Abstract

Background and aims

Resilience encompasses factors promoting effective functioning in the context of adversity. Data regarding resilience in the wake of accidental trauma is still scarce. The aim of the current study is to comparatively assess adaptive, life – promoting factors in persons exposed to motor vehicle accidents (MVA) vs. persons exposed to other types of accidents, and to identify psychological factors of resilience and vulnerability in this context of trauma exposure.

Methods

We assessed 93 participants exposed to accidents out of 305 eligible patients from the Clinical Rehabilitation Hospital and Cluj County Emergency Hospital. The study used Reasons for Living Inventory (RFL) and Life Events Checklist. Scores were comparatively assessed for RFL items, RFL scale and subscales in participants exposed to motor vehicle accidents (MVA) vs. participants exposed to other life – threatening accidents.

Results

Participants exposed to MVA and those exposed to other accidents had significantly different scores in 7 RFL items. Scores were high in 4 out of 6 RFL subscales for both samples and in most items comprising these subscales, while in the other 2 subscales and in some items comprising them scores were low.

Conclusions

Low fear of death, physical suffering and social disapproval emerge as risk factors in persons exposed to life – threatening accidents. Love of life, courage in life and hope for the future are important resilience factors after exposure to various types of life – threatening accidents. Survival and active coping beliefs promote resilience especially after motor vehicle accidents. Coping with uncertainty are more likely to foster resilience after other types of life – threatening accidents. Attachment of the accident victim to family promotes resilience mostly after MVA, while perceived attachment of family members to the victim promotes resilience after other types of accidents.

Keywords: life – threatening accidents, risk, resilience, coping

Background and aims

Different definitions given to the construct of resilience encompass the shared perspective of an adaptive, effective functioning of the person confronted with adversity. Individual, familial, organizational, societal, and cultural contexts foster resilience as dynamic and flexible structure of genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors [1].

Recent studies ascertain several psychosocial factors promoting resilience after trauma exposure: optimism (positive projection in the future), cognitive flexibility (the ability to reappraise and reframe trauma and failure), active coping (active seeking of resources and help), and personal moral compass (altruism, spirituality, purpose in life and adaptive positive beliefs) [2]. Trauma research increasingly addresses resilience and risk in the context of war exposure [3, 4], natural disasters [5, 6], interpersonal violence [7] or child abuse [8]. However, psychological consequences of accidental traumatic events are often underestimated or untimely addressed [9] and data regarding resilience after life – threatening accidental trauma is still scarce [10].

Some studies report poorer coping skills and an excess of psychological symptoms in injured workers [11]. Other authors endorse external locus of control, optimism, active coping and positive affect as resilience factors after work – related accidents [12]. Studies ascertain the negative impact of motor vehicle accidents (MVA) on the structure, interactions and dynamics of the traumatized person’s family and household [13], or address internal and external mediators of the posttraumatic stress symptoms (PSS) after MVA [14, 15].

The few Romanian studies concerning persons exposed to accidents assess PSS in train operators witnessing railway suicides [16], resilience against suicide in persons exposed to accidents [17], or introduce brief PSS screening measures for accident victims [18].

We address resilience factors related to life – threatening accidental trauma with complex consequences in an adult civilian population through a cross – sectional, observational study. The aim of the current study is to comparatively assess adaptive, life – promoting factors in persons exposed to motor vehicle accidents (MVA) vs. persons exposed to other types of accidents, and to identify psychological factors of resilience and vulnerability in this context of trauma exposure.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Cluj –Napoca, Romania, Approval No. 296/28 July 2014.

The study focused on life – threatening, accidental trauma not resulting from interpersonal aggression. We selected recruitment centers which provide comprehensive acute and follow-up medical care for adult patients exposed to trauma: the Plastic surgery and reconstructive microsurgery Clinic and the Neurology Rehabilitation Clinic of the Clinical Rehabilitation Hospital Cluj-Napoca, and the Emergency Unit of the Cluj County Emergency Hospital, respectively.

