Abstract

Background

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) presents with hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and thrombotic microangiopathy of the kidney and usually results from Shiga-toxin induced activation of the alternative complement pathway. Gastroenteritis is a common feature of the Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli HUS, referred to as STEC-HUS. An inherited or acquired complement dysregulation may lead to HUS referred to as non-STEC or atypical (a)HUS. Although gastroenteritis is not a common presentation of aHUS, some patients develop ischemic colitis and may be misdiagnosed as acute appendicitis or acute ulcerative colitis (UC).

Case Diagnosis –Treatment

We present a patient with low circulating complement (C) 3 levels who developed aHUS in the course of chronic active UC. Resolution of renal and gastrointestinal manifestations in response to treatment with eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against terminal C5 protein suggests the role of alternative complement in the pathogenesis of both, aHUS and UC.

Conclusion

This case illustrates that dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway may manifest in other organs besides the kidney and that the circulating C3 levels do not correlate with the disease activity or the clinical response to eculizumab.

Keywords: Hemolytic–uremic syndrome (HUS), thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), ulcerative colitis (UC), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), acute kidney injury (AKI), membrane attack complex (MAC)

1. INTRODUCTION

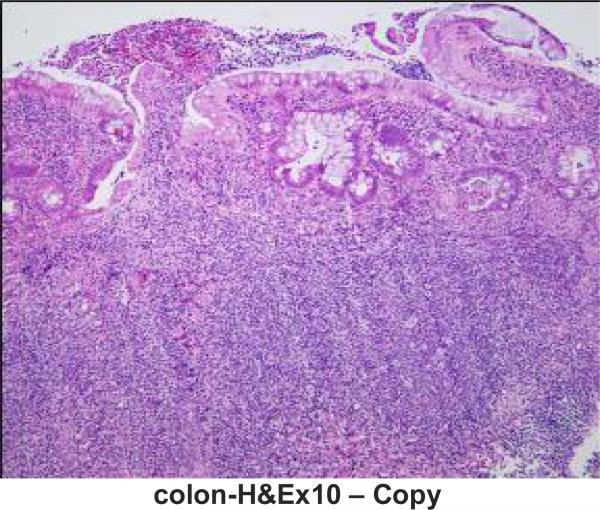

A 16-year-old Caucasian male with a 4-year history of chronic active ulcerative colitis presented with severe symptomatic anemia, thrombocytopenia, intravascular hemolysis, acute kidney injury, nephritis, and decreased C3 levels. Three months earlier he was hospitalized for UC flare (Fig. 1a) and worsening microcytic anemia (Hb 8.2 mg/dL) and his symptoms responded to treatment with intravenous (IV) methyprednisolone and packed red blood cells (RBC) transfusion. After hospital discharge he was continued on a prednisone taper and started on 6-mercaptopurine (6MP; 1.7 mg/kg/day). One month later he developed a flu-like illness with high fever and was treated with cephalexin for possible bacterial sinusitis. Routine monitoring laboratories, including complete blood cell count and serum chemistries were normal. Over the course of the following two weeks he developed increased stool output, bloody stools, decreased appetite, fatigue, shortness of breath, and pallor. He had no urinary symptoms and no dark discoloration of urine. On arrival to the hospital he had increased blood pressure and tachycardia. Laboratory studies were remarkable for severe anemia (Hb 4.4 mg/dL), neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count 0.615 × 109/L), decrease in baseline platelet count to 143 × 105/mL, doubling of serum creatinine from baseline (1.4 mg/dL), increased LDH (428 IU/L), hypoalbuminemia (2.7 mg/dL), and elevated inflammatory markers (CRP 3.7 mg/dl, ESR 113 mm/h). Urinalysis revealed microscopic hematuria, 300 mg/dL protein and no pyuria. He was transfused with packed RBCs, started on IV fluids and methyprednisolone, and 6MP was discontinued. His clinical symptoms improved; however, he continued to have frequent Hemoccult positive stools. Evaluation of the peripheral blood smear, worsening thrombocytopenia (the lowest count was 38 × 105/ml), rising LDH, decreased haptoglobin, and elevated free plasma hemoglobin were consistent with intravascular hemolysis (Table 1). Serum creatinine remained elevated despite hydration, and two 24-hour urine collections confirmed nephrotic range proteinuria. Serial review of urine microscopy showed interval development of RBC casts. Circulating complement (C) 3 was decreased and C4 was normal (Table 1). Stool studies were negative for E. coli O157:H7 by sorbitol-MacConkey agar and Shiga toxin I and II by PCR. Other workup was unremarkable except for transiently elevated homocysteine levels (Table 1).

