Abstract

Objective

To synthesize the current literature on the magnitude and impact of multiple chronic conditions on clinical outcomes, including total in-hospital and post discharge mortality and hospitalizations, in older adults with cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was conducted. Four electronic databases including Medline, PubMed, Medline Plus, Embase, as well as article bibliographies were searched for publications from 2005 to 2015 addressing the impact of multimorbidity on clinical outcomes in older adults with CVD. Identified studies were screened using pre-defined criteria for eligibility.

Results

Fifteen studies met our inclusion criteria. Most studies reported a significant association between number of chronic conditions or selected morbidities and the risk of dying. The most frequently examined conditions were diabetes, chronic kidney disease, anemia, chronic pulmonary disease, and dementia/cognitive impairment. Multimorbidity was assessed either by simply counting the numbers of conditions or by use of the Charlson and/or Elixhauser indices.

Conclusions

Multimorbidity is highly associated with the risk of dying in patients with CVD, but there are only very limited data on universal health outcomes (i.e., health related quality of life, symptom burden, and function) in this high risk population. There is also a lack of consistency in the manner in which the burden of multimorbidity has been assessed and characterized. Very few studies have addressed the true complexity of older patients with CVD. How best to characterize multimorbidity in these patients and to relate multimorbidity to clinical outcomes remains a substantial challenge.

Keywords: multimorbidity, elderly, clinical outcomes, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Approximately two thirds of American men and women 65 years of age and older have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 CVD in older men and women adversely impacts quality of life and it is the leading cause of death in older Americans. As the U.S. population has aged, the prevalence of CVD has increased dramatically, together with other chronic conditions. 2–4 There is increasing awareness that older individuals with CVD and multiple chronic conditions experience higher levels of healthcare use and poorer outcomes.4–10 Moreover, the clinical management of persons with CVD with multiple chronic conditions can be especially challenging due to complex therapeutic regimens, the involvement of multiple healthcare providers, and competing priorities impacting decision-making in the care of these patients.11

Despite the high prevalence of CVD and multimorbidity in the elderly, there remains a lack of consensus regarding how best to assess and measure multimorbidity and to determine how the presence of multiple chronic conditions impacts clinical outcomes.11 The aim of this paper is to review the current literature on the magnitude and impact of multimorbidity on clinical outcomes in older adults with CVD.

Methods

Search Strategy and Information Sources

The available published literature was reviewed by searching the electronic databases Medline, PubMed, Medline Plus, and Embase, for the time period January, 2005 through August, 2015. We used the following search terms: cardiovascular disease , myocardial infarction, heart failure,; comorbidities, multimorbidity, multiple chronic conditions; clinical outcomes, mortality, hospital readmission, rehospitalization. Search limits were used in each database to restrict our search to clinical studies, articles in the English language, and studies in the last 10 years (excluding animal studies). (See Appendix 1).

In addition to the electronic search of these databases, we hand searched the references of original articles. All references identified by the above searches were merged into a single bibliographic database.

After compiling the search results of the databases, the yield obtained by hand searching, and removing duplicate articles, the studies were reviewed by the coauthors. One of the reviewers independently examined the titles and abstracts to determine eligibility for inclusion. If the title and abstract appeared to be potentially relevant by one of the raters, the article was marked for a full text review. Any article that was marked as unsure by the rater was also marked for full text review.

The studies reviewed in our report included patients 18 years or older with confirmed CVD cared for in the hospital and clinic setting. We excluded case reports, letters to the editors, or situations where only an abstract was provided. (See PRISMA checklist for details.)

