Abstract

Understanding the non-sensory components of the pain experience is crucial to developing effective treatments for pain conditions. Chronic pain is associated with increased incidence of anxio-depressive disorders, and patients often report feelings of vulnerability which can decrease quality of life. In animal models of pain, observation of behaviours such as thigmotaxis can be used to detect such affective disturbances by exploiting the influence of nociceptive stimuli on the innate behavioural conflict between exploration of a novel space and predator avoidance behaviour. This study investigates whether acute and repeated bladder inflammation in adult female Wistar rats increases thigmotactic behaviour in the open field paradigm, and aims to determine whether this correlates with activation in the central amygdala, as measured by c-Fos immunoreactivity. Additionally, up-regulation of inflammatory mediators in the urinary bladder was measured using RT-qPCR array featuring 92 transcripts to examine how local mediators change under experimental conditions. We found acute but not repeated turpentine inflammation of the bladder increased thigmotactic behaviour (decreased frequency of entry to the inner zone) in the open field paradigm, a result that was also observed in the catheter-only instrumentation group. Decreases in locomotor activity were also observed in both models in turpentine and instrumentation groups. No differences were observed in c-Fos activation, although a general increased in activation along the rostro-caudal axis was seen. Inflammatory mediator up-regulation was greatest following acute inflammation, with CCL12, CCL7, and IL-1β significantly up-regulated in both conditions when compared to naïve tissue. These results suggest that acute catheterisation, with or without turpentine inflammation, induces affective alterations detectable in the open field paradigm accompanied by up-regulation of multiple inflammatory mediators.

Keywords: Pain, Inflammation, Open Field, Cytokines, Amygdala, Behaviour, c-Fos

1. Introduction

Pain is a complex experience, dependent on the interplay between sensory aspects and centrally-mediated affective, motivational, cognitive, and behavioural elements. The current translational difficulties in developing effective pain relief are associated in part with a pre-clinical focus on positive sensory signs, whereas the clinical burden of chronic pain comes largely from negative behavioural responses, such as avoiding behaviours perceived as exacerbating, and a general decrease in quality of life as a result of unpredictable spontaneous pain ( Hummel et al., 2008; Suskind et al., 2013). This study uses an animal model to increase our understanding of the non-sensory components of pain by investigating whether acute and repeated visceral inflammation influence behaviour, if alterations are associated with activational changes in central brain areas implicated in generation of affective behavioural responses, and investigate the local changes in cytokine levels twenty-four hours after inflammation.

Visceral pain affects 16–25% of the general population ( Collett, 2013), and is experienced by virtually all at some point, if only transiently. Despite this, visceral pain is inherently difficult to study in animal models, due to sparse innervation and referred pain complicating precise location of origin. This is reflected in the literature. A PubMed search conducted on the 22 nd June 2014 (search terms: (pain) AND (neuropathic) vs. (pain) AND (visceral)) revealed 12,938 results for pain with a neuropathic element, compared to 5035 for pain with a visceral component. Of these, 510 neuropathic studies were conducted in vivo, compared to only 40 for visceral (additional search term: AND ( in vivo)). None of these in vivo visceral pain publications involved the open field paradigm (additional search paradigm: AND (open field)), which was one of the key reasons for this study. We chose the turpentine model of visceral inflammation due to its simplicity of induction and demonstrated phenotype of viscero-visceral hyper-reflexia and referred hyperalgesia ( Jaggar et al., 1999), that is reversible with analgesics ( Farquhar-Smith & Rice, 2001; Jaggar et al., 1998; Rice, 1995).

To detect negative behavioural responses in animals, complex behavioural outcomes are commonly used. Thigmotaxis is a behaviour characterised by a preference for movement along a surface (i.e. “wall-hugging”), which shows an inverse relationship with exploration of novel areas in rats. It is hypothesised as related to risk assessment and predator avoidance, with the presence of spontaneous or ongoing pain decreasing potentially risky behaviours, such as exploration. The open field paradigm is capable of detecting these subtle behavioural differences in experimental models of pain with varying aetiologies including antiretroviral therapy-induced neuropathy ( Huang et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2008), chemotherapy-induced neuropathy ( Barzegar-Fallah et al., 2014), spinal nerve transection ( Blackbeard et al., 2012), spinal nerve ligation ( Ewan & Martin 2014; Kontinen et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 2007), chronic constriction injury ( Grégoire et al., 2012), and post-traumatic peripheral nerve trauma ( Medico et al., 2004).

Pain acts on multiple levels within the nervous system: sensory signals from the periphery are received centrally and interpreted in relation to previous experience and current circumstances to produce a behavioural response. The different subdivisions of the amygdala receive sensory input from areas such as the thalamus and spinal cord (capsulo-lateral portion of the central amygdala, via the lateral and basolateral amygdalae), and provides output via the medial nucleus of the central amygdala to the pre-frontal cortex and hypothalamus. This pattern of connectivity suggests involvement in the assessment and generation of emotional associations that form an integral part of the pain experience ( Neugebauer et al., 2009). Studies have shown pain-associated increases in amygdala activity both clinically and pre-clinically in pancreatitis ( Frøkjær et al., 2011), cluster headache ( Seifert et al., 2011), back pain, arthritis ( Baliki et al., 2008), fibromyalgia ( Harris et al., 2009), and menstrual pain ( Tu et al., 2010). In this study, we look at c-Fos immunoreactivity (a marker of persistent neural activation; Barth, 2007) in the amygdala with respect to open field activity, considering whether the presence of acute or persistent visceral inflammation influences c-Fos expression.

