Abstract

Objective

FDA is considering an application for a biosimilar infliximab, which has been available in South Korea since November 2012. We aimed to examine the utilization patterns of both branded and biosimilar infliximab and other TNF in South Korea before and after the introduction of biosimilar infliximab.

Methods

Using the claims data (4/2009–3/2014) of the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database, which includes the entire South Korean population, we assessed the uptake of biosimilar infliximab. A segmented linear regression model examined utilization patterns of infliximab (the branded and biosimilar) and other TNF inhibitors (adalimumab and etanercept) before and after the introduction of biosimilar infliximab.

Results

We identified 20,976 TNF inhibitor users, including 983 users of biosimilar infliximab. Among all the claims for any infliximab version, the proportion of biosimilar infliximab claims increased to 19% through March 2014. Before November 2012, each month there were 33 (95%CI 32–35) more infliximab claims, 44 (95%CI 40–48) more etanercept claims, and 50 (95%CI 47–53) more adalimumab claims. After November 2012, there were significant changes in the slopes with additional increases in the use of branded and biosimilar infliximab (9 claims/month, 95%CI 2–17) and decreases in etanercept (−52 claims/month, 95%CI −66 to −38) and adalimumab (−21 claims/month, 95%CI −35 to −6).

Conclusion

After 15 months since its introduction in Korea, one-fifth of all infliximab claims were for the biosimilar. Introduction of biosimilar infliximab may affect the use of other TNF inhibitors and the magnitude of change will likely differ in other countries.

Keywords: Biosimilar, infliximab, utilization

INTRODUCTION

Development of biologic drugs such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors has been a major advance in treatment of systemic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory bowel disease. While TNF inhibitors are highly effective in controlling systemic inflammation, their high costs make them unavailable to many patients and reduce patient adherence. Biosimilars are being developed as a potential way to create market competition among biologic products, reduce cost and improve access to biologic therapy for systemic inflammatory disease, since competition from approved biosimilars has been estimated to generate 20–30% savings over the cost of the branded versions of biologic drugs.(1)

A biosimilar to infliximab, the first biosimilar drug of large, complex monoclonal antibody, is currently approved in a number of countries including South Korea, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Canada for RA and other systemic inflammatory diseases.(2) In a pivotal double-blind, multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 606 active RA patients despite use of methotrexate, the biosimilar infliximab was noted to have equivalent efficacy to the branded infliximab at week 30 with a similar safety profile.(3) Another RCT of 250 patients with active ankylosing spondylitis also showed equivalent efficacy of the biosimilar infliximab vs. the branded infliximab at week 30.(4) The U.S. FDA is currently considering an application for a biosimilar version of infliximab (3, 4) from the same manufacturer that has supplied the drug to South Korea since November 2012. Due to the lower cost of the biosimilar infliximab, the cost of the branded infliximab in Korea was lowered by 30% immediately after the biosimilar became available.

The objectives of this study were to assess the uptake of biosimilar infliximab and to examine the utilization patterns of both branded and biosimilar infliximab and other TNF inhibitors including etanercept and adalimumab in South Korea before and after the introduction of biosimilar infliximab in November 2012.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

South Korea has universal healthcare insurance coverage, which covers approximately 97% of the total population of 50 million. The suitability of reimbursement of all the medical claims including prescriptions submitted by individual health care providers is reviewed by the government agency called the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA). The HIRA database contains patients’ demographic data such as age, gender, medical diagnoses using the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision (ICD-10) codes, procedures or operations, drug claims, medical care costs and healthcare provider characteristics. This database has been used in a number of pharmacoepidemiologic studies.(5–7) Using the medical claims data from the HIRA, we identified patients at any age who used the branded or biosimilar infliximab and other TNF inhibitors including adalimumab and etanercept for any indication during the 5-year period between April 2009 and March 2014. Certolizumab pegol and golimumab were not available in Korea during the study period.

Data Analysis

We assessed patients’ demographic characteristics and described trends in the use of the branded or biosimilar infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept. A segmented linear regression model was used to examine utilization patterns of infliximab (the branded and biosimilar) and other TNF inhibitors (adalimumab and etanercept) before and after the introduction of the biosimilar infliximab. This model included the number of claims each month as the outcome variable, intercept and two slope terms that described the trend in use of TNF inhibitors per month before and after introduction of the biosimilar infliximab in November 2012. We did not include a term for a step change on introduction of the biosimilar infliximab, as we did not expect an immediate impact of the product. Newey-West standard errors were used to allow for autocorrelation up to the second order.(8) All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 and STATA 13.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Seoul National University Hospital. Patient informed consent was not required, as the dataset was de-identified.

