Abstract

Light chain proximal tubulopathy (LCPT) is characterized by cytoplasmic inclusions of monoclonal LC within proximal tubular cells. The significance of crystalline versus noncrystalline LCPT and the effect of modern therapies are unknown. We reported the clinical-pathologic features of 40 crystalline and six noncrystalline LCPT patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2014. All crystalline LCPTs were κ-restricted and displayed acute tubular injury. One-third of noncrystalline LCPT patients displayed λ-restriction or acute tubular injury. Only crystalline LCPT frequently required antigen retrieval to demonstrate monoclonal LC by immunofluorescence. In five of 38 patients, crystals were not detectable by light microscopy, but they were visible by electron microscopy. Hematolymphoid neoplasms, known before biopsy in only 15% of patients, included 21 monoclonal gammopathies of renal significance; 15 multiple myelomas; seven smoldering multiple myelomas; and three other neoplasms. Biopsy indications included Fanconi syndrome (38%; all with crystalline LCPT), renal insufficiency (83%), and proteinuria (98%). Follow-up was available for 30 (75%) patients with crystalline LCPT and all six patients with noncrystalline LCPT, of whom 11 underwent stem cell transplant, 16 received chemotherapy only, and nine were untreated. Complete or very good partial hematologic remissions occurred in six of 22 treated crystalline LCPT patients. By multivariable analysis, the only independent predictor of final eGFR was initial eGFR, highlighting the importance of early detection. All patients with crystalline LCPT treated with stem cell transplant had stable or improved kidney function, indicating the effectiveness of aggressive therapy in selected patients.

Keywords: Renal pathology, renal proximal tubule cell, multiple myeloma

Intrarenal crystalline deposits of monoclonal Ig and/or light chain are an important cause of renal dysfunction in patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and other dysproteinemias.1,2 The most common Ig-related crystalline nephropathy is light chain cast nephropathy,3 characterized by crystalline precipitates of monoclonal light chain (either κ or λ) within distal tubules. Less commonly, Ig crystallization occurs intracellularly, within proximal tubular cells (light chain proximal tubulopathy [LCPT]),4–7 interstitial histiocytes (crystal-storing histiocytosis [CSH]),8,9 and podocytes,10–12 or intravascularly (crystalglobulinemia).13

In normal physiologic states, small amounts of free light chains are reabsorbed via the megalin/cubilin scavenger receptor on the apical surface of the proximal tubular epithelium followed by endosomal uptake and intralysosomal degradation. In the setting of dysproteinemias, the degree of light chain excretion may exceed the proximal tubule’s reabsorptive capacity, or Tmax, resulting in light chain (Bence–Jones) proteinuria. In LCPT and CSH,9 the reabsorbed light chains are typically of the VK1 subgroup and have innate physicochemical properties that resist proteolysis and promote self-aggregation and crystal formation.4,14–16 Proximal tubular endocytosis of monoclonal light chains generates intracellular oxidative stress, which activates inflammatory mediators and apoptosis.17 Recently, the pathologic spectrum of LCPT has been expanded to include noncrystalline morphology.18–20 The clinical characteristics and prognostic significance of noncrystalline LCPT are uncertain.

Early reports suggested that LCPT was often associated with low-mass multiple myeloma (MGUS) and had a relatively indolent course.4,7,21 Therefore, chemotherapy was usually deferred unless hematologic disease worsened or progressive renal dysfunction ensued, reflecting the serious side effects of alkylating antineoplastic agents.6 The current recommendations from the International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group include chemotherapy or stem cell transplant (SCT) for LCPT, to delay renal progression, and to minimize the risk of recurrence after renal transplantation.22 A few case reports have shown benefits from such therapies in LCPT.23,24

The objectives of this study were to determine the frequency of LCPT in a large renal biopsy population and to delineate the clinical-pathologic characteristics and outcomes of crystalline and noncrystalline LCPT in the current treatment era. We demonstrate that complete or very good partial hematologic remissions are possible in LCPT, with stable kidney function in most patients. We also show that antigen retrieval before immunofluorescence on paraffin sections and careful study by electron microscopy (EM) are essential for accurate diagnosis of LCPT.

Results

Renal Biopsy Findings

Fifty-four patients with LCPT in native kidney biopsies were diagnosed at Columbia University Medical Center from 2000 to 2014 (Table 1). Four patients with diffuse light chain cast nephropathy and four patients with coexistent glomerular disease were excluded from further study. Forty patients (87%) showed proximal tubule crystals (crystalline LCPT) and six patients (13%) showed noncrystalline LCPT.

Table 1.

Biopsy frequency of LCPT compared with other dysproteinemia-related renal diseases

| Pathologic Diagnosis | n (%) |

|---|---|

| AL, ALH, and AH | 451 (41) |

| LCCN | 297 (27) |

| MIDD | 209 (19) |

| LCCN+MIDD | 55 (5) |

| LCPT | 54 (5)a |

| LCCN+AL | 9 (1) |

| AL+MIDD | 2 (<0.5) |

| Total | 1078 |

AH, heavy chain amyloidosis; AL, light chain amyloidosis; ALH, light and heavy chain amyloidosis; LCCN, light chain cast nephropathy; MIDD, monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease.

Includes four patients with light chain cast nephropathy, two patients with amyloid, one patient with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease, and one patient with collapsing glomerulopathy.