Fig. 1. (a).

Light microscopy of colon biopsy specimen demonstrating chronic active colitis. Thickened muscularis mucosae, lamina propria fibrosis, crypt distortion, and heavy lymphoid and plasma cell component as well as stromal neutrophils and crypt abscess formation (arrow). (Hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification × 100). Specimen was obtained 3 months before presentation with aHUS

Table 1.

The laboratory test results

| Direct coombs | Negative |

| Indirect coombs | Negative |

| Haptoglobin | <15 mg/dL (30-200) |

| LDH | 428-735 IU/L (115-257) |

| Free plasma hemoglobin | 11.7 (<6) |

| ESR | 113 mm/h (< 20) |

| CRP | 3.7 mg/dL (0.04-0.79) |

| C3 | 49 mg/dL (82-163) |

| C4 | 18 mg/dL (14-41) |

| PNH flow cytometry | Negative |

| ADAMTS13 activity | 85% (>68) |

| ADAMTS13 inhibitor | 15% (<30) |

| Ristocetin cofactor | 1.77 U/mL(0.5-1.5) |

| Russel viper venom time | Normal |

| APC resistance | 3.4 (2.1-3) |

| PT/PTT/INR | Normal |

| Thrombin | Normal |

| Protein C | Normal |

| Protein S | 170% (58-128) |

| Factor X | Normal |

| Antithrombin III | Normal |

| Homocysteine | 19.8 umol/L (5.5-13.8) |

| MTHFR gene | 677C>T variant, heterozygous |

| Prothrombin gene | No 20210G>A mutation |

| ANA | Negative |

| ANCA | Negative |

| LAC/vWD | Negative |

| ASO titer | Negative |

| anti-dNAse B antibody | Negative |

| Anti-dsDNA antibody | Negative |

| CFH level | 256 mcg/ml (160-412) |

| Anti-CFH antibody | Negative |

| CFH coding region | No disease causing mutations |

| MLPA for CFHR3-1 deletion | Negative |

| CFB level | 205.6 mcg/ml (127.6-278.5) |

| CFB coding region | No disease causing mutations |

| CFI level | 44.0 mcg/ml (29.3-58.5) |

| CFI coding region | No disease causing mutations |

| MCP | Normal |

| MCP coding region | No disease causing mutations |

| ELISA for TCC | Negative (no TCC consumption) |

| C3 coding region | No disease causing mutations |

| Thrombomodulin gene | No disease causing mutations |

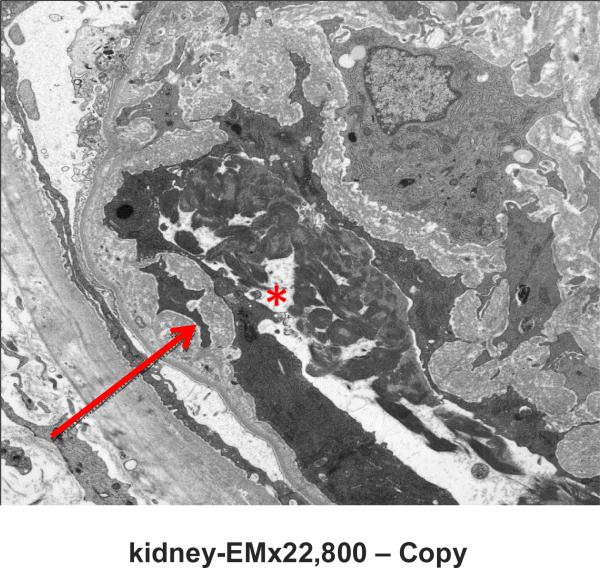

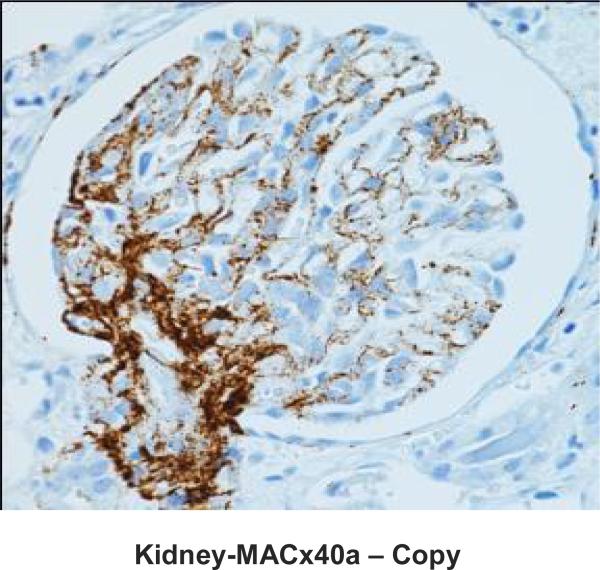

