Summary

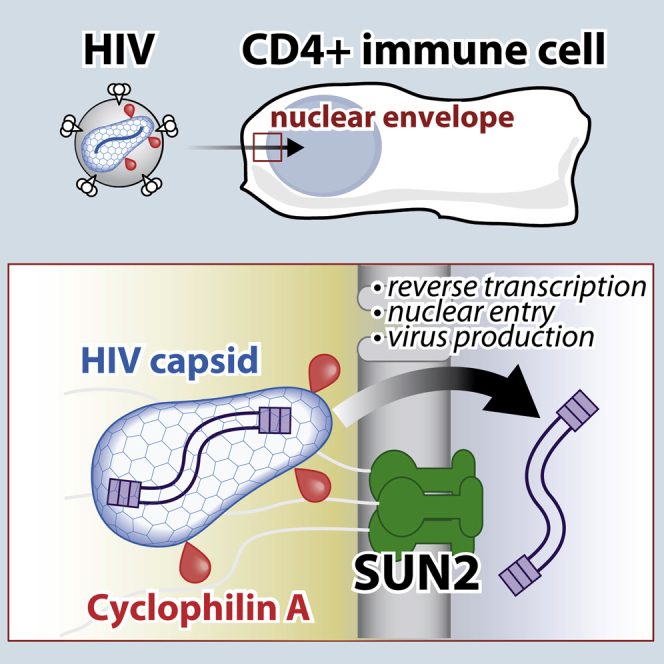

During the early phase of replication, HIV reverse transcribes its RNA and crosses the nuclear envelope while escaping host antiviral defenses. The host factor Cyclophilin A (CypA) is essential for these steps and binds the HIV capsid; however, the mechanism underlying this effect remains elusive. Here, we identify related capsid mutants in HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIVmac that are restricted by CypA. This antiviral restriction of mutated viruses is conserved across species and prevents nuclear import of the viral cDNA. Importantly, the inner nuclear envelope protein SUN2 is required for the antiviral activity of CypA. We show that wild-type HIV exploits SUN2 in primary CD4+ T cells as an essential host factor that is required for the positive effects of CypA on reverse transcription and infection. Altogether, these results establish essential CypA-dependent functions of SUN2 in HIV infection at the nuclear envelope.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

HIV capsid mutants reveal that Cyclophilin A can restrict viral nuclear import

-

•

Nuclear envelope protein SUN2 is implicated in the restriction of HIV mutants

-

•

SUN2 is essential for wild-type HIV infection in CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells

-

•

In CD4+ T cells, the activities of CypA on HIV-1 infection require SUN2

Host protein Cyclophilin A helps HIV-1 infection through a poorly resolved mechanism. Lahaye et al. identify that the nuclear envelope protein SUN2 is required for the activities of Cyclophilin A during infection and that SUN2 is essential for HIV-1 replication in primary CD4+ cells, pointing to weaknesses in the virus.

Introduction

HIV replication requires the successful orchestration of reverse transcription, nuclear entry, and integration while avoiding various antiviral factors and innate immune sensors during early steps of infection (Malim and Bieniasz, 2012). Recognition of HIV by innate immune sensors induces the production of type I interferons and consequently interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), some of which possess direct antiviral activity against HIV replication (Schoggins et al., 2011). Along with ISGs, cells are also equipped with intrinsic antiviral factors, including restriction factors that constitutively protect the cell from infection (Bieniasz, 2004). Cyclophilin A (CypA), a host peptidylprolyl isomerase, was the first host factor shown to bind the HIV-1 capsid protein and to be required for the early steps of infection (Luban et al., 1993). Since the capsid core efficiently protects the genome of pathogenic HIV-1, engages essential host-derived replication factors, and enables evasion of antiviral factors and innate immune sensors, its interaction with CypA is of particular interest (Campbell and Hope, 2015). To date, CypA has not been associated with specific cellular pathways in human cells, and the nature of cellular factor(s) required for the effects of CypA on HIV-1 infection has remained elusive (Hilditch and Towers, 2014).

In primary CD4+ target cells, HIV depends on CypA for maximal replication (De Iaco and Luban, 2014, Franke et al., 1994, Saini and Potash, 2006, Schaller et al., 2011, Yoo et al., 1997). Use of the CypA inhibitor Cyclosporin A (CsA) demonstrated that optimal reverse transcription of HIV-1 (Braaten et al., 1996) and viral nuclear import (De Iaco and Luban, 2014) requires CypA in many cell lines, consistent with the ability of lentiviruses to infect non-dividing cells and with the presence of a conserved CypA-binding loop in their capsid (Goldstone et al., 2010, Lin and Emerman, 2006, Yamashita and Emerman, 2004). CypA also influences HIV-1 integration sites (Schaller et al., 2011) and the evasion of cytosolic innate sensors in monocyte-derived macrophages (Rasaiyaah et al., 2013). Unlike HIV-1, HIV-2 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)mac replication is modestly affected by inhibition of CypA in cell lines (Billich et al., 1995, Thali et al., 1994). Accordingly, HIV-1 capsid binds CypA with an affinity in the micromolar range, while HIV-2 and the related SIVmac capsids bind CypA with a much lower affinity (Price et al., 2009, Schaller et al., 2011). In several cell lines such as HeLa, HIV-1 does not depend on CypA (Sokolskaja et al., 2004, Thali et al., 1994), and heterokaryon experiments suggest instead that CypA controls a dominant restriction mechanism specific to HeLa cells and to capsid mutants A92E and G94D (Song and Aiken, 2007). Mutations conferring a restriction phenotype that would be both associated with CypA and conserved across cell types in single-cycle virus infection assays have remained elusive.

Additional host factors that regulate the early steps of HIV-1 replication are also associated with capsid. For instance, CPSF6, RANBP2 (NUP358), NUP153, and Rhesus TRIM5α all bind to the viral capsid (Di Nunzio et al., 2012, Ganser-Pornillos et al., 2011, Lee et al., 2010, Matreyek and Engelman, 2011, Meehan et al., 2014, Price et al., 2012, Schaller et al., 2011, Stremlau et al., 2004). TNPO3 is also required for HIV-1 infection and this requirement maps genetically in part to the viral capsid (Brass et al., 2008, Krishnan et al., 2010). Interestingly, the resistance factor MX2 inhibits HIV-1 infection after reverse transcription, and this maps to the interaction between the viral capsid and CypA (Goujon et al., 2013, Kane et al., 2013, Liu et al., 2013). The understanding of the orchestration of the early steps of HIV-1 infection by these factors, particularly at the step of nuclear entry of the viral pre-integration complex, remains incomplete (Gaudin et al., 2013). Mutations in the viral capsid that alter CypA binding also modulate the effects of these factors on infection, leading to the notion that CypA binding to capsid influences interactions (genetic or biochemical) with these factors (Sokolskaja and Luban, 2006). However, no essential host factor is known to be required for the effects of CypA on HIV-1 infection.

CypA binds to a characteristic proline-containing loop that is present in lentiviruses but absent from other retroviruses (Goldstone et al., 2010, Lin and Emerman, 2006) and affects the isomerization of proline 90 in HIV-1 capsid (Bosco et al., 2002). We previously described chimeric mutants of HIV-1 and HIV-2, corresponding to naturally occurring amino acids, with an increased affinity for CypA: P86HA in HIV-2 (short HIVac-2; HIV CypA affinity-enhanced capsid) and V86I-IAP91LPA-M96L in HIV-1 (short HIVac-1) (Lahaye et al., 2013). In monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDCs), a physiologically relevant CD4+ target cell derived from primary blood monocytes, HIVac-1 and HIVac-2 promote innate sensing of the viral cDNA by the cytosolic DNA sensor cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) before nuclear import (Lahaye et al., 2013). This response requires abrogation of SAMHD1 using Vpx present in HIV-2/SIVmac (Hrecka et al., 2011, Laguette et al., 2011, Manel et al., 2010). In addition, these mutants show a striking defect in infection of MDDCs, downstream of the SAMHD1 restriction (Lahaye et al., 2013). Neutralizing type I interferon (IFN) does not rescue infection by HIVac-2, suggesting that the inhibition is not secondary to the induction of an antiviral innate immune state. HIVac-2 gives rise to normal levels of late reverse transcription (late RT) products, but reduced levels of 2-LTR circles and integrated viral DNA, as compared to HIV-2, suggesting a restriction before nuclear import. We surmised that the increased affinity of HIVac-2 for CypA rendered the virus intrinsically susceptible to antiviral restriction mediated by CypA at the level of nuclear import. Normally, wild-type (WT) HIV would avoid such CypA-mediated resistance, a typical characteristic of restriction factors (Malim and Bieniasz, 2012). This observation raised the possibility that the underlying restriction mechanism could shed light on the long-sought host factors implicated in the positive effects of CypA in HIV-1 infection.