Results

Search Results

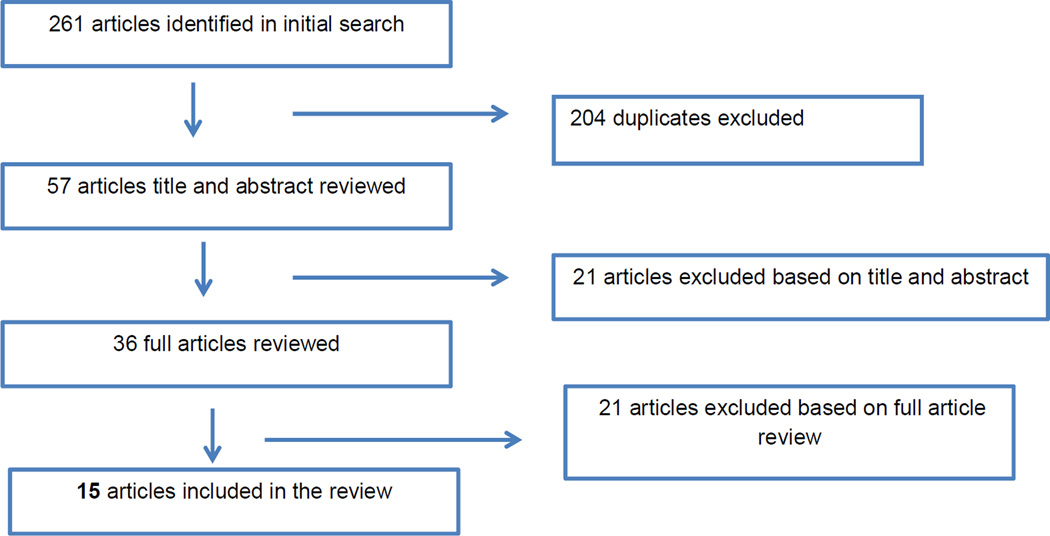

A total of 261 articles was identified from our initial literature search; after 204 duplicates were removed, and 57 articles were excluded on the basis of title and abstract review, 36 articles were retrieved for more detailed assessment. Of these, 15 studies met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). No additional articles were identified from the references of the included articles.

Figure 1.

search strategy

Study characteristics

The characteristics of included articles are detailed in Table 1. Five studies included patients with acute myocardial infarction, and 10 included patients with heart failure as the cardiovascular condition of interest. Six of the included studies were retrospective cohort studies,3,9,10,12,14 four were cross-sectional,5,15,16,17 three were prospective cohort studies,18,19,20 and two were randomized controlled trials.21,22 Seven were US-based studies;3,5,9,10,14,16,20 non-US-based studies (n= 8) were performed in Canada 13,22 and several European countries , including Italy,17 Spain,15 Portugal,12 Denmark, 21 France,18 and the Netherlands. 19 Eleven studies utilized medical records for data collection, 3,5,9,10,12,13,15,18,19,20,21 three employed claims-based data,14,16,17 and one group of authors analyzed data on multimorbidity collected in the context enrolling subjects in a large randomized controlled trial (SOLVD).22

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics

| Authors, country | Setting | Condition | Population characteristics | Study design, time period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lichtman et al5; USA 2007 |

19 medical centers (academic, inner city, and non-university hospitals) | AMI | N: 3,907. Mean age: 64 years, 40% women, 60% white. | Cross-sectional data collected from January 2003 to June 2004 |

| Gili et al;15 Spain 2011 | 2 major hospitals (ICU; department of cardiology and internal medicine) | AMI | N: 5,275. Mean age: 72 years. | Cross-sectional data collected from 2003 to 2009 |

| Picarra et al12; Portugal 2011 | 1 hospital(cardiology department) | AMI | N:132 Mean age: 83 years, 55% men | Retrospective data collected from January 2005 to December 2007 |

| McManus et al;9 USA 2012 | 11 medical centers in central MA | AMI | N: 9,581. Mean age: 70 years, 57% men, 93% Caucasian. | Retrospective data collected from1990 to 2007 |

| Chen et al;10 USA, 2013 | 11 medical centers in central MA | AMI | N: 2,972. Mean age: 71 years, 55% men, 93% Caucasian. | Retrospective data collected from 2003 to 2007 |

| Clarke et al;13 Canada 2011 | 1 tertiary care HF ambulatory clinic in | HF | N: 824. Mean age 64 years, 69% male. Mean EF: 33%. | Retrospective data collected from December 1998 to December 2004 |

| Marechaux et al;18 France 2011 | 1 hospital 70 different hospitals in | HF | N: 98. Mean age: 76 years old. 80% women. 64% had low EF. | Prospective data collected from October 2005 to September 2007 |

| Mogensen et al,21 Denmark 2011 | Denmark, Norway and Sweden | N: 8,507. Mean age 72 years old; 40% women. | Two RCTs data collected for one study (Denmark) from 1993 to 1996 and the other (Multisite in Europe) from 2001 to 2002. | |

| Ather et al;3 USA 2012 | Ambulatory clinics of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs | HF | N: 2,843 preserved and 6,599 with reduced HF. Mean age 70 years old. 95% men. 77% white. | Retrospective data collected from October 2000 to September 2002. |

| Oudejans et al;18 The Netherlands 2012 | 2 regional hospitals (geriatric outpatient clinics) | HF | N: 93. Mean age: 83 years 40% men. | Prospective data collected from July 2003 to July 2010. |

| Smith et al;14 USA 2013 | 4 health plans in CA, CO, OR, MA and WA | HF | N: 24,331; 14,579 with preserved and 9,752 with reduced HF. Mean age 74 years. 48% women. | Retrospective data collected from January 2005 to December 2008. |

| Bohm et al;22 Canada 2014 | 23 medical centers in the US, Canada and Belgium | HF | SOLVD prevent N: 4,228 Mean age: 59 years 89% male 87% white; SOLVD treatment N: 2,569 Mean age:61 80% men 80% white. | RCTs data collected from June 1986-March 1989 |

