Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the predominant primary liver cancer in many countries and is the third most common cause of cancer-related death in the Asia-Pacific region. The incidence of HCC is higher in men and in those over 40 years old. In the Asia-Pacific region, chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections are the main etiological agents; in particular, chronic hepatitis B infection (CHB) is still the major cause in all Asia-Pacific countries except for Japan. Over the past two decades, the incidence of HCC has remained stable in countries in the region except for Singapore and Hong Kong, where the incidence for both sexes is currently decreasing. Chronic hepatitis C infection (CHC) is an important cause of HCC in Japan, representing 70% of HCCs. Over the past several decades, the prevalence of CHC has been increasing in many Asia-Pacific countries, including Australia, New Zealand, and India. Despite advancements in treatment, HCC is still an important health problem because of the associated substantial mortality. An effective surveillance program could offer early diagnosis and hence better treatment options. Antiviral treatment for both CHB and CHC is effective in reducing the incidence of HCC.

Keywords: Carcinoma, hepatocellular, Liver neoplasms, Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a primary malignant neoplasm derived from hepatocytes, accounting for about 80% of all liver cancers. Other types of liver cancers, including intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hepatoblastoma and angiosarcoma, are relatively rare compared to HCC. Therefore, the morbidity of liver cancer can be regarded to be a broadly accurate reflection of HCC incidence.1,2

HCC is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, being the fifth in men and the eighth in women. It accounts for approximately 5.7% of all new cancer cases. Annually, around 1% of all deaths in the world were related to HCC. Therefore HCC is one of the cancers with the highest mortality rates worldwide.3 Liver cancer is a major health problem in developing countries. The highest age adjusted incidence rates (>20 per 100,000) are recorded in East Asia (North and South Korea, China, and Vietnam), and sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for 82% of liver cancer cases worldwide. In particular, 55% of all HCC cases worldwide are reported from China.4 A medium-high incidence rate is found in Southern Europe, whereas low-incidence areas (<5 per 100,000) are found in South and Central America, and the rest of Europe.5

