Abstract

This review presents synthesis and chemistry of nucleoside analogs, possessing an additional fused, heterocyclic ring of the “etheno” type, such as 1,N6-ethenoadenosine, 1,N4-ethenocytidine, 1,N2-ethenoguanosine, and other related derivatives. Formation of ethenonucleosides, in the presence of α-halocarbonyl reagents and their mechanism, stability, and degradation, reactions of substitution and transglycosylation, as well as their application in the nucleoside synthesis, have been described. Some of the discussed compounds may be applied as chemotherapeutic agents in antiviral and anticancer treatment, acting as pro-nucleosides of already known, biologically active nucleoside analogs.

Keywords: nucleoside analogs, ethenonucleosides, wyosine, fused heterocycles, tricyclic acyclovir, antiviral activity

Introduction

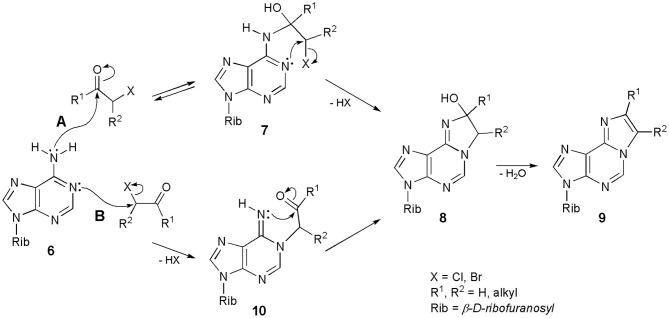

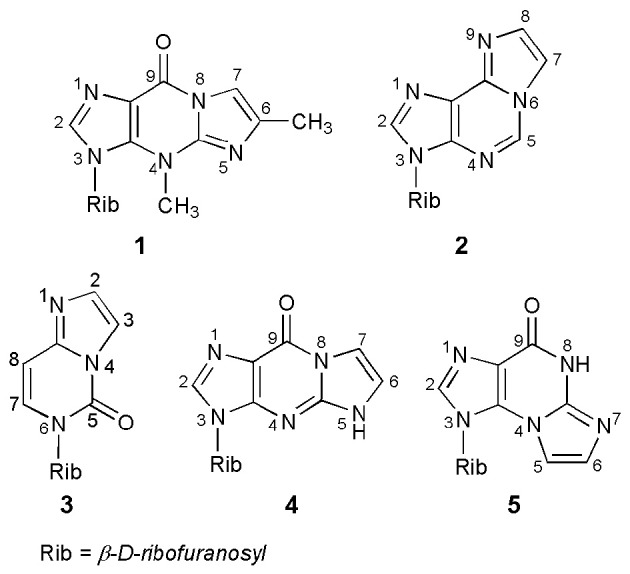

A number of base-modified nucleosides demonstrate significant biological properties, acting, among others, as antiviral or antitumor agents. One of the possible modifications of the nucleoside is their transformation into ethenonucleosides. Thus, nucleosides or their respective heterocyclic bases, possessing an exocyclic amino group, as well as a neighboring endocyclic nitrogen, can react with some bifunctional reagents (e.g., α-halocarbonyl compounds) to form products with an additional five-membered ring of the imidazole type. The ethenonucleosides basically do not occur in nature; the only exception here are Y-nucleosides, strongly fluorescent tricyclic derivatives of guanosine, occurring in the anticodon loop of some phenylalanine transfer ribonucleic acids (tRNAPhe; Blobstein et al., 1975; Kasai et al., 1976). Wyosine, i.e., 3-methyl-1,N2-(prop-1-ene-1,2-diyl)guanosine (compound 1; Figure 1), is the simplest example of the Y-nucleosides family. The other known ethenonucleosides, such as 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2), 1,N4-ethenocytidine (3), 1,N2-ethenoguanosine (4), or N2,3-ethenoguanosine (5), have been obtained via chemical modification of parent ribonucleosides.

Figure 1.

Naturally occurring wyosine (1) and synthetic ethenonucleosides.

In the following review, we drew our attention mainly to chemistry of ethenonucleosides and related compounds. Their biological properties, fluorescence study, antiviral action, and mutagenic effect on the nucleic acid level have already been presented in other reviews or recent articles (e.g., Secrist et al., 1972; Steiner et al., 1973; Kusmierek and Singer, 1992; Golankiewicz and Ostrowski, 2006; De Clercq, 2010; Gómez-Bombarelli et al., 2011; Jahnz-Wechmann et al., 2015). Therefore, in this review, we will focus on the chemical properties of ethenonucleosides, barely mentioning or shortly discussing their other features.

Synthesis

Derivatives of adenosine and cytidine

The first ever synthesis of ethenonucleosides, a new class of chemically modified components of nucleic acids, was reported in the 1970's. Thus, treatment of 9-methyladenine and 1-methylcytidine with chloroacetaldehyde (CAA), and using them as models for appropriate nucleosides, gave previously unknown fluorescent bases (Kochetkov et al., 1971). In turn, a similar reaction of adenosine and cytidine allowed to obtain the respective nucleosidic products—1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2) and 1,N4-ethenocytidine (3; Secrist et al., 1972). The optimum pH value for this reaction was established at 3.5 for cytosine, and 4.5 for adenosine (Kochetkov et al., 1971; Barrio et al., 1972;). The yield of the synthesis usually varied from satisfactory to quantitative. They also showed that another, naturally occurring nucleoside–guanosine, fulfilled the structural requirements to form its etheno derivative, however it practically did not react with aq. chloroacetaldehyde (Barrio et al., 1972).

Since that time, a great number of etheno products derived from adenosine or cytidine have been reported (e.g., Steiner et al., 1973; Barrio et al., 1976; Kost and Ivanov, 1980; Sattsangi et al., 1980; Leonard, 1984; Kifli et al., 2004). It has also been shown that not only haloaldehydes and haloketones may be applied in the synthesis of etheno derivatives of A and C. Other reagents of a similar nature are: bromomalonaldehyde (Nair et al., 1984), N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-2-bromoacetamide and 2-chloroketenene diethyl acetal (Leonard and Cruickshank, 1985), malonaldehyde (Seto et al., 1985), epoxy carbonyl compounds (Nair and Offerman, 1985), 1-halooxiranes (Guengerich and Raney, 1992), 1,2-dicarbonyl reagents (Shapiro and Hachmann, 1966) mucochloric acid (Mäki et al., 1999), or 3-chloropropyne (Virta et al., 2003). Quite recently, Xie et al. (2014) have reported synthesis of etheno adenosines and cytidines, via a copper-catalyzed domino Michael oxidative cross-coupling, with nitroolefins.