| Lee et al;16 USA 2014 | Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality Inpatient Sample (4,390 hospitals; 44 states) | HF | N: 192,327 hospitalizations for HF. Mean age: 73; female 51% 68% white. | Cross-sectional data collected during 2009 |

| Buck et al;17 Italy 2015 | Cardiovascular centers (28 provinces in northern Italy) | HF | N:628 Mean age 73 years, male 58%, | Cross-sectional data collected from 2011 to 2012 |

| Murad et al;20 USA 2015 | 4 centers, NC, CA, MA and PA | HF | N: 558 Mean age: 79, 52% men, 87% white. | Prospective data collected from 1989–1990 to 2nd wave 1992–1993 to 2002 |

Study sample sizes ranged from 9319 to more than 182,00016 participants; eight of the 15 studies 3,5,9,10,14,16,21,22 included <1,000 subjects. All 15 studies provided information about the average age of the study sample, which ranged from 5922 to 8312 years; the percentage of women ranged from 5%3 to 80%.18 Six of the seven US-based studies 3,5,9,10,16,20 provided data on race/ethnicity and the majority of subjects in those studies was Caucasian.

Assessment and magnitude of multimorbidity

The number of chronic conditions was assessed by simple counts of chronic conditions 3,5,9,10,12,14,16,18,20,21,22 (n=11), by combination of the Elixhauser and Charlson indices15 (n=1), and by the Charlson index alone 13, 17, 19 (n=3) (Table 2). The prevalence of chronic conditions ranged from at least one additional morbidity in 10%5 to 77%9 of persons; the frequency of four or more additional chronic conditions ranged from 5%9 to 60%.20 The most common morbidities considered were diabetes,3,18,20 chronic kidney disease,3,14,16,20,21 anemia,3,18, 21 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 3,20,21 and dementia/cognitive impairment. 3,16,20

Table 2.

Assessment of Multimorbidity

| Method | Assessment of MCCs | Data source | Prevalence of MCCS |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Count Of MCCs |

Simple count of acute-non-cardiac related conditions.5 | Medical records | Non-CVD related conditions prevalence: 7%. Most prevalent chronic conditions were: pneumonia (18%); gastrointestinal bleeding (16%) and stroke (10%).5 |

| Simple counts of non-CVD conditions12 | Medical records. | 57% of patients had at least one non-CVD related condition. Hypertension (80%); diabetes (34%); AMI (30%) and AF (22%) were the most prevalent MCCs.12 | |

| Simple counts of CVD-related conditions.9 | Medical records; physician’s progress notes | 17% of patients had 3 or + CVD-chronic conditions. Most common dyad of CVD related conditions was: hypertension and diabetes (12%).9 | |

| Simple counts of CVD and non-CVD related conditions.10 | Medical records. | 25% of patients had 4 or + cardiac and 16% had 2 or + non-cardiac related conditions. Hypertension (75%) and renal disease(22%) were the most prevalent morbidities.10 | |

| Simple counts of CVD related conditions.18 | Medical records; patient reports. | Most prevalent MCCs were: hypertension (90%); HF (49%); AF (45%) and diabetes (48%)18 | |

| Simple counts of CVD and Non-CVD related conditions.21 | Medical records. | Most prevalent CVD related conditions were previous AMI (34%); hypertension (25%); COPD (23%); AF (22%) and diabetes (16%)21 | |

| Simple count of non-CVD related conditions.3 | Electronic medical records; clinicians reports | Most prevalent conditions were: hypertension (70%); renal disease (49%); diabetes (45%); AF (35%); COPD (34%) and psychiatric disorders (28%).3 | |

| Simple counts of MCCs14 | Cardiovascular Research Network PRESERVE study. | Most prevalent chronic conditions were: hypertension (80%); hyperlipidemia (68%); COPD (42%) and AF (38%).14 | |

| Simple counts of MCCs.22 | Investigators’ case report forms | In SOLVD prevention 46% had 2 or + MCCs. In SOLVD treatment 60% patients had 2 or + MCCs. Most prevalent MCCs: diabetes (26% vs 15%) and chronic kidney disease (41% vs 26%) in the SOLVD prevention and treatment, respectively.22 | |

| Counts and clusters of MCCS.16 | Discharge records using AHRQ software. | Average number of MCCs: 7.5. Most prevalent morbidities were: hypertension (68%); renal disease (39%); COPD (36%); diabetes (34%); anemia (28%) and AMI (16%). 16 | |

| Counts of CVD and Non-CVD related conditions.20 | Medical records. | 60% of study sample had >3 MCCs. Hypertension (82%); diabetes (29%) and COPD (20%) were the most prevalent chronic conditions.20 | |

