Abstract

Overfeeding high-fat (HF) meals results in both short-term and long-term effects that vary depending upon adiposity status (obese vs nonobese) and family history of type 2 diabetes. Although more than 4 weeks of overeating produces mild insulin resistance, whether the same is true of a single, HF meal is not clear. We reviewed overfeeding studies of 4–8 weeks duration, studies of single HF meals and our own (unpublished) plasma insulin and glucose concentration data from 59 nonobese and 15 overweight/obese volunteers who consumed either a normal-fat (NF) breakfast or a breakfast matched for carbohydrate and protein, but with an additional 80 g of monounsaturated fat (HF). Four to eight weeks of overfeeding a HF diet causes an ∼10% reduction in insulin sensitivity. Some authors report that a single HF meal is associated with greater postprandial insulin concentrations, whereas other investigators have not confirmed such a response. We found that plasma glucose concentrations peaked later following a HF breakfast than a NF breakfast in both obese and nonobese adults and that daytime plasma insulin concentrations were not uniformly increased following a HF breakfast. We conclude that a single HF meal delays the postprandial peak in glucose concentrations, likely due to delayed gastric emptying. This will confound attempts to use insulinemia as a marker of insulin resistance. After 4–8 weeks of overeating a HF diet accompanied by 2–4 kg of fat gain, insulin sensitivity decreases by ∼10%. Although we could not demonstrate that baseline insulin resistance predicts visceral fat gain with overfeeding, normal-weight relatives of type 2 diabetes mellitus do tend to gain more weight and become more insulin resistant than those without a positive family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In summary, short-term weight gain from HF diets induces relatively mild metabolic disorders.

Keywords: insulin resistance, body fat, plasma glucose

Introduction

There is little debate that consuming high-fat (HF), high-calorie foods over long periods of time can cause weight gain and obesity, especially in the context of a sedentary lifestyle. Obesity often results in insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and is associated with inflammation, both in adipose tissue and systemically. However, the degree to which these adverse outcomes develop with shorter-term overeating is not as clear. As insulin resistance is the most commonly observed phenomenon associated with these adverse consequences, we will focus more so on this aspect of shorter-term overconsumption of HF meals.

What is insulin resistance?

Whereas there are clear and generally accepted measures of hypertension, adverse lipoprotein metabolism and liver fat content (albeit with varying degrees of sophistication), there are numerous inflammatory markers and insulin resistance measures that may provide conflicting information. For example, inflammation is variably assessed using serum markers (C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6), circulating cell populations (inflammatory leukocytes) or tissue infiltration by macrophages, lymphocytes and eosinophils. Most of the approaches to measure insulin sensitivity in humans are focused on insulin's ability to regulate glucose metabolism—suppress endogenous glucose production and stimulate glucose uptake into cells for oxidation and storage. An overview of the various approaches to characterize insulin sensitivity, along with the advantages and disadvantages of each method, are provided in Table 1. Insulin resistance with respect to glucose metabolism can be inferred using fasting glucose and insulin, either as ‘raw' or derived variables, oral glucose/meal tolerance tests, intravenous glucose tolerance tests and euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp techniques. As insulin has effects on lipid and protein metabolism (Table 2), indices of insulin-regulated FFA1 and amino-acid metabolism2 have been proposed.

Table 1. Insulin action measurements.

| Measure | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting insulin | Simple, inexpensive | May fall or rise with short-term changes in energy balance that do not reflect true changes in insulin action (for example, changes in glycemia); relatively weak correlation with more robust measures of insulin action |

| QUICKI, HOMA-IR | Simple, inexpensive, accounts for changes in fasting glucose | Imperfect reflection of changes in energy balance; relatively weak prediction (R2 ∼0.38) of insulin action as measured by insulin clamp |

| AUC insulin responses to single or multiple meals | Better reflection of the insulin response needed to control exogenous and endogenous nutrient metabolism in ‘real life' setting | Unknown correlation with other measures of insulin action; can be influenced by factors such as gastric emptying |

