Abstract

Introduction

Both end-organ damage and high red cell distribution width (RDW) values are associated with adverse cardiovascular events, inflammatory status, and neurohumoral activation in hypertensive disease and in the general population. In this study, we investigated the relationship between RDW and end-organ damage in hypertensive patients.

Material and methods

The 446 systo-diastolic hypertensive patients included in the study received 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Left ventricular mass index, glomerular filtration rate, and microalbuminuria were measured to identify end-organ damage. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels of all patients were also examined.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 49.96 ±11.04 years. The mean RDW was 13.06 ±1.05%. Red cell distribution width was positively correlated with left ventricular myocardial index (LVMI), urinary albumin, hs-CRP, and NT-proBNP (r = 0.298, p < 0.001; r = 0.228, p < 0.001; r = 0.337, p < 0.001; r = 0.277, p < 0.001, respectively), while RDW was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = –0.153, p < 0.001). Additionally, while there was a positive correlation between RDW and 24-h systolic blood pressure, no correlation was found between RDW and 24-h diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.132, p = 0.006 and r = 0.017, p = 0.725, respectively). Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that RDW levels were independently associated with eGFR, LVMI, and severity of albuminuria (β = 0.126, p = 0.010; β = –0.149, p = 0.002; β = 0.114, p = 0.035).

Conclusions

High RDW levels in systo-diastolic hypertensive patients were found to be an independent predictor of end-organ damage.

Keywords: red cell distribution width, hypertension, end-organ damage

Introduction

Hypertension is a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular event development. In particular, hypertensive patients with end-organ damage are associated with increased cardiovascular events [1, 2], while end-organ damage development in hypertensive patients is reported to be associated with increased inflammation and neurohumoral activation [3–5]. Increases in inflammation and neurohumoral activation cause increased red cell distribution width (RDW), and increased RDW levels that reflect size heterogeneity of the erythrocytes in the circulation are also reported to be associated with heart failure, coronary artery disease, and increased mortality in the general population [6–9].

Left ventricular myocardial index (LVMI), microalbuminuria, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) are the most frequently used indicators of end-organ damage in hypertensive patients. While there are studies on the association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels with end-organ damage in hypertensive patients, not many studies have investigated the association between RDW and development of end-organ damage [3–5]. In this study, therefore, the association between RDW and end-organ damage, hs-CRP, and NT-proBNP was investigated in systo-diastolic hypertensive patients.

Material and methods

A total of 446 patients aged between 20–87 years, who had presented at the cardiology outpatient clinic and had office blood pressure over 140/90 at least twice at different times, were included in the study. All patients were put on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Medical history, physical examination findings and anthropometric measurements of the patients were recorded by an experienced cardiologist.

Hypertension was defined as an office blood pressure (OBP) of ≥ 140/90 mm Hg or the active use of antihypertensive drugs [10]. Sustained systo-diastolic hypertension was defined as having an OBP of ≥ 140/90 mm Hg and the daytime ABPM mean of ≥ 135/85 mm Hg, or the nighttime ABPM mean of ≥ 120/70 mm Hg [10]. “White-coat-hypertension” was defined as blood pressure if elevated in the office at repeated visits and normal on ABPM [10].

Diabetes was defined based on the American Diabetes Association criteria (fasting serum glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl (7 mmol/l), or non-fasting glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l), or active use of anti-diabetic treatment) [11]. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms/(height in meters)2, and eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula [12].

Urinary albumin was expressed in milligrams per gram (mg/g). Albuminuria was defined as an albumin/creatinine (A/C) ratio of 30 mg/g or higher, stratified into two groups of microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria with an A/C ratio of 30–299 mg/g and 300 mg/g or higher, respectively.

