Abstract

Using the behavioral model for vulnerable populations as a framework, this study examined predisposing, enabling, and need factors related to seeking help from formal and informal sources among older Black male foster youth and alumni. Results of logistic regression analyses showed that emotional control, a predisposing variable, was related to help-seeking. Specifically, greater adherence to the norm of emotional control was related to lower likelihood of using informal or formal sources of help. These results support the literature on males, in general, and Black males, in particular, that posits that inhibitions to express emotions are a barrier to their help seeking. Implications for help seeking among vulnerable populations of adolescent and young adult Black males are discussed.

Keywords: Black males, Help seeking, Informal help, Formal help, Emotional control

Introduction

The social and mental health indicators for foster care alumni coupled with those for Black males in the general population suggest that Black males transitioning from foster care may be a vulnerable sub-population. The general precarious status of adolescent and young adult Black males in the United States is indicated by a host of indicators which include disproportionality in unemployment and job loss, high school incompletion, out of wedlock births, incarceration, homicide, and suicide (Johnson 2010). In their study of foster care alumni, Dworsky et al. (2010) found racial differences that mirrored those among the general population of young adults. Black foster care alumni were more likely to be unemployed and teenage parents and less likely to be married. These and other mental health indicators suggest an increased need of mental health care to facilitate successful transitions from foster care.

The need for mental health services among older foster care youth and alumni cannot be under stated. Pecora et al. (2009a) found that across nine mental health disorders, foster care alumni had significantly higher lifetime prevalence as compared to similar-age individuals in the general population. For example, the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder was 41.1 % for foster care alumni compared to 21 % for the general population. Pecora et al. (2009b) also found that the rates of 12-month disorders among foster care alumni exceeded that of similar age individuals in the general population across eight mental health disorders. For example, rates of PTSD were 21.5 % for foster care alumni and 4.5 % for the general population.

Although significant ethnic group differences in mental health service use among foster care alumni are not evident in more recent studies (e.g., Harris et al. 2010), racial/ethnic disparities in receipt and use of mental health services, particularly outpatient mental health services, among children and youth in foster care are evident (e.g., Garland et al. 2003, 2005). In the longitudinal study from which the current study derived, McMillen et al. (2004) found that older foster care youth of color were only 40 and 31 % as likely to report lifetime and current outpatient therapy, respectively. With regard to the receipt of outpatient therapy in their lifetimes, the odds were higher among those with histories of physical and sexual abuse. In addition, the older youth were when they entered the foster care system, the lower their odds of lifetime outpatient therapy. With regard to current outpatient therapy, the odds increased among those with a 12-month psychiatric disorder (McMillen et al. 2004).

The Foster Care Independence Act (FCIA) of 1999 expanded the eligibility for care, support, and services to older youth in foster care up to age 21 (Collins 2004). Studying changes in mental health service use among young people leaving foster care, McMillen and Raghavan (2009) found that as age increased from 17 to 19 years, use of most mental health service types including outpatient specialized services significantly decreased. In addition, those who left custody by age 19 were significantly less likely to report use of mental health services than those who remained in custody.

The study of informal and formal help is perhaps the most common focus in the mental health services literature pertaining to the help seeking behaviors of Blacks. In a seminal study of use of informal and formal help, informal helpers consisted of family members (e.g., spouse, mother, and brother), other relatives, neighbors, friends, and coworkers (Neighbors and Jackson 1984). Formal sources of help included medical settings (e.g., emergency room, doctor’s office), mental health centers and professionals, and public/social service settings and professionals (e.g., police, school). Neighbors and Jackson (1984) found that Blacks relied more on informal help than professional help for their problems. In their analysis of data from the National Survey of Black Americans, Taylor et al. (1996) found that family members were the predominate source of informal assistance used for serious personal problems. In a more recent study among Blacks in the general population, Woodward et al. (2008) found that a greater proportion reported use of both professional and informal help. Consistent with previous research, there was greater reliance on informal support than professional services for help with mental health problems.

Concerning Black males, in particular, Lindsey et al. (2006), in their study of Black boys with high levels of depressive symptoms, found that informal networks of support, particularly family members and friends, were vital as sources of help for those both in treatment and not in treatment. Among a nationally-representative sample of Black men with mental disorders, Woodward et al. (2011) found the following: 33 % used both formal and informal sources of help, 14 % used professional sources of help only, 24 % used informal sources of help only, and 29 % sought no help. Those with a 12-month versus a lifetime mental disorder were more likely to use both formal and informal sources of help compared to using formal or informal sources of help only. Lower odds of using formal sources of help only were related to having some college or higher compared to having less than high school education and having a 12-month disorder compared to having a lifetime disorder only. Lower odds of using informal sources of help only were related to greater age, not having a job, having a 12-month disorder, and having a larger network of helpers. Finally, those who did not seek help had lower incomes, were working, had never married, and had a mental disorder or substance use disorder only.

The likelihood of Black males seeking help for mental health problems is influenced by a number of psychosocial and socio-cultural factors (Holden et al. 2012). Psychosocial factors include perceived racially discriminatory experiences and the stigma of mental illness. Black males who experience discriminatory experiences more frequently are likely to rely more on informal sources of help for mental health problems. It is noted by Holden et al. (2012) that racial discrimination compounds stigma beliefs and concerns. The experience of racial prejudice and discrimination along with beliefs that they will not only be mislabeled and mistreated by mental health service delivery systems and professionals, but viewed negatively by others because of their mental health problems is likely to preclude the seeking of help among Black males particularly from formal sources.

