Abstract

Summary: We present rCGH, a comprehensive array-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis workflow, integrating computational improvements and functionalities specifically designed for precision medicine. rCGH supports the major microarray platforms, ensures a full traceability and facilitates profiles interpretation and decision-making through sharable interactive visualizations.

Availability and implementation: The rCGH R package is available on bioconductor (under Artistic-2.0). The aCGH-viewer is available at https://fredcommo.shinyapps.io/aCGH_viewer, and the application implementation is freely available for installation at https://github.com/fredcommo/aCGH_viewer.

Contact: frederic.commo@gustaveroussy.fr

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Precision medicine aims at identifying individual cancer patients’ molecular alterations—such as copy number alterations (CNAs), gene mutations or fusions and protein expressions—and matching these to targeted therapies (André et al., 2014; Tsimberidou et al., 2014). While next-generation sequencing is now widely used for identifying mutations, array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) is a common platform for detecting CNAs (André et al., 2013; Laurent-Puig et al., 2009): the advantages of aCGH over next-generation sequencing technologies include lower cost, rapid turn-around time and lower computational overhead. In the context of precision medicine, CNA analysis—alongside somatic mutation analysis—is critical for identifying clinically actionable genomic aberrations. However, significant technical challenges remain in the processing of aCGH data. Addressing these challenges requires new state-of-the-art tools for coordinating analysis and interpreting results.

2 Methods and implementation

An aCGH analysis can be decomposed into four distinct phases (Supplementary Fig. S1): (i) log2 relative ratios (LRR) calculation (the sample DNA signals against a normal 2-copy DNA reference), (ii) profile centralization, (iii) profile segmentation and (iv) genomic profile interpretation to identify actionable genes affected by a CNA, to propose a matched therapeutic orientation.

The profile centralization defines a baseline—a neutral 2-copies level—from which CNA are estimated. We previously discussed the impact of centralization on aCGH analysis (Commo et al., 2015), and rCGH implements the procedure described in the same article. Briefly, the vector of LRRs is considered as a mixture of Gaussian populations, and their respective proportion and parameters are estimated using an Expectation-Maximization algorithm. By default, the sub-population with a density peak higher than 50% of the highest density is considered as representing a neutral 2-copy state. Its mean is then used for centralizing the profile.

The segmentation step aims at identifying breakpoints in the LRRs continuity, each delimiting potentially gained or lost DNA segments. The rCGH segmentation relies on the circular binary segmentation (CBS) (Olshen et al., 2004), implemented in the DNAcopy R package. Although this algorithm is widely used (Willenbrock and Fridlyand, 2005), it suffers from several parameters to be specified a priori. In particular, the ‘sdundo’ segmentation method mainly relies on two parameters: (i) a significance level α for the statistical test to accept points as breakpoints and (ii) the allowed difference between two consecutive segment means to keep them distinct (expressed in DNAcopy as a number of standard deviations,undo.SD). Instead of using arbitrary values, rCGH introduces a data-driven parameterization: given a fixed α, the corresponding optimal ‘undo.SD’ value is estimated from the median absolute deviation, a widely used noise estimator (Supplementary Methods). This optimization greatly facilitates the use of this algorithm for routine practice and standardizes the parameterization through a data-driven rule.

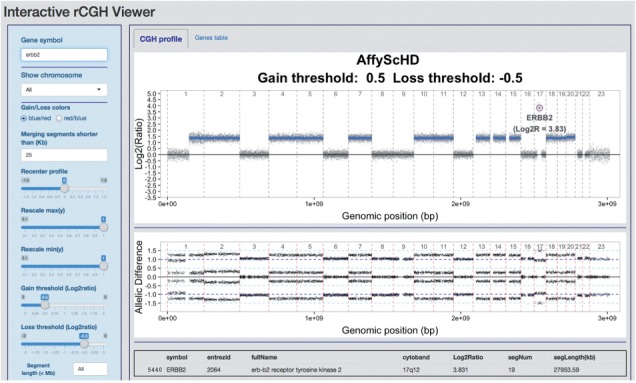

In precision medicine, the decision-making regarding a therapeutic orientation relies on the actionable gene’s status, defined with respect to gain/loss thresholds and alteration lengths. Defining such thresholds is often arbitrary: (i) there is no consensus on which LRR values correspond to biologically relevant CNAs, (ii) focal alterations, possibly referring to significantly recurrent alterations within a cohort (Mermel et al., 2011; Yuan et al., 2012), are not clearly defined when transposed to the interpretation of unique profiles. rCGH provides an interactive visualization tool that allows the user to visualize and manipulate genomic profiles from within a web interface (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