RESULTS

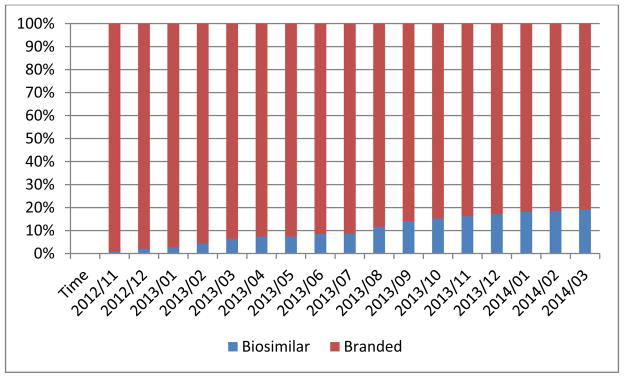

We identified a total of 20,976 patients who had at least 1 dispensing for adalimumab, etanercept, branded infliximab, or biosimilar infliximab during the study period. The mean age was 43 (SD 15) years and 56% were male. There were 7,274 patients who had at least 1 dispensing for either branded or biosimilar infliximab. Of these, 983 used biosimilar infliximab since its introduction in November 2012. Nearly half (41%) of biosimilar infliximab users were switched from the branded infliximab. Among all the claims for any infliximab version, the proportion of biosimilar infliximab claims increased to 19% through March 2014 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Uptake of infliximab biosimilar among all infliximab uses since its market introduction.

X-axis is calendar time.

The use of all TNF inhibitors increased significantly over time with the number of claims approximately tripling from 3,117 in April 2009 to 9,278 in March 2014. Prior to introduction of biosimilar infliximab, each month there were 33 (95%CI, 32–35) more infliximab claims, 44 (95%CI, 40–48) more etanercept claims, and 50 (95%CI, 47–53) more adalimumab claims (Figure 2). After introduction of biosimilar infliximab, there was a significant change in the slopes with an additional increase in the use of both branded and biosimilar infliximab (9 claims/month, 95%CI, 2–17) and decreases in the use of etanercept (−52 claims/month, 95%CI, −66 to −38) and adalimumab (−21 claims/month, 95%CI, −35 to −6).

Figure 2. Trends in use of all TNF-α inhibitors before and after market introduction of biosimilar infliximab.

The Infliximab line after November 2012 includes both the branded and biosimilar.

DISCUSSION

With the recent expiration of patents around the world protecting numerous high-cost branded biologic drugs, biosimilars have been developed and introduced in several countries, offering competition and reduced prices.(9) In Korea, we found that uptake of a newly-introduced biosimilar infliximab reached one-fifth of all infliximab prescribing by 15 months. Cost-savings from biosimilar infliximab in Korea would have emerged from its use, its contribution to the price change in branded infliximab, as well as its collateral effect on use of other TNF blockers, which demonstrated slower uptake after its introduction.

When new generic small-molecule drugs first reach the market, they often quickly overtake prescribing of the brand-name version;(10) by contrast, we found relatively slow uptake of biosimilar infliximab. One reason for the difference is that in the former case, substitution is driven by pharmacy-level substitution laws that consider brand-name and generic small molecule drugs interchangeable, while biosimilar infliximab needs to be specifically prescribed by a physician in Korea. Physicians may be hesitant to switch patients currently taking branded TNF inhibitors to a biosimilar agent, because of concerns about immunogenicity in patients exposed to different versions of the same biologic drug. It is possible that physicians would be more likely to consider a biosimilar over the branded biologic agent in biologic-naive patients,(11) but any financial considerations in this decision were undercut by the branded infliximab’s price reduction in the Korean market.

Our study has limitations. We were unable to study why patients were switched from the branded to the biosimilar infliximab. We did not evaluate patterns of the biosimilar infliximab and other TNF inhibitor use for a specific indication.

