Abstract

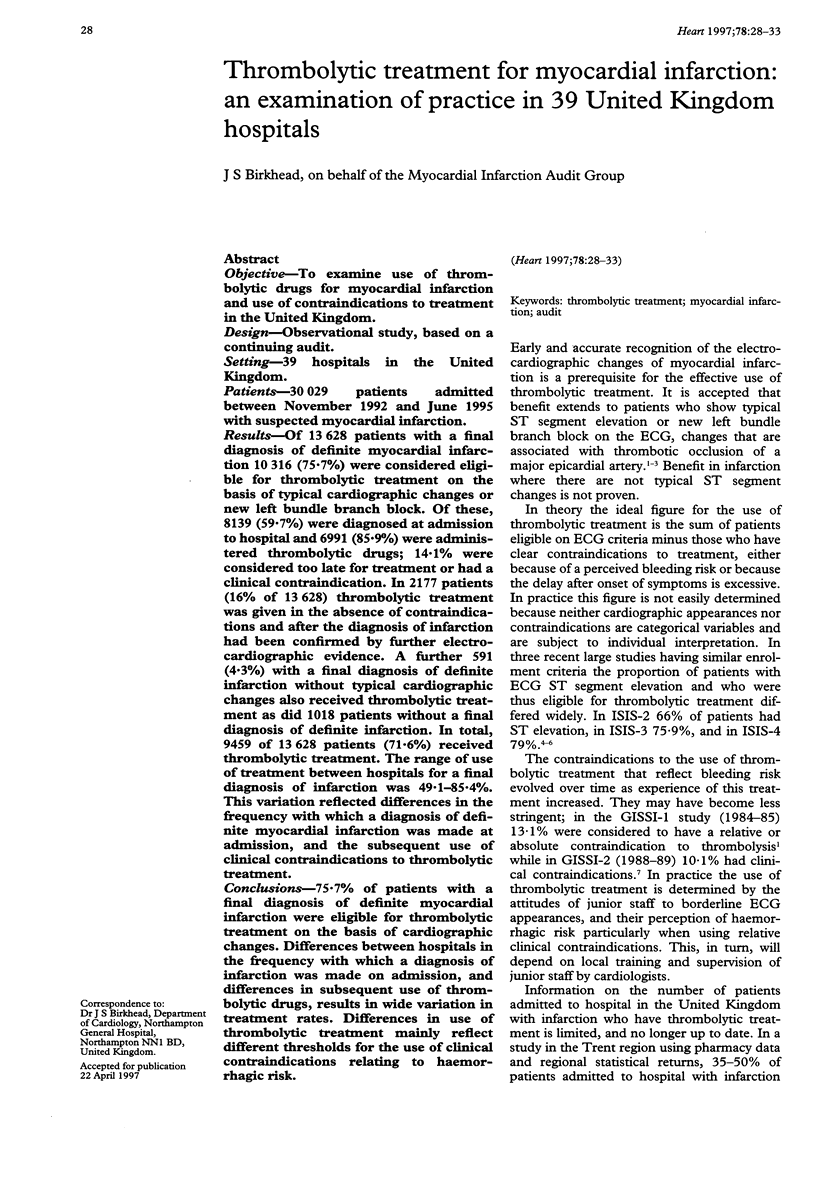

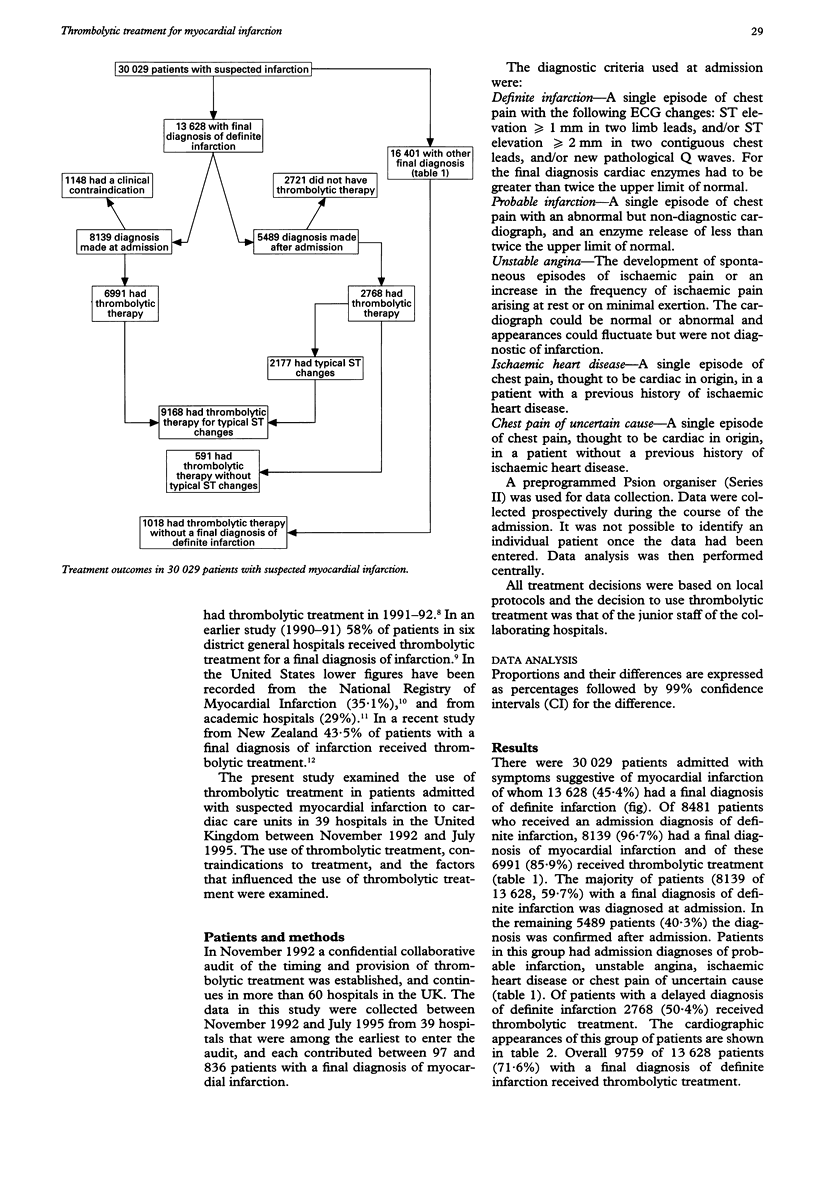

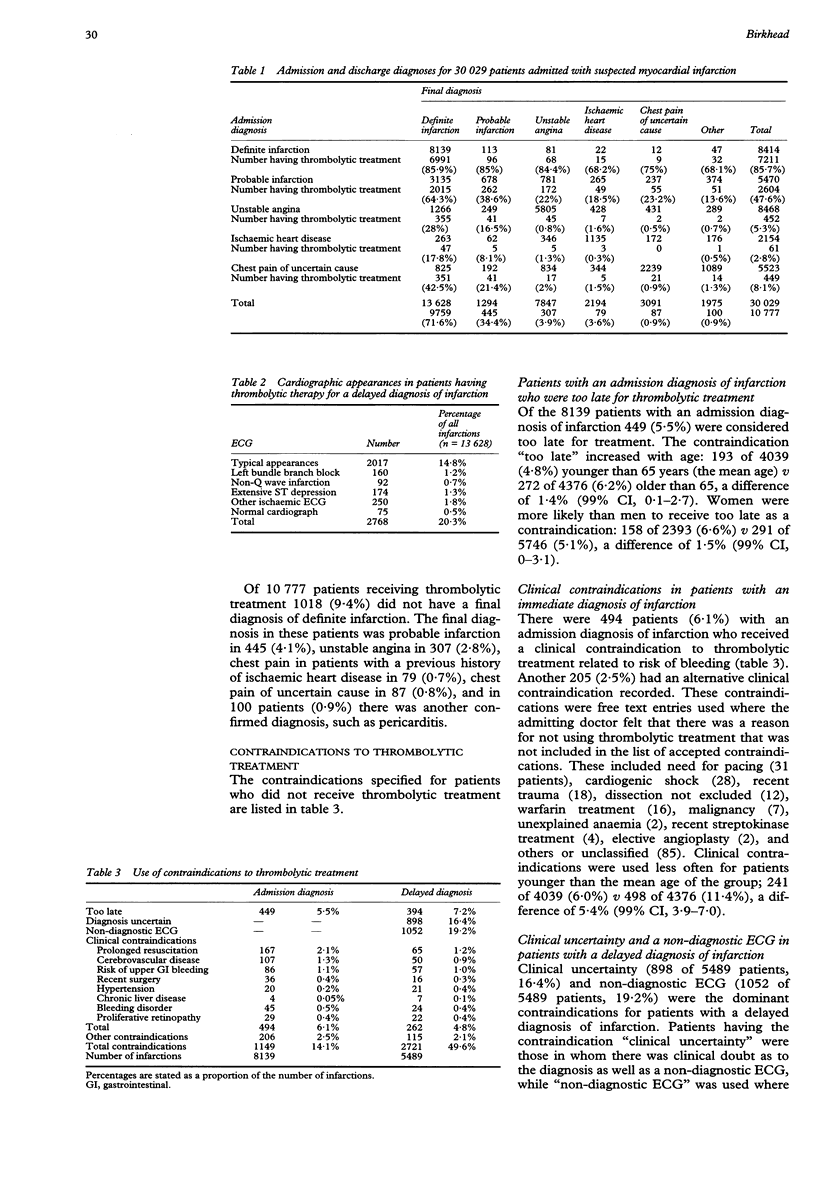

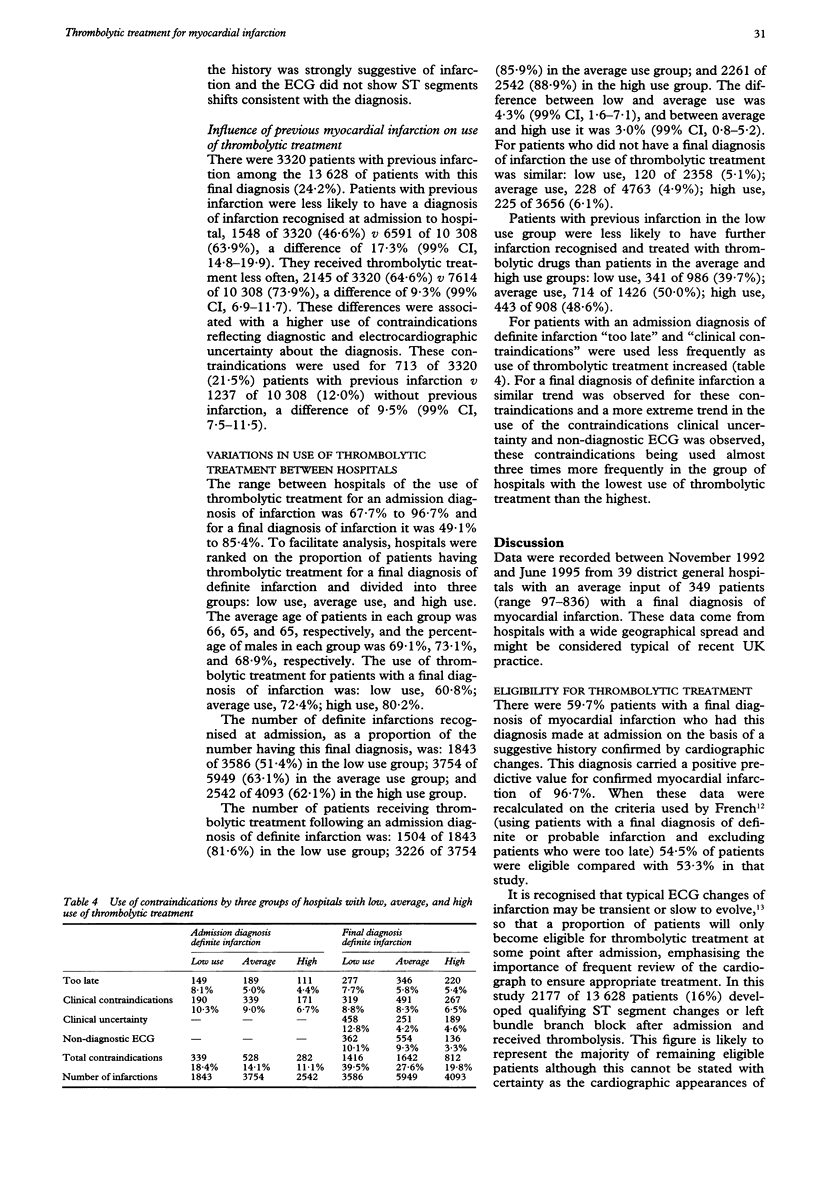

OBJECTIVE: To examine use of thrombolytic drugs for myocardial infarction and use of contraindications to treatment in the United Kingdom. DESIGN: Observational study, based on a continuing audit. SETTING: 39 hospitals in the United Kingdom. PATIENTS: 30,029 patients admitted between November 1992 and June 1995 with suspected myocardial infarction. RESULTS: Of 13,628 patients with a final diagnosis of definite myocardial infarction 10,316 (75.7%) were considered eligible for thrombolytic treatment on the basis of typical cardiographic changes or new left bundle branch block. Of these, 8139 (59.7%) were diagnosed at admission to hospital and 6991 (85.9%) were administered thrombolytic drugs; 14.1% were considered too late for treatment or had a clinical contraindication. In 2177 patients (16% of 13,628)-thrombolytic treatment was given in the absence of contraindications and after the diagnosis of infarction had been confirmed by further electrocardiographic evidence. A further 591 (4.3%) with a final diagnosis of definite infarction without