Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is an increasingly serious public health threat1. Understanding pathways allowing bacteria to survive antibiotic stress may unveil new therapeutic targets2–8. We explore the role of the bacterial epigenome in antibiotic stress survival using classical genetic tools and single-molecule real-time sequencing to characterize genomic methylation kinetics. We find that Escherichia coli survival under antibiotic pressure is severely compromised without adenine methylation at GATC sites. While the adenine methylome remains stable during drug stress, without GATC methylation, methyl-dependent mismatch repair (MMR) is deleterious, and fueled by the drug-induced error-prone polymerase PolIV, overwhelms cells with toxic DNA breaks. In multiple E. coli strains, including pathogenic and drug-resistant clinical isolates, DNA adenine methyltransferase deficiency potentiates antibiotics from the β-lactam and quinolone classes. This work indicates that the GATC methylome provides structural support for bacterial survival during antibiotics stress and suggests targeting bacterial DNA methylation as a viable approach to enhancing antibiotic activity.

Bacteria exposed to antibiotics mount complex stress responses that promote survival9–14, and accumulating evidence suggests that inhibiting such responses potentiates antimicrobial activity in drug-sensitive, tolerant and resistant organisms2,3,5,8,15–18. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, genetic pathways underlying responses to environmental insults have been widely studied and involve some of the most phylogenetically conserved proteins known19. In eukaryotes, stress can also elicit epigenetic modification of histones and DNA that support long-lasting downstream responses20–23. The role of prokaryotic epigenomes in stress, however, is much less clear.

Bacteria lack histones, but harbor a diverse group of enzymes able to insert epigenetic modifications in the form of sequence-specific methylation of DNA bases24. Prokaryotic DNA methyltransferases (MTases) function either alone or as part of restriction-modification systems, participating in various cellular processes including anti-viral defense, cell cycle regulation, DNA replication and repair, and transcriptional modulation24–26. While several methylation-dependent epigenetic switches have been described27–32, genome-wide methylation patterns and kinetics have, until recently, been difficult or impossible to study in a high-throughput manner33–36. In this study, we use genetic and genomic tools to explore the function and behavior of the bacterial methylome during antibiotic stress.

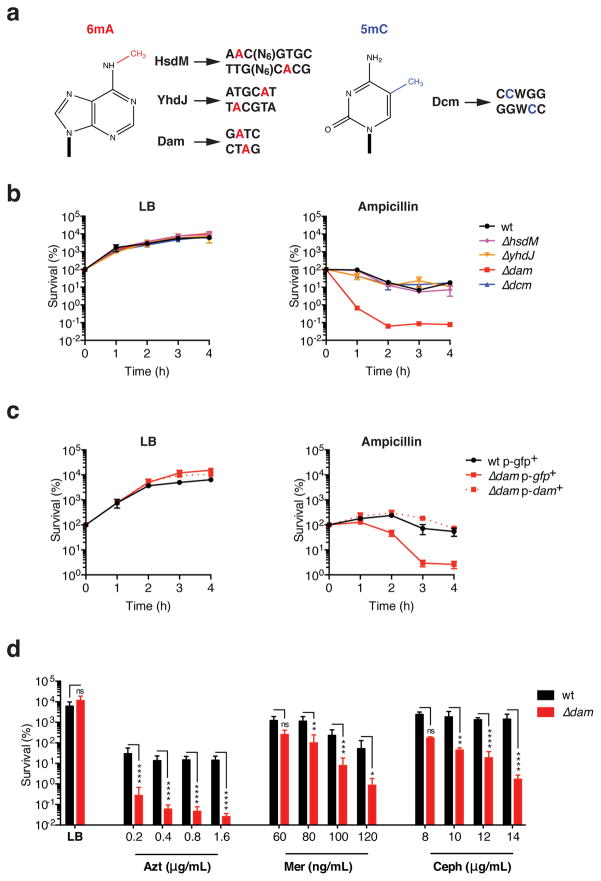

To assess the role of DNA methylation in antibiotic stress survival, we first tested the ability of E. coli lacking different MTases to withstand sub-lethal doses of β-lactam antibiotics. Laboratory E. coli K12 possesses four functional MTases that methylate adenines or cytosines within distinct target sequences24,36–40 (Fig. 1a). Survival of sub-inhibitory ampicillin exposure by log-phase E. coli was unaffected in mutants lacking HsdM, YhdJ or Dcm MTases. However, bacteria deficient in DNA adenine methyltransferase (Dam) were highly susceptible to this low drug dose (Fig. 1b and Sup. Fig. 1a,b). Increased ampicillin susceptibility in dam-deficient E. coli was also reflected in a reduced minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) (Sup. Fig. 1c). Complementation with a plasmid expressing dam, but not gfp, restored wild-type survival levels in Δdam E. coli (Fig. 1c, Sup. Fig. 2a, b). Because Dam might also behave as a transcriptional repressor independently of its DNA methyltransferase function37, we tested the ability of plasmids expressing previously characterized methylation-incompetent Dam variants38 (Sup. Fig. 2a) to rescue ampicillin hypersensitivity in Δdam E. coli. Consistent with a role for GATC methylation, mutant Dam expression minimally altered the ampicillin hypersensitivity of Δdam E. coli, if at all (Sup. Fig. 2b, c). Finally, we sought to determine whether Δdam E. coli hypersensitivity extended to drugs other than ampicillin. Sub-inhibitory treatment with aztreonam, meropenem and cephalexin, other β-lactams commonly used in the clinic, was also significantly potentiated in the absence of dam (Fig. 1d). Together, these results suggest that Dam-dependent methylation is important for bacterial survival during β-lactam stress.