A convenient, non – probabilistic recruitment procedure was used, which was implemented between July 29th 2014 and July 15th 2015. Recruiters identified 305 eligible patients exposed to the aforementioned types of life events in the recruitment centers and contacted 257 of those patients. 137 patients (53.30% of those contacted) signed the informed consent for participation in the study. 108 participants (78.83% of those recruited) completed all study assessments: 43 participants (39.82%) from the Clinical Rehabilitation Hospital Cluj-Napoca, Romania – Neurology Rehabilitation Clinic, 25 from the Clinical Rehabilitation Hospital Cluj-Napoca, Romania – Plastic surgery and reconstructive microsurgery Clinic (23.14%), and 40 from the Emergency Unit – Cluj County Emergency Hospital, respectively (37.04%).

For the purpose of this study, authors excluded data from 15 of the 108 participants, due to the fact that they reported multiple exposure to accidents or exposure to sexual or non-sexual aggression prior to the accident exposure. The remaining sample consisted of 93 participants exposed to life – threatening accidents (see Table I).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical features of the study participants

| SAMPLE PARAMETERS | EXPOSED TO MVA | EXPOSED TO OTHER LIFE – TREATENING ACCIDENTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 59 (63.44%) | 34 (36.56%) | ||

| Age in years* | 35.05 (±11.81) | 40.12 (±14.09) | ||

| Gender | Male 30 (50.8%) | Female 29 (49.2%) | Male 17 (50%) | Female 17 (50%) |

| Housing | Urban 53 (89.8%) | Rural 6 (10.2%) | Urban 26 (76.5%) | Rural 8 (23.5%) |

| Permanent disability caused by the assessed traumatic event | Yes 26 (44.1%) | No 33 (55.9%) | Yes 21 (61.8%) | No 13 (38.2%) |

Data presented as mean (±standard deviation)

Measures

The study used the following clinical instruments:

-

LINEHAN REASONS FOR LIVING SCALE (RFL) is a self-report with 48 items grouped in 6 subscales – Survival and Coping Beliefs (SCB, items 2, 3, 4, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 17, 19, 20, 22, 24, 25, 29, 32, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45), Responsibility to Family (RF, items 1, 7, 9, 16, 30, 47, 48), Child-related Concerns (CC, items 11, 21, 28), Fear of Suicide (FS, items 6, 15, 18, 26, 33, 38, 46), Fear of Social Disapproval (FSD, items 31, 41, 43), Moral Objections (MO, items 5, 23, 27, 34) – see Table II.

The importance of each item as a reason to stay alive is rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 6: 1 (not at all important), 2 (quite unimportant), 3 (somewhat unimportant), 4 (somewhat important), 5 (quite important), 6 (very important).

This complex tool evaluates individual cognitions, beliefs and values, focusing on the assessment of individual strengths and vulnerabilities. Although RFL was initially developed for suicidal subjects, the original instructions provide the possibility to employ this tool on various types of populations, exploring the reasons why the individual would not consider committing suicide if someone else mentioned suicide as an option. [19]. The resilience conferred by strong reasons to live [20] supports the use of this tool for the purpose of this study.

LIFE EVENTS CHECKLIST (LEC) is an inventory of 17 types of traumatic life events which might generate posttraumatic stress in persons exposed (see Table III), originally developed concurrently with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS). LEC has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties when evaluating consistency of respondents’ exposure to traumatic events [21]. For the purpose of this study, participants chose one of the following answer options for each type of event: ‘never experienced it’, or ‘I experienced it’.

Table II.

Reasons for Living Scale (RFL, Copyright 1996 M. M. Linehan).

| Item no. | Item content |

|---|---|

| 1 | I have a responsibility and commitment to my family. |

| 2 | I believe I can learn to adjust or cope with my problems. |

| 3 | I believe I have control over my life and destiny. |

| 4 | I have a desire to live. |

| 5 | I believe only God has the right to end a life. |

| 6 | I am afraid of death. |

| 7 | My family might believe I did not love them. |

| 8 | I do not believe that things get miserable or hopeless enough that I would rather be dead. |

| 9 | My family depends upon me and needs me. |

| 10 | I do not want to die. |

| 11 | I want to watch my children as they grow. |

| 12 | Life is all we have and is better than nothing. |

| 13 | I have future plans I am looking forward to carrying out. |

| 14 | No matter how badly I feel, I know that it will not last. |

| 15 | I am afraid of the unknown. |

| 16 | I love and enjoy my family too much and could not leave them. |

| 17 | I want to experience all that life has to offer and there are many experiences I haven’t had yet which I want to have. |