Cytokines and associated inflammatory mediators are up-regulated in pain conditions with an inflammatory component ( Calvo et al., 2012; Cheppudira et al., 2009; Girard et al., 2011; Johansson et al., 2003; Nowak et al., 2012; Quan-Xin et al., 2012; Skurlova et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). In particular, Dawes and co-workers demonstrated commonality between cytokines up-regulated following UVB-irradiation in clinical and pre-clinical models, showing the pro-inflammatory cytokine CXCL5 is up-regulated and capable of producing hypersensitivity in otherwise naïve rats ( Dawes et al., 2011). In this study, we hope to show the profile of inflammatory mediators up-regulated following bladder inflammation and investigate whether this profile changes with repeated inflammation.

This study aims to investigate the acute and medium-term effects of visceral inflammation on thigmotactic behaviour, correlating differences in behaviour with both central activation (c-Fos immunoreactivity in the amygdala), and peripheral levels of inflammatory cytokines to further understand the behavioural implications of visceral inflammation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Ethical statement

All animal experiments conformed to British Home Office Regulations (Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012 (SI 2012/3039) and were performed under the authority of United Kingdom Home Office Project Licence 70/7162, adhering to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) guidelines for in vivo research ( Zimmermann, 1983; and http://www.iasp-pain.org). Experiments were designed according to Good Laboratory Practice standards ( Macleod et al., 2009) and reported in accordance with the ARRIVE Guidelines ( Kilkenny et al., 2010; Rice et al., 2013). Table 1 shows the major domains of good laboratory practice followed.

Table 1. Major Domains of Good Laboratory Practice (after Macleod et al., 2009).

| Characteristic | Description of procedures |

|---|---|

| Sample size calculation | Group size was determined by sample size estimation for each experiment by SigmaStat

software, version 3.5 (ANOVA sample size, desired power = 0.8, α = 0.05). Effect sizes for estimation were derived from previous studies in our group. |

| Inclusion and exclusion

criteria |

Animals which died prior to/during model induction were excluded from further study.

There were no exclusion criteria for the open field study; animals were excluded from c-Fos analysis if >90min elapsed between open field and perfusion, or if sections were badly damaged. |

| Randomization | Animals were randomised to model group (naïve, VC, TC) by cage using a

pseudorandom ABCBCACAB labelling system. |

| Allocation concealment | The person creating the model (i.e. instillation of turpentine or olive oil) was theoretically

unaware of the allocation to treatment group, but due to the pungent odour of turpentine, this was difficult to maintain. Procedures were still followed. This was achieved by the blinding procedure described below, as well as masking cage labels or turning around the cages before each behavioural assessment session. |

| Reporting of animals

excluded from analysis |

All animals excluded are reported in Figure 1. |

| Blinded measurement,

assessment, and analysis of outcome |

Codes were assigned to different treatments by an independent person and kept in a

sealed envelope. The codes were not broken until the analysis had been completed. The experimenter was blinded to the experimental group to which an animal was randomized. In addition, open field videos were renamed by an independent person before analysing, and immunohistochemistry sections were identified by animal not group code. |

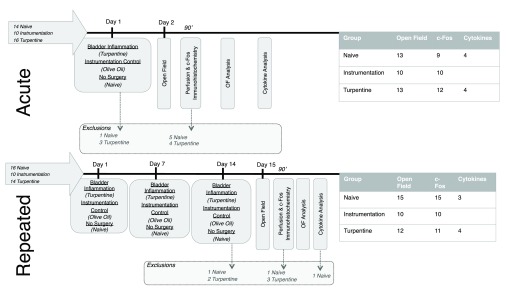

Figure 1. Experimental design for both acute and repeated models.

The arrows on the right show the total number of animals used, with exclusions at each timepoint and final group sizes indicated in the central and right of the diagram respectively. Animals were lost during surgery due to complications associated with anaesthesia, and excluded from immunohistochemical analysis if hemispheric differentiation was not possible.

2.2 Experimental animals

Female Wistar rats (Charles River, UK, RRID:RGD_737929), weighing 180–200 g on arrival, were housed in groups of 3–4 in individually ventilated cages with free access to food (RM1 (P), Special Diet Services, UK) and tap water. Animals were maintained under a 12 hour light cycle (07:00–19:00) in temperature and humidity-controlled conditions (25°C, 30%, both ± 5). Cages were cleaned weekly on a Tuesday (p.m.), and housed in a room containing mice and rats of both sexes. Animals were habituated to the holding room for a minimum 48 hours after delivery from the main campus facilities.