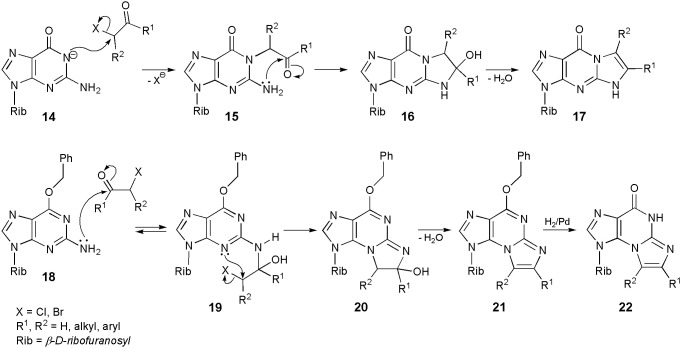

Interestingly, after decades of synthesizing ethenonucleosides with the use of α-halocarbonyl reagents, the mechanism of their formation still remains unclear. Regioselectivity of the reaction is not controversial: carbonyl group of CAA reacts with the exocyclic amino group of nucleosides, while chloromethylene portion alkylates the endocyclic nitrogen. This has been demonstrated in the reaction with α-haloketones, possessing an additional alkyl substituent, i.e., α-bromopropionaldehyde and chloroacetone (Krzyzosiak et al., 1983), or with the use of deuterium-labeled reagents (Kost and Ivanov, 1980). However, the sequence of events in the formation of etheno rings is not obvious in the majority of cases. Biernat et al. (1978) and Krzyzosiak et al. (1983) postulated an initial condensation of carbonyl group of the α-halocarbonyl reagents and exocyclic 6-amino group of adenosine (6; Scheme 1: mechanism A), leading to an unstable intermediate (7). The reaction is reversible. Intermediate 7 then undergoes intramolecular cyclization to a stable intermediate 8, as the result of alkylation of endocyclic N1, and this process is irreversible. Compound 8 may now undergo dehydration to the final 1,N6-etheno product (9). The intermediate product 8 has been isolated, and its structure confirmed by the 1H NMR data (Biernat et al., 1978).

Scheme 1.

Two possible mechanisms of synthesis of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine and its derivatives.

Another, equally convincing pathway of synthesis is presented in Scheme 1; mechanism B. Adenosine (6) is initially alkylated at the N1-position to furnish an intermediate product (10). This step is irreversible, because the N-C bond in 1-alkyladenines is very stable. However, compound 10 immediately undergoes a ring-closure reaction, to produce compound 8 and again, 8 is converted to 9 in the dehydration step. Considering the sequence of events in the formation of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2) and its derivatives (general structure 9), we generally agree with the previous assumption of Kost and Ivanov (1980) that both mechanisms may take place, depending on the structure of α-halocarbonyl reagent, applied in this transformation. Thus, haloaldehydes and chloroacetaldehyde in particular, can react according to the pathway A, while haloketones and 1-halooxiranes (Guengerich and Raney, 1992) would rather react in line with the mechanism B. In our opinion, the structure of the starting adenosine precursor has very little or no effect on the discussed process. The structure of substrate, however, will have a deciding effect in the synthesis of ethenoguanosines (see Chapter Derivatives of Guanosine).

The mechanisms presented in Scheme 1 apply to the synthesis of 1,N4-ethenocytidine (3) as well. Other N-alkyl nucleosides derived from A and C may also react with CAA, e.g., N6-isopentenyladenosine (i6A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), or N4-methylcytosine (Barrio et al., 1972; Biernat et al., 1978; Sattsangi et al., 1980). Because of the presence of additional N-alkyl group, the reaction intermediates of the type 8 cannot be dehydrated to fluorescent etheno compounds, and the reaction stops at this stage. Other alkylated substrates, like 1-metyladenosine (m1A) or 3-metylcytidine (m3Cyt), do not react with CAA and related reagents, due to the absence of amidine system in their structures (Barrio et al., 1972).

Derivatives of guanosine

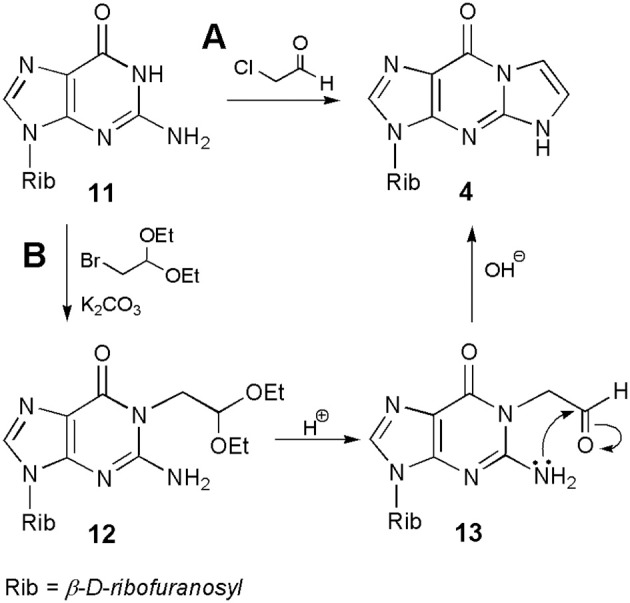

Much of the discussion so far concerned the synthesis of ethenonucleosides derived from adenosine and cytidine. As stated above, guanosine (11; Scheme 2) is almost unreactive under conditions suitable for modification of A and C, and therefore this nucleoside gained relatively less attention in the beginning. However, as shown in subsequent years, ethenoguanosine and its derivatives deserve special attention due to their biological properties and usefulness in nucleoside chemistry. Because of its structure, guanosine can form two isomeric nucleosides, 1,N2-ethenoguanosine (4), called “linear” form, and “angular” N2,3-etheno compound (5). The former compound may be obtained from guanosine under treatment with chloroacetaldehyde, nevertheless the yield is usually very poor, e.g., 7.5% at pH 6.4 after 7 days (Sattsangi et al., 1977). The yield of 4 can be improved at higher pH values, e.g., 13% at pH 9–10, or under anhydrous conditions, by using sodium salt of guanosine prepared in DMSO and 90% ethereal solution of CAA (yield 24%; Boryski, 1990). However, the best yield of the synthesis may be obtained in a two-step procedure. As shown in Scheme 2, alkylation of guanosine (11), with bromoacetaldehyde diethyl acetal in the presence of potassium carbonate, leads to the 1-substituted derivative (12; O6-isomers are usually reaction side-products), which gives an unstable aldehyde intermediates, upon acidic hydrolysis (13). The latter compound (corresponding to compound 10 in the synthesis of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine) undergoes a spontaneous intramolecular cyclization and dehydration to 1,N2-ethenoguanosine (4; overall yield 50%; Boryski, 1990; Boryski et al., 1991). In turn, another compound of this type, a 6-hydroxymethyl derivative of 1,N2-ethenoguanosine may be obtained in the reaction of guanosine with glycidaldehyde (Nair and Turner, 1984). More recently, it has been shown that a linear ethenoguanosine analog can be synthesized in a satisfactory yield (54%), when applying CAA and 6-chloro-2-aminopurine substrates at 70°C (Horejsi et al., 2006).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 1,N2-ethenoguanosine.

