 2002 to 2005, many of those participants previously underwent an ECG-gated non-contrast cardiac CT scan (FHS-MDCT1) using an 8-detector-row scanner (Lightspeed, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with 120 kV, 320-400 mA, a gantry rotation time of 0.5 seconds, and section thickness of 2.5 mm. The coverage of the scan is from 2 cm below the carina to the apex of the heart. The institutional review boards at both Brigham and Women's Hospital and Boston University approved the present study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants upon the enrollment of the FHS.

Evaluation of Chest CT images

Chest CT scans (MDCT2) of 2633 participants were evaluated on a workstation (Virtual Place Raijin, AZE Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for pulmonary cysts with a fixed lung window setting (WL=-700, WW=1500). Pulmonary cysts are defined as a round, thin-walled parenchymal lucency or low-attenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung [1] (Figure 1). The evaluation process was divided into two phases: 1) detection of pulmonary cysts, and 2) characterization and measurement.

Figure 1.

A transaxial CT image of a 60-year-old female who is a former smoker with 4.2 pack-years shows a solitary cyst in the right lower lobe of the lungs. The cyst is circumscribed with a thin wall and measures 17 mm in diameter.

First, CT scans were reviewed for the presence of pulmonary cysts (0: absent, 1: present) by three board-certified radiologists (TA, HH, MN) using a modified sequential reading method as previously described [10, 11]. Reader 1 reviewed all CT scans for screening of pulmonary cysts, providing a score of 0 or 1 for each case. Reader 1 repeated the review of cases scored 0 in the first review; two sets of scores were combined to increase the sensitivity. After the evaluations by Reader 1, cases with score 1 and approximately 20% of those with the score 0 were forwarded to another review by Reader 2. Finally, Reader 3 reviewed discordant cases between first and second readers. Final scores were determined with the majority opinion of all three readers [10, 11].

Second, cases identified with pulmonary cysts were reviewed by consensus of Readers 1 and 2 for the following image features: 1) number of cysts (Solitary=1, Sporadic=2-4, Multiple≥5); 2) lobe of the lung (upper, middle and lingular, or lower); 3) location within the lobe (central, peripheral, subpleural); 4) image findings of the cyst (calcification, penetration of blood vessels, fluid accumulation). The longest diameter of the pulmonary cyst was measured using a caliper-type measurement tool by Reader 1. Although most of the cases had a solitary cyst, if participants had more than one cyst in the lungs, the largest and most distinct cyst was regarded as representative of the case and evaluated for the imaging features and measurements. In addition, the presence of emphysema on chest CT scans was provided from a previous study (Unpublished data) [11]. In brief, chest CT scans were evaluated in three lung sections (upper, middle, lower) for the presence of emphysema using the modified sequential reading method in the same manner as the evaluation for pulmonary cysts.

The demographics of participants, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status with pack-years, and the results of pulmonary function tests (FEV1, FVC, DLCO, TLC) were obtained from the exams closest to the date of chest CT scan and were compared based on the result of the qualitative and quantitative evaluations of pulmonary cysts.

Prior cardiac CT scans (MDCT1, median 6.1 years prior, ranging 4.0 to 8.4 years) were reviewed for comparison when available. Interval increase or decrease in size of the cyst was determined by changes in diameter of more than 2 mm, accounting for a possible variability based on the results of the preliminary study described as follows [12]. Two radiologists (TA, HH) performed measurements of the cysts in 50 cases randomly selected from those with pulmonary cysts detected in the first phase of the evaluation. The first reader made the measurement twice separated by more than six months and the second reader did once.

Statistical analysis

Interobserver agreement of visual evaluation of pulmonary cysts was indicated with κ values calculated using MedCalc (version 14.8.1, MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) [13]. Intra- and interobserver measurement variability in the diameter of pulmonary cysts were evaluated with concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) and Bland-Altman plots with mean and 95% limits of absolute difference of diameter, calculated or created also using MedCalc [14].

All the other statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.1.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Participant demographics were investigated using mixed effect models for quantitative variables (age, BMI, pack-years, and coronary artery calcium scores) and generalized estimating equations for categorical variables (sex, smoking status, respiratory symptoms) to account for familial correlations in the cohorts [15]. All the results for the demographics, including BMI, smoking status, pack-years, coronary artery calcium scores and respiratory symptoms were adjusted for age and sex. In addition, the result for coronary artery calcium scores was adjusted for the presence of emphysema; the results for respiratory symptoms were adjusted for smoking status and pack-years. The results of pulmonary function tests were compared between those with and without pulmonary cysts with adjustments for age, smoking status, and pack-years. The associations between the presence of pulmonary cysts and emphysema, and between the image finding of vascular penetration and emphysema were evaluated with the Pearson Chi-square test. P values were from two-sided tests and regarded as statistically significant at the level of 0.05.

