Abstract

The complement–mediated renal diseases C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) strongly associate with inherited and acquired abnormalities in the regulation of the complement alternative pathway (AP). The major negative regulator of the AP is the plasma protein complement factor H (FH). Abnormalities in FH result in uncontrolled activation of C3 through the AP and associate with susceptibility to both C3G and aHUS. Although previously developed FH–deficient animal models have provided important insights into the mechanisms underlying susceptibility to these unique phenotypes, these models do not entirely reproduce the clinical observations. FH is predominantly synthesized in the liver. We generated mice with hepatocyte–specific FH deficiency and showed that these animals have reduced plasma FH levels with secondary reduction in plasma C3. Unlike mice with complete FH deficiency, hepatocyte–specific FH–deficient animals developed neither plasma C5 depletion nor accumulation of C3 along the glomerular basement membrane. In contrast, subtotal FH deficiency associated with mesangial C3 accumulation consistent with C3G. Although there was no evidence of spontaneous thrombotic microangiopathy, the hepatocyte–specific FH–deficient animals developed severe C5–dependent thrombotic microangiopathy after induction of complement activation within the kidney by accelerated serum nephrotoxic nephritis. Taken together, our data indicate that subtotal FH deficiency can give rise to either spontaneous C3G or aHUS after a complement-activating trigger within the kidney and that the latter is C5 dependent.

Keywords: complement, GN, immunology, thrombosis, transgenic mouse

Both atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) and C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) can develop in the setting of abnormal complement regulation.1–3 C3G includes the entities dense deposit disease and C3 GN and is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of C3 within the glomerulus, which may or may not be associated with inflammation, such as membranoproliferative GN (MPGN).4 In practice, it is considered when there is C3-dominant GN, with dominance defined as C3 reactivity at least two orders of magnitude more intense than any other immune reactant.5 In aHUS, there is complement-mediated damage to the renal endothelium with consequent development of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).2

C3G and aHUS are typically associated with genetic and acquired abnormalities that result in uncontrolled activation of the complement alternative pathway (AP). Complement factor H (FH) is the major negative regulator of the AP, and abnormalities in FH have been associated with aHUS and C3G.3 Genetic changes in complement components in aHUS include loss of function in regulators (FH, complement factor I [FI], and CD46) and gain of function in activation proteins (complement factor B and C3).2 In C3G, genetic abnormalities are less frequent and include loss-of-function changes in FH, gain-of-function change in C3, and structural changes within the FH–like gene family.1 Acquired factors include autoantibodies that enhance AP activation (most commonly C3 nephritic factors in the case of C3G and anti-FH autoantibodies in aHUS).1,2

Intriguingly, case reports have shown that complete FH deficiency can manifest as aHUS or C3G.3 The factors that determine which pathology develops in the setting of FH deficiency are not fully understood, but mechanistic insights into C3G and aHUS have derived from functional characterization of the genetic defects together with the study of animal models that mimic some of these defects.3,6 Pigs7 and mice8 with complete FH deficiency develop spontaneous C3G but not aHUS. In both species, the deficiency results in uncontrolled AP activation and secondary consumption of C33 and C5,7,9 which results in absence of plasma complement hemolytic activity. In FH-deficient (Cfh−/−) mice, spontaneous C3G depended on AP activation8 but not on C510 and developed in wild-type kidneys transplanted into Cfh−/− recipients.11 Notably, spontaneous C3G did not develop in the heterozygous FH–deficient pig or mouse strain.7,8 FH consists of 20 short consensus repeat (SCR) domains, with SCR1 to -4 essential for C3 regulation and SCR19 and SCR20 important in interacting with surface polyanions and C3b. FH mutations in aHUS predominantly affect the surface recognition sites within SCR19 and SCR20.6 C5–dependent spontaneous aHUS did occur in Cfh−/− mice transgenic for an FH protein (FHΔ16–20) that lacked surface recognition domains.9,12 This led to the paradigm that aHUS occurs when there is a combination of defective regulation of complement activation along the glomerular endothelium (e.g., in the presence of FH mutations that impair surface recognition) and sufficient circulating intact C3 and C5 to enable complement–mediated endothelial injury to occur.9,12

Here, we report the phenotype of hepatocyte–specific FH–deficient (hepatocyte-Cfh−/−) mice and show that this strain has plasma FH levels of approximately 20% of normal. This subtotal FH deficiency resulted in plasma C3 dysregulation and accumulation of C3 within mesangial areas. However, unlike mice with total FH deficiency, hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice did not develop plasma C5 deficiency or glomerular basement membrane (GBM) C3 deposition. The hepatocyte-Cfh−/− animals did not develop spontaneous aHUS, but after experimentally triggered renal injury using accelerated serum nephrotoxic nephritis (NTN), they developed a severe C5–dependent TMA.