2.3 Study design

Sample size calculations used data from studies looking at the effect of neuropathic injury (spinal nerve transection) on frequency of inner zone entry in the open field ( Morland et al., 2015 manuscript in preparation). Using a power (1-β) of 0.08 and alpha (α) value of 0.05, a sample size of 8 was calculated as sufficient to detect alterations in thigmotaxis.

There were three experimental groups: naïve, instrumentation (anaesthesia with catheterization and instillation of 0.5ml 100% olive oil), and turpentine (anaesthesia with catheterization, and inhalation anesthetic instillation of 0.5ml 50% turpentine). Full details of group sizes and exclusions are given in Figure 1. Female animals were selected for ease of catheterization.

All behavioural experiments were conducted during the light phase (09:00–18:00) in a dedicated behavioural laboratory, with surgical procedures carried out in a separate but adjacent surgical room. In vivo studies were conducted in batches of 2–3 animals per group (n=6–9/batch) due to capacity and protocol constraints. Each animal was treated as a single experimental unit, with immunohistochemical analysis conducted using average values from a number of sequential sections from a single animal, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Average number of sections analysed per animal during immunohistochemical analysis.

| Mean | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | Naïve | 5.10 | 4 | 7 |

| Instrumentation | 4.88 | 4 | 7 | |

| Turpentine | 4.46 | 3 | 6 | |

| Repeated | Naïve | 2.87 | 1 | 5 |

| Instrumentation | 3.90 | 2 | 6 | |

| Turpentine | 3.83 | 1 | 7 |

2.4 Model induction

Under isoflurane anaesthesia, (1.5–3% in 2 L/min O 2), bladder inflammation was induced as described by McMahon & Abel (1987). Briefly, a transurethral catheter (⌀ 1.02mm; Portex, UK) was introduced into the bladder, and position verified by applying gentle abdominal pressure to empty the bladder, before instillation of 0.5 ml olive oil or turpentine (50% in olive oil). The instillation was maintained under anaesthesia for 2 hours before removal of the catheter. The animal was allowed to recover in a separate area before returning to the home cage.

Based on the above protocol, a model of persistent bladder inflammation was developed, involving three instillations, each one week apart. For both studies, surgery was conducted during the light phase and timed to ensure exactly 24 hours between instillation and exposure to the open field.

2.5 Cytokine activation

Tissue from whole bladders snap frozen during the saline phase of perfusion was used for RNA extraction. Briefly, samples were homogenized and total RNA obtained using a “hybrid” method of phenol extraction (Trizol, Invitrogen, USA) and column purification (RNeasy, Qiagen, USA). All samples were deoxyribonuclease (DNase, Qiagen, USA) treated to avoid genomic contamination. Purity and integrity confirmed with an RNA 6000 Nano Chip (Agilent, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from RNA using a SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, USA).

Custom-made Taqman array cards (as described by Dawes et al., 2011), featuring four sets of 92 different primer pairs, and four house-keeping genes: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 18S ribosomal protein, β-actin, and β2-microtubulin. Inflammatory mediators were categorized into cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, enzymes, and ‘other’ ( Table S1). Each cDNA sample was diluted with PCR-grade water and added in a 1:1 ratio to Taqman Universal master mix to produce a final concentration of 1 ng/µl cDNA. Samples were loaded into the appropriate ports (1 µl/well) according to manufacturer guidelines. Cards were placed into a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA), and subjected to 40 cycles of amplification. Transcript expression was measured with the ΔΔ C t (cycling time) method normalised to the geometric mean of the four housekeeping genes using the R package NormqPCR ( https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/qpcr/). Relative changes in transcript levels are presented as fold change (FC). When transcript numbers were undetermined for a given detector in <50% of samples, the average C t value was calculated with the remaining data values. If transcript numbers were undetermined in >50% of transcripts for a given sample, a default C t of 38 was assigned. If these conditions coincided, no FC value was calculated. Difference in gene expression were detected using the significance analysis of microarray (SAM) technique, involving calculation of false discovery rates (FDR), represented as a q statistic ( Lin et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2002).

2.6 Thigmotaxis in the open field

Humidity and temperature were maintained at 25°C and 30% humidity respectively. Light levels outside the isolation chamber during open field paradigms ranged from 70–300 lux. As rodents have a greater auditory range than humans, ultrasonic sound recordings were taken using a Mini-3 Bat Detector (Ultra Sound Advice, UK) to determine the background levels of high frequency sound generated by equipment. Fluorescent lighting and computer equipment emitted signals within the 20–50 kHz range - this equipment was switched on for the duration of each experiment and animals were allowed to acclimatise to the testing room for 30 min prior to testing.