Native kidney biopsy showed widespread and acute thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) without chronic changes (Fig. 1b & c). Immunostaining for Membrane Attack Complex (MAC; C5b-9 complement) showed heavy granular deposition along the glomerular basement membranes of most glomeruli, with some mesangial and afferent arteriolar staining and staining of the tubular basement membrane (Fig. 1d). A working diagnosis of atypical HUS was made. After confirmation of immunization with the pneumococcal and meningococcal series, the patient received the first dose of eculizumab (900 mg). Penicillin was started for prophylaxis against Neisseria meningitidis serotype B. Laboratory studies did not reveal the underlying cause of aHUS (Table 1). Soluble MAC and anti-CFH antibodies were not detected before starting eculizumab, genetic studies on Complement Factor (CF)H, CFI, CFB, CFHR1-3, MCP, C3 and thrombomodulin did not reveal disease causing mutations.

Fig. 1. (b).

Light microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen demonstrating acute thrombotic microangiopathy without chronic findings of glomerulosclerosis or interstitial fibrosis. There is glomerular capillary dilatation, increased mesangial matrix, as well as platelet and fibrin thrombi in glomerular loops with focal and segmental necrosis. There is extension to afferent arterioles with fibrinoid change. RBC fragments are present in the glomerulus. Tubules have large resorption droplets, are often dilated with RBC casts. The interstitium has focal RBC (Hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification × 400)

Fig. 1. (c).

Electron microscopy of the glomerular capillary loop. Fibrin is present in a capillary lumen (asterisk) and there is fibrillar material that separates the endothelial cell from the capillary basement membrane (arrow) (Original magnification × 22,800)

Fig. 1. (d).

Immunostaining (antibody DAKO #M0777, clone aE11) for membrane attack complex (MAC; C5b-9 complement) of kidney biopsy specimen demonstrating heavy granular deposition along the glomerular basement membranes with some mesangial and afferent arteriolar staining. (Original magnification × 400)