typical cardiographic changes also received thrombolytic treatment as did 1018 patients without a final diagnosis of definite infarction. In total, 9459 of 13,628 patients (71.6%) received thrombolytic treatment. The range of use of treatment between hospitals for a final diagnosis of infarction was 49.1-85.4%. This variation reflected differences in the frequency with which a diagnosis of definite myocardial infarction was made at admission, and the subsequent use of clinical contraindications to thrombolytic treatment. CONCLUSIONS: 75.7% of patients with a final diagnosis of definite myocardial infarction were eligible for thrombolytic treatment on the basis of cardiographic changes. Differences between hospitals in the frequency with which a diagnosis of infarction was made on admission, and differences in subsequent use of thrombolytic drugs, results in wide variation in treatment rates. Differences in use of thrombolytic treatment mainly reflect different thresholds for the use of clinical contraindications relating to haemorrhagic risk.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams J., Trent R., Rawles J. Earliest electrocardiographic evidence of myocardial infarction: implications for thrombolytic treatment. The GREAT Group. BMJ. 1993 Aug 14;307(6901):409–413. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6901.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronow W. S. Prevalence of presenting symptoms of recognized acute myocardial infarction and of unrecognized healed myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Am J Cardiol. 1987 Nov 15;60(14):1182–1182. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkhead J. S. Time delays in provision of thrombolytic treatment in six district hospitals. Joint Audit Committee of the British Cardiac Society and a Cardiology Committee of Royal College of Physicians of London. BMJ. 1992 Aug 22;305(6851):445–448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6851.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French J. K., Williams B. F., Hart H. H., Wyatt S., Poole J. E., Ingram C., Ellis C. J., Williams M. G., White H. D. Prospective evaluation of eligibility for thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1996 Jun 29;312(7047):1637–1641. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlson B. W., Herlitz J., Hartford M. Prognosis in myocardial infarction in relation to gender. Am Heart J. 1994 Sep;128(3):477–483. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketley D., Woods K. L. Impact of clinical trials on clinical practice: example of thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1993 Oct 9;342(8876):891–894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91945-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. S., Cross S. J., Rawles J. M., Jennings K. P. Patients with suspected myocardial infarction who present with ST depression. Lancet. 1993 Nov 13;342(8881):1204–1207. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92186-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips B. G., Yim J. M., Brown E. J., Jr, Bittar N., Hoon T. J., Celestin C., Vlasses P. H., Bauman J. L. Pharmacologic profile of survivors of acute myocardial infarction at United States academic hospitals. Am Heart J. 1996 May;131(5):872–878. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers W. J., Bowlby L. J., Chandra N. C., French W. J., Gore J. M., Lambrew C. T., Rubison R. M., Tiefenbrunn A. J., Weaver W. D. Treatment of myocardial infarction in the United States (1990 to 1993). Observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 1994 Oct;90(4):2103–2114. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]