. Interactive visualization. The genomic profile and the loss of heterozygosity profile (when available) are displayed on the CGH profile tab, while the gene values are accessible through the Genes table tab. The command panel (on left) can be used to display a gene of interest, to recenter the entire profile and to specify several decision parameters (gain/loss threshold, segment length). Gene values are updated automatically, and profiles and table can be re-exported after modification

Two primary perspectives are provided: visualization of CNAs along DNA strands or a gene-centric table. The latter includes gene-specific LRR values and corresponding segment lengths. When available on microarrays, loss of heterozygosity expressed as the A/B allelic difference is also provided. A command window provides control over display parameters including re-centering, merging short segments and gain or loss thresholds (see Supplementary Methods for a full description). Finally, both the genomic profile and the genes table can be re-exported, in ready-to-publish quality and xls format, respectively, including the changes applied on the profile.

3 Supported files

As input rCGH supports Agilent Human CGH data, from 44K to 400K, and Affymetrix, SNP6 and cytoScanHD. All are provided in text format by platform-specific softwares: standard Agilent text files are exported from Agilent Feature Extraction software (FE), while Affymetrix cychp.txt, cnchp.txt or probeset.txt files are obtained by processing Affymetrix CEL files through ChAS or Affymetrix Power Tools (APT) softwares: both are freely available at http://www.affymetrix.com. Custom arrays can also be supported, provided the data format complies with the requirements (see Supplementary Methods for details).

4 rCGH outputs

rCGH stores all the original and computed data, as well as the workflow parameters, to ensure traceability. Segmentation tables are of the same format as standard CBS outputs, completed with the segment lengths and the within-segment LRR standard deviation.

5 Web server version

Independently of rCGH, we have developed aCGH-viewer: an interactive visualization available as a web application. Its implementation is freely available for installation on a server. As inputs, the application requires segmentation tables built through either rCGH, or any other workflow, provided the data are of the same form as the standard CBS outputs. This application is designed for use by clinicians and biologists and does not require bioinformatic expertise. It allows individual profiles to be shared, discussed and annotated in tumor board committees and finally saved for traceability (see Supplementary Methods for details).

6 Conclusion

In this work, we present the R package rCGH: a comprehensive aCGH analysis workflow, with features and functionalities particularly well adapted to precision medicine. rCGH ensures the traceability of the entire process of individual samples and provides interactive visualization tools allowing to better interpret—and potentially reprocess—genomic profiles, individually. The web-server application can assist oncologists in reviewing copy-number alterations in genomic profiles and identifying matched therapeutic orientations.

Funding

This work was supported by the Integrative Cancer Biology Program of the National Cancer Institute (U54CA149237 to F.C., C.F. and J.G.), Unicancer, the ARC foundation, the Breast Cancer Research foundation and Odyssea.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- André F. et al. (2014) Comparative genomic hybridisation array and DNA sequencing to direct treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a multicentre, prospective trial (SAFIR01/UNICANCER). Lancet Oncol., 15, 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André F. et al. (2013) Targeting FGFR with dovitinib (TKI258): preclinical and clinical data in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res., 19, 3693–3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commo F. et al. (2015) Impact of centralization on aCGH-based genomic profiles for precision medicine in oncology. Ann. Oncol., 26, 582–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent-Puig P. et al. (2009) Analysis of PTEN, BRAF, and EGFR status in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in wild-type KRAS metastatic colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol., 27, 5924–5930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermel C.H. et al. (2011) GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol., 12, R41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshen A.B. et al. (2004) Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics, 5, 557–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsimberidou A.M. et al. (2014) Personalized medicine for patients with advanced cancer in the phase I program at MD Anderson: validation and landmark analyses. Clin. Cancer Res., 20, 4827–4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbrock H., Fridlyand J. (2005) A comparison study: applying segmentation to array CGH data for downstream analyses. Bioinformatics, 21, 4084–4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X. et al. (2012) Comparative analysis of methods for identifying recurrent copy number alterations in cancer. PLoS One, 7, e52516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.