Summary

Cholesterol deficiency, a new autosomal recessive inherited genetic defect in Holstein cattle, has been recently reported to have an influence on the rearing success of calves. The affected animals show unresponsive diarrhea accompanied by hypocholesterolemia and usually die within the first weeks or months of life. Here, we show that whole genome sequencing combined with the knowledge about the pedigree and inbreeding status of a livestock population facilitates the identification of the causative mutation. We resequenced the entire genomes of an affected calf and a healthy partially inbred male carrying one copy of the critical 2.24‐Mb chromosome 11 segment in its ancestral state and one copy of the same segment with the cholesterol deficiency mutation. We detected a single structural variant, homozygous in the affected case and heterozygous in the non‐affected carrier male. The genetic makeup of this key animal provides extremely strong support for the causality of this mutation. The mutation represents a 1.3kb insertion of a transposable LTR element (ERV2‐1) in the coding sequence of the APOB gene, which leads to truncated transcripts and aberrant splicing. This finding was further supported by RNA sequencing of the liver transcriptome of an affected calf. The encoded apolipoprotein B is an essential apolipoprotein on chylomicrons and low‐density lipoproteins, and therefore, the mutation represents a loss of function mutation similar to autosomal recessive inherited familial hypobetalipoproteinemia‐1 (FHBL1) in humans. Our findings provide a direct gene test to improve selection against this deleterious mutation in Holstein cattle.

Keywords: diarrhea, disruptive mutation, gene test, hypobetalipoproteinemia, hypocholesterolemia, lipid malabsorption, rearing success, RNAseq, whole genome sequencing

Recently, a new recessive genetic defect was discovered in Holstein cattle that causes young calves to die within a period of days to months after birth as a consequence of the onset of idiopathic diarrhea (Kipp et al. 2015). Affected animals show hypocholesterolemia. The family history of the affected calves suggested an autosomal monogenic recessive inherited fat metabolism disorder, which was named cholesterol deficiency (CD; OMIA 001965‐9913). A combined approach of a genome‐wide association study (GWAS) and homozygosity mapping revealed a ~2.7‐Mb disease‐associated haplotype on BTA 11 (Kipp et al. 2015). The disease‐associated haplotype traces to the Holstein sire Maughlin Storm born in 1991 (VanRaden & Null 2015). Maughlin Storm's sire and maternal grandsire are genotyped and do not carry this disease‐associated haplotype. Maughlin Storm's great grandsire along the maternal lineage, Fairlea Royal Mark, born in 1966, has not been genotyped but is the sire of Willowholme Mark Anthony, born in 1975, the origin of the ancestral version of the haplotype (Fig. 1a). It was assumed that Willowholme Mark Anthony must carry the ancestral normal haplotype, from which the mutant haplotype arose, because several artificial insemination sires received a copy of this haplotype through their maternal lines, and homozygous calves descending from these bulls live normal lives (Kipp et al. 2015; VanRaden & Null 2015). In conclusion, it was speculated that the mutation causing CD must have occurred in the three generations between Fairlea Royal Mark and Maughlin Storm, or even earlier, if this sire was homozygous for the BTA 11 haplotype. As the currently applied indirect haplotype‐based test is not able to determine CD carriers without considering pedigree information, the aim of this study was to identify the causal mutation.

Figure 1.

Genetics of cholesterol deficiency (CD) in Holstein cattle. (a) Pedigree of selected partially inbred Holstein cattle. The two BTA 11 haplotypes are indicated beneath each animal's name. Black symbols represent the ancestral haplotype; those labeled CD indicate the mutant ancestral haplotype. The bull Maughlin Storm (red arrow) is the possible founder animal for CD. Thus, the mutation (indicated by CD) must have occurred either in the germlines of Fairlea Royal Mark, Wykholme Dewdrop Gail or Wykholme Dewdrop Tacy or during the early embryonic development of Maughlin Storm. Gray symbols represent any other wild‐type haplotype of this region of BTA 11. Due to the inbreeding loop through ancestor Fairlea Royal Mark, the male Dudoc Mr Burns has inherited two versions of the ancestral haplotype. His maternal copy of the ancestral haplotype carries the CD mutation, whereas his paternal copy is still in its ancestral wild‐type state. (b) High‐density SNP marker‐based homozygosity mapping across the genome of two affected calves. Extended segments of shared homozygosity are shown in blue. Note should be taken that the largest homozygous segment is located on BTA 11. The observed recombination event (red arrow) in the non‐affected carrier male Dudoc Mr Burns allowed the determination of a 2.24‐Mb critical interval (indicated in red) containing the APOB gene.