| Insulin modified IVGTT measure of insulin sensitivity (Si) | Better correlation with insulin clamp measures than QUICKI or HOMA-IR; can also gather insulin secretion data; simpler to do that an insulin clamp; software for analysis readily available | Cannot distinguish hepatic vs peripheral insulin resistance; mainly a measure of insulin regulation of glucose metabolism |

| Euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp (one or multiple steps) | More reproducible than other measures; considered gold standard for measuring insulin-mediated glucose disposal (mainly muscle) and suppression of endogenous glucose production; can be modified to assess FFA and amino-acid metabolism | Requires considerable training and experience; more expensive; more time consuming than IVGTT; requires expertise in isotopically labeled glucose infusions |

| Triple tracer meal technique | Distinguishes insulin effects on both liver and muscle under physiological conditions of changing glucose concentrations; technically easier to perform than an insulin clamp | Very expensive (multiple isotopes); time consuming laboratory analysis; dependent upon mathematical modeling that is not widely available |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index.

Table 2. Insulin effects on intermediary metabolism.

| Glucose | Lipid | Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulate glucose uptake | Inhibit adipose tissue lipolysis (FFA and glycerol release) | Inhibit protein breakdown (amino-acid release) |

| Inhibit endogenous glucose release | Inhibit VLDL-triglyceride release | |

| Stimulate glucose oxidation/inhibit fatty acid oxidation |

To the extent that carbohydrate intake temporarily decreases below carbohydrate oxidation, fasting plasma insulin concentrations will fall. This fall allows hepatic glucose release from glycogenolysis to proceed, together with mobilization of FFA/glycerol from adipose tissue and gluconeogenic amino acids from lean tissue to support gluconeogenesis. As a result, if insulin sensitivity is assessed using fasting plasma glucose/insulin parameters under circumstances of short-term carbohydrate imbalance, it is possible to be misled about whether insulin sensitivity has changed. Similarly, oral and intravenous insulin/glucose challenges may not completely reflect the complexity of metabolic responses if the measured parameters are not comprehensive.

For example, muscle and hepatic glycogen stores are not infinitely expandable, and resting energy expenditure is only modestly responsive to overconsumption of carbohydrate. Thus, ingesting large amounts of carbohydrate will eventually ‘fill' glycogen storage capacity, resulting in negative feedback toward insulin-mediated nonoxidative glucose disposal (a significant component of insulin action). In contrast, ‘true' insulin resistance with regard to glucose metabolism can be induced by overfeeding with fat. This may be due to alterations in mitochondrial energy metabolism3 or unhealthy increases in intracellular diacylglycerols4 and ceramides,5, 6 molecules that impair insulin signaling. Unfortunately, less is known about the cellular mechanisms that lead to insulin resistance in adipose tissue (reduced ability of insulin to suppress FFA release) or lean tissue (reduced ability of insulin to suppress proteolysis/amino-acid release).

We examined the studies that use shorter-term overfeeding/weight gain paradigms to assess how readily ‘insulin resistance' can be induced with fat gain. In addition, we reviewed the literature to better understand whether and how single, HF meals can alter the metabolic milieu. Finally, we reexamined unpublished data from some of our HF meal studies7, 8 to assess whether we could detect significant adverse effects from a single high monounsaturated fat (MUFA) meal on subsequent glycemia/insulinemia.