Sociocultural factors influencing the help seeking of Black males include mistrust of mental health service delivery systems and professionals (Holden et al. 2012). The impact of mistrust on medical care help seeking among Black males has been more established, empirically (e.g., Hammond et al. 2010). With regard to mistrust and mental health care help seeking, cultural mistrust, connoting the belief that “Whites cannot be trusted” (Terrell et al. 2009, p. 299) has been one of the most examined associated factors of the help seeking attitudes and treatment expectations among Blacks. For example, studying Black male undergraduate and graduate students, Duncan (2003) found that greater cultural mistrust was associated with less favorable attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help.

A factor that is considered very fundamental in the help seeking behaviors of males, in general, is masculine norms (Holden et al. 2012). Indeed, the link of masculine norms to male help seeking has received considerable attention (e.g., Addis and Mahalik 2003; Mahalik et al. 2003). However, the preponderance of the studies has focused more on help seeking attitudes than behaviors, and the study samples have consisted largely of White males. Nonetheless, these studies have consistently shown that males who adhere more to masculine norms such as emotional control hold more negative attitudes toward mental health services (e.g. Levant et al. 2009). In their study of the relevance of a mediation model of help seeking across cultures, Vogel et al. (2011) found that the relationship between masculine norms and help seeking attitudes was stronger for Black American males than for European-American, Asian American, and Latino American males.

Several seminal models have guided the preponderance of research on the receipt and seeking of health and mental health care. However, the model that has been most broadly applied and widely researched is Andersen’s (1995) behavioral model of health services. From the standpoint of this model, use of health services is argued to be a function of predisposing, enabling, and need factors (Gelberg et al. 2000). Using a modification of this model for the study of help seeking patterns among African American women, Caldwell (1996) identified predisposing factors as social and psychological characteristics existing before help seeking behavior, enabling factors as impediments to or facilitators of service use, and need characteristics as perceived or evaluated severity of problems.

Realizing that the conventional model failed to account for factors more intrinsic to the life and experiences of “vulnerable” populations, Gelberg et al. (2000) revised the model and delineated vulnerability factors for each successive phase leading up to health outcomes. For example, vulnerability factors such as group home placement, abuse and neglect history (i.e., predisposing factors), information sources (i.e., enabling factors), and health conditions (i.e., need factors) are viewed as supplements rather than replacements to traditional factors in the model.

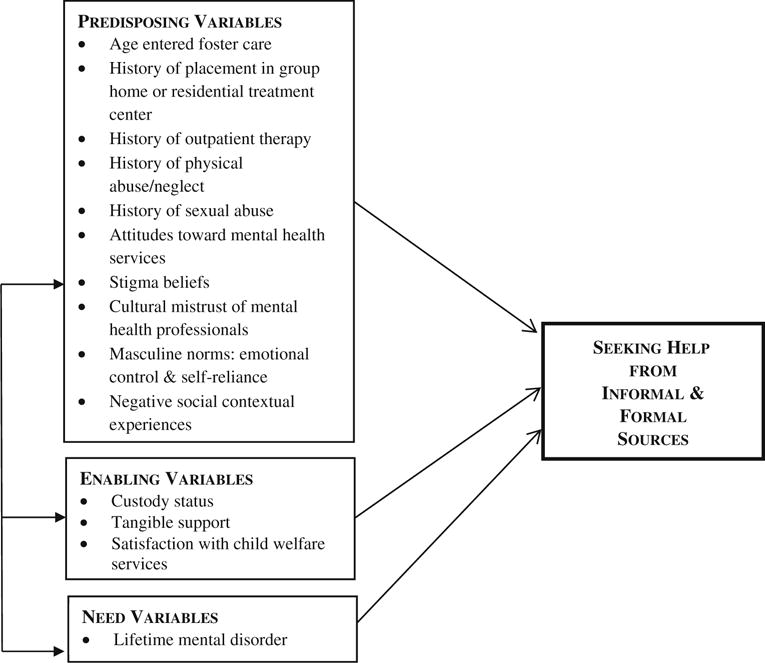

Using the behavioral model for vulnerable populations (Gelberg et al. 2000) as a framework, we posed the following research question: What predisposing, enabling, and need factors predict the seeking of help from informal and formal sources for personal, emotional, behavioral, or mental health problems among older Black male foster youth and alumni. A number of traditional variables (e.g., insurance coverage, employment status) are not evident in this study. However, psychosocial (e.g., stigma beliefs, negative social contextual experiences), socio-cultural (e.g., cultural mistrust of mental health professionals), and gender-related (e.g., masculine norms) variables not evident in previous studies are explored. Figure 1 depicts the application of the behavioral model for vulnerable populations in this study.

Fig. 1.

Application of behavioral model for vulnerable populations

Method

Data Sources and Sample

Data for the current study came from the following studies: (a) Male African American Help Seeking Study (MAAHS) and (b) Mental Health Service Use of Youth Leaving Foster Care (VOYAGES). VOYAGES is a longitudinal study of older youth transitioning from foster care (McMillen et al. 2004). Youth in VOYAGES were recruited from eight Missouri counties, which included six counties in and around St. Louis and two counties in Southwest Missouri that were added to make the sample more ethnically representative of youth in the state’s foster care system. The study sample of VOYAGES consisted of 406 older foster care youths (Mean Age = 16.99, SD = .09), 97 (23.9 %) of whom were Black males. Other details about the background and methods of the VOYAGES longitudinal study are described elsewhere (McMillen et al. 2004).

Of the 97 Black males in the VOYAGES longitudinal study, 74 (76.3 %) were successfully contacted and participated in the baseline interview of MAAHS. At baseline 69.1 % (n = 38) were still in the care and custody of the Missouri Children’s Division (MCD). Approximately 74 % (n = 55) of Black males who completed the MAAHS baseline interview participated in the follow-up interview. The mean number of days between the MAAHS baseline and follow-up interviews was 137 days (range 82–398 days, median = 109 days). Participants at followup were 18 (67.3 %), 19 (29.1 %), and 20 (3.6 %) years old. The rates for lifetime mental disorders were the following for participants in this study: oppositional defiant disorder (N = 15, 27.3 %); conduct disorder (N = 9, 16.4 %), major depression (N = 9, 16.4 %); attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (N = 9, 16.4 %), post-traumatic stress disorder (N = 2, 3.6 %), and mania (N = 2, 3.6 %).