Thigmotaxis. The open field paradigm was used to assess thigmotaxis. The open field arena (black, 100 cm 2) was enclosed in an isolation chamber (115 × 115 × 255 cm) to minimise environmental interference. Light levels within the open field were set at 12 lux (measured in the centre of the arena). Animals were introduced into the near corner of the arena, facing the centre of the arena, and allowed to explore for 15 min. The arena was cleaned with 0.02% Distel (formerly Trigene, Tristel Solutions Ltd., UK) between trials. Behaviour was captured by high sensitivity camera (VCB 3372; Sanyo, Japan), and analysed using Ethovision XT 10.1 (Tracksys, UK (for Noldus, the Netherlands), RRID:rid_000100). The primary pre-determined outcome measure was frequency of entry into a virtual central zone (40 cm 2). Secondary outcome measures were duration in the central zone, and rearing. Total distance travelled was used as a measure of general locomotor activity. Rearing was defined as both forelimbs elevated, either against a wall, or freestanding, and measured by a trained observer watching at 4 × playback speed.

2.7 Amygdala activation

Histological studies. To capture peak c-Fos activation in response to the open field, fixation perfusion took place within 90–120min of open field exposure. Bladders were extracted and snap frozen in LN 2 during the saline phase of perfusion fixation.

Animals were humanely killed with pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with 0.9% heparinized saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 hours and cryo-protected in 30% sucrose for at least 3 days prior to sectioning (50 µm) on a freezing microtome (model no. HM450, Thermo Scientific, USA). Sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 1(NaH 2PO 4.2H 2O):9(Na 2HPO 4.12H 2O):7(NaCl) in dH 2O), quenched with 0.03% H 2O 2 (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), washed again in PBS, blocked for one hour in 5% normal goat serum (NGS, Millipore, UK; PBS with 0.3% TX (Triton X-100, BDH, UK)), before incubation overnight at 4°C with 1:20,000 polyclonal rabbit IgG anti-c-Fos (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-52 RRID:AB_2106783; 0.3% PBS-TX, 2% NGS). The following day, sections were washed in PBS and incubated for two hours at room temperature (20°C) with 1:250 Biotin-SP-conjugated Affinipure goat anti-rabbit IgG (F(ab’)2 fragment specific; Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA, Cat# 111-036-006 RRID:AB_2313586; 0.3% PBS-TX, 2% NGS). Staining was visualised using a Vectastain ABC kit (avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex, VectorLabs, UK) and DAB (3, 3′-Diaminobenzidine) with nickel salt intensification (VectorLabs, UK). Sections were mounted, counterstained with toluidine blue to enhance cyto-architecture, and cover-slipped using DePex mounting media (VWR, UK) prior to image capture.

Image quantification. The bregma position of each mounted section was determined with reference to Paxinos & Watson (6 th Edition, 2007), and only those between -1.44mm and -3.36mm (range of the central amygdala) were captured using a Leica DM R light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Image analysis was conducted using Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, USA), and the mean number of positively stained cells per mm 2 calculated for each subdivision of the central amygdala (medial, lateral, and capsular), with lateralization and rostro-caudal axis position noted. A positively stained cell was defined as having a clearly defined dark rounded nucleus (blue/black) - sections without c-Fos positive cells in areas out-with the central amygdala were excluded. Image analysis was conducted blind, using individual animal identifiers rather than group codes until completion of analysis.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Thigmotaxis was analysed using 1-way ANOVA, with Kruskal-Wallis utilised for data that was not normally distributed. c-Fos data was analysed using 1-, 2-, and 3-way ANOVA taking account of hemispheric, sub-nuclear, and rostro-caudal designations of the central amygdala. Where overall ANOVA detected significant differences, multiple comparisons procedures were used - Holm-Sidak for normally distributed data, and Dunn’s multiple comparison for non-parametric tests. Correlations were assessed using Pearson correlation coefficients. Inflammatory mediator analysis was conducted using Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM), and the false discovery method (FDR), which take into account dependence between transcripts and uses non-parametric techniques. Significance was taken as q=0%.

Summary statistics are expressed as mean (standard deviation; SD) when data was normally distributed, or median (interquartile range; IQR) when data failed normality testing. Significance was taken at p<0.05.

All statistical tests were performed, sample sizes calculated, and appropriate graphs generated using OriginPro v9.1 (OriginLab, USA) and SigmaPlot v10 (Systat Software Inc., USA; RRID:SciRes_000184).

3. Results

Dataset 1. Figshare: Cytokine q-RT-PCR, c-Fos immunoreactivity and open field behaviour data in rats following bladder inflammation. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.1394861

Exclusions

See Figure 1 for a summary of exclusions and group sizes used. Bladder inflammation as a model of visceral inflammation was generally well tolerated; the main cause of mortality was surgical complications and related anaesthesia. In the repeated model, all deaths occurred during/following the final inflammation session. Following recovery from anaesthesia and return to the home cage, animals were alert and outwardly indistinguishable.

