Abstract

Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) is a cyclic peptide highly conserved in vertebrates and was originally identified as a skin-paling factor in Teleosts. In fishes, MCH also participates in the regulation of the stress-response and feeding behaviour. Mammalian MCH is a hypothalamic neuropeptide that displays multiple functions, mostly controlling feeding behaviour and energy homeostasis. Transgenic mouse models and pharmacological studies have shown the importance of the MCH system as a potential target in the treatment of appetite disorders and obesity as well as anxiety and psychiatric diseases. Two G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) binding MCH have been characterized so far. The first, named MCH-R1 and also called SLC1, was identified through reverse pharmacology strategies by several groups as a cognate receptor of MCH. This receptor is expressed at high levels in many brain areas of rodents and primates and is also expressed in peripheral organs, albeit at a lower rate. A second receptor, designated MCH-R2, exhibited 38% identity to MCH-R1 and was identified by sequence analysis of the human genome. Interestingly, although MCH-R2 orthologues were also found in fishes, dogs, ferrets and non-human primates, this MCH receptor gene appeared either lacking or non-functional in rodents and lagomorphs. Both receptors are class I GPCRs, whose main roles are to mediate the actions of peptides and neurotransmitters in the central nervous system. However, examples of action of MCH on neuronal and non-neuronal cells are emerging that illustrate novel MCH functions. In particular, the functionality of endogenously expressed MCH-R1 has been explored in human neuroblastoma cells, SK-N-SH and SH-SY5Y cells, and in non-neuronal cell types such as the ependymocytes. Indeed, we have identified mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent or calcium-dependent signalling cascades that ultimately contributed to neurite outgrowth in neuroblastoma cells or to modulation of ciliary beating in ependymal cells. The putative role of MCH on cellular shaping and plasticity on one side and volume transmission on the other must be now considered.

Keywords: AROM gene; energy balance; feeding behaviour; melanin-concentrating hormone; MCH receptors; primate-specific PMCHL genes

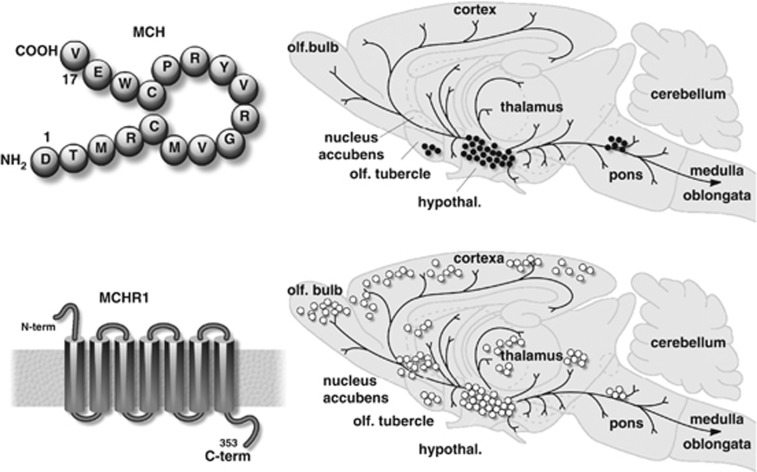

Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) is a cyclic peptide that was first isolated from salmon pituitary glands1 and subsequently characterized in the rat hypothalamus.2 Brain and peripheral expression of MCH was then established in many mammalian species including humans (reviewed in Nahon et al.3). In the central nervous system, MCH mRNA and peptide syntheses were found predominantly in neurons of the lateral hypothalamus and zona incerta that projected throughout the brain4, 5 (Figure 1, reviewed in Bittencourt6). Central MCH displayed a wide range of functions (reviewed in Nahon et al.,3 Griffond and Baker,7 Pissios et al.,8 Adamantis and de Lecea9), with a major role in energy maintenance by decreasing energy expenditure and stimulating feeding behaviour10 (see below). Two high-affinity receptors for MCH have been identified (reviewed in Hervieu 11 and Chung et al. 12). The first receptor, named here MCH-R1, also called SLC1, was simultaneously identified through reverse pharmacology strategies by several groups as a cognate receptor of MCH.13, 14, 15, 16 This receptor is expressed at high levels in many brain areas of rodents and primates13, 17 and is also expressed in peripheral organs, albeit at a lower rate. A second receptor, designated here as MCH-R2, exhibits 38% identity to the MCH-R1 and was originally identified in humans18 (reviewed in Boutin et al.19). Interestingly, although MCH-R2 orthologues were also found in fishes, dogs, ferrets and non-human primates, this MCH receptor gene appeared either lacking or non-functional in Glire species (including rodents and lagomorphs).20, 21 Both receptors are class I G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), whose main role is to mediate the actions of peptides and neurotransmitters in the central nervous system. We present here an overview of recent studies concerning the effect of MCH on feeding behaviour and energy storage, the MCH gene(s) and complex regulation in primates particularly and finally the MCH receptor family and functional characterization in cells expressing exogenous or endogenous MCH-R1 or MCH-R2.

