Abstract

ISEcp1B is an insertion element associated with the emerging expanded-spectrum β-lactamase blaCTX-M genes in Enterobacteriaceae. Because ISEcp1B-blaCTX-M positive strains may be identified from humans and animals, the ability of this insertion sequence to mobilize the blaCTX-M-2 gene was tested from its progenitor Kluyvera ascorbata to study the effects of amoxicillin/clavulanic and cefquinome as enhancers of transposition. These β-lactam molecules are administered parenterally to treat infected animals. ISEcp1B-mediated mobilization of the blaCTX-M-2 gene from K. ascorbata to a plasmid location in Escherichia coli J53 was studied. Transposition assays were performed with overnight cultures with amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid and cefquinome at concentrations expected to mimic those found in feces after parenteral administration (0.4–0.008 mg L−1 and 0.32–0.064 mg L−1, respectively). Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and cefquinome did not modify the transposition frequency (1.85 ±1.7 ×10−7) whereas ceftazidime (0.5 mg L−1), used as a control, did (5.2 ±2.7 ×10−5). Therefore, it is likely that neither amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid nor cefquinome concentrations as found in the gut flora may enhance mobilization of the blaCTX-M genes in Enterobacteriaceae.

Introduction

Worldwide reports of expanded-spectrum β-lactamases of the CTX-M type in Enterobacteriaceae are increasing and mostly in Escherichia coli (Pitout et al., 2005; Canton & Coque, 2006; Livermore et al., 2007). These enzymes are now widespread not only in human but also in animal isolates (Shiraki et al., 2004; Kojima et al., 2005; Girlich et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007; Schroer et al., 2007). The 40 CTX-M-type β-lactamases may be grouped into five main subgroups according to amino acid sequence identity (CTX-M-1, -M-2, -M-8, -M-9 and -M-25) (Canton & Coque, 2006). Several genetic elements are associated with blaCTX-M genes, the most important being insertion sequence ISEcp1 (Lartigue et al., 2004). ISEcp1 mobilizes the downstream-located gene by a one-ended transposition mechanism and provides strong promoter sequences for high-level blaCTX-M expression (Poirel et al., 2003, 2005). We have been able to show that subinhibitory concentrations of several β-lactam molecules may induce ISEcp1B-mediated transposition (Lartigue et al., 2006). The chromosome-encoded β-lactamases of several Kluyvera species have been identified as progenitors of CTX-M-type enzymes such as CTX-M-2 subgroups deriving from Kluyvera ascorbata (Humeniuk et al., 2002; Poirel et al., 2002).

Many β-lactam molecules are used for the treatment of infected animals, including amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefazolin, cefoperazone, ceftiofur (third-generation cephalosporin) and cefquinome (fourth-generation cephalosporin). Ceftiofur and cefquinome have restricted usage for veterinary medicine; cefquinome is indicated as an individual injectable or intramammary treatment to pigs, cattle and horses (Hornisch & Kotarski, 2002). The aim of this study was to test the ability of two prescribed antibiotic molecules in veterinary medicine, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and cefquinome to induce ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-2 transposition.

Material and methods

We have used an in vivo model of transposition based previously on mobilization of a blaCTX-M-2 gene from a chromosomal location reservoir K. ascorbata to a plasmid location in E. coli (Lartigue et al., 2006). The studied concentrations of those antibiotics corresponded to antibiotic concentrations expected in feces of treated animals (where blaCTX-M-positive enterobacterial isolates have mostly been identified). (The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 1995).