3.1 Inflammatory mediator mRNA levels

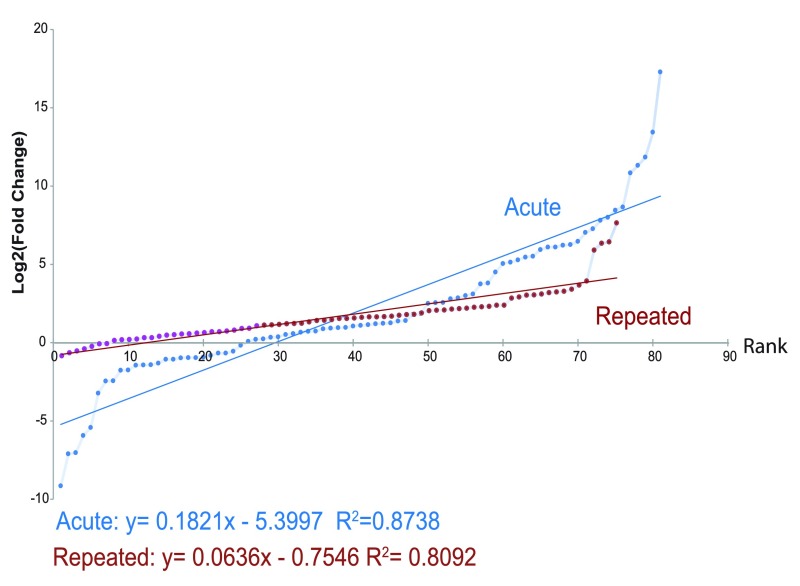

3.1.1 Acute bladder inflammation. A total of 81/92 cytokine transcripts were analysed for magnitude and significance of transcript up-regulation following acute bladder inflammation. 11 markers (CCL1, CCL28, CTLA-8, CXCL17, IFNγ, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-9, IL-13, IL-27) were excluded from the acute inflammation model due to high cycle time (>38), indicative of low levels or issues in detection. The top ten up-regulated transcripts are shown in Table 3. Figure 1 shows the rank FC for all markers analysed. Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) was used to identify 25 mRNAs that were significantly different in the turpentine group compared to naive (FC >1.5, Δ = 1.61, FDR=0%). Of these, 13 were classified as chemokines, 9 as cytokines, 2 as enzymes, 2 as growth factors, and 1 as ‘other’, as seen in Table 4.

Table 3. Top 10 up-regulated transcripts in bladder tissue from turpentine group, ranked by mRNA fold change normalised to naive values.

Data presented as mean fold change (95% confidence interval), n=3–4 animals/group.

| Acute Bladder Inflammation | Repeated Bladder Inflammation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Gene | Fold Change | 95% Confidence

Interval |

Gene | Fold Change | 95% Confidence

Interval |

| 1 | NOS2 | 159110.28 | -127366.6–445587.2 | CCL12 | 169.65 | 67.05–272.25 |

| 2 | PROK2 | 11060.01 | -12741.5–34861.5 | CTLA-8 | 75.098 | -56.21–206.4 |

| 3 | CXCL2 | 3679.32 | -4618.0–11976.7 | CXCL17 | 71.2 | -22.64–165.03 |

| 4 | CCL3 | 2541.99 | -1417.4–6501.3 | CXCL11 | 53.27 | -71.05–177.6 |

| 5 | IL-1α | 1827.32 | -2717.6–6372.2 | NOS2 | 14.2 | -9.46–37.87 |

| 6 | IL-1β | 403.78 | -328.2–1135.7 | BDNF | 11.9 | -2.06–25.86 |

| 7 | CSF3 | 350.52 | -269.9–971.0 | CXCL2 | 9.94 | -9.78–29.65 |

| 8 | CXCL3 | 254.33 | -131.8–640.5 | PROK2 | 9.12 | -10.24–28.49 |

| 9 | IL-10 | 222.75 | -399.6–845.1 | IL-21 | 8.88 | -17.20–34.96 |

| 10 | IL-6 | 153.21 | -42.8–349.3 | IL-1β | 8.63 | 4.62–12.65 |

Table 4. Significance analysis of qRT-PCR array (SAM) results for acute and repeated bladder inflammation.

Significant fold difference in acute model a, repeated model b, or both c; Significance level, FDR q=0% denoted by bold text.

| Acute | Repeated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | Score (d) | q-value(%) | FC | Score (d) | q-value (%) | ||