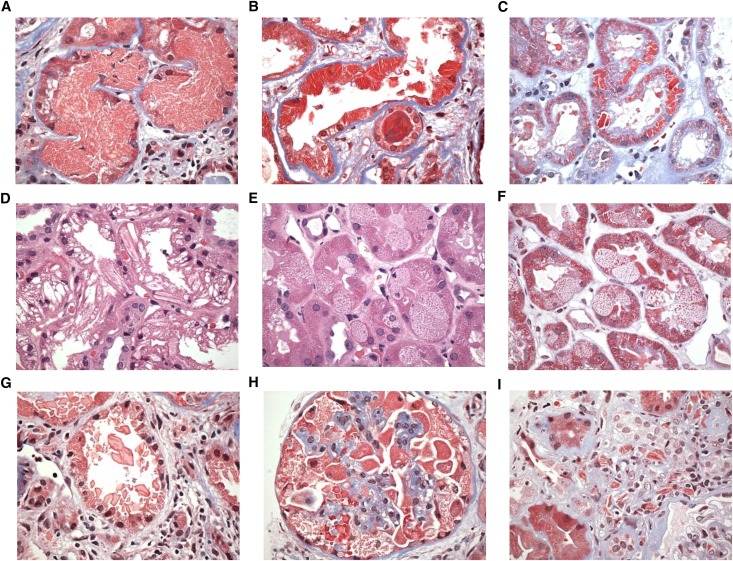

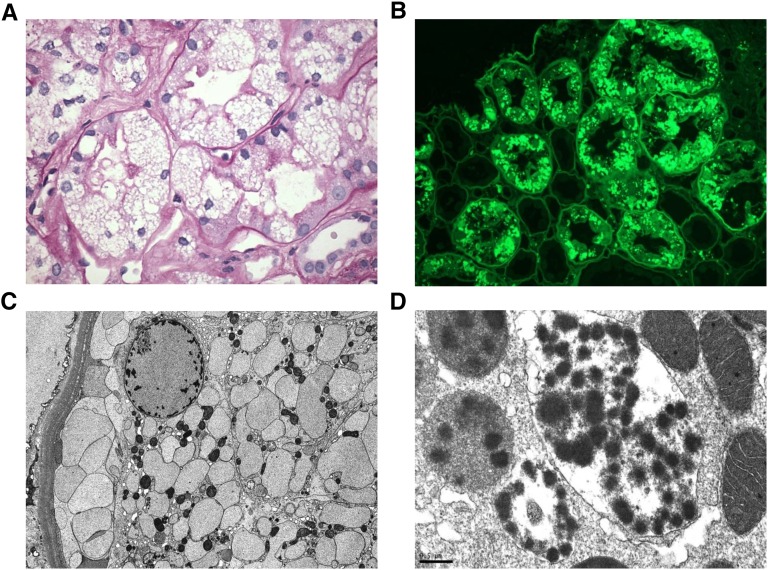

By light microscopy (LM), crystalline inclusions varied in size from small to very large, were usually diffuse in distribution, and displayed various geometric shapes, including rhomboid, rectilinear, or needle-like (Figure 1). In several patients, crystals were extremely focal and sparse, and in five patients they were undetectable by LM. The larger inclusions compressed and distorted the nucleus and were associated with cytoplasmic expansion or ballooning. Crystals were typically strongly eosinophilic, weakly periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reactive, fuchsinophilic, and nonargyrophilic. Rarely, crystals appeared optically clear with all histologic stains, producing angular defects or clefts within the cytoplasm. The noncrystalline LCPT patients displayed droplets/globules (n=4) or vacuoles (n=2) (Figure 2). These droplets were usually fuchsinophilic, but in one patient they were pale blue with trichrome stain. Vacuoles were large and distended the cytoplasm and appeared empty or contained small punctate granular inclusions.

Figure 1.

Light microscopic findings in crystalline LCPT. (A) Proximal tubular cells are engorged by abundant fuchsinophilic small crystalline inclusions that distort the nuclei and obscure the apical cell membrane, filling the tubular lumen. There is adjacent mild interstitial fibrosis and inflammation without tubulitis (trichrome, ×600). (B) Proximal tubular cells are distorted by elongated highly fuchsinophilic needle-shaped inclusions. Some of the tubular cells are flattened, and others display shedding of cytoplasmic fragments into the lumen. An atypical hard cast is present in a distal tubule (trichrome, ×600). (C) Distinct crystals of varying size and number are brightly trichrome-red and exhibit a variety of geometric shapes from rectangular to rhomboidal (trichrome, ×400). (D) The proximal tubular cells contain abundant large, elongated, optically clear, or weakly eosinophilic crystals that distort the cell architecture (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×600). (E) There is variable individual proximal tubular cell vacuolation containing finely granular punctate eosinophilic inclusions that could be resolved as crystalline only at the ultrastructural level. Some proximal tubular nuclei appear to be undergoing apoptosis. (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×600). (F) The same biopsy as Figure 1E shown with trichrome stain highlights the granular trichrome-red inclusions and vacuolated appearance of individual proximal tubular cells side by side with more normal appearing cells (trichrome, ×600). (G) Crystals are shed from the apical surfaces of injured proximal tubular cells into the tubular lumen, forming atypical loose casts with sharp edges. No giant cell reaction is seen. The adjacent interstitium is expanded by fibrosis and chronic inflammation (trichrome ×600). (H) A glomerulus with abundant crystalline inclusions within the cytoplasm of engorged podocytes (trichrome, ×600). (I) An example of crystal-storing histiocytosis with needle-shaped fuchsinophilic crystals within the cytoplasm of interstitial histiocytes. Similar crystals are present in the proximal tubular cells of an adjacent tubule at bottom left (trichrome, ×600).

Figure 2.

Pathologic features of noncrystalline LCPT. (A) The proximal tubular cells are variably distended by abundant PAS-negative vacuoles associated with focal loss of brush border (PAS, ×600). (B) By immunofluorescence performed on pronase-digested paraffin sections, the vacuoles stain intensely for κ light chain (FITC-conjugated antisera to κ light chain, ×400). (C) By EM, the vacuoles appear rounded or ovoid and contain finely granular material without crystal formation. The numerous membrane-bound vesicles extend from the apical to the basal cytoplasm and crowd out the mitochondria, which appear reduced in size and number (Magnification, ×5000). (D) A different case of noncrystalline LCPT exhibits membrane-bound phagolysosomes with a mottled appearance owing to rounded electron-dense particulate inclusions suspended free on an electron-lucent background or within a moderately electron-dense amorphous matrix. The adjacent mitochondria appear well preserved (Magnification, ×40,000).

All crystalline LCPT biopsies showed acute tubular injury (ATI), which was diffuse/severe in most (88%) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1). Features of ATI included focal or diffuse loss of brush border, ragged disrupted cytoplasm, apical shedding of cytoplasmic fragments, enlarged reparative nuclei with nucleoli, and individual cell apoptosis. The proximal tubular lumen focally contained sloughed epithelial cells with crystalline inclusions resembling light chain casts. The four biopsies with normal-appearing proximal tubules all had noncrystalline LCPT. Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis were mild or moderate in most patients. Interstitial fibrosis was typically associated with mononuclear interstitial inflammation, but tubulitis was not a feature.

