Abstract

Purpose

To provide recommendations and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital preparations for an influenza pandemic or mass disaster with a specific focus on enhancing coordination and collaboration between the ICU and other key stakeholders.

Methods

Based on a literature review and expert opinion, a Delphi process was used to define the essential topics including coordination and collaboration.

Results

Key recommendations include: (1) establish an Incident Management System with Emergency Executive Control Groups at facility, local, regional/state or national levels to exercise authority and direction over resource use and communications; (2) develop a system of communication, coordination and collaboration between the ICU and key interface departments within the hospital; (3) identify key functions or processes requiring coordination and collaboration, the most important of these being manpower and resources utilization (surge capacity) and re-allocation of personnel, equipment and physical space; (4) develop processes to allow smooth inter-departmental patient transfers; (5) creating systems and guidelines is not sufficient, it is important to: (a) identify the roles and responsibilities of key individuals necessary for the implementation of the guidelines; (b) ensure that these individuals are adequately trained and prepared to perform their roles; (c) ensure adequate equipment to allow key coordination and collaboration activities; (d) ensure an adequate physical environment to allow staff to properly implement guidelines; (6) trigger events for determining a crisis should be defined.

Conclusions

Judicious planning and adoption of protocols for coordination and collaboration with interface units are necessary to optimize outcomes during a pandemic.

Keywords: Coordination and collaboration, Recommendations, Standard operating procedures, Intensive care unit, Hospital, H1N1, Influenza epidemic, Pandemic, Disaster

Introduction

Natural and man-made disasters as well as outbreaks of infectious diseases are capable of producing a mass casualty event (MCE) that has the potential to generate large numbers of critically ill patients sufficient to overwhelm hospital and critical care resources. In a MCE, the health care system, individual hospitals and the intensive care units (ICUs) within them should function as a single integrated system to maximize their effectiveness. From an ICU perspective, it is necessary to be capable of good interpersonal communication as well as good intra-departmental coordination and collaboration [1]. It is therefore important to have in place systems and processes to ensure good systematic internal hospital coordination and collaboration. To this end an effective crisis plan should be formulated prior to the MCE, implemented when it occurs and be updated as the event evolves [2]. While situational knowledge is key to the preparation of detailed systems and collaboration plans, there are general principles that may assist in the development of local systems and processes. The operating procedures described below are the result of previous experience with MCEs and adapted recommendations from previously published documents.

Purpose

To ensure that during a crisis, ICUs in a hospital are capable of effectively collaborating with other hospital units, the overall hospital coordinating structure and regional ICU resource committees to ensure the best possible patient care and outcome.

Scope

This standard operating procedure (SOP) primarily focuses on facilitating cooperation between the ICU services (including the nurses working within the ICU) and other key departments within hospitals during a MCE. The other key departments include:

Other clinical departments or divisions (e.g., internal medicine, infectious diseases and microbiology, anesthesiology, surgery, operating rooms and emergency department).

If nursing administrative and operational structures are independent, an interface with nurses, both within the ICU and within other departments.

Hospital administration (including equipment, pharmaceuticals and medical supplies).

Laboratory services.

Supporting health services (e.g., radiology, microbiology, physiotherapy).

Hospitals should implement this SOP within the broader network of cooperation at a local, regional/state and national level. In particular, ICU resources are frequently limited and vary in quantity and complexity from hospital to hospital. Therefore, a direct coordination interface with a relevant regional ICU resource body or authority, such as a Regional Emergency Executive Control Group, is recommended to share information regarding availability of vital equipment, manpower and pharmaceuticals.

While recognizing the need for close cooperation with out-of-hospital medical services, the affected community and public at large, this SOP is restricted primarily to intra-hospital cooperation and coordination.

Goals and objectives

To establish a system of communication, coordination and collaboration between the ICU and key departments and units by:

- Identifying departments, units and structures (stake-holders) that are likely to interface with the ICU under conditions of MCEs. Identified key interfaces with the ICU include:

- nurses, if functioning under independent administrative and operational structures;

- emergency department;

- operating rooms—stop or dramatically decrease elective surgery;

- hospital operations center (hospital management and administration);

- hospital wards under relevant clinical departments;

- pharmacy;

- laboratories;

- support departments (microbiology, radiology, physiotherapy);

- other ICUs, if functioning under independent administrative and operational structures.

- Identifying the key functions or processes requiring coordination and collaboration under conditions of a MCE. Key functions may include:

- Manpower utilization (surge capacity) and sharing or re-allocation of personnel, e.g., mobilization of under-utilized manpower from operating rooms (during an infectious disease outbreak) to the ICU.

