Abstract

We examine the ethical, social and regulatory barriers that may hamper research on therapeutic potential of certain controversial controlled substances like marijuana, heroin or ketamine. Hazards for individuals and society, and their potential adverse effects on communities may be good reasons for limiting access and justify careful monitoring of certain substances. Overly strict regulations, fear of legal consequences, stigma associated with abuse and populations using illicit drugs, and lack of funding may hinder research on their considerable therapeutic potential. We review the surprisingly sparse literature and address the particular ethical concerns of undue inducement, informed consent, risk to participants, researchers and institutions, justice and liberty germane to the research with illicit and addictive substances. We debate the disparate research stakeholder perspectives and why they are likely to be infected with bias. We propose an empirical research agenda to provide a more evidentiary basis for ethical reasoning.

An ethical exploration of barriers to research on controlled drugs

Federal and State agencies have powerful and important justifications for controlling access to substances that are potentially dangerous. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) controls drugs associated with a high risk of abuse (DEA 2007). Certain drugs can cause addiction and may induce or exacerbate underlying mental illness. These hazards for individuals and society, and their potential adverse effects on communities, are good reasons for limiting access and justify careful monitoring of their use. At the same time, the absence of studies on therapeutic uses of these controlled drugs suggests that strict regulations, fear of legal consequences, stigma associated with abuse and populations using illicit drugs, and lack of funding may hinder research on their therapeutic potential. These impediments can create barriers to developing effective medications to alleviate chronic suffering and exploring harm reduction (Abrams 1998). They could obstruct research that might advance the treatment of chronic conditions or possibly have an impact on the disease itself.

For the purpose of explaining the issues, we will focus on HIV as our illustrative example because it shows the complexity of designing ethical approaches for research on controlled substances. For HIV+ populations, the risks associated with drug use also include the spread of infection through shared syringes, interactions with prescribed medicines (Harrington 1999), and side effects such as depression (Kousik 2012). Psychotropic drugs can diminish decisional capacity and lead to increased risk-taking, which in turn can lead to HIV transmission (Klitzman 2006).

Chronic pain for people living with HIV is frequent, devastating, and potentially difficult to treat. Chronic pain affects 1/3 of the HIV+ population and amounts to a significant disease burden (Ghosh 2012). Heroin, marijuana and many other illegal drugs are effective analgesics, some prescribed routinely in Europe (Wee 2014). We tabulate their current routine clinical and the supporting clinical evidence (Table 1: Therapeutic potential of certain controlled substances). For many people living with HIV, chronic pain persists despite attempts at management with opioids, NSAID, anti-inflammatory agents, tricyclic antidepressants and pain modifying therapies (Finnerup 2010). In addition to pain, HIV+ patients endure multiple chronic systemic, neurological, oral, respiratory, musculoskeletal, ophthalmological, dermatological, genitourinary, and psychological symptoms (Robertson 2014; Giles 2009). Taken together, we are sympathetic to the suffering of people living with these chronic symptoms cries out for relief. For this reason, research on effective and compassionate management of HIV-related symptoms and anti-retroviral drug side-effects should be a biomedical research priority, even if the potential treatment agents include controlled substances.

Table 1.

Therapeutic potential of certain controlled substances

| Drug | Schedule | Clinical Evidence Supporting Therapeutic Use | Routine Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diamorphine (aka heroin) | I (US) | Labor pain (McInnes 2004; Wee 2011; Wee 2014), pediatric acute pain (Gossop 2005; Kendall 2001; Mondzac 1984), pulmonary edema, myocardial infarct (Gossop 2005) | UK |

| Ketamine (aka special K) | I (CAN) III (US) |

Anesthesia and analgesia for adults and children (Elia 2005; Roback 2006), chronic pain (Sawynok 2014), major depression and other mental illnesses (Kavalali 2012; Li 2011) | US, Europe and other jurisdictions |

| Ibogaine | I (US) | Addiction interrupter (Alper 1999; Antonio 2013; Koenig 2014), depression (Bulling 2012), anti-HIV (Silva 2004) | None to date |

| Cocaine (aka snow) | II (US) | Anesthesiology and ophthalmology (Fleming 1990; Yau 2011) | US, Europe |

| Marijuana (aka cannabis) | I (US) | Neuropathic pain (Abrams 2007; Ellis 2009; Iskedjian 2007; Lynch 2011; Ware 2010; Wilsey 2013), refractory epilepsy (Hamerle 2014), MS related spasticity (Koppel 2014), appetite stimulation (Kramer 2014; Lutge 2013), dementia, diabetes, glaucoma, anti-HIV (Costantino 2012) | Some US states Europe and other jurisdictions |

| LSD, ecstasy, amphetamines | I (US) | Trauma, depression and other psychological disorders (Greer 1986; Jacobson 2014; Parrott 2007; Ross 2012; Sessa 2007), addiction treatment (Castells 2010; Nuijten 2014) | None to date |

Therapeutic use of certain controversial controlled substances: Unbeknownst to many, certain controversial controlled substances (e.g. heroin and cocaine) are routinely prescribed in many jurisdictions, others have considerable therapeutic potential (Ibogaine, ketamine, ecstasy). This table lists several controversial substances and contrasts their current DEA s with the clinical evidence for therapeutic potential and current routine clinical use.

Drug use and HIV transmission are intimately connected, because of the high prevalence of drug use in some high risk HIV+ subpopulations, it is important to address the negative effects associated with illicit drug use (Lancet 2012). Developing effective treatments for pain and other symptoms associated with chronic HIV could reduce the problematic use of less effective and illicit drugs, and reduce the associated harm of HIV transmission.

The Therapeutic Potential of Controlled Drugs

The abuse potential of the strongest analgesics has led the Federal government to tightly control certain drugs. The DEA defines a Schedule I drug as having “no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States” (DEA 2007). Scheduled drugs include highly controversial, illicit or tightly “controlled drugs” like cocaine (Schedule II) and ketamine (Schedule III) some of which may have considerable therapeutic potential (Table 1: Therapeutic potential of certain controlled substances). While any controlled drug can be dangerous, even the most abused and controversial drugs may have legitimate therapeutic indications; The decision to place a drug on any of these schedules is currently rather arbitrary, which is why we include all controversial controlled drugs in our discussion but focus on the most controversial substances1.

Their considerable therapeutic potential explains why many tightly controlled and controversial drugs are widely used in clinical practice inside and outside of the U.S. (Table 1: Therapeutic potential of certain controlled substances).