Effects of HF feeding that result in weight gain

Two recent studies report that 4–8 weeks of overeating a HF diet, accompanied by 1–4 kg of fat gain, can reduce insulin sensitivity by ∼10%.9, 10, 11 Tam et al.9 and Samocha–Bonet et al.10 used the euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp technique to measure changes in insulin action in 36 healthy adults overfed for 28 days. Votruba and Jensen11 used a 24-h insulin profile and an intravenous glucose tolerance test to measure changes in insulin action in 28 healthy, normal-weight volunteers overfed for 8 weeks. Similar findings of inducing mild insulin resistance have been reported with shorter (3 days)12 and longer overfeeding intervals (4.5 months).13 Although chronic low-level inflammation has been implicated as a primary factor in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes,14 Tam et al.9 found that 28 days of overfeeding healthy adults with a HF diet resulted in moderate weight gain (2–4 kg), significant increases in total and abdominal fat mass, liver fat deposition, increases in fasting insulin and an ∼10% decrease in insulin sensitivity by hyperinsulinemic clamp. However, peripheral insulin resistance occurred without substantial changes in circulating inflammatory markers or increases in inflammatory cells within subcutaneous adipose tissue.9 Greater reductions in insulin sensitivity and increases in adipose tissue macrophage-specific markers (F4/80 or CD68) may occur with 8 weeks of a HF diet in mice15 and 16 weeks of a HF diet16 in humans. Combined, these findings indicate that mild, weight gain-induced insulin resistance from short-term overfeeding is an early metabolic defect that precedes immune activation and macrophage recruitment into subcutaneous adipose tissue in humans.

One potential explanation for the relatively mild impairment in insulin action with fat gain is the ability of adipocytes to enlarge (abdominal) or proliferate (leg) to safely accommodate extra fat.17 Provided adipose tissue fatty acid release is normally regulated, which appears to be the case with modest fat gain,10 lean tissue may be protected to a point from overeating.

It is well known that first-degree relatives of individuals with a family history of type 2 diabetes are at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.18 Following a 28-day HF overfeeding protocol in which participants were free-living and self-selecting their foods, normal-weight relatives with a family history of type 2 diabetes gained more weight and became more insulin resistant than those without a positive family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus.10 In addition, a trend toward greater fat and energy consumption was observed in individuals with a family history of type 2 diabetes as compared with those without a family history of type 2 diabetes.10 We evaluated the possibility that those individuals who were more insulin resistant before weight gain would gain a greater portion of fat in the upper body/visceral depots with overfeeding—there was no indication that variations in insulin action in nonobese adults is related to the tendency to gain visceral fat in the short term.11

Effects of single, HF meals on insulin sensitivity

Some authors report that consuming even a single HF meal may result in insulin resistance,19 possibly related to the type of dietary fatty acid.20 However, it has also been reported that the addition of fat to a pure carbohydrate meal reduces total postprandial glycemia in nondiabetic adults, presumably due to effects of fat on gastric emptying.21 Less of an effect on glucose/insulin is seen in persons with type 2 diabetes subjected to a similar experimental paradigm.22

Not all glucose/insulin responses are able to be interpreted in isolation. For example, Gannon et al.21 found a lesser plasma glucose response to a meal consisting of carbohydrate and fat (potato plus butter) than potato alone while the postprandial insulin response was nearly identical. Although an easy interpretation might be that dietary fat induced insulin resistance, their finding that plasma glucagon concentrations were substantially greater after the potato/butter meal offers an alternative explanation. Glucose counter-regulatory responses likely preserved plasma glucose concentrations in the face of excess insulin for the prevailing conditions.

Ercan et al.19 and Robertson et al.20 assessed the insulin response to second meals (those consumed after the HF or normal-fat (NF) meals), and only following the consumption of a meal high in saturated fatty acids was there evidence of a greater insulin requirement to maintain subsequent glucose homeostasis.20 Unfortunately, studies using insulin clamp techniques or meal triple tracer approaches23 to assess the regulation of glucose, FFA and protein metabolism following a HF meal have not been undertaken.

We have examined the effects of a high-MUFA load on meal fatty acid metabolism (oxidation, storage in adipose tissue).7, 8 Because we also measured the daytime plasma glucose and insulin and glucose responses, we had the opportunity to examine whether MUFA added to a mixed meal creates subsequent hyperinsulinemia/hyperglycemia.

High-MUFA mixed meal vs NF mixed meal

Volunteers

These results are from volunteers with complete data who participated in two previously published studies conducted at Mayo Clinic.7, 8 The details of the protocol were included in those publications. Volunteers were randomly assigned to receive either a HF or NF breakfast. The glucose and insulin data presented herein were collected as part of the study described in Votruba and Jensen;8 we analyzed date from a subset of eight nonobese (two with a HF meal) and seven obese (four with a HF meal) volunteers with complete insulin and glucose data.