- Equipment utilization and reallocation of equipment, e.g., transfer of operating room and recovery room ventilators to the ICU.

- Physical environment utilization, e.g., reallocation as a result of potential expansion or restriction of ICU services.

- Supply utilization—ensuring the appropriate allocation of pharmaceuticals, disposables, personal protective and other infection control equipment for the high-risk ICU environment.

- Managing patient admission and discharge.

- Identifying the appropriate personnel to function as inter-departmental contacts, e.g., ICU triage officer, infection control officer, emergency department admissions and patient transfer officer, etc.

- Identifying appropriate methods and points of inter-departmental contact, e.g., for ICU admissions, designated ICU triage officer to be contacted by pager/beeper, designated mobile telephone/facsimile (numbers provided), etc.

- Sharing clinical information and illness data, e.g., unified hospital database for disaster patient information and regional databases.

- Managing surge capacity for supporting services—laboratory and microbiological services, radiological services, etc.

- Providing a hospital structure and process to ensure establishment and dissemination of emergency response policies that describe the required department and unit cooperation. Preparation and communication are required to ensure the following:

- Appropriate preparations to ensure cooperation and coordination for known and shared areas by involved parties.

- Coordinated responses by involved parties should ensure maximally effective functioning of critical care services.

- Feedback is obtained to allow existing policies to evolve and improve.

- Demonstration of transparency and accountability.

Defining the roles and responsibilities of key individuals responsible for the implementation of emergency response plans should be defined. These individuals should be properly trained to perform their duties.

Definitions

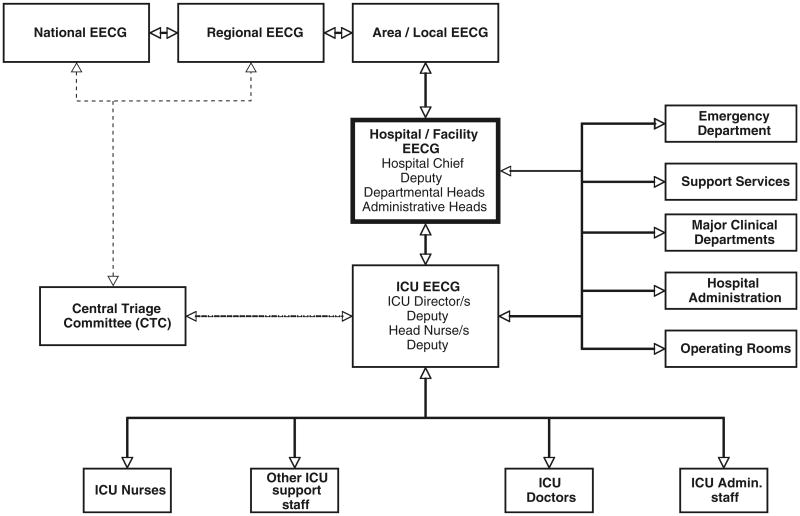

Emergency Executive Control Groups (EECGs): Executive operations centers at key levels within the overall health provision service—from the ICU to the local, regional/state or national EECGs (Figs. 1, 2). The number of EECGs will depend on the size and administrative structure of the individual countries and regions.

Fig. 1.

Schematic algorithm describing key lines of authority (command chain) and information flow (bi-directional) during a MCE/crisis. The Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group (HEECG) is the central operations center with “command and control” responsibility for the overall management of the crisis. It should consist of the Hospital chief, heads of all major clinical and support departments and key supply and logistic divisions. The Hospital EECG should determine whether to open new wards, redeploy staff, suspend or redirect services (e.g., elective operations), prioritize the allocation of hospital supplies (including personal protective equipment), endorse triage policies and formalize infection control policies. The ICU EECG provides the Hospital EECG with information such as ICU functionality, capacity, projected staff and supply requirements, and preferred triage and discharge policies. The ICU EECG ensures that relevant policies agreed upon and endorsed by the HEECG are implemented within the ICU. It is made up of at least the ICU director, a deputy, the head nurse and deputy and one or more triage officers. In the case of multiple ICUs in a hospital under different administrative authorities, each ICU should have an independent ICU EECG. An additional combined ICUEECG may be considered desirable. Other potentially important interfaces are shown