| Indexes | Charlson and Elixhauser scores.15 | Medical records. | Hypertension (49%); arrhythmias (35%) and HF (25%) were the most prevalent chronic condtions.15 |

| Charlson index.13 | Electronic database; medical records | Charlson score of > 6 presented in 13% of the study population. Most prevalent chronic conditions: AMI (60%); hypertension (54%); diabetes (48%); AF (31%) and COPD (22%).13 | |

| Charlson index.19 | Practitioner’s reports; hospital information system | Most prevalent MCCs were: hypertension (42%); AF (39%); COPD (27%); cognitive impairment (27%) and diabetes (27%).19 | |

| Charlson index.17 | Electronic database; medical records | 76% of study sample had 1morbidity. Most prevalent morbidities were: AF (46%); ACS (40%); COPD (38%); diabetes (36%); anemia (24%); and renal disease (19%). 17 |

Multimorbidity and clinical outcomes

All the studies reviewed found a positive association between the cumulative effect of multimorbidity and the risk of dying (Tables 3–6). Three studies reported a significant association between unspecified multimorbidity and long-term mortality.9,13,22 One study found a significant association between a score of four or more on the Charlson index and long-term mortality.19 Three studies found a significant association between number of morbidities and the hospital case fatality rate (CFR),5,10,12 and one study reported a significant association between a higher Charlson score and hospital CFR.15 As an example, of the positive association between number of morbidities and long term-mortality, one study found that in a cohort of 9,500 patients hospitalized due to an acute myocardial infarction, one-year mortality odds ratio (ORs) ranged from 1.16 (1.01; 1.34) to 2.31 (1.92; 2.78) for those presenting with one or four or more chronic conditions, respectively, as compared to those without any chronic conditions.9 Another study found that patients with heart failure and hypertension had a hazard ratio (HR) for death of 1.32 (1.12;1.54) and those presenting with heart failure and diabetes had a HR of 1.55 (1.28;1.88), as compared to those without these chronic conditions.22

Table 3.

Assessment of Outcomes and Limitations.

| Data source | Outcome Findings | Study Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term mortality | Medical records, death certificates at state and local divisions of vital Statistics.9 | 30-day and 1 year mortality HR increased proportionally with number of MCCs.(table 4 B) | Limited generalizability due to mostly white population. Potential misclassification, data on MCCs were abstracted from medical records without validation.9 |

| Electronic database; death certificates from department of health.13 | Number of MCCs was highly associated with the risk of non-sudden but not with sudden death.(table 4 B) | Limited generalizability: one ambulatory clinic included in study. Charlson index was calculated from data from medical records without validation.13 | |

| Medical records.18 | Risk of dying and hospitalizations was associated with the presence of diabetes and anemia, but not with hypotension. (table 4 C) | Small sample size. Only 3 chronic conditions were included in the study. Composite endpoint makes difficult to compare the impact of chronic conditions. No validation of outcomes.18 | |

| Danish Central Personal Registry.21 | Risk of dying was associated with the presence of diabetes, AF, COPD, anemia and chronic kidney disease. (table 4 B) | Limited generalizability due to the restricted criteria of the 2 RCTs. Study data outdated. Misclassification, no validation on MCCs data.21 | |

| 5 National VA databases.3 | Risk of dying was associated with the presence of diabetes, AF, COPD, anemia, liver disease, dementia and chronic kidney disease. (tables 4A, 4 B and 4 C) | Limited generalizability, 90% of the study sample were men from a VA. Potential misclassification due to data on non-CVD conditions and mortality were abstracted from electronic medical records without validation.3 | |

| Hospital medical records and practitioner’s reports.19 | Risk of dying was associated with a Charlson score of ≥4.(table 4 B) | Small sample size. No information on the distribution of MCCs in the study sample. Potential misclassification due to data on MCCs and mortality without validation.19 | |

| Death certificates, Social security files and hospital databases.14 | Risk of dying and hospitalization was significant for those with severe kidney disease. (tables 4 B and 4 C) | Potential misclassification due to data were collected without validation. Limited generalizability, only insured individuals were included in the study.14 | |

| Investigators’ data forms.22 | 4-year mortality HR increased proportionally with number of MCCs in both study participants. (tables 4 B and 4 C) | Outdated data (data were collected in early 90”s) Limited generalizability due to RCT with very restricted criteria.22 | |

| Medical records (unclear)20 | Risk of dying was associated with the presence of diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, depression, COPD, functional and cognitive impairment and chronic kidney disease. (table 4 B) | Potential misclassification due to the characteristics of the study design and no validation of MCCs or mortality. Data might be outdated (patients enrolled early 90’S follow-up ended in 2002).20 | |