Initially, two of 23 available CD‐affected animals were genotyped using the BovineHD BeadChip technology (Illumina). We assumed that these two affected animals were identical by descent (IBD) for the causative mutation and flanking chromosomal segments. Therefore, a search for extended regions of homozygosity with simultaneous allele sharing was performed as previously described (Murgiano et al. 2014), resulting in the discovery of 16 genome regions fulfilling these criteria (Fig. 1b). By far, the largest homozygous segment, over 3711 SNP markers, corresponds to a 12.1Mb interval from 76.8 to 88.9 on BTA 11. Based on pedigree and 50 k SNP marker data, a non‐affected male (Dudoc Mr Burns) was IBD for a significant part of the critical segment of BTA 11, except for the causative mutation, which we predicted to reside only on his maternally derived chromosome (Fig. 1a). This male showed a recombination event, which allowed us to narrow down the critical interval harboring the causative mutation to 2.24 Mb, from 76 826 569 to 79 072 589 bp, on BTA 11 (Fig. 1b). Observing an almost matching overlap of the previously reported GWAS hit and the IBD region on BTA 11, we concluded that this single genome interval was highly likely to contain the causative mutation for CD.

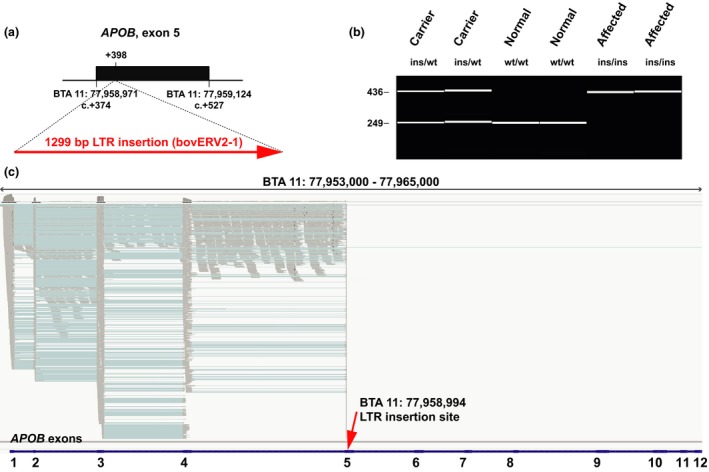

In addition to one affected calf, we chose the identified non‐affected carrier male Dudoc Mr Burns for complete resequencing of the entire genome, as the detection of a heterozygous variant in the critical BTA 11 region in this animal should reveal the causative mutation (Fig. 1a). We prepared PCR‐free fragment libraries with 400‐bp insert sizes from both animals, which were sequenced to 19.2× (affected calf) and 16.4× (non‐affected carrier) coverage on a single lane of an Illumina HiSeq3000 instrument using 2× 150‐bp paired‐end reads. The genome sequencing data were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under accession no. PRJEB11963. The mapping to the UMD3.1 bovine reference genome assembly and variant calling were undertaken as previously described (Murgiano et al. 2014). Within the critical region of 2.24 Mb, a total of 3661 homozygous variants were identified in the affected calf. The comparison between the case and the non‐affected male revealed that all these variants were homozygous in the non‐affected male and could thus be excluded as causative variants. We then visually inspected the short read alignments in the critical interval using the integrated genomics viewer (igv; Thorvaldsdóttir et al. 2013) to search for structural variants that would have most likely been missed before. Several truncated read alignments in the region of exon 5 of the APOB gene indicated a potential duplication and/or insertion event (Fig. S1). We designed primers flanking exon 5 and amplified this region in a long‐range PCR (Fig. S2). Sanger sequencing of the product of the affected calf revealed a 1299bp transposable LTR element (ERV2‐1) insertion after genome position 77 958 994 on BTA 11, located between nucleotides 24 and 25 of APOB exon 5 (Fig. 2a). The nucleotide sequence of the mutant APOB allele with the LTR