Significant differences were found between MAAHS follow-up participants and non-participants. Follow-up participants were more likely to be in MCD custody at baseline and less likely to have a history of outpatient treatment than non-participants. There were no significant differences between follow-up and non-participants in terms of lifetime mental disorders, placement in group homes or residential treatment centers, physical abuse/neglect history, and age in which they entered foster care. This study is based on the 55 older Black male foster youth and alumni who completed both the MAAHS baseline and follow-up interviews.

Measures

A subset of the data used in this study was collected in the VOYAGES longitudinal study. All other predisposing and enabling variables were collected at baseline in the MAAHS study. Description of the predisposing, enabling, and need variables and the study from which they derived is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Predisposing, enabling, and need measures

| Measure/reference | Measure description | Description (No. of dimensions, No. of items, type, and scoring) | Reliability (current study) | Measure derived from |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry into foster care | Youths reported the age at which they first came into the foster care system | One self-report item: “How old were you when you entered DFS custody the first time?” | Not applicable | VOYAGES (baseline) |

| History of placement in group home or residential treatment center | Assessed by modified items from the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA; Stiffman et al. 2000) | Two self-report items: (a) “Have you ever stayed overnight in a Residential Treatment Center?”, and (b) “Have you ever stayed overnight in a group home?” | Not applicable | VOYAGES (baseline) |

| Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA; Stiffman et al. 2000) | A self-report tool that assesses any help or services for behavioral or emotional problems that a child or adolescent receives currently or received in the past | Services assessed included in current study: outpatient help from mental health professional Two self-report items: (a) “Have you ever received outpatient help (not overnight) from any professional like a psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker, or family counselor?”, and (b) “Are you currently using this service?” |

Not applicable | VOYAGES (baseline) |

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein and Fink 1998) | A self-report instrument that assesses types of maltreatment | Two dimensions of maltreatment (5 items each): physical abuse (e.g., “I was punished with a belt, a board, a cord, or some other hard object”); physical neglect (e.g., “I didn’t have enough to eat”) 5-point, Likert scale ranging from never true (1) to very often true (5) Cut-off score of 10 or above utilized to identify cases of moderate or severe abuse and neglect Youth were dichotomized into two physical neglect and physical abuse history groups: history of physical abuse/neglect (1) versus no physical abuse/neglect history (0) |

Internal reliability: α = .80 (physical abuse), .60 (physical neglect) | VOYAGES (baseline) |

| Sexual abuse history (Russell 1986) | Adapted to assess sexual abuse history | 3-item self-report tool: (a) if they were ever made to touch someone’s private parts against their wishes; (b) if anyone had ever touched their private parts (breasts or genitals) against their wishes; (c) if anyone ever had vaginal, oral, or anal sex with them against their wishes Dichotomized into two sexual abuse history groups: History of sexual abuse (Yes response to any of the three items; No history of sexual abuse (No response to all three items) |

Not applicable | VOYAGES (baseline) |

| Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPHS; Fischer and Turner 1970) | A 29-item self-report instrument for assessing attitudes toward traditional mental health services across four factors: recognition of need, stigma tolerance, interpersonal openness, and confidence in mental health practitioner | One dimension: Confidence in mental health practitioner subscale (8 items) modified by updating terms, dropping an out-of-date item, and adding one item on medications (“I think medications for emotional or behavioral problems can be helpful for many people”) 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4) Higher mean scores indicate more positive attitudes toward mental health services |

Internal reliability: α = .70 | VOYAGES (baseline) |

| Stigma (Link et al. 1989) | A self-report instrument for assessing beliefs about the devaluing and discrimination of people with serious mental health problems and beliefs about how people with serious mental health problems should cope | Two dimensions: Devaluation-discrimination (8 items; “Most people feel that getting help for serious mental health problems is a sign of weakness”); secrecy (3 items; “If you have been treated for a serious mental health problem, the best thing to do is keep it a secret”) Subscales modified to update terms and contextualize mental health problems and services 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) Higher mean scores indicate greater stigma beliefs |

Internal reliability: α = .70 (devaluation-discrimination), .73 (secrecy) | MAAHS (baseline) |

| Cultural Mistrust Inventory (CMI; Terrell and Terrell 1981) | A 48-item scale that measures the tendency of Blacks to mistrust Whites in four areas of life: educational and training settings, the political and legal system, work and business interactions, and interpersonal and social contexts | One dimension: Interpersonal Relations subscale (13 items) modified to assess participant’s beliefs and opinions about the trustworthiness of White mental health professionals (e.g., “It is best for Blacks to be on their guard when dealing with White mental health professionals”) 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) Higher mean scores indicate greater cultural mistrust of mental health professionals |

Internal reliability: α = .78 | MAAHS (baseline) |

| Conformity to Masculinity Norms Inventory (CMNI; Mahalik et al. 2003) | A 94-item scale that assesses 11 masculine norms: winning, emotional control, risk taking, violence, power over women, dominance, playboy, self-reliance, primacy of work, disdain for homosexuality, and pursuit of status | Two dimensions: Emotional control (11 items; e.g., “It is best to keep your emotions hidden”); self-reliance (6 items; e.g., “It bothers me when I have to ask for help”) 4-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (3) Higher mean scores indicate greater adherence to emotional control and self-reliance |