Heroin, marijuana, ketamine and cocaine have shown therapeutic benefit in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews (Ellis 2009; Kendall 2001; Koppel 2014; McInnes 2004; Roback 2006; Ware 2010; Wee 2011; Wee 2014). Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses found smoked marijuana to be equally or more effective for HIV-related chronic neuropathic pain than conventionally prescribed alternatives like gabapentin (Abrams 2007; Ellis 2009; Ware 2010; Wilsey 2013). Marijuana may also have therapeutic uses in appetite stimulation and nausea reduction, symptoms frequently experienced by people living with HIV (Giles 2009).Marijuana may enhance appetite, reduce nausea and prevent wasting (Kramer 2014) and may help in refractory epilepsy (Hamerle 2014). Evidence from randomized trials suggest that ketamine is effective as an adjuvant therapy in the prevention and treatment of acute and chronic pain, and RCTs now also support its use in children (Elia 2005; Roback 2006; Sawynok 2014). Ketamine may also have therapeutic use for major depression (Kavalali 2012; Li 2011). Ibogaine and other serotonergic hallucinogens may act as addiction interrupters (Alper 1999; Antonio 2013; Donnelly 2011; Koenig 2014) anti-depressive (Bulling 2012) and even anti-HIV medication (Silva 2004). Heroin is widely prescribed in the British National Health Service for pain associated with both acute and chronic conditions (Gossop 2005), even in children and woman in labor (Kendall 2001; McInnes 2004; Mondzac 1984; Wee 2011; Wee 2014). Ecstasy and LSD may have therapeutic benefits for a wide range of conditions including trauma, depression and other psychological disorders (Degenhardt 2010; Greer 1986; Parrott 2007; Sessa 2007); depression is common and insidious in the HIV+ population (Giles 2009). The class of psychostimulant drugs may be effective in addiction interruption (Castells 2010; Nuijten 2014). Cocaine is routinely used in anesthesiology and ophthalmology (Fleming 1990; Yau 2011). There is laboratory evidence that ibogaine and cannabinoid drugs can interfere with HIV replication (Silva 2004; Costantino 2012), motivating the Cochrane Collaboration to study the medical use of marijuana for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS (Lutge 2013). These therapeutic effects should be studied more systematically and thoroughly. However, we can learn about the therapeutic benefit of controlled drugs only if we study them.

Brief history of heroin and marijuana regulation in the Anglo-Saxon world

The legal status of marijuana is uncertain, in flux, and varies across the U.S. and sometimes varies even within a state or county (Bostwick 2012, Aggarwal 2009). In the U.S., drugs of abuse are currently regulated according to Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (1970), known as the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) (DEA 2007). CSA outlines federal guidelines for drug classification. Schedule I substances (including marijuana and heroin) are defined as having the “highest potential for abuse”, “no currently accepted medical use,” and as not having “accepted safety for use under medical supervision” (DEA 2007). Classification under Schedule I is rarely based on scientific evidence alone (Cohen 2009a). Heroin and marijuana policy are a case in point, and contrasting the history of heroin and marijuana regulation in the U.S. and the U.K. can be instructive (Berridge 2009; Aggarwal,2009).

In the U.S., very few clinical studies have investigated the therapeutic potential of heroin, while in the U.K. heroin's therapeutic use has and continues to be actively studied (Oviedo-Joekes 2009; Wee 2014). Early in the 20th century, as an unlisted ingredient in several effective over-the-counter medicines, heroin quickly grew notorious for its addictive potential. It was then associated with leading middle-class Americans unwittingly to ruin (United States Congress 1980). In response, and as part of an international effort to control the flow of opium and also enhance Sino-American relations (McAllister 2004), the U.S. initiated measures to limit the manufacture, importation, and prescription of opium with the Harrison Narcotics Act in 1914. The Act succeeded in removing heroin from the consumer market, but an uptick in violent street crime ensued and was ascribed to heroin's thriving on the black market. In the wake of alcohol prohibition, Congress also passed a law prohibiting the importation of opium in 1924 (United States Congress 1980). Very little changed in U.S. drug policy until the Controlled Substances Act was passed in 1970.

In contrast, the U.K. restricted and controlled access to heroin, but continued to allow its therapeutic use when prescribed by physicians (United States Congress 1980). In 1920, the British government passed the Dangerous Drugs Act, which, like the U.S. Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914, unilaterally restricted clinicians’ access to heroin by making it a crime to possess, import, export, or manufacture opium without a license (Zinberg 1972). Crucially, however, in 1926 the U.K. allowed narcotics, including heroin, to be prescribed as routine therapy. Since then, and to this day, heroin (under the name of diamorphine) continues to be on the national formulary of the U.K. (May 1972). This policy has enabled physicians to exercise their clinical judgment in prescribing heroin and explore its therapeutic potential (Gossop 2005). Initially, indications in the U.K. were limited to treatment for narcotic addiction, pain relief after an attempt at cure has failed, and prescriptions for small doses to enable helpless handicapped patients to perform tasks of daily living. Research has supported heroin's expanded uses. In the UK today, heroin is routinely administered to control labor pain (McInnes 2004; Wee 2011; Wee 2014) and for pain control after myocardial infarction; it is nasally administered in children to control acute pain (Kendall 2001), used for routine pain control in critically ill adults, relief of pulmonary congestion, and symptom relief for shortness of breath for patients with pulmonary edema. In 1967 the British Parliament amended the Dangerous Drug Act to include preventative measures against addiction, such as modifications in prescription writing practices and the establishment of punishment for physicians who violated these restrictions (Zinberg 1972). Subsequently those limitations were bolstered by the Misuse of Drugs Bill of 1971, which allowed the government to add or remove drugs in any class of the drug scheduling system. Through all of these legislative efforts, the U.K. approach has focused on facilitating safe, clinical use of heroin. Even though U.K. policy appears to be more informed by evidence than U.S. policy, it too has been criticized for grouping drugs in classes equivalent to U.S. Schedule I and hampering therapeutic use and research (Berridge 2009).