The reactions of guanosine with substituted haloketones are much easier to perform than in the case of chloroacetaldehyde. In a typical procedure (Scheme 3), guanosine is converted to its sodium salt (14), which is readily alkylated with haloketones to an unstable intermediate (15). Intramolecular cyclization to 16, followed by dehydration (usually in alkaline media) results in the formation of a linear tricyclic product (general structure 17; yield 70–90%; Kasai et al., 1976; Golankiewicz and Folkman, 1983). Consequently, the sequence of events is obvious in this case: the initial 1-alkylation is followed by condensation of carbonyl group and precipitation of exocyclic amine residue. However, O6-substiution dramatically changes the course of reaction. For example, treatment of O6-benzylguanosine with chloroaldehyde gives the angular N2,3-ethenoguanosine (5; Sattsangi et al., 1977; Kusmierek et al., 1987, 1989). Our proposed mechanism for this modification is depicted in Scheme 3. It is well-known that 3-alkylguanosines may never be obtained by direct intermolecular alkylation, and therefore O6-benzylguanosine (18) cannot be alkylated with CAA at the 3-position. Instead of that, 18 undergoes an initial condensation with carbonyl group of the aldehyde, what leads to an unstable intermediate (19). This process is perhaps reversible, but compound 19 may undergo an intramolecular 3-alkylation as well, forming the tricyclic product (20). After dehydration to compound 21, the O-benzyl substituent can be removed by applying catalytic hydrogenolysis to obtain the final product (general structure 22; R1,R2 = H for 5). Quite similar results were reported in the case of O6-ethylguanosine (Kusmierek et al., 1987).

Scheme 3.

Mechanisms of synthesis of 1,N2-ethenoguanosine, N2,3-ethenoguanosine and their derivatives.

In line with the proposed mechanism, guanosine residue in nucleic acids should be modified by CAA to the linear 1,N2-ethenoguanosine (4). On the other hand, treatment of nucleic acids with vinyl chloride gave, among other ethenonucleosides, the fluorescent angular product—N2,3-ethenoguanosine (5). It should be noted at this point that vinyl chloride, a strong carcinogen, is metabolized in vivo to chloroacetaldehyde, which reacts with nucleobases. (Kusmierek et al., 1987; Singer et al., 1987). The formation of 5 can be rationalized in the following way: guanosine, participating in the base pairing of double helix, may exist in a tautomeric form, other than that of the free nucleoside, i.e., O6=C–N1H → HO6–C=N1. The structure of the second tautomer corresponds to that of the O6-alkylguanosine, and this is why N2,3-ethenoguanosine is formed at the nucleic acid level.

Other ethenonucleosides

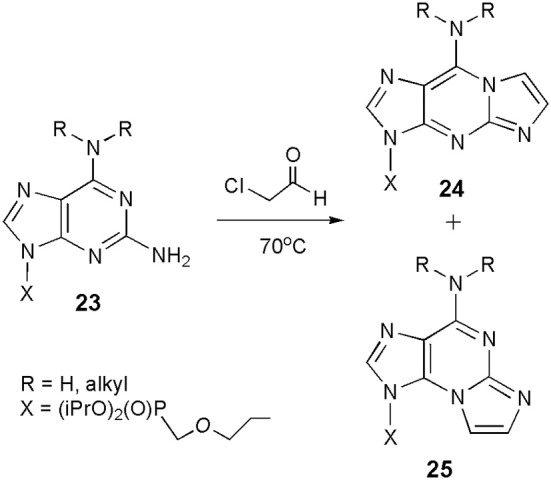

Compounds related to both forms of ethenoguanosine may also be synthesized in the reaction of CAA with 2,6-diaminopurine nucleosides (general structure 23; Scheme 4), which are considerably more reactive than guanosine (Horejsi et al., 2006). Interestingly, the reaction leads to a mixture of linear (24) and angular (25) products. Their ratio clearly depends on substitution in the N6-position. As reported, unsubstituted substrate (R=H, H) gave a 1:3 mixture of 24 and 25, N6-cyclopropyl derivative was exclusively transformed to the linear product (24), whereas modification of N6,N6-diethyl compound yielded only the angular isomer (25). So far, we cannot find any rational explanation for those unexpected results. Moreover, 2,6-diaminopurine nucleosides may be considered as analogs of both adenosine and guanosine, and if so, one could expect rather the formation of products structurally related to 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2).

Scheme 4.

Formation of the etheno products in the reaction of 2,6-diaminopurine nucleosides with CAA.

However, in general, the synthesis of ethenonucleosides proceeds with high selectivity. The sugar moiety has no substantial effect on the course and yield of this modification. Therefore, the etheno derivatives can be obtained from a variety of protected and unprotected substrates, including e.g., ribo- and deoxyribonucleosides, arabinofuranosides, acyclonucleosides, their phosphates, cyclic phosphates and polynucleotide chains of RNA and DNA.

Chemistry

As far as the sugar portion is concerned, ethenonucleosides are quite similar in their reactivity to other nucleosides. Therefore, in the present review we shall focus our attention on reactions involving the aglycon moiety of these etheno-bidged compounds and their derivatives.

Alkylation

Some intensive studies on alkylation of ethenonucleosides have been performed in the case of guanosine derivatives. The reason for that was a close structural similarity of 1,N2-ethenoguanosine (4) and the simplest Y-nucleoside, wyosine (1). Therefore, a direct methylation in the 4-position of the tricylic etheno compound would give rise to a straightforward synthesis of the fluorescent Y-nucleosides, avoiding a laborious, multi-step procedure via 3-methylguanosine, elaborated by Itaya et al. (1980).