Results

Hepatocyte-Cfh−/− Mice Have Reduced Plasma FH and C3 but Normal Plasma C5

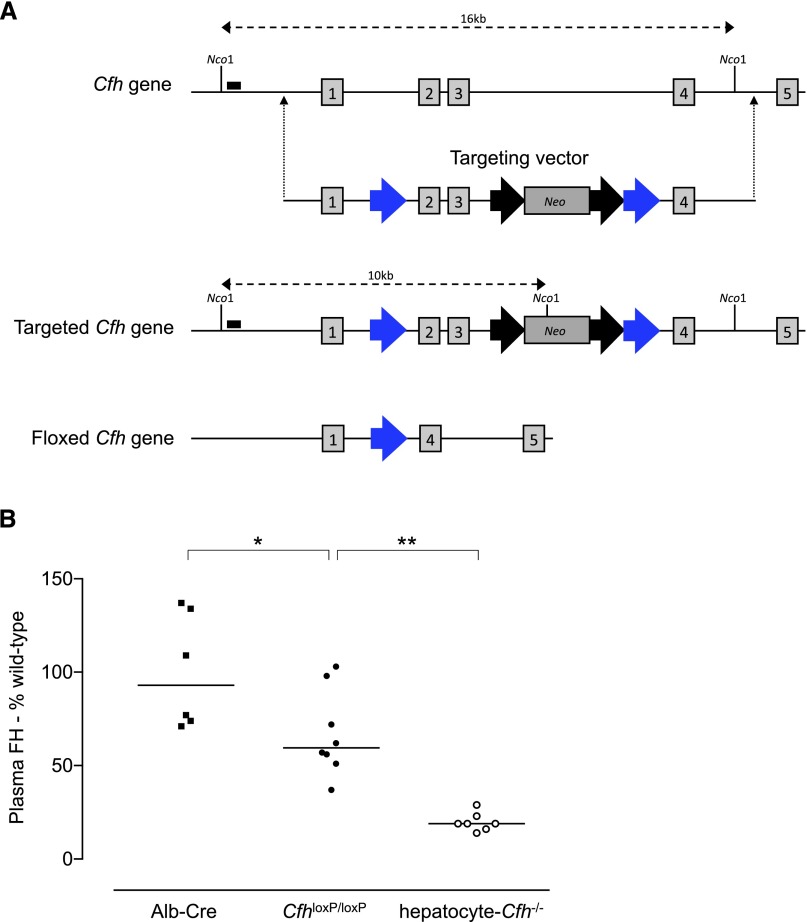

The conditional FH–deficient (CfhloxP/loxP) strain was developed using recombineering techniques13 to introduce loxP sites on either side of exons 2 and 3 of the Cfh gene in embryonic stem cells (Figure 1A). CfhloxP/loxP mice were viable and backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 genetic background. To generate hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice, the CfhloxP/loxP strain was intercrossed with mice selectively expressing Cre recombinase in hepatocytes using the albumin promoter/enhancer sequence (Alb-Cre).14 Hepatocyte Cre recombinase–mediated excision of exons 2 and 3 was confirmed by analysis of hepatic RNA (Supplemental Figure 1). Consistent with hepatocytes being the predominant source of plasma FH, circulating FH levels were significantly reduced in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice (Figure 1B). This subtotal FH deficiency was associated with marked reduction in plasma C3 levels, although not as low as that seen in mice with complete FH deficiency (Figure 2A). However, unlike Cfh−/− mice, plasma C5 levels appeared normal when assessed semiquantitatively by Western blotting (Figure 2B). Unexpectedly, CfhloxP/loxP animals had significantly lower plasma FH and C3 compared with Alb-Cre mice (Figures 1B and 2A). This indicated that the production of FH from the targeted cfh allele was impaired.

Figure 1.

Generation of the conditional FH–deficient mouse. (A) The targeting vector contained loxP sites (blue arrows) located on either side of exons 2 and 3 of the Cfh gene. The targeted locus contained a neomycin–resistant (Neo) positive selectable marker flanked by flippase recombinase recognition target sites (black arrows). Cre recombinase–mediated recombination between the loxP sites results in excision of exons 2 and 3 and the positive selectable marker (floxed allele). This causes a reading frameshift, generation of a premature stop codon in exon 4, and therefore, a null allele. Vertical numbered boxes denote exons. Nco1 is a restriction enzyme. Black boxes denote probe locations used to identify correctly targeted cells. (B) Plasma FH levels in 12-week-old Alb-Cre (median=93% of wild-type levels; range=71%–137%; n=6), CfhloxP/loxP (median=59.5% of wild-type levels; range=37%–103%; n=8), and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− (median=19% of wild-type levels; range=14%–29%; n=7) mice. Horizontal bars denote median values. P values are derived from Bonferroni multiple comparison test. *P=0.03; **P=0.002.

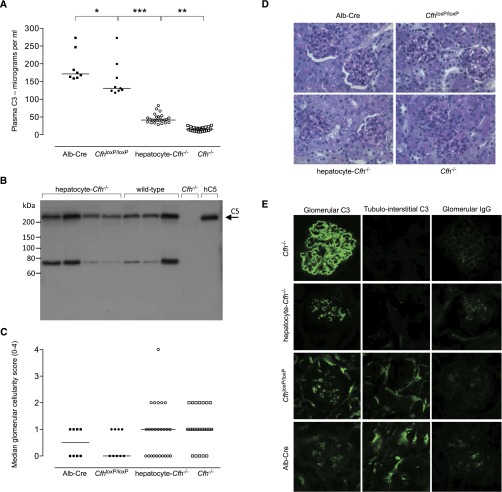

Figure 2.

