Abstract

The life cycles of apicomplexan parasites progress in accordance with fluxes in cytosolic Ca2+. Such fluxes are necessary for events like motility and egress from host cells. We used genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GCaMPs) to develop a cell-based phenotypic screen for compounds that modulate Ca2+ signaling in the model apicomplexan Toxoplasma gondii. In doing so, we took advantage of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor zaprinast, which we show acts in part through cGMP-dependent protein kinase (protein kinase G; PKG) to raise levels of cytosolic Ca2+. We define the pool of Ca2+ regulated by PKG to be a neutral store distinct from the endoplasmic reticulum. Screening a library of 823 ATP mimetics, we identify both inhibitors and enhancers of Ca2+ signaling. Two such compounds constitute novel PKG inhibitors and prevent zaprinast from increasing cytosolic Ca2+. The enhancers identified are capable of releasing intracellular Ca2+ stores independently of zaprinast or PKG. One of these enhancers blocks parasite egress and invasion and shows strong antiparasitic activity against T. gondii. The same compound inhibits invasion of the most lethal malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Inhibition of Ca2+-related phenotypes in these two apicomplexan parasites suggests that depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by the enhancer may be an effective antiparasitic strategy. These results establish a powerful new strategy for identifying compounds that modulate the essential parasite signaling pathways regulated by Ca2+, underscoring the importance of these pathways and the therapeutic potential of their inhibition.

Keywords: calcium, calcium intracellular release, drug screening, parasitology, protein kinase G (PKG), signal transduction

Introduction

Apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium spp., the causative agents of toxoplasmosis and malaria, require changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations to egress from host cells and move within the infected organism (1–6). These pathways therefore hold tremendous therapeutic potential, not only due to their importance in parasite biology but because of their divergence from similar pathways in host cells. Compounds targeting Ca2+ signaling in parasites have been shown to be effective antiparasitics (discussed below). However, few of the molecules involved in regulating Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling have been identified in parasites, and their interplay is only evident in live cells. This has created a need for new methods to study Ca2+ signaling pathways in apicomplexan parasites, with the hope of defining the essential components and identifying novel inhibitors.

The mechanisms for Ca2+ entry into the cytoplasm and the physiologically relevant sources of Ca2+ remain poorly defined in apicomplexan parasites. Ca2+ can be mobilized from the parasite's intracellular stores, or it can be drawn from the environment. Current evidence points toward intracellular stores being sufficient for parasites to move between cells (6–8), although virulence of T. gondii is enhanced by extracellular Ca2+ (9). The best studied of these intracellular stores is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).2 This organelle is a highly networked, dynamic structure (10) that has been shown to constitute multiple spatially independent Ca2+ stores in some cell types (11). Such compartmentalization has also been hypothesized to occur in T. gondii (4). Mammalian cells store Ca2+ in endosomes, lysosomes (12), and the Golgi (13), in addition to the ER (14). Some alveolates, like Paramecium, additionally contain a network of alveolar sacs that sequester Ca2+ in an ATP-dependent manner, with physiologically relevant affinities (15, 16). Whether the inner membrane complex, an apicomplexan structure homologous to alveolar sacs, also stores Ca2+ remains to be determined. Like many other eukaryotes, apicomplexans also possess acidic vacuoles known as acidocalcisomes that contain Ca2+ in complex with pyrophosphate and polyphosphates. This Ca2+ can be released pharmacologically, but the function of acidocalcisomes remains unclear in apicomplexans (17). A final acidic Ca2+ store described in T. gondii is the plantlike vacuole or vacuolar compartment. The plantlike vacuole is an acidic organelle that releases Ca2+ upon treatment with l-phenylalanine-naphthylamide (GPN), which in other systems causes ion leakage from lysosomal compartments (18). Although implicated in ionic homeostasis, these phenotypes have not been linked to the plantlike vacuole's function as a Ca2+ store (18). Due to the lack of characterized regulatable Ca2+ channels, it remains an open question which of these Ca2+ sources are involved in parasite motility and invasion.

Recent evidence suggests that PKG may play a role in regulating parasite Ca2+. In Plasmodium berghei, PKG has been proposed to influence Ca2+ homeostasis, thereby regulating egress from host cells. Activation of PKG leads to change in the levels of the lipid precursors of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3). This has been hypothesized to increase IP3, which causes release of Ca2+ from the ER through binding to the IP3 receptor, although such a channel remains to be identified in apicomplexan parasites (19). PKG is also known to regulate egress in T. gondii, although its effect on parasite Ca2+ has not been determined (20). In both parasites, PKG can be pharmacologically activated using the mammalian phosphodiesterase inhibitor zaprinast (20, 21). In Plasmodium, zaprinast treatment leads to an increase in cyclic GMP levels that presumably activates PKG (22). Further characterization of zaprinast's mechanism of action could therefore shed light on Ca2+ signaling.

Targeting the downstream effectors of Ca2+ signaling has been shown to hold therapeutic value against T. gondii. Compounds targeting Ca2+-dependent protein kinase 1, a regulator of egress and invasion, reduce proliferation in cell culture and cyst burden in the brains of T. gondii-infected mice (23, 24). Drugs targeting Ca2+-related processes are appealing not only because of this historical success but also because many proteins involved in parasite Ca2+ signaling are sufficiently divergent from their mammalian counterparts to enable the design of drugs with minimal off-target effects. For example, protein kinase G (PKG), which regulates egress, invasion, and motility in T. gondii and Plasmodium spp. (19, 20, 25, 26), is sufficiently different from mammalian PKG to be selectively inhibited (27). Similarly, the Ca2+-dependent protein kinases lack homologues in mammalian cells (28), making them attractive drug targets.

In this study, we use both chemical and genetic Ca2+ indicators to define the regulatory circuits that mediate Ca2+ release in T. gondii and identify small molecules that modulate this process. We determine the effect of T. gondii PKG on cytosolic Ca2+ following treatment with zaprinast and characterize the source of the Ca2+ released in this process as a neutral store distinct from the ER. Using genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators recently established in T. gondii (29), we develop a cell-based phenotypic screen that allows us to monitor Ca2+ signaling in live cells without the technical challenges of conventional chemical Ca2+ indicators. Using this platform, we have been able to identify, in an unbiased manner, compounds that interfere with Ca2+ signaling. In contrast to enzyme-based assays, this system enables us to probe a broader swath of parasite biology. Recent analysis indicates that such phenotypic screens are more likely to lead to clinically approved drugs than the far more prevalent molecular target-based approaches (30). Our screen identified two novel PKG inhibitors that abrogate the effect of zaprinast, as well as two compounds that increase cytosolic Ca2+ through an independent pathway. From the latter, one compound blocks invasion of both T. gondii and Plasmodium falciparum. Our results demonstrate the potential of this strategy to explore parasite Ca2+ signaling and identify new compounds with antiparasitic potential against multiple apicomplexan parasites.

Experimental Procedures

Strain Construction and Maintenance

Recombinant human T. gondii strain RH parasites were maintained in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 μg/ml gentamicin. PKG-T and PKG-M alleles were constructed as described previously (31). GCaMP5 was amplified from pCMV-GCaMP5G (32) with primers containing NsiI and PacI restriction sites (forward primer, 5′-gcg atg cat cct ttt tcg aca aaa tgg gtt ctc atc atc atc atc atc; reverse primer, 5′-gcg tta att aat cac ttc gct gtc atc att tg) and cloned directionally, replacing the CAT gene in pSAG1/2-CAT (33) to generate pSAG1-GCaMP5. Recombinant human parasites were co-transfected with pSAG1-GCaMP5 and pSAG1/2-CAT and selected with chloramphenicol (40 μm), and clones were isolated by limiting dilution. The GCaMP6f strains was similarly derived, as described previously (29). Both GCaMP strains were maintained under selection to prevent loss of the transgene. The GFP-expressing strain was kindly provided by Jeroen P. J. Saeij (34).

Store Activation and Cpd1 Inhibition Experiments with GCaMP6f

GCaMP6f-expressing T. gondii were suspended at 2 × 107 parasites/ml in basal Ca2+ buffer (140 mm NaCl, 10 mm potassium gluconate, 2.7 mm MgSO4, 2 mm glucose, 250 μm EGTA, 85 μm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.3) or extracellular Ca2+ buffer (140 mm NaCl, 10 mm potassium gluconate, 2.7 mm MgSO4, 2 mm glucose, 1 mm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.3), supplemented with 1% FBS when noted. For the Cpd1 inhibition experiments, parasites were suspended in Ringer's solution (115 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 3 mm NaH2PO4, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm glucose, 1% FBS). In all cases, 100 μl of suspended parasites were applied to each well of a Cell Carrier 96-well plate (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). For store activation experiments, parasites were incubated on ice for 5 min before the addition of Enh1 or Enh2 (10 μm final concentration), zaprinast (100 μm final), or DMSO (0.3% final) suspended in the same buffers as the parasites to which they were added. To examine the effect of Cpd1 on zaprinast or Enh1 treatment of GCaMP6-expressing parasites, fluorescence was recorded for 100 s before adding Cpd1 to a concentration of 1.2 μm. Fluorescence was recorded for an additional 300 s before treatment with 10 μm Enh1 or 100 μm zaprinast. Parasites were incubated on ice for 5 min before the addition of zaprinast to slow down the response and facilitate observation of peak fluorescence. Fluorescence was read with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 528 nm every 10 s in a BioTek Cytation 3. The assay plate was shaken for 1 s before each read.

Compound Screen

GCaMP5-expressing parasites were suspended in Ringer's solution at 4 × 107 parasites/ml, and 50 μl of parasites were applied to each well of a 96-well plate (Costar, catalog no. 3631). Parasites were treated with compounds from the GSK libraries PKIS and PKIS2 at 13.3 μm or 1.33% DMSO as a vehicle control and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 10 min. Parasites were then treated with 100 μm zaprinast or 0.1% DMSO as a vehicle control and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for an additional 4 min before measuring fluorescence with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 525 nm, respectively, on a SpectraMax M3 (Molecular Devices). Basal fluorescence, measured from untreated parasites, was subtracted from all values, and results were expressed as -fold change from parasites treated only with zaprinast. Z′ factors were determined from (i) parasites treated with zaprinast versus untreated parasites and (ii) parasites treated with a final concentration of 1 μm Cpd2 or a vehicle control followed by zaprinast, using the formula, Z′ = 1 − 3(σp + σn)/(|μp − μn|), where σp and σn indicate S.D. values of positive and negative controls, and μp and μn indicate the means of positive and negative controls, respectively.