Results

CypA Is Required for Restriction of HIVac Capsid

MDDCs were susceptible to infection by HIV-1 with Vpx, but not to HIVac-2 infection (Figure S1A). We examined whether the resistance to HIVac-2 infection was intrinsic to the virus. Upon combined infection with the two viruses, when HIVac-2 was present and activated an innate immune response in MDDCs as shown by CD86 induction, cells remained susceptible to HIV-1 with Vpx (Figure S1A). Thus, the resistance to HIVac-2 infection is unlikely due to the induction of an antiviral state but appears to be intrinsically linked to the capsid.

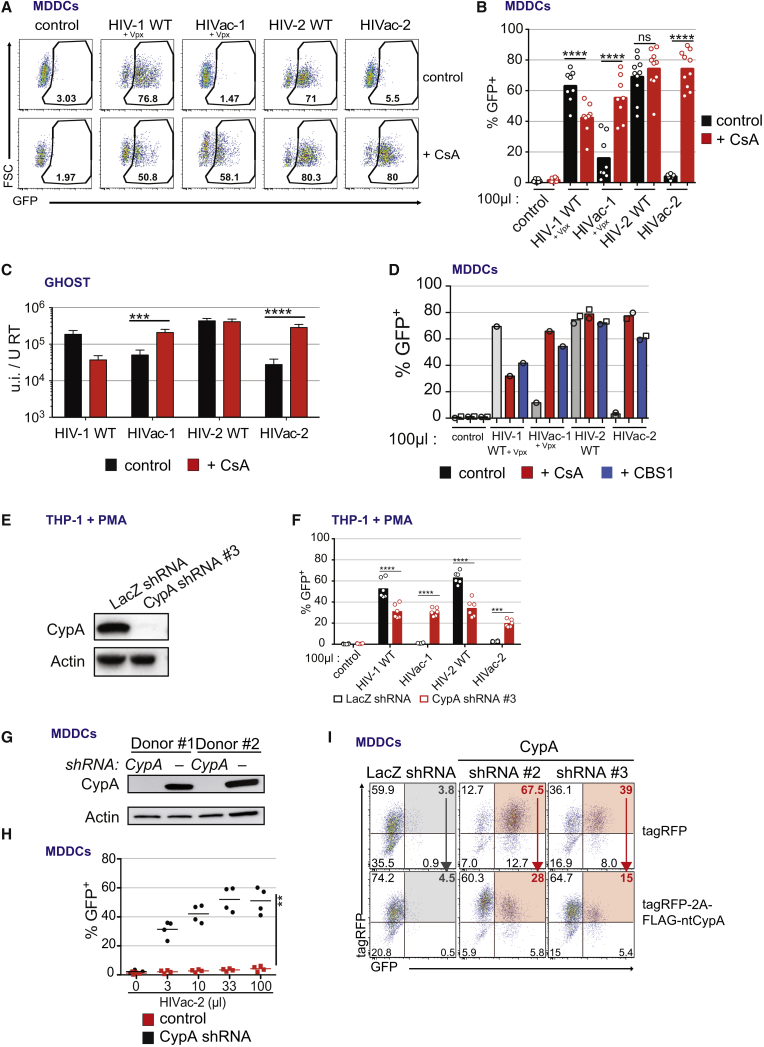

In order to examine the role of CypA in HIV resistance, we treated MDDCs with CsA at the time of infection. CsA modestly increased HIV-2 infectivity and decreased HIV-1 infectivity, consistent with previous reports (Manel et al., 2010, Virgen et al., 2008) (Figures 1A, 1B, S1B, and S1C). Strikingly, in the case of infection of DCs with HIVac-1 and HIVac-2, the presence of CsA restored infectivity (Figures 1A, 1B, S1B, and S1C). This indicated that the HIVac mutations enabled a CypA-mediated restriction of infection.

Figure 1.

CypA Is Required for a Restriction of HIV-1 and HIV-2 Capsid Mutants

(A) GFP expression in MDDCs 48 hr after infection with HIV-1 WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, and HIVac-2 encoding GFP in Nef and pseudotyped with VSV-G in the presence SIVmac251 VLPs (Vpx) and treated or not with CsA (2 μM) (n = 5; representative data for one donor are shown).

(B) GFP expression in MDDCs (n = 10 except HIV-1 viruses n = 8, paired t test, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant; bar indicates mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(C) Infectious titer of HIV-1 WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, and HIVac-2 on GHOST cells normalized to reverse transcriptase titer of the inoculum, in the presence or absence of CsA (2 μM) (n = 12, paired t test on log-transformed data, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean ± SEM).

(D) GFP expression in MDDCs 48 hr after infection with HIV-1 WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, and HIVac-2 in the presence SIVmac251 VLPs (Vpx) and treated or not with 2 μM of CBS1 or CsA (n = 2, except HIV-1 viruses n = 1; open symbols, individual donors; bar, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(E) Western blot analysis of CypA and actin expression in THP-1 cells transduced with a control shRNA against LacZ or shRNA #3 against of CypA.

(F) GFP expression in PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells transduced with a control shRNA against LacZ or shRNA #3 against of CypA, 48 hr after infection with HIV-1WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, and HIVac-2 (n = 6, paired t test, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, bar indicates mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(G) Western blot analysis of CypA and actin expression (day 4). MDDCs were transduced at day 0 with three shRNA vectors against CypA or a shRNA control vector.

(H) MDDCs as in (G) were infected at day 4 with HIVac-2. Proportion of GFP-positive cells after 48 hr of infection (n = 4, paired t test, ∗∗p < 0.01, line indicates mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(I) MDDCs were transduced at day 0 with a single shRNA vector against CypA or control vector, together with a tagRFP-encoding vector or a tagRFP-2A-FLAG-ntCypA-encoding vector, and infected at day 4 with HIVac-2 (n = 5). GFP and tagRFP expression in a representative donor is shown. Red arrows indicate the rescue of the restriction by the expression of the ntCypA in absence of the endogenous CypA.

See also Figure S1.

Next, we reasoned that, if the restriction of HIVac viruses was not a consequence of the induction of an antiviral state in immune cells, then it must be conserved. HIVac-1 and HIVac-2 titers were decreased compared to their WT counterparts following infection of immune-related THP-1 cells and non-immune GHOST cells (Figures 1C, S1D, and S1E). CsA restored infection of HIVac-1 and HIVac-2 to levels comparable with those of the WT viruses. CsA, an immunosuppressive compound, also targets proteins other than CypA. To confirm the role of CypA, we used a non-immunosuppressive CypA inhibitor, CBS1. CBS1 also rescued infectivity of HIVac-1 and HIVac-2 (Figure 1D). Knockdown of CypA expression in MDDCs and THP-1 using short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-coding lentivectors also restored infectivity of HIVac-2 (Figures 1E–1H). Expression of a non-targetable CypA protein together with the shRNA reverted the inhibition of HIVac-2 infection (Figures 1I and S1F–S1I). To genetically confirm the role of CypA, we used PPIA−/− Jurkat cells that are genetically defective for CypA expression (Braaten and Luban, 2001). As was the case for MDDCs and GHOST cells, infection of WT Jurkat cells by HIVac-2 was inhibited, and addition of CsA rescued infectivity (Figures S1J and S1K). In contrast, infectivity of HIVac-2 was similar to HIV-2 in PPIA−/− Jurkat cells, and CsA had no further effect on infectivity. Thus, CypA is essential to restrict HIVac-1 and HIVac-2 capsid mutants.