Figure 1. Increased sensitivity to β-lactams in the absence of dam methylation.

a. DNA methylation in E. coli K12: methylated DNA bases, methyltransferases (MTases) and their respective target sequences. b. Wild type (wt) or MTase-deficient E. coli BW25113 were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) to an OD of 0.3, then treated with 2.5 μg/mL of ampicillin (~0.5 × MIC) or left untreated. c. Log-phase wild-type or dam-deficient E. coli harboring the indicated Cmr plasmid expressing either dam or gfp were cultured in chloramphenicol (15 μg/mL)-supplemented LB with or without ampicillin (2.5 μg/mL). d. wild-type or Δdam E. coli grown to an OD of 0.3 were treated for 4h with the indicated drugs. Azt, aztreonam; Mer, meropenem; Ceph, cephalexin. In b–d, survival was determined by monitoring colony-forming units (CFU) in bacterial cultures at the indicated timepoints, and is expressed relative to CFU at 0h. Mean percent survival ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments is shown; ns, not significant; *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

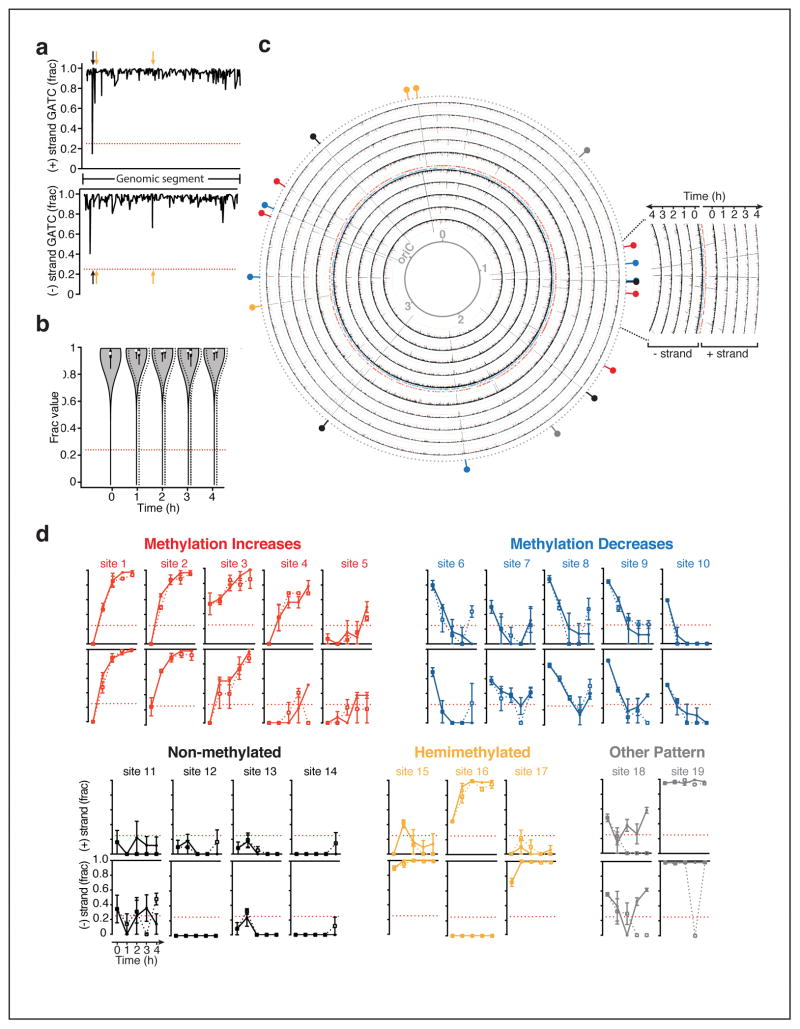

Dam methylates GATC sites throughout the genome of organisms belonging to multiple orders of γ-proteobacteria, including the clinically relevant genera Escherichia, Salmonella, Yersinia and Vibrio24. To explore the behavior of the Dam methylome in the context of antibiotic pressure, we extracted genomic DNA from E. coli growing in the presence or absence of ampicillin stress, and analyzed genome-wide GATC methylation over time using single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing. With SMRT technology, epigenetic modifications on template DNA strands are inferred through the unique kinetic signature they engender during sequencing35,39, and the fraction of DNA molecules methylated (‘frac’) at each GATC site is estimated (Fig. 2a). In all samples, consistent with Dam’s processive kinetics40, the majority of GATC sites were detected as methylated in a high fraction of DNA molecules sequenced (0.97±0.05 on average) (Fig. 2b, Sup. Data Set 1). Notably, during the log-to-stationary phase transition, we identified 19 GATC sites that appeared transiently or stably non-methylated, or hemimethylated (Fig. 2c, d; Sup. Table 1, 2; Sup. Data Set 1). Transiently non-methylated sites typically became steadily more or less methylated over time, following clear temporal patterns (Fig. 2c, d). Because prokaryotes lack demethylases, non-methylated GATC sequences exist mainly where DNA-binding proteins sterically hinder Dam activity immediately following DNA replication24. Consistent with this notion, 18 of these 19 sites fell within intergenic regions, mostly overlapping with or closely neighboring footprints of transcription factors (Sup. Table 1). To our knowledge, only five of these sites have been previously reported as protected24,41–44.

Figure 2. Kinetics of the Dam methylome during normal growth or under antibiotic stress.

Genomic DNA extracted from wild-type E. coli MG1655 growing with or without ampicillin (2.5 μg/mL) was analyzed by SMRT sequencing for genome-wide GATC methylation over 4h. Methylation is shown as the average fraction of sequenced molecules methylated for each GATC site, or ‘frac;’ dottted red lines indicate the limit of detection (0.25) a. Representative frac data for untreated bacteria; X-axis, position on selected genomic segment; arrows non-methylated (black) or hemimethylated (orange) GATC sites. b. Genome-wide frac distributions during growth in LB (solid line, gray fill) or ampicillin (dashed line, no fill) over time; mean frac ± SD are shown. c. Genome-wide kinetics of adenine methylation at GATC sites during log-to-stationary phase growth in LB; black lines indicate frac values as shown in (a); colored hashes show the position of genes either strands; the innermost ring is a reference map of genomic positions in megabases; oriC, origin of replication; colored indicators on the outer most ring highlight sites detected as non-methylated (frac<0.025, coefficient of variation<0.5) in at least one sample set, with colors corresponding to methylation increase (red) or decrease (blue) over time, stable non-methylation (black), hemimethylation (orange) or other (gray). d. Methylation kinetics for untreated (solid line) and ampicillin-treated (dotted line) E. coli at GATC positions that are non-methylated in at least one sample; x axis, time; mean frac ± SEM of n = 2–3 independent experiments is shown.