Figure 1.

Structure and brain distribution of the rat MCH and MCH-R1. Left panels: structure of the rat MCH (cyclic peptide) and rat MCH-R1 (7TM GPCR); right panels: sagittal sections of the rat brain showing the distribution of MCH neurons and projections and MCH-R1 mRNA expression. Black dots indicate MCH neuron perikarya, and lines correspond to fibres. Brain areas with expression of MCH-R1 mRNA are noted by white dots, redrawn, respectively, from Bittencourt et al.5 and Hervieu et al.17

MCH is involved in energy homeostasis control and many motivated behaviours

The dominant expression of MCH in the lateral hypothalamus of mammalian brains, a so-called feeding–drinking centre, has generated the proposal that this peptide may regulate appetite and/or energy homeostasis. The role of MCH and MCH-R1 signalling in the control of feeding behaviour and energy balance is now firmly established in rodents (reviewed in Pissios et al.,8 Qu et al.,10 Hervieu et al.,17 Nahon,22 Pissios23).

Acute intracerebroventricular injections of MCH (>5 μg per animal) transiently stimulate food intake in rats, an orexigenic effect that is not mediated by neuropeptide Y, galanin or orexins (also named hypocretins) but could be blocked by α-MSH. Intrahypothalamic injection studies and electrophysiological characterization further identified the paraventricular nucleus, ventromedian nucleus and arcuate nucleus as major targets of MCH action, with differential effects in small-litter and overnourished rats. Interestingly, MCH also stimulates water consumption independently from its feeding and water osmolality actions, consistent with the strong adipsia observed in LHA-lesioned rats. Chronic intracerebroventricular infusion of MCH in rats or mice induces hyperphagia and body weight gain, especially on a moderate high-fat diet. The development of obesity is accompanied by an increase in liver and adipose tissue weights and an accompanying increase in lipogenic activity in white adipose tissue and concomitant reduction in brown adipose tissue functions. Furthermore, plasma glucose, insulin and leptin levels are also increased in these animals, all these parameters being associated with obesity in men. Furthermore, central administration of MCH-R1 antagonists leads to a sustained reduction in appetite, body weight and fat storage without overt alteration of lean mass. Peripheral MCH-R1 signalling may also be involved in this process through regulation of leptin or insulin secretion. Finally, in agreement with the pharmacological data, genetically modified mouse models also showed an important role of MCH and MCH-R1 genes in appetite and, mainly, energy metabolism. Indeed, transgenic mice overexpressing the MCH gene develop hyperphagia, mild obesity and insulin resistance when maintained on a high-fat diet. Conversely, MCH gene ablation in mice leads to a leanness phenotype associated with hypophagia and an increase in oxygen consumption, both effects being highly dependent upon the genetic background and diet. In this regard, the reduction in body fat observed in mice combining MCH and leptin deficiencies, by crossing MCH-null mice and ob/ob mice, does not result from feeding behaviour changes (the mice remaining hyperphagic) but from improvements in energy expenditure regulation (increased locomotor activity and resting metabolic rate). It is worth noting that targeted disruption of the MCH-R1 gene in mice maintained on regular chow also leads to a lean phenotype associated with both hyperphagia on one hand and increased energy metabolism on the other. In agreement with the hyperactive phenotype, MCH-R1-null mice are resistant to high-fat diet-induced obesity.

Overall, pharmacological studies and animal models have shown that MCH and MCH-R1 neuronal networks have a major role in the control of energy homeostasis by increasing food intake and mostly regulating energy expenditure and thermogenesis in mammals. However, the actions of MCH appear much more widespread and concern a large spectrum of behaviours. These include sleep–wake regulation, sexual behaviour, grooming, rearing, aggressive behaviour, locomotion, exploratory behaviour, learning and memory formation (these behavioural studies are discussed in exhaustive reviews7, 8, 9, 11, 17, 24, 25). Recent studies (reviewed in Kemp and Weetman26 and Lakaye27) also addressed the local expression and role of MCH and its receptor outside the brain. Indeed, the importance of MCH/MCH-R1 in the digestive tract, adipose and bone tissues and cardiovascular and immune systems, for instance, should be considered in analysing phenotype alterations in MCH-null or -overexpressing transgenic mice.