Despite these limitations, our results have important implications as growing numbers of biosimilars to treat rheumatologic and other conditions are approved the U.S., Korea, and elsewhere around the world. First, since automatic substitution of biologics is not the norm in the countries where biosimilars are currently being used and not expected in the U.S., rapid uptake will not be observed. Since biosimilars may be able to offer cost-savings to patients and payors as originally intended by the Affordable Care Act in 2010, mechanisms should be in place to promote patient and physician awareness of them and encourage appropriate use. At the same time, systematic post-approval trials and observational studies using longitudinal patient registry or electronic medical record data linked with claims data can monitor the treatment pattern of biosimilar and may help assess the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars. Reflecting these dual goals, in 2011, the American College of Rheumatology issued a position statement that safe and effective treatments should be available to patients at the lowest possible cost, but also raised several cautions regarding the need for different names of biosimilars from their reference drugs and solid evidence on bioequivalence of the biologics, efficacy, toxicity, and long-term safety profile.(12) In August 2015, the FDA released a draft guidance for industry that detailed the FDA’s proposal on the nonproprietary naming of biological products such as biosimilars to ensure safe use of these drugs.(13)

Introduction of biosimilar infliximab in Korea led to a lower-cost new product that gained substantial market share, impacting the use of more expensive alternatives. About 40% of RA patients in the U.S. receive a biologic drug,(14) while the use of biologic drugs is less common in Korea, with approximately 3% of RA patients being treated with a biologic.(15) Thus, an approved biosimilar infliximab product could have an even more significant impact on the overall use and costs of biologic therapy in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

Other Research funding Support: SCK is supported by the NIH grant K23 AR059677. ASK is a Greenwall Faculty Scholar and received grant support from the FDA Office of Generic Drugs and Division of Health Communication. DHS is supported by NIH K24 AR055989.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: All authors conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SCK, NKC, JL, KK, and WE analyzed the data. SCK drafted the paper. NKC had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interest disclosures: No specific funding was given for this study.

SCK receives salary support from unrelated grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Lilly. DHS receives salary support from unrelated grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, and AstraZeneca. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Seoyoung C Kim, Email: skim62@partners.org.

Nam-Kyong Choi, Email: likei1@snu.ac.kr.

Joongyub Lee, Email: denver261@gmail.com.

Kyoung-Eun Kwon, Email: smilekwon@snu.ac.kr.

Wesley Eddings, Email: weddings@partners.org.

Yoon-Kyoung Sung, Email: sungyk@hanyang.ac.kr.

Hong Ji Song, Email: hongjisong5@gmail.com.

Aaron S. Kesselheim, Email: akesselheim@partners.org.

Daniel H. Solomon, Email: dsolomon@partners.org.

References

- 1.Ayers DC, Franklin PD, Ring DC. The role of emotional health in functional outcomes after orthopaedic surgery: extending the biopsychosocial model to orthopaedics: AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):e165. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo DH. The rise of biosimilars: potential benefits and drawbacks in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10(8):981–3. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.932690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, Ramiterre E, Piotrowski M, Shevchuk S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1613–20. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, Kovalenko V, Lysenko G, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1605–12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SC, Kim MS, Sanfelix-Gimeno G, Song HJ, Liu J, Hurtado I, et al. Use of osteoporosis medications after hospitalization for hip fracture: a cross-national study. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):519–26. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt N, Chan EW, Choi NK, Kimura M, Kimura T, Kubota K, et al. Prescription sequence symmetry analysis: assessing risk, temporality, and consistency for adverse drug reactions across datasets in five countries. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pds.3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi NK, Chang Y, Kim JY, Choi YK, Park BJ. Comparison and validation of data-mining indices for signal detection: using the Korean national health insurance claims database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(12):1278–86. doi: 10.1002/pds.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stock JH, Watson MMHP. Introduction to Econometrics. 2. Boston: Pearson/Addison-Wesley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheinberg M, Castaneda-Hernandez G. Anti-tumor necrosis factor patent expiration and the risks of biocopies in clinical practice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(6):501. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Agnew-Blais J, Federman AD, Liberman JN, Liu J, et al. State generic substitution laws can lower drug outlays under Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(7):1383–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baji P, Gulacsi L, Lovasz BD, Golovics PA, Brodszky V, Pentek M, et al. Treatment preferences of originator versus biosimilar drugs in Crohn’s disease; discrete choice experiment among gastroenterologists. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1054422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rheumatology ACo. POSITION STATEMENT: Biosimilars. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA. Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products Guidance for Industry. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SC, Yelin E, Tonner C, Solomon DH. Changes in use of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for rheumatoid Arthritis in the U.S. for the period 1983–2009. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(9):1529–33. doi: 10.1002/acr.21997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung YK, Cho SK, Choi CB, Bae SC. Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in South Korea. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(6):1525–32. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]