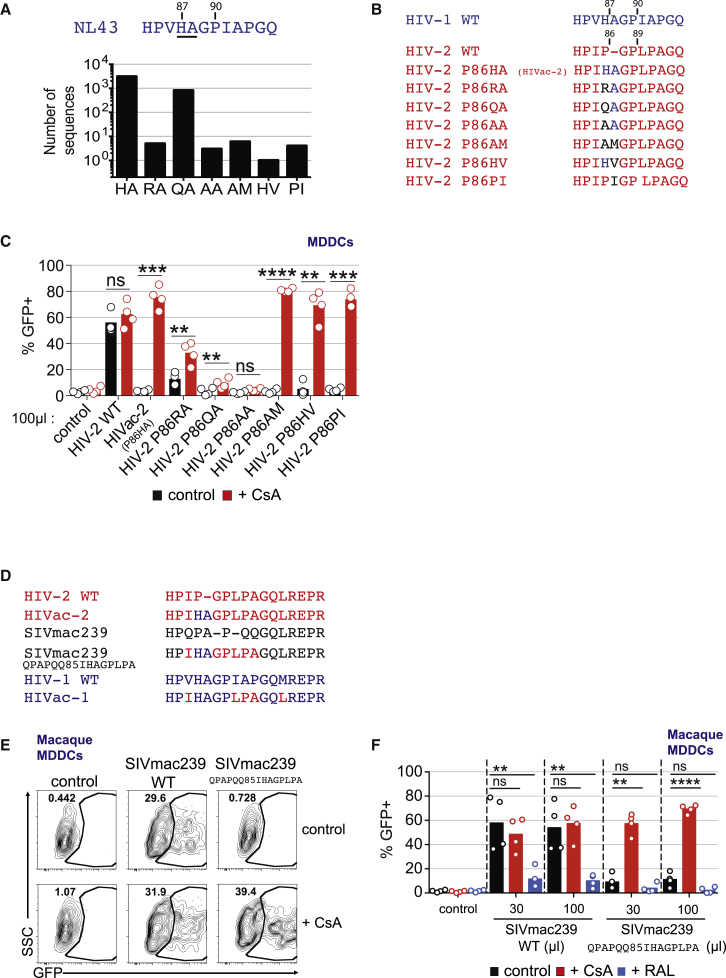

CypA Mediates a Conserved Restriction of a Family of Lentiviral Capsid Mutants

Next, we examined whether the CypA restriction was limited to a specific HIVac capsid sequence or whether it could be extended to a general family of lentiviral capsid mutants. The distinctive feature of HIVac-2 is the rational exchange of Proline 86 with a corresponding pair of naturally occurring amino acids Histidine-Alanine in HIV-1 NL4-3, in order to restore a CypA-binding loop that would presumably fit the catalytic site of CypA more closely (Lahaye et al., 2013). We examined an alignment of 4,132 sequences of HIV-1 capsid available at the time in the Los Alamos National Laboratory database and extracted all the existing pairs of amino acids preceding Glycine 89-Proline 90. We identified six additional amino acid pairs and introduced them into HIV-2 ROD9 (Figures 2A and 2B). In accordance with HIVac-2, these six mutants encapsidated higher amounts of CypA protein in the viral particles (between 20- and 50-fold more, Figure S2A), consistent with an increased affinity of these mutated capsids for CypA (Lahaye et al., 2013). On GHOST cells and MDDCs, infectivity was consistently low and rescued by CsA, except for one mutant P86AA (Figures 2C and S2B). HIV-2 is closely related to SIVmac, but their CypA-binding loops differ. To examine whether the CypA restriction was applicable to primate lentiviruses other than HIV, we generated a mutant of SIVmac239 encoding for the CypA-binding loop of HIVac-2, resulting in virus SIVmac239 QPAPQQ85IHAGPLPA (Figure 2D). We also generated macaque monocyte-derived dendritic cells (O’Doherty et al., 1997) (Figure S2C). Macaque MDDCs were readily infected with VSV-G pseudotyped GFP-encoding SIVmac239 (Figures 2E and 2F). Infection was inhibited by Raltegravir, confirming that GFP was expressed from integrated virus. CsA did not alter SIVmac239 infection. In contrast, infectivity of SIVmac239 QPAPQQ85IHAGPLPA was inhibited in macaque MDDCs, and CsA treatment restored GFP expression. Thus, CypA restriction of lentiviral infection is conserved in macaque cells and affects a broad family of capsid mutants.

Figure 2.

CypA Induces a Direct Antiviral Resistance against a Family of Capsid Mutants in HIV and SIV that Is Conserved in Human and Macaque Cells

(A) 4,132 sequences of HIV-1 capsid available in the Los Alamos National Laboratory database were aligned and six unique pairs of amino acids preceding Glycine 89-Proline 90 were extracted. A histogram of the number of sequences for this pair of amino acids at this position is shown.

(B) Alignment of the CypA-binding loops of HIV-1 WT, HIV-2 WT, HIVac-2 capsids, and the six pairs of amino acids (as in Figure 4A) in HIV-2 ROD9 instead of Proline 86.

(C) GFP expression in MDDCs 48 hr after infection with HIV-2 WT, HIVac-2, and additional HIV-2 mutants (as indicated) in the presence or absence of CsA (2 μM) (n = 4, paired t test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(D) Alignment of the CypA-binding loops of HIV-1 WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, HIVac-2, SIVmac239, and SIVmac239 QPAPQQ85IHAGPLPA.

(E) GFP expression in macaque MDDCs 48 hr after infection with SIVmac239 and SIVmac239 QPAPQQ85IHAGPLPA encoding GFP in Nef and pseudotyped with VSV-G and treated or not with CsA (2 μM) or raltegravir (RAL) (20 μM) (n = 4; representative data for one donor are shown).

(F) GFP expression as in Figure 2E (n = 4, paired t test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

See also Figure S2.

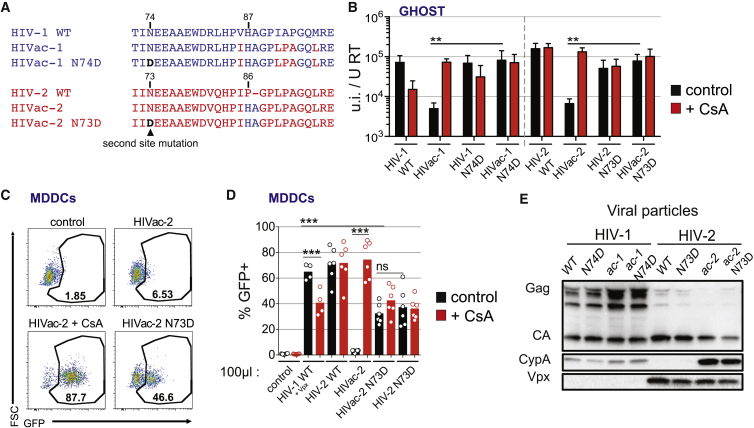

Second-Site Mutations in HIVac Capsid Rescue the CypA Restriction

To determine whether CypA was sufficient for restriction, we explored the phenotype of second-site mutations in the capsid mutants. The capsid mutant HIV-1 N74D, but not HIV-1 WT, has been previously shown to be sensitive to CsA in HeLa cells (Ambrose et al., 2012, Yang and Aiken, 2007). This suggested that N74 might influence the restriction mediated by CypA on HIVac-1 and HIVac-2. Strikingly, the infectivity of HIVac-1 N74D and HIVac-2 N73D was largely restored and was insensitive to CsA in HeLa cells, GHOST cells, and MDDCs (Figures 3A–3D, S3A, and S3B). Importantly, the second-site mutation did not abrogate the increase in CypA recruitment to the HIVac-2 N73D capsid (Figures 3E and S3C). Thus, N74D/N73D constitute second-site mutations in capsids that specifically escape the direct antiviral effect of CypA, suggesting that additional host factors are implicated in the restriction.

Figure 3.

Second-Site Mutations in HIVac Capsid Rescue the CypA Restriction

(A) Alignment of the capsids of HIV-1 WT, HIVac-1, HIVac-1 N74D, HIV-2 WT, HIVac-2, and HIVac-2 N73D. The CypA-binding loop and its N-terminally adjacent domain are shown.

(B) Infectious titer of indicated viruses on GHOST cells normalized to reverse transcriptase titer of the inoculum, in the presence or absence of CsA (2 μM) (n = 4 for HIV-1 viruses and n = 3 for HIV-2 viruses, paired t test on log-transformed data, ∗∗p < 0.01; bar, mean ± SEM).

(C) GFP expression in MDDCs 48 hr after infection with HIVac-2 and HIVac-2 N73D viruses treated or not with CsA (2 μM) (n = 6, representative data for one donor are shown).

(D) Quantification of GFP expression as in (C) (n = 6 except HIV-1 viruses n = 4, paired t test, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(E) Western blot analysis of Gag/Ca, CypA in Vpx in viral particles as indicated.

See also Figure S3.