Results

Of 2633 participants, 200 (7.6%; 95% CI, 6.6-8.7%) were identified with at least one pulmonary cyst on chest CT scans. Interreader agreement regarding the presence of pulmonary cysts between the first and second readers was substantial (κ =0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.81). In the cases with score 0 provided by the first reader and subsequently reviewed by the second reader, the agreement rate between first and second readers was 98.4%. Image characteristics of pulmonary cysts are summarized in Table 1. 64% of pulmonary cysts (128/200) were solitary, 65.5% (131/200) were in the lower lobe of the lungs, and 59.5% (119/200) were located in the peripheral area. Vascular penetration was seen in 10% (20/200); of these, only 4 cases were accompanied with emphysema. There was no significant association between the specific finding of vascular penetration and emphysema (P=0.61). Calcification was seen in only one case (0.5%). No pulmonary cysts appeared with a fluid collection.

Table 1. Image characteristics of pulmonary cysts.

| Frequency | Percent in participants with pulmonary cysts (N=200) | Percent in all participants (N= =2633) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cysts | |||

| Solitary (1) | 128 | 64% | 4.9% |

| Sporadic (2-4) | 49 | 24.5% | 1.9% |

| Multiple (≥5) | 23 | 11.5% | 0.9% |

| Lobe of the lungs | |||

| Lower | 131 | 65.5% | 5% |

| Upper | 44 | 22% | 1.7% |

| Middle and lingular | 25 | 12.5% | 1% |

| Location in the lobe | |||

| Peripheral | 119 | 59.5% | 4.5% |

| Subpleural | 62 | 31% | 2.4% |

| Central | 19 | 9.5% | 0.7% |

| Calcification | |||

| Absent | 199 | 99.5% | 7.6% |

| Present | 1 | 0.5% | 0.04% |

| Vascular penetration | |||

| Absent | 180 | 90% | 6.8% |

| Present | 20 | 10% | 0.8% |

Participant demographics in association with pulmonary cysts are summarized in Table 2. Mean age of participants with pulmonary cysts was 63.0 years, significantly higher than those without pulmonary cysts (58.9 years, P<0.001). BMI of participants with pulmonary cysts (27.1) was significantly lower than those without pulmonary cysts (28.6, P<0.001). There were no significant differences in smoking status (P=0.1-0.7) and pack-years (P=0.9). Means of coronary artery calcium scores were significantly different between the two groups (P= =0.006), but the score tended to be lower in participants with pulmonary cysts than in those without pulmonary cysts. There was a trend towards fewer reports of respiratory symptoms in those with pulmonary cysts, but the results were not significant (P=0.8, 0.051). Participants with pulmonary cysts were further stratified with smoking status (Table 3). There were no significant difference between non-smokers and smokers in demographic features (age, sex, BMI), coronary artery calcium score, and cyst diameter and its interval changes (P=0.2-0.98). Emphysema was more frequently seen in smokers (P=0.002).

Table 2. Participant demographics based on existence of pulmonary cysts.

| No pulmonary cysts (N= 2433) |

Pulmonary cysts (N=200) |

P Value*1,2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age — year | 58.9 ± 12.0 (range 34.0, 92.0) | 63.0 ± 12.0 (range 40.1, 89.8) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Female sex — no. (%) | 1229 (51) | 96 (49) | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| Body-mass index*3 | 28.6 ± 5.4 (N=2420) |

27.1 ± 4.7 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Smoking status —no. (%) | |||

| Never | 1188 (49) | 80 (40) | 0.1 |

| Former | 1088 (45) | 108 (54) | 0.2 |

| Current | 150 (6) (N=2426) |

12 (6) | 0.7 |

|

| |||

| Pack-years | 17.9 ± 18.1 (N=1238) |

19.8 ± 17.6 (N=120) |

0.9 |

|

| |||

| Coronary artery calcium score*4 | 190.2 ± 530.9 (N=2303) |

167.9 ± 344.7 (N=188) |

0.006 |

|

| |||

| Respiratory symptoms — no. (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Chronic cough | 168 (7) | 8 (4) | 0.8 |

|

| |||

| Shortness of breath with minor exertion | 273 (11) | 18 (9) | 0.051 |

Plus-minus values are mean ± standard deviation.

P values were calculated with the use of mixed effect models or generalized estimation equations to account for familial relationships in the Framingham Heart Study, as described previously [15].

P values for BMI, smoking status, pack-years, coronary artery calcium score and respiratory symptoms were adjusted for age and sex. In addition, the result for coronary artery calcium score was adjusted for the presence of emphysema; the results for respiratory symptoms were adjusted for smoking status and pack-years.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by square of the height in meters.

Coronary artery calcium scores were calculated by the Agatston method [27].