| 18 | I am afraid that my method of killing myself would fail. |

| 19 | I care enough about myself to live. |

| 20 | Life is too beautiful and precious to end it. |

| 21 | It would not be fair to leave the children for others to take care of. |

| 22 | I believe I can find other solutions to my problems. |

| 23 | I am afraid of going to hell |

| 24 | I have a love of life. |

| 25 | I am too stable to kill myself. |

| 26 | I am a coward and do not have the guts to do it. |

| 27 | My religious beliefs forbid it. |

| 28 | The effect on my children could be harmful. |

| 29 | I am curious about what will happen in the future. |

| 30 | It would hurt my family too much and I would not want them to suffer. |

| 31 | I am concerned about what others would think of me. |

| 32 | I believe everything has a way of working out for the best. |

| 33 | I could not decide where, when, and how to do it. |

| 34 | I consider it morally wrong. |

| 35 | I still have many things left to do. |

| 36 | I have the courage to face life. |

| 37 | I am happy and content with my life. |

| 38 | I am afraid of the actual “act” of killing myself (the pain, blood, violence). |

| 39 | I believe killing myself would not really accomplish or solve anything. |

| 40 | I have hope that things will improve and the future will be happier. |

| 41 | Other people would think I am weak and selfish. |

| 42 | I have an inner drive to survive. |

| 43 | I would not want people to think I did not have control over my life. |

| 44 | I believe I can find a purpose in life, a reason to live. |

| 45 | I see no reason to hurry death along. |

| 46 | I am so inept that my method would not work. |

| 47 | I would not want my family to feel guilty afterwards. |

| 48 | I would not want my family to think I was selfish or a coward. |

Table III.

Life Events Checklist (LEC).

| Item no. | Traumatic event |

|---|---|

| 1 | Natural disaster (for example, flood, hurricane, tornado, earthquake) |

| 2 | Fire or explosion |

| 3 | Transportation accident (for example, car accident, boat accident, train wreck, plane crash) |

| 4 | Serious accident at work, home, or during recreational activity |

| 5 | Exposure to toxic substance (for example, dangerous chemicals, radiation) |

| 6 | Physical assault (for example, being attacked, hit, slapped, kicked, beaten up) |

| 7 | Assault with a weapon (for example, being shot, stabbed, threatened with a knife, gun, bomb) |

| 8 | Sexual assault (rape, attempted rape, made to perform any type of sexual act through force or threat of harm) |

| 9 | Other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experience |

| 10 | Combat or exposure to a war-zone (in the military or as a civilian) |

| 11 | Captivity (for example, being kidnapped, abducted, held hostage, prisoner of war) |

| 12 | Life-threatening illness or injury |

| 13 | Severe human suffering |

| 14 | Sudden, violent death (for example, homicide, suicide) |

| 15 | Sudden, unexpected death of someone close to you |

| 16 | Serious injury, harm, or death you caused to someone else |

| 17 | Any other very stressful event or experience |

Scoring and assessment procedure

Authors received permission from RFL and LEC authors to use the scales in the study, then translated and adapted the scales into Romanian. The participants included in the study reported single life – threatening exposure to events referenced in LEC items 2 (burns), 3 (MVA), 4 (domestic, work or sports – related accidents) or 5 (accidental chemical burns).

Total RFL score was computed as the sum of item scores; scores for each RFL subscale were computed as sums of subscale items [19].

Scores for individual RFL items, RFL total scores and scores for all 6 RFL subscales were comparatively assessed in participants exposed to MVA vs. participants exposed to other life – threatening accidents.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Pack for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 22.0. Mann – Whitney U test was used for discrete variables, to test for differences between 2 samples. For continuous variables, T – test for independent samples was used to compare means between 2 samples and Levene’s test was used to test for variances between samples.