Table 2.

Pathologic findings in LCPT

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total no. of participants | 46 |

| Crystalline | 40c |

| Noncrystalline | 6 |

| κ LC | 43/45 (96)d |

| Detection by IF-frozen | 15/43 (35) |

| Detection by IF-pronase | 37/38 (97) |

| ATI scorea | |

| Absent | 4 |

| Mild/patchy | 6 |

| Severe/diffuse | 36 |

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy scoreb | |

| 0 | 11 |

| 1 | 17 |

| 2 | 15 |

| 3 | 3 |

| Interstitial inflammationb | |

| 0 | 13 |

| 1 | 28 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 0 |

| Tubular casts | |

| Absent | 37 |

| Focal | 9 |

LC, light chain.

0=absent, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe.

Scores: 0 (absent), 1 (<25% of cortical area), 2 (25%–49% of cortical area), and 3 (≥50% of cortical area).

Five patients showed crystals by EM only.

One case that did not stain for κ or λ light chain by IF performed on both frozen and pronase-digested paraffin tissue was known to have monoclonal κ light chain in urine.

Nine biopsies showed atypical casts in proximal and/or distal tubules (all with <5 casts per 100 tubular profiles). These casts typically had a similar structure to the intracellular crystals, suggesting their origin from lysed proximal tubular cells. Five crystalline LCPT patients displayed crystalline inclusions in other intrarenal cells, including histiocytes (n=4), podocytes (n=3), and/or parietal epithelial cells (n=1).

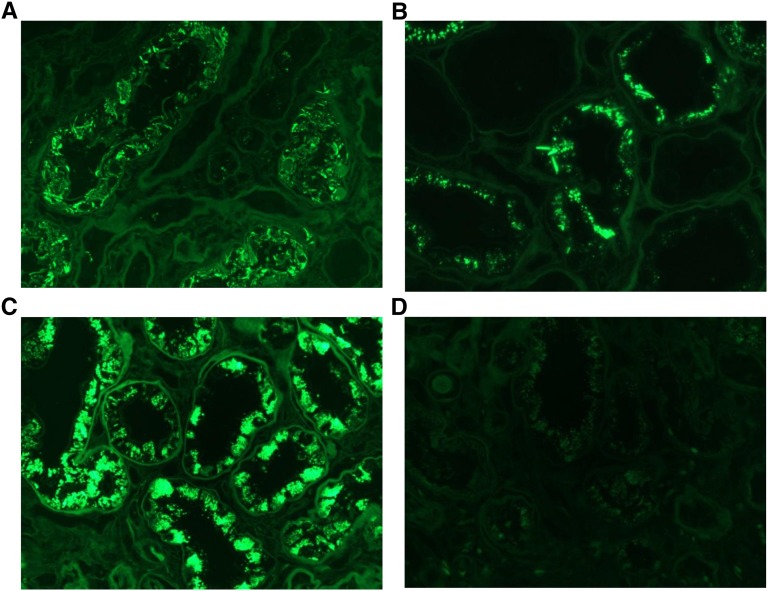

Forty-five patients showed light chain–restricted cytoplasmic staining of proximal tubules, by immunofluorescence on frozen tissue (IF-F), by immunofluorescence after pronase digestion (IF-P) or by immunoperoxidase (IP) stain (Figures 2 and 3). In one patient with crystalline LCPT with smoldering MM, both IF-F and IF-P were negative; however, the plasma cell neoplasm was known to be κ-restricted. All other crystalline LCPT biopsies stained for κ, whereas two of the six noncrystalline LCPT biopsies stained for λ. The sensitivity of IF-F and IF-P for detection of LCPT was 35% (15/43) and 97% (37/38), respectively. IF-F was significantly better for detecting noncrystalline LCPT than crystalline LCPT (P<0.003).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence characteristics of crystalline LCPT. (A) An instance with needle-shaped crystals of κ light chain seen by immunofluorescence performed on pronase-digested paraffin sections. These crystals were not visible by routine IF performed on frozen sections (not shown). (FITC-conjugated antisera to κ light chain, ×600). (B) An instance with both needles and smaller granular inclusions is revealed after pronase digestion on paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed tissue (FITC-conjugated antisera to κ light chain, ×600). (C) An instance with proximal tubular engorgement by granular inclusions staining for κ light chain after pronase digestion on paraffin-embedded tissue. These inclusions were visible to a lesser extent by staining of frozen tissue (not illustrated) (FITC-conjugated antisera to κ light chain, ×600). (D) The same biopsy as Figure 3C shown with negative staining for λ light chain performed on pronase-digested paraffin sections (FITC-conjugated antisera to λ light chain, ×600).