| In-Hospital | Medical records, Social Security Death Master file.5 | Risk of dying was associated with the presence of MCCs. (table 4 A) | Potential missing data and misclassification due to abstraction of medical records without validation. Differential (longer) follow-up for those with -CVD related conditions.5 |

| Medical records15 | “Higher” scores on the Charlson and Elixhauser were associated with a higher risk of dying. (table 4 A) | Charlson and Elixhauser scores were calculated based on discharge data without validation. No data on study sample demographic characteristics, limited generalizability.15 | |

| Medical records12 | Mortality rates were higher in those with as compared to those without MCCs. (table 4 A) | Small sample size. Unclear how data on mortality was collected/validated. Data on comorbidities was abstracted from medical records without validation, potential misclassification.12 | |

| Medical records, death certificates at state and local divisions of vital Statistics. 10 | Mortality ORs increased proportionally with number of MCCs. (table 4 A) | Limited generalizability, mostly white patients from one geographic area. Potential misclassification due to data on MCCs without validation.10 | |

| Medical records.16 | Risk of dying was associated with the presence of a number of MCCs/Charlson score, or patient profile. (table 4 A) | Limited generalizability due to uses hospitalizations instead of patient as unit of analysis. Potential misclassification due to using administrative data without validation.16 | |

| Hospitalization | Medical records17 | Risk of hospitalization higher and lower quality of life (physical and emotional) in those with MCCs.(table 4 C) | Limited generalizability, only symptomatic patients were included in this study. No validation of the different “exposures”.17 |

Table 6.

Hospitalization Rates and Adjusted Analysis Findings (detailed)

| Hospitalization rates unadjusted |

MCCs counts | CVD related conditions | Non-CVD related conditions | Charlson/ Elixhauser |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) for those with: Severe kidney disease HF preserved EF:1.32 (1.24; 1.41) HF reduced EF 1.47 (1.35; 1.60)14 |

||||

| HR (95%CI) for those with: 1: 1.14 (0.95.1.75); 2 :1.47 (1.20;1.80); 3 : 1.66 (1.31;2.10); 4 or +: 2.09 (1.59;2.75)22 |

HR (95%CI) for those with: Hypertension:1.15 (1.06;1.25) Diabetes:1.31 (1.18;1.46)22 |

HR (95%CI) for those with: COPD:1.53 (1.30;1.80)22 |

||

| 40% at least 1 admission17 | Pearson correlation Charlson score 1:0.21 score 2: 0.16; score 3: 0.18; score 4 or +: 0.1817 |

|||

| For those with: HF preserved:50% HF reduced:49%3 |

||||

| Hospitalization + CFRs | ||||

| 24% with 1 admission18 | HR (95%CI) for those with: Diabetes: 1.76 (1.03; 3.00)18 |

HR (95%CI) for those with: Hypotension: 0.98 (0.97; 0.99); Anemia : 2.52 (1.32;5.05)18 |

||

Another study demonstrated a positive association between the number of morbidities and hospital case fatality rates (CFRs); the ORs ranged from 2.00 (95% confidence interval: 1.05, 3.82) to 2.80 (1.43, 5.49) in those patients with acute myocardial infarction and presenting with two or four or more chronic conditions, respectively, as compared to those without any morbidities.10 As an example of studies that examined the impact of specific chronic conditions on mortality, in a cohort of 5,275 patients that had experienced a previous hospitalization for an acute myocardial infarction, researchers reported ORs of 2.97(2.47, 3.56) for those with heart failure and ORs of 1.61(1.36; 1.93) for those with arrhythmias as compared to patients without these conditions.15

Of note, we identified only one study that reported on outcomes falling in to the category of “universal outcomes.”17 In a cohort of 628 patients with heart failure, the investigators found a statistically significant association between the overall burden of comorbidity, as assessed by the Charlson comorbidity index, and worse physical and emotional quality of life (Pearson’s correlation coefficients were reported for this analysis; for example, for emotional quality of life, the coefficient decreased from 0.16 in those with one to 0.04 in those with four chronic conditions based on the Charlson index.)17

Discussion

In this review, we found that there is a significant association between number and types of chronic conditions and the risk of dying; the most frequent morbidities examined were diabetes, chronic kidney disease, anemia, chronic pulmonary disease, and dementia/cognitive impairment. Whereas our findings highlight the very high prevalence of multimorbidity in patients with CVD, and the association of the cumulative effect of number of chronic conditions with outcomes such as mortality or the risk of rehospitalization, only very limited data are available on the magnitude and impact of multimorbidity on universal health outcomes such as symptom burden, functional capacity, and self-rated health among older adults with CVD.