Table 3. Characteristics of participants with pulmonary cyst stratified with smoking status.

| Non smoker (N=80) | Former and current smoker (N=120) | *1 P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age — year | 61.9 ± 12.6 (range 40.1, 89.8) |

63.7 ± 61.9 (range 41, 88.9) |

0.3 |

|

| |||

| Female sex — no. (%) | 37 (46) | 59 (49) | 0.7 |

|

| |||

| Body-mass index*2 | 26.8 ± 4.2 | 27.3 ± 5.0 | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| Emphysema — no. (%) | 1 (1) | 24 (20) | 0.002 |

|

| |||

| Cyst size (diameter) — mm | 11.2 ± 6.1 (range 4.0, 34.3) |

10.3 ± 4.5 (range 4.0, 30.3) |

0.2 |

|

| |||

| Interval change in diameter — no. (%) | |||

| Increased | 15 (38) | 24 (35) | 0.7 |

| Unchanged | 23 (58) | 45 (65) | 0.4 |

| Decreased | 2 (5) (N=40) |

0 (0) (N=69) |

- |

|

| |||

| Coronary artery calcium score*3 | 158.1 ± 331.1 (N=77) |

174.7 ± 355.1 (N=111) |

0.98 |

Plus-minus values are mean ± standard deviation.

P values for BMI, emphysema, cyst size, interval change, and coronary artery calcium score were adjusted for age and sex. In addition, the result for coronary artery calcium score was adjusted for the presence of emphysema.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by square of the height in meters.

Coronary artery calcium scores were calculated by the Agatston method [27].

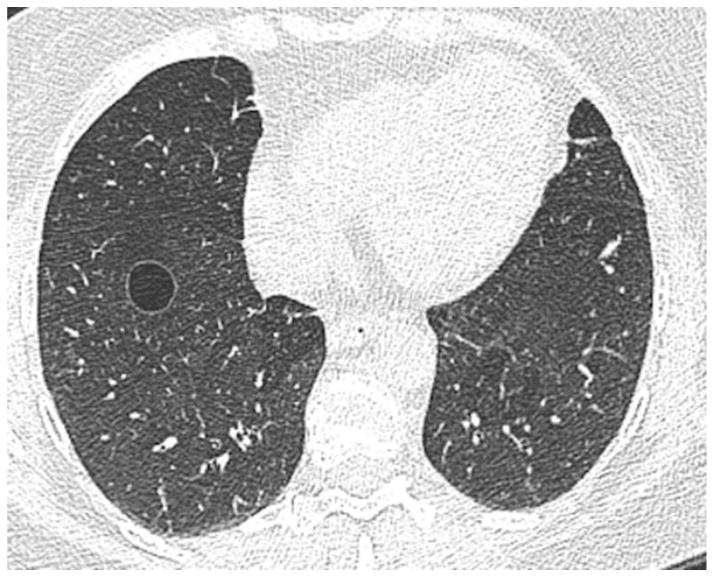

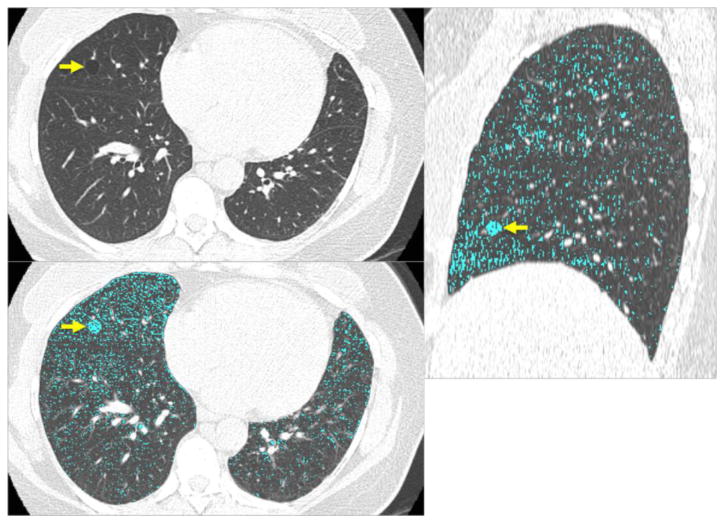

Emphysema was detected in 13% (350/2633). The details of the associations between emphysema and participant demographics will be discussed in a separate study. (Unpublished data). Pulmonary cysts were observed in 8% (25/350) of participants with emphysema (Figure 2) and in 8% (175/2283) of those without emphysema. There was no significant association between pulmonary cysts and emphysema (P=0.7).

Figure 2.

CT images of a 47-year-old female show a solitary round cyst (arrow) with a thin wall in the middle lobe of the right lung (a). She is a former smoker with 18 pack-years. (b) Low attenuation color-mapping overlaid images (threshold of -950 HU, indicated in light blue areas) at transaxial (b) and sagittal reconstruction (c) demonstrate the distinct solitary pulmonary cyst (arrows) with the background lung parenchyma with a diffuse infiltration of mild centrilobular emphysema.