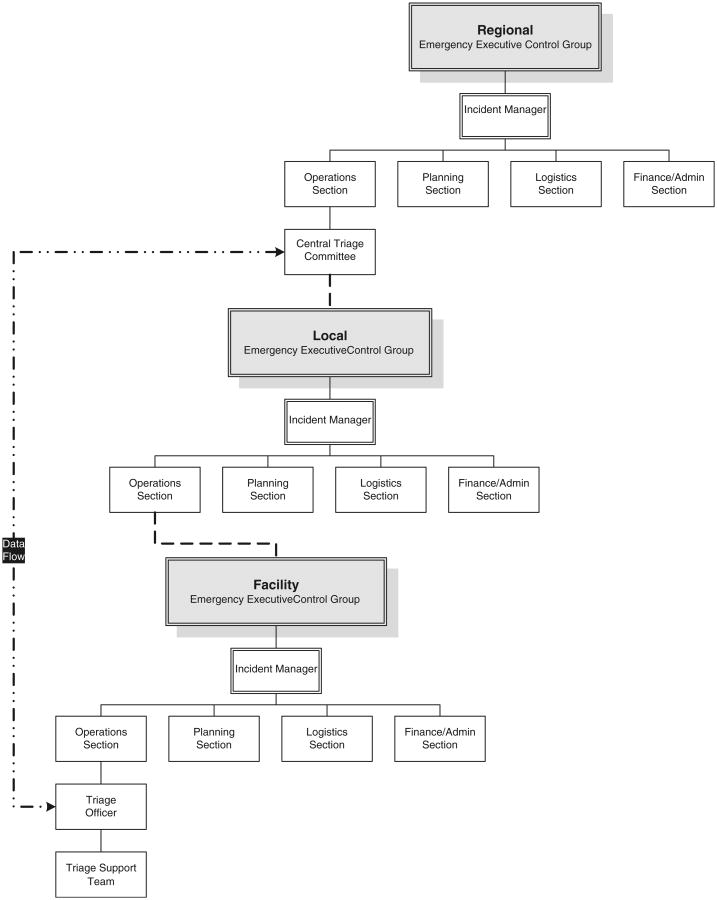

Fig. 2.

Coordination with interface units: dashed lines indicate the continuity of the lines of authority for triage from the Central Triage Committee (CTC) down through the incident management system (IMS) levels. Two-way communication should flow through this chain. This is not meant to indicate lines of command and control. The dashed and dotted line indicates the direct data inputs that should flow between (bi-directional) the local triage officer and the CTC

ICU Emergency Executive Control Group (ICUEECG): An ICU operations center with executive responsibility for the overall management of the crisis within the ICU. This group or its representative should have direct access to the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group.

Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group (HEECG): A central hospital operations center with executive responsibility for the overall management of the crisis within the hospital. This group or its representative should have direct access to the Regional Emergency Executive Control Group.

Local Emergency Executive Control Group: A local area operations center with executive responsibility to liaise with and facilitate the flow of information between hospitals in the area and to link with regional health structures. It should also coordinate the provision of scarce resources among health facilities within their area.

Regional Emergency Executive Control Group: A regional/state (depending on the size of the region concerned) operations center with executive responsibility to liaise with and facilitate flow of information and resources between area hospital groups within the region and link them with other regional/national health structures.

Situational awareness: Being aware of what is happening in the environment, and understanding how information, events and one's own actions will impact on goals and objectives in both the present and the near future.

Stakeholders: Those parties with a direct interest in matters of cooperation and collaboration with the ICU during a MCE.

Triage officer: An intensivist or other physician with appropriate critical care experience who applies the triage protocol to decide the disposition of critically ill and injured patients during a MCE.

Incident Management System (IMS): employs standardized processes, protocols and procedures that all responders use to coordinate and conduct response actions. It includes a standard organizational structure with five functional areas—command, operations, planning, logistics and finance/administration [3]. The IMS structure contains Emergency Executive Control Groups at the facility, local, regional/state or national levels (Fig. 2) (see Chap. 7, Critical care triage).

Incident manager: implements the IMS at the facility, local, regional/state or national levels.

Central Triage Committee (CTC): The experts at the regional level within the operations arm of the IMS with local, regional and/or national situational awareness who interact with hospital triage officers, incident managers or the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Groups locally or the Regional Emergency Executive Control Group (Figs. 1, 2) (see Chap. 7, Critical care triage).

Phases of a MCE: The phases of a MCEs may be divided into sequential phases with distinct characteristics—pre-crisis (corresponding to phase 1–3 of the WHO pandemic phase descriptions and main actions by phase), MCE/crisis phase (corresponding to WHO phases 4, 5 and 6), post-peak phase (corresponding to the WHO post-peak phase) and post-MCE/crisis phase (corresponding to the WHO post-pandemic phase) [2].

Basic assumptions

The hospital has or should establish a Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group with executive “command and control” responsibility, made up of senior representatives from all major stakeholders to manage and coordinate the resources available within the hospital.