Echocardiographic examinations were performed by a cardiologist using the Vivid 7 system (General Electric Vivid 7 GE Vingmend Ultrasound AS, Horten, Norway). The left ventricular (LV) mass in grams was calculated from M-mode echocardiograms according to the formula described by Devereux et al. [13]. Left ventricular mass was indexed to body surface area as LV mass index (LVMI) in g/m2 of body surface area.

The exclusion criteria of this study were secondary hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, moderate-to-severe valvular disease, chronic renal failure, chronic liver disease, thromboembolic disorders, hematological abnormalities, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The local ethics committee approved the study protocol and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) was performed for 24 h using an ambulatory blood pressure monitor (Tonoport V, GE Healthcare). The monitor was programmed to measure the blood pressure every 20 min. Daytime and nighttime blood pressure was defined as measured from 07:00 AM to 11:00 PM and from 11:00 PM to 07:00 AM, respectively. Twenty-four hour mean systolic blood pressure was defined as the mean systolic blood pressure measured during 24 h by the monitor and was automatically provided in the report.

Blood sampling

Red cell distribution width was measured in blood samples collected in EDTA tubes, which were analyzed with an automated hematology analysis system (Mindray BC5800). Normal RDW values ranged from 11% to 16% in our laboratory. Standard laboratory parameters, including total leukocyte and neutrophil counts, hematocrit, glucose and creatinine levels and lipid profiles, were determined with standard methods. Plasma NT-proBNP levels were measured using a Cobas e411 device (Roche, Germany) via the immunoassay method. The NT-proBNP reference values were determined as 0–125 pg/ml. Hs-CRP was measured using a BN2 model nephelometer.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 20. The variables were investigated using visual (histograms, probability plots) and analytical methods (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) to determine whether they were normally distributed. Descriptive analyses were presented using means and standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed variables, medians and maximum-minimum values for non-normally distributed variables, and percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square (χ2), Student's t, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used where appropriate. A Spearman correlation analysis was performed to determine the association of RDW with the examined variables. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to identify the significance of the relationship of RDW levels with microalbuminuria, LVMI, and eGFR. An overall 5% type-I error level was used to infer statistical significance.

Results

Of the 446 participants included in the study, 72.7% had sustained systo-diastolic hypertension and 27.3% had white-coat hypertension. Male patients constituted 51.1% of the sample. The mean age was 49 ±11.04 years; 23.3% of the participants were smokers and 14.4% had type 2 diabetes mellitus. The mean value of RDW was 13.06 ±1.05%, LVMI was 96.04 ±25.6 g/m2, urinary albumin was 63.72 ±127.09 mg/g, eGFR was 97.14 ±17.99 ml/min/1.73 m2, hs-CRP was 3.96 ±4.62 mg/l and NT-proBNP was 55.21 ±69.99 pg/ml. The other demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Characteristics of the study population

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Gender (male), n (%) | 228 (51.1) |

| Age [years] | 49.96 ±11.04 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 29.46 ±4.46 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 104 (23.3) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 64 (14.4) |

| 24-h SBP [mg/dl] | 145 ±64 |

| 24-h DBP [mg/dl] | 88.35 ±13 |

| Glucose [mg/dl] | 104.5 ±28.6 |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 0.8 ±0.2 |

| Total cholesterol [mg/dl] | 204.4 ±43.57 |

| LDL cholesterol [mg/dl] | 132.14 ±39.27 |

| HDL cholesterol [mg/dl] | 46.64 ±13.37 |

| Triglyceride [mg/dl] | 163.71 ±91.94 |

| Uric acid [mg/dl] | 5.37 ±1.57 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.9 ±4.4 |

| Platelet count [× 103/µl] | 265.97 ±73 |

| RDW (%) | 13.06 ±1.05 |

| LVMI [g/m2] | 96.04 ±25.6 |

| eGFR [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 97.14 ±17.99 |

| Urinary albumin [mg/g] | 63.72 ±127.09 |

| Hs-CRP [mg/l] | 3.96 ±4.62 |

| NT-proBNP [pg/ml] | 55.21 ±69.99 |

HDL – high-density lipoprotein, LVMI – left ventricular mass index, NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, SBP – systolic blood pressure, RDW – red cell distribution width, hsCRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate.