Results

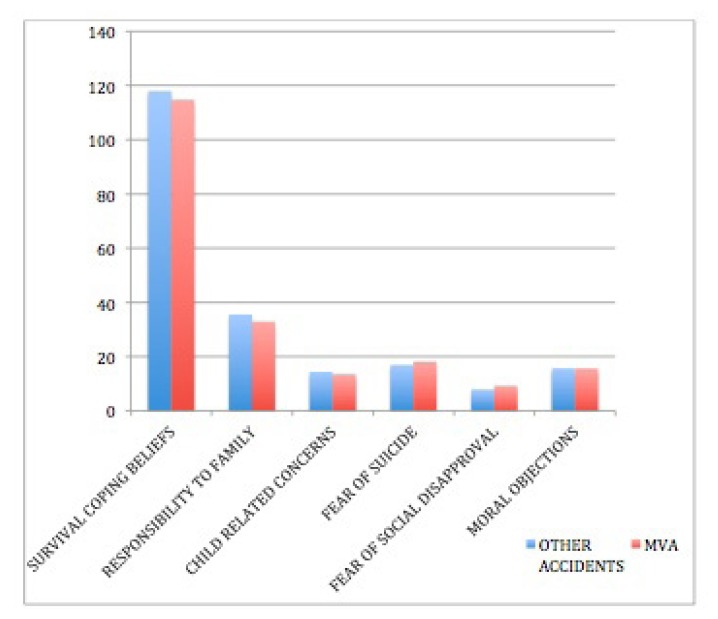

RFL total scores (p = .587, t – test for independent samples) and scores for the 6 RFL subscale scores were not significantly different in participants exposed to MVA vs. those exposed to other accidents (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean scores for the 6 RFL subscales in sample participants exposed to MVA vs. other accidents.

Participants exposed to MVA and those exposed to other accidents had significantly different scores in 7 RFL items: 4 belonging to the SCB Subscale (see Figure 2), 2 belonging to the RF subscale (see Figure 3) and 1 belonging to the FS subscale, respectively (See Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Mean scores for 4 items from the Survival and Coping Beliefs Subscale in sample participants exposed to MVA vs. other accidents.

Figure 3.

Mean scores for 2 items from the Responsibility to Family subscale in sample participants exposed to MVA vs. other accidents.

Figure 4.

Mean scores for 1 item from the Fear of Suicide subscale in sample participants exposed to MVA vs. other accidents.

Scores for the remaining items rendered no significant difference across samples (see Table IV).

Table IV.

Scores for 41 items of the RFL scale in participants exposed to MVA vs. exposed to other accidents.

| Item no. | Item content | Participants exposed to MVA* | Participants exposed to other accidents* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | I believe I can learn to adjust or cope with my problems. | 5.17 (±1.275) | 5.53 (±1.08) |

| 3 | I believe I have control over my life and destiny. | 5.07 (±1.4) | 4.85 (±1.56) |

| 4 | I have a desire to live. | 5.39 (±1.246) | 5.71 (±0.938) |

| 5 | I believe only God has the right to end a life. | 4.71 (±1.752) | 5.18 (±1.623) |

| 6 | I am afraid of death. | 3.47 (±1.654) | 2.97 (±1.915) |

| 7 | My family might believe I did not love them. | 4.32 (±1.833) | 4.15 (±2.285) |

| 8 | I do not believe that things get miserable or hopeless enough that I would rather be dead. | 4.86 (±1.514) | 5.12 (±1.61) |

| 9 | My family depends upon me and needs me. | 4.95 (±1.443) | 5.38 (±1.349) |

| 10 | I do not want to die. | 5.02 (±1.526) | 5.09 (±1.747) |

| 11 | I want to watch my children as they grow. | 4.68 (±1.898) | 5.15 (±1.778) |

| 12 | Life is all we have and is better than nothing. | 4.93 (±1.461) | 5.00 (±1.557) |

| 13 | I have future plans I am looking forward to carrying out. | 5.08 (±1.381) | 5.03 (±1.446) |

| 15 | I am afraid of the unknown. | 3.1 (±1.572) | 3.03 (±1.915) |

| 17 | I want to experience all that life has to offer and there are many experiences I haven’t had yet which I want to have. | 5.15 (±1.297) | 5.12 (±1.493) |

| 19 | I care enough about myself to live. | 5.07 (±1.507) | 5.18 (±1.466) |

| 20 | Life is too beautiful and precious to end it. | 5.36 (±1.047) | 5.24 (±1.394) |

| 21 | It would not be fair to leave the children for others to take care of. | 4.46 (±2.104) | 4.82 (±1.961) |

| 22 | I believe I can find other solutions to my problems. | 5.19 (±1.266) | 5.47 (±1.187) |

| 23 | I am afraid of going to hell | 2.93 (±1.99) | 2.82 (±2.167) |

| 25 | I am too stable to kill myself. | 4.78 (±1.703) | 4.65 (±1.773) |

| 26 | I am a coward and do not have the guts to do it. | 2.24 (±1.755) | 2.00 (±1.809) |