Cooperation and coordination between the hospital and the local, regional/state, national or international levels occurs and should primarily be conducted through and by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group.

The communication interface with the community and public should be initiated and guided by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group. Information relating directly to the ICU should be provided to the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group by the ICU Emergency Executive Control Group or directors. The ICU should only communicate directly with the public on occasions that are considered by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group to be in the public interest.

A Central ICU Resource Group exists to advise the ICU triage officer within the hospital on local, regional/state or national coordination of surge policy and resource distribution. It is also assumed that the appointed ICU triage officers act for and under the guidance of the ICU Emergency Executive Control Group within the hospital using accepted triage decision-making processes [4, 5].

The transport of critically ill patients is dealt with by standard clinical protocols.

Lines of authority

Local situational awareness is fundamental to identify specific requirements for cooperation and coordination of hospital resources. The Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group is best positioned to identify key areas of interface, make appropriate policy decisions and implement guidelines and policies. The Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group should be established in pre-crisis conditions and be given the authority for assuming relevant command and control functions within the hospital once a crisis is declared. Bi-directional flow of information should follow this communication and command chain. A schematic of proposed lines of authority is shown in Fig. 1.

Trigger events for determining a MCE or crisis should be defined (Table 1) [2, 6]. The hospital chief executive or equivalent should be responsible for determining the presence of a MCE or crisis and authorizing appropriate responses.

Table 1. Examples of conditions required to initiate a MCE, adapted from references [2, 6].

| Declared state of emergency or a regional incident of national significance |

| Initiation of national disaster medical system, or national aid mechanism or national resource management system |

| Surge capacity is fully employed within local or regional hospitals |

| The identification of a critically limited ICU bed situation, likely to be severely exacerbated by a known or imminently expected MCE |

| A request for resources and infrastructure needs to be made to area and regional health officials |

The ICU Emergency Executive Control Group uniquely possesses situational awareness relating to ICU current functional capacity, resource needs, expansion capacity and interface needs. Therefore, communication between the ICU Emergency Executive Control Group and the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group is crucial. It is recommended that this function be undertaken by the ICU Director and/or direct deputy.

In the case of multiple ICUs in a hospital, each under different administrative authorities, each ICU should have an independent ICU Emergency Executive Control Group, but an additional combined ICU Emergency Executive Control Group may be desirable.

Concepts of operations (see Chap. 7, Critical care triage)

Pre-crisis phase

The pre-crisis period exists before mass casualties have occurred or can be imminently predicted to occur. The duration of this period is usually long and uneventful, but as the onset of a MCE is unpredictable, the “peaceful period” remains critically important as it provides the opportunity to develop systems to ensure eventual cooperation and coordination during a MCE. During the pre-crisis phase, the framework, systems and processes required to ensure a coordinated response are put in place. Relevant Emergency Executive Control Groups are formed and meetings held. Within the hospital, the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group forms the primary coordinating center (Fig. 1).

Documents describing interface procedures and policies should be produced using a standard procedure (Table 2). As part of standard procedure, all members of the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group should formally review relevant documents ensuring cross-department acceptability. In addition, the internal MCE documents of individual hospital departments should be reviewed to ensure that Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group members understand the internal requirements of other stakeholders and that incompatibilities and conflicts are systematically resolved at a central level (Table 3). Documents should be produced by each hospital department independently. Documents should be written in sufficient detail to provide procedural clarity. Contact points, contact methods, designated officers, precise responsibilities and limits of authority should be described in detail. Not only should operational guidelines be developed, but the availability of sufficient equipment should be ensured, and an adequate physical environment to allow staff to properly implement the guidelines and function optimally should be provided.

Table 2. Overview of procedures for document production and control.

| Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group designates individual or group to produce draft document |

| Draft document circulated and reviewed by Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group |

| Final document cleared for dissemination by Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group |

| There should be a method to track and keep a record of all documents approved and disseminated by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group |

| The Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group should be informed of any delays in dissemination |

Table 3. A proposed list of key policy documents required to ensure successful coordination during a MCE.

| Reprioritization of resources |

| Manpower utilization (surge capacity) and sharing or re-allocation of personnel |

| Equipment utilization—re-allocation of equipment |

| Physical environment—re-allocation as a result of potential expansion or restriction of ICU services |

| Equipment, pharmaceuticals and supply utilization |

| Changes in patient admission and discharge policies |

| Policy for liaison with outside institutions for patients coming in and for patients going out of the ICU or hospital |

| Clinical and administrative cooperation |

| Sharing of clinical information |

| Designating the appropriate personnel for inter-departmental contacts |

| Supporting services—protocols for dealing with surge capacity for laboratory services, radiological services, hospital supplies, etc. |

| Data collection and quality assurance |

| Sharing of illness data and research |

| Formal or informal feedback gathering mechanisms—named or anonymous web-based reporting, suggestion boxes, debriefing sessions, etc. |

An ICU Emergency Executive Control Group is formed to produce internal ICU policy documents interrelating to departmental functions covering the same interface areas to be discussed and coordinated at the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group (Table 3). Documents relating to current functional capacity, surge resource needs and expansion capacity are integrated with the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group.