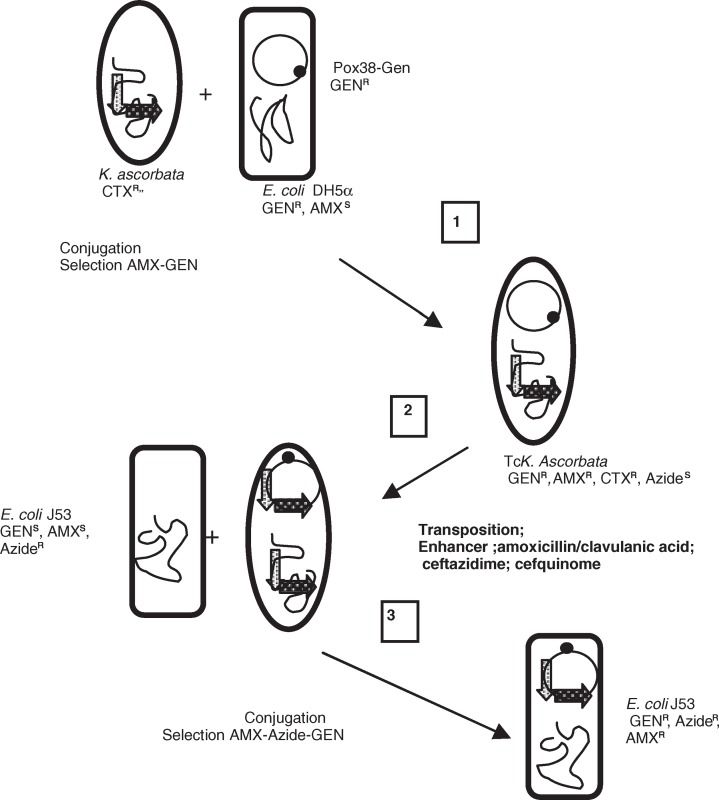

The recombinant K. ascorbata CIP7953 reference strain, in which ISEcp1B was inserted upstream of the blaCTX-M-2 gene, was used as a donor strain. The transposition ability of ISEcp1B-blaKLUA was investigated by conjugation with E. coli-containing plasmid pOX38-GEN (Fig. 1). Plasmid pOX38-GEN was used as a target for transposition events. Transfer of pOX38-GEN from E. coli into the K. ascorbata transformants was performed, and transconjugants were selected on agar plates containing 7 mg L−1 of GEN (plasmid marker) and 100 mg L−1 of AMX (chromosomal marker). Transposition events were searched between the chromosomal blaCTX-M-2 gene and the recipient plasmid pOX38-GEN after overnight growth in trypticase soy broth with and without antibiotics at different subinhibitory concentrations. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was tested at 2, 0.4, 0.04 and 0.008 mg L−1 (fixed concentration of clavulanic acid at 4 mgl L−1) and cefquinome at 3.2, 0.32 and 0.064 mg L−1, respectively, whereas ceftazidime, used as a positive control (Lartigue et al., 2006), was tested at 0.5 mg L−1. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefquinome and ceftazidime were 512 mg L−1, 1 mg L−1 and 0.5 mg L−1, respectively, for the K. ascorbata strain CIP7953 harboring ISEcp1B-blaKLUA.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of ISEcp1B-mediated mobilization of the naturally occurring CTX-M-2 β-lactamase gene of Kluyvera ascorbata CIP7953.

(1) Transfer of recipient plasmid in cefotaxime-resistant K. ascorbata strains that has an ISEcp1B inserted upstream of the blaCTX-M-2 gene.

(2) ISEcp1B mobilizes the blaCTX-M-2 gene from its chromosomal location in K. ascorbata on plasmid under various conditions: +/− amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, +/− cefquinome, +/−ceftazidime.

(3) Plasmid-located events of transposition are isolated.

ISEcp1B

ISEcp1B

blaCTX-M

blaCTX-M

AMX, amoxicillin; CTX, cefotaxime; GEN, gentamicin.

Then, transfer of the recombinant plasmids with the pOX38-GEN backbone into the E. coli J53AZr strain was performed by conjugation, and transconjugants were selected on agar plates containing 7 mg L−1 of GEN (plasmid marker), 100 mg L−1 of AMX (transposon marker) and 100 mg L−1 of azide (chromosomal marker). The transposition frequency was calculated by dividing the number of transconjugants by the number of donor bacteria.