In Vitro PKG Assays

Recombinant T. gondii PKG was expressed using a baculovirus system. Synthetic DNA coding for the protein was amplified and subcloned into the pFBOH-MHL vector, which confers an N-terminal His6 tag with a tobacco etch virus cleavage site. The resulting plasmid was transformed into DH10BacTM Escherichia coli competent cells to produce recombinant viral DNA. P3 viral stocks were used to infect Sf9 insect cells grown in HyQ SFX insect serum-free medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The culture was incubated at 27 °C and shaken at 100 rpm. After 60–72 h, the cells were harvested. The His-tagged T. gondii PKG samples were purified by affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography using an ÄKTAxpress system equipped with a SuperdexTM 200 10/300 column (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, Canada). In vitro kinase assays were performed using a PKG assay kit (CycLex) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Inhibitors were tested against 6.76 nm recombinant PKG, which was active within the linear range of the assay.

Structural Analysis

Structures of various protein kinases in complex with pyrazolopyridazine (PP) and oxindole derivatives were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (35) and aligned on the basis of their kinase domains. For the PP analysis, the CDK2 structures 3EID and 3EJ1 (36) and the p38 MAPK structure 3GCP (37) were aligned to the ERK2 structure 1WZY (38). For the oxindole analysis, the PDK1 structures 2PE0 and 2PE2 (39) and the Alk5 structure 2X7O were aligned to the Nek2 structure 2JAV (40).

Lactate Dehydrogenase Release Egress Assays

Confluent HFF monolayers in 96-well plates were infected with 5 × 104 parasites/well. The HFF monolayer was washed once with Ringer's solution ∼18 h later, and 50 μl of Ringer's solution was applied to each well. Drugs suspended in Ringer's solution were applied at 1.33 times the indicated concentrations. 1.33% DMSO in Ringer's solution was used as a vehicle control. Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 20 min, stimulated with 500 μm zaprinast or 0.5% DMSO (vehicle), and incubated again for an additional 5 min. The cells were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, before collecting 50 μl of each supernatant. The lactate dehydrogenase levels in the supernatant samples were quantified using the CytoTox 96 cytotoxicity assay (Promega) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Plaque Assays

T. gondii parasites were suspended in growth medium supplemented with Enh1, zaprinast, or DMSO alone at the indicated concentrations. The amount of DMSO in all treatment groups was normalized to 0.1%. Parasites were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 20 min before infecting HFF monolayers in 6-well plates using 3 ml carrying 100 parasites/well. Medium containing the highest concentration of each drug was also applied to HFF cells in the absence of parasites to assess the effects of the drugs on host cell viability. The parasites were allowed to plaque for 8 days before fixing with 70% ethanol and staining with 0.1% crystal violet.

Lytic Assays

Drugs were suspended at twice the indicated concentrations in growth medium and mixed with an equal volume of parasites at an initial concentration of 106 parasites/ml. The maximum concentration of DMSO was added as a vehicle control: 1% DMSO in comparisons with zaprinast and 0.013% in comparisons with Enh1. Parasites were preincubated with the compounds for 20 min at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and then 200 μl/well (105 parasites) was added to host cell monolayers in 96-well plates. Assay plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 days and then fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Absorbance at 590 nm was read as a measure of host cell lysis.

Cell-wounding Assays

Parasites suspended in Ringer's solution at 5 × 105 parasites/ml were pretreated with varying concentrations of zaprinast (as indicated) for 20 min at 37 °C with 5% CO2. 105 parasites/well were then applied to confluent host cell monolayers, and plates were centrifuged at 290 × g for 5 min. Following 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2, plates were centrifuged again at 500 × g for 5 min. 50 μl of supernatant were collected from each well, and lactate dehydrogenase was quantified using the CytoTox 96 cytotoxicity assay (Promega).

Video Microscopy Egress Assays

Host cell monolayers in Cell Carrier 96-well plates (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) were infected with 5 × 104 GFP-expressing parasites/well. 18 h postinfection, the medium was exchanged for Ringer's solution, and the intracellular parasites were treated with 10 μm Enh1, 500 μm zaprinast, or 0.5% DMSO. Images were acquired every 10 s for 30 min. To measure the effect of Enh1 on zaprinast and A23187-induced egress, the procedure was repeated, adding either 12.5 μm Enh1 or 0.13% DMSO and imaging for 10 min, before stimulation with 500 μm zaprinast or 1 μm A23187 (Calbiochem) and imaging for an additional 10 min. In all cases, images were acquired with a ×4 objective on a Cytation3 reader (BioTek) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 528 nm, respectively. Intact vacuoles were defined as objects of at least 78 μm2 with a circularity of at least 0.5, as determined in Fiji after default thresholding (41).

Video Microscopy

Parasites expressing GCaMP5 were transfected with p30-DsRed and used to infect host cell monolayers in 3-cm glass bottom dishes (MatTek). Approximately 20 h after infection, medium was exchanged for Ringer's solution, and parasites were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse Ti epifluorescence microscope, equipped with an enclosure heated to 37 °C. Images were acquired every 5 s for 10 min following the addition of zaprinast to a final concentration of 100 μm. To quantify changes in fluorescence, videos were analyzed in Fiji to measure the average fluorescence intensity in specific circular regions of interest 10 μm in diameter. To examine the effects of zaprinast and Enh1 on mammalian cells, 6 × 103 HeLa cells were seeded in each well of a Cell Carrier 96-well plate. Approximately 24 h later, HeLa cells were transfected with 100 ng of the pCMV-R-GECO (42) using Fugene (Promega) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were washed in Ringer's solution and then treated with 10 μm Enh1, 500 μm zaprinast, or 2 μm A23187. Images were acquired every 12 s for 30 min on a Cytation3 reader (BioTek) using an excitation wavelength of 531 and an emission wavelength of 593. Higher resolution videos were similarly acquired from HeLa cells seeded in 3-cm glass bottom dishes (MatTek) and transfected with 200 ng of pCMV-R-GECO per dish. Cells were treated with either 500 μm zaprinast or 10 μm Enh1 in Ringer's solution and imaged every 250 ms using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Videos were analyzed in Fiji using default thresholding for the red channel to determine the mean gray value in each slice for individual cells. Kymographs were constructed from videos of intracellular GCaMP6f-expressing parasites, following the same treatment as for the video microscopy egress assays, except half as many parasites were used to infect the monolayers, and a ×20 objective was used to acquire the images. Regions of interest were defined by outlining parasites in Fiji and measuring the mean fluorescence of each region over time.

Fura-2 Recordings

Tachyzoite loading with Fura-2/AM was done as described previously (17). Briefly, freshly lysed parasites were washed twice with buffer A (116 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 0.8 mm MgSO4, 5.5 mm d-glucose, and 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) and resuspended to a final density of 1 × l09 parasites/ml in loading buffer (buffer A plus 1.5% sucrose and 5 μm Fura-2/AM). The suspension was incubated for 26 min at 26 °C with mild agitation. Subsequently, the parasites were washed twice with buffer A to remove extracellular dye, resuspended to a final density of 1 × 109 parasites/ml in buffer A, and kept in ice. Parasites are viable for a few hours under these conditions. For fluorescence measurements, 2 × 107 parasites/ml were placed in a cuvette with 2.5 ml of Ringer's solution. Fluorescence measurements were done in a thermostatically controlled Hitachi F-7000 spectrofluorometer using the Fura-2 conditions for excitation (340 and 380 nm) and emission (510 nm). The Fura-2 fluorescence response to Ca2+ was calibrated from the ratio of 340/380-nm fluorescence values after subtraction of the background fluorescence of the cells at 340 and 380 nm, as described previously (43). The Ca2+ release rate is the change in Ca2+ concentration during the initial 20 s after the addition of compound.

Chemical Susceptibility of P. falciparum Egress and Erythrocyte Invasion

Blood stage P. falciparum parasites of strain 3D7 were obtained from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (Melbourne, Australia) and cultured as described previously (44). Parasites were maintained in O+ human erythrocytes (Research Blood Components, Boston, MA), at 2% hematocrit, in RPMI 1640 supplemented with HEPES (25 mm), hypoxanthine (50 mg/liter), sodium bicarbonate (2.42 mm), and Albumax (4.31 mg/ml). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C in microaerophilic atmospheric conditions (1% O2, 5% CO2, 94% N2) within modular incubator chambers.

To test the specific effects of Enh1 on egress of parasites from schizonts as well as erythrocyte invasion by liberated merozoites, mature schizont stage parasites were purified from 4 ml of blood stage culture (10–20% hematocrit) by centrifugation (930 × g, 15 min, low acceleration and deceleration) on 4 ml of a 60% Percoll cushion (45). Schizonts were retrieved from the medium supernatant-Percoll interface. After at least three washes in excess volumes of RPMI culture medium, schizonts were diluted with uninfected erythrocytes for a parasitemia of 3–5% and further supplemented with 2 μm Cpd2 to allow schizont maturation up to the point of egress (22). After 1–4 h at standard culture conditions, cultures were washed at least three times in excess RPMI culture medium to remove Cpd2 and added to 1 volume of Enh1 in RPMI or RPMI only (no drug) for a sample volume of 100 μl at 1% hematocrit. We similarly prepared samples of parasites supplemented with heparin (100 units/ml), a specific inhibitor of erythrocyte invasion (46), to assess the background signal for ring stage parasitemia (see below). We fixed samples (4% paraformaldehyde and 0.0075% glutaraldehyde in PBS (47)) at the outset of the experiment (untreated only) and after 1–2 h of incubation in standard culture conditions (all samples). After extensive washing in PBS and staining with SYBR Green I (1:1000 dilution in PBS; Invitrogen), schizont and ring stage parasitemia were measured by flow cytometry in the FITC channel as described previously (48, 49).