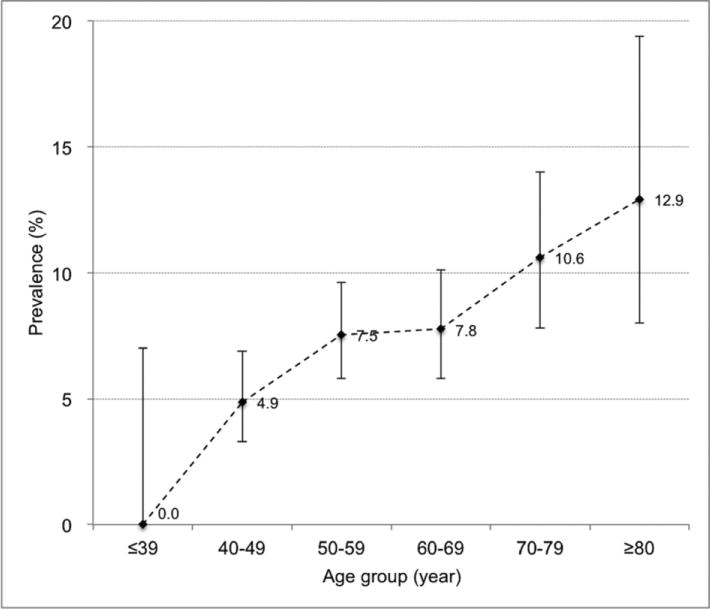

The prevalence of pulmonary cysts in different age decades is shown in Figure 3. The prevalence gradually increased with age, from 4.9% at age of 40-49 years to 12.9% at age older than 80 years. No participants younger than 39 years showed pulmonary cysts.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of pulmonary cysts in association with age. Plotted dots indicate the prevalence in each age group. Vertical lines extending from each plot represent 95% CI (confidence interval) with horizontal lines at the top and bottom representing upper and lower limits, respectively.

Results of pulmonary function tests are summarized in Table 4. Out of 2633 participants, 2468 had pulmonary function data (191 with pulmonary cysts and 2277 without). There was no significant difference in pulmonary functions (P=0.07-0.6), except for DLCO (P=0.03). Mean DLCO in those with pulmonary cysts was slightly but significantly reduced although still within normal limits (94% of predicted value).

Table 4.

Results of pulmonary function test of the participants based on the presence of pulmonary cysts.

| Parameters | No pulmonary cyst | Pulmonary cysts | P Value*1,2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 — % of predicted value*3 | 0.98 ± 0.15 (N=2277) |

0.99 ± 0.15 (N=191) |

0.2 |

| FVC — % of predicted value*3 | 1.02 ± 0.13 (N=2277) |

1.03 ± 0.13 (N=191) |

0.4 |

| FEV1 / FVC — % of predicted value*3 | 0.96 ± 0.09 < (N=2277) |

0.96 ± 0.09 < (N=191) |

0.6 |

| DLCO — % of predicted value*4 | 0.97 ± 0.16 (N=1895) |

0.94 ± 0.15 < (N=167) |

0.03 |

| Total lung capacity*5 — % of predicted value*6 | 0.84 ± 0.15 (N=2244) |

0.83 ± 0.15 (N=184) |

0.07 |

Plus-minus values are mean ± standard deviation.

FEV: forced expiratory volume, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FVC: forced vital capacity, DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

P values were calculated with the use of mixed effect models to account for familial relationships in the Framingham Heart Study, as described previously [15].

All the P values for variables of pulmonary function test were adjusted for age, smoking status (current, former, or never), and pack-years.

Predicted values for FEV1 and FVC are derived from Hankinson et al [28].

Predicted values for DLCO are derived from Miller et al [29].

Quantitative values for total lung capacity were calculated using Airway Inspector (www.airwayinspector.org).

Predicted values for total lung capacity are derived from the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society [30].