| Chemokines | CCL2 a | 43.47 | 4.63 | 0.00 | 3.36 | 1.43 | 8.44 |

| CCL3 a | 1656.98 | 8.89 | 0.00 | transcript excluded | |||

| CCL4 a | 95.66 | 2.55 | 0.00 | 6.74 | 1.13 | 8.44 | |

| CCL6 a | 14.34 | 2.52 | 0.00 | 3.98 | 1.90 | 5.52 | |

| CCL7 c | 17.96 | 2.37 | 0.00 | 5.44 | 3.47 | 0.00 | |

| CCL12 c | 149.46 | 3.70 | 0.00 | 120.42 | 8.28 | 0.00 | |

| CCL20 a | 66.21 | 3.69 | 0.00 | 9.71 | 1.40 | 8.44 | |

| CXCL1 a | 218.46 | 2.71 | 0.00 | 3.42 | 1.21 | 8.44 | |

| CXCL2 a | 9412.93 | 5.23 | 0.00 | 5.63 | 1.22 | 8.44 | |

| CXCL3 a | 75.99 | 2.61 | 0.00 | transcript excluded | |||

| CXCL6 a | 106.35 | 4.74 | 0.00 | 5.24 | 1.17 | 8.44 | |

| CXCL17 b | transcript excluded | 34.53 | 4.15 | 0.00 | |||

| XCL1 a | 0.01 | -4.93 | 0.00 | 2.38 | 0.45 | 15.95 | |

| Cytokines | CSF2 a | 91.78 | 5.87 | 0.00 | 2.20 | 0.57 | 15.95 |

| CSF3 a | 1355.83 | 4.75 | 0.00 | 5.23 | 0.87 | 10.67 | |

| IL-1α a | 2857.26 | 4.63 | 0.00 | 5.46 | 1.60 | 5.52 | |

| IL-1β c | 272.74 | 5.88 | 0.00 | 7.15 | 2.68 | 0.00 | |

| IL-6 a | 522.18 | 4.78 | 0.00 | 4.57 | 1.11 | 8.44 | |

| IL-10 a | 334.63 | 3.67 | 0.00 | 2.83 | 0.48 | 15.95 | |

| IL-24 a | 233.58 | 4.22 | 0.00 | 0.11 | -0.98 | 21.98 | |

| IL-35 / Ebi3 a | 45.77 | 2.46 | 0.00 | 3.15 | 1.10 | 8.44 | |

| Tnf a | 20.44 | 3.20 | 0.00 | 2.42 | 1.13 | 8.44 | |

| Enzymes | Nos2 a | 81737.07 | 11.43 | 0.00 | 13.87 | 1.98 | 5.52 |

| COX-2 / Ptgs2 a | 8.42 | 2.66 | 0.00 | 0.96 | -0.07 | 21.98 | |

| Growth Factors | Artn a | 0.37 | -2.46 | 2.26 | 0.39 | -1.61 | 20.25 |

| Ereg a | 140.20 | 3.15 | 0.00 | 24.38 | 1.91 | 5.52 | |

| Other | PROK2 a | 4443.04 | 7.25 | 0.00 | 8.52 | 1.34 | 8.44 |

3.1.2 Repeated bladder inflammation. A total of 75/92 cytokine transcripts were analysed for magnitude and significance of transcript up-regulation following repeated bladder inflammation. 16 markers (CCL1, CCL3, CCL25, CCL26, CCL28, CXCL3, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-9, IL-13, IL-19, IL-20, IL-27, C5, and IFNγ) were excluded from the repeated inflammation model due to high cycle time (>38 overall mean). One housekeeping gene (18s) was excluded as it was significantly up regulated. FC was therefore calculated normalized to the remaining housekeeping genes (HPRT, ACTB, and GAPDH). Figure 2 shows fold change rank for all cytokines analysed. The top 10 mRNA transcripts up-regulated following repeated bladder inflammation with turpentine are shown in Table 3. Using SAM, we identified 4 mRNAs that were significantly different in turpentine compared to naive (FC >1.5, Δ = 1.61, FDR=0%). Of these, 3 were classified as chemokines (CCL7, CCL12, and CXCL17, and 1 as cytokine (IL-1β), as seen in Table 4.

Figure 2. Ranked mean fold change of inflammatory cytokine mRNA transcripts 24 hours after acute (n=4) and repeated bladder inflammation (n=3), as compared to naive data, showing the increased up-regulation present following acute inflammation as compared with repeated inflammation.

Following significance of microarray analysis, only inflammatory mediators showing up-regulation were significant (q=0%).

3.1.3 Comparison of Inflammatory Mediator Up-regulation Following Acute and Repeated Bladder Inflammation. From a possible list of 92 transcripts, 73 were detected in both models. Table 5 shows the mean rank, standard deviation, and super rank value (SRV) for each transcript examined. Of these IL-1β was significantly up regulated in both (FDR q=0%). Two other chemokines, CCL7 (acute: 272.74 FC; repeated: 7.15 FC), and CCL12 (acute: 17.96 FC; repeated: 7.15 FC), were also significantly up-regulated in both models (FDR q=0%).

Table 5. Super rank values (SRV), consolidating cytokine up-regulation following acute and repeated bladder inflammation with turpentine.

| SRV | Gene | Mean Rank | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nos2 | 3 | 1.41 |