Complex structure of the precursor MCH mRNA and sense/antisense genes

Two MCH genes and/or corresponding mRNAs have been originally cloned and sequenced from salmonids, tilapia, bonito, eel and flounder.28 Both were intronless and displayed the highest level of substitutions when compared within the same species rather than among other species, in agreement with early tetraploidization during teleost fish evolution. The salmonid and tilapia/flounder preproMCHs are 132 and 135 amino acids long, respectively, with the MCH peptide located at the C terminus. In contrast with the strong conservation in the MCH region between teleost fish species, the remaining part of the precursor displays marked sequence divergences.29, 30 However, additional putative peptides could be generated from the teleost fish proMCH and named MCH-gene-related peptide (Mgrp) in tilapia, Neuropeptide-E (glutamic acid)-V (valine; NEV) in chum salmon or Neuropeptide-A(alanine)-L (leucine) in barfin flounder; however, their functional importance, if any, remains elusive. Recently, a second MCH gene was identified in the genome databases of zebrafish, fugu, three-spined stickleback and medaka.30 This gene, named Pmch2, shares striking similarities with the mammalian MCH gene in terms of structure, genomic synteny and peptide sequence (19–25 amino acids in length). Two different MCH peptides can be expressed in distinct regions of the zebrafish hypothalamus. Although both MCH peptides could have a role in pigmentation,31 preliminary functional studies in zebrafish indicate that the Pmch2-derived MCH peptide could be selectively involved in food intake regulation, as in mammals. Recently, a single MCH gene was found in the scalloped hammerhead shark Sphyrna lewini, and shark MCH peptide displayed strong similarities in term of structure and brain distribution to mammalian counterparts as well as under stress responses,32 indicating that the ancestral intronic MCH gene may be involved in functions similar to those found in mammals.

The sequence of the single gene encoding the full MCH precursor comprises three exons and two introns and exhibits high conservation in mammalian species. In humans, this gene is located on chromosome 12q24 covering ∼1.4kb of genomic DNA. The first exon encodes the 5′-untranslated region of the mRNA and the N-terminal part of proMCH including the signal peptide that allows targeting to the secretory pathway. The second exon consists of the sequence corresponding to putative neuropeptide(N)-glycine(G)-glutamic acid(E) (NGE), neuropeptide(N)-glutamic acid(E)-isoleucine(I) (NEI) and the first three amino acids of MCH. The last 15 amino acids of MCH and the 3′-untranslated amino acids are localized in exon III. Intron B splits the methionine codon with the nucleotides A on exon II and the TG on exon III. This intronic organization is identical in the rat, mouse and primate MCH genes. This unusual intron position for a neuropeptide-encoding gene is of primary importance for generating by alternative splicing a short mRNA encoding a protein named MCH-gene-overprinted-polypeptide (MGOP),33 whose function remains elusive.

In addition to the MCH/MGOP gene, two other MCH gene-related transcription units were found in mammalian genomes. First, characterization of high-molecular-weight transcripts recognized by MCH complementary DNA/oligoprobes in the pheochromocytoma PC12 cell line and rat tissues revealed the existence of ‘natural' antisense RNAs transcribed from the genomic region complementary to the MCH gene. This new gene was named AROM (Antisense-RNA-Overlapping-MCH).34 Two major classes of RNAs appear produced from the AROM gene: (1) non-coding unspliced RNAs overlapping exon II/exon III and flanking intronic/regulatory sequences of the MCH gene; and (2) alternatively spliced mRNAs complementary to the 3′-flanking region of the MCH gene and coding for a new family of RNA/DNA-binding proteins. One of these proteins, named PARI, is involved in the control of genomic stability and correct DNA repair.35 Because of the reciprocal regulation of MCH and AROM gene expression in PC12 cells, it is tempting to speculate that AROM mRNA and/or proteins may control the MCH gene expression, but this remains to be directly tested.