Results

Transposition of the ISEcp1B-blaCTX-M-2 DNA fragment occurred at a frequency of 6.4 ±0.5 ×10−7 in E. coli. No significant difference in the transposition frequency was found with or without amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or cefquinome addition at the tested concentrations. In contrast, the transposition frequency of ISEcp1B-blaKLUA was 100-fold higher when ceftazidime was added at 0.5 μg mL−1 (5 ± 2.5 ×10−5).

Conclusion

Our results indicated that, under the experimental conditions used, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and cefquinome, at concentrations found in feces of treated animals, may not enhance ISEcp1B-mediated transposition of the blaCTX-M genes in the fecal flora. Our model is based on the blaCTX-M-2 gene, which is a β-lactamase gene identified in E. coli from cattle, pigs and Salmonella spp. from chicken. These results shall be included in the current debate on the role of antibiotics in promoting the spread and/or the selection of the blaCTX-M gene in animals (Feldgarden, 2007).

Future work may also be directed toward identifing the environmental reservoir of Kluyvera spp. in an attempt to control its spread.

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by a grant from the Ministère de l’Education Nationale et de la Recherche (UPRES-EA3539), Université Paris XI, Paris, France, and mostly by the European Community (6th PCRD, LSHM-CT-2003-503-335).

References

- Canton R, Coque TM. The CTX-M β-lactamase pandemic. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;69:466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldgarden M. Cefquinome; when regulation collides with biology. ASM Microbes. 2007;2:272–273. [Google Scholar]

- Girlich D, Poirel L, Carattoli A, Kempf I, Lartigue MF, Bertini A, Nordmann P. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-1 in Escherichia coli isolates from healthy poultry in France. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4681–4685. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02491-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornisch RE, Kotarski SF. Cephalosporins in veterinary medicine. Ceftiofur use in food animals. Curr Topics Med Chem. 2002;2:717–731. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk C, Arlet G, Gautier V, Grimont P, Labia R, Philippon A. β-Lactamases of Kluyvera ascorbata, probable progenitors of some plasmid-encoded CTX-M types. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3045–3049. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3045-3049.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima A, Ishii Y, Ishihara K, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from farm animals from 1999 to 2002; report from the Japanese Veterinary Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3533–3537. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3533-3537.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartigue MF, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Diversity of genetic environment of the blaCTX-M genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;234:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartigue MF, Poirel L, Aubert D, Nordmann P. In vitro analysis of ISEcp1-mediated mobilization of naturally-occurring β-lactamase gene bla CTX-M of Kluyvera ascorbata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1282–1286. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1282-1286.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XZ, Mehrotra M, Ghimire S, Adewoye L. β-Lactam resistance and β-lactamases in bacteria of animal origin. Vet Microbiol. 2007;15:197–214. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore DM, Canton R, Gniadkowski M, et al. CTX-M: changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:165–174. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Laupland KB, Poirel L. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:52–59. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Kämpfer P, Nordmann P. Chromosome-encoded Ambler class A β-lactamase of Kluyvera georgiana, a probable progenitor of a subgroup of CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:4038–4040. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.4038-4040.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Decousser JW, Nordmann P. Insertion sequence ISEcp1B is involved in the expression and mobilization of a blaCTX-M β-lactamase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2938–2945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2938-2945.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Lartigue MF, Decousser JW, Nordmann P. ISEcp1B-mediated transposition of blaCTX-M in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:447–450. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.447-450.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeer U, Boettner A, Nordmann P, Wallmann J. Determination of the susceptibility of four cephalosporins as a screening method to identify CTX-M (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli in veterinary medicine. Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; 2007. p. Abstract C2-1527/133. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki Y, Shibata N, Doi Y, Arakawa Y. Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-2 β-lactamase in cattle, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:69–75. doi: 10.3201/eid1001.030219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Committee for Veterinary Medical Products, cefquinome. Summary reports. 1995 EMEA/MRL/005/95. [Google Scholar]