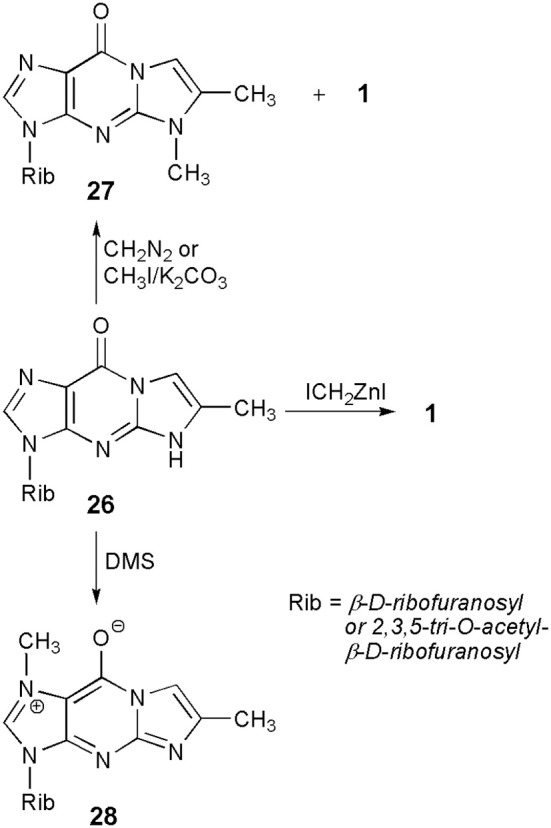

A common substrate for the methylation study—4-desmethylwyosine (i.e., 6-methyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine; compound 26 in Scheme 5), may easily be obtained by treatment of guanosine (6) with bromoacetone (Kasai et al., 1976). Depending on the reaction conditions, the tricyclic system of 26 may be methylated in different positions. Thus, reaction with diazomethane (Kasai et al., 1976) or with methyl iodide, in the presence of potassium carbonate (Boryski and Ueda, 1985), leads to the 5-methyl product (27), a non-fluorescent isomer of wyosine. In turn, reaction with dimethyl sulfate (DMS) provides fluorescent 1,6-dimethyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine (28), a tricyclic analog of 7-methylguanosine (Golankiewicz and Folkman, 1983). However, the same author, having carefully investigated the methylation of 26 triacetate with diazomethane, demonstrated that triacetate of 1 is formed as a minor product (3%) of this reaction, occurring in addition to predominant amounts of the 5-methyl product (27). However, a major breakthrough on the way to Y-nucleosides was the application of the Simmons-Smith organozinc reagent, ICH2ZnI (Bazin et al., 1987), which effectively transforms the 4-desmethylwyosine system (26) into wyosine (1; yield ca. 70%).

Scheme 5.

Methylation of 4-desmethylwyosine.

Besides N-alkylation reactions, some derivatives of 4-desmethylwyosine (26) undergo an unexpected C-7-aralkylation, as reported by Zeidler and Golankiewicz (1998), and Ostrowski et al. (2000, 2005). The aforementioned reaction takes place when a bulky substituent (e.g., phenyl) is present in the 6-position of substrates, and alkyl halides capable to form stable carbocations, like triphenylmethyl chloride or benzyl bromide, are applied.

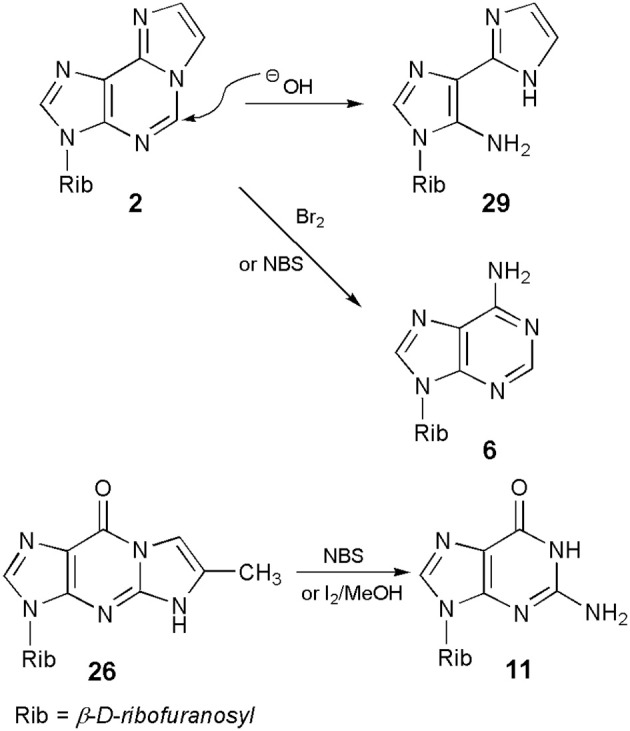

Ring-opening reactions

In general, ethenonucleosides are not very stable chemical species. It is evident in the case of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2), which upon treatment with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide at room temperature, is almost quantitatively transformed into a pyrimidine ring-opened compound, 3-β-d-ribofuranosyl-4-amino-(5-imidazo-2-yl)-imidazole (29; Scheme 6; Yip and Tsou, 1973). No mechanism has been proposed for this ring-opening reaction, but one may assume that it could be an initial nucleophilic attack of hydroxide anion at C5, followed by hydrolysis to 29. The reaction is perhaps closely related to the well-known Dimroth rearrangement of adenine nucleosides. In turn, the additional etheno ring of 2 and its derivatives may be cleaved on bromination with Br2 or with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS), providing in this way a starting adenine nucleoside (Yamaji et al., 1977). To elucidate the reaction mechanism, the authors postulated a complicated sequence of events, with an initial bromination at either 7- and/or 8-position, and the final hydrolysis of brominated intermediates.

Scheme 6.

Ring-opening reactions of ethenonucleosides.

A similar removal of the etheno ring, under oxidizing condition, has been observed in the case of the linear 5-methyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine (26) and its derivatives (Boryski and Ueda, 1985; Boryski et al., 1988a, 1996). Thus, treatment of ethenonucleosides of the general type 17 (including 26) with NBS or iodine in methanol, followed by alkaline hydrolysis, provides the corresponding guanine nucleosides (type 11) in good yields. We have not find any report on an analogous reaction of the angular N2,3-etheno compound (5), but a similar process of removing of the etheno bridge seems to be quite possible in that case.

Interestingly, the stability of 1,N2-ethenoguanosine derivatives depends on the kind of substituents in the 6-position. As shown by Amblard et al. (2009), there is a correlation between the stability and end electron effects of 6-aryl substituents in tricyclic nucleosides related to the linear ethenoguanosine. For example, a 6-(4-dialkylamino)phenyl acyclonucleoside undergoes fast decomposition in water, at room temperature (τ1/2 25 min).

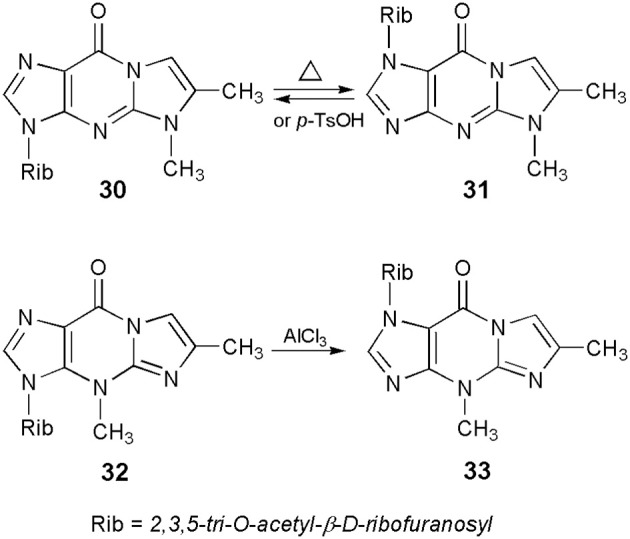

Transglycosylation reactions

Protected nucleosides, derived from the linear 1,N2-ethenoguanosine, like other 6-oxopurine nucleosides (Boryski, 2008), readily undergo transglycosylation reactions, i.e., a transfer of the sugar residue from one nitrogen atom to another. For example, crystalline 5,6-dimethyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine triacetate (or 5-methyl-4-desmethylwyosine triacetate; compound 30 in Scheme 7), when heated without solvents at 200–230°C for a short period of time (5–10 min), isomerizes to a fluorescent 1-(2,3,5-tri-O-acetyl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl compound (31; Boryski, 1996). Similar results are observed in solvents, in the presence of acidic catalysts, e.g., boiling chlorobenzene and p-toluenesulfonic acid. The reaction is fully reversible—no matter which isomer (30 or 31) is used as a substrate, transglycosylation provides an almost equimolar mixture of both compounds (the 3-glycosyl isomer is usually slightly prevailing). In turn, wyosine triacetate (32) undergoes an irreversible isomerization to the corresponding 1-riboside (33), under very mild conditions (methylene chloride, 0°C, AlCl3 as a catalyst; Glemarec et al., 1988). This fact clearly reflects an unusual instability of the N-glycosidic bond in Y-nucleosides (Blobstein et al., 1975; Kasai et al., 1976).