Although many inter-departmental contacts will occur and be guided by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group, it is necessary for the ICU Emergency Executive Control Group to appoint designated ICU officers to facilitate day-to-day responses and act as points of contact required in policy documents and implementation for the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group. Examples may include the appointment of frontline admission and discharge (triage) officers, a radiology ICU contact officer, nurse liaison officers, infection control officer, pharmacy officer, public relations officer, etc. Up to date and accurate information, including names, designations and contact numbers, are required. A master list of relevant designations and contact details is recommended.

All relevant formulated and agreed upon policies should be disseminated to frontline staff throughout the hospital for formal and informal feedback by an appropriate method (Table 4). Frontline staff throughout the hospital should also be made aware of designated officer appointments. Designated officers should be fully aware of their roles and responsibilities.

Table 4. Technology for ensuring communication channels during a MCE.

| Communication technology | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Traditional fixed telecommunication lines | Robust in times of high system usage |

| Mobile telecommunication systems | Commercial networks may be overwhelmed when surge capacity exceeded. Consider internal networks |

| Paging systems | Robust, but lack privacy |

| Individual paging (beeper) systems | Robust, limited information transfer |

| Intranet sites | High security, reduced accessibility, 24-h access |

| Internet sites | High accessibility, reduced security, 24-h access |

| Fax | Robust, mass faxing possible by preprogramming contact number data sets |

| Hand-held radio transmitter/receivers | Robust in times of surge mobile phone usage |

| Printed material | Noticeboards, leaflets, etc. |

| Direct verbal communication | Group or personal briefings |

All Emergency Executive Control Group members, senior administrators and acute care hospital staff should receive training in communications (Table 5).

Table 5. Desirable competencies for good quality crisis communication.

| Ability to execute defined communication plan |

| Communicate in a timely manner |

| Demonstrate competence and expertise in communication techniques |

| Exhibit honesty and transparency |

| Demonstrate personal communication skills |

| Utilize a feedback mechanisms to improve competence |

Each region should establish an Incident Management System with Emergency Executive Control Groups at facility, local, regional/state or national levels to exercise authority and direction over resources. Each IMS includes five functional areas—command, operations, planning, logistics and finance/administration (Fig. 2). Within the regional IMS is a CTC of experts with broad situational awareness, capacity to develop and modify protocols, monitor outcome and coordinate responses. Cooperation and communication between various levels is essential [6].

Clinicians should join regional databases with a common global registry of ICU H1N1 patients to gain important, timely information for treating severe H1N1 cases [7]. Information can help to evaluate triage decisions and provide data to areas not yet affected by a pandemic. Randomized controlled trials testing treatment strategies should be expedited with rapid Investigational Review Board approvals [7, 8].

MCE or crisis phase

During the crisis phase the actual or imminently expected number of patients admitted is in excess of surge capacity. The MCE/crisis activation should be triggered when it is evident that resource shortfalls are or will occur across a broad geographic area based upon current or predicted demands, despite all reasonable efforts to extend resources or obtain additional resources. Although the MCE/crisis activation can be triggered by a hospital chief executive (or equivalent) or any of the Emergency Executive Control Groups, the activation will usually occur by Regional or National Emergency Executive Control Groups or high-ranking governmental officials. After the activation of the MCE/crisis, all Emergency Executive Control Groups are activated and appropriate policies and guidelines implemented.

The Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group should meet at least once or twice daily, depending on circumstances, to review the overall management of the MCE. The meeting should include an overall situation report from the hospital chief executive and reports from all members representing key interface units. Situation reports should include information such as: numbers and condition of patients admitted since the previous meeting, numbers currently being treated, bed status in various departments and wards, anticipated resource needs, short-and long-term functional and capacity expectations and staff functionality status. Other problems of possible concern to interface units should be discussed on an ad hoc basis. The hospital chief executive's daily report to the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group should also include relevant information from the Local and Regional Emergency Executive Control Groups. All key policy areas (Table 3) should be reviewed daily. Feedback gathered from formal and informal sources should be reported and steps taken to rectify identified problems. Rectified or new policy documents produced should undergo the standardized clearance process (Table 2), which may be expedited or modified as required in the initial phase to ensure rapid promulgation.