Protocol

Volunteers were fed at the Clinical Research Unit (CRU) of the Mayo CTSA metabolic kitchen for 3 days before the study to ensure weight stability and constant macronutrient (50% carbohydrate, 35% fat and 15% protein) intake as previously described.24, 25

Following the dietary control period, volunteers were admitted to CRU at 1700 hours, given a meal at 1800 hours and were not allowed to eat again until the test meal next morning. An intravenous catheter was placed into a dorsal hand vein in a retrograde manner and used for blood sampling using the heated-box technique. Baseline blood samples were obtained at 0745 hours the next morning, and at 0800 hours volunteers were given the test meal. This liquid meal (Ensure Plus, Ross Laboratories, Columbus, OH, USA) provided calories equaling either 40% of their resting energy expenditure as determined by indirect calorimetry (NF breakfast) or 40% of resting energy expenditure plus an additional 80 g of triolein (Karlshams, Karlsham, Sweden) (HF breakfast). Each volunteer received normal (solid food) meals at 1200 and 1800 hours that were consistent with their meal patterns for the previous 3 days. Blood samples were taken hourly until 1600 hours and then less frequently until 0800 hours the following morning.

Assays

A Beckman glucose analyzer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA) was used to measure plasma glucose concentration. Plasma insulin concentration was measured using a chemiluminescence method with the Access Ultrasensitive Immunoenzymatic assay system (Beckman, Chaska, MN, USA).

Statistical analysis

Plasma insulin concentrations were log-transformed to normalize the data distribution before statistical testing. Nonpaired t-tests were used to compare the groups consuming the HF vs NF breakfasts. A P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant, except for when comparing plasma insulin and glucose concentrations over the 24-h interval, in which case a P value⩽0.01 was used to partially account for multiple testing. JMP (version 7.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the analysis.

Statement of ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research. Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Volunteer characteristics

The mean age of the nonobese (31±9 years) and 20 obese volunteers (35±7 years) was not significantly different. The body mass index was 22.9±1.7 and 36.1±4.7 kg m−2 for the nonobese and obese volunteers, respectively. Volunteers were randomly assigned to the NF (34 nonobese, 8 obese) or HF (25 nonobese, 7 obese) breakfast groups. Baseline plasma insulin was fourfold greater (P<0.005) in the obese groups than in nonobese groups, but fasting plasma glucose concentrations were similar (data not shown).