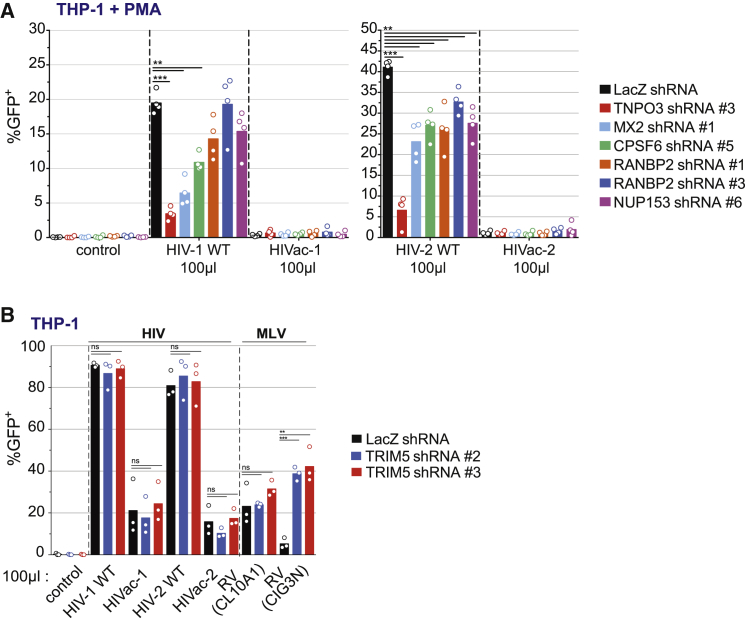

Role of Known Capsid-Associated Factors in the Restriction

Next, we examined whether host factors that bind the lentiviral capsid or whose activity genetically maps to the capsid would be necessary for the restriction. We focused on THP-1 cells, because GHOST cells are already multi-resistant to antibiotic selection, and sufficient knockdown was difficult to achieve for several host factors in MDDCs (data not shown). We knocked down MX2, TNPO3, CPSF6, NUP153, RANBP2, and TRIM5 and tested whether this would rescue infection by HIVac-1 or HIVac-2. Knockdowns were confirmed by western blot for MX2, CPSF6, and TNPO3 (Figure S4A), and by qPCR for RANBP2, NUP153, and TRIM5 (Figure S4B). Depletion of TNPO3, CPSF6, NUP153, RANBP2, and MX2 reduced HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections, with TNPO3 depletion having the strongest inhibitory effect (Figures 4A and S4C). Depletion of TRIM5 did not affect HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection but rescued infection by a N-MLV retroviral vector (Bock et al., 2000) (Figures 4B and S4D). These effects validated the functional impact of all knockdowns on HIV infection in THP-1 cells. However, there was no rescue of HIVac-1 or HIVac-2 infection in any of these cases.

Figure 4.

Role of Known Capsid-Associated Factors in the Restriction

(A) GFP expression in PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells transduced with a control shRNA against LacZ or individual shRNA against TNPO3, CPSF6, NUP153, RANBP2, MX2, 48 hr after infection with HIV-1WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, and HIVac-2 (n = 4, paired t test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, bar indicates mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(B) GFP expression in THP-1 cells transduced with a control shRNA against LacZ or two individual shRNA against TRIM5, 48 hr after infection with HIV-1WT, HIVac-1, HIV-2 WT, and HIVac-2. As sensitive control, THP-1 cells were infected with MLV viruses RV(CL10A1) (TRIM5α resistant) and RV(CIG3N) (TRIM5α sensitive) encoding GFP and pseudotyped with VSV-G (n = 4, paired t test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

See also Figure S4.

CypA Restricts HIVac Capsids at Nuclear Import

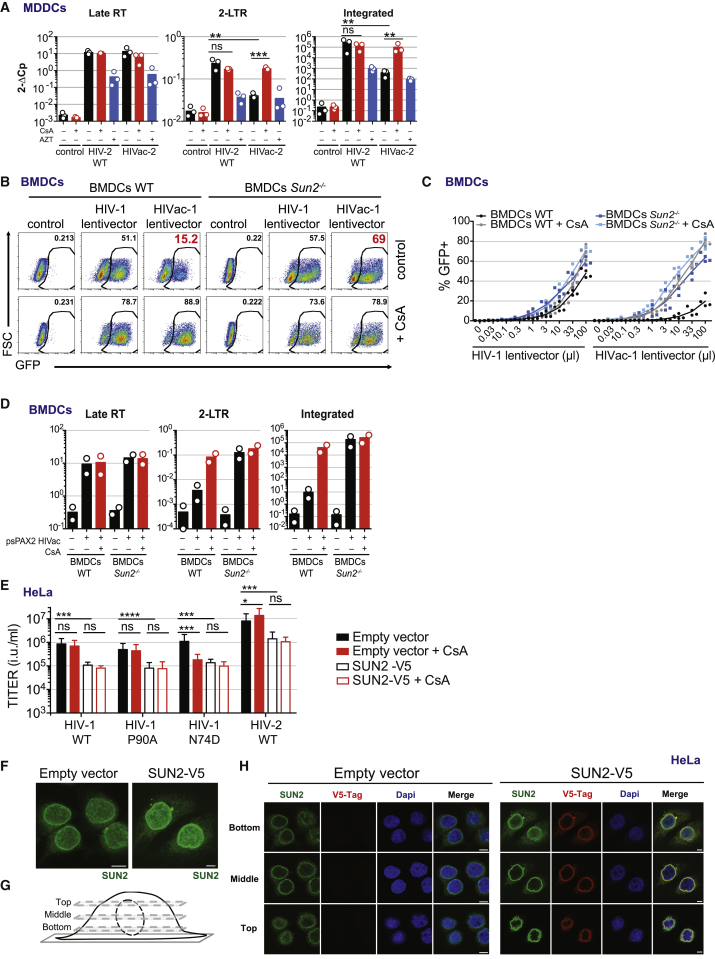

Next, we examined at which stage CypA inhibits infection with HIVac-1 and HIVac-2. In MDDCs, the levels of late reverse transcription products were similar between WT HIV and HIVac viruses (Figures 5A and S5A). However, the levels of 2LTR circles and integrated DNA were reduced for HIVac. Addition of CsA during infection with HIVac-2 restored the formation of 2LTR circles and integrated DNA (Figure 5A). Thus, HIVac viruses progress normally through reverse transcription and are specifically restricted by CypA at the level of nuclear import.

Figure 5.

SUN2 Is Essential for the CypA Restriction of HIVac Capsid

(A) Quantification of late RT, 2LTR circles, and integrated viral cDNA products 24 hr after infection of DCs with HIV-2 WT or HIVac-2. Cells were treated with CsA (2 μM) or AZT (25 μM) (n = 3; paired t test on log-transformed data, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01; ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean).

(B) GFP expression in CD11c+ BMDCs (WT or Sun2−/−) 72 hr after infection with pTRIP-SFFV-GFP lentivectors, pseudotyped with VSV-G, encapsidated by psPAX2 or psPAX2 HIVac mutant and treated or not with CsA (2 μM) (n = 4; representative data for one donor are shown).

(C) Dose response of GFP expression as in (B) (n = 4, line indicates mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(D) Quantification of late RT, 2LTR circles, and integrated viral cDNA products 48 hr after infection of BMDCs (WT or Sun2−/−). Cells were treated with CsA (2 μM) (n = 2; bar, mean).

(E) Titer of indicated viruses on control HeLa cells (Empty vector) or SUN2-overexpressing HeLa cells (SUN2-V5), in the presence or absence of CsA (2 μM) (n = 5, paired RM ANOVA one-way test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant; bar, mean ± SEM).

(F) Maximum intensity z-axis projection of the SUN2 staining (anti-SUN2) in control HeLa cells (Empty vector) or SUN2-overexpressing HeLa cells (SUN2-V5). Scale bar, 5 μm.

(G) Principle of the confocal image acquisition shown in (H).

(H) DAPI and SUN2 staining (total anti-SUN2 or overexpressed V5-tagged SUN2) in control HeLa cells (Empty vector) or SUN2-overexpressing HeLa cells (SUN2-V5). The three panels (top, middle, and bottom) correspond to the description in Figure 5G (n = 3, representative data for one experiment are shown). Scale bar, 5 μm.

See also Figure S5.