Internal reliability: α = .86 (emotional control), .80 (self-reliance) | MAAHS (baseline) |

| Black Male Experiences Measure (BMEM; Cunningham and Spencer 1996) | A 33-item scale that assesses the experiences and perceptions of Black males in four domains: proximal negative experiences (PNE); distal negative experiences (DNE); negative inference experiences (NIE); and positive inference experiences (PIE) | Three dimensions: Proximal negative experiences (8 items; e.g., “How often do people you don’t know think you are doing something wrong like selling drugs, preparing to rob somebody, preparing to steal something, etc.?”); distal negative experiences (9 items; e.g., “How often are you harassed by police?”); negative inference experiences (5 items; e.g., “How often do White people tend to lock their car doors when you pass?”) 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from never (1) to always (5) Higher mean scores indicate more frequent negative social contextual experiences |

Internal reliability: α = .92 (proximal negative experiences), .68 (distal negative experiences), .73 (negative inference experiences), .91 (total scale) | MAAHS (baseline) |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen and Hoberman 1983) | A 48-item scale measuring perceived social support along 4 dimensions: Tangible, Belonging, Self-Esteem, and Appraisal | One dimension: Tangible support subscale (12 items; e.g., “Lately, I often feel lonely, like I do not have anyone to reach out to”) Response options: True (1), False (0), Items summed to arrive at overall score: 0–12. Higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived tangible support |

Internal reliability: α = 73. | MAAHS (baseline) |

| Social Service Satisfaction Scale (R-GSSS: Reid and Gundlach 1983) | A 35-item scale that measures three dimensions of consumers’ general satisfaction with social services: relevance, impact, and gratification | Three dimensions: Relevance (11 items; e.g., “Overall, MCD is/was very helpful to me”); impact (11 items; e.g., “The MCD worker loves/loved to talk but will not/would not really do anything for me”); gratification (13 items; e.g., “I always feel/felt that I am/was treated well by MCD”) Modified to assess satisfaction with services from Missouri Children’s Division (MCD) 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) Higher mean scores indicate greater satisfaction with child welfare services |

Internal reliability: α = .82 (relevance), .76 (impact), .79 (gratification), and 92 (total scale), | MAAHS (baseline) |

| Diagnostic Interview Schedule-Version IV (DIS-IV; Robins et al. 1995) | A structured tool designed for use with a lay interviewer that assesses the recency, onset, and duration of DSM-IV diagnoses | Disorders assessed were posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression, mania, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional disorder, and conduct disorder | Not reported | VOYAGES (baseline) |

Informal and Formal Help seeking Outcome Measures

The seeking of help from informal and formal sources was assessed in the MAAHS follow-up interview. Three dichotomous items assessed informal sources of help. Participants were asked if they sought help from any of the following sources for any personal, emotional, behavioral, or mental health problems: minister or someone else at your church or place or worship, family member, and friend. For each item, the possible response was “yes” (coded as 1) or “no” (coded as 0). If participants reported using any of the three sources, the combined variable was coded as 1. The combined variable was coded as 0 if participants reported they did not use any of the three sources.

Seeking help from formal sources was assessed by one dichotomous item. Participants were asked the following question: “Since we last met, did you talk to a mental health professional (like counselor/therapist, social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist) OR go to mental health center/clinic for any personal, emotional, behavioral, or mental health problems voluntarily (meaning you did it because you wanted to)?” The possible response was “yes” (coded as 1) or “no” (coded as 0).

Procedures

Black males in the VOYAGES longitudinal study were contacted directly to solicit their participation in MAAHS. None of those contacted refused to participate. Upon providing informed consent, participants were interviewed during the period of July 2003 to November 2004 in person at their place of residence (89.1 %) or by telephone (10.9 %). Those interviewed face-to-face tended to (a) be older at age of entrance into foster care (b) report more frequent negative social contextual experiences, and (c) report higher levels of tangible support than those interviewed by phone. The assessment tools were read aloud to control for difference in reading abilities. Participants were paid $20 each for the baseline and follow-up interviews. The Washington University Institutional Review Board approved the procedures for this study.

Analysis

Data analysis occurred in the following steps. First, descriptive statistics were computed to provide a profile of the sample on the primary study variables. Second, Chi square tests and independent samples t tests were conducted to examine group differences between those who sought help from informal and formal sources and those who did not by categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. Only variables that had an association of p < .20 with informal and formal help seeking at the bivariate level were included in subsequent analyses.

To assess multicollinearity between independent variables associated with seeking help from informal and formal sources, separate hierarchical regression analyses with predisposing, enabling, and need variables entered in successive blocks were conducted. Results showed acceptable tolerance levels with the lowest being .59. Last, we used a hierarchical approach in logistic regression analyses to examine informal help seeking and formal help seeking. For dichotomous logistic regressions, a skew beyond an “80–20 split” on the dependent variable is recommended for better estimates (Morrow-Howell and Proctor 1992, p. 96). This criterion was also used for determining inclusion of categorical independent variables in logistic models. Predisposing variables were entered in Model 1; enabling variables were entered in Model 2; and need variables were entered in Model 3. All results were adjusted for the effects of mode of interview.

Results

Participants reported seeking help more from informal than formal sources. Only six (10.9 %) reported seeking help from formal sources. Seventeen (30.9 %) reported seeking help from informal sources. Of the informal sources of help measured, 1.8 % (n = 1) reported seeking help from a minister or someone else at church/place of worship, 27.3 % (n = 15) from a family member, and 16.4 % (n = 9) from a friend. Approximately 5.5 % (n = 3) sought help from both formal and informal sources, and 63.6 % (n = 35) reported not seeking help from either sources. Twenty (36.4 %) reported seeking help from either informal or formal sources of help.