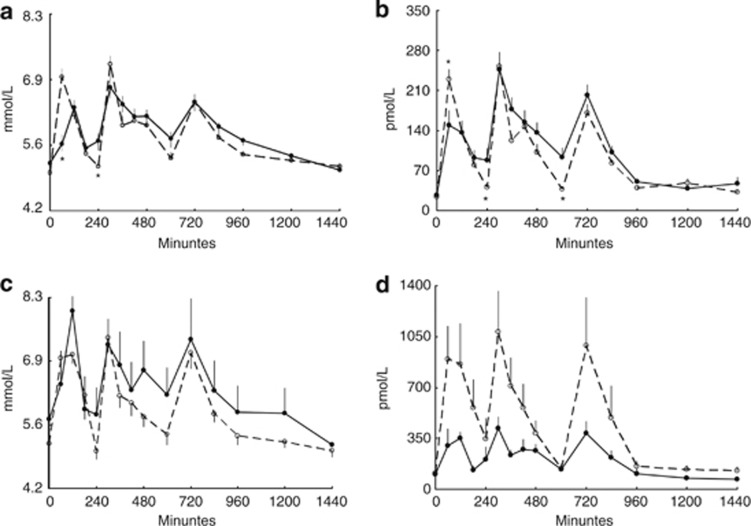

Plasma glucose concentration

Following NF breakfast, plasma glucose concentrations peaked at 60 min in both nonobese and obese volunteers. In contrast, after a HF breakfast, peak glucose concentrations occurred at 120 min in both groups (Figures 1a and c). The 60-min plasma glucose concentration was less following the HF (5.6±0.8 mmol l−1) than NF (7.1±1.1 mmol l−1) breakfast in nonobese volunteers (P<0.0001). For all volunteers given a NF breakfast, plasma glucose concentration peaked at 60 min in 68%, whereas following a HF breakfast, peak plasma glucose was at 120 min in 75% subjects (P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Plasma glucose (a and c) and insulin concentrations (b and d) over 24 h following a NF (dashed line) and HF (bold line) breakfast. Data for nonobese volunteers are provided in panels a and b; data for obese volunteers are provided in panels c and d. Breakfast was given at 0 h, lunch at 4 h and supper at 10 h. *Significantly different from HF breakfast meal; P<0.01.

Plasma insulin concentration

Plasma insulin concentrations are depicted in Figures 1b and d. In nonobese participants consuming HF breakfast, plasma insulin concentrations at 1 h following breakfast were less (P=0.01) than those in the NF breakfast group, as might be expected given the lower plasma glucose concentrations. However, the nonobese volunteers given the NF breakfast then had lower (P<0.05) insulin concentrations at 4 and 10 h after breakfast compared with those given HF breakfast, coinciding with slightly greater plasma glucose concentrations in those given the HF breakfast.

For obese volunteers, peak insulin was observed 1 h after a NF breakfast and 2 h after a HF breakfast. Plasma insulin concentrations were not statistically significantly different in the two obese groups throughout the day. Thus, glycemic status was maintained without a significant increase in daytime insulinemia.

Discussion

Although there are potential short-term adverse effects of HF meals, with the exception of exaggerated postprandial chylomicronemia, such effects are not universally reported. We found that a single, high-MUFA meal does not generate remarkable insulin resistance in nonobese or obese adults as measured by the insulinemia required to maintain glucose homeostasis throughout the subsequent day.

We found that the daytime glucose and insulin response to a breakfast meal with the same amount of carbohydrate and protein, but much greater MUFA content, was a delay in the rise in plasma glucose concentration in both nonobese and obese adults. This is most likely because of the delay in gastric emptying caused by dietary fat, which has been well documented.26 Differential stimulation of gut hormones, such as gastric inhibitory polypeptide and cholecystokinin, by dietary fat may also influence insulin secretion.27

In summary, careful consideration of the type of measures to take to understand the short- and long-term effects of overfeeding with a HF meal or diet are crucial. If insulin action with respect to glucose metabolism is to be measured, is hepatic or muscle of greatest interest? Is adipose tissue insulin resistance (lipolysis) or protein metabolism (proteolysis) important? Surrogate measures may be useful if large numbers of subjects can be studied, but more direct measures will be needed to detect small changes or if only limited numbers of subjects can be studied. Up to 8 weeks of overfeeding accompanied by 1–4 kg of fat gain induces little in the way of inflammation or insulin resistance, although relatives of those predisposed to type 2 diabetes mellitus may be a special case.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants in this study, as well as Carol Siverling, RN, Deborah Harteneck, Darlene Lucas, Jessica Eastman, the staff of Mayo CRU and Monica Davis, for their editorial assistance. This work was supported by Grants DK45343, DK50456 (Minnesota Obesity Center), and RR-0585 from the US Public Health Service and by the Mayo Foundation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article was published as part of a supplement funded with an unrestricted educational contribution from Desjardins Sécurité Financière.