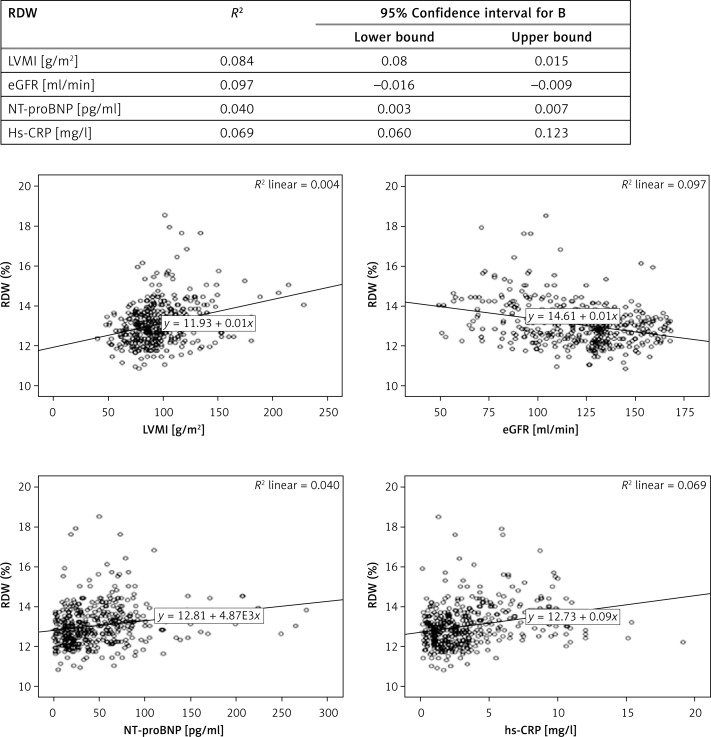

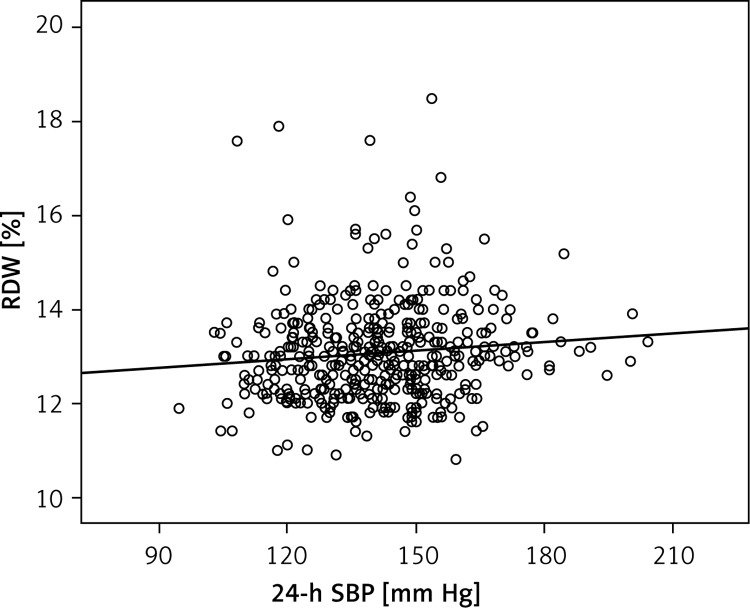

As shown in Figure 1 and Table II, RDW was positively correlated with LVMI, albuminuria, hs-CRP, and NT-proBNP (r = 0.298, p < 0.001; r = 0.228, p < 0.001; r = 0.337, p < 0.001; r = 0.277, p < 0.001, respectively), while RDW was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = –0.153, p < 0.001). Additionally, while there was a positive correlation between RDW and 24-h systolic blood pressure, no correlation was found between RDW and 24-h diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.132, p = 0.006 and r = 0.017, p = 0.725, respectively) (Figure 2, Table II).