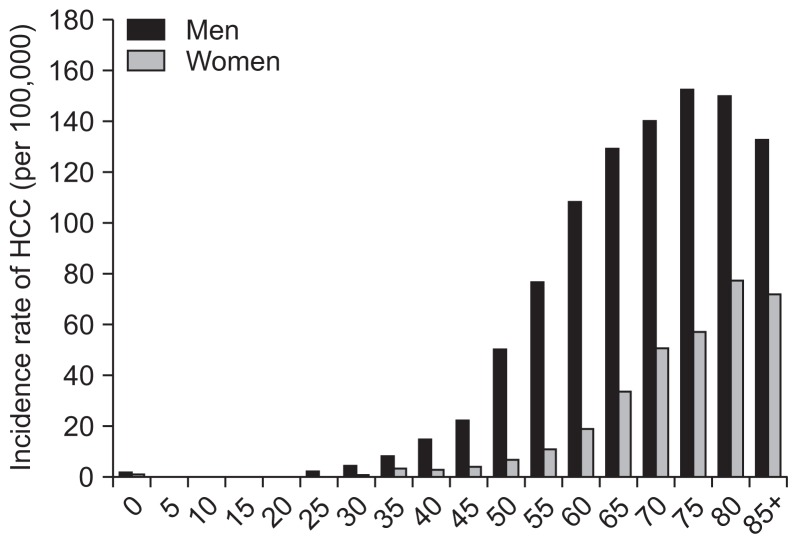

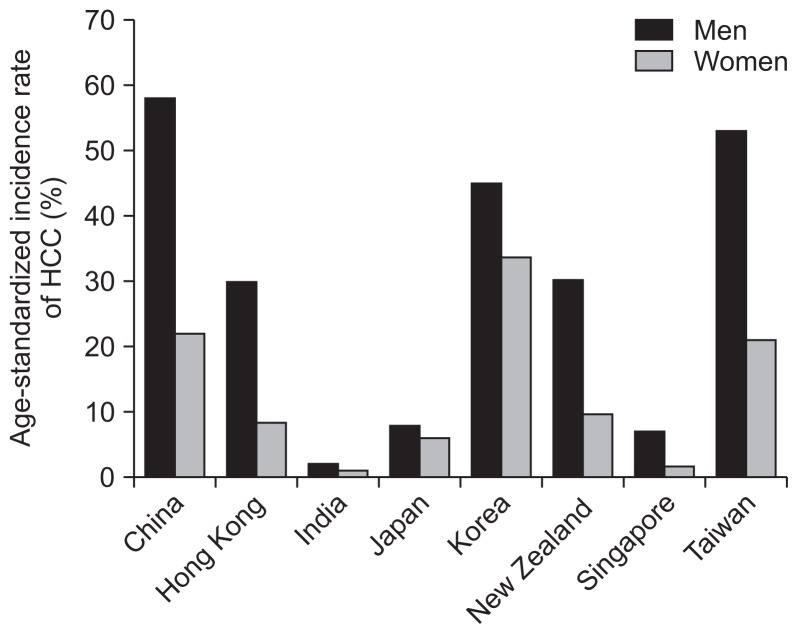

The global age distribution of HCC varies by region, gender, and etiology.6 Globally, the rate of men suffering from HCC is higher than women, with the male to female ratio ranging between 2:1 and 4:1, with the difference being much greater in high-risk areas. In the Asia-Pacific region (especially North and South Korea, Indonesia, and Vietnam), the rate of HCC in men is greater than 4 folds than that of women. In most high-risk Asia-Pacific populations (e.g., Hong Kong), the highest age-specific rates are people aged beyond 75, which is similar to that in the most low-risk Western countries. On the other hand, the age-specific rates of men in high-risk African populations (e.g., Gambia and Mali) tend to peak in the 60 to 65 age group, while that of women peak between 65 and 70 years old. These variations of age-specific patterns are likely related to the differences in the dominant hepatitis virus in the population, the age at viral infection as well as the existence of other risk factors.1,7

RISK FACTORS

Based on available epidemiological data, HCC is a complex disease entity with multiple possible etiologies, and associated with many risk factors and cofactors.8,9 Approximately 70% to 90% of patients with HCC have an available case history of chronic liver disease and liver cirrhosis, with major risk factors including chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).10,11 Additional risk factors for developing HCC include intake of aflatoxin-contaminated food, diabetes, obesity, certain hereditary conditions such as hemochromatosis, and various metabolic disorders.8,10,12

1. Hepatitis B virus

Chronic HBV infection (CHB) has a well-known association with HCC.13 It is estimated that HBV is responsible for 50% to 80% of HCC cases worldwide. Moreover, it is the cause of 75% to 90% of HCC in HBV endemic or hyperendemic regions.14 Globally, 270 million people are infected with CHB, which is almost 5% of the world’s populations; the majority of whom are found in the HCC high-risk regions of Asia-Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa.15 Currently, 75% of CHB carriers are found in Asia. In this region, CHB accounts for 80% of all newly diagnosed HCC. Certain Asia-Pacific countries have a lower HCC incidence, including Singapore, Japan, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.16

1) HBV DNA level

According to a population-based study on the relationship between CHB and HCC, the risk of HCC in patients with high HBV DNA load (>2,000 IU/mL equivalent to 10,000 copies/mL) is much greater than those who have low levels.17,18 The association of high HBV DNA levels with HCC is independent of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positivity, serum alanine amino-transferase levels, and liver cirrhosis.19–22 In the cohort of 3,653 patients who were hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive and anti-HCV negative recruited between 1991 and 1992 in Taiwan, the incidence of HCC increased in proportion to the serum HBV DNA levels, ranging from 108 per 100,000 patient-years for HBV DNA levels of <300 copies/mL to 1,152 per 100,000 patient-years for HBV DNA levels >200,000 IU/mL (1,000,000 copies/mL). Another study demonstrated patients with moderate HBV DNA levels (60 to 2,000 IU/mL), when compared to individuals without HBV infection, also had a higher risk of HCC and liver-related death. Among all other risk factors, serum HBV DNA is the most important viral predictor of HBV-related HCC.17,18

2) Other HBV viral factors

HBV genotype C is closely associated with HCC in patients aged >50 years.23 When compared to genotype B, HBV genotype C has been shown to be an independent risk factor for HCC development.24 More recent data also indicate high serum HB-sAg levels to increase the risk of HCC development, especially among patients with intermediate HBV DNA levels.25,26 Combination of HBV DNA and HBsAg levels could further improve the risk stratification of HCC.