The primate-specific PMCL1/PMCHL2 genes encode non-coding RNAs that regulate MCH gene expression

A decade ago we provided evidence for the emergence of two chimeric genes in higher primates.36 These genes were named PMCHL1 and PMCHL2, based on partial homology with the authentic MCH gene, and were found, respectively, on human chromosomes 5p14 and 5q13; that is, they were located on chromosomal regions clearly distinct from this of the genuine MCH gene. Detailed structural expression and phylogenetic analyses showed that the PMCHL1 gene was created about 25 million years ago (mya) by a complex mechanism of exon-shuffling through retrotransposition of an antisense MCH messenger RNA coupled to de novo creation of splice sites. PMCHL2 arose 5–10 mya by an event of duplication involving a large chromosomal region encompassing the PMCHL1 locus. Interestingly, both sense and antisense transcripts from the PMCHL1 gene are expressed in different areas of the developing human brain, whereas the PMCHL2 gene is totally silent in the central nervous system. Strikingly, most of the PMCHL1/PMCHL2 mRNAs expressed in primate testis or brain appeared as long non-coding RNAs (our unpublished data). In particular, we have identified two unconventional RNAs that displayed tissue and developmental-stage specificities in the primate brain, with highest expression in the cerebral cortex. The first one is composed of a PMCHL1 sense part and an antisense part, and the second one is composed of two PMCHL1 sense parts but in reverse order. We have established, therefore, cell lines expressing these unconventional transcripts and we investigated further the mechanism underlying the formation of these transcripts and their mode of action. Given the absence of the canonical (GU/AG) splice donor and acceptor sites, our hypothesis was that these transcripts were the result of trans-splicing events that used short complementary sequences. We initiated a mutagenesis approach, in which the different sequence elements were mutated, stably expressed in HEK293 cells and trans-spliced transcripts were analysed. Surprisingly, MCH mRNA expression was found driven by non-mutated trans-spliced transcripts in transfected HEK293 cells as well as in the macaque cortex (our unpublished data). In summary, we have identified unconventional trans-spliced transcripts of the PMCHL gene that lead to tissue and developmental-stage expression of the targeted MCH mRNA in primate brain areas outside the hypothalamus. Primate-specific origination of long non-coding RNA-encoding genes that regulate MCH gene expression may contribute to phenotypic traits that would be unique to the human lineage, but this needs further elaboration. The PMCHL1 gene represents a prototype of the so-called ‘primate-specific' genes that are presently under intensive investigation because of their major interest in understanding the basis of human evolution and emergence of novel functions.

MCH-R1 structure and signalling

A milestone discovery in the MCH receptor field was the quite simultaneous identification by several laboratories in 1999 of an orphan GPCR called SLC-1 (GPR24) as being a bona fide MCH receptor, named here MCH-R1.13, 14, 15, 16 This receptor belongs to the class 1 subfamily of GPCRs and displays strong sequence conservation among mammals (91% protein sequence identity between rats and humans). The MCH-R1 gene consists of two exons that encode for a 353-amino-acid protein with seven putative transmembrane domains, three N-glycosylation sites in the N-terminal part, which appear necessary for cell surface targeting, and multiple phosphorylation sites in the intracellular loops; some of them, located in its C-terminal tail, are involved in the MCH-dependent internalization of MCH-R1. This receptor is widely and strongly expressed in rat, mouse and primate brains with a distribution that matches with the MCH projection fields, suggesting that this receptor may mediate most MCH actions in mammals (reviewed in Hervieu et al.17).