| 2 | CXCL2 | 5 | 0.71 |

| 2 | Prok2 | 5 | 7.07 |

| 4 | IL-1β | 8 | 2.83 |

| 5 | CCL12 | 9.5 | 4.24 |

| 6 | IL-1α | 13.5 | 7.07 |

| 7 | Bdnf | 15 | 8.49 |

| 8 | C3 | 18.5 | 4.95 |

| 9 | IL-35 / Ebi3 | 19 | 4.95 |

| 10 | Ereg | 19.5 | 10.6 |

3.2 Open field behaviour

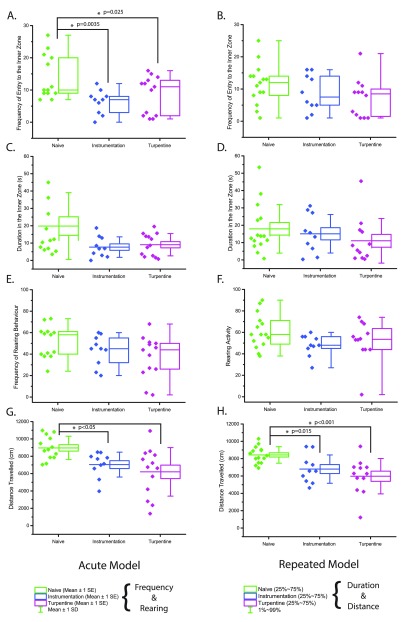

3.2.1 Acute bladder inflammation. Thigmotactic behaviour was observed in animals from both instrumentation and turpentine groups. Animals in both these groups entered the inner zone less frequently compared to naïve (1-way ANOVA, p=0.009). Turpentine animals entered the inner zone 8.6 times (SD 5.84, p=0.025), whereas the instrumentation group averaged 6.3 entries (SD 3.68, p=0.0035), both significant compared to the naïve value of 13.9 entries (SD 6.86) as shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3. Open field behaviour 24hrs after acute ( A, C, E, G; n=9–13) or repeated ( B, D, F, H; 10–16) bladder inflammation.

A/ E - Frequency of entry to the inner zone, B/ F - duration in the inner zone (s), C/ G - rearing frequency, D/ H - total distance travelled (cm).

Duration in the inner zone was not significantly different between groups (Kruskal-Wallis 1-way ANOVA, p=0.192). The median time spent in the inner zone was 11.52s (6.68–29.20), 6.80s (2.88–12.96), and 8.64s (2.56–14.32) for naïve, instrumentation, and turpentine groups respectively ( Figure 3C). Rearing behaviour was not significantly different between groups (1-way ANOVA, p=0.112), with mean rear counts of 51.31 (14.96), 43.20 (14.08), and 37.23 (19.70) for naïve, instrumentation, and turpentine groups respectively ( Figure 3E).

Distance travelled was reduced in both instrumentation (7411.62cm IQR 6584.73–7970.77) and turpentine (6744.29cm IQR 3843.16–8192.87) groups when compared to naïve (Dunn’s post-hoc test p<0.05, 8771.06cm IQR 7860.85–10,188.78; Figure 3G).

3.2.2 Repeated Bladder Inflammation. No significant effect of group was observed on inner zone frequency (p=0.185) or duration (p=0.288), with naïve entering the inner zone an average of 11.5 (6.22) times with a duration of 13.76s (9.6–23.7), instrumentation averaging 8.7 (5.7) entries with a median duration of 14.48s (6.6–27.2), and turpentine entering the inner zone 7.25 (6.0) times, with a median duration of 6.96s (1.76–16.72) ( Figure 3B and D). No difference was seen in rearing activity (p=0.638), with mean rear counts of 56.9 (13.9), 48.6 (7.7), and 52.22 (21.67) for naïve, instrumentation, and turpentine groups respectively ( Figure 3F).

A decrease in distance travelled was seen in both instrumentation (p=0.015, 6797.29cm SD 1637.10) and turpentine (p=0.00026, 5974.04 cm SD 2039.67) groups compared to naïve (8432.59cm SD 953.15; overall 1-way ANOVA p<0.001, Figure 3H).

3.3 c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala in response to open field exposure

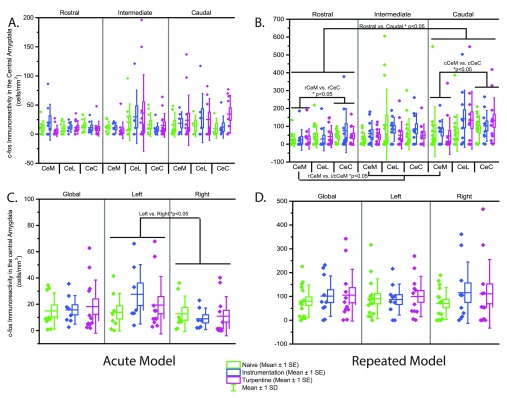

3.3.1 Acute Bladder Inflammation. Higher levels of c-Fos immunoreactivity were seen in the left hemisphere (p=0.0031), localised to the CeM (p=0.032). No other differences in c-Fos immunoreactivity were observed in the central amygdala, and there was no effect of group, as shown in Figure 4, with full c-Fos density data in Table 6.

Figure 4. c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala in response to open field exposure 24hrs after acute ( A, C; n=8–13) or repeated ( D, F; n=7–15) bladder inflammation.

A/ D - Global CeA (central amygdala) c-Fos immunoreactivity, B/ E - right CeA, C/ F - left CeA.

3.3.2 Repeated Bladder Inflammation. The CeC showed higher levels of f-cos immunoreactivity compared to the CeM (p=0.00485).