| 27 | My religious beliefs forbid it. | 3.75 (±1.953) | 3.94 (±2.242) |

| 28 | The effect on my children could be harmful. | 4.32 (±2.121) | 4.38 (±2.216) |

| 29 | I am curious about what will happen in the future. | 4.64 (±1.606) | 4.97 (±1.507) |

| 30 | It would hurt my family too much and I would not want them to suffer. | 4.98 (±1.613) | 5.41 (±1.395) |

| 31 | I am concerned about what others would think of me. | 3.08 (±1.832) | 2.5 (±1.895) |

| 32 | I believe everything has a way of working out for the best. | 4.71 (±1.439) | 4.94 (±1.575) |

| 33 | I could not decide where, when, and how to do it. | 2.25 (±1.738) | 1.97 (±1.883) |

| 34 | I consider it morally wrong. | 4.2 (±1.954) | 3.71 (±2.25) |

| 35 | I still have many things left to do. | 5.19 (±1.279) | 5.26 (±1.524) |

| 37 | I am happy and content with my life. | 5.02 (±1.266) | 4.79 (±1.754) |

| 38 | I am afraid of the actual “act” of killing myself (the pain, blood, violence). | 2.8 (±1.954) | 3.12 (±2.226) |

| 39 | I believe killing myself would not really accomplish or solve anything. | 4.54 (±1.968) | 4.38 (±2.202) |

| 41 | Other people would think I am weak and selfish. | 2.85 (±1.91) | 2.56 (±2.092) |

| 42 | I have an inner drive to survive. | 5.1 (±1.423) | 5.09 (±1.485) |

| 43 | I would not want people to think I did not have control over my life. | 3.2 (±2.007) | 2.76 (±2.075) |

| 44 | I believe I can find a purpose in life, a reason to live. | 5.14 (±1.345) | 5.47 (±1.212) |

| 45 | I see no reason to hurry death along. | 4.73 (±1.779) | 4.71 (±1.978) |

| 46 | I am so inept that my method would not work. | 1.95 (±1.525) | 2.15 (±1.925) |

| 47 | I would not want my family to feel guilty afterwards. | 4.37 (±1.982) | 4.62 (±2.104) |

| 48 | I would not want my family to think I was selfish or a coward. | 3.78 (±2.018) | 4.44 (±2.077) |

Data presented as mean (±standard deviation)

Discussion

Authors identified 7 RFL items in which differences across samples were statistically significant. In 6 out of these items, scores were lower in participants exposed to MVA than in participants exposed to other accidents. The content of the aforementioned items reflects love for life, positive approach of hardships, optimistic outlook of the future and responsibility for the family. However, these differences lack clinical significance; additionally, there were high scores for these items in both samples. This suggests that all participants express resilience factors related to optimism, cognitive flexibility and responsibility for the family.

These data are in agreement with studies which underline optimism and cognitive flexibility as resilience factors in the wake of life – threatening accidents [2,22]. Also, responsibility to family as resilience factor in this context of trauma exposure concurs with recent data from a study on migrating youth, in a different cultural and trauma exposure context than our research [23].

Low scores in both samples for the remaining item, from the FS subscale, suggest that fear that the suicide method would fail is not a resilience factor for either of the samples. Scores in this item are higher in participants exposed to MVA, but differences are clinically insignificant.

For the other 41 items of RFL, differences across samples carry no statistical or clinical significance.

Scores for the remaining 20 items in the SCB subscale ascertain that in both samples resilience factors related to effective coping are highly important. In some items, MVA survivors scored higher than counterparts, supporting a higher tendency, compared with survivors of other accidents, to endorse resilience factors related to life satisfaction, stability across time, effective control of the context and consequences and positive expectations about the future. Items in which MVA survivors scored lower reflect a lower tendency of participants exposed to MVA, compared to those exposed to other types of accidents, to endorse resilience factors related to willingness (rational rather than emotional) to live life as it is and will be, effective coping with uncertainty. Some of these data concur with findings from studies about uncertainty and resilience in oncological patients [24], and posttraumatic growth after accidents [25].