A similar approach of blanket prohibition has characterized recent U.S. policy on marijuana. Marijuana was on the US formulary until 1937 (Aggarwal 2009). Throughout the 1930s, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics closely monitored marijuana use in public settings (Matchette 1995), and newspaper articles dramatized the dangers of marijuana (Erleywine 2005). Federal Bureau of Narcotics Commissioner, Harry J. Anslinger, presented sensationalized newspaper clippings as proof of the harms of marijuana. Congress responded with the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 (Erleywine 2005). The Tax Act required marijuana distributors, including physicians, to pay a prohibitively high tax on each of their transactions with the drug. At the time, the American Medical Association disapproved of the Act, and in a statement before Congress, their consultant, Dr. William C. Woodward, testified against the inflammatory and dubious anecdotal evidence used to support the Marijuana Tax Act (Musto 1972). Woodward advocated unsuccessfully for the inclusion of marijuana under the Harrison Act of 1914 instead. Such a policy would have limited the use and production of the drug, while still making it possible for clinicians to prescribe it. The passage of Marijuana Tax Act was followed in 1951 by the Boggs Act which imposed and increased minimum sentencing for all drug violations. The idea behind mandatory minimums was that imposing harsh punishment for the use or possession of mild “gateway” drugs, like Marijuana would discourage use of stronger drugs and thereby forestall addiction (Swartz 2012). During Lyndon Johnson's presidency a special presidential committee was unable to confirm or refute the claim that marijuana use led to violence or heroin addiction (Erleywine 2005), but the regulations have remained in place and the Controlled Substances Act was passed in 1970. These views may incorporate attitudes towards racial minorities, our society's support of the “war on drugs,” fears of addiction, and stereotypes of PWID or use recreational substances (Nahas 1974; Grinspoon 1995). In addition, enforcement of drug laws appears to target racial minorities and socially stigmatized groups (Alexander 2010).

The call for reform

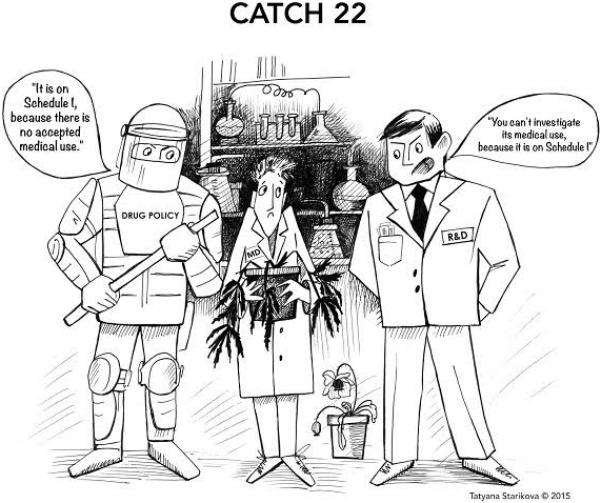

Since these regulations have been in place, scientists and journalists have repeatedly questioned the U.S. drug scheduling system. As recently as June 2014, investigators writing in the New England Journal of Medicine complained of a lack of data about the adverse effects of marijuana use (Volkow 2014). We and they noted the “Catch-22” of U.S. drug policy which defines marijuana as having no “accepted medical use” while obstructing efforts to investigate whether or not it actually has medical uses. (Honan 2013; Heuvel 2013; Keefe 2013) In the same vein, editors at Scientific American repeatedly called U.S. marijuana regulation policy “outdated” and pronounced that it “thwarts legitimate research” (Scientific American 2004), and editors at Nature implored researchers to “prioritize research on [marijuana]” (Nature Neuroscience 2014). Recently, a series of critics have made similar points. Joseph S. Albert, pointed out that “[m]uch of what we know about cannabis comes from folktales and limited clinical observation” (Elsevier.com 2015). As part of an editorial series on marijuana legalization, The New York Times cited “the clear consensus of science that marijuana is far less harmful to human health than other banned drugs” (Boffery 2014); the Gainesville Sun editorial board, in its editorial “Allow Pot Research,” wrote that “cannabis research is thin” due to “onerous federal restrictions” (Gainesville Sun 2015); and The Washington Post reported on U.S. veterans’ attempts to convince the Department of Veteran's Affairs of the legitimacy of marijuana as a treatment option (Wax-Thibodeaux 2014). All of these articles demanded evidenced-based evaluations of the benefits and harms of controlled substance regulations and the U.S. drug scheduling system itself. In sum, these critical assessments point out that across the U.S. people are talking about medical marijuana, but nobody knows what it's good for.

Catch 22

The limited guidance on using regulated drugs for treatment of pain associated with HIV is typically not evidence-based and often politically biased (Andreae 2012; Bostwick 2012). The result is a classic Catch-22 situation (Figure 1) (Diep 2011; Jacobson 2014). There is scant evidence on the therapeutic effectiveness of controlled substances for the treatment of HIV symptoms, because there are few studies: There are few studies of the effectiveness of these drugs because they are tightly regulated and considered to lack medical benefit.

Figure 1.

Catch 22 Cartoon

Systematic and thorough research on controlled drugs has the potential to provide patients living with HIV with therapeutic benefit as treatment of chronic disease-related symptoms. Beyond this promise, studies can also produce significant harm reduction. Because many chronic pain patients self-medicate and self-manage their pain outside the health care system, information from studies would help to avoid overuse and misuse of ineffective drugs and the self-medication misuse of illicit drugs. Better prevention or treatment of addiction would curtail the secondary harm, including the spread of HIV disease. Increased knowledge about therapeutic benefit of substances currently classified as Schedule I, II, or III could lead to improved treatment options for HIV+ patients and thus reduce their abuse of inefficient or illegal alternatives. Information from studies of these drugs could reduce cost burdens on the health care system by promoting the prescription of effective treatments, reducing inappropriate drug use, optimizing and integrating indicated administration of controlled substances, and avoiding the untoward societal effects associated with illegal drug use. Some argue that many controlled drugs would be significantly cheaper if legal and more accessible for resource-poor populations (Kilmer 2010; Blackstone 2012) Furthermore, scientific information on the effectiveness of controlled drugs as treatment could reduce the stigma associated with their use. That information could, in turn, reduce the stigmatization of those who use the drugs and, thereby enhance their opportunities for gainful employment and meaningful social participation (Bottorff 2013).

Social and Ethical Barriers to Studies that Administer Controlled Drugs

Many people in our society, including people who review studies, seem to have developed attitudes about substances such as marijuana, ketamine, and heroin. These views may incorporate attitudes towards racial minorities, support of the “war on drugs,” fears of addiction, and stereotypes of drug users and addicts. Such views expressed in laws, rules, and regulations may have the effect of impeding research on controlled drugs (Abrams 1998; Anderson 2012b; Bernard 2006; Fleming 1990; Bottorff 2013; Bulling 2012; Costantino 2012; Hammer 2012). More generally, biases and prejudices may be an impediment to valid research.