SUN2 Is Required for the CypA Restriction of HIVac Capsids

The CypA-mediated restriction at nuclear import suggested to us that a nuclear envelope protein could be involved. We were intrigued by finding that SUN2 (UNC84B), an inner nuclear membrane protein and member of the Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complex, inhibits HIV infection when it is artificially overexpressed (Schoggins et al., 2011). While SUN2 was suggested to be an IFN-stimulated gene (Schoggins et al., 2011), we found that it is expressed constitutively in THP-1 cells and MDDCs and it is not induced by type I IFN, whereas MX1 and MX2 are (Figure S5B). To test whether SUN2 was required for the CypA restriction, we generated Sun2−/− mouse bone-marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) (Figure S5C) (Lei et al., 2009). In WT BMDCs, the infectivity of HIVac-1 lentivector was reduced compared to HIV-1 WT lentivector, and infectivity could be restored by CsA treatment, validating that the CypA-mediated restriction of HIVac is conserved in mouse cells (Figures 5B, 5C, and S5D). Strikingly, in Sun2−/− BMDCs, infectivity of HIVac-1 lentivector was largely rescued (Figures 5B, 5C, and S5D). Furthermore, we found that viral reverse transcription products of HIVac-1 lentivector were similar between WT and Sun2−/− cells, while 2LTR circles and integrated viral DNA were reduced in WT cells and increased in Sun2−/− cells, in a fashion similar to the one observed with CsA treatment of WT cells (Figure 5D). Thus, SUN2 is an essential host factor for the CypA-mediated restriction of HIVac capsids at nuclear import.

Effect of SUN2 on CypA-Dependent HIV Infection in HeLa Cells

Next, we sought to extend the role of SUN2 to other activities of CypA in HIV infection. We generated HeLa cells stably overexpressing SUN2 (Figure S5E). SUN2 inhibited the infection of HIV-1 and HIV-2, confirming its antiviral activity when overexpressed (Figure 5E) (Schoggins et al., 2011). In HeLa cells, as expected, HIV-1 WT and HIV-1 P90A are independent of CypA, while HIV-1 N74D depends on CypA for infection (Figure 5E). Overexpression of SUN2 inhibited HIV-1 N74D infection, and CsA treatment did not reduce infectivity further, indicating that SUN2 overexpression functions in the same pathway as CypA in this model (Figure 5E). In these cells, which were used for infections, we also observed that SUN2 overexpression leads to nuclei that are ruffled and less circular, supporting the notion that an optimal nuclear envelope structure is required for HIV infection through SUN2 (Figures 5F–5H).

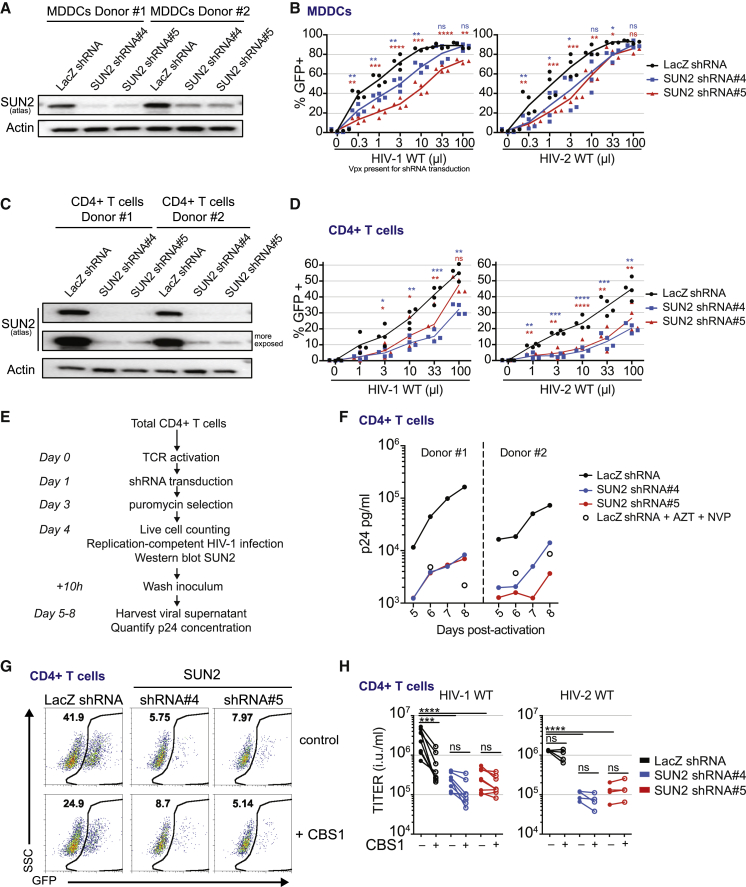

Role of SUN2 in Primary CD4+ Target Cells

Finally, we examined the contribution of endogenous SUN2 to HIV-1 WT and HIV-2 WT infection in primary CD4+ targets and THP-1 cells. In MDDCs, SUN2 knockdown reduced infection by HIV-1 and HIV-2 (Figures 6A and 6B). Although dendritic cells are physiologically relevant target cells for the immune response to the virus, the bulk of viremia in patients is produced by CD4+ T lymphocytes. Depletion of SUN2 in primary activated human CD4+ T cells reduced HIV-1 and HIV-2 infectivity similarly to MDDCs (Figures 6C and 6D). SUN2-depleted cells showed similar viability as compared to control cells (Figures S6A and S6B). Depletion of SUN2 also reduced accumulation of HIV-1 over time using a replication-competent virus (Figures 6E, 6F, S6C, and S6D). In contrast to knockout mouse BMDCs, transient depletion of SUN2 in human MDDCs, CD4+ T cells, and THP-1 cells was not sufficient to rescue HIVac-1 or HIVac-2 infectivity (Figures 6C and S6E–S6G). To determine the contribution of SUN2 to the role of CypA during HIV-1 WT infection, we used the non-immunosuppressive CypA inhibitor, CBS1, in CD4+ T cells (Figure S6H). SUN2 depletion or inhibition of CypA both reduced HIV-1 and HIV-2 infectivity in CD4+ T cells (Figures 6C, 6G, and 6H). Importantly, combining CypA inhibition with SUN2 depletion did not lead to additive inhibition (Figures 6G and 6H). Similar results were obtained in THP-1 cells (Figure S6I). While the CypA inhibitor reduced viral RT cDNA levels in control cells, this effect of the CypA inhibitor was lost in SUN2-depleted cells (Figure S6J). Interestingly, CypA inhibition or SUN2 depletion did not reduce the level of integrated DNA at a detectable level in CD4+ T cells (Figure S6J). Thus, in primary CD4+ T cells, SUN2 is an essential host factor for the positive effects of CypA on reverse transcription and infectivity.

Figure 6.

SUN2 Is an Essential Host Factor of HIV-1 and HIV-2 in Primary CD4+ Target Cells

(A) Western blot analysis of SUN2 and actin expression at the time of infection (day 4) in MDDCs that were transduced at day 0 with shRNA vectors against SUN2 (shRNA#4 or shRNA#5) or a shRNA control vector (LacZ shRNA).

(B) MDDCs as in (A) infected at day 4 with HIV-1 WT or HIV-2 WT. Proportion of GFP-positive cells after 48 hr of infection (n = 4, paired RM ANOVA one-way test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant; LacZ shRNA versus SUN2 shRNA#4 [blue] or SUN2 shRNA#4 [red]; line, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(C) Western blot analysis of SUN2 and actin expression at the time of infection (day 7) in activated CD4+ T cells that were transduced at day 1 with shRNA vectors against SUN2 (shRNA#4 or shRNA#5) or a shRNA control vector (LacZ shRNA).

(D) Activated CD4+ T cells as in (C) infected at day 7 with HIV-1 WT or HIV-2 WT. Proportion of GFP-positive cells after 48 hr of infection (n = 4, paired RM ANOVA one-way test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, LacZ shRNA versus SUN2 shRNA#4 [blue] or SUN2 shRNA#4 [red]; line, mean). Virus inoculum volume is indicated.

(E) Analysis of HIV-1 replication in SUN2-depleted CD4+ T cells over time, outline of the experiment.

(F) HIV-1 p24 concentration at days 5, 6, 7, and 8 in SUN2-depleted CD4+ T cells following infection by replication-competent HIV-1 as in (E) (n = 6; two donors shown; see Figure S6 for four additional donors).

(G) GFP expression in CD4+ T cells 48 hr after infection with HIV-1 WT, encoding GFP in Nef and pseudotyped with VSV-G and in the presence or absence of CBS1 (60 μM) (n = 8; representative data for one donor are shown).

(H) Titers of HIV-1 WT and HIV-2 WT calculated from infections with serial dilutions of viruses as in (G), in the presence or absence of CBS1 (60 μM) (n = 6, except HIV-2 viruses n = 4, paired RM ANOVA one-way test, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant).