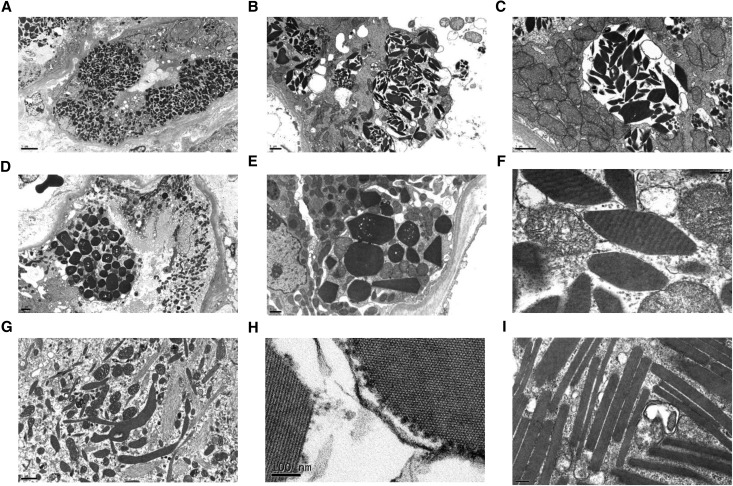

EM of proximal tubules was performed in 38 patients with crystalline LCPT and all six noncrystalline patients (Figures 2C and 4). In five patients, crystals were seen by EM but not by LM (Figure 1E). The crystalline patients demonstrated intracytoplasmic inclusions that were rhomboidal, polygonal, rectangular, rod-shaped, or needle-like (Figure 4). Most appeared uniformly electron dense but at extremely high magnifications (>50,000×), some demonstrated fibrillar (n=6), lattice-like (n=1), or periodic/striated substructures (n=1) (Figure 4H). Some inclusions were membrane-bound within endosomes or phagolysosomes, whereas others appeared to lie free in the cytosol. When abundant, crystals often distorted the nuclear contours and displaced mitochondria, with focal mitochondrial swelling. Many patients had focal blunting or loss of brush border and shedding of cytoplasmic organelles into the tubular lumen. The noncrystalline LCPT patients demonstrated cytoplasmic droplets (n=4), granules (n=1), or vacuoles (n=1) (Figure 2). One biopsy also showed mild diffuse glomerular basement membrane thickening, consistent with very mild diabetic changes.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural findings in crystalline LCPT. (A) A low power view shows full thickness (apical to basal) engorgement of individual proximal tubular cells by crystals of varying size and shape, causing compression of the nuclear contours. The apical brush border is swollen or lost. The less-involved cells have an increased number of electron lucent endosomes and electron dense phagolysosomes (Magnification, ×3000). (B) A severely injured proximal tubular cell contains multiple membrane-bound phagolysosomes distended by randomly oriented crystals, some of which appear to have broken out into the cytosol. There is complete loss of the apical brush border with cytolysis and shedding of crystals and mitochondria into the tubular lumen (Magnification, ×10,000). (C) A higher power view of an individual membrane-bound phagolysosome from Figure 3B illustrates fusion of endosomes (smaller membrane-bound vesicles) within the larger phagolysosome, which is distended by randomly oriented crystals exhibiting predominantly rhomboidal shapes. The adjacent mitochondria appear swollen with disrupted and dysmorphic cristae (Magnification, ×20,000). (D) On low power view, some proximal tubular cells are markedly engorged by crystals, whereas others are completely spared but show degenerative changes with loss of brush border and epithelial simplification (Magnification, ×4000). (E) A high-power view of a proximal tubular cell from the same instance as Figure 3D illustrates a range of crystalline shapes from hexagonal to pentagonal or triangular. Most of the crystals appear to lie free within the cytosol (Magnification, ×10,000). (F) On high-power examination, individual crystals exhibit a periodicity seen as cross-hatching or vague striations (Magnification, ×80,000). (G) An example of elongated feathery phagolysosomes with branching architecture containing solid, needle-like, or fibrillary structures, some of which lie free in the cytoplasm (Magnification, ×15,000). (H) At 100,000× magnification, individual crystals are seen to be composed or repeating smaller subunits with 10 nm periodicity, shown longitudinally and in cross-section. These smaller repeating structures may represent individual light chain molecules arrayed in linear parallel sequence within the larger crystal. Rounded ribosomes are adherent to the edge of the crystal (Magnification, ×120,000). (I) A patient with elongated rectangles forms rod-shaped structures that were present both within the podocyte cytoplasm and the proximal tubular epithelium (not shown). Each of these rectangles is composed of parallel linear arrays (Magnification, ×60,000).

Clinical Characteristics

Most patients were men (63%); 38 were white, three were Hispanic, two were black, and three were of unknown race (Table 3). The median age was 60 years (range, 39–87 years). Twenty-two patients had preexisting hypertension, and two had diabetes mellitus. Hematolymphoid neoplasms (HLNs), including monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) (n=21), MM (n=15), smoldering MM (n=7), non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) (n=2), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=1), were diagnosed shortly after renal biopsy in 38 patients, before renal biopsy in seven patients, and 3 years later in one patient. Two patients with MM received chemotherapy before diagnosis of LCPT.

Table 3.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of LCPT

| Characteristic | All Patients (n=46) | Crystalline (n=40) | Noncrystalline (n=6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yra | 62.5 (60) | 61.4 (59) | 74.5 (72) |

| (Range) | (39–87) | (39–87) | (61–87) |

| Male (%) | 63 | 68 | 33 |

| White (%) | 85 | 83 | 100 |

| Serum monoclonal spike | 32/45 (71%) | 27/39 (69%) | 5/6 (83%) |

| Urine monoclonal spike | 31/33 (94%) | 29/30 (97%) | 2/3 (66%) |

| Positive FLC | 10/11 (91%) | 8/9 (89%) | 2/2 (100%) |

| Hematologic diagnoses | |||

| MM | 15 | 10 | 5 |

| Smoldering myeloma | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| MGRS | 21 | 21 | 0 |

| Other diagnosesb | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| FS | 17/43 (40%) | 17/38 (43.4%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| SCr, mg/dla | 2.38 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.0) |

| eGFR by CKD-EPI, ml/min per 1.73 m2a | 38.3 (36.4) | 35.3 (34.6) | 53.8 (60.5) |

| eGFR<60, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 38/46 (83%) | 35/40 (88%) | 3/6 (50%) |

| AKI | 10/46 (22%) | 8/40 (20%) | 2/6 (33%) |

| Proteinuria, g/24 ha | 3.07 (2.51) | 2.97 (2.45) | 4.4 (4.2) |

| <1 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| 1–3 | 23 | 23 | 0 |

| >3 | 17 | 13 | 4 |

| Serum albumin, g/dlc | 4.0±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 4.1±0.2 |

CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 2009 formula28; FLC, free light chain assay; SCr, serum creatinine.

Values are mean (median).

Other diagnoses: non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=2) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=1).

Mean±SEM.

Forty-three patients had a monoclonal spike: in serum only (n=12), both serum and urine (n=21), or urine only (n=10) (Supplemental Table 2). Two patients with no detectable monoclonal spike were diagnosed with MM or MGUS several months and 3 years postbiopsy, respectively. In one patient with MM, serum and urine electrophoresis studies were unavailable. Serum-free light chain assay was abnormal in ten of 11 patients tested, all of whom had monoclonal spikes in serum and/or urine. Bone marrow biopsy findings available in 37 patients included plasma cell neoplasm (n=30), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=1), NHL (n=1), and no evidence of HLN (n=5). One patient with negative bone marrow biopsy had splenic NHL.