T. gondii Invasion Assays

Invasion assays were performed as described previously (20). Briefly, freshly lysed tachyzoites were preincubated for 10 min in varying concentrations of Enh1, keeping the total concentration of DMSO (vehicle) constant in all samples. HFF monolayers, seeded 48 h earlier, were infected at a multiplicity of infection of ∼10, and invasion was allowed to proceed for 10 min at 37 °C. Following fixation, intracellular parasites were enumerated by immunofluorescence and normalized to the number of host cells in a given field.

Results

Zaprinast Increases Cytosolic Ca2+ in a PKG-dependent Manner

Previous work has shown that zaprinast triggers T. gondii and P. falciparum egress in a PKG-dependent manner (20, 22). Because Ca2+ is a necessary second messenger during egress (8), we hypothesized that zaprinast might stimulate egress by increasing cytosolic Ca2+ in the parasite. To test this, we generated a strain that expressed the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5 (32) in the wild-type T. gondii recombinant human background. These parasites were transfected with a plasmid encoding a constitutively secreted fluorescent fusion protein, p30-DsRed, which accumulates in the parasitophorous vacuole before egress (50). This second sensor enabled us to visualize permeabilization of the parasitophorous vacuole, which has been demonstrated to occur via the Ca2+-regulated secretion of a perforin-like protein (50). Human fibroblasts infected with recombinant human GCaMP5 were treated with zaprinast and monitored by live video microscopy. Zaprinast elicited a rapid increase in fluorescence compared with the vehicle alone, which was followed by a second, less intense peak of fluorescence (Fig. 1, A and B). This led to permeabilization of the vacuole membrane, as indicated by diffusion of DsRed, and subsequent egress of the parasites from the host cell (supplemental Video S1).

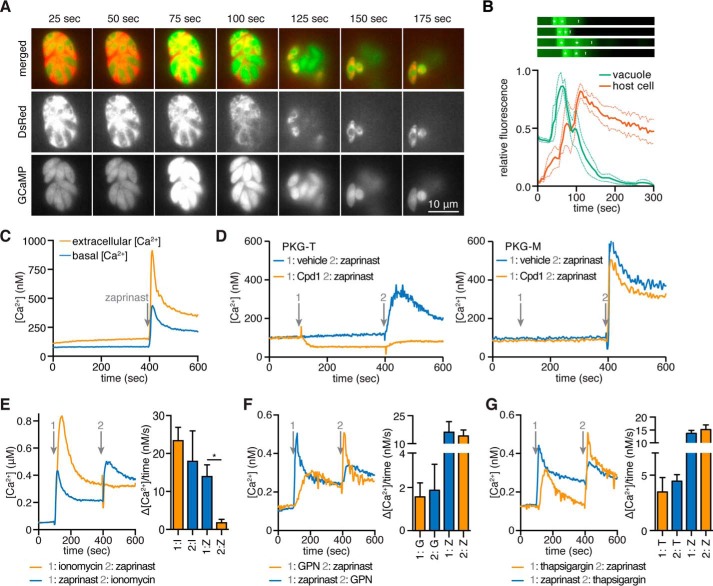

FIGURE 1.

Zaprinast raises cytosolic Ca2+ through the activation of PKG. A, video microscopy of intracellular parasites expressing both GCaMP5 and constitutively secreted DsRed, following the addition of zaprinast at 0 s. B, GCaMP5 fluorescence in the region of the parasitophorous vacuole (green) or DsRed fluorescence in adjacent areas of the infected host cell (red) following the addition of zaprinast. Results shown are mean ± S.E. for four experiments. Kymographs for GCaMP5 fluorescence in all four experiments are shown to indicate times of peak fluorescence (white asterisks) relative to the initiation of egress from the region (white vertical lines). C, intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, monitored over time, for wild-type parasites loaded with Fura-2/AM, suspended in buffer containing extracellular (1.8 mm) or basal (100 nm) free Ca2+, and stimulated with 100 μm zaprinast at 400 s. D, similar measurements were performed for PKG-M and PKG-T parasites loaded with Fura-2/AM and suspended in basal Ca2+. Cpd1 or vehicle was added at 100 s, and zaprinast was added at 400 s, as indicated. E–G, intracellular calcium concentrations from parasites loaded with Fura-2/AM and then treated with zaprinast, ionomycin, GPN, or thapsigargin at 100 s (1) and 400 s (2), as indicated. Traces are representative of three independent experiments. Bar graphs report the change in cytosolic calcium over 20 s following the addition of each drug. Results shown are mean ± S.E. (error bars). Z, zaprinast; I, ionomycin; G, GPN; T, thapsigargin; *, p < 0.05; one-tailed t test.

To determine whether the zaprinast-induced increase in Ca2+ represented release of intracellular stores or Ca2+ entry, we loaded wild-type parasites with the ratiometric Ca2+ indicator Fura-2/AM and stimulated them with zaprinast in buffers containing either a basal Ca2+ concentration (100 nm free Ca2+) or one resembling the extracellular environment (1.8 mm). We found that cytosolic Ca2+ increased in response to zaprinast under both conditions (Fig. 1C), although the response was magnified in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. This indicates that zaprinast-mediated Ca2+ mobilization occurs through release of intracellular stores, which may enhance Ca2+ entry, as has been reported for other agonists capable of releasing intracellular stores (9).

Compound 1 (Cpd1), a specific inhibitor of apicomplexan PKG (25), blocks zaprinast-induced egress (20). To determine whether zaprinast's effect on parasite Ca2+ depends on PKG, we measured the response to zaprinast after Cpd1 treatment. Sensitivity of apicomplexan PKG to Cpd1 relies on the identity of a residue at the base of the ATP-binding pocket known as the gatekeeper (25). We therefore used strains engineered to express PKG with either the wild-type threonine or a bulky methionine gatekeeper residue that renders PKG refractory to Cpd1 inhibition (31). These strains were loaded with Fura-2/AM, treated with Cpd1 or vehicle, and then stimulated with zaprinast. Parasites treated with vehicle responded to the addition of zaprinast with a sharp Ca2+ spike. The addition of Cpd1 did not change the response of the insensitive PKG-M strain. However, the Ca2+ spike was severely diminished by Cpd1 in the sensitive PKG-T strain, indicating the need for PKG in this process (Fig. 1D). We also observed a slight decrease in the cytosolic Ca2+ level of the PKG-T strain after Cpd1 treatment, perhaps indicating that PKG regulates the basal Ca2+ level in addition to enhancing it before egress.

Zaprinast Mobilizes a Neutral, SERCA-independent Ca2+ Store

To further characterize the source of zaprinast-mobilized Ca2+, we assessed the involvement of various Ca2+ storage organelles. We loaded parasites with Fura-2/AM and suspended them in a buffer containing basal Ca2+ and then added the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin. Binding of ionomycin to Ca2+ is pH-dependent and falls to negligible levels below pH 7 (51). Ionomycin has therefore been used to specifically mobilize neutral Ca2+ stores in both mammalian cells (52) and T. gondii (17). We observed a peak in cytosolic Ca2+ levels following ionomycin treatment, indicating that Ca2+ had been mobilized from neutral stores. Subsequent treatment with zaprinast did not produce an additional Ca2+ peak, indicating that the zaprinast-mobilized store had already been depleted by ionomycin. In contrast, treating parasites with zaprinast followed by ionomycin produced a Ca2+ spike in response to each compound. These results were corroborated by analyzing the rate of Ca2+ release during the 20 s that followed the addition of each compound (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these results indicate that the zaprinast-mobilized store comprises a subset of the ionomycin-mobilized stores and as such is predicted to be neutral.

To further rule out acidic Ca2+ stores, we treated parasites with GPN before or after the addition of zaprinast. GPN is specifically hydrolyzed in lysosomal compartments, leading to their leakage, as has been shown for the plantlike vacuole in T. gondii (18). As predicted by mobilization with ionomycin, the zaprinast-mobilized store was independent from this acidic compartment (Fig. 1F).

The ER is the major neutral Ca2+ store in many organisms (53). Thapsigargin is an inhibitor of the Ca2+ reuptake pump SERCA, which partially localizes to the ER in extracellular T. gondii tachyzoites (54). We treated parasites with thapsigargin before or after the addition of zaprinast and found that zaprinast mobilized Ca2+ with the same efficiency regardless of the treatment order. The independence of the zaprinast- and thapsigargin-mobilized stores was evident in the rate of Ca2+ release following each treatment (Fig. 1F). These results indicate either that zaprinast mobilizes a neutral store that is separate from the ER or that the ER is segmented into SERCA-dependent and SERCA-independent Ca2+ stores, as has been hypothesized (4).

Identifying Small Molecules That Modulate Parasite Ca2+

Despite its central importance during infection, few compounds have been demonstrated to specifically interfere with the Ca2+ signaling pathways of apicomplexan parasites. Compounds that modulate Ca2+ signaling can have clinical value as well as being useful in research. We predicted that the zaprinast response measured in GCaMP5-expressing parasites could form the basis for a phenotypic screen. Such a screen would benefit from the known importance of Ca2+ signaling in parasite biology along with the reported success rate of cell-based phenotypic assays. We designed a screen wherein extracellular GCaMP5-expressing parasites were pretreated with compounds for 10 min before stimulation with zaprinast, and parasite fluorescence was measured 4 min later. We expected that compounds that interfered with the zaprinast response would reduce fluorescence. We calculated a Z′-factor for this screen to determine its dynamic range and suitability to high throughput screening. To do so, we compared zaprinast-treated parasites to untreated parasites or those pretreated with the PKG inhibitor Compound 2 (Cpd2) (55). These scenarios yielded Z′-factors of 0.58 and 0.55, respectively, well above the 0.5 Z′-factor considered acceptable for high throughput screening (56). This phenotypic screen is therefore suitable for analyzing large libraries of compounds to identify compounds interfering with parasite Ca2+ signaling (Fig. 2A).