Other barriers to research on these agents are both perceived and real. Some concern the fear of legal prosecution even in jurisdictions where medicinal or recreational use has been legalized. Others involve skepticism about the efficacy of agents that are defined as having “no currently accepted medical use in treatment” and create suspicion among Institutional Review Board (IRB) members (Abrams 1998). Researchers, institutions, IRBs, funding and regulatory agencies may also be concerned about their reputations. Such worries can deter people from undertaking studies on the effectiveness of these agents. Fear of running afoul of the law or harming one's standing may also have an effect on the evaluation of studies that involve controlled drugs. These attitudes may affect funding agencies’ decisions about projects; indeed, NIDA, the NIH institute tasked with funding research on drug addiction is focused on investigating drug related harms and reduction, but not therapeutic benefits of of Schedule I drugs, in the words of its the director Nora Volkow: It is “not NIDA's mission to study the medicinal use of marijuana...” (Winter 2006)2

Selection of participants for these trials will present unique ethical challenges for those who evaluate study proposals. HIV+ populations include current and former users of controlled substances as well as people who have never or rarely used controlled drugs. Consideration of these groups of potential study participants will complicate the evaluation of standard research ethics questions. For example, are current, past, or non-users capable of providing informed consent for a study that involves their using a controlled drug? Is one group more vulnerable to addiction, abuse or relapse and in need of special protections than the others? Can a “Certificates of Confidentiality” issued by the NIH adequately protect the confidentiality of participants’ potentially incriminating substance use? (Check DK, Wolf LE, Dame LA, Beskow LM. Certificates of confidentiality and informed consent: perspectives of IRB chairs and institutional legal counsel.

IRB. 2014 Jan-Feb;36(1):1-8. PubMed PMID: 24649737; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4076050) Does drug experience convey more or less capacity to assess the risks and benefits involved in a study that involves controlled drug? Are the risks to current, past, or non-users more or less reasonable? Would the invitation to enroll in a study that provides controlled drugs constitute an “undue inducement”? Views on these questions may differ significantly between the various stakeholders in the research process (Bell 2011; Anderson 2012; Klitzman 2013) and they may vary significantly based on the hearsay reputation associated with a particular drug (Grinspoon 1995). Reviewers will need evidence-based guidance on how to respond to such questions when studies with controlled substances are proposed (Anderson 2007). To date, the ethical factors involved in research using controlled drugs have not been well-described, recommendations have not been well-developed, and there is almost no evidence-based guidance on how to assess these factors and proceed.

Little has been published on attitudes that may constitute barriers to research on controlled drugs (Anderson 2007). A few studies have surveyed physician attitudes towards prescribing Schedule I drugs. A 1984 paper reported variable and diverging attitudes towards heroin among researchers, clinicians and authorities, while advocating for research on the drug's pharmacological and clinical properties (Hamerle 2014). A 1994 paper that explored attitudes on long-term opioid prescription for chronic pain found concern about tolerance, dependence, and addiction varied significantly depending on specialty, prescribing habits, region, and regulatory pressure (Kahneman 2000). Gossop et al. surveyed practitioners in the U.K., (where heroin is on the national formulary) to elicit their concerns about prescribing heroin (Gossop 2005). He reported that the majority had no reservations about either prescribing or addiction. A 2011 Canadian focus group study explored the views of women who use illegal drugs on decisional capacity, stigma, and undue inducement in the context of research. That study found that the views of the surveyed women differed from prevailing attitudes in IRBs (Bell 2011). This minimal amount of evidence suggests that physicians’, patients’ and regulatory bodies’ attitudes towards controlled drugs are homogenous, while the dearth of studies on the therapeutic use of controlled drugs suggests that there are barriers: Cohen reviewed the Controlled Substances Act and FDA regulations related to research on medicinal uses of marijuana and proposed that “the ability of scientists to conduct impartial studies ...{has been} greatly hampered by political considerations” (Cohen 2006a; Cohen 2006b; Cohen 2010). The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies exposed barriers to research on Schedule I drugs in the U.S. (MAPS 2006). Their memorandum maintains that the process for conducting research into the medical uses of marijuana is obstructed by federal agencies blocking the supply of marijuana for clinical research and by guidelines and requirements created by the Department of Health and Human Services that apply solely to marijuana research. Abrams reported on multiple barriers to research and the difficulties he had in procuring marijuana for a study of treatment for HIV neuropathy (Abrams 1998).

Ethical concerns

Policy makers need to consider all of the harms and benefits that are likely to result from any regulation that limits access to and research on specific drugs. Among those harms and benefits, they need to reflect on whether and how the policy in question would limit liberty or disproportionally burden some individuals and thereby raise concerns about justice. Although the imposition of limitations on liberty and other societal burdens may be reasonable given the other benefits that they provide, policies with such effects – such as those bearing on research with controlled drugs -- require justification and, when possible, should be informed by empirical data. For example, are the restrictions on individual and institutional liberty posed by restrictive drug policies justified by their benefits? Do such policies impose burdens on some populations more than others, thereby creating justice concerns?

Liberty

Considerations of liberty are involved in the political questions of when and why some infringements on personal freedom are justified; we allow physicians broad freedom to administer drugs without recognized benefit, provided they obtained their patients’ informed consent. We allow the patient the freedom to refuse even lifesaving interventions, as long as they have decisional capacity. Significantly, researchers typically have the liberty to question established truth, some indeed consider this their calling. In contrast, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other federal laws and agencies limits these liberties as well as manufacturers’ liberties in marketing drugs and requires that substances be shown to be both safe and effective before they may be marketed and prescribed. FDA regulations are among federal regulations aiming at protecting and promoting health, promoting and maintaining well-being, and assuring that the public is protected from pharmaceutical products that are unsafe or ineffective, but by necessity do so at the expense of limiting research and commercial liberties. At the same time, these valuable regulations limit the array of substances that may be used freely by individuals for medicinal use and thereby limit liberty.

Justice

The formal principle of justice requires treating like cases alike and different cases differently. This principle would be easy to satisfy if it were possible to tell which factors were ethically salient for determining that cases were alike and which differences were irrelevant and could be ignored. In drug research, questions of social justice can be subtle and difficult to sort out. Whereas some conditions may be alleviated by a Schedule II or III substances (e.g. morphine) other conditions may only respond to a substances currently under Schedule I (e.g. marijuana). Is it just to allow research on a substance that may alleviate the pain of some patients and limit or prohibit research on a different substance that may alleviate the pain of other patients? When may research on a substance be limited, and why? Who will be affected by a limitation and will their share of burdens be fair?

Concerns of liberty and justice apply across morality. A number of additional issues specific to research ethics have, however, become key points for consideration in the review of protocols by funding agencies and IRBs. Several of these issues are likely to be especially complicated and controversial in the context of studies of controlled drugs on patients who are HIV+.