See also Figure S6.

Discussion

Here, we show that CypA mediates a conserved restriction against a family of capsid mutants in HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIVmac, and we leverage this phenotype to identify SUN2 as an essential host factor in mediating the activities of CypA on HIV-1 WT infection in primary CD4+ T cells.

The restriction applies to capsid mutants in HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIVmac and has been consistently observed in primary cells and cell lines of human, macaque, and mouse origin. The capsid mutant family is exemplified by the HIVac-2 mutant, which shows a strikingly enhanced affinity for CypA as compared to HIV-2 and is dependent on CypA for inhibition of infection. HIVac-1, an analogous mutant in the CypA-binding loop, is also restricted and dependent on CypA for inhibition, even though the enhanced affinity is less striking (Lahaye et al., 2013). Importantly, the mutant viruses display normal capsids at the structural level (Lahaye et al., 2013) and proceed normally through RT, unlike other CypA-binding mutants such as G89V and P90A (Braaten et al., 1996), indicating that inhibition of their infectivity does not result from gross structural defects. As expected, viral mutants with a strong susceptibility to CypA-mediated restriction are rapidly counter-selected in nature: HIV-1 WT escapes this antiviral mechanism and genetic alteration in the virus is required to reveal it, in accordance with the principle of restriction factors (Malim and Bieniasz, 2012). Interestingly, our results show that HIV-2 is slightly restricted by CypA, indicating that it has not acquired a complete resistance to this antiviral mechanism.

The restriction of HIVac capsids occurs after reverse transcription and before nuclear import. We propose that the acquisition of the ability of lentiviruses to enter the nucleus of non-dividing cells (Goldstone et al., 2010, Lin and Emerman, 2006) offered an opportunity for co-evolution of a host defense mechanism that inhibits lentiviral nuclear import, which can be revealed by the family of capsid mutants described herein.

The combined observations that HIVac capsids are inhibited at nuclear import and that the nuclear envelope protein SUN2 acts as an antiviral factor in HIV infection when overexpressed prompted us to examine whether SUN2 could play a role in the restriction of HIVac capsids. We show that Sun2 deficiency in knockout mouse cells rescues infectivity of HIVac lentivectors. Even though mouse cells are not natural targets of lentiviruses, the restriction mediated by CypA was conserved and the rescue of HIVac infectivity in Sun2 knockout cells thus provides a compelling genetic demonstration. Prior to this work, HIV-1 capsid mutants A92E and G94D were selected in the presence of CsA and became dependent on CypA inhibition for replication (Aberham et al., 1996). This led to the hypothesis that a cell-type-specific restriction factor inhibits HIV-1 infection after reverse transcription but before nuclear import. However, unlike the HIVac capsid mutants, A92E and G94D are generally not dependent on CsA in other cell types (De Iaco and Luban, 2014, Qi et al., 2008, Yin et al., 1998), and evidence for the existence of a restriction factor is limited to a very narrow range of cell lines (De Iaco and Luban, 2014, Song and Aiken, 2007). Moreover, it is, so far, not apparent in primary CD4+ target cells of the virus (Qi et al., 2008). CypA was also suggested to modulate HIV-1 restriction specifically in owl monkey cells (Towers et al., 2003), but this was later found to stem from a TRIM5-CypA fusion protein in this species (Nisole et al., 2004, Sayah et al., 2004). In contrast, our results establish a conserved CypA-dependent restriction that is active in primary CD4+ target cells, indicating a weakness point in the viral cycle. Unexpectedly though, SUN2 knockdown in human cells did not rescue HIVac capsids, as opposed to knockout murine BMDCs. We envision three possibilities: (1) transient knockdown of SUN2 differentially impacts the CypA-dependent restriction in cells as compared to the constitutive knockout that may be developmentally compensated; (2) there are underlying species differences between human and mouse SUN2; (3) there are underlying cell-type differences between murine bone-marrow-derived-DCs and human immune cells. We generated CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts of SUN2 in THP-1 cells, but observed an unexpected loss of CypA dependency on HIV-1 infection in this experiment, questioning the applicability of this approach (data not shown). It will be important to develop methods to further manipulate SUN2 expression in HIV target cells.

Looking at known capsid-associated factors, we show that depletion of MX2, TNPO3, CPSF6, NUP153, RANBP2, or TRIM5 do not rescue HIVac-1 or HIVac-2 infectivity. While we cannot exclude that the host factor knockdowns were not sufficient, our inability to detect even a partial rescue, when control infections with wild-type virus or MLV were affected, strongly suggests that none of these factors contributed to the CypA-dependent restriction. Unexpectedly, MX2 was constitutively expressed in THP-1 cells in the absence of type I IFN, and its depletion reduced HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection in PMA-treated cells, suggesting that MX2 may not be antiviral in differentiated myeloid immune cells in the absence of type I IFN. In contrast, the N74D and N73D mutations, which lie in the binding pocket of CPSF6 and NUP153 (Matreyek et al., 2013, Price et al., 2012), rescued HIVac-1 and HIVac-2 infection from CypA restriction. Since CPSF6 or NUP153 knockdown did not lead to similar rescue, it is possible that another host factor binds the same capsid region, or that the mutation causes structural consequences further away from the CPSF6 and NUP153 binding pocket. It will be interesting to evaluate whether depletion of these factors in the context of SUN2 overexpression or depletion differentially impacts infection with HIV-1 WT and capsid mutants.

The restriction of HIVac capsids at nuclear import and their rescue in SUN2 knockout cells is an artificial situation that we leveraged to more broadly understand the natural mechanisms of CypA activities during HIV infection. We provide evidence in two additional models of CypA activities that SUN2 is a key host factor. First, we examined HeLa cells, in which CypA has no effect on HIV-1 WT infectivity but promotes HIV-1 N74D infectivity. Accordingly, SUN2 overexpression in HeLa cells cancels the positive effect of CypA on HIV-1 N74D infectivity. Optimal SUN2 levels are thus required for CypA activity on HIV infection in HeLa cells. This is unlikely to be a non-specific effect of overexpression, because it was selective for HIV-1 N74D, and SUN2 overexpression was previously found to have no impact on several other viruses (Schoggins et al., 2011). Second, we examined the role of SUN2 in mediating the positive effects of CypA on HIV infectivity in primary CD4+ T cells and MDDCs. Using two distinct shRNAs targeting SUN2, we showed that SUN2 is an essential host factor of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection. Furthermore, in CD4+ T cells, SUN2 depletion was not additive with CypA inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity, and it abrogated the CypA dependence of HIV-1 reverse transcription. Interestingly, SUN2 depletion had a strong effect on HIV-1 infectivity but little effect on viral late RT products and integrated cDNA levels at the time point examined. This suggests the possibility that SUN2 may regulate the dynamics of the early steps of replication, integration sites, or viral transcription to impact HIV infectivity, and these possibilities warrant further study. Overall, our results show that, while SUN2 and CypA can mediate a potent restriction of HIVac capsids, HIV-1 WT has evolved to exploit SUN2 and CypA instead of being susceptible to their restriction. Furthermore, SUN2 is required for both HIV-1 and HIV-2 in CD4+ cells, indicating that SUN2 is an essential HIV-associated factor, including but not limited to CypA activities.

The ability of artificial SUN2 overexpression to inhibit HIV was previously reported in several transformed cell lines and in MDDCs (Donahue et al., 2016, Schoggins et al., 2011). We now show that endogenous SUN2 mediates CypA activities on infection and that endogenous SUN2 is essential for infection in relevant primary CD4+ T cells.

It is noteworthy that both SUN2 overexpression and depletion reduce HIV-1 WT infection. This suggests a non-linear biphasic response (i.e., hormesis) with the endogenous level of SUN2 being the optimal level for infection. SUN2 levels in various target cells or tissue environments may have been a driving force in selecting an optimal level of CypA affinity in lentiviral capsids. Future studies on SUN2 in HIV infection will require experimental setups that allow a precise control overexpression levels. In HeLa cells, SUN2 overexpression inhibits HIV-1 infection and simultaneously leads to deformation of nuclei that become ruffled and less circular, pointing to a tempting link between nuclear envelope architecture and HIV infectivity. SUN2 does not associate with nuclear pores but connects the nucleoskeleton with the cytoskeleton through nesprins (Liu et al., 2007, Tzur et al., 2006), and it will be important to examine the contribution of these other factors to the effects of CypA during HIV infection.