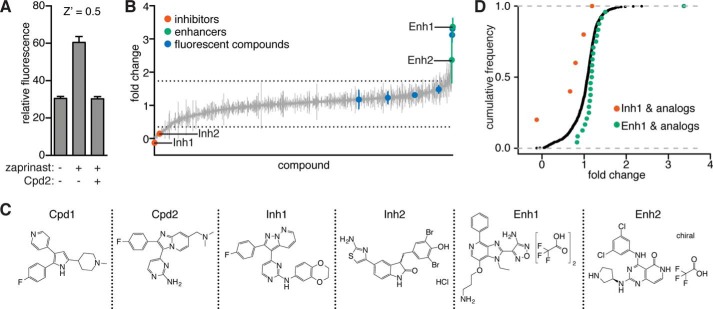

FIGURE 2.

Compound screen identifies modulators of zaprinast-induced Ca2+ signaling. A, GCaMP5-expressing parasites pretreated with Cpd2 or a vehicle control were stimulated with zaprinast or a vehicle control, and fluorescence was measured to determine a Z′ score for a zaprinast-based screen for Ca2+ modulators. B, GCaMP5-expressing parasites were pretreated with 823 compounds from the PKIS libraries. Fluorescence was measured after zaprinast stimulation. Results are -fold change from zaprinast alone after background subtraction. Compounds that fluoresced independently are indicated (blue) along with selected enhancers (Enh; green) and inhibitors (Inh; red). The mean ± S.D. (error bars) of two experiments is shown, and dashed lines indicate two S.D. values above and below the mean of all compounds. C, structures of Enh1, Enh2, Inh1, and Inh2 as well as the known PKG inhibitors: Cpd1 and Cpd2. D, cumulative frequencies of screen values for all compounds (black), Inh1 and its analogs (red), or Enh1 and its analogs (green).

We obtained the compound libraries published kinase inhibitor sets PKIS1 (57) and PKIS2 (unpublished), from GlaxoSmithKline and applied our phenotypic screen to the 823 ATP mimetics represented in these collections (Fig. 2B and supplemental Table S1). The compounds were screened at a single 10 μm dose with two biological replicates. We identified 37 putative inhibitors and 14 putative enhancers, defined as compounds that resulted in fluorescence readings that were more than two S.D. values below or above the mean of all compounds, respectively. Compounds that interfered with accurate measurement of GCaMP5 fluorescence, including two putative enhancers, were identified and excluded from subsequent experiments.

We wondered whether we could identify classes of molecules that inhibit or enhance Ca2+ mobilization. To this end, we examined analogs of the most potent enhancer and inhibitor, which we here refer to as Enh1 (PKIS: GSK260205A) and Inh1 (PKIS: GW827099X) (Fig. 2C). Compounds with the same core structure as Enh1 generally produced a -fold change in fluorescence of >1 in our screen, indicating that parasite fluorescence was greater in the presence of such compounds than with zaprinast alone (Fig. 2D and supplemental Fig. S1). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test comparing the values obtained from all compounds with those obtained from the Enh1 analogs revealed a significant difference (p = 0.0042) (Fig. 2D). The combination of a phenyl group at the R1 position and a 3-aminopropyloxy group at the R3 position, as found in Enh1, appeared to produce a particularly effective enhancer; compounds having either group without the other produced only a mild effect. A similar analysis of Inh1 analogs revealed that these compounds tended to inhibit zaprinast-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Fig. 2D and supplemental Fig. S2). The fluorophenyl group in the R1 position of Inh1 may be responsible for this compound's strong inhibitory effect (as discussed below). This 4-fluorophenyl is also found in Cpd1 and Cpd2. No other R1 side group produced a similarly strong response, although an analogue containing a trifluoromethyl group at the R1 position elicited the second largest response in the group. In summary, although Enh1 and Inh1 are unique within the set of compounds tested for their abilities to augment and repress cytosolic Ca2+, their core structures appear to be generally well suited to these purposes. Indeed, further exploration of these scaffolds could lead to the identification of improved modulators of parasite Ca2+ signaling.

Two Inhibitors Target PKG Using Distinct Chemical Scaffolds

Because known PKG inhibitors could suppress zaprinast-induced Ca2+ release (Fig. 1D), we hypothesized that the newly identified compounds could act in a similar manner. We tested the effects of Inh1 and Inh2 (compound GW407323A from the screen) on the in vitro activity of recombinant T. gondii PKG. Both compounds inhibited PKG activity with IC50 values of 580 nm for Inh1 and 670 nm for Inh2 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that PKG inhibition is a plausible explanation for their activity. Furthermore, neither inhibitor showed appreciable activity against human PKG or related AGC kinases (57), demonstrating selectivity for the parasite enzyme.

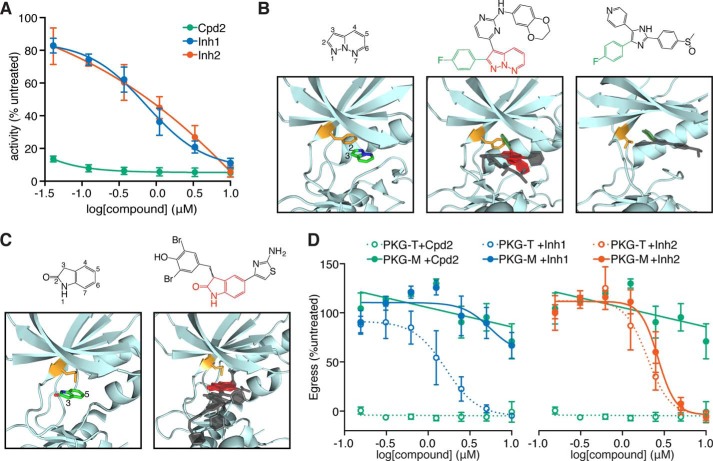

FIGURE 3.

PKG inhibitors display distinct modes of inhibition. A, activity of recombinant PKG in the presence of increasing concentrations of Inh1, Inh2, or the PKG inhibitor Cpd2. B, binding of PP derivatives like Inh1 to protein kinases orients the C2 position toward the gatekeeper residue (orange). Left, the PP scaffold's orientation for a disubstituted PP in complex with CDK2. Middle, the structure of Inh1 is highlighted to indicate the PP scaffold (red) and the C2 fluorophenyl group (green). Two other similar compounds from other kinase structures are superimposed over the CDK2 structure in complex with its inhibitor, all showing a similar positioning of the PP scaffold. Right, human p38 MAPK with a trisubstituted monocyclic heterocycle oriented similarly as the PP scaffold and extending a fluorophenyl group in the direction of the gatekeeper. C, oxindole derivatives bind to protein kinases in a manner that orients their C2 and C5 positions away from the gatekeeper. Left, oxindole scaffold of a derivative in complex with NEK2. Right, the oxindole scaffold of Inh2. Two other similar compounds from other kinase structures have been superimposed on the structure of NEK2 with its inhibitor. D, zaprinast-induced egress of parasites carrying Cpd2-sensitive (PKG-T) or resistant (PKG-M) alleles of PKG, following pretreatment with Inh1, Inh2, or Cpd2. Results shown are mean ± S.E. (error bars) for n = 3 independent experiments.

The two inhibitors are derivatives of distinct bicyclic heterocyclic scaffolds with proven activity against protein kinases. Inh1 is a PP with substitutions in the C2 and C3 positions (Fig. 3B). Several available kinase structures display a similar orientation of the PP scaffold in the ATP-binding pocket, with the C3 position engaging the hinge region and the C2 position oriented toward the gatekeeper residue. The structures of two such inhibitors complexed with human CDK2 demonstrate the proximity of the C2 position to the bulky phenylalanine-gatekeeper residue (Fig. 3B, middle). Substitutions at this position decreased the activity of these inhibitors presumably due to steric clash with the gatekeeper (36). The 4-fluorophenyl group in the C2 position of Inh1 is therefore expected to restrict binding of the inhibitor to kinases with relatively small gatekeepers, like the threonine found in T. gondii PKG. This type of binding is evident in the structure of p38 MAPK with a ligand similar to Inh1 (SB203580, a monocyclic heterocycle rather than a bicyclic one) that extends the 4-fluorophenyl functional group into the hydrophobic pocket created by a threonine gatekeeper (37) (Fig. 3B, right). Furthermore, the related human kinase ERK2, normally resistant to SB203580, can be rendered sensitive to this inhibitor by mutation of its gatekeeper glutamine to either an alanine or a threonine (58). This strongly suggests that a small gatekeeper is required to accommodate heterocycles with substitutions similar to those found on Inh1.

Inh2 is an oxindole derivative, with substitutions at the C3 and C5 positions (Fig. 3C). Disubstituted and trisubstituted oxindoles are well studied protein kinase inhibitors. Several structures are available of kinases in complex with such inhibitors. In every instance, the oxindole is positioned such that the 2-oxygen and the nitrogen of the bicyclic scaffold engage the hinge residues (Fig. 3C, left). This configuration leaves the C3 and C5 positions pointing away from the binding pocket. Although the C6 substituent is inward pointing, it does not approach the direction of the gatekeeper. The binding configuration of oxindole derivatives is highly consistent across several different kinase structures, suggesting that Inh2 (a 3,5-disubstituted oxindole) is likely to be gatekeeper-independent.

To determine whether these inhibitors could interfere with other PKG-dependent processes, we next assessed their ability to block zaprinast-induced egress. We directly tested the structural predictions regarding the effect of the gatekeeper on Inh1, but not Inh2, by performing these experiments with the PKG-M and PKG-T strains. We measured zaprinast-induced egress by lactate dehydrogenase release from host cells infected with either strain (Fig. 3D). As expected, PKG-T parasites did not egress after Cpd2 treatment, whereas the refractory PKG-M strain egressed similarly to vehicle-treated parasites. Both Inh1 and Inh2 reliably reduced egress relative to vehicle-treated parasites. The similar potencies of these compounds in vivo and in vitro are consistent with inhibition of PKG being the primary mechanism through which Inh1 and Inh2 block egress (Fig. 3D). As predicted from our structural analysis, Inh1 worked in a gatekeeper-dependent manner, reducing egress from cells infected with PKG-T parasites with an IC50 of 1.3 μm but leaving PKG-M parasites unaffected. In contrast, Inh2 reduced egress from cells infected with either strain, exhibiting an IC50 of 2.5 μm for PKG-T and 3.5 μm for PKG-M. These results were satisfying because we were able to recover inhibitors with distinct scaffolds and modes of inhibiting an enzyme known to be involved in the zaprinast response. Identification of two novel PKG inhibitors through a screen of only 823 compounds demonstrates the power of our approach to identify compounds with biological effects in pathways critical to parasite survival.