2. Hepatitis C virus

The contribution of HCV infection to HCC varies worldwide. HCV is a major cause of HCC in Western countries and Africa; it also accounts for 80% to 90% of HCC cases in Japan.27,28 HCV infection causes chronic inflammation, proliferation, and cirrhosis of the liver.29 The liver cirrhosis caused by HCV can increase the risk for liver cancer, which was 17-fold higher risk in developing HCC than only than just chronic hepatitis C infection (CHC), although this risk varies and depends on the degree of HCV-related liver fibrosis.30

Coinfections with HBV and HCV may produce a cumulative effect on the development of HCC which varies from additive to synergistic. Thus, globally, the burden of liver cancer attributable to viral infections is likely to be close to 90%.

3. Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is present in about 80% to 90% of HCC and has a prominent role in the development of HCC.31 Unlike in Western countries, where a considerable proportion of cirrhosis are associated with alcoholic liver disease, HBV and HCV remain the most the important cause of cirrhosis in the Asia-Pacific region. However, only around 80% of HBV-related HCC have underlying cirrhosis of the liver, the remaining 20% develop HCC because of the direct oncogenic effect of HBV.

4. Aflatoxin-contaminated food

Aflatoxin B1 is a kind of hepatocarcinogenic mycotoxins which is produced by certain aspergillus species. They can contaminate a large number of traditional foods, including grains, corn, cassava, peanuts, and fermented soy beans, which are produced in the humid areas of Southeast Asia. Aflatoxin B1 can induce DNA mutations, particularly the tumor suppressor p53 gene, resulting in downregulation of p53 in 30% to 60% of all HCCs in these areas.32 In addition, it has been found that individuals with HBV infection and significant intake of aflatoxin have an even higher risk of liver cancer compared with HBV infection alone, suggesting a synergistic effect between HBV and aflatoxin.33

5. Alcohol

Heavy alcohol intake, defined as ingestion of >50 to 70 g/day for prolonged periods, is a well-established HCC risk factor. Although it is reported that alcohol does not have a carcinogenic effect in itself, prolonged alcohol intake can increase the risk of cirrhosis, a major risk factor for HCC. On the other hand, some evidence show that heavy alcohol ingestion can increase the risk of HCC induced by HCV or HBV infection by actively promoting the formation of cirrhosis.34 One study demonstrated that among heavy alcohol drinkers, HCC risk increased in a linear fashion at intake >60 g alcohol on a daily basis and the risk rate was doubled with concomitant HCV infection.30

6. Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is considered to be an important risk factor for both chronic liver disease and HCC possibly by facilitating the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and NASH. Data emerging from epidemiologic studies have shown a longer duration of diabetes to be associated with increased risk of HCC.34,35 A population-based study has reported that diabetes (type 2) is an independent risk factor for HCC, increasing the risk by 2- to 3-fold.36 Similar data is also found in Asia, with a case-control study showing diabetes to increase the risk of HCC.36,37

ASIA-PACIFIC COUNTRIES

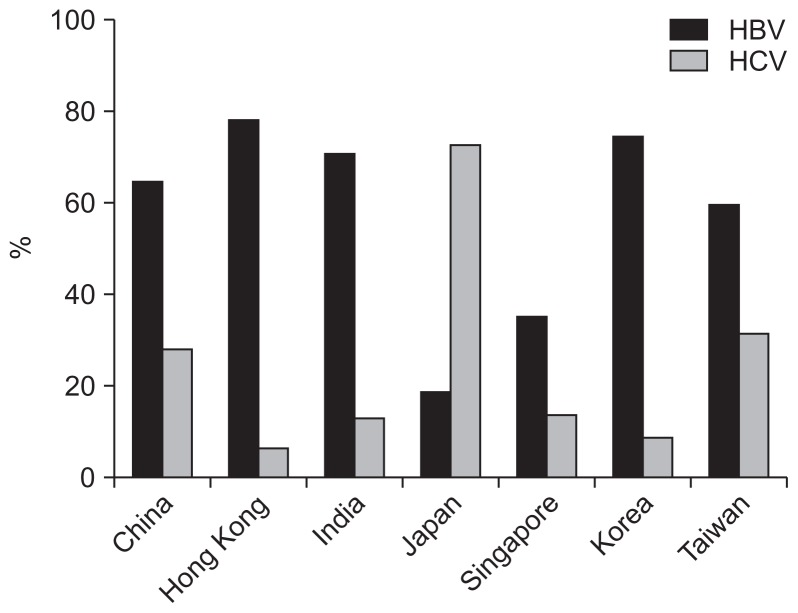

HCC in Asia-Pacific countries has a wide geographic variability. Most of the countries have epidemiological data of HCC in place. These include Australia, China, Hong Kong (Special Administrative Region, China), Singapore, Japan, India, New Zealand, and Taiwan (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The proportions of hepatitis B virus (HBV)- and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma in different Asia-Pacific regions. The data source for each country was as follows: China,44 Hong Kong,50 India,52 Japan,54 Singapore,58 Korea,55 and Taiwan.60

1. Australia

Over the recent decades, the incidence and mortality of HCC in Australia have been gradually increasing. The cause of rising HCC incidence is partly attributed to the mass migration from the Asia-Pacific region,38,39 with the majority of immigrants coming from high-risk HBV endemic countries. Other known risk factors for the increasing incidence of HCC include HBV/HCV coinfection, cirrhosis due to other various causes.