Seventeen of 45 patients tested (38%), all in the subgroup with crystalline LCPT, had one or more features of Fanconi syndrome (FS), including normoglycemic glycosuria (n=15), metabolic acidosis (n=7), hypophosphatemia (n=5), hypouricacidemia (n=5), bone pain (n=3), and aminoaciduria (n=2). Twenty-seven subjects reportedly had no signs of FS, but detailed test results were not available for confirmation. Most patients had renal insufficiency (83%) and/or proteinuria (98%). In ten patients (22%), renal insufficiency was described as acute, but baseline serum creatinine data were not available in all of these patients. Urine protein excretion was often heavy (>1 g/d in 87% and >3 g/d in 37%) (Table 3), but hypoalbuminemia was not seen.

Follow-Up

Follow-up data were available for 30 crystalline LCPT patients (75%) (median, 39 months; range, 1–141 months) and all six (100%) noncrystalline patients (median, 14.5 months; range, 5–24 months). Twenty-seven patients received chemotherapy, with SCT in 11, and nine patients received no treatment. Two patients progressed from MGRS to MM (at 54 and 71 months) before receiving therapy. In the remaining patients, treatment was started shortly after the diagnosis of LCPT. Chemotherapies included various combinations of dexamethasone, bortezomib, thalidomide, lenalidomide, alkylating agents, and rituximab, often sequentially (Supplemental Table 3, Table 4). Of note, 21 of 27 treated patients were diagnosed after 2006, whereas six of nine untreated patients were diagnosed before 2006.

Table 4.

Chemotherapeutic agents used in LCPT patients

| Therapeutic Agent | n |

|---|---|

| Bortezomib | 12 |

| Thalidomide | 9 |

| Lenalidomide | 6 |

| Chemotherapy, unspecified type or other agent | 5 |

| Rituximab | 4 |

| Melphalan | 3 |

| CDEP | 3 |

| CHOP | 1 |

| Steroids | 1 |

Most patients received more than one line of therapy. CDEP, cyclophosphamide+dexamethasone+etoposide+cisplatin; CHOP, cyclophosphamide+doxorubicin+vincristine+prednisone.

Outcomes for the crystalline LCPT patients are presented in Table 5. Treatment responses included complete hematologic remission (CR) in five patients, very good partial remission (VGPR) in one patient, and partial remission (PR) in three patients (Table 5). The remaining 21 patients all had stable hematologic disease (SD) at last follow-up. Nineteen patients (including two noncrystalline LCPT patients) had persistent urinary light chain excretion at last follow-up, which was associated with normal kidney function in three patients, CKD in 13 patients, ESRD in two patients, and no renal follow-up data in one patient. Two subjects presented with ESRD; 24 had CKD, albeit with improvement in serum creatinine in ten subjects; and three had normal kidney function (including one who presented with AKI). One subject who died 1 month postbiopsy had no renal follow-up data. No patient had doubling of serum creatinine. Median kidney survival from the time of kidney biopsy (censored for patient death) for the group of crystalline LCPT was 135±5.5 months.

Table 5.

Outcomes versus treatment in 30 crystalline LCPT patients

| Characteristic | SCT+Chemotherapy (n=10) | Chemotherapy Alone (n=12) | None (n=8) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), yr | 51 (39–59) | 67.5 (47–85) | 65 (47–87) | 0.001 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.002 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.003 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.79 | ||||

| MM | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0.05 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.07 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.07 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none >.99 | ||||

| Smoldering MM | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.06 |

| MGRS | 3 | 6 | 3 | 0.65 |

| Other HLN | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.10 |

| eGFR (initial)a | 48.8 (49.8) | 30.0 (32.0) | 34.8 (37.9) | 0.19 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.09 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.25 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.52 | ||||

| sCr, mg/dl (initial)a | 2.01 (1.55) | 2.48 (2.15) | 2.38 (1.85) | 0.48 |

| Proteinuria (initial), g/24 ha | 3.05 (1.41) | 2.95 (2.95) | 2.15 (1.89) | 0.01 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.01 | ||||

| SCT versus none >.99 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.03 | ||||

| Follow-up monthsa | 65.2 (57.5) | 40.5 (32.0) | 59.0 (48.5) | 0.60 |

| eGFR (final)ab | 58.9 (51.5) | 31.0 (27.8) | 27.9 (33.5) | 0.01 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.01 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.01 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.94 | ||||

| eGFR<60 (final)ab | 7/10 | 12/12 | 7/7 | 0.32 |

| Change in eGFR | +10.1 (+7.6) | +1.0 (-4.5) | −6.9 (-4.9) | 0.04 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.16 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.06 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.57 | ||||

| sCr (final), mg/dlab | 1.43 (1.45) | 2.27 (2.07) | 3.11 (1.75) | 0.05 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.03 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.07 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.87 | ||||

| Proteinuria (final), g/24 hab | 0.85 (0.80) | 1.56 (1.59) | 1.96 (1.92) | 0.05 |

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.15 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.02 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.39 | ||||

| Hematologic outcomes | 0.12 | |||

| CR | 2/10 | 3/12 | 0/8 | 0.39 |

| VGPR | 1/10 | 0/12 | 0/8 | 0.62 |

| PR | 2/10 | 0/12 | 1/8 | 0.35 |

| Stable disease | 5/10 | 9/12 | 7/8 | 0.24 |

| Renal functional outcomesbc | 0.07 | |||

| SCT versus chemotherapy 0.16 | ||||

| SCT versus none 0.12 | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus none 0.66 | ||||

| Improved | 4/10 | 3/12 | 1/7 | |

| Stable | 6/10 | 5/12 | 4/7 | |

| Worsening CKD | 0/10 | 4/12 | 0/7 | |

| ESRD | 0/10 | 0/12 | 2/7 | |

| Death | 0/10 | 4/12 | 3/8 | 0.12 |

SCr, serum creatinine.

Values are mean (median).

One untreated patient had no renal follow-up data.

Improved: ΔSCr>–0.5 mg/dl; stable: ΔSCr±0.5 mg/dl from baseline; worsening: ΔSCr>0.5 mg/dl.