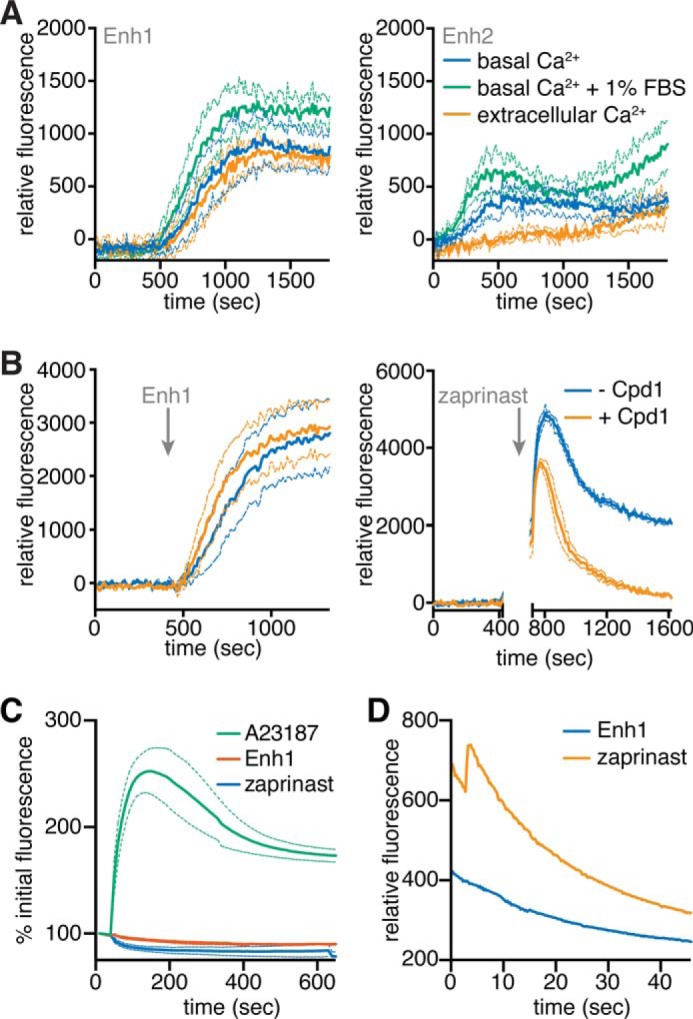

Two Enhancers Directly Release Intracellular Ca2+ Stores

Having shown that a screen for modulators of zaprinast-induced Ca2+ mobilization reveals novel PKG inhibitors, we turned our attention to Enh1 and another putative enhancer: Enh2, or GSK2188764A (Fig. 2C). During the course of this study, the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f became available. Because GCaMP6f has a broader dynamic range and faster kinetics than GCaMP5 (59), we used GCaMP6f throughout much of this study. We tested whether the enhancers could increase parasite Ca2+ independently of zaprinast. Indeed both enhancers could mobilize Ca2+ on their own, although they did so with significantly slower kinetics than zaprinast (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Enh1 and Enh2 mobilize intracellular Ca2+ stores. A, GCaMP6-expressing parasites suspended in buffer supplemented with either extracellular (1 mm) or basal (100 nm) Ca2+ concentrations, with or without 1% FBS, and treated with 10 μm Enh1 or Enh2 at time 0. B, GCaMP6-expressing parasites treated with 1 μm Cpd1 or vehicle at 100 s and then with 10 μm Enh1 or 100 μm zaprinast at 400 or 750 s, respectively. A gap indicates incubation on ice before the addition of zaprinast, in order to capture the peak of the response. Measurements represent fluorescence after the subtraction of background obtained from samples treated with Cpd1 or vehicle, as indicated. Results shown are mean ± S.E. (error bars) for n = 3 independent experiments. C and D, intensity of R-GECO-expressing HeLa cells treated with Enh1, zaprinast, or A23187 over 10 min (C) or acquired at a faster rate for 1 min (D).

To determine the source of the Ca2+ mobilized by the enhancers, we suspended parasites in buffers containing extracellular (1 mm) or basal (100 nm) levels of free Ca2+, treated these parasites with 10 μm Enh1 or Enh2, and monitored GCaMP6f fluorescence (Fig. 4A). Enh1 increased fluorescence under both conditions, indicating that it mobilizes intracellular stores. Surprisingly, we observed only weak mobilization of Ca2+ in response to Enh2 under both conditions. Because the original screen was performed in buffer containing 1% FBS, we tested the effect of this component. The addition of 1% FBS increased Enh2-mediated Ca2+ mobilization. We interpreted this to mean that Enh2 requires a cofactor found in FBS. Because the activity of Enh2 is relatively weak and depends on specific conditions, we focused subsequent experiments on Enh1.

We wondered whether, like zaprinast, Enh1 functions through PKG to increase parasite Ca2+. Significant overlap in the emission spectra of Enh1 and Fura-2 prevented us from using this ratiometric indicator. However, we were able to use GCaMP6f to make semiquantitative measurements. We recorded fluorescence from GCaMP6f-expressing parasites treated with Cpd1 or vehicle control, followed by stimulation with Enh1 or zaprinast. To record the peak fluorescence induced by zaprinast, we had to incubate parasites on ice before stimulation so as to slow down the response. In contrast to the zaprinast response, Cpd1-treated parasites responded to Enh1 in the same manner as vehicle-treated parasites, indicating that Enh1 does not act through PKG. Although Cpd1 accelerated the return to basal Ca2+ levels following zaprinast treatment, it only partially decreased the initial Ca2+ spike induced by zaprinast (Fig. 4B). This is reminiscent of results obtained from Fura-2-loaded parasites, where the increase in Ca2+ following zaprinast could never be fully suppressed by PKG inhibition (Fig. 1D).

We wondered whether zaprinast or Enh1 could induce Ca2+ fluxes in mammalian cells. We transfected HeLa cells with the plasmid CMV-R-GECO (42), which encodes a variation of the GCaMP Ca2+ indicators under the mammalian CMV promoter. We treated these transfected cells with zaprinast, Enh1, or, as a positive control, the Ca2+ ionophore A23187. Video microscopy revealed that R-GECO-expressing HeLa cells increased fluorescence in response to A23187 but that neither zaprinast nor Enh1 produced a significant change (Fig. 4C). Given that zaprinast is known to inhibit phosphodiesterases in mammalian cells (60), we considered that these drugs could be having a subtle effect that was below our limit of detection. We therefore repeated the assay with greater spatial and temporal resolution. We observed a slight increase in R-GECO fluorescence in response to zaprinast during the first 10 s of treatment. However, Enh1 had no effect on host cell Ca2+ (Fig. 4D), indicating that the effects of Enh1 are specific to Ca2+ signaling in the parasite.

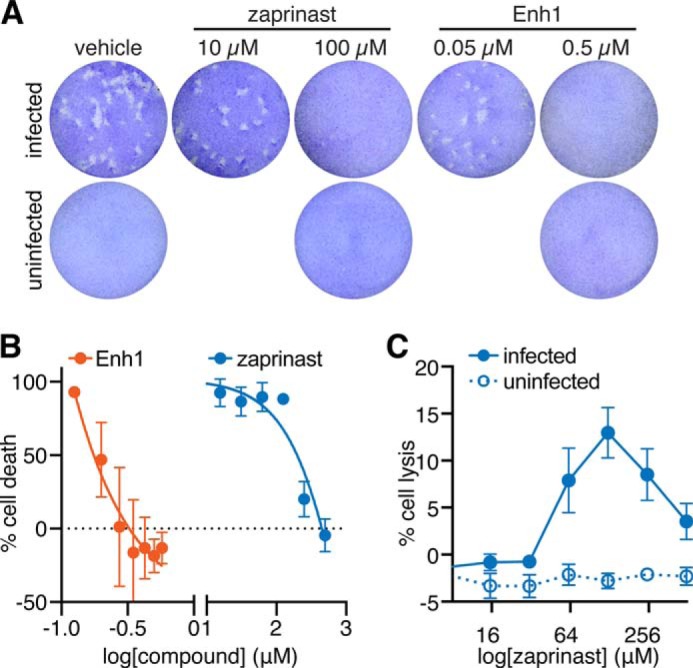

Enh1 Inhibits T. gondii Survival

Zaprinast and related phosphodiesterase inhibitors were recently shown to block T. gondii proliferation in human fibroblasts (61). Altering Ca2+ levels using ionophores has also been shown to affect parasite viability (62). We therefore hypothesized that Enh1 would similarly inhibit survival of T. gondii. We tested the effect of these compounds using plaque assays as an indication of parasite survival following treatment with Enh1 or zaprinast. Plaque formation was inhibited by zaprinast and Enh1 at 100 and 0.5 μm, respectively, whereas 10-fold lower concentrations allowed normal plaque formation similar to vehicle alone (Fig. 5A). These results for zaprinast agree with previously published work (61). In order to determine the inhibitory concentrations of these compounds more precisely, we performed lytic assays in which host cells were exposed to parasites pretreated with varying concentrations of zaprinast or Enh1, and the degree of host cell lysis was assessed by crystal violet staining of the monolayer, 3 days later. Enh1 showed a steep dose response, with 350 nm completely inhibiting parasite-induced cell death, and an EC50 of 180 nm. In contrast, 500 μm zaprinast was required to cause complete inhibition of parasite-induced cell death, and the IC50 of zaprinast was 200 μm (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Enhancers of Ca2+ mobilization show antiparasitic activity. A, plaque formation in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Enh1 or zaprinast. The drug concentrations indicated did not affect host cell survival. B, dose-dependent effect of Enh1 and zaprinast on parasite viability, assayed by monolayer disruption, 3 days postinfection, at the indicated drug concentrations. Results shown are mean ± S.E. (error bars) for n = 3 independent experiments. C, host cell lysis following 1 h of infection in the presence of varying zaprinast concentrations.