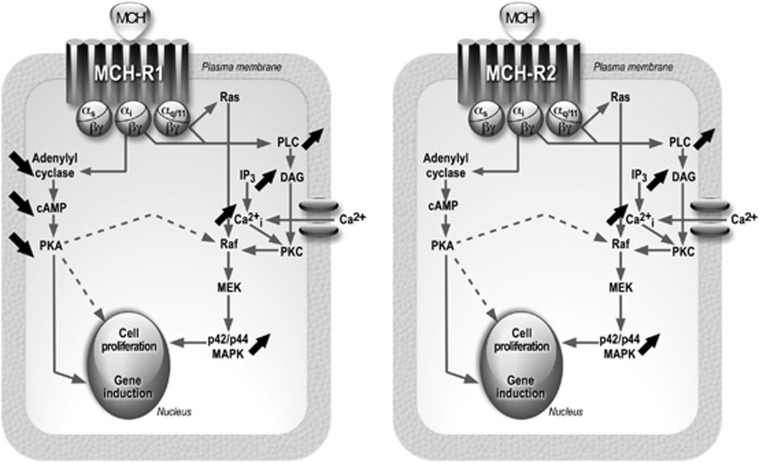

In cells expressing exogenous receptor, MCH-R1 binds MCH with nanomolar affinity and may couple to Gi, Go and Gq proteins to activate multiple intracellular signalling pathways37 (reviewed in Hervieu et al.17). For example, in CHO or HEK293 cells transfected with MCH-R1, MCH inhibits the forskolin-stimulated production of cAMP and activates mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK; Figure 2, left panel). MCH may also stimulate IP3 production and induce an increase in intracellular ‘free' Ca2+ levels via a Gαq interaction. Pretreatment with pertussis toxin (PTX), which blocks Gαi/Gαo proteins, abolishes the MCH-stimulated inhibition of cAMP production and MAPK activation but only decreases the intracellular Ca2+ efflux. Intriguingly, combination of MCH with forskolin potentiates MAP kinase phosphorylation in HEK293 cells stably expressing MCH-R1 and in various regions of the rat brain,37 suggesting that a complex interaction between MCH-R1 and receptors coupled to Gαs could be the rule rather than the exception in the mammalian brain.

Figure 2.

Representations of the main MCH receptor (MCHR1 or MCH-R2) signalling pathways in mammalian cells. Left panel: MCHR1 signalling pathways; right panel; MCH-R2 signalling pathways. The MCH receptors may couple to different G-proteins, including Gi, G0 and Gq/11. Activation of Gi results in a decrease in adenylate cyclase activity and a reduction in cAMP formation (descending arrows). Activation of G0 (not shown) or Gq/11 results in MAPK activation via Ras/Raf activation and elevation of Ca2+i concentrations via IP3 and PLC/PKC activations (rising arrows). Activation of these cascades would ultimately lead to changes in gene transcription and cell proliferation/differentiation (see text).

In contrast to these results, the signalling pathways that mediate MCH action in mammalian cells endogenously expressing MCH-R1 remain poorly explored except in neuroblastoma or melanoma cell models (reviewed in Eberle et al.38). Indeed, in human melanoma SK-MEL-37 cells, MCH inhibited forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation and induced MAPK phosphorylation in a PTX-sensitive manner, suggesting the coupling to Gαi/Gαo proteins. The activation of the MAPK pathway led to the production of active Erk1/Erk2-phosphorylated forms. In contrast, MCH stimulates insulin release in insulinoma cells, CR1–G1 and RINm5F cells, through a PTX-insensitive signalling cascade. Expression of MCH-R1 was also reported for human melanocytes and murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes. In these latter cells, MCH affects leptin expression possibly through activation of Erk1/2 MAPK and pp 70 S6 kinase, suggesting a functional MCH signalling pathway.

Interestingly, both p53 and MAP kinase pathways contribute to mediating the MCH effect through genuine MCH-R1 on neurite outgrowth in human neuroblastoma cells,39 suggesting that MCH may have a role in neuronal cell differentiation and plasticity. Very recently, we characterized the expression and functionality of endogenously expressed MCH-R1 in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells and in primary cultured hypothalamic neurons. We found low levels of expression of this receptor in human neuroblastoma cells, close to physiological conditions. We identified a MAPK-dependent signalling cascade that is activated within a few minutes after MCH exposure. This pathway was also found to be involved in stimulation by MCH of a restricted set of COPII complex-encoding genes contributing likely to transdifferentiation of SK-N-SH cells (our unpublished data). Therefore, this study allowed a complete characterization from early receptor activation to late transcriptome remodelling and cellular shape changes in neuronal or neuron-like cells, for a receptor, MCH-R1, particularly important for controlling neuronal activity associated with feeding behaviour and energy balance.

On the basis of neuro-anatomical mapping and electrophysiological data, it was assumed that synaptic transmission represents the main mode of action of MCH in the brain. However, non-neuronal intercellular communication or ‘volume' transmission through the cerebrospinal fluid flow may also be involved. To address the potential contribution of these mechanisms in driving MCH effects, we first mapped non-neural cells targeted by MCH fibres. We found numerous MCH fibres in close vicinity to ependymocytes of the ventral part of the third ventricle (3V) in Pmch-CFP mice. Then, we demonstrated MCH-R1 mRNA as well as MCH-R1 protein expression in the ventral 3V ependymal cells. Developing new techniques to measure and analyse the ependymal cilia beat frequency (CBF) in acute mouse brain slice preparations, we have shown that the CBF is increased by MCH application on ependymal cells or distantly by LHA stimulation, an effect blocked by a selective MCH-R1 antagonist and absent in MCH-R1-knockout mice. In vitro optogenetic activation or inhibition of MCH neurons further demonstrated a tonic control of these neurons on 3V ependymocytes CBF. Finally, using in vivo brain MRI and in vivo tracking of fluorescent microbeads, we demonstrated that the volume of both the lateral and third ventricles is increased in MCH-R1-knockout mice compared with their wild-type littermates, resulting in faster cerebrospinal fluid flow. Collectively, our data revealed a dynamic control of MCH neurons on spontaneous CBF of MCH-R1-expressing ependymal cells and on cerebrospinal fluid flow in brain ventricles.40, 41