Despite the high prevalence of CVD, and additional chronic conditions in these individuals, our findings suggest that there is a lack of consistency in the manner in which the burden of multimorbidity is assessed and characterized.3,5,10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 Although a number of different approaches exist for measuring multimorbidity, none of these is considered to be a “gold standard.” Simply counting morbidities is seemingly straightforward; however, this approach does not take into account the clinical severity of a condition or the varying impact across conditions. Comorbidity indices are relatively easy to apply, but may also lack sufficient specificity to adequately characterize the complexity of patients presenting with multimorbidity and CVD. Summary scores derived from various indices of multimorbidity can also be challenging to apply and integrate into clinical decision-making relevant to the care of individual patients.

Although the use of claims data to characterize multimorbidity in large populations in a ‘real-world’ setting may be highly efficient, these data are often inadequate to fully and accurately characterize the severity of disease and time of initial diagnosis of chronic conditions, and pose substantial challenges in addressing outcomes such as health-related quality of life, symptom burden, and function.

A relatively recent systematic review aimed to compare multimorbidity measures employing administrative data.23 The most common instrument used was the Charlson index, followed by the Elixhauser index. The authors concluded that “the performance of a given comorbidity measure depends on the patient group and outcome” being assessed.23 Future studies, combining data from claims databases and supplemented by other sources of data, such as electronic health records, may serve to improve our current understanding of the impact of multimorbidity on clinical outcomes in older adults with CVD.

The overarching aim of our review was to summarize findings from studies examining the association between the presence of multiple chronic conditions and clinical outcomes in patients with CVD. All the studies included in this review found a positive significant association between the burden of multimorbidity and short and long-term mortality. Although prior literature has suggested that multimorbidity plays an important role in quality of life and other universal health outcomes, in our review, only one study examined quality of life associated with the presence of multimorbidity.17

In 2011, the National Institute on Aging, in collaboration with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, convened an expert panel on health outcome measures for older persons with multimorbidity. The goal of this effort was to develop recommendations for the content of a core set of well-validated universal patient-centered outcome measures that could be routinely assessed in health care settings.24 Among the recommended health outcomes to be measured were: symptom burden, physical function and mobility, mental health outcomes, cognitive function, and social health outcomes. This expert panel concluded that universal outcome measures have emerged as a strong complement to disease-specific measures for comparative effectiveness research among older adults with multimorbidity.24 The panel also suggested that the routine assessment of these measures would facilitate meaningful and interpretable results that could be used by patients and providers to better communicate the balance between benefit versus risk of various interventions. Furthermore, another recent study evaluated function-related indicators in administrative claims data from the US Medicare beneficiaries with a hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction during 2007.25 The investigators suggested that an “expanded concept of general illness severity that incorporates indicators of potentially diminished functional status can better capture the heterogeneity of patients with multimorbidity.”25

A number of limitations of our review must be acknowledged. This review was limited to studies published in English. The extent to which our inability to review studies published in languages other than English affected our findings is unknown. Since our review included only peer-reviewed publications, there is a potential for introducing possible publication bias. Because we allowed for heterogeneity of the multimorbidity assessment measures included in this review, a quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Finally, since the majority of participants in the included studies were white, the generalizability of our findings to other race/ethnic groups may be limited. Future studies should examine potential racial and ethnic differences in the magnitude and impact of multimorbidity on clinical outcomes in patients presenting with CVD.

Conclusions

While multimorbidity is highly associated with the risk of dying in patients with CVD, there are only very limited data on the impact of multimorbidity on universal health outcomes (i.e., health related quality of life, symptom burden, and function). In addition, our review of the literature suggests a profound lack of consistency in the manner in which the burden of multimorbidity has been assessed and characterized across studies. Capturing the true complexity of older patients with CVD remains an ongoing challenge. Until that challenge is addressed, the value of available research on multimorbid patients with CVD for informing clinical decision-making is questionable.

Table 4.

In-Hospital CFRs (detailed)

| Hospital CFRs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude CFRs | Adjusted CFRs | |||||

| MCCs counts | CVD related conditions |

Non-CVD related conditions |

MCCs counts | CVD related conditions | Non-CVD related conditions |

Charlson/ Elixhauser |

| Patients with: 21% Patients w/o: 3%5 |

ORs(95%CI) for those with multimorbidity: 5.0 (3.3; 7.7)5 |

|||||

| MCCs+:17% MCCs-: 4%12 |

||||||

| 0: 3.7% 1: 6.1% 2: 10.6% 3: 11.2% 4 or +: 14.2%10 |

ORs (95%CI) for those with: 1: 1.31 (0.67; 2.57), 2: 2.00 (1.05; 3.82); 3: 2.14 (1.10; 4.20); 4 or +: 2.80 (1.43; 5.49).10 |

ORs (95%CI) for those with: 1: 1.24 (1.03;1.50); 2: 1.63 (1.12; 2.37); 3 or +:1.76 (1.11; 2.78) 10 |

||||

| RR (95%CI): for those with 7 or + MCCs: 1.03 (1.02;1.04)16 |

RR (95%CI) Charlson score of 5 or +: 1.16 (1.08;1.25)16 |

|||||

| ORs (95%CI) for those with: HF: 2.97 (2.47;3.56) Arrhythmias: 1.61 (1.36;1.93)15 |

High Elixhauser score ≥2.4: ORs: 1.14 (1.07; 1.22)15 |

|||||

| For those with: HF preserved: 20% HF reduced: 25%3 |

||||||

Table 5.