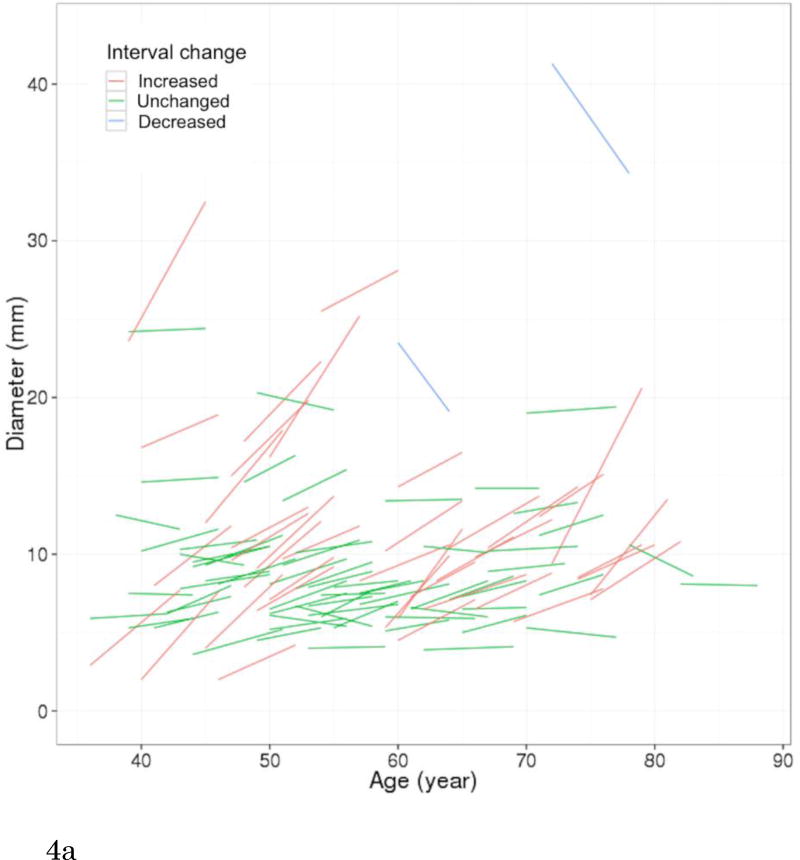

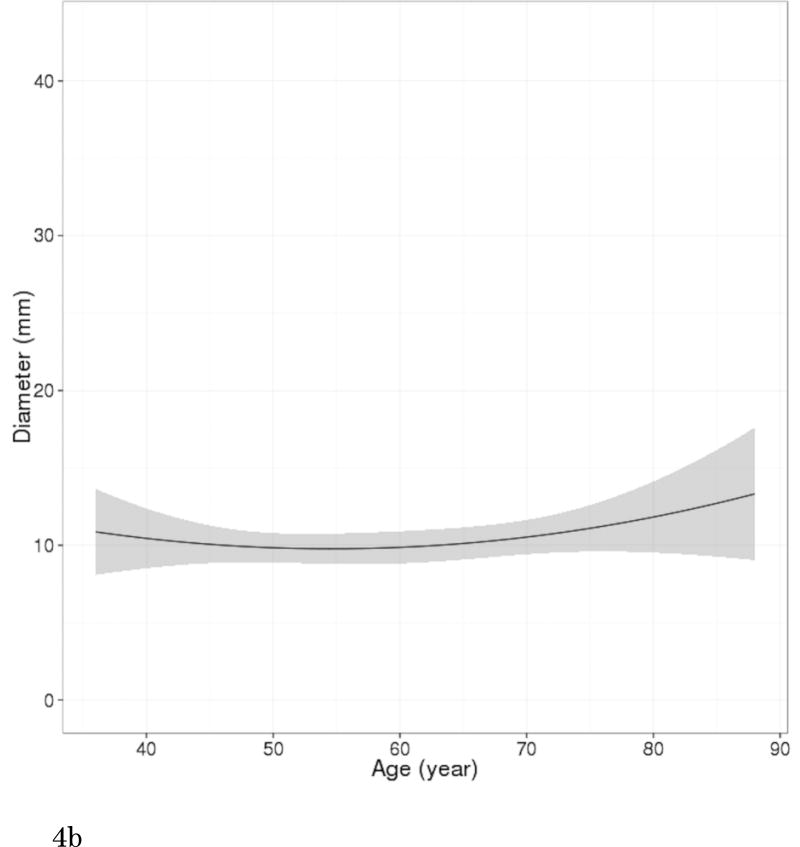

Of 200 participants with pulmonary cysts on MDCT2, 80 did not have comparable CT scans of MDCT1, 109 pulmonary cysts were also identified with MDCT1, and 11 did not have any identifiable pulmonary cysts on MDCT1 (regarded as newly appeared on MDCT2). CCCs for both intra- and interobserver agreement of measurements were substantial (CCC=0.99 [95%CI: 0.98-0.99] and 0.99 [95%CI: 0.98-0.99]. Bland-Altman plots showed that mean of absolute difference of measurements were -0.07 (95% CI limits: -1.73 to 1.59) and -0.23 (95% CI limits: -1.68 to 1.22) for intra- and interobserver variability (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). These results validate the threshold criteria of interval change of 2 mm. Interval changes of pulmonary cysts are shown in Figure 4. Over the median interval period of 6.1 years, 57% (68/120) showed no change, 33% (39/120) increased in diameter (Figure 5) and 9% (11/120) were newly found in the latest scans of MDCT2. Median diameter of pulmonary cysts on MDCT2 (9.5 mm) was slightly but significantly larger than that on MDCT1 (7.9 mm; P<0.001).

Figure 4.

Longitudinal observations of pulmonary cysts. (a) Participants (N=109) who had pulmonary cysts detected on both CT scans (MDCT1 and MDCT2, median interval of 6.1 years) are plotted for diameter of pulmonary cysts and participant's age. Each short line represents an interval change of a pulmonary cyst in diameter in each participant. Red lines (N=39) indicate increased in diameter, green lines (N=68) unchanged, and blue lines decreased (N=2). Increase or decrease in diameter was defined as changes in diameter of more than 2 mm accounting for measurement variability. (b) A curved-fit line represents an overall tendency, slight increase of the diameter of pulmonary cysts with age. Shaded area represents 95% CI (confidence interval).