Risks

Out of concern for protecting research subjects from unreasonable risk, studies are required to minimize risks and IRBs are charged with balancing the study risks and potential benefits so as to determine whether they are reasonable. The risk/benefit assessment in studies of controlled drugs on people who are HIV+ will be especially difficult and complex. It is not clear when the risks of addiction and other harms associated with drug use are worth the potential benefit of alleviating burdensome symptoms. Furthermore, exaggerated risks (informed by media and urban legends) may distort judgment of actual risks. It is also not obvious whether the risks for a drug user are greater or less than the risks to a former drug user or a non-user. Legal risks also have to be added to the physical, psychological, social, and privacy concerns that are to be taken into account in the risk/benefit assessments. Decisions about the acceptability of a study should be informed by an accurate picture of potential legal consequences related to study participation as well as the legal exposure of investigators and institutions.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is a critically important condition for the ethical conduct of research (Kavalali 2012). Yet, it is not apparent whether patients who are currently or formerly using drugs are capable of providing informed consent. Patients are deemed to lose capacity to consent to a change in their surgical procedure after mild sedation in the operating room. At the same time, heavily medicated women with labor pain are considered capable of consenting to both research and interventions, as are patients who chronically use anxiolytic and pain medication.

Thus it is not clear whether the potential subjects in studies on therapeutic uses of controlled substances are capable of giving informed consent if they are using controlled substances. Are those who use drugs more like these who we consider intoxicated or like those with an underlying mental condition that does not impair their decisional capacity. Would people with a history of drug use be more or less informed because of their personal experience with controlled drugs?3

Undue inducements

In her 1981 paper, Ruth Macklin argued that offers of great benefits could overwhelm people's decisional capacity and compromise their judgment of risks and benefits to such an extent as to render them incapable of providing informed consent (Macklin 1981). Macklin declared that such inducements are “undue” and should be prohibited. That position has been vigorously debated in subsequent literature (Savulescu 2001; Largent 2013; Klitzman 2013a) and at least one study provides evidence that inducements do not impede judgment (Halpern 2004). In the context of research on controlled drugs, we anticipate that the issue of undue inducement will be raised. Reviewers are likely to ponder whether the offer of drugs to drug users would constitute an undue inducement. Similar questions about the undue inducement of providing drugs to drug users in research were directly addressed in a case discussed by Louis Charland in a 2002 paper, “Cynthia's Dilemma: Consenting to Heroin Prescription” (Charland 2002). Most, but not all (Rhodes 2002), of the numerous commentaries published along with the paper agreed with Charland that the inducement of providing clean needles and free heroin in that case was “undue” and that subjects could not provide consent.

To make appropriate ethical decisions about policy for conducting research with Schedule I substances, IRB members, researchers, potential participants, and funding agencies need a clear picture of how these issues are involved. Yet, separating bias from fact is difficult. Research policy decisions are further complicated by thinking about the three groups of potential participants in a Schedule I substance study. For example, are people who have had personal experience using drugs better informed than others or are they incapable of making a decision involving drug use because their desire for the drug is irresistible? For someone who has never been a drug user, are the risks associated with participating in a trial of a controlled drug greater or less than they would be for a current user or a former user?4 And is someone who has no personal experience with drug use and who does not personally know people who use drugs informed enough to make these judgments? Should cash incentives for participation in clinical trials be different for current, former and drug-naïve users? Evidence on whether and how bias affects judgments about these matters will be critical for the development of rational fact-based policies to guide research on controlled drugs.

Moving forward...

Literature on how ethically to conduct studies of Schedule I substances is surprisingly sparse. (Abrams 1998; Anderson 2007; Cohen 2009a; Cohen 2010; Hamerle 2014) The marginal level of attention indicates that research is needed to provide an accurate basis for research substances is required. In addition, because we have identified only a single study that compares different stakeholder views on issues in research ethics (Cohen 2009b), more in depth and systematic investigation is in order. Systematic and comprehensive studies would reveal whether and how the views of disparate groups differ: IRB members, researchers, clinicians, and people who are living with the conditions and symptoms that require attention. Each group has its own expertise and perspective. Areas of difference as well as areas of consensus are likely to be instructive. The empirical data combined with an overview of the legal status quo would provide a sound basis for recommending policy changes that would facilitate research on controlled drugs. It is instructive to examine the issues discussed above in light recent work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (Elliott 1999), DT Gilbert (Castells 2010; Charland 2002), and TD Wilson (Kempner 2005). In their widely accepted work on normal human psychology, these psychologists have established a cognitive basis for common human errors and explained how frequently human judgment is infected with bias. We have only identified five papers that apply their robust findings to bioethics (Cohen 2009a; DEA 2007; Hatzenbuehler 2013; Hawkins 2005; Hoffmann 2010). None of these articles address issues in research ethics. Yet, it may be especially important to be aware of distortions in judgment that reflect cognitive basis when formulating policy recommendations for research with Schedule I substances. If empirical studies identify contradictory stakeholder judgments, the views of at least one group may reflect bias. Inconsistent views could be compared to the scientific literature to discern which views have a basis in fact and which are likely to reflect a cognitive distortion. Such an innovative approach to resolving controversies in bioethics would be useful in guiding policy recommendations.

Specifically, studies designed for guiding policy on research with Schedule I drugs should focus on answering the following questions:

-

(1)

Is there agreement or are there differences in the views of stakeholder groups on the potential subjects’ decisional capacity, ability to assess risks and benefits, vulnerability, and susceptibility to inducement?

-

(2)

Is there agreement or are there differences in judgments regarding the acceptable degree of risk exposure for the three groups of possible subjects, namely, current drug users, former drug users, and non-users?

-

(3)

Is there agreement or are there differences in judgments regarding the degree of risks and the overall acceptability of specific studies with respect to drugs that have different social connotations and drugs that differ in their addictive potential or health risks?

Study findings of a clear consensus on an issue of research ethics could offer a starting point for policy development. Scientific evidence that supports one of two opposing views will provide evidence to support data-based recommendations. When the views of different groups differ, there may not be empirical data to support one position or the other. In some cases the alignment of views (e.g., patients versus professionals, or people with direct experience versus those lacking direct experience) may be enlightening. In other cases after identifying the disparity in views, the only reasonable solution may be to call for more scientific investigation. The key caveat for policy makers will be to remain mindful of these possibilities and careful to avoid drawing conclusions that the data does not support.

Conclusions

Social views about marijuana have been changing rapidly, its legal status is in flux, and views about its safety and efficacy will continue to evolve. The issues that we have identified are certainly relevant to the need for research on the efficacy and safety of marijuana. Our point, however, is broader. It is likely that several drugs currently classified under Schedule I have important therapeutic potential for the relief of symptoms as well as for the management of the underlying chronic conditions. Without research, that potential cannot be detected or verified and the potential benefits cannot be dispersed. The Catch 22 of the status quo is that the classification of drugs as Schedule I amounts to an unsurmountable barrier to research.