Scheme 7.

Transglycosylation reactions of 5- and 4-methyl ethenoguanosines.

Besides 1,N2-ethenoguanosine derivatives, the angular N2,3-ethenoguanosine nucleosides may probably undergo transglycosylation reactions, since they can be considered as 6-oxopurine nucleosides, but so far this has not been proven experimentally. Glycosyl migration reactions of other ethenonucleosides, derived from adenosine or cytidine, have not been reported in the literature.

Application of etheno compounds

Since their discovery in the 1970's, ethenocleosides found a variety of applications in the structural studies of macromolecules, such as nucleic acids and proteins. Due to their fluorescence, 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2) and 1,N4-ethenocytidine (3), as well as their 2′-deoxy and other derivatives, were applied as versatile probes to investigate mechanisms of enzymatic reaction and three-dimensional structure of RNAs and DNAs. Those rather historical applications have been described or reviewed in many papers (e.g., Secrist et al., 1972; Barrio et al., 1972; Steiner et al., 1973; Schulman and Pelka, 1976; Kost and Ivanov, 1980; Leonard, 1984). The formation of ethenonucleosides at the polynucleotide level has also been intensively studied for better understanding of the toxic influence of carcinogens on nucleic acids, and the mechanism of mutagenesis (e.g., Singer et al., 1987; Kusmierek and Singer, 1992; Golding et al., 1996; Gómez-Bombarelli et al., 2011; Bonnac et al., 2013; Calabretta and Leumann, 2013; Ogawa et al., 2013).

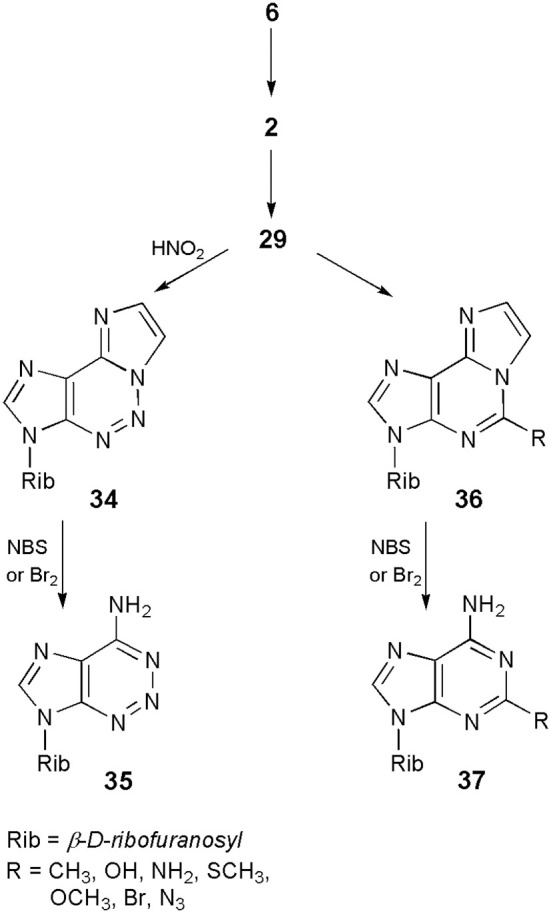

On the other hand, what may turn out to be more beneficial for nucleoside chemists, the ethenonucleosides have found applications as useful synthons in obtaining a number of nucleoside analogs. The approach takes advantage of the fact that etheno modified compounds undergo different reactions than their parent nucleosides (vide ante). Thus, as shown in Scheme 8, adenosine (6), upon treatment with CAA, can easily be transformed into 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (2), which then undergoes a pyrimidine ring-opening reaction in 0.1 N sodium hydroxide to form 3-β-D-ribofuranosyl-4-amino-(5-imidazo-2-yl)-imidazole (29). The latter compound, treated with sodium nitrite in acetic acid, may be converted to a 5-aza analog of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (34; Yip and Tsou, 1973). Finally, removal of the etheno ring on bromination with bromine or NBS produces 2-azaadenosine (35), in good overall yield (Yamaji and Kato, 1975). A similar sequence of ring-opening–ring-closure reactions has been applied by Yamaji et al. (1976, 1977), for the synthesis of a series of 5-substituted derivatives of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine (36), followed by deblocking to the respective 2-substituted adenosines (general structure 37). An analogous approach however, would be useless in the case of 1,N4-ethenocytidine, due to the reactivity of its C7=C8 double bond, under bromination conditions.

Scheme 8.

Application of 1,N6-ethenoadenosine in the synthesis of 2-azaadenosine an 2-subtituted adenosine derivatives.

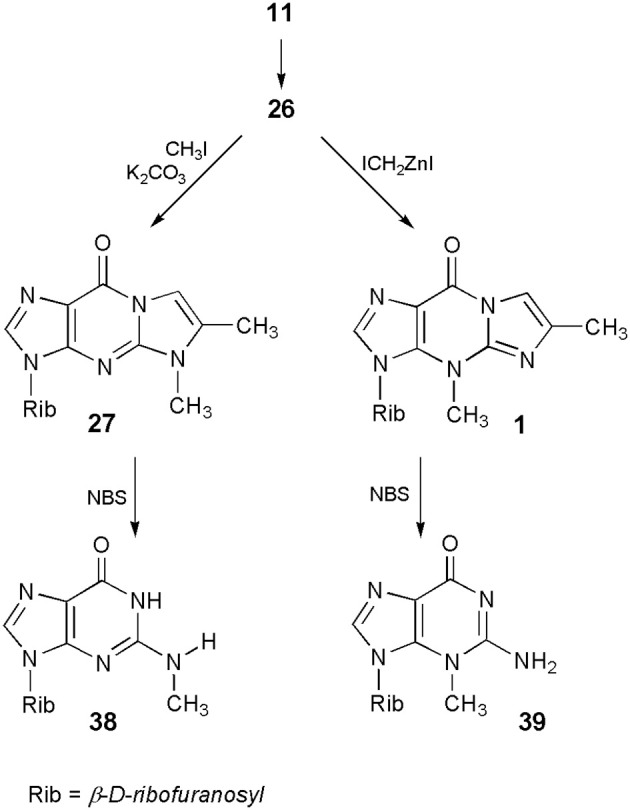

In turn, application of 6-methyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine (26) makes it possible to perform the synthesis of either N2-methyl- or 3-methylguanosine, which cannot be obtained by direct methylation of the parent nucleoside. As presented in Scheme 9, guanosine (11) can be transformed into its tricylic derivatives (26) which, depending on the methylating reagent (vide ante) may give either 5-methyl (27) or 4-methyl (1) isomeric products. In the final step, deblocking of 27 with the use of NBS leads to N2-methylguanosine (38; Boryski and Ueda, 1985), while removal of the etheno ring, in the case of 4-methyl nucleoside (1), gives 3-methylguanosine (39; Boryski et al., 1988a).