We noticed the discrepancy between the amount of zaprinast required to kill T. gondii in plaque assays (100 μm) and the amount needed in lytic assays (500 μm). Because a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ stimulates parasite motility (2), we wondered if the movement of T. gondii in response to concentrations between 100 and 500 μm might mechanically wound and kill host cells, which would be indistinguishable from parasite survival in the lytic assay. We tested this hypothesis by incubating host cell monolayers with parasites pretreated with various concentrations of zaprinast and then measuring lactate dehydrogenase release from host cells. We found that treatment with 64–510 μm zaprinast resulted in host cell lysis, with a maximal effect at 130 μm. Host cell lysis was not observed with zaprinast in the absence of T. gondii (Fig. 5C). Due to the lower multiplicity of infection used in plaque assays compared with lytic assays, host cells in plaque assays would be unlikely to experience observable cell wounding. We therefore expect the plaque assays to provide a more accurate measure of zaprinast's antiparasitic activity.

Enh1 Induces Asynchronous Ca2+ Fluxes

We thought it likely that the plaquing defect caused by Enh1 was related to the Ca2+ disregulation induced by this compound. We therefore characterized the Ca2+ response to Enh1 in more detail. We recorded videos of intracellular GCaMP6f-expressing parasites treated with Enh1 and compared the result with zaprinast treatment, which we have shown induces egress. We observed GCaMP6f activity in both cases, indicating that Enh1 can act on intracellular parasites. However, the profiles of zaprinast and Enh1-mediated Ca2+ mobilization were remarkably different. Whereas zaprinast induced a fast, strong Ca2+ peak (Fig. 6A and supplemental Video S2), Enh1 elicited a slow, asynchronous effect in which some parasites appeared to experience multiple Ca2+ fluxes of similar magnitudes over the course of several minutes (Fig. 6A and supplemental Video S3). The response to these compounds was similar in extracellular parasites (data not shown).

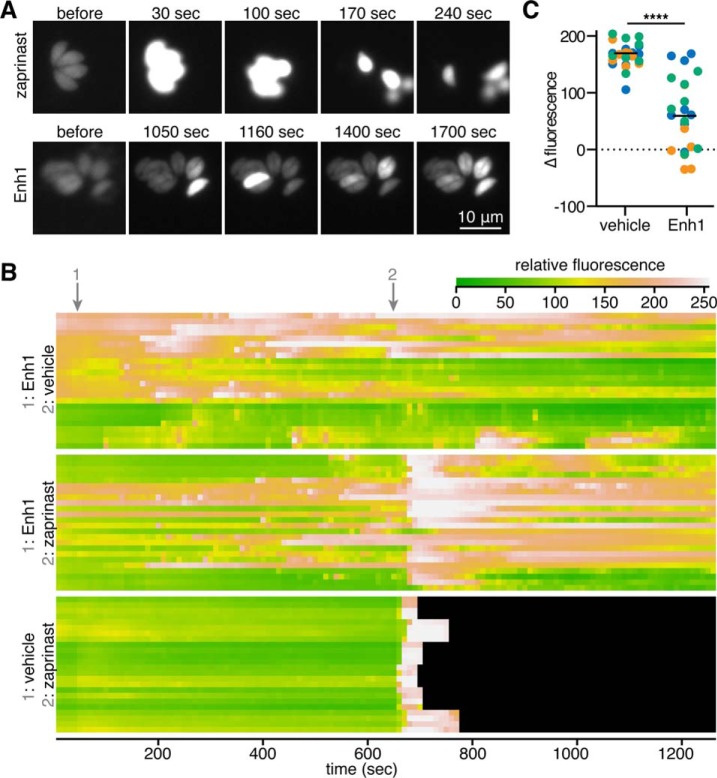

FIGURE 6.

Enh1 elicits asynchronous cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes and blocks zaprinast-induced egress. A, video microscopy of GCaMP6f-expressing parasites treated with Enh1 or zaprinast. Time after the addition of the compound is indicated. Different times were used to capture the fast and slow responses of zaprinast and Enh1, respectively. B, kymographs illustrate average fluorescence intensities of individual parasites, per row, during the course of the treatment indicated. Black indicates that parasites egressed from vacuoles. C, change in fluorescence of the parasites illustrated in B over the 40 s following the addition of zaprinast. Measurements from each biological replicate are colored separately. Mean change for each group is indicated with a horizontal line. ****, p < 0.0001, two-tailed t test.

We generated kymographs illustrating the responses of individual GCaMP6f parasites to Enh1. Wondering whether pretreatment with Enh1 would affect the ability of parasites to respond to other Ca2+ agonists, we treated some of these parasites with zaprinast as well (Fig. 6B). The sporadic flashes of Ca2+ triggered by Enh1 were recapitulated, and all vehicle-treated parasites experienced an increase in Ca2+ immediately after the addition of zaprinast. However, Enh1-treated parasites varied in their responses to zaprinast, exhibiting asynchronous Ca2+ fluxes and inconsistent magnitudes in their Ca2+ increases. In rare cases, Ca2+ concentrations in Enh1-treated parasites even dropped upon zaprinast treatment. We quantified the changes in fluorescence of individual parasites over the 40 s following zaprinast addition and observed a more varied and overall diminished response to zaprinast in Enh1-treated parasites (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results suggest that Enh1 may partially deplete the Ca2+ stores mobilized by zaprinast.

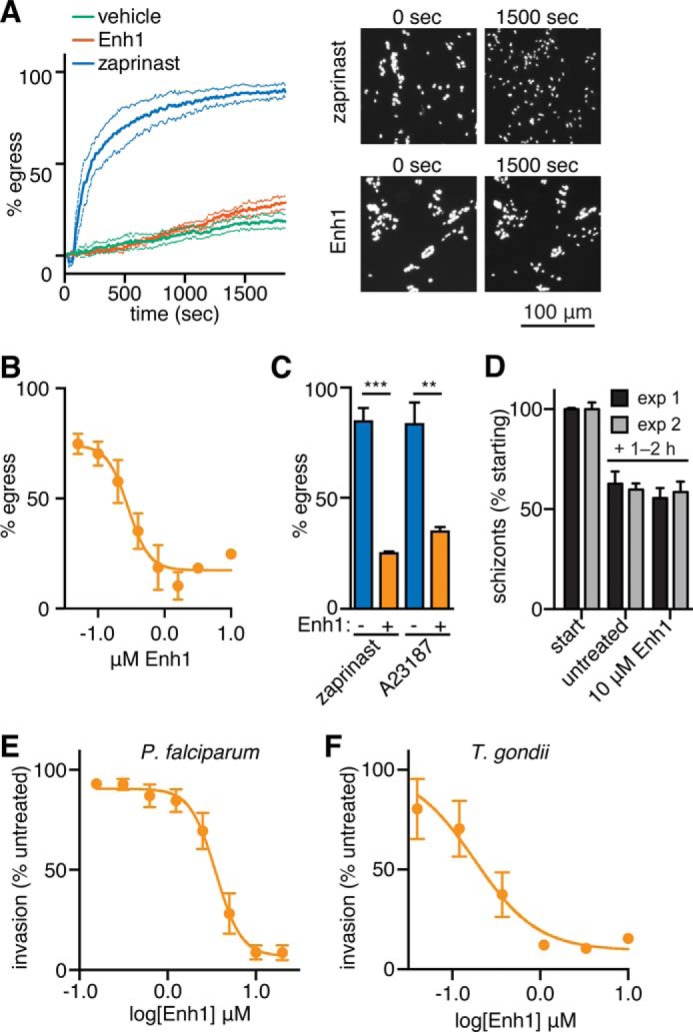

Enh1 Blocks Ca2+-related Phenotypes in T. gondii and P. falciparum

While examining Enh1-treated parasites, we noticed that this compound did not induce egress and in fact suppressed egress in response to zaprinast (Fig. 6C). To confirm these effects, we treated intracellular GFP-expressing parasites with Enh1 and quantified the number of intact vacuoles at various times after treatment, using fluorescence to monitor the infection using automated image analysis. This assay is capable of directly measuring egress for hundreds of vacuoles per sample. Surprisingly, despite its effects on extracellular parasites, Enh1 failed to stimulate egress beyond the spontaneous egress observed in the vehicle control. In contrast, zaprinast treatment resulted in ∼90% of vacuoles egressing within 30 min (Fig. 7A), as described previously (20). We then examined the effect of a 10-min Enh1 pretreatment and found that it robustly blocked zaprinast-induced egress. Analysis of the dose-dependent inhibition of egress by Enh1 revealed an EC50 of 290 nm, within the range of concentrations that inhibit plaque formation (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that the antiparasitic activity of Enh1 is mediated by its inhibition of parasite egress.

FIGURE 7.

Enh1 blocks egress Ca2+-related phenotypes in T. gondii and P. falciparum. A, egress of intracellular parasites treated with zaprinast, Enh1, or a vehicle control. The number of intact vacuoles was monitored by live microscopy over 30 min. Representative images before and after treatment are shown. B, dose-dependent inhibition of zaprinast-induced egress following pretreatment with Enh1 or vehicle. C, Enh1 inhibition of egress induced by either zaprinast or A23187. Results shown are mean ± S.E. (error bars) for n = 3 independent experiments. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01. D–E, schizonts were released from Cpd2 arrest immediately preceding the addition of Enh1. D, after 1–2 h, the remaining schizonts (mean ± S.D. for three technical replicates) were counted and normalized to their initial abundance (3.6 and 5.4% in each experiment, respectively). E, Enh1 blocks invasion of erythrocytes by P. falciparum, measured 1–2 h following release from Cpd2, as assessed from the ring stage parasitemia. Mean invasion ± S.E. is expressed as a percentage of invasion without drug (9.5 and 8.1% in each experiment, respectively). Background was assessed using heparin as a specific blocker of invasion and was comparable with the signal observed with saturating concentrations of Enh1. F, dose-dependent inhibition of T. gondii invasion following 10-min pretreatment of parasites before invasion. Results shown are mean ± S.E. for n = 3 independent experiments.