As matters of liberty and justice, changes are needed in FDA and DEA policies so as to make research on substances currently classified as Schedule I more feasible and less restricted. At the same time, because the research will involve concerns about the ethical conduct of research, the specific issues related to such research need to be carefully identified and considered. And because views about issues related to drugs, drug users, and addiction are likely to be infected with bias, and because conflicts of interest are likely to affect the judgment of IRB members as well as clinicians and researchers, policy makers need to hold fast to requiring evidence for guiding their recommendations and avoid pronouncements that are not supported by data.

Policy makers should seek and employ study findings as the basis deciding how existing regulations should be revised and in offering their recommendations. Their clear goal must be to allow research to proceed on regulated drugs in accordance with the highest ethical standards and without being swayed by political agendas, preconceptions, or prejudices. IRBs that are responsible for reviewing studies of Schedule I drugs, investigators who are interested in conducting studies, and funding institutes and agencies that sponsor such research should also be aware of the need for an evidentiary basis for grounding their decisions.

Table 2.

Barriers to investigator initiated drug research and development

| Process | Barrier |

|---|---|

| Pilot study to test a hypothesis about a new therapeutic application of a controlled substance and collect preliminary data for subsequent grant application and clinical trial | • Difficulty overcoming the scrutiny of the institutional review board in light of real and perceived concerns related to studying illegal substances • Difficulty in legally procuring the study drug • Concern about stigmatization of investigator among their peers and within the institution • Concern about the social risks to study volunteers |

| Obtaining a federal research grant to scale up research efforts and cover clinical trial expenses | • Conflict with federal and state legislation, • Investigating the therapeutic benefits of controlled substances is “not within NIDA's mission” • Even applications that are ranked highly ranked by NIH peer reviewers may not be funded |

| Conducting a large scale randomized clinical trial to provide evidence in support a hypothesis about a new therapeutic application of a controlled substance, and thereby demonstrate its safety and medical benefit | • Academic leadership may be concerned about institutional reputation • Community may concern about effects on local crime • News media may scrutinize research on “gateway drugs” |

Legal, regulatory, ethical and social barriers obstruct the progress at every step in the typical process of investigator initiated research on the therapeutic benefits of controversial controlled substances; for example, NIDA, the NIH institute concerned with controlled substances research, will not fund applications investigating therapeutic benefits because it is “not within their mission”.

Acknowledgements

Drs. Sacks, Andreae and Indyk were supported in part by grant no. 1R01AT005824-01 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. MHA was supported in part by the CTSA Grant 1 UL1 TR001073-01, UL1TR000067, 1 TL1 TR001072-01, 1 KL2 TR001071-01 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work must adhere to the Public Access Policy. We would also like to acknowledge Maud Dupuy for her support in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

We limit ourselves in this manuscript to medical indications of controversial controlled substances and do not address issues regarding their recreational use.

We experienced this first hand when our R01 NIH grant application was highly scored as exceptional to outstanding and better than 96% of all other applications in response to the PAR-12-244 on Ethical Issue s in Research o n HIV /AIDS and its Co-morbidities, but was not funded because investigating barriers to research on therapeutic benefits of controlled substances “doesn't fit their priorities”.

Vulnerability is a separate contentious issue, which we are not addressing in this paper.

Could a comparison with analogous issues regarding inclusion research subjects with a history of ethanol use be helpful? We doubt this as the therapeutic potential of alcohol is limited to the treatment of acute methanol intoxication and disinfection.

References

- Publications.parliament.uk [January 22 2015];'House Of Commons - Science And Technology - Written Evidence'. 2015 http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cm.