insertion was deposited in the dbVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbvar) under accession no. NSTD119, and the mutant allele can be described as APOB:c.398_399insNSTd119:g.1_1299 (Fig. S3). The APOB insertion was validated by a diagnostic PCR using three primers, and subsequent automated capillary electrophoresis (Fragment Analyzer; Advanced Analytical Technologies) confirmed that a total of 23 affected animals were homozygous, whereas four available obligate carriers (dams of affected calves) and the non‐affected carrier male Dudoc Mr Burns were all heterozygous (Fig. 2b). Thereby, we confirmed that non‐affected carriers were indeed heterozygous for this APOB variant, whereas the affected calves were homozygous mutant compared to the reference sequence. None of the 264 artificial insemination Holstein sires that were subsequently tested until the time of writing this manuscript had the homozygous mutant genotype, but 46 of them were heterozygous for the APOB insertion. The cohort of 264 males included Maughlin Storm, his sire Madawaska Aerostar, as well as his maternal grandsire Hanover Hill Inspiration. We experimentally confirmed the heterozygous APOB genotype for Maughlin Storm and showed in contrast that both male ancestors were homozygous wild type, confirming earlier assumptions (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, only 37 of the identified 46 carriers were classified before as cholesterol deficiency haplotype carriers using the indirect SNP marker‐based test described above. Thus, the allele frequency of the deleterious allele within this sample of Holstein cattle was higher than assumed before. Lastly, we screened a genetically diverse panel of 66 animals from 20 breeds with available whole genome sequence data to confirm that the identified mutation does not occur outside the Holstein population. Visual inspection revealed that none of the 132 chromosomes in this sample showed the causative insertion.

Figure 2.

Transposable element insertion in exon 5 of the APOB gene. (a) Schematic representation of the insertion. A 1299bp bovine LTR element (ERV2‐1) insertion was found in CD‐affected Holstein calves after position +398 of the APOB‐coding sequence. (b) Experimental genotyping of the insertion by fragment size analysis. A diagnostic PCR performed on genomic DNA using a combination of three allele‐specific primers allows for genotype differentiation. The capillary gel electrophoresis picture shows a dam heterozygous for the insertion (ins) and the wild‐type (wt) allele, the heterozygous carrier male Dudoc Mr Burns (ins/wt), two normal controls (wt/wt) and two affected calves (ins/ins). (c) igv screenshot of the mapped liver RNA‐seq sequence reads of a homozygous mutant affected calf (shown in gray). Spliced cDNA sequence reads (indicated by blue lines spanning the introns) correspond to APOB exons 1–5 and non‐spliced reads map to the introns 1–4. Note the absence of reads mapping to the 3′‐part of exon 5 after the insertion site (red arrow) and to exons 6–12 (up to 36, not shown). The annotation of exons 1–12 of the bovine APOB gene is shown by blue bars at the bottom.