Plasma complement and spontaneous renal phenotype in conditional and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. (A) Plasma C3 levels in 9-month-old Alb-Cre (median=171.5 µg/ml; range=158.8–273.1; n=8), CfhloxP/loxP (median=131.1 µg/ml; range=118.4–272.8; n=9), hepatocyte-Cfh−/− (median=41.5 µg/ml; range=28.6–82.2; n=25), and Cfh−/− (median=15.8 µg/ml; range=7.9–26.6; n=23) mice. Horizontal bars denote median values. P values are derived from Bonferroni multiple comparison test. *P<0.05; **P<0.001; ***P<0.001. (B) Assessment of plasma C5 in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice by Western blotting. The intensity of the C5 protein band was comparable between hepatocyte-Cfh−/− (lanes 1–4) and wild-type (lanes 5–7) mice. No C5 is seen in Cfh−/− plasma (lane 8), and lane 9 contained 100 ng purified human C5 as reference. (C) Glomerular cellularity scores and (D) representative PAS–stained glomerular images in 9-month-old Alb-Cre, CfhloxP/loxP, hepatocyte-Cfh−/−, and Cfh−/− mice. Horizontal bars denote median values. Original magnification, ×40. (E) Representative immunostaining images for glomerular C3 and IgG in 9-month-old Alb-Cre, CfhloxP/loxP, hepatocyte-Cfh−/−, and Cfh−/− mice. The characteristic linear capillary wall C3 deposition seen in Cfh−/− mice was replaced by a mesangial staining pattern in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. Tubulointerstitial C3 deposition was absent in Cfh−/− mice and normal in CfhloxP/loxP and Alb-Cre animals. It was detectable but reduced in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. Mesangial IgG is commonly seen in older mice and was detectable in small amounts in all of the cohorts.

Hepatocyte-Cfh−/− Mice Develop Spontaneous Mesangial but Not GBM C3 Deposition

Cfh−/− mice spontaneously develop C3 accumulation along the GBM.8 To determine if subtotal FH deficiency was associated with the same renal phenotype, we examined renal histology in 9-month-old hepatocyte-Cfh−/− and Cfh−/− mice. We included CfhloxP/loxP and Alb-Cre strains as control groups (Supplemental Table 1). We found that serum urea levels were <20 mmol/L, with the exceptions of the levels in one animal in the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− cohort (26.5 mmol/L) and two animals in the Cfh−/− cohort (20.5 and 21.7 mmol/L). Albuminuria was only detectable in one of the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− (2.1 mg/ml) mice. Hematocrits and peripheral blood smears were normal (Supplemental Figure 2). Renal light microscopy showed minimal glomerular hypercellularity in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− and Cfh−/− mice and no evidence of glomerular thrombosis (Figure 2, C and D). As expected, all Cfh−/− mice had linear glomerular capillary wall C3 staining.8 In contrast, glomerular C3 deposition was granular and mesangial in distribution in age–matched hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice (Figure 2E). The normal tubulointerstitial C3 staining pattern (seen in the control strains) (Figure 2E) was reduced in intensity in the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− strain and as previously shown,8 absent in Cfh−/− animals. These data indicated that subtotal FH deficiency was sufficient to prevent C3 accumulation along the GBM.

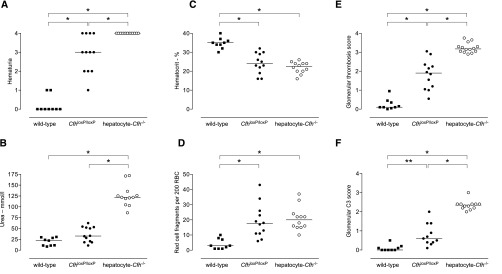

Hepatocyte-Cfh−/− and CfhloxP/loxP Mice Develop TMA during NTN

To test the hypothesis that the impaired complement regulation associated with subtotal FH deficiency predisposed to enhanced renal damage during complement activation within the glomerulus, we examined the response of hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice to NTN. Hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice rapidly developed renal failure, and animals were humanely culled on day 3 after administration of nephrotoxic serum (NTS) (Figure 3). In a representative experiment, 2 of 14 hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice were culled 3 days after receiving NTS, whereas there were no deaths in the wild-type (n=9) and CfhloxP/loxP (n=12) groups. Maximal hematuria developed in all hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice 1 day post-NTS (Supplemental Figure 3). Compared with wild-type mice, at day 3 post-NTS, hepatocyte-Cfh−/− animals had greater hematuria, higher urea levels, lower hematocrits, marked red cell fragmentation, and glomerular thrombosis (Figures 3 and 4). Glomerular C3 was highest in the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice (Figure 3F). Differences in glomerular IgG and sheep IgG were minimal, and the immune response to sheep IgG in adjuvant was equivalent between the experimental groups (Supplemental Figures 4–6). CfhloxP/loxP mice, in which we had shown slight reduction in plasma FH levels (Figure 1B), developed a phenotype intermediate in severity between those of wild-type and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. Together, these data indicated that subtotal FH deficiency was associated with a hypersensitive response during NTN and that the severity of TMA was related to the degree of FH deficiency.