Figure 1.

Correlation between red cell distribution width (RDW) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), microalbuminuria, left ventricular mass index (LVMI), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

Table II.

Correlation coefficients of the relationship between red cell distribution width (RDW) and selected variables

| Variable | β | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| NT-proBNP | 0.277 | < 0.001 |

| Urinary albumin [mg/g] | 0.0228 | < 0.001 |

| LVMI | 0.298 | < 0.001 |

| hs-CRP | 0.337 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR | –0.153 | < 0.001 |

| 24-h SBP | 0.132 | 0.006 |

| 24-h DBP | 0.017 | 0.725 |

NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, LVMI – left ventricular mass index, hs-CRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, SBP – systolic blood pressure, DBP – diastolic blood pressure, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 2.

Correlation between red cell distribution width (RDW) and 24-h systolic blood pressure

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that RDW levels were independently associated with eGFR, LVMI, and severity of albuminuria (β = 0.126, p = 0.010; β = –0.149, p = 0.002; β = 0.114, p = 0.035) (Table III).

Table III.

Multiple linear regression analyses: relationship between left ventricular mass index (LVMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), urinary albumin and selected variables

| Variable | Coefficient | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable – eGFR: (r 2 = 0.219) | ||

| RDW | –0.126 | 0.010 |

| Hs-CRP | –0.079 | 0.113 |

| NT-proBNP | –0.144 | 0.040 |

| 24-h SBP | –0.013 | 0.741 |

| 24-h DBP | –0.073 | 0.142 |

| Uric acid | –0.388 | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 0.055 | 0.254 |

| Dependent variable – urinary albumin: (r 2 = 0.048) | ||

| RDW | 0.114 | 0.035 |

| Hs-CRP | 0.109 | 0.047 |

| NT-proBNP | 0.010 | 0.851 |

| 24-h SBP | 0.021 | 0.662 |

| 24-h DBP | 0.106 | 0.053 |

| Uric acid | 0.029 | 0.583 |

| BMI | 0.010 | 0.852 |

| Dependent variable – LVMI: (r 2 = 0.238) | ||

| RDW | 0.149 | 0.002 |

| Hs-CRP | 0.335 | < 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP | 0.156 | 0.001 |

| 24-h SBP | 0.080 | 0.091 |

| 24-h DBP | 0.090 | 0.065 |

| Uric acid | 0.054 | 0.256 |

| BMI | –0.045 | 0.348 |

NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, LVMI – left ventricular mass index, hs-CRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, SBP – systolic blood pressure, DBP – diastolic blood pressure, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate, BMI – body mass index, RDW – red cell distribution width.

Discussion

Based on the results of this study, increased RDW levels were identified as independent predictors of increased LVMI, decreased eGFR values and severity of microalbuminuria in systo-diastolic hypertensive patients. Also, it was determined that RDW levels were correlated with hs-CRP, NT-proBNP levels and 24-h systolic blood pressure.

End-organ damage development in hypertensive patients is a significant indicator of cardiovascular risk. Diagnosis of kidney damage associated with hypertension is made by the detection of symptoms of declining kidney function or increased urinary albuminuria [14]. We demonstrated that increased RDW levels were independent predictors of decreased eGFR values, although the creatinine values were within the normal range. Our results are in agreement with those of Lippi et al., who also reported that a low eGFR was a predictor of high RDW values [15]. In another study, a strong association between decreased renal function and high RDW levels was attributed to impaired erythrocyte maturation in chronic kidney disease patients due to increased inflammation [16].