Long-term CFRs (detailed)

| MCCs counts | CVD related conditions | Non-CVD related conditions | Charlson/ Elixhauser |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day ORs for those with: 1: 1.19 (0.93;1.35); 2: 1.49 (1.23;1.80); 3 : 1.64 (1.32;2.03); 4 or + :1.68 (1.28;2.21); 1-year ORs for those with: 1: 1.16 (1.01;1.34); 2: 1.62 (1.41;1.87); 3: 1.94 (1.66;2.26); 4 or + : 2.31 (1.91;2.78)9 |

HR (95%CI) for those with: Hypertension+diabetes 30-day: 1.09 (0.85;1.39) Hypertension+diabetes 1-year: 1.27 (1.06;1.50)9 |

||

| HR (95%CI) for those with: AF:1.30 (1.06; 1.60); Diabetes: 1.31 (1.01; 1.61) 21 |

HR (95%CI) for those with: COPD:1.46 (1.37;1.55); Anemia: 1.29 (1.13;1.48); Chronic kidney disease: 1.36 (1.13;1.63)21 |

||

| HR (95%CI) for those with severe kidney disease: HF preserved EF: 1.67 (1.41; 1.76); HF reduced EF 2.15 (1.87; 2.48).14 |

|||

| (4-year) mortality ORs for those with: 1:1.48 (1.10;2.00); 2: 2.02 (1.43;2.85); 3: 2.80 (1.85;4.22); 4or +: 4.95 (3.02;8.11)22 |

HR (95% CI) for those with: Hypertension: 1.32 (1.12;1.54) Diabetes: 1.55 (1.28;1.88)22 |

HR (95% CI) for those with: COPD:1.73 (1.30;2.31)22 |

|

| 3-year HR (95% CI) for those with Charlson score of 3–4 : 1.5 (0.7;2.9); Charlson score of 4 or + 4.0 (1.9;8.8) (1–2 score-referent group)19 |

|||

| HR (95% CI) for those with: Charlson score ≥4: Non-sudden death: 2.78 (2.09;3.70); Sudden death: 0.49 (0.19; 1.28).13 |

|||

| HR (95%CI) for those with: Chronic kidney disease: HF preserved: 1.28 (1.07;1.53) HF restricted EF 1.25 (1.12; 1.38); Anemia: HF preserved:1.35 (1.13;1.61) HF restricted EF: 1.42 (1.28; 1.57), |

|||

| COPD: HF preserved:1.61 (1.36;1.91) HF restricted EF: 1.23 (1.11; 1.37), Liver disease: HF preserved :2.31 (1.48;3.62) HF restricted EF: 1.41 (1.05; 1.89); dementia : HF preserved:1.75 (1.21; 2.51) HF restricted EF: 1.48 (1.16; 1.90).3 |

|||

| HR (95%CI) for those with: Diabetes: 1.64 (1.33; 2.03), Cerebrovascular disease: 1.53 (1.22;1.92)20 |

HR (95%CI) for those with: Chronic kidney disease:1.32 (1.07;1.62) Depression :1.44 (1.09;1.90), Functional impairment: 1.30 (1.04;1.63), Cognitive impairment: 1.33 (1.02; 1.73).20 |

Key points.

Multimorbidity is highly prevalent in older adults with cardiovascular disease and is related to higher levels of healthcare use and mortality.

There are inconsistencies in the manner in which multimorbidity has been characterized in older adults presenting with cardiovascular disease.

Limited data exist on the impact of multimorbidity on universal health outcomes (e.g.; health related quality of life, symptom burden, and function) in older adults with cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Gurwitz and Tisminetzky are supported by award number: 1R24AG045050 from the National Institute of Aging, Advancing Geriatrics Infrastructure & Network Growth (AGING). Partial salary support was provided to Dr. Goldberg by National Institutes of Health Grant 1U01HL105268–01 and R01 HL35434.