Results of Chi square tests examining group differences between seekers and non-seekers of informal and formal sources of help on categorical variables are shown in Table 2. As shown, the only variable significantly related to seeking help from informal and formal sources was lifetime mental disorder. A higher proportion of older Black male foster youth and alumni who met criteria for a lifetime mental disorder sought help from both sources.

Table 2.

Chi square tests of voluntary use of informal and formal sources of help by categorical variables

| Variable | Use of informal sources of help N (%) | Use of formal sources of help N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Time b/w baseline and follow-up interviews | ||

| 1–4 months (n = 30) | 11 (36.7 %) | 2 (6.7 %) |

| 5 or months (n = 25) | 6 (24 %) | 4 (16 %) |

| Time b/w interview differences (χ2) | 1.02 | 1.22 |

| History of placement in group home or residential treatment center | ||

| No (n = 10) | 1 (10 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Yes (n = 45) | 16 (35.6 %) | 6 (13.3 %) |

| Placement history differences (χ2) | 2.50 | 1.50 |

| Current/past outpatient therapy | ||

| No (n = 37) | 9 (24.3 %) | 3 (8.1 %) |

| Yes (n = 18) | 8 (44.4 %) | 3 (16.7 %) |

| Outpatient therapy history differences (χ2) | 2.29 | .91 |

| Physical abuse/neglect history | ||

| No (n = 22) | 6 (27.3 %) | 3 (13.6 %) |

| Yes (n = 33) | 11 (33.3 %) | 3 (9.1 %) |

| Physical abuse/neglect differences (χ2) | .23 | .28 |

| Sexual abuse history | ||

| No (n = 47) | 15 (31.9 %) | 5 (10.6 %) |

| Yes (n = 8) | 2 (25 %) | 1 (12.5 %) |

| Sexual abuse differences (χ2) | .15 | .02 |

| Custody status at baseline | ||

| Not In MCD Custody (n = 17) | 5 (29.4 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| In MCD Custody (n = 38) | 12 (31.6 %) | 6 (15.8 %) |

| Custody differences (χ2) | .03 | 3.01+ |

| Lifetime mental disorder | ||

| No (n = 24) | 4 (16.7 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Yes (n = 31) | 13 (41.9 %) | 6 (19.4 %) |

| Mental disorder differences (χ2) | 4.04* | 5.21* |

p ≤ .20;

p ≤ .10;

p <.05;

p <.01

Results of independent samples t tests for informal and formal sources of help are reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. As shown in Table 3, emotional control and negative social contextual experiences were significantly related to seeking help from informal sources. Those who sought help from informal sources reported lower adherence to emotional control and more frequent negative social contextual experiences than nonusers. With regard to seeking help from formal sources (Table 4), satisfaction with child welfare services was significantly related. Those seeking help from formal sources reported greater satisfaction with child welfare services.

Table 3.

Group differences between users and nonusers of informal sources of help

| Continuous variable | Used informal sources of help (N = 17) M (SD) | Did not use informal sources of help (N = 38) M (SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age entered foster care | 7.94 (5.20) | 9.68 (4.68) | 1.23 |

| Attitudes toward mental health services | 2.33 (.80) | 2.42 (.68) | .42 |

| Stigma beliefs | |||

| Devaluation-discrimination | 2.70 (.79) | 2.63 (.69) | −.33 |

| Secrecy | 2.49 (.96) | 2.25 (1.02) | −.80 |

| Cultural mistrust of mental health professionals | 2.66 (.58) | 2.54 (.61) | −.73 |

| Adherence to masculine norms | |||

| Emotional control | 1.03 (.46) | 1.40 (.51) | 2.52* |

| Self-reliance | 1.00 (.44) | 1.17 (.62) | 1.04 |

| Negative social contextual experiences | 2.77 (.73) | 2.34 (.76) | −1.96* |

| Tangible support | 5.41 (1.80) | 5.62 (1.34) | .48 |

| Satisfaction with child welfare services | 3.21 (.83) | 3.34 (.73) | .59 |

p < .05

Table 4.

Group differences between users and nonusers of formal sources of help

| Continuous variable | Used formal sources of help (N = 6) M (SD) | Did not use formal sources of help (N = 49) M (SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age entered foster care | 9.00 (6.16) | 9.16 (4.76) | .08 |

| Attitudes toward mental health services | 2.57 (1.05) | 2.38 (.68) | −.58 |

| Stigma beliefs | |||

| Devaluation-discrimination | 2.44 (.74) | 2.67 (.52) | .74 |

| Secrecy | 2.50 (1.02) | 2.31 (1.01) | −.44 |

| Cultural mistrust of mental health professionals | 2.14 (.37) | 2.62 (.60) | 1.94+ |

| Adherence to masculine norms | |||

| Emotional control | 1.00 (.49) | 1.32 (.52) | 1.42 |

| Self-reliance | .85 (.59) | 1.15 (.57) | 1.19 |

| Negative social contextual experiences | 2.03 (.65) | 2.53 (.77) | 1.48 |

| Tangible support | 4.58 (.92) | 5.67 (1.49) | 1.74+ |

| Satisfaction with child welfare services | 3.96 (.36) | 3.22 (.75) | −4.00** |

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01

Results of logistic regression analyses appear in Table 5. Logistic regression analysis of formal help-seeking yielded inflated and uninterpretable parameter estimates that was likely due to the small study sample and low percentage of participants who reported having sought help from formal sources. Furthermore, results of logistic regression analyses for informal help seeking only and the seeking of help from either informal or formal sources were virtually the same. Hence, we report the results for seeking help from either informal or formal sources.

Table 5.