According to an Australian study of HCC incidence as stratified by different chronic liver diseases, the HCC incidence rate of patients with HBV mono-infection was markedly higher than that of those with HCV mono-infection (9.5 vs 6.9 cases per 10,000 person years, p<0.001).40 It is estimated that 50% to 65% of CHB cases in Australia are among people born in Asian countries.41 A recent population-based linkage study showed that Asian-born residents with CHB were 30 times more likely to develop HCC compared with Australian born residents.42 The incidence of HCC with chronic viral hepatitis is associated with increasing age, male gender and other comorbidities. The highest risk of age-specific rates in developing HCC occurs among people aged 75 and older, which is over 14 times the risk of those aged under 45. The risk in male patients is 3-fold higher than that in women. The same phenomena are observed in the HCV-related HCC.40

2. China

Liver cancer is the second most common cancer in China after lung cancer. Overall, the estimated incidence rate of HCC is 40.0 in males and 15.3 in females per 100,000 world standard population. Concerning the annual mortality rate for the five common malignant neoplasms in China, liver cancer ranked as the second cause of cancer mortality in male after lung cancer; while it ranked the third in female after lung and gastric cancer. The mortality rate of liver cancer is higher in males (37.4/100,000) than in females (14.3/100,000).43

In China, some identified risk factors such as HBV, HCV, aflatoxin, alcohol consumption, and tobacco smoking contribute to the incidence and mortality of HCC. Particularly, HBV infection contributes to large number of liver cancer deaths and cases (63.9%), including 65.9% among men and 58.4% among women. For HCV, its rate in liver cancer deaths and cases is lower than that of HBV (27.7% overall; 27.3% in men and 28.6% in women), but is still higher than that of aflatoxin exposure (25% of population), alcohol drinking (15.7%), and tobacco smoking (13.9%).44

Despite the high incidence of liver cancer throughout China, trends of decrease have been observed in some regions. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer and Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, the age-adjusted incidence rate of HCC has been in decline in Shanghai city since 1970s45 and in Tianjin city since 1980s.46,47 In Qidong, a district near Shanghai, the incidence rate has not changed since 1978, except for subjects between age 15 to 34 years, in whom there is a decreasing tendency from 1988 to 2002.48

3. Hong Kong

According to the report from the Hong Kong Cancer Registry 2012 (http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/Statistics.html#cancerfacts),49 liver cancer ranks as the fourth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death. The incidence and mortality of liver cancer is higher in man (fourth and third respectively among all cancers) than that in woman (10th and fourth respectively among all cancers).

In Hong Kong, the incidence of HCC increases with age. As depicted in Fig. 2, the highest age-specific rate occurs among people aged 75 and older, accounting for 152.4 per 100,000 persons. However, over the past 25 years, the incidence of HCC at different age groups (especially age >40 years) has an apparently downward trend, which may be partly explained by the declining rate of HBV infection due to the institution of universal HBV vaccination since 1988. As depicted in Table 1, during the period of 1992 to 2006, CHB is the major cause of HCC in Hong Kong, accounting for 80% cases in 1992 and 78% cases in 2006. From 1992 to 2006, the proportion of HCV-related HCC has increased from 3% to 6.3%.50

Fig. 2.

The incidence rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in both sexes among different age groups in Hong Kong (data from the report of the Hong Kong Cancer Registry, 2012).49 Age-specific incidence rates for liver cancer in 2012.

Table 1.