MCH-R2 structure and signalling

The second MCH receptor, named here MCH-R2, was identified in the human genome by use of in silico data mining, and its complementary DNA was subsequently isolated from human brain complementary DNA libraries.18, 19 In contrast to the MCH-R1 gene, which is intronless in its coding region, the MCH-R2 gene encompasses five coding and one noncoding exon and may produce receptor variants by alternative splicing that would lead to a truncated version of MCH-R2. It is noteworthy that human MCH-R1 and MCH-R2 display low sequence identity (only 36%), which is rather unusual for a family of GPCRs that bind an identical ligand, suggesting weak evolutionary constraints. As mentioned above, the MCH-R2 gene is found in teleots (pufferfish, zebrafish), sharks, dogs, ferrets and primates (including human); however, a functional MCH-R2 gene is selectively lost in the rodent/lagomorph lineage. This proved to be useful for elucidating the physiological importance of the single MCH-R1 in rat and mouse but also hampered functional characterization of MCH-R2 in available animal models. Very recently, Maratos-Flier and colleagues42 generated a mouse model in which the human MCH-R2 gene was under the control of the MCHR1 gene promoter, resulting in coexpression in the MCHR1R2 mouse brain. Intriguingly, the MCHR1R2 mice exhibited a resistance to diet-induced obesity due to reduced food intake. Additional investigations with transgenic mice expressing the human MCH-R2 gene under the genuine human promoter should be performed to validate this interesting study.

In mammals, the overall brain expression pattern of MCH-R2 appears to overlap partially with that of MCH-R1 but with a more restricted expression to the limbic regions, including the medial and central amygdala, the entorhinal and temporal cortex, the CA1 of the hippocampus and to a lesser extent in the ventral hypothalamus and claustrum. Nevertheless, arguing for a coexpression in the same cells seems highly speculative. In monkeys, MCH-R2 is strongly expressed in the arcuate and ventromedial hypothalamic nuclei. The differential distribution of the two MCH receptors, particularly in the human brain, may indicate distinct biological roles in mediating the large spectrum of MCH effects. In the periphery, weak MCH-R2 expression is detected in the pituitary, adipose tissue and pancreas, which also express MCH-R1; however, the precise cellular distribution and functional relevance of MCH-R2 in these organs are presently unknown.

The signalling pathways associated with MCH-R2 activation have been studied only in transfected mammalian cells and proved to be much more restricted than those reported for MCH-R1 (Figure 2, right panel). Indeed, MCH causes an increase in intracellular free Ca2+ levels and IP3 production but has no effect on basal or forskolin-induced cAMP synthesis. This action is not blocked by PTX treatment, indicating that MCH-R2 couples mainly to Gαq. The difference in G-protein coupling between MCH-R1 and MCH-R2 could be ascribed to the marked sequence difference in the second and third intracellular loops, which are essential for specific G-protein interaction in the GPCR family.

Conclusion

During the last decade a number of companies have synthesized, tested and patented a variety of non-peptide MCH antagonists acting at MCH-R1 (close to 60 patent applications are presently registered43). As such, the compounds are claimed to be useful in suppressing appetite and in treating or preventing a wide range of diseases, including diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, depression, anxiety and associated somatic symptoms, as well as neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. There is no doubt that, among this large number of compounds, suitable candidates will be identified and subsequently entered into clinical trials. However, major questions remain about the role of MCH and MCH-R1 in the control of energy balance (for example, phenotype discrepancy between MCH- and MCH-R1-null mice, role of synaptic versus volume transmission in mediating brain MCH effects) and other behaviours (stress response, sexual activity, sleep and learning). Furthermore, the MCH physiological functions mediated by MCH-R2 in the human brain deserve thorough investigations and the development of suitable animal models.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated in memory of Professor Wylie Vale, a pioneer in the MCH field and a major contributor in Neuroendocrinology, who passed away in January 2012. We thank Dr Erwan Bezard (IMN, CNRS UMR5293, Bordeaux, France) for his critical reading of and helpful comments on this manuscript. The work carried out in Nahon's laboratory at the IPMC was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the French National Research Agency (ANR-08-MNPS-018-01; LABEX SIGNALIFE, ANR-11-LBX-0028-01), 6th FP EU STREPS/NEST, (APES project no. 28594), the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), the Fondation de France (Comité Parkinson), the ‘Association France Parkinson', the ‘Société Française de Nutrition', the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) and the <<Convention de Collaboration>> IUCPQ-Université Laval (Québec)/CNRS. We thank Professor Jeffrey M Friedman (Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA) for kindly providing the Pmch-CFP mice and Dr A Viale (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA) for having performed microarray experiments and data analysis. Gregory Conductier was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from ANR-08-MNPS-018-01, the CNRS (INSB), the Société Française de Nutrition (prize winner 2010) and the Danone Institute (prize winner 2012).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article is published as part of a supplement sponsored by the Université Laval's Research Chair in Obesity in an effort to inform the public on the causes, consequences, treatments and prevention of obesity.