Figure 3.

Response of conditional and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice to accelerated serum NTN. (A) Hematuria, (B) serum urea, (C) hematocrit, (D) red cell fragments, (E) glomerular thrombosis score, and (F) glomerular C3 deposition at day 3 after administration of NTS to preimmunized wild–type, CfhloxP/loxP, and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. Horizontal bars denote median values. Data are representative of three independent experiments. P values are derived from Bonferroni multiple comparison test. *P<0.001; **P<0.01. RBC, red blood cell.

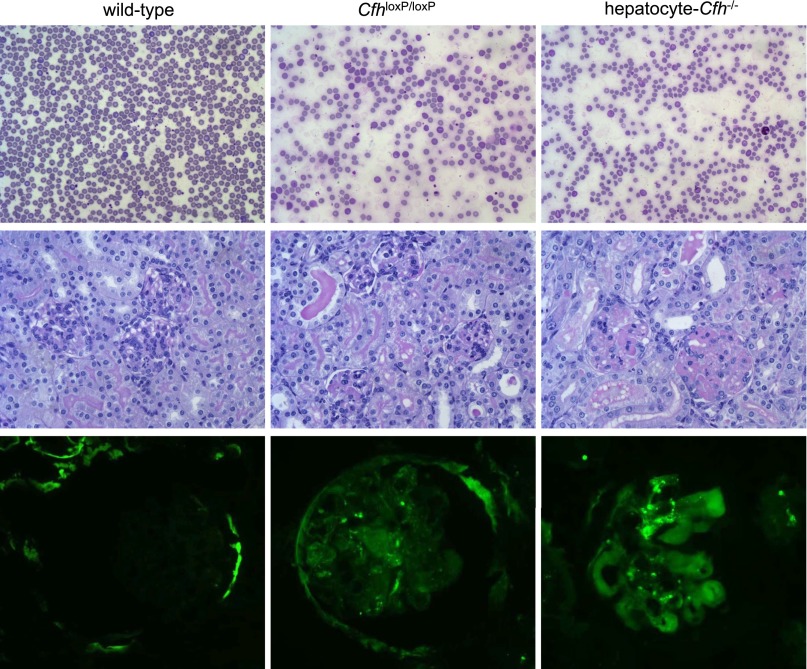

Figure 4.

Response of conditional and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice to accelerated serum NTN. Representative images of (top panel) peripheral blood smears, (middle panel) renal sections, and (bottom panel) glomerular C3 immunostaining in wild-type, CfhloxP/loxP, and hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice.

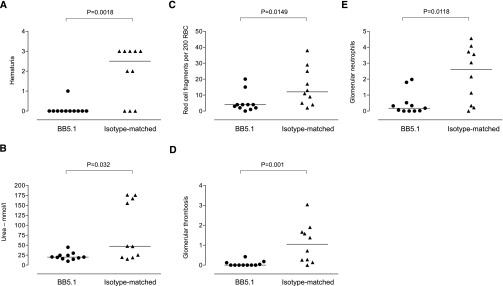

The Hypersensitive Response of Hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice during NTN Is Dependent on C5

Because hepatocyte-Cfh−/− animals had normal C5 levels, we hypothesized that the enhanced renal damage during NTN could be influenced by C5 activation. To test this hypothesis, we administered either a monoclonal anti–mouse C5 antibody (BB5.1) or an isotype–matched control antibody to hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. Administration of BB5.1 ameliorated the renal damage, with reduced hematuria, urea, red cell fragmentation, and glomerular thrombosis and neutrophil scores (Figure 5). Notably, the thrombosis was lower in the isotype–matched antibody–treated group than that typically seen in untreated hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice during NTN (Figure 3E). These data indicated that the hypersensitive response of hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice during NTN was dependent on C5.

Figure 5.

Antibody–mediated C5 inhibition in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice during accelerated serum NTN. (A) Hematuria, (B) serum urea, (C) red cell fragments, (D) glomerular thrombosis score, and (E) glomerular neutrophil numbers at day 4 after administration of NTS to preimmunized hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice treated with either BB5.1 (n=11) or isotype-matched antibody (n=10). Horizontal bars denote median values. P values were derived from Mann–Whitney test. RBC, red blood cell.