Another finding that demonstrates impaired renal function in hypertensive patients is the degree of microalbuminuria. Microalbuminuria is associated with increased cardiovascular risk in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients who are undergoing treatment [1, 17]. Microalbuminuria is not only a predictor of subclinical renal damage but is also a predictor of generalized endothelial dysfunction and increased inflammation [3, 18]. A study conducted on grade 1 hypertensive patients reported an association between increased RDW and endothelial dysfunction [19], and a population-based study by Afonso et al. found an association between an increase in RDW and proteinuria development; this was attributed to inflammation, neurohumoral activation, and endothelial dysfunction [20]. In our study, we also found that increased RDW levels were independent predictors of microalbuminuria.

Left ventricular hypertrophy, like microalbuminuria, has also been demonstrated to be a predictor of poor cardiovascular prognosis [2, 21]. In our study we demonstrated that high RDW levels were an independent predictor of LVMI. Since increased neurohumoral activation and inflammation are associated with increased LVMI in hypertensive patients [5, 22], these factors may be responsible for the association between LVMI and RDW. Kilicaslan et al. recently demonstrated that RDW values were associated with ventricular geometrical patterns [23] in untreated hypertensive patients.

Studies have indicated that systolic blood pressure (SBP) has a greater association with RDW levels and mortality than does diastolic blood pressure (DBP) [7, 9, 24]. While we detected a positive correlation between 24-hour SBP and RDW, we could not detect an association between DBP and RDW. Systolic hypertension has also been shown to be more closely associated with increased inflammation and NT-proBNP than is diastolic hypertension [25, 26]. This may explain the different associations of RDW with SBP and DBP.

At least a part of the association of RDW with increased cardiovascular incidence and mortality was attributed to the association between RDW and inflammation [8, 9]. However, Perlstein et al. found that increased RDW levels were associated with increased mortality among a patient population with low CRP [8]. In patients with coronary artery disease, Fukuta et al. reported high RDW values associated with increased BNP values, but no association was detected with hs-CRP levels [27]. Fukuta et al. proposed that the association between RDW and adverse clinical incidents in the studied patient population was related to neurohumoral activation rather than inflammation. The renin-angiotensin system, inflammation, and oxidative stress are hyperactive in hypertension [28, 29], and increases in these factors have been associated with increased end-organ damage and increased RDW levels [5, 30, 31].

To our best knowledge there is no study assessing the association of RDW level with NT-proBNP, hs-CRP levels and end-organ damage in hypertensive patients. In our study, we determined that a high RDW level was a predictor of end-organ damage in hypertensive patients. Moreover, we found that RDW was associated with hs-CRP and NT-proBNP levels. Increased neurohumoral activation and inflammation may, therefore, be the cause of the association between increased RDW and adverse cardiovascular events observed in hypertensive patients.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this was a non-randomized study and therefore was subject to selection bias. Second, hypertensive patients with heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, and moderate-to-severe vascular disease were excluded. Thus, our findings cannot be generalized to the entire hypertensive population. Also, normotensive patients were not included in this study. Finally, we did not measure vitamin B12, folate levels, and iron status, which may also affect RDW levels.