References

- Kawauchi H, Kawazoe I, Tsubokawa M, Kishida M, Baker BI. Characterization of melanin concentrating hormone in chum salmon pituitaries. Nature 1983; 305: 321–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan JM, Fischer WH, Hoeger C, Rivier J, Vale W. Characterization of melanin-concentrating hormone from rat hypothalamus. Endocrinology 1989; 125: 1660–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahon JL. The melanin-concentrating hormone: from the peptide to the gene. Crit Rev Neurobiol 1984; 8: 221–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahon JL, Presse F, Bittencourt JC, Sawchenko PE, Vale W. The rat melanin-concentrating hormone messenger ribonucleic acid encodes multiple neuropeptides coexpressed in the dorsolateral hypothalamus. Endocrinology 1989; 125: 2056–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt JC, Presse F, Arias C, Peto C, Vaughan J, Nahon JL et al. The melanin-concentrating hormone system of the rat brain: an immuno- and hybridization histochemical characterization. J Comp Neurol 1992; 319: 218–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt JC. Anatomical organization of the melanin-concentrating hormone peptide family in the mammalian brain. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2011; 172: 185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffond B, Baker BI. Cell and molecular cell biology of melanin-concentrating hormone. Int Rev Cytol 2002; 213: 233–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissios P, Bradley RL, Maratos-Flier E. Expanding the scales: the multiple roles of MCH in regulating energy balance and other biological functions. Endocrine Rev 2006; 27: 606–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamantis A, de Lecea L. A role for melanin-concentrating hormone in learning and memory. Peptides 2009; 30: 2066–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu D, Ludwig DS, Gammeltoft S, Piper M, Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ et al. A role for melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behaviour. Nature 1996; 380: 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu GJ. Further insights into the neurobiology of melanin-concentrating hormone in energy and mood balances. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2006; 10: 211–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Parks G, Lee C, Civelli O. Recent updates on the melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) and its receptor system: lessons from MCH1R antagonists. J Mol Neurosci 2011; 43: 115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Nothacker HP, Wang Z, Lin SHS, Leslie F, Civelli O. Molecular characterization of the melanin-concentrating hormone receptor. Nature 1999; 400: 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J, Ames RS, Bergsma D, Muir A, Fitzgerald LR, Hervieu G et al. Melanin-concentrating hormoneis the cognate ligand for the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor SLC-1. Nature 1999; 400: 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bächner D, Kreienkamp HJ, Weise C, Buck F, Richter D. Identification of melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) as the natural ligand for the orphan somatostatin-like receptor 1 (SLC-1). FEBS Lett 1999; 457: 522–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo PMC, Grazzini E, Cao J, Hubatsch DA, Pelletier M, Hoffert C et al. The receptor for the orexigenic peptide melanin-concentrating hormone is a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nat Cell Biol 1999; 1: 267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu G, Maulon-Feraille L, Chambers JK, Cluderay JE, Wilson S, Presse F et al. Trans In: Quirion R, Björklund A, Hökfelt T (eds). Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Peptide receptors, Part II. Vol 20, Elsevier Science: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003, pp 31–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Duckworth M, Murdock P, Rennie G, Sabido-David C, Ames RS et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of MCH2, a novel human MCH receptor. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 20125–20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutin JA, Suply T, Audinot V, Rodriguez M, Beauverger P, Nicolas JP et al. Melanin-concentrating hormone and its receptors: state of the art. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2002; 80: 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CP, Sano H, Iwaasa H, Pan J, Sailer AW, Hreniuk DL et al. Melanin-concentrating hormone receptor subtypes 1 and 2: species-specific gene expression. Genomics 2002; 79: 785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan DW, Bryson-Richardson RJ, Pagan KE, Taylor MS, Currie PD, Jackson IJ. The structure and evolution of the melanocortin and MCH receptors in fish and mammals. Genomics 2003; 81: 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahon JL. The melanocortins and melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behavior and energy homeostasis. C R Biol 2006; 329: 623–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissios P. Animal models of MCH function and what they tell us about its role in energy balance. Peptides 2009; 30: 2040–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamantidis A, de Lecea L. Physiological arousal: a role for hypothalamic systems. Cell Mol Life Sci 2008; 65: 1475–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Sapin E, Leger L, Luppi PH, Fort P. Role of the melanin-concentrating hormone neuropeptide in sleep regulation. Peptides 2009; 30: 2052–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp EH, Weetman AP. Melanin-concentrating hormone and melanin -concentrating hormone receptors in mammalian skin physiopathology. Peptides 2009; 30: 2071–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakaye B, Coumans B, Harray S, Grisar T. Melanin-concentrating hormone and immune function. Peptides 2009; 30: 2076–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffond B, Baker BI. Cell and Molecular cell biology of melanin-concentrating hormone. Int Rev Cytol 2002; 213: 233–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaud B, Darré-Toulemonde F, Duhault J, Boutin JA, Nahon JL. Comparative analysis of melanin-concentrating hormone structure and activity in fishes and mammals. Peptides 2004; 25: 1623–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J, Skariah G, Maro GS, Mignot E, Mourrain P. Characterization of two melanin-concentrating hormone genes in zebrafish reveals evolutionary and physiological links with the mammalian MCH system. J Comp Neurol 2009; 517: 695–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Song Y, Thompson DA, Madonna MA, Milhauser GL, Toro S et al. Pineal-specific agouti protein regulates teleost background adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 20164–20171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizusawa K, Amiya N, Yamaguchi Y, Takabe S, Amano M, Breves JP et al. Identification of mRNAs coding for mammalian-type melanin-concentrating hormone and its receptors in the scalloped hammerhead shark Sphyrna lewini. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2012; 179: 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaeys I, Bouyer K, Loudes C, Faivre-Bauman A, Petit F, Ortola C et al. Characterization of MCH-gene overprinted-polypeptide-immunoreactive material in hypothalamus reveals an inhibitory role of pro-somatostatin1-64 on somatostatin secretion. Eur J Neurosci 2004; 19: 925–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsu L, Presse F, Nahon JL. The AROM gene: spliced mRNAs encoding new DNA/RNA binding proteins are transcribed from the opposite strand of the melanin-concentrating hormone gene in mammals. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 40576–40587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan GL, Dejsuphong D, Petalcorin MIR, Hofmann K, Takeda S, Boulton SJ et al. Inhibition of homologous recombination by the PCNA-interacting protein PARI. Mol Cell 2012; 45: 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courseaux A, Nahon JL. Birth of two chimeric genes in the Hominidae lineage. Science 2001; 291: 1293–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes BE, Kil E, Green B, O'Neill K, Fried S, Graziano MP. The melanin-concentrating hormone receptor couples to multiple G proteins to activate diverse intracellular signalling pathways. Endocrinology 2000; 141: 4524–4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle AN, Mild G, Schlumberger SE, Drozdz R, Hintermann E, Zumsteg U. Expression and characterization of melanin-concentrating hormone receptors on mammalian cell lines. Peptides 2004; 25: 1585–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta-Grand N, Rovère C, Guyon A, Cervantes A, Brau F, Nahon JL. Melanin-concentrating hormone induces neurite outgrowth in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells through p53 and MAPKinase signaling pathways. Peptides 2009; 30: 2014–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conductier G, Brau F, Viola A, Langlet F, Ramkumar N, Dehouck B et al. Melanin-concentrating hormone regulates beat frequency of ependymal cilia and ventricular volume. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16: 845–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conductier G, Martin AO, Risold PY, Jego S, Lavoie R, Lafont C et al. Control of ventricular ciliary beating by the melanin concentrating hormone-expressing neurons of the lateral hypothalamus: a functional imaging survey. Front Endocrinol 2013; 4: 182## [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee MJ, Pissios P, Prasad D, Maratos-Flier E. Expression of melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 2 protects against diet-induced obesity in male mice. Endocrinology 2014; 155: 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A. Recent progress in the discovery of melanin-concentrating hormone 1-receptor antagonists. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2011; 21: 905–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]