Remarkably, the GATC methylome and its kinetics were largely unaltered by ampicillin stress. The genome-wide distribution of frac values was similar in treated and untreated cells over time, indicating that global methylation levels were not increased or decreased by drug exposure (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, methylation at the vast majority of GATC sites, including those displaying dynamic methylation patterns, remained unchanged by treatment (Fig. 2d, Sup. Table 2, Sup. Data Set 1). Comparison of treated versus untreated samples at each timepoint revealed only one GATC site (site 19) displaying statistically significant differential methylation, which occurred at a single timepoint and only on one strand (Sup. Table 2, Sup Fig. 3). This event’s biological consequence is unclear, however, as expression of the surrounding gene (gdhA) was unperturbed by ampicillin treatment (data not shown). Thus, ampicillin stress does not majorly alter the E. coli Dam methylome.

Given the remarkable stability of adenine methylation during antibiotic exposure and the contrasting drug-sensitive phenotype of dam-deletion mutants, we reasoned that the GATC methylome must provide structural rather than regulatory support for bacterial survival during antibiotic stress. Widespread genomic Dam methylation enables cellular processes requiring discrimination between the fully methylated parental DNA strand, and newly synthesized DNA whose GATC sites are not yet modified45. Specifically, transient hemimethylation at replication forks orients the methyl-dependent mismatch repair (MMR) system, guiding replacement of mismatched bases to nascent DNA strands only46. Importantly, without GATC methylation, the methyl-dependent endonuclease MutH can introduce double-strand breaks (DSB) near mismatches targeted for repair47–51. Mismatches are rare in log-phase E. coli52 (<1 per replication cycle), but under conditions of stress, their frequency can increase due in part to induction of the error-prone polymerase IV (PolIV, encoded by dinB)53–55. We thus hypothesized that potentiation of β-lactam killing in the absence of Dam was a result of drug-induced mutagenesis fueling a genotoxic MMR pathway.

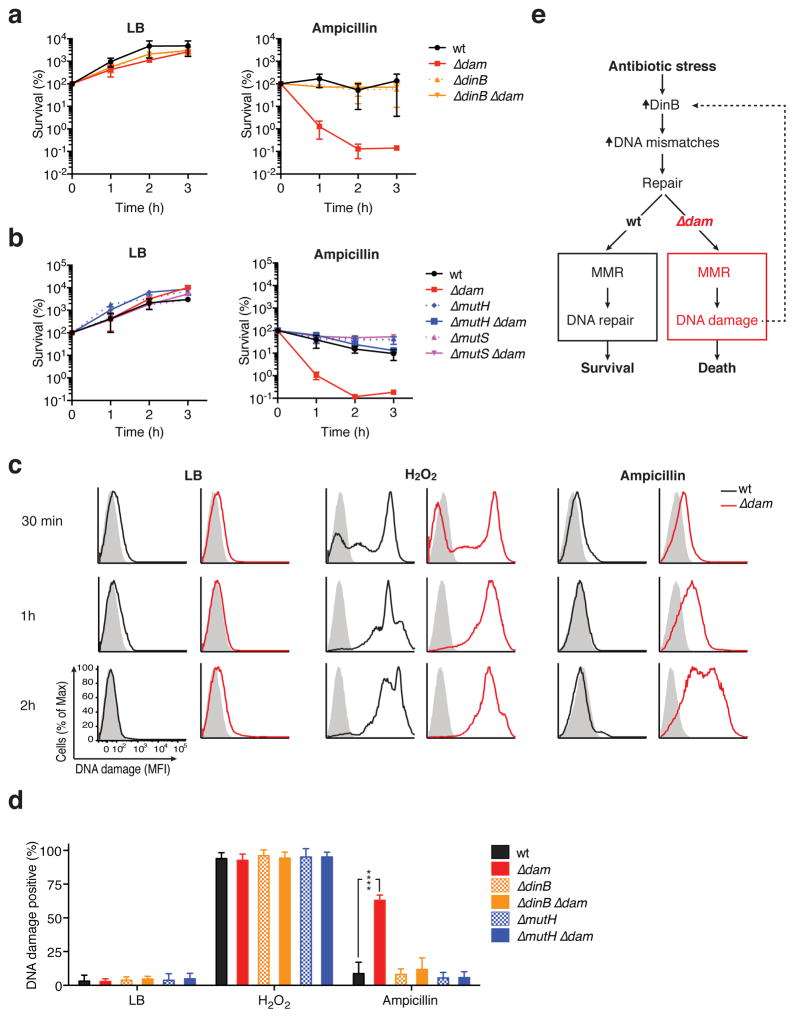

To test this, we assessed the effect of deleting dinB, mutH or the mismatch-binding component of the MMR complex, mutS, on antibiotic hypersensitivity in Δdam bacteria. Strikingly, without the mutagenic polymerase PolIV, Δdam E. coli survival of ampicillin stress returned to wild-type levels (Fig 3a; Sup. Fig. 4a). Similarly, removal of mutS or mutH on the Δdam background also abrogated ampicillin hypersensitivity (Fig. 3b, Sup. Fig. 4b). In ΔmutH Δdam bacteria, optical density (OD) was somewhat diminished in ampicillin (Sup. Fig. 4b), but this did not reflect decreased viability during treatment (Fig. 3b). Further consistent with our hypothesis, we found that Δdam, but not ΔdinB Δdam or ΔmutH Δdam bacteria, developed significantly more DNA damage than wild-type cells during ampicillin treatment, as assessed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase nick end-labeling (TUNEL)56 (Fig. 3c, d). Thus, without the GATC methylome, β-lactam-elicited PolIV introduces mismatches that are converted into lethal DNA strand breaks by a deleterious MMR system (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3. PolIV-dependent mutagenesis fuels MMR-mediated DNA damage in β-lactam-stressedΔdam E. coli.