The association between predisposing, enabling, and need variables and use of informal and/or formal sources of help

| Variable | Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95 % CI | Odds ratio | 95 % CI | Odds ratio | 95 % CI | |

| Predisposing variables | ||||||

| Cultural mistrust of mental health professionals | .82 | 0.27–2.45 | .64 | 0.18–2.23 | .64 | 0.16–2.52 |

| Emotional control | .09** | 0.02–0.53 | .03** | 0.00–0.37 | .03** | 0.00–0.42 |

| Negative social contextual experiences | 2.46+ | 0.93–6.46 | 3.04* | 1.01–9.17 | 2.45 | 0.73–8.26 |

| Enabling variables | ||||||

| Custody Status at Baselinea | 1.23 | 0.20–7.41 | .99 | 0.16–6.13 | ||

| Tangible Support | .55+ | 0.30–1.06 | .51+ | 0.27–0.97 | ||

| Satisfaction with Child Welfare Services | .99 | 0.33–2.96 | 1.04 | 0.33–3.26 | ||

| Need variables | ||||||

| Lifetime mental disordera | 4.41+ | 0.93–21.00 | ||||

| Model fit | ||||||

| −2LL | 56.17 | 50.78 | 46.91 | |||

| Nagelkerke’s R2 | .31 | .41 | .48 | |||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 11.22, p = .19 | 3.95, p = .86 | 5.81, p = .67 | |||

Comparison category is Yes

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01

In Model 1, the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic was not significant (χ2 = 11.22, p = .19, −2LL = 56.17), indicating a well-fitting model. In results for that model, emotional control was a significant predictor. As adherence to emotional control increased, the likelihood of seeking help from either informal or formal sources decreased.

In Model 2, the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic was not significant (χ2 = 3.95 p = .86, −2LL = 50.78), indicating a well-fitting model. In results for that model, none of the added enabling variables were significant predictors. Emotional control continued to be a significant predictor and negative social contextual experiences evolved as a significant predictor in Model 2. The likelihood of seeking help from either informal or formal sources increased as the frequency of negative social contextual experiences increased in this model.

In the final logistic regression model (Model 3), the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic was not significant (χ2 = 5.81, p = .67, −2LL = 46.91), indicating a well-fitting model. Emotional control continued to be a significant predictor in Model 3. Negative social contextual experiences decreased to non-significance when lifetime mental disorder was entered in the final model. However, having a lifetime mental disorder did not significantly lower or increase the likelihood of seeking help from either informal or formal sources.

Discussion

Using Andersen’s behavioral model for vulnerable populations as a theoretical framework, this study examined predisposing, enabling, and need variables and their relationship to help seeking from informal and formal sources of help among older Black male foster youth and alumni. Consistent with previous research on the help seeking behaviors of Blacks, we found greater help seeking from informal sources than formal sources.

Lindsey (2010) notes that the sources of help sought out first by young Black males are likely to be friends and family members in that they are considered more trustworthy and relatable. Furthermore, friends and family members may help Black males and facilitate their well-being in different, but complimentary ways. As noted by Taylor et al. (1996), the bolstering of identity and self-worth is one of several functions of friends and peers. Due to shared characteristics, individuals may easily gravitate toward friends particularly for problems that fluctuate. Lindsey et al. (2010) note that adolescent and young adult Black males are not likely to ‘let on to one another’ that they are distressed or depressed. At best, such issues are likely to be discussed informally or indirectly (Lee and Bailey 2006). Hence, help for emotional or psychological issues are not likely to be sought from friends. But in more concrete and visible areas of life, shared experiences have a coalescing effect, signifying their status as “Brothers” (White and Cones 1999, p. 214).

For problems that are long-standing, individuals are more likely to turn to family members than friends (Taylor et al. 1996). The problems faced by Black males transitioning from foster care are arguably more long-standing than fluctuating. Interestingly, despite foster care histories where many family ties were likely tenuous due to issues of abuse and neglect and were disrupted or disjointed by multiple placements, participants in our study relied foremost on family members for help with their personal, behavioral, and mental health problems. This consistent finding across studies among varied samples of Blacks bespeaks the intrinsic nature and value of social supports in Black family and community life (Jewell 1988).

In bivariate analyses, a number of factors evolved as correlates of informal or formal sources of help that are consistent with the literature. For example, older Black male foster youth and alumni who met DSM-IV criteria for a lifetime mental disorder were more likely to seek help from informal and formal sources. Having a mental disorder is a primary indicator of need (Proctor and Stiffman 1998). As such, our findings suggest that those in greatest need of mental health care more often sought help.

With regard to informal sources of help, participants reporting higher levels of negative social contextual experiences were more likely to report seeking help from informal sources. Negative experiences based on gender and race is part of a constellation of stressors that can affect physiological and emotional well-being (Harrell 2000). For adolescent and young adult Black males, the insidious nature of these experiences can erode a positive sense of self and activate negative emotions and anger that contribute to destructive behaviors (Stevenson 2004). That young Black males would seek help primarily from informal sources the more frequent these experiences occur is commonsensical in that outsiders are likely to be considered more untrustworthy and unsympathetic.

In bivariate results for formal sources of help, older Black male foster youth and alumni who reported greater levels of satisfaction with child welfare services were more likely to report seeking help from formal sources. Franklin (1992) asserted that experiences of Black males with public agencies and institutions such as child or social welfare agencies and juvenile courts are consequential to how they view mental health care. To the extent that their experiences have been unsatisfactory and problematic, they are likely to avoid seeking out professional help in times of need. The converse is likely to be true for those whose experiences and receipt of services within public agencies and institutions has been more satisfactory. A caveat concerning this finding in our study is that all those who reported seeking help from formal sources were still in the care and custody of state authorities. Whether their greater use of formal sources of help is a true indication of their satisfaction with child welfare services or a function of greater access and/or compulsion is hard to determine.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to take a prospective approach in examining the relation of specific masculine norms to seeking help from informal or formal sources. Our findings were consistent with the literature on males, in general, and Black males, in particular, that posits that inhibitions to express emotions is a barrier to their help seeking as well as engagement in counseling (e.g., Addis and Mahalik 2003; Holden et al. 2012; Lee and Bailey 2006).