- Abrams DI, Jay CA, Shade SB, Vizoso H, Reda H, Press S, Kelly ME, Rowbotham MC, Petersen KL. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68(7):515–-521. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams DI. Medical marijuana: tribulations and trials. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30(2):163–-169. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal Sunil K., Carter Gregory T., Sullivan Mark D., ZumBrunnen Craig, Morrill Richard, Mayer Jonathan D. Medicinal use of cannabis in the United States: historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5(3):153–-168. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Michelle. The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alper KR, Lotsof HS, Frenken GM, Luciano DJ, Bastiaans J. Treatment of acute opioid withdrawal with ibogaine. Am J Addict. 1999;8(3):234–-242. doi: 10.1080/105504999305848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Emily E, DuBois James M. IRB Decision-Making with Imperfect Knowledge: A Framework for Evidence-Based Research Ethics Review. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(4):951–-969. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Emily E, DuBois James M. The need for evidence-based research ethics: A review of the substance abuse literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86(2):95–-105. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Emily E., Solomon Stephanie, Heitman Elizabeth, DuBois James M., Fisher Celia B., Kost Rhonda G., Lawless Mary Ellen, Ramsey Cornelia, Jones Bonnie, Ammerman Alice, Ross Lainie Friedman. Research ethics education for community-engaged research: a review and research agenda. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012 Apr;7(2):3–-19. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae Michael, Debbie Indyk George Carter, Matthew Johnson Katherine Suslov, Sacks Henry. American Public Health Association 140Th Annual Meeting. American Public Health Association; 2012. 'Lack Of Guidelines For Use Of Medical Marijuana For HIV Neuropathic Pain'. https://apha.confex.com/apha/140am/webprogram/Paper265212.html. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio Tamara, Childers Steven R, Rothman Richard B, Dersch Christina M, King Christine, Kuehne Martin, Bornmann William G, Eshleman Amy J, Janowsky Aaron, Simon Eric R, Reith Maarten E A., Alper Kenneth. Effect of Iboga alkaloids on $$-opioid receptor-coupled G protein activation. PLoS One. 8(10)(2013):e77262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Kirsten, Salmon Amy. What women who use drugs have to say about ethical research: findings of an exploratory qualitative study. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011 Dec;6(4):84–-98. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.4.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Berridge Virginia. Heroin prescription and history. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug;361(8):820–-821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0904243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J. Weed control. The Boston Globe; May 28, 2006. Retrieved from http://www.boston.com. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone Samuel. Portugal Decriminalized All Drugs Eleven Years Ago And The Results Are Staggering. Business Insider International; 2012. [April 20 2015]. http://www.businessinsider.com/portugal-drug-policy-decriminalization-works-2012-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick J Michael. Blurred boundaries: the therapeutics and politics of medical marijuana. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Feb;87(2):172–-186. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff Joan L., Bissell Laura J L., Balneaves Lynda G, Oliffe John L, Capler N Rielle, Buxton Jane. Perceptions of cannabis as a stigmatized medicine: a qualitative descriptive study. Harm Reduct J. 10(2013):2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulling Simon, Schicker Klaus, Zhang Yuan-Wei, Steinkellner Thomas, Stockner Thomas, Gruber Christian W., Boehm Stefan, Freissmuth Michael, Rudnick Gary, Sitte Harald H., Sandtner Walter. The mechanistic basis for noncompetitive ibogaine inhibition of serotonin and dopamine transporters. J Biol Chem. 2012 May;287(22):18524–-18534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.343681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter Adrian, Hall Wayne. The issue of consent in research that administers drugs of addiction to addicted persons. Account Res. 2008;15(4):209–-225. doi: 10.1080/08989620802388689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells Xavier, Casas Miguel, Pérez-Macá Clara, Roncero Carlos, Vidal Xavier, Capella Dolors. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):CD007380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007380.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charland Louis C. Cynthia's dilemma: consenting to heroin prescription. Am J Bioeth. 2002;2(2):37–-47. doi: 10.1162/152651602317533686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Peter J. Medical marijuana 2010: it's time to fix the regulatory vacuum. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38(3):654–-666. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Peter J. Medical marijuana: the conflict between scientific evidence and political ideology. Part two of two. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23(2):120–-140. doi: 10.1080/15360280902900620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Peter J. Medical marijuana: the conflict between scientific evidence and political ideology. Part one of two. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23(1):4–-25. doi: 10.1080/15360280902727973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino Cristina Maria, Gupta Achla, Yewdall Alice W., Dale Benjamin M., Devi Lakshmi A., Chen Benjamin K. Cannabinoid receptor 2-mediated attenuation of CXCR4-tropic HIV infection in primary CD4+ T cells. PLoS One. 7(3)(2012):e33961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEA . Schedules of Controlled Substances. Office of Diversion Control, Drug Enforcement Administration; 2007. United States Code (USC) Controlled Substances Act: Section 812. GPO Access [ www.gpoaccess.gov] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt Louisa, Hall Wayne. The Health and Psychological Effects of ecstasy (MDMA) Use. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales Sydney; Australia: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diep Francie. Clearing the Smoke. Scientific American 305. 2011;4:21–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly Jennifer R. The need for ibogaine in drug and alcohol addiction treatment. J Leg Med. 2011 Jan;32(1):93–-114. doi: 10.1080/01947648.2011.550832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine Mitch. Understanding marijuana: A new look at the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elia Nadia, Tramèr Martin R. Ketamine and postoperative pain–a quantitative systematic review of randomised trials. Pain. 2005 Jan;113(1-2):61–-70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Fischer CT, Rennie DL. Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J Clin Psychol. 1999 Sep;38(Pt 3):215–-229. doi: 10.1348/014466599162782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Ronald J., Toperoff Will, Vaida Florin, van den Brande Geoffrey, Gonzales James, Gouaux Ben, Bentley Heather, Atkinson J Hampton. Smoked medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 Feb;34(3):672–-680. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup Nanna Brix, Sindrup Swren Hein, Jensen Troels Staehelin. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010 Sep;150(3):573–-581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JA, Byck R, Barash PG. Pharmacology and therapeutic applications of cocaine. Anesthesiology. 1990 Sep;73(3):518–-531. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199009000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh Sabyasachi, Chandran Arthi, Jansen Jeroen P. Epidemiology of HIV-related neuropathy: a systematic literature review. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012 Jan;28(1):36–-48. doi: 10.1089/AID.2011.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles Michelle, Workman Cassy. Clinical manifestations and the natural history of HIV. HIV Management in Australasia. 2009:125–-131. [Google Scholar]