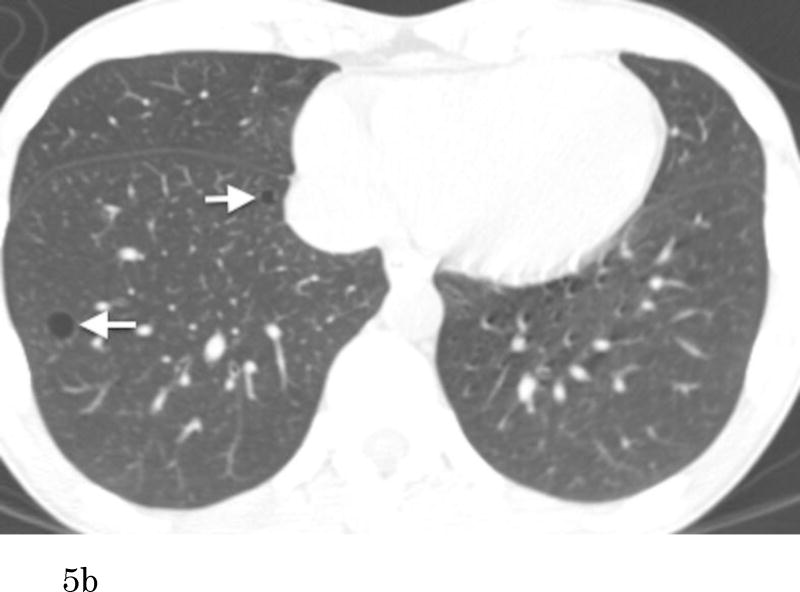

Figure 5.

Transaxial CT images at the lower level (a) of a 51-year-old female who has no smoking history show multiple thin-walled pulmonary cysts. These cysts are located predominantly in lower lobes, mostly in subpleural or peripheral areas. Comparison to the previous scan (b) (obtained 7.1-year previously) demonstrates an increase of the cysts in size and number. Cysts in the right lower lobe (a, b, arrows) increased in size (medial: 5 to 10 mm, lateral: 9 to 11 mm). The cyst in the middle lobe (a, arrowhead) was not detected on the previous image.

Discussion

The present study reveals that the prevalence of pulmonary cysts in the FHS is 7.6%, which increases with age. Pulmonary cysts appear in participants at 40 years or older, but not in those younger than 40 years. Pulmonary cysts are most likely to appear solitary in the peripheral area of the lower lobes and mostly remain unchanged but may slightly increase in size over time. Pulmonary cysts do not result in changes in spirometry and are not associated with cigarette smoking and emphysema.

In the studies by Copley et al [3] and Winter et al [4] with relatively small numbers of subjects, only the elderly groups (older than 65 or 75 years) had pulmonary cysts. The present study of a large population-based cohort revealed that pulmonary cysts can be seen even in middle-aged participants as young as 40 years. The prevalence of pulmonary cysts is 7.6% in the FHS cohort (mean age 59.2 years), which increases with age (4.9% at 40-49 to 12.9% at 80 or older). In addition, longitudinal observation revealed that most of the pulmonary cysts remain unchanged, but some may increase slightly in size. Pulmonary cysts did not result in reduced measures of spirometry. These findings may support the premise that pulmonary cysts found in asymptomatic individuals middle-aged or older are likely to be part of the aging changes of the lungs.

Pulmonary cysts may somewhat arbitrarily refer to various conditions with parenchymal destruction depending on the context, including bullous emphysema. However, pulmonary cysts should be differentiated from emphysema because emphysema is one of the major aspects of COPD and its clinical impact is of great significance [16]. Identification of a thin wall on CT may differentiate pulmonary cysts from emphysema. In addition, our study involved a direct comparison of the groups with emphysema and pulmonary cysts separately diagnosed on CT and revealed that these two entities occur independently. In the previous studies, it was not possible to discuss the association between age-related pulmonary cysts and emphysema because the presence of chronic lung diseases including emphysema was a part of exclusion criteria [3, 4, 6, 17]. Furthermore, some other findings also bolster the fact that pulmonary cysts are the distinct entity from emphysema: pulmonary cysts are not associated with smoking and tend to occur with the lower lobe predilection with no sex difference and no impairment of measures of spirometry, whereas emphysema predominantly occurs in the upper lobes, in male smokers [18]. However, there might be possible overlaps on CT findings between these two entities because compressed lung parenchyma adjacent to emphysematous lesions may show increased density, mimicking the thin wall of pulmonary cysts, which probably represent atelectasis or interlobular septa [19]. That is one of our motives for investigating vascular penetration: we expected that the finding could be suggestive of centrilobular emphysema because centrilobular pulmonary arteries or arterioles indicate the center of each lobule [19, 20]. However, there was no significant association detected between the specific image finding and the presence of emphysema.