Discussion

Mice with hepatocyte-specific FH deficiency were established by intercrossing conditional FH–deficient mice with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of a hepatocyte-specific promoter. The hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice had low plasma FH and C3 levels and spontaneous development of mesangial C3 deposition. This type of lesion has been reported as one morphologic type of human C3G.15 Heterozygous FH–deficient animals have normal glomerular C3 staining pattern with slight but significantly lower plasma C3 levels than wild-type mice.8 The FH levels in the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice (approximately 20% of normal) were lower than those in heterozygous FH–deficient mice12 but still sufficient to prevent glomerular C3 accumulation along the GBM, a characteristic feature of mice with complete FH deficiency.8 However, the subtotal FH level in the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice resulted in spontaneous mesangial C3 deposition. Paramesangial deposits composed solely of C3c have been reported in dense deposit disease specifically during episodes of hypocomplementemia.16 It was hypothesized that they were derived from plasma C3c that had been released after the FI-mediated cleavage of iC3b to C3dg. This mechanism could be operating in the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice continuously because of the low FH levels. The normal tubulointerstitial C3 staining seen in wild-type mice was reduced in intensity in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice. This is most likely caused by the reduced plasma C3 levels, because tubulointerstitial C3 staining in mice is dependent on circulating C3.11,17,18

Renal disease in C3G may become clinically evident or be exacerbated by an environmental trigger, such as infection. For example, upper respiratory tract infection is an exacerbating factor in IgA nephropathy (synpharyngitic macroscopic hematuria) and C3G.19,20 The hypothesis is that the inability to regulate the AP not only increases susceptibility to spontaneous C3G but also, increases the likelihood of renal injury during an intercurrent event that triggers complement activation within the kidney. To model this, we examined the response of hepatocyte-Cfh−/− animals to NTN. Our observations showed that partial FH deficiency enhanced renal injury during experimental NTN and that this was C5 dependent. Hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice were extremely sensitive to renal injury in this model and developed a renal phenotype consistent with aHUS. Our interpretation is that hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice were susceptible during NTN because of a combination of the inability of the partial FH deficiency to adequately regulate complement within the kidney and the ability of the partial FH deficiency to preserve sufficient C5 in plasma to mediate injury. The hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice were housed in specific pathogen–free conditions, so we do not know how the renal phenotype might be influenced by infection. The C5 dependence of the TMA in our experimental model suggests that the therapeutic use of C5 inhibition in C3G may be particularly useful in patients with C3G and defective complement regulation who present with features of intercurrent TMA.

The spontaneous phenotype (mesangial C3G with no evidence of TMA) and the phenotype observed during NTN (acute severe TMA) were distinct. There is clear evidence of phenotypic variation within these diseases among individuals with the same complement mutation. For example, in complement factor H-related protein 5 nephropathy, the spectrum of renal disease varies from microscopic hematuria to end stage renal failure.21 Similarly, in aHUS, incomplete penetrance in the setting of complement mutations is common, and clinical onset is typically preceded by an environmental change (e.g., infection, drugs, and pregnancy).22 However, variation between C3G and aHUS phenotypes within the same individual is less well understood. Patient reports of C3G as the presenting feature with aHUS occurring later in the clinical course include an adult man with complete FH deficiency who presented with biopsy-proven C3G (MPGN) but approximately 1 year later, developed aHUS23; an individual with anti-FH autoantibodies who presented with C3G (MPGN) and developed recurrent C3G in the first renal transplant and TMA in the second transplant24; a young man with mutations in both C3 and CD46 and a family history of aHUS who presented initially with C3G (MPGN) before developing clinical features of aHUS25; a young man with a heterozygous FH mutation who presented with C3G (MPGN) and later developed aHUS26,27; an adult woman with C3G (MPGN) with no complement mutations who later developed aHUS27; and an adult man with C3G (mesangial C3 deposits) with no complement mutations who later developed concurrent aHUS.27 Patient reports of aHUS as the presenting feature with C3G occurring later in the clinical course are less numerous but include a young man with combined heterozygous FH and FI mutations who presented with aHUS and subsequently developed glomerular C3 deposits in the transplant kidney28 and a young man with homozygous FH deficiency who presented with aHUS and then developed isolated glomerular C3 deposits in the absence of TMA within the transplant kidney.28 In this context, the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mice recapitulate the clinical observations and provide definitive experimental evidence that the same genetic defect can predispose to C3G and aHUS.

The mice carrying the targeted Cfh alleles had significantly reduced basal plasma FH and C3 levels, indicating that expression of FH by the targeted locus was impaired. These animals were also hypersensitive to renal injury during NTN, which on the basis of the hepatocyte-Cfh−/− NTN phenotype, was likely a consequence of the reduced FH levels. Impaired expression of targeted genes because of the introduction of loxP sites and/or selectable markers is well recognized and may be rectified by removal of the selectable marker.29 In our construct, flippase recombinase recognition target sites were placed on either side of the neomycin resistance gene to enable the neomycin resistance gene to be excised by flippase recombinase, and this is currently in progress. With this dataset, the impaired FH expression from the targeted allele prevented us from deriving any firm conclusions with respect to the contribution of extrahepatocyte FH to the total FH pool.

In summary, our experimental data showed that two distinct renal phenotypes, C3G and aHUS, can develop in the setting of subtotal FH deficiency. Like spontaneous aHUS in a murine model of FH-associated aHUS,9 experimentally triggered aHUS in hepatocyte-Cfh−/− animals was C5 dependent, further supporting the key role of C5 in complement–mediated glomerular TMA. Our data illustrate the complex relationship between FH insufficiency and complement–mediated renal injury and that the therapeutic use of C5 inhibition in this setting depends on the renal phenotype.