- Gossop Michael, Keaney Francis, Sharma Pankaj, Jackson Mark. The unique role of diamorphine in British medical practice: a survey of general practitioners and hospital doctors. Eur Addict Res. 2005;11(2):76–-82. doi: 10.1159/000083036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer G, Tolbert R. Subjective reports of the effects of MDMA in a clinical setting. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1986;18(4):319–-327. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1986.10472364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB, Doblin R. Marijuana, the AIDS wasting syndrome, and the U.S. government. N Engl J Med. 1995 Sep;333(10):670–-671. doi: 10.1056/nejm199509073331020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern Scott D., Karlawish Jason H T., Casarett David, Berlin Jesse A, Asch David A. Empirical assessment of whether moderate payments are undue or unjust inducements for participation in clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Apr;164(7):801–-803. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamerle M, Ghaeni L, Kowski A, Weissinger F, Holtkamp M. Cannabis and other illicit drug use in epilepsy patients. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(1):167–-170. doi: 10.1111/ene.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Rachel R., Dingel Molly J., Ostergren Jenny E., Nowakowski Katherine E., Koenig Barbara A. The experience of addiction as told by the addicted: incorporating biological understandings into self-story. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;36(4):712–-734. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington RD, Woodward JA, Hooton TM, Horn JR. Life-threatening interactions between HIV-1 protease inhibitors and the illicit drugs MDMA and gamma-hydroxybutyrate. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Oct;159(18):2221–-2224. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L., Link Bruce G. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc Sci Med. 2014 Feb;103:1–-6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins Jennifer S., Emanuel Ezekiel J. Clarifying confusions about coercion. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005;35(5):16–-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic Use of Heroin: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-sixth Congress, Second Session, on HR 7334... September 4, 1980. US Government Printing Office; 1980. Foreign Commerce. Subcommittee on Health. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann Diane E., Weber Ellen. Medical marijuana and the law. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr;362(16):1453–-1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson Roni. Mystical Medicine. Scientific American Mind. 2014;25(5):24–-24. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Tversky Amos. Choices, values, and frames. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kavalali Ege T., Monteggia Lisa M. Synaptic mechanisms underlying rapid antidepressant action of ketamine. Am J Psychiatry. 2012 Nov;169(11):1150–-1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempner Joanna, Perlis Clifford S., Merz Jon F. Ethics. Forbidden knowledge. Science. 2005 Feb;307(5711):854. doi: 10.1126/science.1107576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall JM, Reeves BC, Latter VS, Nasal Diamorphine Trial Group Multicentre randomised controlled trial of nasal diamorphine for analgesia in children and teenagers with clinical fractures. BMJ. 2001 Feb;322(7281):261–-265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer Beau, Caulkins Jonathan P., Bond Brittany M., Reuter Peter H. Reducing Drug Trafficking Revenues and Violence in Mexico: Would Legalizing Marijuana in California Help? RAND Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 2010. http://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP325. Also available in print form. [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman Robert. How IRBs view and make decisions about coercion and undue influence. J Med Ethics. 2013 Apr;39(4):224–-229. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman Robert. From “Male Bonding Rituals” to “Suicide Tuesday”: A qualitative study of issues faced by gay male ecstasy (MDMA) users. J Homosex. 2006;51(3):7–-32. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Xaver, Kovar Michael, Boehm Stefan, Sandtner Walter, Hilber Karlheinz. Anti-addiction drug ibogaine inhibits hERG channels: a cardiac arrhythmia risk. Addict Biol. 2014 Mar;19(2):237–-239. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppel Barbara S., Brust John C M., Fife Terry, Bronstein Jeff, Youssof Sarah, Gronseth Gary, Gloss David. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014 Apr;82(17):1556–-1563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousik Sharanya M., Napier T Celeste, Carvey Paul M. The effects of psychostimulant drugs on blood brain barrier function and neuroinflammation. Front Pharmacol. 3(2012):121. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer Joan L. Medical marijuana for cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014 Dec; doi: 10.3322/caac.21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largent Emily, Grady Christine, Miller Franklin G., Wertheimer Alan. Misconceptions about coercion and undue influence: reflections on the views of IRB members. Bioethics. 2013 Nov;27(9):500–-507. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2012.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Jih-Heng, Vicknasingam Balasingam, Cheung Yuet-Wah, Zhou Wang, Nurhidayat Adhi, Wibowo Jarlais, Des Don C, Schottenfeld Richard. To use or not to use: an update on licit and illicit ketamine use. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2011;2:11–-20. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutge Elizabeth E., Gray Andy, Siegfried Nandi. The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD005175. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005175.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin Ruth. On paying money to research subjects: 'due' and 'undue' inducements. IRB. 1981 May;3(5):1–-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchette Robert B, Danis Jan Shelton. Guide to federal records in the National Archives of the United States. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- May Edgar. Dealing with Drug Abuse: A report to the Ford Foundation. Praeger; New York Washington: 1972. Narcotics addiction and control in Great Britain. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister William B. The global political economy of scheduling: the international–historical context of the Controlled Substances Act. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004 Oct;76(1):3–-8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes Rhona J., Hillan Edith, Clark Diana, Gilmour Harper. Diamorphine for pain relief in labour : a randomised controlled trial comparing intramuscular injection and patient-controlled analgesia. BJOG. 2004 Oct;111(10):1081–-1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondzac AM. In defense of the reintroduction of heroin into American medical practice and H.R. 5290–the Compassionate Pain Relief Act. N Engl J Med. 1984 Aug;311(8):532–-535. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408233110812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musto David F. The marihuana tax act of 1937. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26(2):101–-108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750200005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahas GG, Greenwood A. The first report of the National Commission on marihuana (1972): signal of misunderstanding or exercise in ambiguity. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1974 Jan;50(1):55–-75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuijten Mascha, Blanken Peter, van den Brink Wim, Hendriks Vincent. Treatment of crack-cocaine dependence with topiramate: A randomized controlled feasibility trial in The Netherlands. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014 May;138(0):177–-184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Joekes Eugenia, Brissette Suzanne, Marsh David C., Lauzon Pierre, Guh Daphne, Anis Aslam, Schechter Martin T. Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug;361(8):777–-786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. The psychotherapeutic potential of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine): an evidence-based review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007 Apr;191(2):181–-193. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes Rosamond. Unsafe presumptions in clinical research. Am J Bioeth. 2002;2(2):49–-51. doi: 10.1162/152651602317533703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roback Mark G., Wathen Joe E., MacKenzie Todd, Bajaj Lalit. A randomized, controlled trial of i.v. versus i.m. ketamine for sedation of pediatric patients receiving emergency department orthopedic procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 2006 Nov;48(5):605–-612. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson Kevin, Bayon Carmen, Molina Jean-Michel, McNamara Patricia, Resch Christiane, Mucoz-Moreno Jose A., Kulasegaram Ranjababu, Schewe Knud, Burgos-Ramirez Angel, De Alvaro Cristina, Cabrero Esther, Guion Matthew, Norton Michael, van Wyk Jean. Screening for neurocognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety in HIV-infected patients in Western Europe and Canada. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1555–-1561. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.936813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savulescu Julian. The fiction of” undue inducement”: Why researchers should be allowed to pay participants any amount of money for any reasonable research project. American Journal of Bioethics. 2001;1(2):1g–-3g. [Google Scholar]

- Sawynok Jana. Topical and peripheral ketamine as an analgesic. Anesth Analg. 2014 Jul;119(1):170–-178. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa Ben. Is there a case for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in the UK?. J 36 Psychopharmacol. 2007 Mar;21(2):220–-224. doi: 10.1177/0269881107069029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Edinete M., Cirne-Santos Claudio C., Frugulhetti Izabel C., Galvão-Castro Bernardo, Saraiva Elvira M., Kuehne Martin E, Bou-Habib Dumith Chequer. Anti-HIV-1 activity of the Iboga alkaloid congener 18-methoxycoronaridine. Planta Med. 2004 Sep;70(9):808–-812. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz James. Substance Abuse in America: A Documentary and Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group; Westport, CT: 2012. p. 259. [Google Scholar]

- Volkow Nora D., Baler Ruben D., Compton Wilson M., Weiss Susan R B. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun;370(23):2219–-2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware Mark A., Wang Tongtong, Shapiro Stan, Robinson Ann, Ducruet Thierry, Huynh Thao, Gamsa Ann, Bennett Gary J., Collet Jean-Paul. Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2010 Oct;182(14):E694–-E701. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee Michael Y K., Tuckey Jenny P., Thomas Peter, Burnard Sara. The IDvIP trial: a two-centre randomised double-blind controlled trial comparing intramuscular diamorphine and intramuscular pethidine for labour analgesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 11(2011):51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee MYK, Tuckey JP, Thomas PW, Burnard S. A comparison of intramuscular diamorphine and intramuscular pethidine for labour analgesia: a twocentre randomised blinded controlled trial. BJOG. 2014 Mar;121(4):447–-456. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsey Barth, Marcotte Thomas, Deutsch Reena, Gouaux Ben, Sakai Staci, Donaghe Haylee. Low-dose vaporized cannabis significantly improves neuropathic pain. J Pain. 2013 Feb;14(2):136–-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau Gary L., Jackman Christopher S., Hooper Philip L., Sheidow Tom G. Intravitreal injection anesthesia–comparison of different topical agents: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Feb;151(2):333–-7. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinberg Norman E, Robertson John A. Drugs and the Public.: Simon and Schuster New York, 1972. “HIV in the USA–pushing past the plateau.”. Lancet. 2013 Jul;382(9889):285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]