a–b. The indicated E. coli BW25113 strains were grown in LB to an OD of 0.3, then treated with ampicillin (2.5 μg/mL) or left untreated. CFU in bacterial cultures were monitored hourly to assess survival. Mean percent survival ± SEM of n = 2 independent experiments is shown. c. Log-phase E. coli grown in LB alone, with hydrogen peroxide (100 mM) or with ampicillin (2.5 μg/mL) for the indicated time were assayed for DNA breaks by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) nick end labeling (TUNEL). The fluorescence distribution of each sample incubated with fluorescent label in the presence (solid line) or absence (shaded histogram) of TdT is displayed. A representative experiment is shown; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. d. DNA damage as assessed as in (c) at 1hr. Mean percent DNA damage positive ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments is shown; statistical comparisons between each mutant strain and wild-type were not significant unless otherwise indicated; ****, p<0.0001. e. Schematic model of antibiotic potentiation in the absence of Dam methylation.

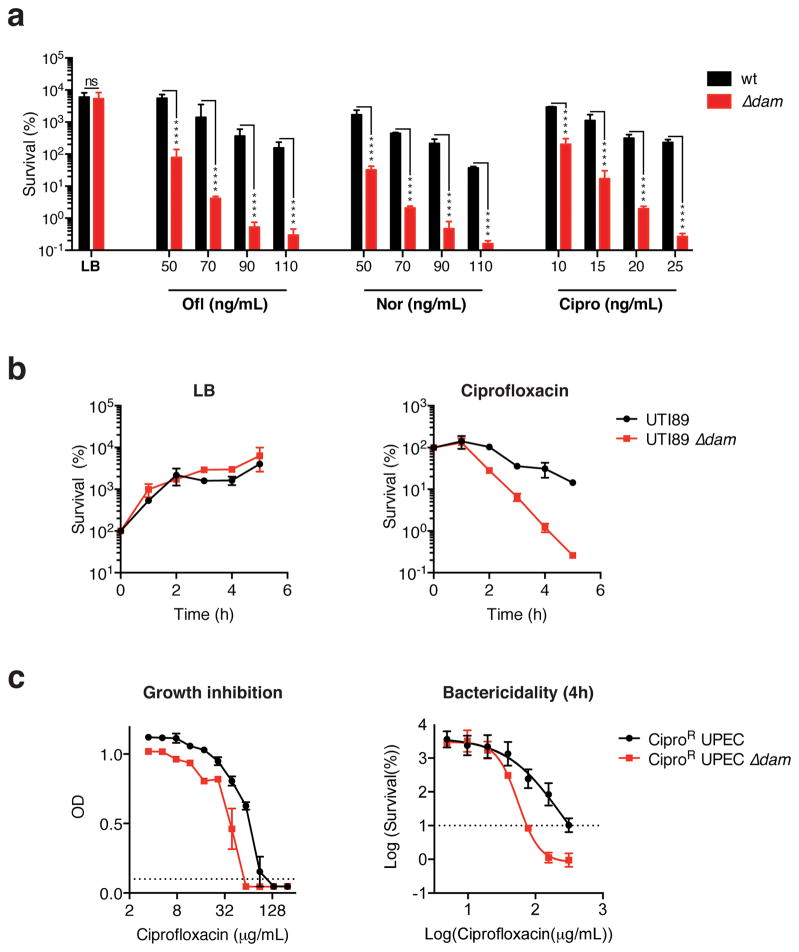

The finding that genomic GATC methylation supports β-lactam stress survival in E. coli evokes the possibility of targeting Dam to therapeutically potentiate antibiotic drug activity. Dam is an attractive target as it lacks mammalian homologs but is conserved in several enteric pathogens57–59. Furthermore, because muliple drugs can induce mutagenic responses in bacteria9,12,55,60–62, treatment with antibiotics other than β-lactams should also be potentiated in the absence of GATC methylation. Indeed, survival of dam-deficient E. coli in the presence of sub-inhibitory doses of the quinolones norfloxacin, ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin was severely compromised compared to wild-type bacteria (Fig. 4a). As seen with ampicillin, hypersensitivity to ofloxacin could be abrogated by deleting dinB, mutH or mutS, in Δdam E. coli (Sup. Fig. 5a, b). Consequently, drug potentiation in the absence of GATC methylation occurs via a similar mechanism across different antibiotic classes, and may be broadly exploitable.

Figure 4. Quinolone toxicity is potentiated in laboratory and pathogenic Δdam E. coli.

a. wild-type or Δdam E. coli BW25113 grown to an OD of 0.3 were treated for 3h with or without the indicated drugs. b. Log-phase UTI89 uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) or Δdam UTI89 was treated with 15ng/mL of ciprofloxacin or left untreated. Mean percent survival (compared to t = 0h) ± SEM of n = 2 independent experiments is shown. c. Determination of ciprofloxacin MIC, left panel, and MBC90, right panel, for CiproR UPEC by broth microdilution in LB. wild-type and Δdam MIC are 133 μg/mL and 59 μg/mL, respectively; wild-type and Δdam MBC90 are 316 μg/mL and 68 μg/mL, respectively. Dotted lines indicate cut-off values for MIC (OD<0.1) or MBC90 (10% survival), MBC90 values were interpolated using a sigmoidal curve fit model as shown. In a–c, means ± SEM of n = 2–3 independent experiments is shown; ns, not significant; ****, p<0.0001.