References

- Jensen MD, Nielsen S. Insulin dose response analysis of free fatty acid kinetics. Metabolism 2007; 56: 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellino P, Luzi L, Simonson DC, Haymond M, DeFronzo RA. Effect of insulin and plasma amino acid concentrations on leucine metabolism in man. Role of substrate availability on estimates of whole body protein synthesis. J Clin Invest 1987; 80: 1784–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin C-T et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 573–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KS, Heydrick S, kurowski T, Ruderman NB. Diacylglycerol-protein kinase C signalling in skeletal muscle: a possible link to insulin resistance. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1991; 104: 206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduch E, Balendran A, Batty IH, Litherland GJ, Blair AS, Downes CP et al. Ceramide impairs the insulin-dependent membrane recruitment of protein kinase B leading to a loss in downstream signalling in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Diabetologia 2001; 44: 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford S, Hoehn KL, Liu F, Summers SA. Regulation of insulin action by ceramide: dual mechanisms linking ceramide accumulation to the inhibition of Akt/protein kinase B. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 36608–36615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votruba SB, Mattison RS, Dumesic DA, Koutsari C, Jensen MD. Meal fatty acid uptake in visceral fat in women. Diabetes 2007; 56: 2589–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votruba SB, Jensen MD. Sex-specific differences in leg fat uptake are revealed with a high-fat meal. Am J Physiol 2006; 291: E1115–E1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam CS, Viardot A, Clement K, Tordjman J, Tonks K, Greenfield JR et al. Short-term overfeeding may induce peripheral insulin resistance without altering subcutaneous adipose tissue macrophages in humans. Diabetes 2010; 59: 2164–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samocha-Bonet D, Campbell LV, Viardot A, Freund J, Tam CS, Greenfield JR et al. A family history of type 2 diabetes increases risk factors associated with overfeeding. Diabetologia 2010; 53: 1700–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votruba SB, Jensen MD. Insulin sensitivity and regional fat gain in response to overfeeding. Obesity 2011; 19: 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann OP, Dahl DB, Brechtel K, Machann J, Haap M, Maier T et al. Effects of intravenous and dietary lipid challenge on intramyocellular lipid content and the relation with insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes 2001; 50: 2579–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann J, Kallabis B, Oppel U, Sypchenko O, Wagenpfeil S, Schusdziarra V. Development of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance during the early stage of weight gain. Am J Physiol 2008; 294: E568–E575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993; 259: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strissel KJ, DeFuria J, Shaul ME, Bennett G, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. T-cell recruitment and Th1 polarization in adipose tissue during diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6 mice. Obesity 2010; 18: 1918–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 1821–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchoukalova Y, Votruba SB, Tchkonia T, Giorgadze N, Kirkland JL, Jensen MD. Regional differences in cellular mechanisms of adipose tissue gain with overfeeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 18226–18231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs JB, D'Agostino RBS, Wilson PWF, Cupples LA, Nathan DM, Singer DE. Risk variable clustering in the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes 1997; 46: 1594–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan N, Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. Effect of added fat on the plasma glucose and insulin response to ingested potato given in various combinations as two meals in normal individuals. Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 1453–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MD, Jackson KG, Fielding BA, Williams CM, Frayn KN. Acute effects of meal fatty acid composition on insulin sensitivity in healthy post-menopausal women. Br J Nutr 2002; 88: 635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ, Westphal SA, Seaquist ER. The effect of fat and carbohydrate on plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and triglycerides in normal male subjects. J Am Coll Nutr 1993; 12: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon MC, Ercan N, Westphal SA, Nuttall FQ. Effect of added fat on plasma glucose and insulin response to ingested potato in individuals with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1993; 16: 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Man C, Campioni M, Polonsky KS, Basu R, Rizza RA, Toffolo G et al. Two-hour seven-sample oral glucose tolerance test and meal protocol: minimal model assessment of beta-cell responsivity and insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes 2005; 54: 3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanski SA, Nelson RM, Jensen MD. Meal fatty acid uptake in human adipose tissue: technical and experimental design issues. Am J Physiol 2000; 279: E447–E454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uranga AP, Levine J, Jensen M. Isotope tracer measures of meal fatty acid metabolism: reproducibility and effects of the menstrual cycle. Am J Physiol 2005; 288: E547–E555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilcore D, Chaikomin R, Jones KL, Russo A, Feinle-Bisset C, Wishart JM et al. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91: 2062–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinle C, O'Donovan D, Doran S, Andrews JM, Wishart J, Chapman I et al. Effects of fat digestion on appetite, APD motility, and gut hormones in response to duodenal fat infusion in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003; 284: G798–G807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]