Concise Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in specific pathogen–free conditions, and all animal procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the United Kingdom Government. Recombineering reagents, EL350 cells, PL451 plasmid, and PL452 plasmid were obtained from the National Cancer Institute at Frederick (www.ncifrederick.cancer.gov). Mice used in models of experimental renal disease were matched for age and sex and between 10 and 12 weeks of age at the time of the experiment. Alb-Cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (B6.Cg-Tg[Alb-cre]21Mgn/J; strain no. 003574; http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/003574.html). Genotyping was performed by PCR on digested tissue using primers pairs. Alb-Cre primer pairs 5′- GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC-3′ and 5′-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3′ generated a 100-bp product in the presence of the Alb-Cre allele. Targeted Cfh allele primer pairs 5′-AGGGGGAAAGAGAGAGATG-3 and 5′-TCCTAGTAGCAAAGCTAAACAG-3′ generated a 450- or 527-bp amplicon in wild-type and targeted Cfh alleles, respectively. Floxed Cfh allele primer pairs 5′-CTGTCAGCAAGAATTATTTGGC-3′ and 5′-ACACATCGTGGCTTTTCATTGC-3′ generated a 610- or 318-bp amplicon in wild-type and floxed Cfh alleles, respectively. The 9-month-old cohorts were comprised of hepatocyte-Cfh−/− (n=25; 12 males and 13 females), Cfh−/− (n=23; 8 males and 15 females), CfhloxP/loxP (n=9; 4 males and 5 females), and Alb-Cre (n=8; 2 males and 6 females) mice. Two unexplained deaths occurred: one hepatocyte-Cfh−/− mouse aged 5 weeks old and one Alb-Cre mouse aged 17 weeks old. In both cases, renal histology was normal by light microscopy.

Measurement and Detection of Mouse FH, C3, and C5

Mouse blood samples were collected directly into EDTA–containing Eppendorf tubes and kept on ice until centrifugation, and aliquots were stored at −80°C. Repeated freeze/thaw cycles were avoided. Plasma FH levels were measured by ELISA using a polyclonal sheep anti–human FH antibody (antibodies-online.com) and a biotinylated goat anti–human FH antibody (Quidel, San Diego, CA). FH levels in the samples were quantified relative to the normal wild–type mouse plasma used in the standard curve. Measurement of plasma C3 was performed by ELISA as previously described30 using unconjugated and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated polyclonal goat anti–mouse C3 antibodies (MP Biomedical, Cambridge, UK), with a standard curve generated using acute-phase serum containing a known quantity of C3 (Calbiochem, Hertfordshire, UK). Western blotting for mouse C5 was performed as previously described.31

Assessment of Renal and Hematologic Function

Hematuria was detected using Hema-Combistix Urine Reagent Strips (Siemens, Frimley, UK) using the following scale: negative, trace, 1+, 2+, and 3+. Plasma urea was measured using an ultraviolet method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R-Biopharm, Glasgow, UK). Plasma samples were diluted 1:40 in PBS, and a standard preparation of urea of known concentration was included as an internal control. Albuminuria was measured using radial immunodiffusion as previously described10 with a rabbit anti–mouse albumin antibody (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) and purified mouse albumin standard (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK). Hematocrit was calculated after centrifuging EDTA-treated blood in ammonium-heparin capillary tubes (VWR International Ltd., Lutterworth, UK) at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes and measuring the packed cell height to total height ratio. Peripheral blood smears were prepared on glass slides and stained using the Diff Quick Staining Kit (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA). Red cell fragments were quantified as the number per 200 red blood cells counted at high power (×40).

Assessment of Renal Histology

Kidneys were fixed in Bouin’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2–4 hours and then transferred to 70% ethanol. Sections were embedded in paraffin, stained with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reagent, and examined by light microscopy. Sections were scored for glomerular thrombosis and glomerular neutrophil infiltration. Analyses were all done blinded to the sample identity, with 20 glomeruli scored per section. Glomerular thrombosis was scored according to the amount of PAS-positive material per glomerular cross-section as follows: grade 0, no PAS-positive material; grade 1, 0%–25%; grade 2, 25%–50%; grade 3, 50%–75%; and grade 4, 75%–100%. Glomerular neutrophils were scored according to the number of neutrophils per glomerular cross-section. Glomerular histology was graded as follows: grade 0, normal; grade 1, segmental hypercellularity in 10%–25% of the glomeruli; grade 2, hypercellularity involving >50% of the glomerular tuft in 25%–50% of glomeruli; grade 3, hypercellularity involving >50% of the glomerular tuft in 50%–75% of glomeruli; and grade 4, glomerular hypercellularity in >75% or crescents in >25% of glomeruli. Immunostaining for C3, IgG, and sheep IgG was performed on acetone–dried 5-µm frozen sections as previously described.32 Antibodies used were FITC–labeled polyclonal goat anti–mouse C3 (MP Biomedical), FITC–conjugated polyclonal goat anti–mouse IgG Fc γ-chain–specific antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and an FITC–conjugated monoclonal mouse anti–goat/sheep IgG (Sigma-Aldrich). Quantitative immunofluorescence analysis was performed using an Olympus fluorescent microscope with digital camera (Olympus, Southend, UK) and Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD), and a minimum of 10 glomeruli were examined per section as previously described.32 Mean fluorescence intensity was expressed in arbitrary fluorescence units. Glomerular C3 from NTN was scored according to the number of glomerular cross–section quadrants that stained for C3. Grades 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent staining of zero, one, one to two, two to three, or all four quadrants, respectively.