Regular situation report summaries and new policies and procedures should be disseminated to frontline staff in an appropriate manner, ideally by a combination of methods—group briefings, placement on intranet-/Internet-based sites or information boards, through leaflets, etc. While an essential communication infrastructure should be maintained by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group, senior members of the HEECG who represent individual departments or units remain ultimately responsible for communication and implementation at the front line.

The ICUEECG should meet at once or twice daily and continue to manage internal policy documents and remain responsible for ICU function. It should provide the interface between the ICU administration, the ICU frontline workers and the HEECG. In addition, regular direct contact with the Central Triage Committee and the Local Emergency Executive Control Group should be maintained and communicated to the HEECG.

Post-peak phase

During the post-peak phase, the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group should usually meet daily (or less frequently if required). The ICUEECG may similarly meet less frequently. Operationally, the functions remain the same as in the MCE/crisis phase; however, activity will typically be less intense.

Post-MCE/crisis phase

The Emergency Executive Control Group's functions remain similar, and the frequency and duration of meetings can be appropriately reduced. It is important to remain vigilant for any signs of recurrence or deterioration of the MCE condition and to maintain operational standards.

Formal assessment of all aspects of the hospital's performance and ability to coordinate their response to the MCE should be undertaken as soon as feasible (ideally within 3–6 months) by external and internal review. The review should be undertaken by formally constituted internal and at least one independent external committee. The function of the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group and its components should be open to scrutiny, and minutes and other records, documents and policies should be reviewed. Staff at all levels should be formally interviewed by the appropriate review committee to identify gaps in performance, response competence and policies that may be improved for future responses.

Functional roles and responsibilities of the internal personnel and interface agencies or sectors

Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group (HEECG): Members should include the Hospital Chief Executive (or equivalent) and deputy, the heads of relevant administrative departments such as supply, engineering, maintenance, etc., head or deputy from the ICU, emergency departments, medical and surgical departments, nursing departments (e.g., head nurse of the hospital, ICU head nurse, head nurse of other critical areas such as the emergency room, etc.), operating rooms, hospital wards, laboratories, and if necessary other support departments such as physiotherapy or occupational therapy. Its primary role is to manage and coordinate all internal hospital functions and departmental interfaces. The HEECG may appoint sub-committees as appropriate to deal with specific issues. The HEECG should make such decisions as determining whether to open new wards, whether to reallocate staff from one department to another, determine which hospital functions will be suspended or redirected (e.g., suspension of elective operations and reallocation of operating room staff), prioritize the allocation of hospital supplies (including personal protective equipment), determine hospital visiting policy, endorse triage policies of individual departments, formalize infection control and isolation policies and formulate discharge policies.

ICU Emergency Executive Control Group (ICUEECG): Members should include at least the ICU Director, a deputy, the head nurse and deputy and one or more triage officers. This group or its senior representatives should have direct access to the HEECG and provide it with information on ICU functionality, capacity, projected staff and supply requirements, preferred triage and discharge policies, etc. The ICUEECG should ensure that relevant policies agreed upon and endorsed by the HEECG are implemented within the ICU. In addition to providing the interface with the HEECG for policies with hospital wide implications, it is also responsible for determining internal ICU policy and for coordinating direct interface with other ICUs and clinical departments and support departments. The ICUEECG as the HEECG also interfaces with the Central Triage Committee through the triage officer/s and external institutions seeking ICU support for patients.

A representative with some training in public communication during crises should be nominated from the HEECG and/or ICUEECG to deal with public media enquiries relating to the ICU that directly concern the public interest. The communication representative should have some awareness of the requirements for public media communication. A Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication resource is provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [9].

Local Emergency Executive Control Group (LEECG): Composition may vary from country to country and area to area, but members may include: a senior health authority administrative officer representing the area, a health authority risk manager, health authority public relations manager, representatives of other health facilities such as private clinics, old age homes, public health facilities and the chief executive officers or deputy of all hospitals in the geographic area (such as a city). The LEECG should liaise with and facilitate flow of information between local area hospitals and link with regional health structures including the Regional and/or National Emergency Executive Control Groups. It should also coordinate responses among health facilities within their locality. Coordination with the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group and the Local, Regional or National Emergency Executive Control Groups is demonstrated in Fig. 2 (see Chap. 7, Critical care triage).

Regional or National Emergency Executive Control Groups: Composition may vary but members may include: a senior health authority administrative officer, administrative officers representing the individual areas, a regional or national health authority risk manager, public relations manager, representatives of other health facilities in the region or country such as private clinics, old age homes and public health facilities. A regional or national operations center with executive responsibility should liaise with and facilitate the flow of information between local hospital groups within the region and link them with regional and national health structures.