Scheme 9.

Application of 4-desmethylwyosine in the synthesis of N2- and 3-methylguanosine.

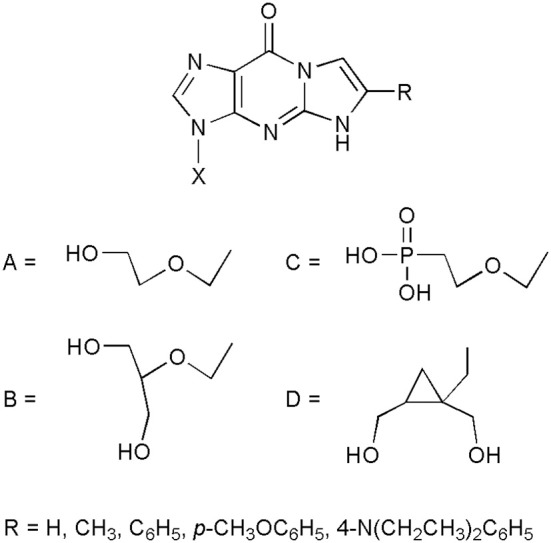

But perhaps the most spectacular application of etheno compounds has been found while searching for new antiviral nucleoside analogs. It has been demonstrated that a potent antiviral drug, acyclovir (ACV; Zovirax; 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine; Elion et al., 1977) retains its antiherpetic activity after chemical modification of the 1,N2-etheno type (Boryski et al., 1988b, 1991). Some selected examples of bioactive ethenoguanines are presented in Figure 2. The first synthesized acyclonucleoside, containing an etheno ring, 1,N2-isopropenoacyclovir (TACV; X=A, R=CH3 Boryski et al., 1988b), has become a leading compound when it comes to searching for new antivirals of this type (Golankiewicz et al., 1991, 1994, 2001; Balzarini et al., 2002; Goslinski et al., 2002, 2003; Ostrowski et al., 2005, 2006, 2009; Horejsi et al., 2006).

Figure 2.

Selected examples of antiviral acyclonucleosides derived from 1,N2-ethenoguanine.

As suggested by Amblard et al. (2009), ethenoguanine nucleosides probably act as prodrugs, releasing the active acyclonucleosides (i.e., acyclovir or other biologically active nucleoside analogs) after the hydrolysis of the etheno ring, under physiological conditions. Indeed, the antiviral activity is well-correlated with stability of tricyclic nucleosides. The most unstable analogs, equipped with 6-phenyl, substituted with electron donating groups, are the most active ones, reaching the level of activity of the parent nucleosidic drugs. Biological activity of the etheno acyclonucleosides has been described and discussed in our recent review (Jahnz-Wechmann et al., 2015), and in the previous review articles (Golankiewicz and Ostrowski, 2006; De Clercq, 2010).

Concluding remarks

The ethenonucleosides, along with furano- and pyrrolopyrimidine nucleosides (Jahnz-Wechmann et al., 2015; and references cited herein), constitute the most important class of fused nucleosides, possessing a promising therapeutic potential. In the present review, we focused our attention on the relatively new literature data, concerning the ethenonucleosides, their synthesis, chemistry and applications. Unlike the previous papers, devoted mainly to derivatives of adenosine and cytidine (see Section Introduction), our paper presents many aspects of chemistry and activity of less known derivatives of ethenoguanosine.

The state of the art in the studies of etheno compounds, described herein, may suggest that everything in this field has already been done, and almost everything has been elucidated. However, at the end of this presentation, we would like to give some examples of problems awaiting solution. Firstly, it is still unknown whether the bioactive ethenonucleosides would be of any use in clinical treatment of viral infections. Can the lower toxicity and enhanced lipophilicity of etheno prodrugs compensate their generally lower activity? Secondly, many possible etheno prodrugs of bioactive adenosine and cytidine have not yet been obtained, and there are almost no reports on biological screening in this case. We do not know what is the real stability of ethenoadenosine and ethenocytidine derivatives under physiological conditions, which would be critical to determine their possible therapeutic applications. Moreover, the etheno modifications have not been reported for a number of modified nucleosides, like aza- and deaza-analogs, 8-substituted purine nucleosides, or derivatives of 2-aminopurine, which could form both angular and linear etheno isomers. Finally, the not yet studied ring opening reaction of the angular N2,3-ethenoguanosine may find interesting synthetic applications.

Author contributions

ZJ, literature search, organization of references, final correction. GF, literature search, graphical art, final correction. PJ, literature search, critical analysis of data. JB, general conception, writing the manuscript, coordination of the team work.