Although pulmonary cysts are most likely to be solitary, they could be sporadic or sometimes multiple. The prevalence of multiple pulmonary cysts was 0.9% of all participants. In such cases, it is important to clinically exclude the possibility of the cystic lung diseases, such as PLCH, LAM, and LIP. Age is obviously useful for the differentiation. PLCH typically affects young adult smokers [21] and LAM primarily affects females of childbearing age [22, 23], whereas pulmonary cysts associated with aging rarely occur in these age groups. PLCH may appear with irregular cysts with a thicker wall in the upper lobes with or without nodular lesions. LAM may appear with a myriad of small cysts [22], whereas pulmonary cysts associated with aging mostly occur solitarily or in small numbers. LIP occurs in adults of middle age [22, 24]. However, associated image findings to LIP, such as diffuse or multifocal ground-grass opacities, thickening of bronchovascular bundles, and interlobular septal thickening, help differentiate it from age-related pulmonary cysts.

Notably, participants with pulmonary cysts showed significantly lower BMI than those without pulmonary cysts. A low BMI is known to be associated with the presence of emphysema, and nutritional depletion is regarded as one of the possible causes of emphysema [25]. Coxson et al revealed that a decrease in both BMI and DLCO are correlated with emphysema demonstrated with qualitative CT analysis [26]. Therefore, nutritional status influences the destruction of lung parenchyma and may play some roles in the development of pulmonary cysts as we found lower BMI in participants with pulmonary cysts. Our results showed that mean DLCO in those with pulmonary cysts was slightly but significantly lower, although within normal limits. We revealed pulmonary cysts are not associated with emphysema, and it is unlikely that small numbers of cysts may affect general lung function; in fact, FEV1 and FVC were not impaired. Therefore, the slight decrease of DLCO should be explained by something other than lung parenchymal destruction, for example, pulmonary vascular disease or anemic status. Our data does not strongly suggest that measures of coronary artery disease (e.g. coronary artery calcium scores) influence the development of pulmonary cysts as coronary artery calcium scores were rather reduced among those with pulmonary cysts. Another possible cause would be interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA) accompanied with pulmonary cysts [11]. However, additional analysis of ILA and pulmonary cysts in the present cohort did not reveal any significant association. Further study is necessary to induce rational explanations of cause of pulmonary cysts and the association between DLCO change and pulmonary cysts.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, our study lacks histopathological confirmation and mostly relies on CT findings. Therefore, the possibility that our cohort incidentally included participants with primary cystic lung diseases cannot be totally ruled out, although most of the participants were supposedly healthy individuals. Second, comparison of CT scans is not complete: not all of the cases with pulmonary cysts had comparable CT scans, which are cardiac scans with different protocols and insufficient coverage of the lungs. However, this is the first study that involved the largest number of participants with longitudinal observations of pulmonary cysts. Lastly, the FHS cohorts could be biased because participants of the FHS could be healthier than the general population due to substantial medical support and high health consciousness. However, investigation of the FHS cohorts provides a unique opportunity of epidemiological significance to investigate normal or aging changes such as pulmonary cysts, and makes this study distinctive from previous investigations of volunteers or patients recruited at hospital.

In conclusion, pulmonary cysts were identified in 7.6% on chest CT in the FHS and were associated with increased age. They were distinct from emphysema and not associated with smoking or impairment in measures of spirometry, suggesting that these pulmonary cysts could be mostly explained by the normal aging process of the lungs. The explanation of the associated decreases in DLCO and BMI requires further investigation. Multiple pulmonary cysts with its count of five or more may need to be scrutinized for the possibility of cystic lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Figure 2.

What is the key question?

What is the significance of pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT?

What is the bottom line?

Solitary or sporadic pulmonary cysts are associated with the aging of the lungs and multiple cysts (≥5), which are observed on CT images in less than 1% of participants, may be scrutinized for the possibility of cystic lung diseases.

Why read on?

This study provides an epidemiological overview of pulmonary cysts and reveals their imaging features, which may be useful for managing individuals with pulmonary cysts incidentally detected on CT.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge Alba Cid M.S. for editorial work on the manuscript.

Dr. Nishino is supported by NCI Grant Number: 1K23CA157631. Dr. Washko is supported by NIH Grant Number: R01 HL116473, R01 HL107246 and P01 HL114501. Dr. Hunninghake is supported by NIH Grant Number: K08 HL092222, U01 HL105371, P01 HL114501, and R01 HL111024. Dr. Hatabu is supported by NIH Grant Number: K25 HL104085 and R01 HL116473. This work was partially supported by the NHLBI's Framingham Heart Study contract: N01-HC-25195 and R01 HL111024.