Etiologies and Demographics of HCC in Hong Kong

| Lai et al. (1981)64 | Lai et al. (1987)65 | Shiu et al. (1990)66 | Leung et al. (1992)67 | Yuen et al. (2000)50 | Cheung et al. (2006)68 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 211 | 186 | 340 | 424 | 306 | 223 |

| HBV, % | - | 75 | - | 80 | 79 | 78 |

| HCV, % | - | - | - | 3 | 4.9 | 6.3 |

| HBV+HCV, % | - | - | - | 3 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| Alcohol, % | - | - | - | - | 5.6 | 5.8 |

| Median age, yr | - | - | - | - | 61 | 63 |

| Male:female | - | 5:1 | - | - | 4:1 | 4:1 |

| Median survival | 3.5 wk | 8–10 wk | 8 wk | - | 11 mo | 11 mo |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

4. India

Based on Cancer Registries in five Indian urban populations (Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, and Bhopal), liver cancer ranks as the fifth most frequent cancer for both genders. Over the period of the last two decades, the observed and estimated age adjusted incidence rates according to different registries have increased, especially in the Mumbai, Chennai, and Bangalore registries. The incidence of HCC is higher in men when compared to women, as illustrated by a study cohort of 213 patients with HCC in 1999–2005 in which 83.1% were male patients.51

In India, HBV infection, HCV infection and alcohol consumption are the main causes of HCC. Based on the above mentioned study cohort, in the 213 HCC patients, HBV positive markers accounted for 150 (70.42%; odds ratio [OR], 48.0%); HCV positive markers accounted for 26 (12.21%; OR, 5.45%); HBV/HCV coinfection was responsible for 10 (4.69%). Heavy alcohol intake was found in 34 (15.96%; OR, 2.83%). A synergistic effect between HCV and alcohol was also found (synergy index, 1.257). There was no evidence of interaction between HBV and alcohol.52

5. Japan

In Japan, HCC ranks as the fourth most common cancer for both genders. Among all cancers in Japan, HCC is the third in men, whereas it is the fifth in women. According to a study based on the Osaka Cancer Registry from 1981 to 2003, the incidence rate of HCC was higher in men than in women. Over the past 22 years, the age-standardized incidence rate of HCC in men had climbed from 29.2 per 100,000 cases in 1981 to 41.9 per 100,000 cases in 1987, and then fluctuated within a similar range for 8 years until 1995. After that, there was a gradual declining trend. On the other hand, the age-standardized incidence rate of HCC in women remained static.53

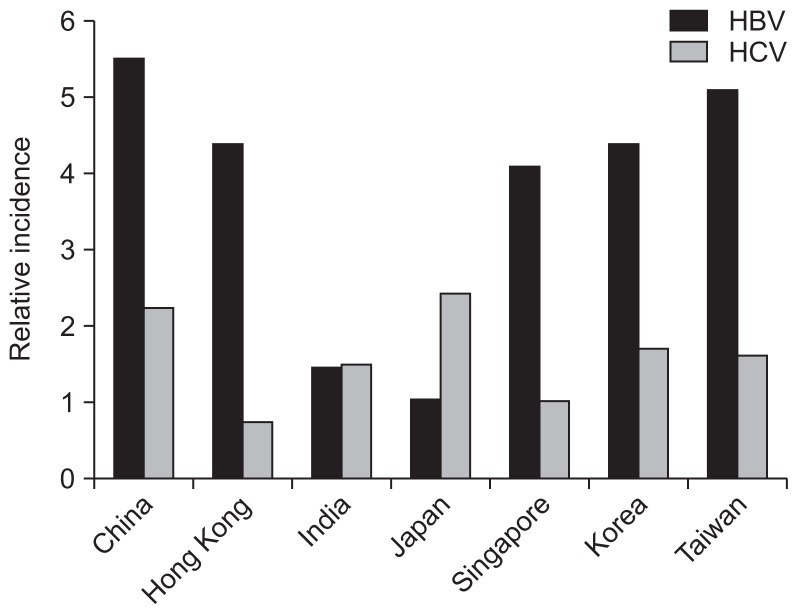

Although Japan is one of Asia-Pacific countries with a high HCC incidence rate, the cause of HCC in Japan differs greatly from other countries in the region. Chronic HCV infection is more common than HBV in Japan (Fig. 3), and hence HCV accounts for 79% of HCC. HBV infection, on the other hand, only accounts for 11% of HCC. A survey from the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan in the period of 1990 to 2003 revealed that anti-HCV-positive cases of HCC accounted for more than 70% of cases diagnosed, whilst HBsAg-positive cases of HCC constituted less than 20% of cases. Some cross-sectional studies derived from Shinshu University Hospital in Japan further showed that HCV-related HCC constitute the vast majority of cases since 1990s. In 2002 to 2007, HCV-related HCC accounted for 72%; HBV-related HCC accounted for 18%; and non-HBV non-HCV HCC (NBNC-HCC) accounted for 10%. Moreover, the nationwide health screening for the seroprevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV in Japanese aged over 40 years found HCV infection to be significantly associated with HCC mortality, this association was, however, not found in HBV infection.54

Fig. 3.