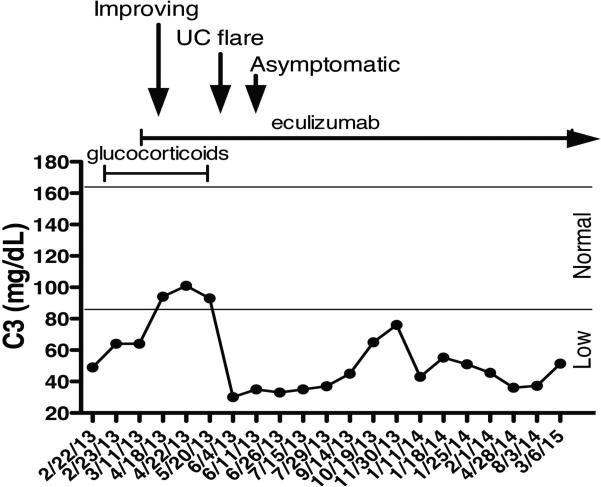

He was discharged home on prednisone, metronidazole, balsalazide, penicillin, iron, and multivitamin. He received three additional weekly doses of eculizumab (900 mg) followed by every other week maintenance (1,200 mg). Clinical symptoms continued to improve. All blood counts and markers of inflammation and hemolysis normalized. C3 normalized briefly but subsequently remained low (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fluctuating levels of circulating complement (C) 3. The horizontal lines delineate the normal C3 levels. Glucocorticosteroids were started on 2/23/13 and were tapered off by 5/7/13. Eculizumab was started on 3/5/13. Additional medications were metronidazole, balsalazide, penicillin, iron, and multivitamin. The patient started to improve within days after starting eculizumab but experienced a short UC flare on 5/20/13. He became asymptomatic within a week without additional therapy. The patient has been asymptomatic, normotensive and has had normal kidney function during the 24 month follow-up while remaining on eculizumab

Proteinuria resolved and serum creatinine returned to baseline. RBC casts were no longer present and microscopic hematuria resolved. Six weeks after initiation of eculizumab the patient experienced one brief UC flare demonstrated by increased stool output, bloody stools and elevated calprotectin (1,661.9 mcg/g) without evidence of hemolysis or AKI. The gastrointestinal symptoms resolved and calprotectin decreased to normal (<160 mcg/g) within a week with no additional therapy. Subsequently, the patient has been asymptomatic and normotensive despite having persistently low C3 levels while remaining on eculizumab. He was able to resume full activity including school attendance and participation in sports.

2. DISCUSSION

aHUS represents 5-10% of HUS in children but the majority of HUS in adults [1]. While the alternative complement gene mutations predispose to aHUS additional triggers are necessary for the devastating disease manifestations including platelet activation, endothelial damage, and microthrombi formation known as TMA [1]. The triggers that account for the episodic nature of aHUS are poorly understood [2,3]. Activation of the alternative complement can be caused by infectious agents, malignancy, bone marrow or solid organ transplantation and chemotherapeutic or immunosuppressive agents [4,5], systemic illness (systemic lupus erythematous, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, scleroderma) [6,7], severe pre-ecclampsia [8], hyperhomocystinemia [9,10], mutations in the thrombomodulin (THMB) [11] or diacylglycerol kinase ε (DGKE) gene [12]. In some of these disorders TMA may result from factors outside of the complement system such as thrombophilia [9-12]. The preceding flu-like illness in the presented patient may have precipitated aHUS. By contrast, 6MP has no reported association with aHUS. Hyperhomocystinemia is an independent risk factor for intravascular thrombosis [13] and for mucosal microvascular activation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including UC [14]. Many patients with IBD have elevated homocystine levels due to nutritional deficiencies or genetic polymorphisms of enzymes linked to homocysteine metabolisms [2,3]. Thus, elevated homocysteine may have been a trigger or a modifier of aHUS. Alternatively, it may have been the result of aHUS because homocysteine levels are increased in patients with renal failure [15]. The presented patient is heterozygous for the thermolabile variant 677C>T of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) necessary for re-methylation of homocysteine to methionine. However, only a homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the MTHFR gene was shown to increase homocysteine level. Further genetic testing was not performed due to normalization of the homocysteine level (7.4 μmol/L). Overall, the genetic factors leading to pathologic activation of the alternative complement cascade remain unknown in almost 50% of aHUS patients [16,17]. The specific complement gene mutation was not identified in the patient.