Central Triage Committee: This regional level committee should have a mandate to develop triage protocols, train triage officers, help determine if MCE/crisis activation of triage should be instituted during an MCE, monitor triage outcomes, monitor the MCE and advise on regional distribution or re-distribution of ICU resources, refine triage protocols and determine when to cease MCE/crisis triage.

Logistics support and requirements necessary for the effective implementation of the SOP

Designated rooms sufficiently large for group meetings and with sufficient audiovisual technology and secretarial support. It is recommended that there be records, in writing, of all Emergency Executive Control Group Meetings.

Appropriate information technology (IT) and communication facilities sufficiently robust to function under surge conditions with backup systems available (Table 4). Communications systems should provide for immediate individual member contact, using methods such as such as individual pagers, mobile and fixed line telephone numbers.

All members of executive groups, departmental heads or deputies and designated interface officers should be contactable 24 h per day, 7 days a week. An up to date master list of all relevant members and officers, with contact details, should be maintained by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group. A corresponding front line master list of interface officers should be available in all clinical areas.

There should be established methods of dissemination of information to frontline staff, e.g., websites (intranet, Internet), an e-mail distribution network, scheduled briefing sessions, designated information boards, etc. (Table 4).

Required communication technology should be purchased and robustness and reliability tested during full-scale exercises in the pre-crisis period. Attempts should also be made to anticipate possible solutions for telecommunication system overloading during surge periods.

Maintenance of standard operating procedure

It is recommended that hospitals, led by the Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group, should participate in and evaluate full-scale exercises and reviews on a regular basis. Similarly, the regional and national groups should participate in and evaluate, regular full-scale exercises in conjunction with at least two health facilities on each occasion. The ideal frequency of simulations and exercises of this nature is unknown, and the cost and inconvenience of holding large, full-scale exercises should be balanced against likely benefit of improved preparedness. In most cases annual exercises are likely to be sufficient. When appropriate, small-scale paper exercises can be used to supplement full-scale exercises. The exercise should be designed to help identify and assess gaps in preparedness and response competencies in key individuals and units. An evaluation process should occur immediately after each exercise by internal and external evaluators. The SOPs should be modified and updated following each review to ensure that communication technology, processes, protocols and the information contained within them are current.

Recommended training and exercise activities

Current evidence supporting the effectiveness of disaster training is not definitive [10, 11]. It is, however, recommended that all hospitals that provide ICU services should provide training in communication for senior staff in crisis situations. Training should be standardized across the region and tailored to local conditions. Training programs should include the components outlined in Table 5. Training modules to be completed in the pre-event period should be developed.

General communication training regarding communication, coordination and cooperation competency during MCEs should be part of in the standard emergency training provided to all hospital ICU clinical staff as well as interface units [12]. Required communication technology should be purchased and robustness and reliability tested during full-scale exercises. Routine exercises to ensure staff familiarity with policies and procedures throughout the hospital should occur regularly (Tables 5, 6).

Table 6. Scenario planning chart (example).

| Scenario | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country/community status No known Avian influenza case in country. Known cases in another country | ||

| Hospital status No known or suspected cases in hospital | ||

| Hospital personal protective equipment (PPE) status Not currently utilizing routine PPE | ||

| Situation Emergency Department (ED) has admitted a highly suspicious patient with a highly suggestive travel and exposure history. The patient has respiratory failure requiring tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Followed by ICU admission | ||

|

| ||

| Period | Action location | Action summary |

| Pre-event checklist | ICU internal | 1. Updated communication and coordination policies |

| 2. Internal infection control policy | ||

| ICU and ICT | 1. Updated infection control policies | |

| 2. Identified isolation areas | ||

| 3. Training and competence of staff in PPE | ||

| 4. Adequate stockpile of PPE | ||

| Hospital logistics | 1. Stock adequacy of PPE—specify type and quantity | |

| 2. Activation procedure—contact methods and numbers, 24-h system function | ||

| 3. Re-supply procedure | ||

| Medical department | 1. Updated roster of staff for emergency activation | |

| 2. Morale—internal communication procedures | ||

| Nursing department | 3. Staff insurance arrangements | |

| 4. Prophylaxis policies, e.g., anti-viral agents, vaccinations | ||

| Pharmacy | 1. Medication for patients | |

| 2. Prophylaxis for staff, e.g., anti-viral agents, vaccinations | ||

| Housekeeping | 1. Activation of specific infection control housekeeping policies (disposal of used linen, uniforms, PPE, etc.) | |