References

- 1.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: Glossary of Terms for Thoracic Imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elicker BM, Webb WR. Fundamentals of High-Resolution Lung CT: Common Findings, Common Patters, Common Diseases and Differential Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copley SJ, Wells AU, Hawtin KE, Gibson DJ, Hodson JM, Jacques AE, et al. Lung morphology in the elderly: comparative CT study of subjects over 75 years old versus those under 55 years old. Radiology. 2009;251(2):566–73. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2512081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winter DH, Manzini M, Salge JM, Busse A, Jaluul O, Jacob Filho W, et al. Aging of the Lungs in Asymptomatic Lifelong Nonsmokers: Findings on HRCT. Lung. 2015;193(2):283–90. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9700-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vehmas T, Kivisaari L, Huuskonen MS, Jaakkola MS. Scoring CT/HRCT findings among asbestos-exposed workers: effects of patient's age, body mass index and common laboratory test results. European Radiology. 2005;15(2):213–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copley SJ, Giannarou S, Schmid VJ, Hansell DM, Wells AU, Yang GZ. Effect of aging on lung structure in vivo: assessment with densitometric and fractal analysis of high-resolution computed tomography data. Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 2012;27(6):366–71. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31825148c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuoka S, Uchiyama K, Shima H, Ueno N, Oish S, Nojiri Y. Bronchoarterial ratio and bronchial wall thickness on high-resolution CT in asymptomatic subjects: correlation with age and smoking. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 2003;180(2):513–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.2.1800513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KW, Chung SY, Yang I, Lee Y, Ko EY, Park MJ. Correlation of aging and smoking with air trapping at thin-section CT of the lung in asymptomatic subjects. Radiology. 2000;214(3):831–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.3.r00mr05831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendis S. The contribution of the Framingham Heart Study to the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global perspective. Progress in CardioVascular Diseases. 2010;53(1):10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Washko GR, Lynch DA, Matsuoka S, Ross JC, Umeoka S, Diaz A, et al. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Academic Radiology. 2010;17(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunninghake GM, Hatabu H, Okajima Y, Gao W, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, et al. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(23):2192–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revel M-P, Bissery A, Bienvenu M, Aycard L, Lefort C, Frija G. Are Two-dimensional CT Measurements of Small Noncalcified Pulmonary Nodules Reliable? Radiology. 2004;231(2):453–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312030167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kundel HL, Polansky M. Measurement of observer agreement. Radiology. 2003;228(2):303–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282011860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki T, Sholl LM, Gerbaudo VH, Hatabu H, Nishino M. Thymic Measurements in Pathologically Proven Normal Thymus and Thymic Hyperplasia: Intraobserver and Interobserver Variabilities. Academic Radiology. 2014;21(6):733–42. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uh HW, Wijk HJ, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ. Testing for genetic association taking into account phenotypic information of relatives. BMC proceedings. 2009;3(Suppl 7):S123. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-s7-s123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford ES, Croft JB, Mannino DM, Wheaton AG, Zhang X, Giles WH. COPD surveillance--United States, 1999-2011. Chest. 2013;144(1):284–305. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Well DS, Meier JM, Mahne A, Houseni M, Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Mong A, et al. Detection of age-related changes in thoracic structure and function by computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 2007;37(2):103–19. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Araki T, Nishino M, Zazueta OE, Gao W, Dupuis J, Okajima Y, et al. Paraseptal Emphysema: Prevalence and Distribution on CT and Association with Interstitial Lung Abnormalities. European Journal of Radiology. 2015;84(7):1413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch DA, Austin JH, Hogg JC, Grenier PA, Kauczor HU, Bankier AA, et al. CT-Definable Subtypes of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2015;141579 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murata K, Itoh H, Todo G, Kanaoka M, Noma S, Itoh T, et al. Centrilobular lesions of the lung: demonstration by high-resolution CT and pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1986;161(3):641–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.3.3786710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbott GF, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Franks TJ, Frazier AA, Galvin JR. From the archives of the AFIP: pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Radiographics. 2004;24(3):821–41. doi: 10.1148/rg.243045005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantin L, Bankier AA, Eisenberg RL. Multiple cystlike lung lesions in the adult. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 2010;194(1):W1–W11. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryu JH, Moss J, Beck GJ, Lee JC, Brown KK, Chapman JT, et al. The NHLBI lymphangioleiomyomatosis registry: characteristics of 230 patients at enrollment. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;173(1):105–11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1298OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johkoh T, Muller NL, Pickford HA, Hartman TE, Ichikado K, Akira M, et al. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology. 1999;212(2):567–72. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.2.r99au05567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa E, Nakano Y, Ohara T, Muro S, Hirai T, Sato S, et al. Body mass index in male patients with COPD: correlation with low attenuation areas on CT. Thorax. 2009;64(1):20–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.097543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coxson HO, Chan IH, Mayo JR, Hlynsky J, Nakano Y, Birmingham CL. Early emphysema in patients with anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004;170(7):748–52. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-651OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R., Jr Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1990;15(4):827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller A, Thornton JC, Warshaw R, Anderson H, Teirstein AS, Selikoff IJ. Single breath diffusing capacity in a representative sample of the population of Michigan, a large industrial state. Predicted values, lower limits of normal, and frequencies of abnormality by smoking history The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1983;127(3):270–7. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stocks J, Quanjer PH. Reference values for residual volume, functional residual capacity and total lung capacity. ATS Workshop on Lung Volume Measurements. Official Statement of The European Respiratory Society The European Respiratory Journal. 1995;8(3):492–506. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Figure 2.