Historically, the clinical outcomes of aHUS have been unfavorable with up to 25% of patients dying during the acute phase and up to 50% of survivors progressing to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1]. The outcomes are likely to improve thanks to humanized monoclonal antibody eculizumab that blocks C5 cleavage and the formation of the pro-thrombotic, pro-inflammatory, lytic and cytotoxic terminal complement products C5a and MAC [18,19]. The patient experienced complete resolution of clinical signs and symptoms associated with TMA of the kidney and had no evidence of chronic kidney disease during 24 months of eculizumab therapy.

At least 20% of patients with primary aHUS experience extra-renal manifestations and approximately 5% of patients develop life-threatening multivisceral failure [5,20]. HUS may present with ischemic colitis and may be misdiagnosed as acute appendicitis or acute UC [21,22]. The present case is unique in that the patient developed aHUS in the course of chronic active UC. Hyperactivity of the alternative complement cascade plays a role in the pathogenesis of IBD, including UC [23-26]. It is still unclear whether deposition of C3a, C5a or MAC is responsible for inflammation in the intestinal mucosa in all IBD patients or only in a selected group. We were unable to demonstrate deposition of MAC using paraffin-embedded rectal tissue obtained during the UC flare 3 months before the diagnosis of aHUS. This procedure is less sensitive than immunostaining on frozen tissue and the negative findings in the colon may represent false negatives due to the low sensitivity for small amounts of deposit. Improvement of gastrointestinal manifestations after starting eculizumab in the patient who previously suffered severe gastrointestinal symptoms suggests the role of alternative complement pathway in the intestinal inflammation.

Similar to genetically mediated C5 deficiency, functional C5 deficiency created by eculizumab increases the risk of Neisseria meningitidis infection [18]. At the time of presentation, available vaccines did not cover all Neisseria meningitidis strains, including the most prevalent in the US serotype B. The two cases of meningococcal sepsis reported during eculizumab exposure occurred in immunized patients who were not receiving antibiotic prophylaxis [27]. The patient has continued antibiotic prophylaxis for Neisseria meningitidis without experiencing infectious complications 24 months after the initiation of therapy.

Deposition of C3 and MAC in the endothelium can predict complement activation in aHUS [28]. While circulating C3 levels are decreased in 30-50% of aHUS patients [1,29], the levels do not correlate with the disease activity or the clinical response to eculizumab [28]. This is illustrated by the fluctuating C3 levels in the patient (Fig. 2). Specific and sensitive markers of complement activation in aHUS are lacking and such markers are needed for the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation and for monitoring the C5 blockade in response to eculizumab.

3. CONCLUSION

Dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway may not only manifest in the kidney but other organs may be involved as well. As illustrated by this case, there is no correlation between C3 levels and disease activity in aHUS, but resolution of clinical symptoms is important to establish effectiveness of therapy. Biomarkers of complement activation in aHUS are needed for the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation and for monitoring the C5 blockade in response to eculizumab.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LDH

lactate dehydrohenase

- ESR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- C

complement protein

- PNH

paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- ADAMTS

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif

- APC

activated Protein C

- MTHFR

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

- ANA

anti-nuclear antibody

- ANCA

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- ASO

anti-streptolysin O; methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

- LAC

lupus anticoagulant

- vWD

vonWillebrand factor

- CF

complement factor

- dsDNA

double stranded DNA

- MPLA

multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification testing

- MCP

membrane cofactor protein

- TCC

terminal complement complex; Normal values are in parenthesis

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Authors TNW and HG wrote the draft of the manuscript. Author ASU managed the literature searches. Authors ASU, TNW and RJ designed the figures, managed literature searches and contributed to the correction of the draft. Author ASU provided the case, the figures and supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONSENT

All authors declare that written informed consent was obtained from the patient (or other approved parties) for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