In conclusion, increased RDW levels are associated with end-organ damage, increased inflammation and NT-proBNP levels in systolo-diastolic hypertensive patients. This association may be used for risk classification in this patient group.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.DeLeeuw PW, Ruilope LM, Palmer CR, et al. Clinical significance of renal function in hypertensive patients at high risk: results from the INSIGHT trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2459–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy D, Salomon M, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Prognostic implications of baseline electrocardiographic features and their serial changes in subjects with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1994;90:1786–93. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsioufis C, Dimitriadis K, Andrikou E, et al. ADMA, C-reactive protein, and albuminuria in untreated essential hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1050–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen MH, Hansen TW, Christensen MK, et al. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide is inversely related to metabolic cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2005;46:660–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000179575.13739.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebrandt P, Boesen M, Olsen M, et al. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide in arterial hypertension – a marker for left ventricular dimensions and prognosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:313–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felker GM, Allen LA, Pocock SJ, et al. CHARM Investigators Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Arnold M, Moye L, Davis B, Pfeffer M, the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Trial Investigators Relation between red blood cell distribution width and cardio-vascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2008;117:163–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlstein TS, Weuve J, Pfeffer MA, Beckman JA. Red blood cell distribution width and mortality risk in a community-based prospective cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:588–94. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel KV, Ferrucci L, Ershler WB, Longo DL, Guralnik JM. Red blood cell distribution width and the risk of death in middle-aged and older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:515–23. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology Guidelines committee. 2013 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–19. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsushita K, Mahmodi BK, Woodward M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA. 2012;307:1941–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux R, Koren M, de Simone G, Okin PM, Kligfield P. Methods for detection of left ventricular hypertrophy: application to hypertensive heart disease. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:8–15. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.suppl_d.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippi G, Targher G, Montagnana M, Salvagno GL, Zoppini G, Guidi GC. Relationship between red blood cell distribution width and kidney function tests in a large cohort of unselected outpatients. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2008;68:745–8. doi: 10.1080/00365510802213550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss G, Goodnough L. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen JS, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S, Schroll M, Borch-Johnsen K. Arterial hypertension microalbuminuria risk of ischemic heart disease. Hypertension. 2000;35:898–903. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.4.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stehouver CDA, Smulders YM. Microalbuminuria and risk for cardiovascular disease: analysis of potential mechanisms. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2106–11. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zairowa AR, Oshchepkowa EV, Rogoza AN. Vasomotor endothelial dysfunction in young men with grade 1 arterial hypertension. Kardiologiia. 2013;53:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afonso L, Zalawadiya SK, Veeranna V, Panaich SS, Niraj A, Jacob S. Relationship between red cell distribution width and microalbuminuria: a population-based study of multiethnic representative US adults. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119:c277–82. doi: 10.1159/000328918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reichek N, Devereux RB. Left ventricular hypertrophy: relationship of anatomic, echocardiographic and electrocardiographic findings. Circulation. 1981;63:1391–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.6.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kılıcaslan B, Dursun H, Aydın M, Ekmekci C, Ozdoğan O. The relationship between red cell distribution width and abnormal left ventricle geometric patterns in patients with untreated essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:560–4. doi: 10.1038/hr.2014.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiguete E, Ochoa-Guzman A, Vargas-Sanchez A, et al. Blood pressure at hospital admission and outcome after primary intra cerebral hemorrhage. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:34–9. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.33346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pusuroglu H, Erturk M, Akgul A, et al. Plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels identifying non-dipping pattern in patients with hypertension. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2014;20:64–85. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusuroglu H, Erturk M, Akgul A, et al. A comparative analysis of leukocyte and leukocyte subtype counts among isolated systolic hypertensive, systo-diastolic hypertensive and nonhypertensive patients. Kardiol Pol. 2014 Mar 27; doi: 10.5603/KP.a2014.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuta H, Ohte N, Mukai S, et al. Elevated plasma levels of B-type natriuretic peptide but not C-reactive protein are associated with higher red cell distribution width in patients with coronary artery disease. Int Heart J. 2009;50:301–12. doi: 10.1536/ihj.50.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chae CU, Lee RT, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Blood pressure and inflammation in apparently healthy men. Hypertension. 2001;38:399–403. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildiz A, Gur M, Yilmaz R, et al. Lymphocyte DNA damage and total antioxidant status in patients with white-coat hypertension and sustained hypertension. Arch Turk Soc Cardiol. 2008;36:231–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierce CN, Larson DF. Inflammatory cytokine inhibition of erythropoiesis in patients implanted with a mechanical circulatory assist device. Perfusion. 2005;20:83–90. doi: 10.1191/0267659105pf793oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato H, Ishida J, Imagawa S, et al. Enhanced erythropoiesis mediated by activation of renin-angiotensin system via angiotensin II type 1areceptor. FASEB J. 2005;19:2023–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3820fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]