Three of the six patients with noncrystalline LCPT had normal kidney function and no evidence of ATI. All three patients were biopsied for heavy proteinuria (7.4, 7.0, and 4.1 g, respectively) that consisted predominantly of free light chains, rather than albumin. One of these patients was treated with chemotherapy and had CR, resolution of proteinuria, and stable normal renal function. A second patient treated with chemotherapy had resolution of light chain proteinuria but worsening of renal function after exposure to zoledronate. The third patient, who was untreated, has persistent light chain proteinuria but stable normal renal function after 10 months, suggesting possible physiologic trafficking of light chains (Supplemental Figure 5). The remaining three noncrystalline LCPT patients all received chemotherapy (with SCT in one patient). Two patients had SD, and one patient had partial hematologic remission; two patients had CKD, and one patient presented with ESRD. Median kidney survival from the time of kidney biopsy was 64±17.8 months for the six patients with noncrystalline LCPT.

Two patients with crystalline LCPT underwent repeat biopsies. One patient had untreated MGRS and worsening CKD, with persistent crystalline LCPT, increased tubulointerstitial scarring, and a new finding of CSH in the second biopsy performed after 46 months. The other subject had MGRS and worsening CKD, despite partial hematologic response to chemotherapy. Repeat biopsy after 84 months showed persistent crystalline LCPT and no increase in tubulointerstitial scarring.

Nine of the 36 patients with follow-up died, including three untreated patients, one who underwent SCT, and 5 others who received chemotherapy alone. One subject died after 1 month; the mean time from renal biopsy to death for the remaining eight patients was 24.6 months (median, 22 months; range, 13–48 months). At the time of death, seven patients had SD, and one patient had PR. Two of these eight subjects presented with ESRD; the remaining six had CKD at the time of death. The cause of death was undetermined because none of these patients underwent autopsy.

Clinical-pathologic Correlations

The presence of rare casts did not correlate with initial or final kidney function. There was a trend for crystalline LCPT to be associated with younger age, FS, higher incidence of MGRS, less proteinuria, and worse kidney function; however, patients with noncrystalline LCPT were too few for robust statistical comparison (Table 3). All eight crystalline LCPT patients with improved kidney function at last follow-up displayed ATI (diffuse, n=5; patchy, n=3). However, 16 of 19 patients with stable kidney function also displayed diffuse (n=12) or patchy (n=4) ATI, including five patients with initially normal kidney function (Supplemental Tables 1–3). Therefore, the presence or severity of ATI did not correlate with kidney function at presentation or last follow-up. Patients receiving SCT were younger, more likely to have MM, and had the best initial and final renal function and urinary protein levels (Table 5). In all of the patients, initial and final eGFR correlated inversely with age, extent of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, and percent of interstitial inflammation. By multivariable linear regression analysis, predictors of initial eGFR included age and degree of tubulointerstitial scarring and inflammation. The only predictor of final eGFR was initial eGFR (for all LCPT patients) and age (for crystalline patients only) (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

We report the largest cohort of LCPT with detailed clinical-pathologic correlations and hematologic and renal outcomes in the modern era. The low biopsy frequency (5%) of LCPT among dysproteinemia-related renal diseases in this study is remarkably similar to previous descriptions,18,20 but the true incidence and prevalence of this condition are unknown because renal biopsy is biased toward patients with unexplained renal insufficiency and/or significant proteinuria. A third of our patients, all with crystalline LCPT, had documented signs of FS (most commonly normoglycemic glycosuria), but this was likely under-recognized because comprehensive testing for proximal tubular dysfunction was not performed in many patients. LCPT was the first clinical-pathologic manifestation of dysproteinemia in most (85%) patients, and transformation to MM occurred rarely, suggesting that the neoplastic clone is usually stable.

Complete or very good partial hematologic remissions were achieved in one-third of treated patients, with lowest mortality and best hematologic outcomes seen in patients receiving SCT. Although the patients who received SCT were more likely to have MM (60%), they were overall younger than those given chemotherapy alone or no treatment, consistent with selection bias. However, persistent hematologic disease was seen in most patients, including those who received SCT. Two earlier studies described ESRD and/or doubling of serum creatinine in 16%6 and 40% of patients4 of dysproteinemia-related FS. In our study, ESRD was uncommon (8%), and doubling of serum creatinine did not occur. However, the follow-up times (median of 39 months for crystalline patients and 14.5 months for noncrystalline patients) were unlikely to capture all patients with progressive CKD in this cohort. Importantly, 78% of patients had CKD at last follow-up, despite some improvement in serum creatinine in 33%. Patients who received SCT had better renal outcomes compared with nontreated patients and those receiving chemotherapy alone, possibly reflecting in part their younger age and better overall health status. These findings demonstrate that although initial renal insufficiency may be partly reversible (correlating with the high prevalence of ATI), CKD remains common in LCPT in the current treatment era. Of note, most patients with persistent urinary LC excretion after treatment demonstrated stable or improved kidney function, suggesting changes in pathogenic light chain load or tubular repair. Longer follow-up is required to determine whether ongoing urinary light chain excretion in these patients has any long-term effect on kidney survival.

We diagnosed noncrystalline LCPT in 13% of patients compared with 77%18 and 43%20 in two recent studies. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear and do not appear related to differences in biopsy indications or pathologic criteria. Our data suggest that noncrystalline LCPT is particularly uncommon, but more patients are necessary to determine if there are significant clinical and prognostic differences between crystalline and noncrystalline LCPT. Most crystalline LCPT required pronase digestion of formalin-fixed sections for detection of monoclonal light chains, whereas noncrystalline LCPT could be detected by immunofluorescence microscopy (IF) on frozen tissue in all patients.18–20 Crystalline inclusions are an abnormal finding, but it is possible that some noncrystalline LCPT patients that are biopsied for light chain proteinuria and have normal kidney function and no ATI represent physiologic trafficking of light chains. The preserved kidney function despite persistent light chain proteinuria in one untreated patient supports this possibility. However, given the small number of patients and relatively short follow-up time, this hypothesis remains speculative. Likewise, our data show that the morphologic finding of light chain crystalline inclusions in the proximal tubular cytoplasm is often not a harbinger of progressive renal failure. In fact, >50% of patients with crystalline LCPT and persistent dysproteinemia did not show renal disease progression, and many had no clinical evidence of FS. Careful clinical-pathologic correlation may help better define a subset of patients with intracytoplasmic proximal tubular monoclonal light chains that is of limited or uncertain renal significance.