Funding

The financial support from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education under statutory financing and the KNOW program is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Amblard F., Fromentin E., Detorio M., Obikhod A., Rapp K. L., McBrayer T. R., et al. (2009). Synthesis, antiviral activity, and stability of nucleoside analogs containing tricyclic bases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 44, 3845–3851. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J., Ostrowski T., Goslinski T., De Clercq E., Golankiewicz B. (2002). Pronounced cytostatic activity and bystander effect of a novel series of fluorescent tricyclic acyclovir and ganciclovir derivatives in herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene-transduced tumor cell lines. Gene Therapy 9, 1173–1182. 10.1038/sj.gt.3301779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio J. R., Sattsangi P. D., Gruber B. A., Dammann L. G., Leonard N. J. (1976). Species responsible for the fluorescence of 3,N4-ethenocytidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98, 7408–7413. 10.1021/ja00439a049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio J. R., Secrist J. A., III, Leonard N. J. (1972). Fluorescent derivatives of adenosine and cytidine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 46, 597–604. 10.1016/S0006-291X(72)80181-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin H., Zhou X. X., Glemarec C., Chattopadhyaya J. (1987). En efficient synthesis of Y-nucleoside (wyosine) by regiospecific methylation of N4-desmethylwyosine using organozinc reagent. Tetrahedron Lett. 28, 3275–3278. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)95491-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat J., Ciesiolka J., Gornicki P., Adamiak R. W., Krzyzosiak W. J., Wiewiorowski M. (1978). New observations concerning chloroacetaldehyde reaction with some transfer-RNA constituents – stable intermediztes, kinetics and selectivity of reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 5, 789–804. 10.1093/nar/5.3.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobstein S. H., Gebert R., Grunberger D., Nakanishi K., Weinstein I. B. (1975). Structure of the fluorescent nucleoside of yeast phenylalanine transfer ribonucleic acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 167, 668–673. 10.1016/0003-9861(75)90510-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnac L. F., Mansky L. M., Patterson S. E. (2013). Structure-activity relationships and design of viral mutagens and application to lethal mutagenesis. J. Med. Chem. 56, 9403-9414. 10.1021/jm400653j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J. (1990). 1,N2-Ethenoguanosine: three methods of synthesis. Nucleosides Nucleotides 9, 803–813. 10.1080/15257779008043146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J. (1996). Transglycosylation reactions of purine nucleosides. A review. Nucleosides Nucleotides 15, 771–791. 10.1080/07328319608002422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J. (2008). Reactions of transglycosylation in the nucleoside chemistry. Curr. Org. Chem. 12, 309–325. 10.2174/138527208783743723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J., Folkman W., Golankiewicz B. (1988a). A novel route to 3-methylguanosine by chemical degradation of wyosine. Tetrahedron Lett. 29, 4163–4164. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)80445-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J., Golankiewicz B., De Clercq E. (1988b). Synthesis and antiviral activity of novel N-substituted derivatives of acyclovir. J. Med. Chem. 31, 1351–1355. 10.1021/jm00402a017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J., Golankiewicz B., De Clercq E. (1991). Synthesis and antiviral activity of 3-substitued derivatives of 3,9-dihydro-9-oxo-5H-imidazol[1,2-a]purines, tricyclic analogues of acyclovir and ganciclovir. J. Med. Chem. 34, 2380–2383. 10.1021/jm00112a010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J., Ostrowski T., Baranowski D., Goslinski T., Golankiewicz B. (1996). Oxidative cleavage of the tricyclic derivatives of 9-substituted guanines. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 61, 38–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Boryski J., Ueda T. (1985). A new simple synthesis of N-2-metylguanosine and its analogues via derivatives of 4-desmetylwyosine. Nucleosides Nucleotides 4, 595–606. 10.1080/07328318508081892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calabretta A., Leumann C. J. (2013). Base pairing and miscoding properties of 1,N6-ethenoadenine- and 3,n4-ethenocytosine-containing rna oligonucleotides. Biochemistry 52, 1990–1997. 10.1021/bi400116y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. (2010). The next ten stories on antivral drug discovery (part e): advents, advances and adventures. Med. Res. Rev. 31, 118–160. 10.1002/med.20179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elion G. B., Furman P. A., Fyfe J. A., de Miranda P., Beauchamp L., Schaeffer H. J. (1977). Selectivity of action of an anti-herpetic agent, 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 5716–5720. 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glemarec C., Wu J.-C., Remaud G., Bazin H., Oivanen M., Lönnberg H., et al. (1988). Structure and reactivity of wyosine (Y-nucleoside) and its derivatives. Chemical, kinetic and spectroscopic studies. Tetrahedron 44, 1273–1290. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)85908-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golankiewicz B., Folkman W. (1983). Methylation of desmethyl analogue of Y nucleosides. Wyosine from guanosine. Nucl. Acids Res. 11, 5243–5255. 10.1093/nar/11.15.5243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golankiewicz B., Ostrowski T. (2006). Tricyclic nucleoside analogues as antiherpes agents. Antiviral Res. 71, 134–140. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golankiewicz B., Ostrowski T., Andrei G., Snoeck R., De Clercq E. (1994). Tricyclic analogues of acyclovir and ganciclovir. Influence of substituents in the heterocyclic moiety on the antiviral activity. J. Med. Chem. 37, 3187–3190. 10.1021/jm00045a025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golankiewicz B., Ostrowski T., Boryski J., De Clercq E. (1991). Synthesis of acyclowyosine and acyclo-3-methylguanosine, as probes for some chemical and biological properties resulting from the N-3-substitution of guanosine and its analogues. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 589–593. 10.1039/p19910000589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golankiewicz B., Ostrowski T., Goslinski T., Januszczyk P., Zeidler J., Baranowski D., et al. (2001). Fluorescent tricyclic analogues of acyclovir and ganciclovir. A structure – antiviral activity study. J. Med. Chem. 44, 4284–4287. 10.1021/jm010922s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding B. T., Slaich P. K., Kennedy G., Bleasdale C., Wattson W. P. (1996). Mechanism of formation of adducts from recations of glycidaldehyde with 2′-deoxyguanosine and/or guanosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 9, 147–157. 10.1021/tx950057c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Bombarelli R., González-Pérez M., Arenas-Valgañón J., Céspedes-Camacho I. F., Calle E. (2011). DNA-damaging disinfection byproducts: alkylation mechanism of mutagenic mucohalic acids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9009–9016. 10.1021/es202251b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslinski T., Golankiewicz B., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. (2002). Synthesis and biological activity of strongly fluorescent tricyclic analogues of acyclovir and ganciclovir. J. Med. Chem. 45, 5052–5057. 10.1021/jm020827z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslinski T., Wenska G., Golankiewicz B., Balzarini J., De Clercq E. (2003). Synthesis and fluorescent properties of 6-(4-biphenylyl)-3,9-dihydro-9-oxo-5H-imidazol[1,2-a]purine analogues of acyclovir and ganciclovir. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 22, 911–914. 10.1081/NCN-120022684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P., Raney V. M. (1992). Formation of etheno adducts of adenosine and cytidine from 1-halooxiranes. evidence for a mechanism involving initial reaction with the endocyclic nitrogen atoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 1074–1080. 10.1021/ja00029a041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horejsi K., Andrei G., De Clercq E., Snoeck R., Pohl R., Holy A. (2006). Tricyclic etheno analogs of PMEG and PMEDAP: synthesis and biological activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14, 8057–8063. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itaya T., Watanabe T., Matsumoto H. (1980). A simple synthesis of 3-β-D-ribofuranosylwye and the stability of its glycosidic bond. JCS Chem. Comm. 1158–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnz-Wechmann Z., Framski G., Januszczyk P., Boryski J. (2015). Bioactive fused heterocycles: Nucleoside analogs with an additional ring. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 97, 388–396. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H., Goto M., Ikeda K., Zama M., Mizuno Y., Takemura S., et al. (1976). Structure of wye (Yt Base) and wyosine (Yt) from torulopsisi utilis phenylalanine transfer ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 15, 898–904. 10.1021/bi00649a027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kifli N., De Clercq E., Balzarini J., Simons C. (2004). Novel imidazo[1,2-c]pyrimidine base-modified nucleosides: synthesis and antiviral evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12, 4245–4252. 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochetkov N. K., Shibaev V. N., Kos A. A. (1971). New reaction of adenine and cytosine derivatives, potentially useful for nucleic acids modifications. Tetrahedron Lett. 12, 1993–1996. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96762-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kost A. A., Ivanov M. V. (1980). Etheno derivatives of adenine and cytosine (review). Chem. Heterocyclic Comp. 16, 209–221. 10.1007/BF02401711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krzyzosiak W. J., Biernat J., Ciesiolka J., Gornicki P., Wiewiorowski M. (1983). Comparative studies on reactions of adenosine and cytidine with chloroacetaldehyde, α-Bromopropionaldehyde and chloroacetone synthesis of 1,N6-Ethenoadenosine and 3,N4-ethenocytidine derivatives methylated at the etheno bridge. Polish. J. Chem. 57, 779. [Google Scholar]