Lindsey et al. (2010) note how the expression of emotions puts young Black males in a serious quandary. On one hand, the expression of feelings such as pain provides an opportunity for someone to notice that help is needed. On the other hand, to express such feelings puts them at risk for ridicule because their vulnerability is noticed or exposed. Being considered “like a girl” or “soft” must be avoided at all cost (Lindsey et al. 2006, p. 54). Any semblance of vulnerability could exacerbate situations where further infliction of emotional or physical pain is possible or imminent. Anderson’s (1990) reference to the predicament of Black males as a “cultural catch-22” (p. 177) is appropriate as it relates to this issue. Though restrictiveness in expressions of emotions is not a Black male phenomenon only, Anderson asserts that the contexts in which many adolescent and young adult Black males navigate heighten their avoidance of signs of weakness and vulnerability.

How to address cultivated and cultural norms that inhibit help seeking is not easily answerable. Countering messages and norms that stifle expressions of hurt and pain is particularly important in venues and outlets where adolescent and young adult Black males are more likely to congregate and interact (e.g., churches, barber shops, recreational centers). In this regard, the use of hip-hop culture in certain venues should not be overlooked. Though many elements of hip-hop culture are concerning to many, its power to influence perceptions, opinions and behaviors should not be underestimated. For example, in a past issue of XXL, a hip-hop magazine, the rapper Joe Budden stated that therapy saved his life (Linden 2006). The story of Joe Budden’s life reads like many Black males who have interfaced with the child welfare and mental health care systems. Having suffered from clinical depression, the rapper explicitly indicates that his life would be far worse off if it were not for the therapy he received throughout his life. Stories of adolescent and young adult Black males who have sought or received mental health services and have benefitted from them will go a long way in the reframing of help seeking as a “positive proactive behavior” (Lindsey et al. 2006, p. 56).

Young Black men also need to know that there are therapies that are not emotion focused, that will not ask them to emote in ways perceived as weak or injurious to their self-worth in order to get better. For example, cognitive therapies focus on more helpful thinking and the diffusion of unhelpful thinking. These may have more appeal to them than the therapies they envision. Though existing research does suggest a greater preference among Black men for therapeutic approaches that are more direct and less introspective, Rasheed and Rasheed (1999) suggest that prevailing notions that Black men lack the “ego strength” to be introspective and engage with intensive treatment may more so reflect biases of formal mental health service systems and professionals (p. 50). Furthermore, that both the solicitation of assistance and the provision of outpatient mental health care by formal providers often occur in milieus that exacerbate mistrust should not be dismissed as a contributing factor (Franklin 2004). On the part of formal systems and professionals, a proactive self- and organizational assessment of (a) how Black men view their services, (b) how Black men are related to personally and professionally, and (c) how programs and policies may be complicit in fostering an environment similar to other oppressive contexts where Black men navigate are critically important for any meaningful therapeutic engagement (Franklin 2004).

A major strength of the current study was its prospective approach to the examination of informal and formal help seeking. Furthermore, we accounted for a number of important psychosocial and socio-cultural factors. Though factors such as mistrust, stigma, and masculine norms are linked to the help seeking behaviors of Black males, this is one of the few studies evident in the literature that assesses them prospectively. In light of these strengths, a number of limitations are notable. The cross-sectional research design restricts the ability to draw causal conclusions. Furthermore, the small, non-representative sample of older Black male foster youth and alumni limits the generalizability of the findings. The small sample size also likely reduced statistical power, thereby obscuring significant bivariate and multivariate relationships. A final limitation important to mention concerns some of the measures used in this study. A number of them were modified for purposes of this study. Although estimates of the reliability for most of the modified measures were adequate, the construct validity of the instruments might have been compromised. Hence, findings should be interpreted with caution.

There are several important directions that future research might pursue. It is important that research assess a wide range of informal and formal helpers to further elucidate help-seeking preferences. Though the direction of many non-significant findings in our study was supportive of the literature, studies among larger clinical/community samples as well as nationally-represented samples of vulnerable populations of adolescent and young adult Black males are critical for adequate statistical power and better elucidation of the influence of psychosocial and sociocultural factors. In addition, the inclusion of more traditional variables such as insurance coverage and employment status will provide a more complete picture of their help seeking patterns.

Since the implementation of this study, a number of measures have appeared in the literature that specifically assesses the variables of interest, hence requiring no modification that would alter their psychometric properties. For example, Vogel et al. (2006) introduced the Self-Stigma of Seeking Help Scale, which is a uni-dimensional measure that assesses whether seeking help from a mental health professional reduces individual’s sense of self-regard, esteem, and -confidence. In addition, Mansfield et al. (2005) has introduced the Barriers to Help-Seeking Scale (BHSS), which was specifically developed to assess obstacles to men seeking help for mental health problems. Despite the promise of these measures, they were normed primarily on White college student samples. It is important that their cross-ethnic/racial equivalency be established. It is also pertinent that measures of psychosocial and sociocultural factors normed on Black males be developed and validated.

In conclusion, elucidating and understanding those factors that act as barriers as well as facilitators to older Black male foster youth and alumni seeking help for personal, behavioral, and mental health problems is imperative for systems of care, mental health professionals, and familial and community supports. Receiving the mental health care needed to help with a myriad of challenges and to move them toward more successful transitions from foster care is critically important for their short- and long-term well-being.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH61404 and 5R03MH067124-02).