One-fifth of our patients displayed coexistent rare light chain casts, which did not correlate with clinical presenting features or outcomes, implying limited significance. Of note, distal tubule light chain casts were noted in two previous studies of LCPT, in five of eight patients4 and three of seven patients.21 In our patients, casts appeared to be derived predominantly from sloughing of crystal-laden epithelial cells within proximal tubules. We found light chain crystals in other intrarenal cells besides proximal tubules in 10% of crystalline LCPT. Messiaen et al.4 reported renal CSH in seven of 11 patients, whereas nine of 17 patients reviewed by Maldonado et al.7 had lymphoplasmacytic crystalline inclusions in bone marrow cells. Together, these findings suggest that crystalline LCPT may be accompanied by crystalline inclusions in other cell types, either in the kidney, bone marrow, or other organs.23 Renal CSH may have contributed to the development of interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and renal insufficiency in some of our patients, whereas podocyte light chain crystals may have contributed to nephrotic-range proteinuria in one patient.

This study has several limitations, including incomplete clinical data and a small number of noncrystalline LCPT patients, which precluded robust statistical comparison with crystalline patients. As a retrospective study involving multiple different nephrology and oncology centers, laboratory testing, renal biopsy indication, and choice of therapy were not standardized and may have affected outcomes. Classification of HLNs and outcomes were based largely on summary data supplied by the treating physicians, without details of confirmatory laboratory findings in all patients. Finally, the heterogeneous pathologic findings, within individual patients with LCPT, likely affected clinical presenting features and outcomes.

In summary, LCPT presents unusual diagnostic challenges because most patients have no prior history of hematolymphoid disease, intracytoplasmic light chain inclusions may be undetectable by routine immunofluorescence, and crystals may not be visible by LM. Crystalline LCPT was the major form and demonstrated ATI and κ-restriction in all patients. Although one-third of treated LCPT patients had complete or partial hematologic remissions, most treated patients had persistent hematologic disease, indicating that current therapies do not always eliminate the pathogenic clone. The only independent predictor of final eGFR was initial eGFR, highlighting the importance of early detection. Most treated patients, including all patients with crystalline LCPT receiving SCT, demonstrated stable or improved kidney function, indicating the benefit of aggressive therapy in selected patients with LCPT. Progression to ESRD was rare, but CKD was common, and longer follow-up may uncover a greater burden of slowly progressive CKD in patients with treated LCPT.

Concise Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center. The renal biopsy database between 2000 and 2014 was searched for all patients with a diagnosis of MM, amyloidosis (light chain amyloidosis, light and heavy chain amyloidosis, or heavy chain amyloidosis), monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease, and/or LCPT. Renal biopsies were performed for standard clinical indications in all patients. The diagnosis of LCPT required light chain–restricted staining of proximal tubular cytoplasm by IF and the presence of intracytoplasmic proximal tubular inclusions by LM or EM. Crystals were defined as inclusions possessing at least one straight edge. All other instances of LCPT were classified as noncrystalline. After excluding patients with coexistent light chain cast nephropathy (n=4), amyloidosis (n=2), monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease (n=1), or collapsing glomerulopathy (n=1), there were 40 patients with crystalline LCPT and six patients with noncrystalline LCPT. All renal biopsies were processed for LM, IF, and EM according to standard techniques. Ten patients were referred for second opinion and performance of IF on pronase-digested paraffin sections. For LM, patients were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, PAS, Masson’s trichrome, and Jones methenamine silver; Congo red was used in select patients. IF was performed in 45 patients, on frozen tissue (IF-F) in 43 patients, and on pronase-digested formalin-fixed tissue (IF-P) using a previously described technique25 in 38 patients. IP staining of formalin-fixed tissue was performed in two patients. EM was performed in 44 patients. Clinical and pathologic details are provided in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

For patients of LCPT only, the diagnosis of HLN and follow-up information were obtained from the electronic medical record and from the treating physicians. Diagnoses and treatment responses were on the basis of standard criteria.26,27 A diagnosis of MM was on the basis of the presence of (1) monoclonal Ig in serum and/or urine, (2) presence of at least 10% monoclonal plasma cells in bone marrow, and (3) one or more of the following signs of organ damage: hypercalcemia, serum creatinine >2 mg/dl, anemia, and/or lytic bone lesions. Smoldering MM was diagnosed if both options 1 and 2, but not option 3, of the criteria were present; MGUS was diagnosed if there was a monoclonal Ig in serum and/or urine but other criteria for MM were not fulfilled. Following the diagnosis of LCPT, all patients with MGUS were reclassified as MGRS. CKD was defined as eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 2009 formula.28 ESRD was defined as irreversible kidney failure requiring RRT. CR was defined according to the “International Uniform Response Criteria for Multiple Myeloma”27 as negative serum and urine immunofixation (although this was not confirmed by repeat bone marrow biopsy); VGPR was defined as positive monoclonal protein on immunofixation but not by electrophoresis or ≥90% reduction in serum monoclonal protein plus urine monoclonal protein level <100 mg/24 h; PR was defined as ≥50% reduction in serum monoclonal protein and ≥90% reduction in urine monoclonal protein or <200 mg/24 h.27 Treated patients not meeting criteria for CR, VGPR, PR, or progressive disease were classified as SD.27 Renal functional outcomes were stratified on the basis of change in serum creatinine from initial presentation to last follow-up as >±0.5 mg/dl, <0.5 mg/dl, or ESRD.