| Security | 1. Hospital security policy | |

| 2. Public protection policy | ||

| Patient in emergency department (ED) | ED | 1. Activation Procedures |

| HEECG | 1.1 HEECG—all key personnel including Hospital Chief | |

| ICU | 1.2 ICUEECG—all key personnel including Director | |

| ICT | 1.3 Infection Control Team | |

| 2. Transport coordination policies | ||

| Transport | ED | 1. Transport to ICU |

| Security | 1.1 Infection control policies for patient, transport staff | |

| ICT | 1.2 Special infection control equipment | |

| ICU | 1.3 Route | |

| 1.4 Security cordon, decontamination along route | ||

| 1.5 Commandeering elevators, corridors, etc. | ||

| Arrival in ICU | ICU internal | 1. ICU |

| Other hospital departments: | 1.1 Identify and activate isolation area | |

| ICT | 1.2 Activate policy to transfer out existing patients if needed | |

| Infectious diseases department (IDD) | 1.3 Activate infection control policy | |

| Security | 1.4 Activate visitor management policy | |

| Pharmacy | 2. Staff deployment policy | |

| Housekeeping | 2.1 Form patient management team—doctors, nurses, etc. | |

| Engineers | 2.2 Activate quarantine policy | |

| Mortuary | 2.3 Activate staff recruitment, rostering policy | |

| 2.4 Staff care morale and communication policy—situation report, contingencies for food, accommodation, prophylaxis, etc. | ||

| 2.5 Notify Housekeeping, allied health support services, laboratory and mortuary services | ||

| 3. Activate standard policy contact with HEECG and other relevant departments | ||

| 4. Activate public relations and media policy | ||

| Post-event | All | 1. Review functional ability of all EECG groups |

| 2. Review effectiveness of relevant policy documents | ||

| 3. Review capability of frontline staff to interpret and implement policy effectively | ||

| 4. Review current nature of policy documents—contact procedures, telephone numbers, etc. | ||

| 5. Activate staff support and debriefing policies | ||

ICU intensive care unit, ICT infection control team, PPE personal protective equipment, HEECG Hospital Emergency Executive Control Group, ICIEECG ICU Emergency Executive Control Group

The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not reflect policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

On behalf of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine's Task Force for Intensive Care Unit Triage during an influenza epidemic or mass disaster.

Contributor Information

Gavin M. Joynt, Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sha Tin, Hong Kong, People's Republic of China

Shi Loo, Department of Anaesthesiology, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore, Singapore.

Bruce L. Taylor, Department of Critical Care, Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust, Portsmouth, UK

Gila Margalit, Department of Emergency Services, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel.

Michael D. Christian, Department of Medicine, Infectious Diseases and Critical Care, Mount Sinai Hospital and University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Christian Sandrock, Intensive Care Unit, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and Infectious Diseases, UC Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA, USA.

Marion Danis, Department of Bioethics, Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Yuval Leoniv, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel.

Charles L. Sprung, Email: charles.sprung@ekmd.huji.ac.il, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Hadassah Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

References

- 1.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, Mitchell PH, Eldrege DH, Oakes D. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1991–1998. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Pandemic Influenza preparedness and response: a WHO guidance document. Geneva Switzerland: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christian MD, Kollek D, Schwartz B. Emergency preparedness: what every healthcare worker needs to know. Can J Emerg Med. 2005;7:330–337. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500014548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Consensus statement on the triage of critically ill patients. JAMA. 1994;271:1200–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devereaux AV, Dichter JR, Christian MD, et al. Definitive care for the critically ill during a disaster: a framework for allocation of scarce resources in mass critical care: from a Task Force for Mass Critical Care summit meeting, January 26–27, 2007, Chicago, IL. Chest. 2008;133:51S–66S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall J on behalf of the InFact Global H1N1 Collaboration. InFact: a global critical care research response to H1N1. Lancet. 2010;375:11–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61792-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook D, Burns K, Finfer S, et al. Clinical research ethics for critically ill patients: a pandemic proposal. Critical Care Med. 2009 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cbaff4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 14 October 2009];Crisis & Emergency Risk Communication. 2009 http://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/index.asp.

- 10.Hsu EB, Jenckes MW, Catlett CL, Robinson KA, Feuerstein C, Cosgrove SE, Green GB, Bass EB. Effectiveness of hospital staff mass-casualty incident training methods: a systematic literature review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19:191–199. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams J, Nocera M, Casteel C. The effectiveness of disaster training for health care workers: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu EB, Thomas TL, Bass EB, Whyne D, Kelen GD, Green GB. Healthcare worker competencies for disaster training. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:19–28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]