Since SUN2 is a protein of the inner nuclear membrane of the nuclear envelope, it could potentially interact directly with the nuclear fraction of the viral capsid (Chin et al., 2015). The interaction between the capsid and SUN2 could alternatively be indirect, such as through nuclear lamins or nesprins. SUN2 could thus contribute to viral uncoating in the cytosol, to virus docking on the nuclear pore, to its transport through the nuclear pore, and to its targeting to specific regions of chromatin. All of these possibilities have been shown to depend on binding of the HIV-1 capsid to CypA (Campbell and Hope, 2015).

Overall, our results establish that CypA has a conserved ability to restrict lentiviral infection and that SUN2 is a key host factor in mediating both positive and negative activities of CypA on infection. This enables us to unravel the detailed molecular mechanisms of CypA and SUN2 in the context of HIV infection and extends our understanding of the desirable antiviral defenses that are normally bypassed by HIV-1.

Experimental Procedures

Constructs

The HIV-1 WT construct was NL4-3 ΔvifΔvprΔvpuΔenvΔnef encoding GFP or tagRFP in nef, and the HIV-2 WT construct was ROD9 ΔenvΔnef encoding GFP in nef as previously described (Manel et al., 2010). SIVmac239 WT construct was SIVmac239 ΔenvΔnef encoding GFP in Nef. Mutants HIV-1 N74D, HIV-1 V86I-IAP91LPA-M96L (HIVac-1), HIVac-1 N73D, HIV-2 N73D, HIV-2 P86HA (HIVac-2), P86RA, P86QA, P86AA, P86AM, P86HV, P86PI, HIvac-2 N73D, SIVmac239 QPAPQQ85IHAGPLPA, and psPAX2 variant (HIVac-1 mutation) were generated by overlapping PCR mutagenesis. In all final constructs, the entire DNA fragments originating from the PCR and encompassing the restriction sites used for cloning were fully verified by sequencing. Plasmid DNA was purified using with the low endotoxin HiPure plasmid kit (Invitrogen). Recombinant plasmid DNA did not induce dendritic cell maturation, and viral-producing cells were washed after DNA transfection.

Cells

GHOST (GHOST X4R5), 293FT, and HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), and penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). THP-1 and Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI medium, 10% FBS (Gibco), and penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), and THP-1 cells were differentiated with 30 ng/ml (50 nM) of PMA for 16 hr. CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD14+ monocytes were isolated from adult human blood. DCs were generated from blood CD14+ monocytes using granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-4 (IL-4).

Virus Production

Viral particles were produced by transfection of 293FT cells in 6-well plates with 3 μg DNA and 8 μl TransIT-293 (Mirus Bio) per well. One day after transfection, media was removed, cells were washed once, and fresh media was added. Viral supernatants were harvested 1 day later, filtered at 0.45 μM, used fresh or aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. Viral titers were measured on GHOST cells titration as previously described (Manel et al., 2010). RT activity in viral supernatants was measured using the SG-PERT assay (Pizzato et al., 2009) using M-MuLV RT (Finnzyme) as a standard. Viral supernatants did not induce dendritic cell activation in the absence infection.

Infections

At day 4 of MDDC differentiation (or day 7 for BMDCs), cells were harvested, counted, and resuspended in fresh medium at a concentration of one million per ml with 5 μg/ml polybrene, GM-CSF, and IL-4 (or in BMDCs DC medium); 100 μl were aliquoted in round-bottomed 96-well plates, and virus dilutions and treatments were added. 48 hr after infection, cell-culture supernatants were harvested and UV-irradiated to inactivate free virus. For CD4+ T cells infection, activated cells were harvested, counted, and resuspended in fresh medium at a concentration of 0.25 million per ml with 8 μg/ml protamine. 100 μl of cells was aliquoted in round-bottomed 96-well plates, and virus dilutions and treatments were added. 48 hr after infection, cells were fixed and analyzed. HeLa were infected similarly to GHOST cells as previously described (Manel et al., 2010) with 8 μg/ml protamine.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in Prism (GraphPad). The paired t test or paired repeated measures (RM) ANOVA one-way test were used, unless indicated otherwise in figure legends. In figures, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Author Contributions

N.M. and X.L. designed the study. X.L. performed most of the experiments. N.M., T.S., M.G., and A.S. performed some experiments. S.C. set up shRNA transduction in CD4+ T cells. C.C. provided technical help. A.A.-B., J.-F.G., and J.-M.P. provided CBS1. E.C.R., M.C.K., and M.P. provided mouse cells. N.B. and R.L.G. provided adult macaques peripheral blood.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Derek Rookhuizen, Anvita Bhargava, and Philippe Benaroch for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Alice Williart, Maximilien Grandclaudon, and François-Xavier Gobert for technical assistance. We thank the Cytometry facility and the BSL3 facility of Institut Curie. We thank Jean-Luc Battini, Vineet KewalRamani, Greg Towers, and the NIH AIDS Reagent Program for the generous gift of reagents. This work was supported by ATIP-Avenir program, Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS), Ville de Paris Emergence program, European FP7 Marie Curie Actions grant 268311, LABEX VRI (ANR-10-LABX-77), LABEX DCBIOL (ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL∗ and ANR-11-LABX-0043), ACTERIA Foundation, Fondation Schlumberger pour l’Education et la Recherche (FSER), and European Research Council grant 309848 HIVINNATE to N.M.; Sidaction fellowships to A.S. and S.C.; FRISBI (ANR-10-INSB-05-01) and UE FEDER 48748 to J.-F.G.; EQUIPEX FlowCyTech (ANR-10-EQPX-02-01) and INBS IDMIT (ANR-11-INBS-0008) to R.L.G.

Published: April 14, 2016

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, six figures, and five tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.074.