In both samples, score values for 4 out of the remaining 5 items of the RF subscale reflect the high importance of resilience factors related to family. For MVA survivors, fear of being perceived as lacking love for family tends to be more important. Perception of the family as depending on them and emotionally affected by their actions tends to be more important in participants exposed to other types of accidents. Regarding the fear of being perceived as selfish by family, MVA survivors tend to endorse a lack of importance as resilience factors; conversely, persons exposed to other accidents tend to endorse it as resilience factor. In this respect, other studies ascertain family relationships, boundaries, and emotional functioning of family members as resilience resources after child abuse [26].

Scores for items of the CC subscale also reflect the high importance of resilience factors related to children in all participants – with a lower tendency of participants exposed to MVA vs. counterparts to endorse those factors. Conversely, scores for items of the FS and FSD subscales reflect a low importance in all participants of resilience factors related to internal and external evaluations of the person’s effectiveness in dealing with death, failure and uncertainty. Participants exposed to other accidents tend to consider social disapproval as more unimportant than their counterparts. Also, fear of facing death or deciding its context tend to be less important in participants exposed to other accidents, while fear of uncertainty and fear of potential physical distress tend to be more unimportant in participants exposed to MVA. Some of these findings contradict data from other studies, on medical staff exposed to imminent death of patients, regarding the importance of dealing with death and failure [27]. On the other hand, studies on terminal patients report enduring pain as an important resource in coping with imminent death [28].

Surrendering to a divine higher power emerges as an important resilience factor for both samples, with persons exposed to other accidents showing a higher tendency than counterparts to endorse it. Death as morally wrong emerges as important for participants exposed to MVA and unimportant for the others. Fear of going to hell and religious interdictions of suicide are unimportant as resilience factors for both samples; the former carries less importance for persons exposed to other accidents, while the latter – for those exposed to MVA. These findings are different from those of studies assessing the role of spirituality and religiosity as resilience factors in patients with chronic illness [29].

The overall importance of positive beliefs regarding abilities to cope with life, adversity and uncertain future is supported in both samples by high SCB subscale scores. External resilience factors related to family and children are also consistently endorsed by all participants. Moral views concerning suicide as escape from adversity are also somewhat important as resilience factors in all participants. On the other hand, external negative assessments of failure in managing adversity are not endorsed as resilience factors by study participants, regardless of type of accident. This could suggest that resilience fostered through feedbacks from community does not carry a role after these types of trauma. Moreover, low fear of death and physical distress appears as risk factor in this context. This may suggest either courage in the face of life – threatening and physically harming adversity, or increased tolerance to death and physical suffering, possibly leading to increased capability for suicide.

Conclusions

Low fear of death, physical suffering and social disapproval emerge as risk factors in persons exposed to life – threatening accidents.

Love of life, courage in life and hope for the future are important resilience factors after exposure to various types of life – threatening accidents.

Survival and active coping beliefs promote resilience especially after motor vehicle accidents.

Coping with uncertainty are more likely to foster resilience after other types of life – threatening accidents.

Attachment of the accident victim to family promotes resilience mostly after MVA, while perceived attachment of family members to the victim promotes resilience after other types of accidents.

Acknowledgements

This paper was published under the frame of European Social Fund, Human Resources Development Operational Programme 2007–2013, project no. POSDRU/159/1.5/S/138776.

The study was developed independently from the funding source.

The authors wish to kindly thank Professor Marsha M. Linehan (University of Washington, Behavioral Research and Therapy Clinics) and the National Center for PTSD (Department of veterans Affairs, USA) for providing the original versions of the scales used in this research. The authors also thank Professor Alexandru Georgescu, MD, PhD, and Professor Angelo Bulboacă, MD, PhD for providing the clinical setting for recruiting participants for the study, and Marius Nicula, Iulian Novac and Cosmin Rusneac (Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca) for their contribution as recruiters.