Induction of Serum NTN

NTN was induced by the intravenous injection of 200 μl sheep NTS (a sheep IgG serum fraction containing anti–mouse GBM antibodies) into mice that had been preimmunized with an intraperitoneal injection of 200 µg sheep IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) in CFA (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described.32 For anti–C5 antibody treatment, mice received either 2 mg BB5.1 or isotype-matched antibody subcutaneously 24 hours before NTS. The animals received two more doses of either BB5.1 or isotype-matched antibody on days 1 and 3 post-NTS administration. To assess the immune response to sheep IgG, hepatocyte-Cfh−/− (n=8), CfhloxP/loxP (n=7), and wild-type (n=10) mice were injected with 200 µg sheep IgG in CFA. Plasma samples were collected on days 2, 4, and 9 postimmunization. IgG response to sheep IgG was measured by ELISA on microtiter plates coated with 3.5 µg/ml sheep IgG. The plates were incubated with mouse plasma serially diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA. Bound mouse IgG was detected with a peroxidase–conjugated sheep anti–mouse IgG antibody (Jackson Immune Research). The antibody titer was expressed as the inverse of the greatest serum dilution that gave 2-fold background reading.

Statistical Analyses

Nonparametric data were represented as medians, with the ranges of values given in parentheses. Two groups were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test, whereas one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to analyze three or more groups. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 3.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

Disclosures

M.C.P. has received fees from Alexion Pharmaceuticals for invited lectures and preclinical testing of complement therapeutics and consultancy fees from Achillion Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