The relative incidences of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in different Asia-Pacific regions.62,63

6. Korea

HCC is substantially prevalent in Korea, ranking as the third common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality. The age-standardized incidence rate is 46.5 per 100,000 populations; 45 per 100,000 in men and 12 per 100,000 in women. The incidence increases when age is over 40 years old, reaching a peak at the age of 55 years. In Korea, HBV infection accounts for 74.2% of HCC; HCV infection accounts for 8.6% of HCC; and heavy alcoholism accounts for 6.9%.55

7. New Zealand

New Zealand is known for its ethnic diversification. At present, Pacific peoples constitute 6.9% of New Zealand population, with 33% of the Pacific population aged under 15 years.56 Therefore, the percentage of Pacific peoples in New Zealand is expected to increase in the future. However, there has been nearly no data on specific cancer incidence rates among Pacific peoples in New Zealand. HCC, as one of the common cancers in Asia-Pacific region, is also prevalent in Pacific peoples. New Zealand census-cancer data from 1981 to 2004 indicates that the age-standardized incidence rate of HCC was 30.3 per 100,000 in men and 9.8 per 100,000 in women, compared with 4.1 per 100,000 and 2.1 per 100,000 for their European counterparts. This suggests that the rate of HCC in Pacific is beyond 7 and 4 times higher than European for men and women, respectively.57

8. Singapore

Based on the Singapore Cancer Registry 2002 to 2005, HCC ranks the fourth most common cancer in men. A survey demonstrated that the age standardized incidence of HCC in men declined from 17.1 per 100,000 in 1968–1972 to 6 per 100,000 in 1988–1992, then increased slowly to 7.1 per 100,000 in 1998–2002. Over this whole time period, the total HCC incidence declined by 58%. At the same time, the rate in women had a similar but slower declining trend, from 2.8 in 1968–1972 to 1.5 per 100,000 persons in 1998–2002.58 According to the records from Ministry of Health in Singapore, the overall prevalence of CHB infection in Singapore has fallen from 9%–10% in 1980–1981 to 4% in 1999. In a cohort study of 288 patients with HCC diagnosed during 2002 to 2007 in the National University Hospital, 74% of patients were male and 76% were of Chinese ethnicity; 35% had CHB; 13% had CHC; and 31.4% had HCC of other causes.

9. Taiwan

A survey from the Taiwan Cancer Registration System documented the incidence rate of HCC had increased gradually in 1994 to 2007. The rate in men was greatly higher than that in women. In 2002, the age-standardized incidence rates were 53 per 100,000 for men and 21 per 100,000 for women. HBV infection is thought to be the most important cause of HCC, but this phenomenon is changing. In 1981 to 1985, HBV-related HCC accounted for 88% of cases, whereas in 1995 to 2000, the proportion of HBV-related HCC had decreased to 59%, whereas the proportion of HCV-related HCC had increased to 31%, with HBV-HCV coinfection accounting for 4% of HCC cases. A study of 18,423 patients with HCC from 1981 to 2001, 67% of male patients with HCC suffered with CHB, but 55% of female patients had HCV-related HCC.59 The average age of patients with HBV-related HCC was 53±14 years, while for those with HCV-related HCC, it was 65±9.1 years (p<0.001). For HBV-related HCC, the ratio between men and women was 6.4; whereas for HCV-related HCC, it was 1.7. During the period between 1981 and 2001, the percentage of HBV-related HCC in men declined from 82% to 66%, and that of women was from 67% to 41%. Overall, the declining incidence of HBV-related HCC was not only due to the effects of universal HBV vaccination,60 but also due to the increase in HCV-related HCC.

CONCLUSIONS

In Asia-Pacific region, HCC remains as a highly prevalent disease with high mortality, although progress has been made through the introduction of HBV vaccination programs. During the period between 2000 and 2005, the incidence and mortality of liver cancer in men is higher than that in women (summarized in Fig. 4).61 For both genders, the incidence of HCC increases with age among ≥40 years.

Fig. 4.

Summary of the age-standardized incidence rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) for men and women in different countries of the Asia-Pacific region between 2000 and 2005. Time periods of the incidences in each country: China, 2002 to 2005; Hong Kong, 2005; India, 2001 to 2004; Japan, 2000; Korea, 2003; New Zealand, 2004; Singapore, 2002 to 2005; and Taiwan, 2002.