References

- 1.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014 Oct;1:5. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iacoviello BM, Charney DS. Psychosocial facets of resilience: implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014 Oct;1:5. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.23970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litz BT. Resilience in the aftermath of war trauma: a critical review and commentary. Interface Focus. 2014 Oct 6;4(5):20140008. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2014.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisen SV, Schultz MR, Glickman ME, Vogt D, Martin JA, Osei-Bonsu PE, et al. Postdeployment resilience as a predictor of mental health in operation enduring freedom/operation iraqi freedom returnees. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):754–761. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni C, Chow MC, Jiang X, Li S, Pang SM. Factors associated with resilience of adult survivors five years after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 26;10(3):e0121033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe SR, Sampson L, Gruebner O, Galea S. Psychological resilience after Hurricane Sandy: the influence of individual- and community-level factors on mental health after a large-scale natural disaster. PLoS One. 2015 May 11;10(5):e0125761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boxer P, Sloan-Power E. Coping with violence: a comprehensive framework and implications for understanding resilience. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2013;14(3):209–221. doi: 10.1177/1524838013487806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domhardt M, Münzer A, Fegert JM, Goldbeck L. Resilience in Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(4):476–493. doi: 10.1177/1524838014557288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Undavalli C, Das P, Dutt T, Bhoi S, Kashyap R. PTSD in post-road traffic accident patients requiring hospitalization in Indian subcontinent: A review on magnitude of the problem and management guidelines. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2014;7(4):327–331. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.142775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osenbach JE, Lewis C, Rosenfeld B, Russo J, Ingraham LM, Peterson R, et al. Exploring the longitudinal trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorder in injured trauma survivors. Psychiatry. 2014;77(4):386–397. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghisi M, Novara C, Buodo G, Kimble MO, Scozzari S, Di Natale A, et al. Psychological distress and post-traumatic symptoms following occupational accidents. Behav Sci (Basel) 2013;3(4):587–600. doi: 10.3390/bs3040587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roesler ML, Glendon AI, O’Callaghan FV. Recovering from traumatic occupational hand injury following surgery: a biopsychosocial perspective. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(4):536–546. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez-Núñez R, Pelcastre-Villafuerte B, Híjar M, Avila-Burgos L, Celis A. A qualitative approach to the intangible cost of road traffic injuries. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012;19(1):69–79. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2011.603155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Kao TC, Vance K, et al. Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:589–595. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irish LA, Gabert-Quillen CA, Ciesla JA, Pacella ML, Sledjeski EM, Delahanty DL. An examination of PTSD symptoms as a mediator of the relationship between trauma history characteristics and physical health following a motor vehicle accident. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(5):475–482. doi: 10.1002/da.22034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doroga C, Băban A. Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic symptoms for train drivers involved in railway incidents. Clujul Med. 2013;86(2):144–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herţa DC, Cozman D. Protective factors against suicide in persons traumatized by accidents. Rom J Psychiatr. 2013;15(1):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herţa DC, Nemeş B, Cozman D. Screening methodology for posttraumatic stress disorder through self-assessment scales. Journal of Cognitive & Behavioral Psychotherapies. 2013;13(1):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Nielsen SL, Chiles JA. Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the reasons for living inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(2):276–286. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kralik KM, Danforth WJ. Identification of coping ideation and strategies preventing suicidality in a college-age sample. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22(2):167–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment. 2004;11(4):330–341. doi: 10.1177/1073191104269954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quale AJ, Schanke AK. Resilience in the face of coping with a severe physical injury: a study of trajectories of adjustment in a rehabilitation setting. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55:12–22. doi: 10.1037/a0018415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponizovsky-Bergelson Y, Kurman J, Roer-Strier D. Adjustment enhancer or moderator? The role of resilience in postmigration filial responsibility. J Fam Psychol. 2015;29(3):438–446. doi: 10.1037/fam0000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beusterien K, Tsay S, Gholizadeh S, Su Y. Real-world experience with colorectal cancer chemotherapies: patient web forum analysis. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013 Oct 10;7:361. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Wang H, Wang J, Wu J, Liu X. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic growth in accidentally injured patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20(1):3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vermeulen T, Greeff AP. Family Resilience Resources in Coping With Child Sexual Abuse in South Africa. J Child Sex Abus. 2015;24(5):555–571. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2015.1042183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloomer MJ, O’Connor M, Copnell B, Endacott R. Nursing care for the families of the dying child/infant in paediatric and neonatal ICU: nurses’ emotional talk and sources of discomfort. A mixed methods study. Aust Crit Care. 2015;28(2):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho AH, Chan CL, Leung PP, Chochinov HM, Neimeyer RA, Pang SM, et al. Living and dying with dignity in Chinese society: perspectives of older palliative care patients in Hong Kong. Age Ageing. 2013;42(4):455–461. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha AC, Ciosak SI. Chronic disease in the elderly: spirituality and coping. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2014;48(Spec 2):87–93. doi: 10.1590/S0080-623420140000800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]