- Kusmierek J. T., Folkman W., Singer B. (1989). Synthesis of N2,3-ethenodeoxyguanosine, N2,3-ethenodeoxyguanosine 5′-phosphate, and N2,3-ethenodeoxyguanosine 5′-triphosphate. Stability of the glycosyl bond in the monomer and in poly(dG,εdG-dC). Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2, 230–233. 10.1021/tx00010a003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmierek J. T., Jensen D. E., Spengler S. J., Stolarski R., Singer B. (1987). Synthesis and properties of N2,3-ethenoguanosine and N2,3-ethenoguanosine 5′diphosphate. J. Org. Chem. 52, 2374–2378. 10.1021/jo00388a007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmierek J. T., Singer B. (1992). 1, N2-ethenodeoxyguanosine: preparation, properties and formation in chloroacetaldehyde-treated polinucleotides and DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 5, 634–638. 10.1021/tx00029a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard N. J. (1984). Etheno-substituted nucleotides and coenzymes – fluorescence and biological activity. CRC Critical Rev. Biochem. 15, 125–199. 10.3109/10409238409102299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard N. J., Cruickshank K. A. (1985). Nucleoside annelating reagents: n-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-2-bromoacetamide and 2-Chloroketene diethyl acetal. J. Org. Chem. 50, 2480–2488. 10.1021/jo00214a015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mäki J., Sjöholm R., Kronberg L. (1999). Formation of oxalo-substituted etheno derivatives in reactions of mucochloric acid with adenosine, guanosine and cytidine. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 2923–2928. 10.1039/a905529k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V., Offerman R. J. (1985). Ring-extended products from the reaction of epoxy carbonyl compounds and nucleic acid bases. J. Org. Chem. 50, 5627–5631. 10.1021/jo00350a039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V., Offerman R. J., Turner G. A. (1984). Structural alteration of nucleic acid bases by bromomalonaldehyde. J. Org. Chem. 49, 4021–4025. 10.1021/jo00195a030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V., Turner G. A. (1984). Determination of the structure of the adduct from guanosine and glycidaldehyde. Tetrahedron Lett. 25, 247–250. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)99852-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M., Matsuda T., Ogata A., Hamasaki T., Kumanogoh A., Toyofuku T., et al. (2013). DNA damage in rheumatoid arthritis: an age-dependent increase in the lipid peroxidation-derived dna adduct, heptanone-etheno-2′-deoxycytidine. Autoimmune Dis. 2013:183487. 10.1155/2013/183487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski T., Golankiewicz B., De Clercq E., Andrei G., Snoeck R. (2009). Synthesis and anti-VZV activity of 6-heteroaryl derivatives of tricyclic acyclovir and 9-{[cis-1′,2′-bis(hydroxymethyl)cycloprop-1′-yl]methyl}guanine analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 44, 3313–3317. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski T., Golankiewicz B., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. (2005). Fluorosubstitution and 7-alkylation as prospective modifications of biologically active 6-aryl derivatives of tricyclic acyclovir and ganciclovir analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13, 2089–2096. 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski T., Golankiewicz B., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. (2006). Synthesis and biological activity of tricyclic analogues of 9-{[cis-1′,2′-bis(hydroxymethyl)cycloprop-1′-yl]methyl}guanine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14, 3535–3542. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski T., Zeidler J., Goslinski T., Golankiewicz B. (2000). Substituent—directed aralkylation and alkylation reactions of the tricyclic analogues of acyclovir and guanosine. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 19, 1911–1929. 10.1080/15257770008045468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattsangi P. D., Barrio J. R., Leonard N. J. (1980). 1,N6-Etheno-bridged adenines and adenosines. Alkyl substitution, fluorescence properties, and synthetic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 770–774. 10.1021/ja00522a055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sattsangi P. D., Leonard N. J., Frihart C. R. (1977). 1, N2-Ethenoguanine and N2,3-ethenoadenine. Synthesis and comparison of the electronic spectral properties of these linear and angular triheterocycles related to the Y bases. J. Org. Chem. 42, 3292–3296. 10.1021/jo00440a020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman L. H., Pelka H. (1976). Locations of accessible bases in Escherichia-coli formylmetionine transfer-RNA as determined by chemical modification. Biochemistry 15, 5769–5775. 10.1021/bi00671a013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secrist J. A., III, Bario J. R., Leonard N. J., Weber G. (1972). Fluorescent modification of adenosine-containing coenzymes – biological activities and spectroscopic properties. Biochemistry 11, 3499–3506. 10.1021/bi00769a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto H., Takesue T., Ikemura T. (1985). Reaction of malonaldehyde with nucleic acids. ii. formation of fluorescent pyrimido[1,2-a]purin-10(3h)-one mononucleotide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 58, 3431–3435. 10.1246/bcsj.58.3431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R., Hachmann J. (1966). The reaction of guanine derivatives with 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds. Biochemistry 5, 2799–2807. 10.1021/bi00873a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer B., Spengler S. J., Chavez F., Kusmierek J. T. (1987). The vinyl chloride-derived nucleosides, N2,3-ethenoguanosine, is a highly efficient mutagen in transcription. Carcinogenesis 8, 745–747. 10.1093/carcin/8.5.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner R. F., Kinner W., Lunasin A., Delac J. (1973). Fluorescent derivatives of polyribonucleotides containing epsilon-adenosine. Biochem. Biophys Acta 294, 24–37. 10.1016/0005-2787(73)90311-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virta P., Holmström T., Munter T., Nyholm T., Kronberg L., Sjöholm R. (2003). Fluorescent 7- and 8-methyl etheno derivatives of adenosine and 6-amino-9-ethylpurine: syntheses and fluorescence properties. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 22, 85–98. 10.1081/NCN-120018625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M.-S., Chu Z.-L., Niu H.-Y., Qu G.-R., Guo H.-M. (2014). A copper-catalyzed domino route toward purine-fused tricyclic derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 79, 1093–1099. 10.1021/jo4025489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N., Kato M. (1975). Synthesis of 2-aza-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphate via 1,N6-etheno-adenosine 3′, 5′-cyclic phosphate. Chem. Lett. 311–314. 10.1246/cl.1975.311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N., Suda K., Onoue Y., Kato M. (1977). Studies on the syntheses of compounds related to adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphate. removal of etheno group of 2-substituted 1,N6-etheno-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphates. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 25, 3239–3246. 10.1248/cpb.25.3239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N., Yuasa Y., Kato M. (1976). The synthesis of 2-substituted 1,N6-etheno-adenosine-3′, 5′-cyclic phosphate by ring reclosure of alkali-hydrolizate of 1,N6-etheno-adenosine-3′, 5′-cyclic phosphate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 24, 1561–1567. 10.1248/cpb.24.1561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yip K. F., Tsou K. C. (1973). Synthesis of fluorescent adenosine derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 14, 3087–3090. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96326-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler J., Golankiewicz B. (1998). A case of unusual sterically driven c-tritylation reaction of tricyclic analogues of acyclovir. Tetrahedron 54, 2941–2952. 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)83029-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]