Next, we sought to determine whether virulent clinical isolates could also be sensitized to treatment by the removal of Dam. As in E. coli K12, dam deletion in uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) UTI8963 significantly increased sensitivity to ciprofloxacin (Fig. 4b). Ciprofloxacin is a valuable drug for UPEC treatment, but its use is increasingly restricted by the spread of quinolone resistance64. To assess whether targeting Dam might allow re-sensitization of resistant strains, we deleted dam in a highly ciprofloxacin resistant (CiproR) clinical UPEC isolate bearing multiple common quinolone resistance-conferring mutations (Sup. Table 3). Remarkably, though dam deletion did not restore full sensitivity to this isolate, the ciprofloxacin MIC for CiproR UPEC was reduced by over half, and its MBC90 by 4.6 fold (Fig. 4c). Thus, removing GATC methylation can potentiate antibiotic lethality in both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant pathogenic organisms.

Together, our results define an important structural role for the bacterial epigenome in antibiotic stress survival. Characterization of the adenine methylome revealed highly stable global GATC methylation levels during log-to-stationary phase transition and sub-inhibitory β-lactam stress, and while we identified several previously uncharacterized GATC sites with variable methylation over time, antibiotic stress did not significantly alter these patterns.

Despite the remarkable stability of the GATC methylome, E. coli lacking Dam are hypersensitive to antibiotic stress. Deletion of E. coli dcm or Neisseria meningitides Mod11A (an adenine Mtase) was also reported to alter bacterial sensitivity to toxic compounds, but increased resistance, not hypersensitivity, was observed, and attributed to altered gene expression36,69. While we cannot exclude additional involvement of transcriptional dysregulation, our data suggest that the GATC methylome represents an important backbone structure enabling DNA repair processes to function in the context of β-lactam and quinlone stress. Specifically, GATC methylation likely supports antibiotic-elicited mutagenesis dependent on PolIV, an error-prone polymerase induced transcriptionally or post-translationally in the presence of several antibiotics53–55. In the absence of GATC methylation, MMR machinery can convert post-replicative mismatches to DSBs47, which accumulate to toxic levels in mutagenizing drug-exposed dam-deficient bacteria. In Δdam E. coli, the DNA damage response program (SOS) is constitutively sub-induced65. dinB is within the SOS regulon66,67, thus Δdam E. coli may be primed for rapid PolIV synthesis, enhancing their sensitivity. In addition, DNA breaks caused by MMR in mutating, drug-exposed Δdam bacteria likely promote SOS pathway induction further, leading to more PolIV activity68. Consequently, during antibiotic stress, a toxic feedback loop may establish itself (Fig. 3e). This model is consistent with earlier observations that DNA-damaging agents cause MMR-dependent genotoxicity in Δdam bacteria49,50,69–71; however, our data further suggest that any initial DNA damage caused by antibiotics directly is not sufficient kill Δdam bacteria, as the error-prone PolIV is required for hypersensitivity (Fig. 3a and Sup. Fig. 5a). Measuring mutagenesis rates in Δdam bacteria is challenging (due to MMR toxicity to mutating cells) and we cannot completely exclude a requirement for PolIV in introduction of initial DNA damage. This seems unlikely, however, given that similar levels of damage were recorded in wild-type and ΔdinB bacteria during drug treatment (Fig. 3d). Thus, our data support a model in which antibiotic stress becomes lethal as mutagenic PolIV activity fuels a genotoxic MMR response in the absence of GATC methylation.

Our findings raise the possibility of targeting Dam to enhance the therapeutic activity of existing drugs. Several classes of antibiotics induce mutagenesis at sub-inhibitory concentrations9,12,55,60–62, and may thus be subject to potentiation by this mechanism. While enhancement of drug activity could be harnessed to lower effective therapeutic doses in drug-sensitive infections, it may also allow re-sensitization of resistant organisms. Indeed, our data suggest that targeting Dam methylation can partially reverse ciprofloxacin resistance in UPEC. More broadly, this observation suggests that mutagenic stress responses can occur and be therapeutically exploited in highly drug-resistant pathogenic organisms. In addition to drug potentiation, inhibiting Dam has been proposed as a strategy to weaken bacterial pathogenicity in vivo25,72–74, as GATC methylation controls virulence gene expression in some organisms. While elevated rates of mutagenesis and induction of certain prophages75 in the absence of Dam could complicate a Dam inhibitor-based monotherapy, these drawbacks may be mitigated in the context of combination treatment. In summary, our results suggest that targeting bacterial epigenomic structures that support mutagenic stress responses may be a viable strategy to enhancing antibiotic activity.

Online methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Laboratory bacterial strains used are derived from E. coli K12 (BW25113 obtained from the Coli Genetic Stock Center or MG1655 obtained from ATCC). The uropathogenic E. coli strain UTI89 was kindly provided to us from Matt Conover and Scott Hultgren. The ciprofloxacin-resistant uropathogenic E. coli isolate (UPEC CiproR) was collected from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Specimen bank (Sup. Table 3). Deletion mutants on the BW25113 background were derived from the KEIO collection following KanR cassette removal. Deletion mutants on the MG1655 background were constructed by allelic transduction from KEIO collection strains using classical P1 phage transduction, followed by KanR cassette excision. The dam null phenotype was confirmed by PCR alone or with electrophoresis of genomic DNA digested with DpnII, which cleaves unmethylated GATC sites only. For construction of the Δdam UTI89 and Δdam UPEC CipoR strains, the parent strain bearing a KM208 plasmid-based Red-recombinase system was electroporated with a PCR amplicon encoding the Δdam::KanR allele. Recovered cells were selected for kanamycin-resistant homologous recombinants. The plasmid was cured and the KanR cassette was removed. The genotype of each deletion strain was verified by colony PCR. The plasmid used in the dam complementation studies, namely pZS*31 (Fig. 1c, Sup. Fig. 2), was obtained from Expressys and belongs to the pZ vector family. pZS*31 has a pSC101* origin of replication (which yields a low copy number of 3–5 plasmids per cell) and a chloramphenicol-resistance marker. Genes encoding either Dam (with 500bp upstream flanking region) or GFP were inserted into the multiple cloning site. For complementation experiments using mutated versions of dam, the plasmid containing the dam insert was engineered using either Gibson cloning or site-directed mutagenesis (NEB, Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit). Quinolone resistance-conferring mutations in the CipoR UPEC clinical isolate were identified though whole-genome Illumina sequencing of genomic DNA (PureLinK Pro-96 Genomic Purification Kit; Life Technologies). Libraries were prepared as previously described76. Raw sequencing reads were processed by trimming adapter sequences and discarding reads shorter then 28bp. Processed reads were aligned to the E. coli MG1655 genome using breseq77. The genome alignments were searched for known quinolone resistance-conferring mutations in acrA, acrR, beaS, cpxA, cpxB, envZ, gyrA, gyrB, marA, marR, mdtA, mdtB, mdtC, ompC, ompF, ompR, parC, parE, soxR, soxS and tolC genes and their regulatory regions.