Statistical analyses was performed using nonparametric exact statistical methods, including the Fisher exact test (for categorical variables), the Wilcoxon rank-sum (or Mann–Whitney U) test (for continuous variables between two groups), the Kruskal–Wallis test, and the Jonckheere–Terpstra test (for categorical or continuous variables among three or more ordered or hierarchical groups). Comparison of 2 continuous variables was performed by univariate and multivariable linear regression analysis. For outcomes, CR, VGPR, PR, and SD were treated as a hierarchical categorical variable (i.e., trending CR to VGPR to PR to stable from best to worse), and the three treatment groups were also analyzed as a hierarchical categorical variable (i.e., trending SCT better than chemotherapy alone better than no treatment). Kidney survival (Kaplan–Meier analysis) was calculated from the day of kidney biopsy and censored for patient death. Analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL) and StatXact 6.0 for Windows (Cytel, Cambridge, MA). Continuous variables are reported as the mean (median) or mean±SD. Statistical significance was assumed at P<0.05.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many nephrologists who submitted biopsies and clinical information.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015020185/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Leung N, Nasr SH: Myeloma-related kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 21: 36–47, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herlitz LC, D’Agati VD, Markowitz GS: Crystalline nephropathies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 136: 713–720, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasr SH, Valeri AM, Sethi S, Fidler ME, Cornell LD, Gertz MA, Lacy M, Dispenzieri A, Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Leung N: Clinicopathologic correlations in multiple myeloma: A case series of 190 patients with kidney biopsies. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 786–794, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messiaen T, Deret S, Mougenot B, Bridoux F, Dequiedt P, Dion JJ, Makdassi R, Meeus F, Pourrat J, Touchard G, Vanhille P, Zaoui P, Aucouturier P, Ronco PM: Adult Fanconi syndrome secondary to light chain gammopathy. Clinicopathologic heterogeneity and unusual features in 11 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 79: 135–154, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridoux F, Sirac C, Hugue V, Decourt C, Thierry A, Quellard N, Abou-Ayache R, Goujon JM, Cogné M, Touchard G: Fanconi’s syndrome induced by a monoclonal Vkappa3 light chain in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 749–757, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma CX, Lacy MQ, Rompala JF, Dispenzieri A, Rajkumar SV, Greipp PR, Fonseca R, Kyle RA, Gertz MA: Acquired Fanconi syndrome is an indolent disorder in the absence of overt multiple myeloma. Blood 104: 40–42, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maldonado JE, Velosa JA, Kyle RA, Wagoner RD, Holley KE, Salassa RM: Fanconi syndrome in adults. A manifestation of a latent form of myeloma. Am J Med 58: 354–364, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokes MB, Aronoff B, Siegel D, D’Agati VD: Dysproteinemia-related nephropathy associated with crystal-storing histiocytosis. Kidney Int 70: 597–602, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Hamel C, Thierry A, Trouillas P, Bridoux F, Carrion C, Quellard N, Goujon JM, Aldigier JC, Gombert JM, Cogné M, Touchard G: Crystal-storing histiocytosis with renal Fanconi syndrome: Pathological and molecular characteristics compared with classical myeloma-associated Fanconi syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2982–2990, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akilesh S, Alem A, Nicosia RF: Combined crystalline podocytopathy and tubulopathy associated with multiple myeloma. Hum Pathol 45: 875–879, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasr SH, Preddie DC, Markowitz GS, Appel GB, D’Agati VD: Multiple myeloma, nephrotic syndrome and crystalloid inclusions in podocytes. Kidney Int 69: 616–620, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowalewska J, Tomford RC, Alpers CE: Crystals in podocytes: An unusual manifestation of systemic disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 605–611, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta V, El Ters M, Kashani K, Leung N, Nasr SH: Crystalglobulin-induced nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 525–529, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocca A, Khamlichi AA, Touchard G, Mougenot B, Ronco P, Denoroy L, Deret S, Preud’homme JL, Aucouturier P, Cogné M: Sequences of V kappa L subgroup light chains in Fanconi’s syndrome. Light chain V region gene usage restriction and peculiarities in myeloma-associated Fanconi’s syndrome. J Immunol 155: 3245–3252, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aucouturier P, Bauwens M, Khamlichi AA, Denoroy L, Spinelli S, Touchard G, Preud’homme JL, Cogné M: Monoclonal Ig L chain and L chain V domain fragment crystallization in myeloma-associated Fanconi’s syndrome. J Immunol 150: 3561–3568, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leboulleux M, Lelongt B, Mougenot B, Touchard G, Makdassi R, Rocca A, Noel LH, Ronco PM, Aucouturier P: Protease resistance and binding of Ig light chains in myeloma-associated tubulopathies. Kidney Int 48: 72–79, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders PW: Mechanisms of light chain injury along the tubular nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1777–1781, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen CP, Bell JM, Harris AA, Messias NC, Wang YH, Walker PD: The morphologic spectrum and clinical significance of light chain proximal tubulopathy with and without crystal formation. Mod Pathol 24: 1462–1469, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapur U, Barton K, Fresco R, Leehey DJ, Picken MM: Expanding the pathologic spectrum of immunoglobulin light chain proximal tubulopathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 131: 1368–1372, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrera GA: Proximal tubulopathies associated with monoclonal light chains: The spectrum of clinicopathologic manifestations and molecular pathogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138: 1365–1380, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Déret S, Denoroy L, Lamarine M, Vidal R, Mougenot B, Frangione B, Stevens FJ, Ronco PM, Aucouturier P: Kappa light chain-associated Fanconi’s syndrome: Molecular analysis of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains from patients with and without intracellular crystals. Protein Eng 12: 363–369, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fermand JP, Bridoux F, Kyle RA, Kastritis E, Weiss BM, Cook MA, Drayson MT, Dispenzieri A, Leung N; International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group : How I treat monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS). Blood 122: 3583–3590, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duquesne A, Werbrouck A, Fabiani B, Denoyer A, Cervera P, Verpont MC, Bender S, Piedagnel R, Brocheriou I, Ronco P, Boffa JJ, Aucouturier P, Garderet L: Complete remission of monoclonal gammopathy with ocular and periorbital crystal storing histiocytosis and Fanconi syndrome. Hum Pathol 44: 927–933, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishida Y, Iwama K, Yamakura M, Takeuchi M, Matsue K: Renal Fanconi syndrome as a cause of chronic kidney disease in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: Partially reversed renal function by high-dose dexamethasone with bortezomib. Leuk Lymphoma 53: 1804–1806, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasr SH, Galgano SJ, Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD: Immunofluorescence on pronase-digested paraffin sections: A valuable salvage technique for renal biopsies. Kidney Int 70: 2148–2151, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV: Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia 23: 3–9, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Bladé J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, Gertz M, Dimopoulos M, Westin J, Sonneveld P, Ludwig H, Gahrton G, Beksac M, Crowley J, Belch A, Boccadaro M, Cavo M, Turesson I, Joshua D, Vesole D, Kyle R, Alexanian R, Tricot G, Attal M, Merlini G, Powles R, Richardson P, Shimizu K, Tosi P, Morgan G, Rajkumar SV; International Myeloma Working Group : International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 20: 1467–1473, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.