Contributor Information

Lionel D. Scott, Jr., Email: lscottjr@gsu.edu, School of Social Work, Georgia State University, P.O. Box 3995, Atlanta, GA 30302, USA.

J. Curtis McMillen, The School of Social Service Administration, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Lonnie R. Snowden, School of Public Health, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

References

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist. 2003;58:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Streetwise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH. Predisposing, enabling, and need factors related to patterns of help seeking among African American women. In: Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, editors. Mental health in Black America. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. pp. 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1983;13:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Collins ME. Enhancing services to youths leaving foster care: Analysis of recent legislation and its potential impact. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:1051–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Spencer MB. The black male experiences measure. In: Jones RL, editor. Handbook of tests and measurements for Black populations. Hampton: Cobb & Henry Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LE. Black male college students’ attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Black Psychology. 2003;29:68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dworsky A, White C, O’Brien K, Pecora P, Courtney M, Kessler R, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in the outcomes of former foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:902–912. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EH, Turner JI. Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1970;35:79–90. doi: 10.1037/h0029636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ. Therapy with African American men. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 1992;73:350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ. From brotherhood to manhood: How Black men rescue their relationships and dreams from the invisibility syndrome. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Landsverk JA, Lau AS. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among children in foster care. Children & Youth Services Review. 2003;25:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research. 2000;34:1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond W, Matthews D, Mohottige D, Agyemang A, Corbie-Smith G. Masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays among community-dwelling African-American men. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Jackson LJ, O’Brien K, Pecora P. Ethnic group comparisons in mental health outcomes of adult alumni of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Holden KB, McGregor BS, Blanks SH, Mahaffey C. Psychosocial, socio-cultural, and environmental influences on mental health help seeking among African-American men. Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;9:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell KS. Survival of the African American family: The institutional impact of US social policy. New York: Praeger; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WE, editor. Social work with African American males: Health, mental health, and social policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Bailey DF. Counseling African American male youth and men. In: Lee CC, editor. Multicultural issues in counseling: New approaches to diversity. 3rd. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association; 2006. pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Wimer DJ, Williams CM, Smalley K, Noronha D. The relationships between masculinity variables, health risk behaviors and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2009;8(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Linden A. All good. XXL. 2006;10(1):104–106. 108, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA. What are depressed African American adolescent males saying about mental health services and providers? In: Johnson WE Jr, Johnson WE Jr, editors. Social work with African American males: Health, mental health, and social policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Joe S, Nebbitt V. Family matters: The role of mental health stigma and social support on depressive symptoms and subsequent help seeking among African American boys. Journal of Black Psychology. 2010;36(4):458–482. doi: 10.1177/0095798409355796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Korr WS, Broitman M, Bone L, Green A, Leaf PJ. Help seeking behaviors and depression among African American adolescent boys. Social Work. 2006;51:49–58. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Good GE, Englar-Carlson M. Masculinity scripts, presenting concerns, and help seeking: Implications for practice and training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003a;34:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RPJ, Gottfried M, et al. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2003b;4:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield AK, Addis ME, Courtenay W. Measurement of men’s help seeking: Development and Evaluation of the Barriers to Help Seeking Scale. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, Raghavan R. Pediatric to adult mental health service use of young people leaving the foster care system. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, Scott LD, Zima BT, Ollie MT, Munson MR, Spitznagel E. Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatric Services. 2004;52:189–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N, Proctor EK. The use of logistic regression in social work research. Journal of Social Service Research. 1992;16:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. The use of informal and formal help: Four patterns of illness behavior in the Black community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1984;12:629–644. doi: 10.1007/BF00922616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, Jensen PS, Romanelli LH, Jackson LJ, Ortiz A. Mental health services for children placed in foster care: An overview of current challenges. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program. 2009a;88:5–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, White CR, Jackson LJ, Wiggins T. Mental health of current and former recipients of foster care: A review of recent studies in the USA. Child & Family Social Work. 2009b;14:132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Stiffman AR. Background of services and treatment research. In: Williams JBW, Ell K, editors. Advances in mental health research: Implications for Practice. Washington, D.C: NASW Press; 1998. pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed JM, Rasheed MN. Social work practice with African American men: The invisible presence. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reid PN, Gundlach JH. A scale for the measurement of consumer satisfaction with social services. Journal of Social Service Research. 1983;7:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St. Louis, MO: Washington University in St. Louis; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DEH. The secret trauma: Incest in the lives of girls and women. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC. Boys in men’s clothing: Racial socialization and neighborhood safety as buffers to hypervulnerability in African American adolescent males. In: Way N, Chu JY, editors. Adolescent boys: Exploring diverse cultures of boyhood. New York: New York University Press; 2004. pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K. The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): Adult and child reports. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1032–1039. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R, Hardison C, Chatters LM. Kin and nonkin as sources of informal assistance. In: Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, editors. Mental health in Black America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. pp. 130–145. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Taylor J, Menzise J, Barrett RK. Cultural mistrust: A core component of African American consciousness. In: Neville HA, Tynes BM, Utsey SO, editors. Handbook of African American psychology. Los Angeles: Sage; 2009. pp. 209–309. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Terrell S. An inventory to measure cultural mistrust among Blacks. The Western Journal of Black Studies. 1981;5:180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Heimerdinger-Edwards SR, Hammer JH, Hubbard A. “Boys don’t cry”: Examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:368–382. doi: 10.1037/a0023688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- White JL, Cones JH. Black man emerging: Facing the past and seizing a future in America. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AT, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Neighbors HW, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Use of professional and informal support by African Americans and Caribbean Blacks with mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:1292–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward A, Taylor R, Chatters LM. Use of professional and informal support by Black men with mental disorders. Research On Social Work Practice. 2011;21:328–336. doi: 10.1177/1049731510388668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]