Bacterial kill curves, MBC and MIC determination

For timecourse kill curves and MBC assays, stationary-phase bacterial cultures were diluted at 1:1,000 in 25mLs of LB medium in 250mL baffled flasks. Cultures were grown at 37°C and 200rpm until they reached an OD of ~0.3. Cultures were transferred to 24-well plates at 500 μl per well, or to 96-well plates at a final volume of 150ul per well, and either left untreated or treated with the indicated drugs at specified doses. Plates were sealed using breathable membranes (BreatheEasy, Cat #: BEM-1) and incubated at 37°C and 900rpm for the remainder of the experiment. CFUs were enumerated at desired time points (4 hours for MBC determination) by spot plating 5 μl of ten-fold serially diluted culture onto LB agar and counting colonies after overnight growth at 37°C. Percent survival at each timepoint was calculated in relation to the CFU immediately before treatment (0h). For MIC determination, antibiotics were serially diluted in a 96-well plate and mixed with stationary-phase bacterial cultures diluted at 1:10,000 in a final volume of 150 μl LB per well. OD was measured from plates after 24hrs of growth at 900rpm and 37C.

Genomic DNA extraction and PacBio sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from E. coli K12 MG1655 LB cultures grown in the presence or absence of ampicillin using the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Sigma). To assess genomic methylation status, gDNA extracted from stationary-phase cultures was quantified, digested using DpnII (NEB) and run on an 0.8% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. For methylome analyses, samples were sent to UMass Medical School Deep Sequencing Core, where methylome data were obtained by PacBio Core Enterprise instrument SMRT. SMRTbell™ DNA template libraries for SMRT sequencing were prepared according to the instructions described in the ‘Procedure & Checklist for 10 kb Template Preparation and Sequencing’ document (Pacific Biosciences). Briefly, genomic DNA samples were first sheared to a target shear size of 10kb using g-Tube devices (Covaris, Inc.), treated with DNA damage repair mix, end-repaired and ligated to hairpin adapters. The SMRTbell libraries were prepared using the DNA Template Prep Kit 2.0 (3–10kb) fro Pacific Biosciences. Incompletely formed SMRTbell templates were digested using Exonuclease III (New England Biolabs) and Exonuclease VII (Affymetrix). The prepared SMRTbell libraries were sequenced using a 120-min movie acquisition time and P4 polyerase-C2 DNA sequencing reagent kits following standard instructions for a PacBio RS II instrument (Pacific Biosciences). Each E. coli sample was sequenced on four or more SMRT cells yielding a total of approximately 200-fold double-stranded coverage of the bacterial genome, and two or three biological replicates were sequenced for each antibiotic treatment condition (Sup. Data Set 2). Sequencing coverage was comparable between methylated and non-methylated sites (Sup. Table 1, Sup. Data Set 2), ruling out coverage loss as an explanation for the absence of methylation.

Bioinformatics analyses of SMRT sequencing data

Genome-wide detection of base modification and the affected motifs was performed using the standard (default) settings in the ‘RS_Modification_and_Motif_Analysis.1’ protocol included in SMRT Analysis version 2.3.0 Patch 5. The FASTA reference genome sequence (E. coli K12 MG1655, NCBI NC_000913.2) used for the base modification detection analyses was obtained from Pacific Biosciences. For motif identification, the base modification Quality Value (QV) threshold setting was left at the default value of 30. Interpulse duration (IPD) values were measured for all nucleotide positions in the genome and compared with expected durations in an in silico kinetic model of the polymerase for significant associations. ‘Frac’ values were calculated in SMRT Analysis using a standard mixture model analysis of the pooled kinetic data for a given sample. The frac output value provides information about the fraction of individual molecules displaying a methylation signal at each identified motif site within the genome (Sup. Data Set 1). Methylation frac values were derived from IPD data within the SMRT pipeline using the single site mixture model39. The value 0 was substituted for frac values that were below detection limits. The values from two or three experimental replicates were compared by Student’s T-test and FDR adjusted p-values were obtained by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (Sup. Data Set 1). Circular graphs were generated using the Circos software package

Flow cytometric assessment of DNA damage

E. coli log-phase cultures were transferred to a 96-well plate (200 μl/well) and treated with ampicillin (2.5 μg/mL) or hydrogen peroxide (100mM) for 30 minutes to 2 hours at 37°C and 900rpm. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3,000× g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended vigorously in 200 μl of cold 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes to allow fixation. Bacteria were centrifuged again, then resuspended in 200 μl of cold permeabilization buffer (0.1%TritonX-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate). After 2 minutes at room temperature, bacteria were centrifuged and washed in PBS. After pelleting the cells and discarding the supernatant, cells were resuspended in 50 μl of TUNEL labeling mix (dUTP-FITC and TdT enzyme) or 50 μl TUNEL labeling reagent (dUTP-FITC) according to manufacturer’s instructions (Roche; in situ cell death detection kit, fluorescein). Bacteria were stained for 1h at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 1 μg/mL PI/PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD LSR Fortessa). PI negative cells, which lack genomic material, were excluded from the analysis. Gating was determined using single color and unstained controls as references. For Fig. 3d and statistical analysis, background staining with labeling reagent only was subtracted for each sample to account for treatment dependent shifts in auto-fluorescence or stain retention.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis performed on log10-transformed data (for survival experiments) or on untransformed data (for TUNEL assay) using a two-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc t-test using Sidak’s multiple comparison test correction. In all cases, p-values indicated are multiplicity adjusted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Ferrante, Ewen Cameron, Kyle Allison, Jonathan Winkler, Jeff Way, Charley Gruber, Prerna Bhargava, Michio Painter, Nawang Sherpa, Tami Lieberman, Laura Certain and Yoshikazu Furuta for critical feedback and technical support over the course of this study. We also thank Matt Conover and Scott Hultgren for generously providing the UTI89 strain, as well as related reagents and protocols. Additionally, we are grateful for SMRT sequencing support from Maria Zapp and Ellie Kittler at the UMassMed Sequencing core, and from Sonny Mark, Khai Luong, Michael Weiand and Onureena Banerjee at Pacific Biosciences. This work was supported by funding from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency grant HDTRA1-15-1-0051, the National Institutes of Health grant 1U54GM114838-01, the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine and Donors Cure Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health and Research, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Author contributions