We wondered whether we could generalize the Enh1-associated egress defect beyond zaprinast-induced egress. We therefore tested the ability of Enh1 to block egress induced by the Ca2+ ionophore A23187. Enh1 also produced a significant block on A23187-induced egress (Fig. 7C), demonstrating that its effects on parasite Ca2+ signaling extend to a variety of agonists.

We tested whether Enh1 also affects other apicomplexan parasites that use Ca2+-based signal transduction. Asexual, blood stage Plasmodium parasites undergo Ca2+-dependent egress from infected erythrocytes, followed by Ca2+-dependent invasion into new erythrocytes (6, 63). To assess the effect of Enh1 on these processes at the relevant developmental stage, we allowed purified schizonts to complete their intracellular maturation while blocked with Cpd2 from rupturing and egressing (22). We administered Enh1 to parasites immediately following washout of Cpd2. After allowing 1–2 h of incubation with the compound, we measured egress and reinvasion using a flow cytometry-based assay that distinguishes schizonts from recently invaded ring stage parasites (49). Whereas Enh1 does not reduce parasite egress at concentrations up to at least 10 μm (Fig. 7D), the compound completely blocks invasion within the tested range (IC50 = 3.2 μm) (Fig. 7E). Wondering whether Enh1 could also inhibit invasion in T. gondii, we incubated tachyzoites with varying doses of Enh1 for 20 min and tested their ability to infect host cells. As in P. falciparum, Enh1 strongly inhibited T. gondii invasion (Fig. 7F). Furthermore, the IC50 of Enh1 in the invasion assay was 180 μm, similar to that in the egress assay, arguing for a common mechanism for the effect of Enh1 on both Ca2+-related phenotypes. In summary, Enh1 modulates Ca2+-dependent processes in diverse apicomplexan parasites.

Discussion

Ca2+ signaling plays a central role in apicomplexan biology, yet few of the components that regulate Ca2+ uptake and release have been identified. In this study, we extend our understanding of these processes by demonstrating that PKG activity is needed for the robust Ca2+ response elicited by phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Furthermore, we determine the source of Ca2+ to be distinct from other previously described stores. We use this phenomenon as the basis of a phenotypic screen that allowed us to identify several novel inhibitors and enhancers of Ca2+ signaling. Two of the inhibitors could be shown to interfere with Ca2+ signaling by specifically targeting parasite PKG. In contrast, the enhancers could be shown to increase Ca2+ independently from zaprinast and in fact prevented parasite egress by apparently depleting intracellular Ca2+ stores. This compound displayed antiparasitic properties against both T. gondii and P. falciparum, establishing a new mechanism for interfering with apicomplexan parasitism.

The signaling events that trigger parasite egress remain poorly defined. Ca2+ ionophores have long been known to stimulate egress in T. gondii (64). However, more recently, phosphodiesterase inhibitors were shown to have similar effects (20, 61). Our experiments revealed a strong and rapid release of Ca2+ in response to zaprinast treatment through the use of both the established Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 and the newly adapted genetically encoded sensors GCaMP5 and GCaMP6f (29). We provide conclusive evidence linking PKG to the zaprinast-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+, using a chemical-genetic approach to demonstrate specific inhibition of PKG by Cpd1 and Cpd2. Sensitivity to both inhibitors depends on the relatively small gatekeeper of apicomplexan PKGs, which we mutated to a methionine that preserves kinase activity but renders PKG refractory to inhibition (31). The changes in the zaprinast response caused by Cpd1 can therefore be fully attributed to PKG because no such changes were observed upon treatment of the resistant strain (PKG-M). However, comparing the response to zaprinast in parasites pretreated with Cpd1 with those pretreated with vehicle shows that the initial sharp Ca2+ peak induced by zaprinast is incompletely suppressed by Cpd1, in contrast to its complete inhibition of zaprinast-induced egress (20). Suppression of this peak appeared greater when assayed using Fura-2 (Fig. 1D) than when using GCaMP6 (Fig. 4B). This may result from the semiquantitative nature of GCaMP6 and the potentially non-linear relationship between fluorescence and Ca2+ concentration. Additionally, differences in the subcellular distribution of the two indicators may influence their responses to different sources of Ca2+. Ratiometric measurements with Fura-2 also revealed that inhibition of PKG by Cpd1 decreased basal Ca2+ concentrations in extracellular parasites, suggesting that PKG might also be necessary to maintain resting levels of Ca2+ in extracellular parasites. These changes in basal Ca2+ concentrations might not be evident with GCaMP6f due to its higher Kd (375 nm) (59) compared with that of Fura-2 (135 nm) (43).

We characterized the zaprinast-mobilized store as neutral because it can be depleted by ionomycin. However, we found that this store is independent of the thapsigargin-mobilizable store. This is surprising, given that the ER is the only neutral Ca2+ store that has been characterized in T. gondii. SERCA, the target of thapsigargin, localizes to the ER in intracellular parasites but redistributes so as to only partially colocalize with the ER in extracellular parasites (54). Because our experiments were done in extracellular parasites, it is possible that zaprinast mobilizes Ca2+ from a section of the ER lacking SERCA under these conditions, as previously suggested for the ethanol-mobilized Ca2+ stores (65). In P. falciparum, zaprinast has been shown to work through P. falciparum PKG to trigger changes in the levels of various precursors of the second messenger IP3. Presumably, this increases IP3, which then interacts with the IP3 receptor to stimulate release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (19). An IP3 receptor has not been identified in apicomplexans, but treating parasites with ethanol raises levels of IP3 and stimulates Ca2+ release, providing evidence for the presence of such a channel (66). Our results therefore indicate that zaprinast functions, at least in part, through T. gondii PKG and probably mobilizes a neutral, SERCA-independent, IP3 receptor-gated store.

Genetically encoded calcium indicators provide excellent reproducibility and circumvent many problems associated with loading and compartmentalization of chemical probes. Here we demonstrate that such indicators can be used to identify compounds that alter apicomplexan Ca2+ signaling and its dependent processes, such as egress and invasion. The simplicity and robustness of this cell-based phenotypic screen, with a Z′-factor >0.5, makes it compatible with high throughput screening efforts. As proof of concept, we screened a library of 823 ATP mimetics from GlaxoSmithKline for compounds that could alter the zaprinast-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+. Identification of two PKG inhibitors, with distinct chemical scaffolds and mechanisms of inhibition, validated our screen and demonstrates the power of the approach. Unexpectedly, our screen also revealed two compounds that, when used in combination with zaprinast, augmented Ca2+ levels. One such compound, Enh1, elicited repeated cycles of Ca2+ increase and decrease with overall cytosolic Ca2+ building at a population level. These repeated cycles are reminiscent of what others have seen when Fluo-4/AM-loaded parasites were treated with thapsigargin (54), perhaps indicating that Enh1 also inhibits Ca2+ uptake pathways.

In contrast to zaprinast and Ca2+ ionophores, Enh1 failed to stimulate egress despite raising cytosolic Ca2+ levels. In fact, Enh1 blocked the ability of these agonists to stimulate parasite egress. Furthermore, treatment with Enh1 blocked tachyzoite invasion and plaque formation at concentrations similar to those required to block egress. These results suggest that Enh1 depletes essential intracellular Ca2+ stores, which have been previously suggested to mediate invasion and egress. Consistent with this view, we observed diminished changes in GCaMP fluorescence in response to zaprinast, following Enh1 treatment (Fig. 6C). However, without a complete understanding of Enh1 function, we cannot rule out the possibility that inhibition of egress may be independent of its ability to modulate Ca2+ because (i) some parasites in which Enh1 did not elicit Ca2+ fluctuations still failed to egress in response to zaprinast, and (ii) A23187, which should equilibrate Ca2+ across membranes, failed to overcome Enh1 inhibition. Compounds similar to Enh1 have been shown to inhibit mammalian kinases belonging to the AGC family (67). Having already established that T. gondii PKG, a member of the AGC kinase family, mediates Ca2+ release, it is an intriguing possibility that a related kinase might oppose its activity.

Enh1 robustly inhibited the ability of P. falciparum to invade erythrocytes, although it did not affect egress. Despite the many parallels between egress of P. falciparum and T. gondii, substantial differences have also been uncovered. Plasmodium egress is a fast, highly synchronized process, dependent on a cascade of proteolytic activity (68). Genetic evidence supports this distinction with mutants in the calcium-responsive protein DOC2.1 blocking both egress and invasion in T. gondii but only invasion in P. falciparum (69), mirroring the effects of Enh1. The intracellular Ca2+ stores of Plasmodium have not been investigated as thoroughly as those of T. gondii, but there is some evidence that it is not solely dependent on its intracellular Ca2+ stores and in fact utilizes Ca2+ found within the parasitophorous vacuole (70). In light of this, the differential responses of P. falciparum and T. gondii to Enh1 are perhaps not surprising. That Enh1 blocks invasion of P. falciparum demonstrates this compound's ability to perturb Ca2+-dependent processes across multiple members of the Apicomplexa.

Resistance to front line antimalarials is increasing (71, 72), and new treatment options are needed. Rational design strategies can identify drugs with minimal off-target effects but focus on a limited repertoire of signaling pathways. The Toxoplasma Ca2+ signaling network shows evidence of conservation within apicomplexans while being dissimilar to human signaling pathways. By screening for modulation of this pathway, we have prioritized compounds that are likely to interfere selectively with infection without focusing on a single parasite protein. This screen can be performed with commonly available equipment and should be easily scalable to larger collections of compounds. Our success in identifying new modulators of Ca2+ signaling with effects that extend to multiple apicomplexans highlights the power of such an approach. In particular, Enh1 inhibits parasite viability with an EC50 in the nanomolar range and provides a good lead for the development of antiparasitic compounds. Further characterization of these compounds may identify novel components of apicomplexan Ca2+ signaling pathways and improve our ability to target these pathways specifically.