Appendix 1

MEDLINE Search Strategy

| Search | String |

|---|---|

| #1 | Cardiovascular disease [title/abstract] |

| #2 | Myocardial infarction [title/abstract] |

| #3 | Heart failure [title/abstract] |

| #4 | # 1 OR #2 OR #3 |

| #5 | Comorbidities [title/abstract] |

| #6 | Multimorbidity [title/abstract] |

| #7 | Multiple chronic conditions [title/abstract] |

| #8 | #5 OR #6 OR #7 |

| #9 | Clinical outcomes [title/abstract] |

| #10 | Mortality [title/abstract] |

| #11 | Hospital readmission [title/abstract] |

| #12 | Rehospitalization [title/abstract] |

| #13 | #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 |

| #14 | # 4 AND # 8 AND #13 |

| #15 | #14 AND full text[sb] AND "last 10 years"[PDat] AND Humans |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Contributor Information

Mayra Tisminetzky, Email: Mayra.Tisminetzky@umassmed.edu.

Robert Goldberg, Email: Robert.Goldberg@umassmed.edu.

Jerry H. Gurwitz, Email: Jerry.Gurwitz@umassmed.edu.

References

- 1.FASTSTATS - Heart Disease. [Page last reviewed: August 9, 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/heart.htm.

- 2.Saczynski JS, Go AS, Magid DJ, et al. Patterns of Comorbidity in Older Patients with Heart Failure: The Cardiovascular Research Network PRESERVE Study. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2013;61(1):26–33. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, et al. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(11):998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple Chronic Conditions: Prevalence, Health Consequences, and Implications for Quality, Care Management, and Costs. J Gen Intern Medicine. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtman JH, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al. Acute noncardiac conditions and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1925–1930. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.722090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ani C, Pan D, Martins D, et al. Age- and sex-specific in-hospital mortality after myocardial infarction in routine clinical practice. Cardiol Res Pract. 2010;2010:752–765. doi: 10.4061/2010/752765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G, et al. Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(7):1226–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachdev M, Sun JL, Tsiatis AA, et al. The prognostic importance of comorbidity for mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(4):576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McManus DD, Nguyen HL, Tisminetzky M, et al. Multiple cardiovascular comorbidities and acute myocardial infarction: temporal trends (1990–2007) and impact on death rates at 30 days and 1 year. Clinical Epidemiology. 2012;4:115–123. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S30883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H-Y, Saczynski JS, McManus DD, et al. The impact of cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities on the short-term outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Clinical Epidemiology. 2013;5:439–448. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S49485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd CM, Leff B, Wolff JL, et al. Informing clinical practice guideline development and implementation: prevalence of coexisting conditions among adults with coronary heart disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(5):797–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piçarra BC, Santos AR, Celeiro M, et al. Non-cardiac comorbidities in the very elderly with acute myocardial infarction: prevalence and influence on management and in-hospital mortality. Rev Port Cardiol. 2011;30(4):379–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke B, Howlett J, Sapp J, et al. The effect of comorbidity on the competing risk of sudden and nonsudden death in an ambulatory heart failure population. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(2):254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DH, Thorp ML, Gurwitz JH, et al. Chronic kidney disease and outcomes in heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction: the Cardiovascular Research Network PRESERVE Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(3):333–342. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gili M, Sala J, López J, et al. Impact of comorbidities on in-hospital mortality from acute myocardial infarction, 2003–2009. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011;64(12):1130–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CS, Chien CV, Bidwell JT, et al. Comorbidity profiles and inpatient outcomes during hospitalization for heart failure: an analysis of the U.S. Nationwide inpatient sample. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:73–82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buck HG, Dickson VV, Fida R, et al. Predictors of hospitalization and quality of life in heart failure: A model of comorbidity, self-efficacy and self-care. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.06.018. S0020–7489: 00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maréchaux S, Six-Carpentier MM, Bouabdallaoui N, et al. Prognostic importance of comorbidities in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart Vessels. 2011;26(3):313–320. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oudejans I, Mosterd A, Zuithoff NP, et al. Comorbidity drives mortality in newly diagnosed heart failure: a study among geriatric outpatients. J Card Fail. 2012;18(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murad K, Goff DC, Jr, Morgan TM, et al. Burden of Comorbidities and Functional and Cognitive Impairments in Elderly Patients at the Initial Diagnosis of Heart Failure and Their Impact on Total Mortality: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(7):542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mogensen UM, Ersbøll M, Andersen M, et al. Clinical characteristics and major comorbidities in heart failure patients more than 85 years of age compared with younger age groups. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(11):1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böhm M, Pogue J, Kindermann I, et al. Effect of comorbidities on outcomes and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor effects in patients with predominantly left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(3):325–333. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1109–1118. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Working group on health outcomes for older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Universal health outcome measures for older persons with multiple chronic conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2333–2341. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chrischilles E, Schneider K, Wilwert J, et al. Beyond comorbidity: expanding the definition and measurement of complexity among older adults using administrative claims data. Med Care. 2014;(Suppl 3):S75–S84. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]