K.A.V. was funded by Kidney Research United Kingdom Clinical Fellowship TF8/2009. M.M.R. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Fellowship. M.C.P. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science (Fellowship WT082291MA).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015030295/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Barbour TD, Ruseva MM, Pickering MC: Update on C3 glomerulopathy [published online ahead of print October 17, 2014]. Nephrol Dial Transplant doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Le Quintrec M, Roumenina L, Noris M, Frémeaux-Bacchi V: Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with mutations in complement regulator genes. Semin Thromb Hemost 36: 641–652, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickering MC, Cook HT: Translational mini-review series on complement factor H: Renal diseases associated with complement factor H: Novel insights from humans and animals. Clin Exp Immunol 151: 210–230, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickering MC, D’Agati VD, Nester CM, Smith RJ, Haas M, Appel GB, Alpers CE, Bajema IM, Bedrosian C, Braun M, Doyle M, Fakhouri F, Fervenza FC, Fogo AB, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Gale DP, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Griffin G, Harris CL, Holers VM, Johnson S, Lavin PJ, Medjeral-Thomas N, Paul Morgan B, Nast CC, Noel LH, Peters DK, Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Servais A, Sethi S, Song WC, Tamburini P, Thurman JM, Zavros M, Cook HT: C3 glomerulopathy: Consensus report. Kidney Int 84: 1079–1089, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou J, Markowitz GS, Bomback AS, Appel GB, Herlitz LC, Barry Stokes M, D’Agati VD: Toward a working definition of C3 glomerulopathy by immunofluorescence. Kidney Int 85: 450–456, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Córdoba SR, de Jorge EG: Translational mini-review series on complement factor H: Genetics and disease associations of human complement factor H. Clin Exp Immunol 151: 1–13, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høgåsen K, Jansen JH, Mollnes TE, Hovdenes J, Harboe M: Hereditary porcine membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type II is caused by factor H deficiency. J Clin Invest 95: 1054–1061, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickering MC, Cook HT, Warren J, Bygrave AE, Moss J, Walport MJ, Botto M: Uncontrolled C3 activation causes membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in mice deficient in complement factor H. Nat Genet 31: 424–428, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jorge EG, Macor P, Paixão-Cavalcante D, Rose KL, Tedesco F, Cook HT, Botto M, Pickering MC: The development of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome depends on complement C5. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 137–145, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering MC, Warren J, Rose KL, Carlucci F, Wang Y, Walport MJ, Cook HT, Botto M: Prevention of C5 activation ameliorates spontaneous and experimental glomerulonephritis in factor H-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 9649–9654, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander JJ, Wang Y, Chang A, Jacob A, Minto AW, Karmegam M, Haas M, Quigg RJ: Mouse podocyte complement factor H: The functional analog to human complement receptor 1. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1157–1166, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickering MC, de Jorge EG, Martinez-Barricarte R, Recalde S, Garcia-Layana A, Rose KL, Moss J, Walport MJ, Cook HT, de Córdoba SR, Botto M: Spontaneous hemolytic uremic syndrome triggered by complement factor H lacking surface recognition domains. J Exp Med 204: 1249–1256, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG: A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res 13: 476–484, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Postic C, Shiota M, Niswender KD, Jetton TL, Chen Y, Moates JM, Shelton KD, Lindner J, Cherrington AD, Magnuson MA: Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic beta cell-specific gene knock-outs using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem 274: 305–315, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Servais A, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Lequintrec M, Salomon R, Blouin J, Knebelmann B, Grünfeld JP, Lesavre P, Noël LH, Fakhouri F: Primary glomerulonephritis with isolated C3 deposits: A new entity which shares common genetic risk factors with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Med Genet 44: 193–199, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West CD, Witte DP, McAdams AJ: Composition of nephritic factor-generated glomerular deposits in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type 2. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 1120–1130, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paixão-Cavalcante D, Hanson S, Botto M, Cook HT, Pickering MC: Factor H facilitates the clearance of GBM bound iC3b by controlling C3 activation in fluid phase. Mol Immunol 46: 1942–1950, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenderink AM, Liegel K, Ljubanović D, Coleman KE, Gilkeson GS, Holers VM, Thurman JM: The alternative pathway of complement is activated in the glomeruli and tubulointerstitium of mice with adriamycin nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F555–F564, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gale DP, de Jorge EG, Cook HT, Martinez-Barricarte R, Hadjisavvas A, McLean AG, Pusey CD, Pierides A, Kyriacou K, Athanasiou Y, Voskarides K, Deltas C, Palmer A, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, de Cordoba SR, Maxwell PH, Pickering MC: Identification of a mutation in complement factor H-related protein 5 in patients of Cypriot origin with glomerulonephritis. Lancet 376: 794–801, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernon KA, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Hall AE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Aitman TJ, Cook HT, Hangartner R, Koziell A, Pickering MC: Acute presentation and persistent glomerulonephritis following streptococcal infection in a patient with heterozygous complement factor H-related protein 5 deficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 121–125, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Athanasiou Y, Voskarides K, Gale DP, Damianou L, Patsias C, Zavros M, Maxwell PH, Cook HT, Demosthenous P, Hadjisavvas A, Kyriacou K, Zouvani I, Pierides A, Deltas C: Familial C3 glomerulopathy associated with CFHR5 mutations: Clinical characteristics of 91 patients in 16 pedigrees. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1436–1446, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caprioli J, Castelletti F, Bucchioni S, Bettinaglio P, Bresin E, Pianetti G, Gamba S, Brioschi S, Daina E, Remuzzi G, Noris M; International Registry of Recurrent and Familial HUS/TTP : Complement factor H mutations and gene polymorphisms in haemolytic uraemic syndrome: The C-257T, the A2089G and the G2881T polymorphisms are strongly associated with the disease. Hum Mol Genet 12: 3385–3395, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaziri-Sani F, Holmberg L, Sjöholm AG, Kristoffersson AC, Manea M, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Fehrman-Ekholm I, Raafat R, Karpman D: Phenotypic expression of factor H mutations in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int 69: 981–988, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorcy N, Rioux-Leclercq N, Lombard ML, Le Pogamp P, Vigneau C: Three kidneys, two diseases, one antibody? Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3811–3813, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brackman D, Sartz L, Leh S, Kristoffersson AC, Bjerre A, Tati R, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Karpman D: Thrombotic microangiopathy mimicking membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3399–3403, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gnappi E, Allinovi M, Vaglio A, Bresin E, Sorosina A, Pilato FP, Allegri L, Manenti L: Membrano-proliferative glomerulonephritis, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, and a new complement factor H mutation: Report of a case. Pediatr Nephrol 27: 1995–1999, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manenti L, Gnappi E, Vaglio A, Allegri L, Noris M, Bresin E, Pilato FP, Valoti E, Pasquali S, Buzio C: Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome with underlying glomerulopathies. A case series and a review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2246–2259, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyer O, Noël LH, Balzamo E, Guest G, Biebuyck N, Charbit M, Salomon R, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Niaudet P: Complement factor H deficiency and posttransplantation glomerulonephritis with isolated C3 deposits. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 671–677, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiering S, Epner E, Robinson K, Zhuang Y, Telling A, Hu M, Martin DI, Enver T, Ley TJ, Groudine M: Targeted deletion of 5'HS2 of the murine beta-globin LCR reveals that it is not essential for proper regulation of the beta-globin locus. Genes Dev 9: 2203–2213, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose KL, Paixao-Cavalcante D, Fish J, Manderson AP, Malik TH, Bygrave AE, Lin T, Sacks SH, Walport MJ, Cook HT, Botto M, Pickering MC: Factor I is required for the development of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in factor H-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 118: 608–618, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruseva MM, Vernon KA, Lesher AM, Schwaeble WJ, Ali YM, Botto M, Cook T, Song W, Stover CM, Pickering MC: Loss of properdin exacerbates C3 glomerulopathy resulting from factor H deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 43–52, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robson MG, Cook HT, Botto M, Taylor PR, Busso N, Salvi R, Pusey CD, Walport MJ, Davies KA: Accelerated nephrotoxic nephritis is exacerbated in C1q-deficient mice. J Immunol 166: 6820–6828, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.