The most prevalent etiological agents of HCC in Asia-Pacific region are CHB infection, followed by CHC. The relative incidence of HBV and HCV in each Asian-Pacific country is depicted in Fig. 3.62,63 The major cause of HCC in Asia-Pacific, with the exception of Japan, remains to be HBV. Over the recent 20 years, the incidence of HCC remains static in some countries of the region except for Singapore and Hong Kong where incidence for both genders have a decreasing trend, which could be partly explained by the decline of HBV prevalence.

China has reported an increasing incidence of HCC for both genders which may be due to increasing awareness of record and better screening services. Australia, an immigrant country, is thought traditionally to be very low HCC incidence regions. However, over the last 25 years, there has been an obvious increase (2- to 3-fold) in HCC incidence, which probably due to immigrants from Asia-Pacific and other regions with high prevalence rates of CHB infection. And in Taiwan, there is the increasing incidence of HCC, which is partly due to an increase in HCV-related HCC. Japan, as one of high-risk HCC incidence area, has higher HCV infection compared with HBV infection. The investigation from the Vital Statistics of Japan in 2007 showed that the incidence of HCC was not associated with the infection of HBV, but correlated significantly with the prevalence of HCV. A possible consideration for this discrepancy is the HBV genotype Bj, which shows good clinical progress.54 Therefore, HCV infection plays a more important role in certain countries, e.g., Japan and Taiwan.