It is not applicable.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loirat C, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;(6):60. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romagnuolo J, Fedorak RN, Dias VC, Bamforth F, Teltscher M. Hyperhomocysteinemia and inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence and predictors in a cross-sectional study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):2143–2149. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang Y, Xia X, Wang W, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia and related genetic polymorphisms correlate with ulcerative colitis in Chinese Han population in Central China [corrected]. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012;62(1):203–210. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loomis LJ, Aronson AJ, Rudinsky R, Spargo BH. Hemolytic uremic syndrome following bone marrow transplantation: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;14(4):324–328. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(89)80214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komeno Y, Ogawa S, Ishida T, et al. Ischemic colitis as a manifestation of thrombotic microangiopathy following bone marrow transplantation. Intern Med. 2003;42(12):1228–1232. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lansigan F, Isufi I, Tagoe CE. Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia resembling thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in systemic lupus erythematosus: the role of ADAMTS13. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(5):824–829. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skerka C, Licht C, Mengel M, et al. Autoimmune forms of thrombotic microangiopathy and membrano-proliferative glomerulonephritis: Indications for a disease spectrum and common pathogenic principles. Mol Immunol. 2009;46(14):2801–2807. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganesan C, Maynard SE. Acute kidney injury in pregnancy: The thrombotic microangiopathies. J Nephrol. 2011;24(5):554–563. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.6250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geraghty MT, Perlman EJ, Martin LS, et al. Cobalamin C defect associated with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1992;120(6):934–937. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81967-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Hove JL, Van Damme-Lombaerts R, Grunewald S, et al. Cobalamin disorder Cbl-C presenting with late-onset thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111(2):195–201. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delvaeye M, Noris M, De Vriese A, et al. Thrombomodulin mutations in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):345–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemaire M, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Schaefer F, et al. Recessive mutations in DGKE cause atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Nat Genet. 2013;45(5):531–536. doi: 10.1038/ng.2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemp EJ, Strain L, Diaz-Torres ML, Goodship JA, Goodship TH. The development of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome is not influenced by thrombophilia susceptibility factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(9):2128–2130. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danese S, Sgambato A, Papa A, et al. Homocysteine triggers mucosal microvascular activation in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):886–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Guldener C. Why is homocysteine elevated in renal failure and what can be expected from homocysteine-lowering? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(5):1161–1166. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noris M, Remuzzi G. Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(17):1676–1687. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noris M, Mescia F, Remuzzi G. STECHUS, atypical HUS and TTP are all diseases of complement activation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(11):622–633. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuber J, Fakhouri F, Roumenina LT, Loirat C, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, French Study Group for a HCG Use of eculizumab for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(11):643–657. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169–2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Fakhouri F, Roumenina L, Dragon-Durey MA, Loirat C. [Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome related to abnormalities within the complement system]. Rev Med Interne. 2011;32(4):232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craner GE, Burdick GE. Acute colitis resembling ulcerative colitis in the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Am J Dig Dis. 1976;21(1):74–76. doi: 10.1007/BF01074143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dillard RP. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome mimicking ulcerative colitis. Lack of early diagnostic laboratory findings. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1983;22(1):66–67. doi: 10.1177/000992288302200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johswich K, Martin M, Bleich A, et al. Role of the C5a receptor (C5aR) in acute and chronic dextran sulfate-induced models of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(12):1812–1823. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugihara T, Kobori A, Imaeda H, et al. The increased mucosal mRNA expressions of complement C3 and interleukin-17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160(3):386–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu F, Fernandes SM, Davis AE. The role of the complement and contact systems in the dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model: the effect of C1 inhibitor in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298(6):G878–883. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00400.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain U, Woodruff TM, Stadnyk AW. The C5a receptor antagonist PMX205 ameliorates experimentally induced colitis associated with increased IL-4 and IL-10. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168(2):488–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillmen P, Muus P, Roth A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of sustained eculizumab treatment in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(1):62–73. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noris M, Galbusera M, Gastoldi S, et al. Dynamics of complement activation in atypical HUS and how to monitor eculizumab therapy. Blood. 2014 doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-558296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noris M, Caprioli J, Bresin E, et al. Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1844–1859. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02210310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]