N. R. C. conceived of project, designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; C. A. R. performed bioinformatics analyses. S. J. performed experiments; R. S. S. performed experiments and bioinformatics analyses; A. G. contributed intellectually to the project and helped design experiments; P. B. contributed intellectually to the project; H. L. performed bioinformatics analyses and provided mentorship; J. J. C. oversaw the project and provided mentorship.

References

- 1.Antimicrobial Resistance Global Surveillance Report. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, et al. Targeting a bacterial stress response to enhance antibiotic action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14570–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903619106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu TK, Collins JJ. Engineered bacteriophage targeting gene networks as adjuvants for antibiotic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4629–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800442106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wigle TJ, et al. Inhibitors of RecA activity discovered by high-throughput screening: cell-permeable small molecules attenuate the SOS response in Escherichia coli. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:1092–101. doi: 10.1177/1087057109342126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brynildsen MP, Winkler JA, Spina CS, MacDonald IC, Collins JJ. Potentiating antibacterial activity by predictably enhancing endogenous microbial ROS production. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:160–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2069–89. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wexselblatt E, et al. Relacin, a novel antibacterial agent targeting the Stringent Response. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002925. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant SS, Kaufmann BB, Chand NS, Haseley N, Hung DT. Eradication of bacterial persisters with antibiotic-generated hydroxyl radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12147–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203735109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller C, et al. SOS response induction by beta-lactams and bacterial defense against antibiotic lethality. Science. 2004;305:1629–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1101630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw KJ, et al. Comparison of the changes in global gene expression of Escherichia coli induced by four bactericidal agents. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;5:105–22. doi: 10.1159/000069981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaldalu N, Mei R, Lewis K. Killing by ampicillin and ofloxacin induces overlapping changes in Escherichia coli transcription profile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:890–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.890-896.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh EB, et al. Transcriptional modulation of bacterial gene expression by subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17025–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252607699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mesak LR, Miao V, Davies J. Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on SOS and DNA repair gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3394–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01599-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laureti L, Matic I, Gutierrez A. Bacterial Responses and Genome Instability Induced by Subinhibitory Concentrations of Antibiotics. Antibiotics. 2013;2:100–114. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole K. Stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:227–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sexton JZ, et al. Novel Inhibitors of E. coli RecA ATPase Activity. Curr Chem Genomics. 2010;4:34–42. doi: 10.2174/1875397301004010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwyer DJ, et al. Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2100–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401876111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kultz D. Evolution of the cellular stress proteome: from monophyletic origin to ubiquitous function. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:3119–24. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeder EA, Raimundo N, Shadel GS. Epigenetic silencing mediates mitochondria stress-induced longevity. Cell Metab. 2013;17:954–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinnusamy V, Zhu JK. Epigenetic regulation of stress responses in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weaver IC, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–54. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Provencal N, Booij L, Tremblay RE. The developmental origins of chronic physical aggression: biological pathways triggered by early life adversity. J Exp Biol. 2015;218:123–133. doi: 10.1242/jeb.111401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casadesus J, Low D. Epigenetic gene regulation in the bacterial world. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:830–56. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinus MG, Casadesus J. Roles of DNA adenine methylation in host-pathogen interactions: mismatch repair, transcriptional regulation, and more. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:488–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasu K, Nagaraja V. Diverse functions of restriction-modification systems in addition to cellular defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:53–72. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00044-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casadesus J, Low DA. Programmed heterogeneity: epigenetic mechanisms in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13929–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.472274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srikhanta YN, et al. Phasevarions mediate random switching of gene expression in pathogenic Neisseria. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000400. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camacho EM, Casadesus J. Regulation of traJ transcription in the Salmonella virulence plasmid by strand-specific DNA adenine hemimethylation. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1700–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camacho EM, et al. Regulation of finP transcription by DNA adenine methylation in the virulence plasmid of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5691–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5691-5699.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunet YR, Bernard CS, Gavioli M, Lloubes R, Cascales E. An epigenetic switch involving overlapping fur and DNA methylation optimizes expression of a type VI secretion gene cluster. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernday AD, Braaten BA, Low DA. The mechanism by which DNA adenine methylase and PapI activate the pap epigenetic switch. Mol Cell. 2003;12:947–57. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis BM, Chao MC, Waldor MK. Entering the era of bacterial epigenomics with single molecule real time DNA sequencing. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang G, et al. Genome-wide mapping of methylated adenine residues in pathogenic Escherichia coli using single-molecule real-time sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1232–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flusberg BA, et al. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat Methods. 2010;7:461–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blow MJ, et al. The Epigenomic Landscape of Prokaryotes. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horton JR, Zhang X, Blumenthal RM, Cheng X. Structures of Escherichia coli DNA adenine methyltransferase (Dam) in complex with a non-GATC sequence: potential implications for methylation-independent transcriptional repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:4296–308. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guyot JB, Grassi J, Hahn U, Guschlbauer W. The role of the preserved sequences of Dam methylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3183–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schadt EE, et al. Modeling kinetic rate variation in third generation DNA sequencing data to detect putative modifications to DNA bases. Genome Res. 2013;23:129–41. doi: 10.1101/gr.136739.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urig S, et al. The Escherichia coli dam DNA methyltransferase modifies DNA in a highly processive reaction. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:1085–96. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tavazoie S, Church GM. Quantitative whole-genome analysis of DNA-protein interactions by in vivo methylase protection in E. coli. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:566–71. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang MX, Church GM. A whole genome approach to in vivo DNA-protein interactions in E. coli. Nature. 1992;360:606–10. doi: 10.1038/360606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holst B, Sogaard-Andersen L, Pedersen H, Valentin-Hansen P. The cAMP-CRP/CytR nucleoprotein complex in Escherichia coli: two pairs of closely linked binding sites for the cAMP-CRP activator complex are involved in combinatorial regulation of the cdd promoter. EMBO J. 1992;11:3635–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hale WB, van der Woude MW, Low DA. Analysis of nonmethylated GATC sites in the Escherichia coli chromosome and identification of sites that are differentially methylated in response to environmental stimuli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3438–41. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3438-3441.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lobner-Olesen A, Skovgaard O, Marinus MG. Dam methylation: coordinating cellular processes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA mismatch repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doutriaux MP, Wagner R, Radman M. Mismatch-stimulated killing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2576–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marinus MG. Recombination is essential for viability of an Escherichia coli dam (DNA adenine methyltransferase) mutant. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:463–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.463-468.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fram RJ, Cusick PS, Wilson JM, Marinus MG. Mismatch repair of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)-induced DNA damage. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;28:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karran P, Marinus MG. Mismatch correction at O6-methylguanine residues in E. coli DNA. Nature. 1982;296:868–9. doi: 10.1038/296868a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marinus MG. DNA methylation and mutator genes in Escherichia coli K-12. Mutat Res. 2010;705:71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fijalkowska IJ, Schaaper RM, Jonczyk P. DNA replication fidelity in Escherichia coli: a multi-DNA polymerase affair. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:1105–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galhardo RS, Hastings PJ, Rosenberg SM. Mutation as a stress response and the regulation of evolvability. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:399–435. doi: 10.1080/10409230701648502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Capilla T, et al. SOS-independent induction of dinB transcription by beta-lactam-mediated inhibition of cell wall synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1515–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1515-1518.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutierrez A, et al. beta-Lactam antibiotics promote bacterial mutagenesis via an RpoS-mediated reduction in replication fidelity. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1610. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rohwer F, Azam F. Detection of DNA damage in prokaryotes by terminal deoxyribonucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1001–6. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.1001-1006.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKelvie JC, et al. Inhibition of Yersinia pestis DNA adenine methyltransferase in vitro by a stibonic acid compound: identification of a potential novel class of antimicrobial agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:172–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hobley G, et al. Development of rationally designed DNA N6 adenine methyltransferase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:3079–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mashhoon N, Pruss C, Carroll M, Johnson PH, Reich NO. Selective inhibitors of bacterial DNA adenine methyltransferases. J Biomol Screen. 2006;11:497–510. doi: 10.1177/1087057106287933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kohanski MA, DePristo MA, Collins JJ. Sublethal antibiotic treatment leads to multidrug resistance via radical-induced mutagenesis. Mol Cell. 2010;37:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baharoglu Z, Mazel D. Vibrio cholerae triggers SOS and mutagenesis in response to a wide range of antibiotics: a route towards multiresistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2438–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01549-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ysern P, et al. Induction of SOS genes in Escherichia coli and mutagenesis in Salmonella typhimurium by fluoroquinolones. Mutagenesis. 1990;5:63–6. doi: 10.1093/mutage/5.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen SL, et al. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5977–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marino Sabo E, Stern JJ. Approach to antimicrobial prophylaxis for urology procedures in the era of increasing fluoroquinolone resistance. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:380–6. doi: 10.1177/1060028013517661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peterson KR, Wertman KF, Mount DW, Marinus MG. Viability of Escherichia coli K-12 DNA adenine methylase (dam) mutants requires increased expression of specific genes in the SOS regulon. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:14–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00397979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2001;158:41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galhardo RS, et al. DinB upregulation is the sole role of the SOS response in stress-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2009;182:55–68. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.100735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tippin B, Pham P, Goodman MF. Error-prone replication for better or worse. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:288–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prieto AI, Ramos-Morales F, Casadesus J. Bile-induced DNA damage in Salmonella enterica. Genetics. 2004;168:1787–94. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wyrzykowski J, Volkert MR. The Escherichia coli methyl-directed mismatch repair system repairs base pairs containing oxidative lesions. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1701–4. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1701-1704.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bale A, d’Alarcao M, Marinus MG. Characterization of DNA adenine methylation mutants of Escherichia coli K12. Mutat Res. 1979;59:157–65. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(79)90153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heithoff DM, Sinsheimer RL, Low DA, Mahan MJ. An essential role for DNA adenine methylation in bacterial virulence. Science. 1999;284:967–70. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5416.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pucciarelli MG, Prieto AI, Casadesus J, Garcia-del Portillo F. Envelope instability in DNA adenine methylase mutants of Salmonella enterica. Microbiology. 2002;148:1171–82. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garcia-Del Portillo F, Pucciarelli MG, Casadesus J. DNA adenine methylase mutants of Salmonella typhimurium show defects in protein secretion, cell invasion, and M cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11578–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murphy KC, Ritchie JM, Waldor MK, Lobner-Olesen A, Marinus MG. Dam methyltransferase is required for stable lysogeny of the Shiga toxin (Stx2)-encoding bacteriophage 933W of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:438–41. doi: 10.1128/JB.01373-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baym M, et al. Inexpensive multiplexed library preparation for megabase-sized genomes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barrick JE, et al. Identifying structural variation in haploid microbial genomes from short-read resequencing data using breseq. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1039. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baym M, et al. Inexpensive multiplexed library preparation for megabase-sized genomes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barrick JE, et al. Identifying structural variation in haploid microbial genomes from short-read resequencing data using breseq. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1039. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.