Author Contributions

S. M. S., M. A. H. T., and A. S. P. designed and conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. S. M. S. wrote the majority of the manuscript, with specific sections contributed by M. A. H. T. and A. S. P. C. G. H. constructed the T. gondii strains with different PKG alleles. M. E. B., R. H., and W. J. Z. provided key reagents and advice. F. T. and N. J. W. synthesized Cpd2. M. T. D., S. N. J. M., and S. L. supervised the work in their respective laboratories and contributed to the analysis of experiments and writing of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Drewry for helpful advice regarding the compound libraries, Jeroen P. J. Saeij for providing the GFP-expressing strain, and Emily M. Shortt for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AI-110027 and AI-096836 (to S. N. J. M.) and 1DP5OD017892 (to S. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Table S1, Figs. S1 and S2, and Videos S1–S3.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GPN

- l-phenylalanine-naphthylamide

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- PKG

- protein kinase G

- HFF

- human foreskin fibroblast

- PP

- pyrazolopyridazine

- Cpd1 and Cpd2

- compound 1 and 2, respectively

- Enh1 and Enh2

- enhancer 1 and 2, respectively

- Inh1 and Inh2

- inhibitor 1 and 2, respectively.

References

- 1. Carruthers V. B., and Sibley L. D. (1999) Mobilization of intracellular calcium stimulates microneme discharge in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wetzel D. M., Chen L. A., Ruiz F. A., Moreno S. N. J., and Sibley L. D. (2004) Calcium-mediated protein secretion potentiates motility in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5739–5748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Billker O., Lourido S., and Sibley L. D. (2009) Calcium-dependent signaling and kinases in apicomplexan parasites. Cell Host Microbe 5, 612–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arrizabalaga G., and Boothroyd J. C. (2004) Role of calcium during Toxoplasma gondii invasion and egress. Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCallum-Deighton N., and Holder A. A. (1992) The role of calcium in the invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 50, 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Singh S., Alam M. M., Pal-Bhowmick I., Brzostowski J. A., and Chitnis C. E. (2010) Distinct external signals trigger sequential release of apical organelles during erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lovett J. L., and Sibley L. D. (2003) Intracellular calcium stores in Toxoplasma gondii govern invasion of host cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3009–3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moudy R., Manning T. J., and Beckers C. J. (2001) The loss of cytoplasmic potassium upon host cell breakdown triggers egress of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41492–41501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pace D. A., McKnight C. A., Liu J., Jimenez V., and Moreno S. N. J. (2014) Calcium entry in Toxoplasma gondii and its enhancing effect of invasion-linked traits. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19637–19647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. English A. R., and Voeltz G. K. (2013) Endoplasmic reticulum structure and interconnections with other organelles. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a013227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Golovina V. A., and Blaustein M. P. (1997) Spatially and functionally distinct Ca2+ stores in sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum. Science 275, 1643–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calcraft P. J., Ruas M., Pan Z., Cheng X., Arredouani A., Hao X., Tang J., Rietdorf K., Teboul L., Chuang K.-T., Lin P., Xiao R., Wang C., Zhu Y., Lin Y., et al. (2009) NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature 459, 596–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pinton P., Pozzan T., and Rizzuto R. (1998) The Golgi apparatus is an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ store, with functional properties distinct from those of the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 17, 5298–5308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koch G. L. E. (1990) The endoplasmic reticulum and calcium storage. Bioessays 12, 527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stelly N., Mauger J. P., Claret M., and Adoutte A. (1991) Cortical alveoli of Paramecium: a vast submembranous calcium storage compartment. J. Cell Biol. 113, 103–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Plattner H., Habermann A., Kissmehl R., Klauke N., Majoul I., and Söling H. D. (1997) Differential distribution of calcium stores in Paramecium cells: occurrence of a subplasmalemmal store with a calsequestrin-like protein. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 72, 297–306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moreno S. N., and Zhong L. (1996) Acidocalcisomes in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Biochem. J. 313, 655–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miranda K., Pace D. A., Cintron R., Rodrigues J. C. F., Fang J., Smith A., Rohloff P., Coelho E., de Haas F., de Souza W., Coppens I., Sibley L. D., and Moreno S. N. J. (2010) Characterization of a novel organelle in Toxoplasma gondii with similar composition and function to the plant vacuole. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1358–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brochet M., Collins M. O., Smith T. K., Thompson E., Sebastian S., Volkmann K., Schwach F., Chappell L., Gomes A. R., Berriman M., Rayner J. C., Baker D. A., Choudhary J., and Billker O. (2014) Phosphoinositide metabolism links cGMP-dependent protein kinase G to essential Ca2+ signals at key decision points in the life cycle of malaria parasites. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lourido S., Tang K., and Sibley L. D. (2012) Distinct signalling pathways control Toxoplasma egress and host-cell invasion. EMBO J. 31, 4524–4534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuasa K., Mi-Ichi F., Kobayashi T., Yamanouchi M., Kotera J., Kita K., and Omori K. (2005) PfPDE1, a novel cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase from the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 392, 221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Collins C. R., Hackett F., Strath M., Penzo M., Withers-Martinez C., Baker D. A., and Blackman M. J. (2013) Malaria parasite cGMP-dependent protein kinase regulates blood stage merozoite secretory organelle discharge and egress. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lourido S., Zhang C., Lopez M. S., Tang K., Barks J., Wang Q., Wildman S. A., Shokat K. M., and Sibley L. D. (2013) Optimizing small molecule inhibitors of calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 to prevent infection by Toxoplasma gondii. J. Med. Chem. 56, 3068–3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson S. M., Murphy R. C., Geiger J. A., DeRocher A. E., Zhang Z., Ojo K. K., Larson E. T., Perera B. G. K., Dale E. J., He P., Reid M. C., Fox A. M. W., Mueller N. R., Merritt E. A., Fan E., et al. (2012) Development of Toxoplasma gondii calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (TgCDPK1) inhibitors with potent anti-toxoplasma activity. J. Med. Chem. 55, 2416–2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wiersma H. I., Galuska S. E., Tomley F. M., Sibley L. D., Liberator P. A., and Donald R. G. K. (2004) A role for coccidian cGMP-dependent protein kinase in motility and invasion. Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taylor H. M., McRobert L., Grainger M., Sicard A., Dluzewski A. R., Hopp C. S., Holder A. A., and Baker D. A. (2010) The malaria parasite cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase plays a central role in blood-stage schizogony. Eukaryot. Cell 9, 37–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gurnett A. M., Liberator P. A., Dulski P. M., Salowe S. P., Donald R. G. K., Anderson J. W., Wiltsie J., Diaz C. A., Harris G., Chang B., Darkin-Rattray S. J., Nare B., Crumley T., Blum P. S., Misura A. S., et al. (2002) Purification and molecular characterization of cGMP-dependent protein kinase from Apicomplexan parasites: a novel chemotherapeutic target. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15913–15922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lim D. C., Cooke B. M., Doerig C., and Saeij J. P. J. (2012) Toxoplasma and Plasmodium protein kinases: roles in invasion and host cell remodelling. Int. J. Parasitol. 42, 21–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borges-Pereira L., Budu A., McKnight C. A., Moore C. A., Vella S. A., Hortua Triana M. A., Liu J., Garcia C. R. S., Pace D. A., and Moreno S. N. J. (2015) Calcium signaling throughout the Toxoplasma gondii lytic cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 26914–26926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng W., Thorne N., and McKew J. C. (2013) Phenotypic screens as a renewed approach for drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 18, 1067–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sidik S. M., Hackett C. G., Tran F., Westwood N. J., and Lourido S. (2014) Efficient genome engineering of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS One 9, e100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akerboom J., Chen T.-W., Wardill T. J., Tian L., Marvin J. S., Mutlu S., Calderón N. C., Esposti F., Borghuis B. G., Sun X. R., Gordus A., Orger M. B., Portugues R., Engert F., Macklin J. J., et al. (2012) Optimization of a GCaMP calcium indicator for neural activity imaging. J. Neurosci. 32, 13819–13840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soldati D., and Boothroyd J. C. (1995) A selector of transcription initiation in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 87–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boyle J. P., Saeij J. P. J., and Boothroyd J. C. (2007) Toxoplasma gondii: inconsistent dissemination patterns following oral infection in mice. Exp. Parasitol. 116, 302–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., and Bourne P. E. (2000) The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stevens K. L., Reno M. J., Alberti J. B., Price D. J., Kane-Carson L. S., Knick V. B., Shewchuk L. M., Hassell A. M., Veal J. M., Davis S. T., Griffin R. J., and Peel M. R. (2008) Synthesis and evaluation of pyrazolo[1,5-b]pyridazines as selective cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 5758–5762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Simard J. R., Getlik M., Grütter C., Pawar V., Wulfert S., Rabiller M., and Rauh D. (2009) Development of a fluorescent-tagged kinase assay system for the detection and characterization of allosteric kinase inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13286–13296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kinoshita T., Warizaya M., Ohori M., Sato K., Neya M., and Fujii T. (2006) Crystal structure of human ERK2 complexed with a pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridazine derivative. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 55–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Islam I., Bryant J., Chou Y.-L., Kochanny M. J., Lee W., Phillips G. B., Yu H., Adler M., Whitlow M., Ho E., Lentz D., Polokoff M. A., Subramanyam B., Wu J. M., Zhu D., et al. (2007) Indolinone based phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) inhibitors. Part 1: design, synthesis and biological activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17, 3814–3818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rellos P., Ivins F. J., Baxter J. E., Pike A., Nott T. J., Parkinson D.-M., Das S., Howell S., Fedorov O., Shen Q. Y., Fry A. M., Knapp S., and Smerdon S. J. (2007) Structure and regulation of the human Nek2 centrosomal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6833–6842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., Tinevez J.-Y., White D. J., Hartenstein V., Eliceiri K., Tomancak P., et al. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]