Efforts against HCC should be directed toward an effective surveillance program, leading to early diagnosis and effective treatment, and preventive measures for chronic virus hepatitis.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyle P, Levin B. World cancer report 2008. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed F, Perz JF, Kwong S, Jamison PM, Friedman C, Bell BP. National trends and disparities in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, 1998–2003. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kew MC. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010;58:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai CL, Ratziu V, Yuen MF, Poynard T. Viral hepatitis B. Lancet. 2003;362:2089–2094. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordenstedt H, White DL, El-Serag HB. The changing pattern of epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42( Suppl 3):S206–S214. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(10)60507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang JD, Roberts LR. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a global view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:448–458. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomaa AI, Khan SA, Toledano MB, Waked I, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4300–4308. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Bisceglie AM. Epidemiology and clinical presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(9 Pt 2):S169–S171. doi: 10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poon D, Anderson BO, Chen LT, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian Oncology Summit 2009. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalto G, Cervello M, Giannitrapani L, Dantona F, Terranova A, Castagnetta LA. Epidemiology, risk factors, and natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;963:13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumberg BS, Larouzé B, London WT, et al. The relation of infection with the hepatitis B agent to primary hepatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1975;81:669–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Block TM, Mehta AS, Fimmel CJ, Jordan R. Molecular viral oncology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5093–5107. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGlynn KA, London WT. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:3–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen VT, Razali K, Amin J, Law MG, Dore GJ. Estimates and projections of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia among people born in Asia-Pacific countries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:922–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Iloeje UH REVEAL-HBV Study Group. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels and outcomes in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S72–S84. doi: 10.1002/hep.22884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen JD, Yang HI, Iloeje UH, et al. Carriers of inactive hepatitis B virus are still at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related death. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1747–1754. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han YF, Zhao J, Ma LY, et al. Factors predicting occurrence and prognosis of hepatitis-B-virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4258–4270. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Chen CL, et al. Risk stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus e antigen-negative carriers by combining viral biomarkers. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:584–593. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geier A, Gartung C, Dietrich CG. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1721–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200211213472119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sunbul M. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: global distribution and clinical importance. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5427–5434. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan HL, Hui AY, Wong ML, et al. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2004;53:1494–1498. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, et al. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low HBV load. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1140–1149.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu SN, Lin TM, Chen CJ, et al. A case-control study of primary hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer. 1988;62:2051–2055. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881101)62:9<2051::AID-CNCR2820620930>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fasani P, Sangiovanni A, De Fazio C, et al. High prevalence of multinodular hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis attributable to multiple risk factors. Hepatology. 1999;29:1704–1707. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.But DY, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Natural history of hepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1652–1656. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donato F, Tagger A, Gelatti U, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:323–331. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombo M, de Franchis R, Del Ninno E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Italian patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:675–680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109053251002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YJ, Chen Y, Ahsan H, et al. Silencing of glutathione S-transferase P1 by promoter hypermethylation and its relationship to environmental chemical carcinogens in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2005;221:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghebranious N, Sell S. Hepatitis B injury, male gender, aflatoxin, and p53 expression each contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 1998;27:383–391. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang P, Kang D, Cao W, Wang Y, Liu Z. Diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28:109–122. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C, Wang X, Gong G, et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1639–1648. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Diabetes increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population based case control study. Gut. 2005;54:533–539. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohishi W, Fujiwara S, Cologne JB, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in a Japanese population: a nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:846–854. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Law MG, Roberts SK, Dore GJ, Kaldor JM. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia, 1978–1997: increasing incidence and mortality. Med J Aust. 2000;173:403–405. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb139267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kemp W, Pianko S, Nguyen S, Bailey MJ, Roberts SK. Survival in hepatocellular carcinoma: impact of screening and etiology of liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:873–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter SR, Thein HH, Gidding HF, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort infected with hepatitis B or C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1757–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Sullivan BG, Gidding HF, Law M, Kaldor JM, Gilbert GL, Dore GJ. Estimates of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Australia, 2000. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28:212–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2004.tb00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amin J, O’Connell D, Bartlett M, et al. Liver cancer and hepatitis B and C in New South Wales, 1990–2002: a linkage study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka M, Katayama F, Kato H, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma in China: a review of epidemiology and control measures. J Epidemiol. 2011;21:401–416. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan JH, Wang JB, Jiang Y, et al. Attributable causes of liver cancer mortality and incidence in china. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:7251–7256. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.12.7251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou X, Tang Z, Yu Y. Changing prognosis of primary liver cancer: some aspects to improve long-term survival. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 1996;18:211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Zeng H, Zou X. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2010. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:61. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin J. A study on aetiological factors of primary hepato-carcinoma in Tianjin China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1991;12:346–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen JG, Zhu J, Parkin DM, et al. Trends in the incidence of cancer in Qidong, China, 1978–2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1447–1454. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Overview of Hong Kong cancer statistics [Internet] Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2015. [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Available from http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/Statistics.html#cancerfacts. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuen MF, Cheng CC, Lauder IJ, Lam SK, Ooi CG, Lai CL. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma increases the chance of treatment: Hong Kong experience. Hepatology. 2000;31:330–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeole BB. Trends in cancer incidence in esophagus, stomach, colon, rectum and liver in males in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar M, Kumar R, Hissar SS, et al. Risk factors analysis for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with and without cirrhosis: a case-control study of 213 hepatocellular carcinoma patients from India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1104–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka H, Imai Y, Hiramatsu N, et al. Declining incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in Osaka, Japan, from 1990 to 2003. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Umemura T, Ichijo T, Yoshizawa K, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44( Suppl 19):102–107. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park JW. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea: introduction and overview. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;45:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medical Council of New Zealand. Best health outcomes for Pacific peoples: practice implications. Wellington: Medical Council of New Zealand; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meredith I, Sarfati D, Ikeda T, Blakely T. Cancer in Pacific people in New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1173–1184. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernandes ML, Chan YH, Lim SG. Trends in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in Singapore 1968–2002. Hepatology. 2007;46(4 Suppl 1):418A. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu SN, Su WW, Yang SS, et al. Secular trends and geographic variations of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1946–1952. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children: Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1855–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuen MF, Hou JL, Chutaputti A Asia Pacific Working Party on Prevention of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klevens RM, Hu DJ, Jiles R, Holmberg SD. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55( Suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lai CL, Lam KC, Wong KP, Wu PC, Todd D. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma: review of 211 patients in Hong Kong. Cancer. 1981;47:2746–2755. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810601)47:11<2746::AID-CNCR2820471134>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lai CL, Gregory PB, Wu PC, Lok AS, Wong KP, Ng MM. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese males and females: possible causes for the male predominance. Cancer. 1987;60:1107–1110. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870901)60:5<1107::AID-CNCR2820600531>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shiu W, Dewar G, Leung N, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong: clinical study on 340 cases. Oncology. 1990;47:241–245. doi: 10.1159/000226823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leung NW, Tam JS, Lai JY, et al. Does hepatitis C virus infection contribute to hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong? Cancer. 1992;70:40–44. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<40::AID-CNCR2820700107>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheung TK, Lai CL, Wong BC, Fung J, Yuen MF. Clinical features, biochemical parameters, and virological profiles of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]