Supplemental Information

References

- Aberham C., Weber S., Phares W. Spontaneous mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene that affect viral replication in the presence of cyclosporins. J. Virol. 1996;70:3536–3544. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3536-3544.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose Z., Lee K., Ndjomou J., Xu H., Oztop I., Matous J., Takemura T., Unutmaz D., Engelman A., Hughes S.H., KewalRamani V.N. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid mutation N74D alters cyclophilin A dependence and impairs macrophage infection. J. Virol. 2012;86:4708–4714. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05887-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieniasz P.D. Intrinsic immunity: a front-line defense against viral attack. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billich A., Hammerschmid F., Peichl P., Wenger R., Zenke G., Quesniaux V., Rosenwirth B. Mode of action of SDZ NIM 811, a nonimmunosuppressive cyclosporin A analog with activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1: interference with HIV protein-cyclophilin A interactions. J. Virol. 1995;69:2451–2461. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2451-2461.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock M., Bishop K.N., Towers G., Stoye J.P. Use of a transient assay for studying the genetic determinants of Fv1 restriction. J. Virol. 2000;74:7422–7430. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7422-7430.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco D.A., Eisenmesser E.Z., Pochapsky S., Sundquist W.I., Kern D. Catalysis of cis/trans isomerization in native HIV-1 capsid by human cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5247–5252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082100499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braaten D., Luban J. Cyclophilin A regulates HIV-1 infectivity, as demonstrated by gene targeting in human T cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:1300–1309. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braaten D., Franke E.K., Luban J. Cyclophilin A is required for an early step in the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 before the initiation of reverse transcription. J. Virol. 1996;70:3551–3560. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3551-3560.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass A.L., Dykxhoorn D.M., Benita Y., Yan N., Engelman A., Xavier R.J., Lieberman J., Elledge S.J. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319:921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E.M., Hope T.J. HIV-1 capsid: the multifaceted key player in HIV-1 infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:471–483. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin C.R., Perreira J.M., Savidis G., Portmann J.M., Aker A.M., Feeley E.M., Smith M.C., Brass A.L. Direct visualization of HIV-1 replication intermediates shows that Capsid and CPSF6 modulate HIV-1 intra-nuclear invasion and integration. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1717–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Iaco A., Luban J. Cyclophilin A promotes HIV-1 reverse transcription but its effect on transduction correlates best with its effect on nuclear entry of viral cDNA. Retrovirology. 2014;11:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nunzio F., Danckaert A., Fricke T., Perez P., Fernandez J., Perret E., Roux P., Shorte S., Charneau P., Diaz-Griffero F., Arhel N.J. Human nucleoporins promote HIV-1 docking at the nuclear pore, nuclear import and integration. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue D.A., Amraoui S., di Nunzio F., Kieffer C., Porrot F., Opp S., Diaz-Griffero F., Casartelli N., Schwartz O. SUN2 overexpression deforms nuclear shape and inhibits HIV. J. Virol. 2016 doi: 10.1128/JVI.03202-15. Published online February 10, 2016. JVI.03202-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke E.K., Yuan H.E., Luban J. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:359–362. doi: 10.1038/372359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganser-Pornillos B.K., Chandrasekaran V., Pornillos O., Sodroski J.G., Sundquist W.I., Yeager M. Hexagonal assembly of a restricting TRIM5alpha protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:534–539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013426108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudin R., de Alencar B.C., Arhel N., Benaroch P. HIV trafficking in host cells: motors wanted! Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:652–662. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone D.C., Yap M.W., Robertson L.E., Haire L.F., Taylor W.R., Katzourakis A., Stoye J.P., Taylor I.A. Structural and functional analysis of prehistoric lentiviruses uncovers an ancient molecular interface. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon C., Moncorgé O., Bauby H., Doyle T., Ward C.C., Schaller T., Hué S., Barclay W.S., Schulz R., Malim M.H. Human MX2 is an interferon-induced post-entry inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature. 2013;502:559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilditch L., Towers G.J. A model for cofactor use during HIV-1 reverse transcription and nuclear entry. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014;4:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrecka K., Hao C., Gierszewska M., Swanson S.K., Kesik-Brodacka M., Srivastava S., Florens L., Washburn M.P., Skowronski J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M., Yadav S.S., Bitzegeio J., Kutluay S.B., Zang T., Wilson S.J., Schoggins J.W., Rice C.M., Yamashita M., Hatziioannou T., Bieniasz P.D. MX2 is an interferon-induced inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature. 2013;502:563–566. doi: 10.1038/nature12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan L., Matreyek K.A., Oztop I., Lee K., Tipper C.H., Li X., Dar M.J., Kewalramani V.N., Engelman A. The requirement for cellular transportin 3 (TNPO3 or TRN-SR2) during infection maps to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid and not integrase. J. Virol. 2010;84:397–406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01899-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguette N., Sobhian B., Casartelli N., Ringeard M., Chable-Bessia C., Ségéral E., Yatim A., Emiliani S., Schwartz O., Benkirane M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye X., Satoh T., Gentili M., Cerboni S., Conrad C., Hurbain I., El Marjou A., Lacabaratz C., Lelièvre J.D., Manel N. The capsids of HIV-1 and HIV-2 determine immune detection of the viral cDNA by the innate sensor cGAS in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2013;39:1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Ambrose Z., Martin T.D., Oztop I., Mulky A., Julias J.G., Vandegraaff N., Baumann J.G., Wang R., Yuen W. Flexible use of nuclear import pathways by HIV-1. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K., Zhang X., Ding X., Guo X., Chen M., Zhu B., Xu T., Zhuang Y., Xu R., Han M. SUN1 and SUN2 play critical but partially redundant roles in anchoring nuclei in skeletal muscle cells in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:10207–10212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812037106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.Y., Emerman M. Cyclophilin A interacts with diverse lentiviral capsids. Retrovirology. 2006;3:70. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Pante N., Misteli T., Elsagga M., Crisp M., Hodzic D., Burke B., Roux K.J. Functional association of Sun1 with nuclear pore complexes. J. Cell Biol. 2007;178:785–798. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Pan Q., Ding S., Qian J., Xu F., Zhou J., Cen S., Guo F., Liang C. The interferon-inducible MxB protein inhibits HIV-1 infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:398–410. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luban J., Bossolt K.L., Franke E.K., Kalpana G.V., Goff S.P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell. 1993;73:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malim M.H., Bieniasz P.D. HIV restriction factors and mechanisms of evasion. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006940. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manel N., Hogstad B., Wang Y., Levy D.E., Unutmaz D., Littman D.R. A cryptic sensor for HIV-1 activates antiviral innate immunity in dendritic cells. Nature. 2010;467:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature09337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matreyek K.A., Engelman A. The requirement for nucleoporin NUP153 during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is determined by the viral capsid. J. Virol. 2011;85:7818–7827. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00325-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matreyek K.A., Yücel S.S., Li X., Engelman A. Nucleoporin NUP153 phenylalanine-glycine motifs engage a common binding pocket within the HIV-1 capsid protein to mediate lentiviral infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003693. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan A.M., Saenz D.T., Guevera R., Morrison J.H., Peretz M., Fadel H.J., Hamada M., van Deursen J., Poeschla E.M. A cyclophilin homology domain-independent role for Nup358 in HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003969. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisole S., Lynch C., Stoye J.P., Yap M.W. A Trim5-cyclophilin A fusion protein found in owl monkey kidney cells can restrict HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:13324–13328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404640101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty U., Ignatius R., Bhardwaj N., Pope M. Generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells from precursors in rhesus macaque blood. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;207:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzato M., Erlwein O., Bonsall D., Kaye S., Muir D., McClure M.O. A one-step SYBR Green I-based product-enhanced reverse transcriptase assay for the quantitation of retroviruses in cell culture supernatants. J. Virol. Methods. 2009;156:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A.J., Marzetta F., Lammers M., Ylinen L.M., Schaller T., Wilson S.J., Towers G.J., James L.C. Active site remodeling switches HIV specificity of antiretroviral TRIMCyp. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1036–1042. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A.J., Fletcher A.J., Schaller T., Elliott T., Lee K., KewalRamani V.N., Chin J.W., Towers G.J., James L.C. CPSF6 defines a conserved capsid interface that modulates HIV-1 replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002896. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002896. Published online August 30, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M., Yang R., Aiken C. Cyclophilin A-dependent restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid mutants for infection of nondividing cells. J. Virol. 2008;82:12001–12008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01518-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasaiyaah J., Tan C.P., Fletcher A.J., Price A.J., Blondeau C., Hilditch L., Jacques D.A., Selwood D.L., James L.C., Noursadeghi M., Towers G.J. HIV-1 evades innate immune recognition through specific cofactor recruitment. Nature. 2013;503:402–405. doi: 10.1038/nature12769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini M., Potash M.J. Novel activities of cyclophilin A and cyclosporin A during HIV-1 infection of primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J. Immunol. 2006;177:443–449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayah D.M., Sokolskaja E., Berthoux L., Luban J. Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature. 2004;430:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller T., Ocwieja K.E., Rasaiyaah J., Price A.J., Brady T.L., Roth S.L., Hué S., Fletcher A.J., Lee K., KewalRamani V.N. HIV-1 capsid-cyclophilin interactions determine nuclear import pathway, integration targeting and replication efficiency. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002439. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoggins J.W., Wilson S.J., Panis M., Murphy M.Y., Jones C.T., Bieniasz P., Rice C.M. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolskaja E., Luban J. Cyclophilin, TRIM5, and innate immunity to HIV-1. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolskaja E., Sayah D.M., Luban J. Target cell cyclophilin A modulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity. J. Virol. 2004;78:12800–12808. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12800-12808.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Aiken C. Analysis of human cell heterokaryons demonstrates that target cell restriction of cyclosporine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants is genetically dominant. J. Virol. 2007;81:11946–11956. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00620-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M., Owens C.M., Perron M.J., Kiessling M., Autissier P., Sodroski J. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thali M., Bukovsky A., Kondo E., Rosenwirth B., Walsh C.T., Sodroski J., Göttlinger H.G. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:363–365. doi: 10.1038/372363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers G.J., Hatziioannou T., Cowan S., Goff S.P., Luban J., Bieniasz P.D. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV-1 to host restriction factors. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nm910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzur Y.B., Wilson K.L., Gruenbaum Y. SUN-domain proteins: ‘Velcro’ that links the nucleoskeleton to the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:782–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgen C.A., Kratovac Z., Bieniasz P.D., Hatziioannou T. Independent genesis of chimeric TRIM5-cyclophilin proteins in two primate species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3563–3568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M., Emerman M. Capsid is a dominant determinant of retrovirus infectivity in nondividing cells. J. Virol. 2004;78:5670–5678. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5670-5678.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Aiken C. A mutation in alpha helix 3 of CA renders human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cyclosporin A resistant and dependent: rescue by a second-site substitution in a distal region of CA. J. Virol. 2007;81:3749–3756. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02634-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Braaten D., Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication is modulated by host cyclophilin A expression levels. J. Virol. 1998;72:6430–6436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6430-6436.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S., Myszka D.G., Yeh C., McMurray M., Hill C.P., Sundquist W.I. Molecular recognition in the HIV-1 capsid/cyclophilin A complex. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;269:780–795. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.