Finally, we investigated the effect of the 1299‐bp insertion on the APOB transcript, as the full‐length insertion is predicted to result in a frameshift beginning with amino acid residue 135 in the bovine APOB protein sequence and to lead to a 97% truncation of the corresponding 4567 amino acid long protein (p.Gly135ValfsX10). We isolated liver RNA from an affected calf shown to be homozygous for the APOB insertion, produced a cDNA library and sequenced 2× 150 bp on a quarter of a lane on an Illumina HiSeq3000 instrument. The RNA sequencing data were deposited in the ENA under accession no. PRJEB11965. Transcriptome data were mapped to the UMD3.1 bovine reference genome assembly according to a previously established pipeline (Pacholewska et al. 2015). Mapped RNA sequence reads were visually evaluated using igv in the region of the annotated APOB gene, which spans ~87 kb (BTA 11: 77 953 380–78 040 118 bp) and encompasses 36 coding exons. Interestingly, numerous sequence reads were mapped exactly with correct splicing, according to the annotated exons 1–5 of the APOB gene, up to the position of the genomic insertion within exon 5 (Fig. 2c). However, there was also a significant fraction of reads mapping to the introns, especially in intron 4, indicating intron retention. Thus, nonsense‐mediated decay apparently is not a major consequence of the insertion. However, it is unclear whether mutant proteins are actually expressed, as with more than 97% of the normal APOB protein missing, it is very unlikely that possible mutant proteins fulfill any physiological function. The APOB gene encodes apolipoprotein B, representing the main apolipoprotein on chylomicrons and low‐density lipoproteins. Therefore, we assume that the mutation represents a high likelihood of a loss of function mutation similar to autosomal recessive inherited familial hypobetalipoproteinemia‐1 (FHBL1) in humans (OMIM 615558). Due to truncating APOB mutations, human FHBL1 is characterized by hypocholesterolemia and malabsorption of lipid‐soluble vitamins leading to retinal degeneration, neuropathy and coagulopathy (Young et al. 1988).

We believe that we have established the causality of the APOB mutation for CD in Holstein cattle based on the following arguments: (i) the perfect association of the APOB mutation with the CD phenotype; (ii) the non‐affected animal, which was IBD for all sequence variants across the critical interval, being also heterozygous for the APOB mutation; (iii) the shown consequences at the transcript level and the obvious functional impact of the insertion on the encoded protein and (iv) the phenotypic similarities to human APOB‐associated disorders.

In summary, we have successfully applied a next‐generation sequencing‐based strategy to identify APOB as the causative gene for cholesterol deficiency and, thereby, developed for the first time a direct gene test for Holstein cattle. This new tool will enhance the chances of eliminating this fatal genetic disease from the international Holstein cattle population.

Supporting information

Figure S1. igv screenshot of the region with the insertion.

Figure S2. Long‐range PCR confirmed the insertion.

Figure S3. Sequences of the bovine APOB alleles.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all cattle breeders and veterinarians for providing blood samples. The authors would like to thank the Swiss cattle breeding associations (www.swissherdbook.ch and www.holstein.ch) for supporting the sampling. We acknowledge the Next Generation Sequencing Platform of the University of Bern for performing the sequencing experiments and Sabrina Schenk for expert technical assistance.

References

- Kipp S., Segelke D., Schierenbeck S. et al (2015) A new Holstein haplotype affecting calf survival. Proceedings of the 2015 Interbull Meeting, July 09–12, 2015, Orlando, Florida, USA. Interbull Bulletin 49, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Murgiano L., Jagannathan V., Calderoni V., Joechler M., Gentile A. & Drögemüller C. (2014) Looking the cow in the eye: deletion in the NID1 gene is associated with recessive inherited cataract in Romagnola cattle. PLOS One 9, e110628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacholewska A., Drögemüller M., Klukowska‐Rötzler J., Lanz S., Hamza E., Dermitzakis E.T., Marti E., Gerber V., Leeb T. & Jagannathan V. (2015) The transcriptome of equine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLOS One 10, e0122011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsdóttir H., Robinson J.T. & Mesirov J.P. (2013) integrative genomics viewer (igv): high‐performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in Bioinformatics 14, 178–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRaden P. & Null D. (2015) Holstein haplotype for cholesterol deficiency (HCD). https://www.cdcb.us/reference/changes/HCD_inheritance.pdf

- Young S.G., Northey S.T. & McCarthy B.J. (1988) Low plasma cholesterol levels caused by a short deletion in the apolipoprotein B gene. Science 241, 591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. igv screenshot of the region with the insertion.

Figure S2. Long‐range PCR confirmed the insertion.

Figure S3. Sequences of the bovine APOB alleles.