A rostro-caudal gradient was seen with significantly higher levels of activation observed in the caudal regions (p=0.016). Significant differences were also observed within levels, with the rostral CeL (p=0.013) and caudal CeC (p=0.001) showing higher levels when compared to the CeM. c-Fos immunoreactivity in the CeM exhibited a rostro-caudal gradient, with the rostral region containing fewer positive cells compared to the intermediate (p<0.001) and caudal regions (p=0.002). There was no effect of group on c-Fos immunoreactivity ( Figure 4 and Table 6).

Table 6. c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala in response to open field exposure 24hrs after bladder inflammation.

Data presented as mean (95% confidence interval). Acute: n=8–13; Repeated: n=7–15. Data shown as mean (SD).

| Acute | Repeated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | Mean | SD | (n) | Mean | SD | ||

| Global | Naïve | 9 | 14.90 | 13.68 | 15 | 80.07 | 67.84 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 15.78 | 10.87 | 12 | 109.35 | 106.23 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 17.07 | 19.84 | 10 | 96.32 | 80.11 | |

| CeM | Naïve | 9 | 12.46 | 11.56 | 15 | 38.57 | 40.36 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 16.43 | 15.03 | 11 | 69.85 | 71.48 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 11.94 | 15.28 | 10 | 63.82 | 61.90 | |

| CeL | Naïve | 9 | 18.37 | 17.14 | 15 | 102.51 | 118.49 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 18.77 | 17.53 | 12 | 128.13 | 127.28 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 24.95 | 35.61 | 9 | 106.05 | 105.16 | |

| CeC | Naïve | 9 | 15.39 | 14.41 | 15 | 85.11 | 63.44 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 15.23 | 12.13 | 12 | 125.96 | 146.11 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 14.76 | 15.78 | 10 | 110.56 | 120.35 | |

| Rostral | Naïve | 9 | 13.24 | 10.04 | 15 | 35.68 | 38.87 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 17.71 | 19.50 | 12 | 62.51 | 62.65 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 9.45 | 10.72 | 10 | 55.13 | 74.87 | |

| rCeM | Naïve | 9 | 10.90 | 12.31 | 15 | 21.03 | 36.25 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 20.55 | 30.80 | 12 | 28.87 | 56.66 | |

| Turpentine | 11 | 6.34 | 9.29 | 10 | 24.07 | 58.06 | |

| rCeL | Naïve | 9 | 10.28 | 11.44 | 15 | 43.34 | 64.35 |

| Instrumentation | 7 | 12.30 | 9.29 | 12 | 42.54 | 62.00 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 9.93 | 11.28 | 10 | 28.58 | 65.83 | |

| rCeC | Naïve | 9 | 15.25 | 12.31 | 15 | 36.05 | 36.41 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 9.79 | 11.35 | 12 | 45.95 | 53.22 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 9.28 | 12.69 | 10 | 75.68 | 123.36 | |

| Intermediate | Naïve | 9 | 15.29 | 16.00 | 15 | 76.56 | 102.99 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 13.05 | 11.92 | 12 | 59.38 | 62.55 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 18.86 | 27.82 | 10 | 75.83 | 69.03 | |

| iCeM | Naïve | 9 | 11.97 | 9.85 | 15 | 25.62 | 35.61 |

| Instrumentation | 7 | 11.13 | 9.02 | 12 | 40.17 | 45.61 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 6.68 | 14.15 | 10 | 58.73 | 72.41 | |

| iCeL | Naïve | 9 | 20.63 | 31.44 | 15 | 109.55 | 198.56 |

| Instrumentation | 6 | 29.79 | 45.97 | 12 | 50.20 | 76.14 | |

| Turpentine | 11 | 39.75 | 68.04 | 10 | 82.66 | 66.41 | |

| iCeC | Naïve | 9 | 16.64 | 20.33 | 15 | 56.19 | 87.06 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 9.06 | 10.30 | 12 | 50.95 | 61.50 | |

| Turpentine | 12 | 16.44 | 20.75 | 10 | 85.96 | 87.11 | |

| Caudal | Naïve | 9 | 16.18 | 17.90 | 15 | 107.27 | 136.63 |

| Instrumentation | 8 | 16.56 | 22.56 | 12 | 120.59 | 140.43 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 22.90 | 29.71 | 10 | 114.58 | 102.95 | |

| cCeM | Naïve | 9 | 16.32 | 21.38 | 15 | 69.99 | 139.71 |

| Instrumentation | 6 | 18.82 | 19.43 | 12 | 46.16 | 103.93 | |

| Turpentine | 13 | 23.79 | 43.28 | 10 | 68.25 | 71.35 | |

| cCeL | Naïve | 4 | 14.39 | 18.66 | 15 | 34.54 | 41.57 |

| Instrumentation | 7 | 27.68 | 42.25 | 12 | 189.22 | 283.47 | |

| Turpentine | 9 | 22.45 | 34.54 | 10 | 143.61 | 51.92 | |

| cCeC | Naïve | 4 | 9.90 | 17.47 | 15 | 44.86 | 66.93 |

| Instrumentation | 7 | 12.17 | 19.04 | 12 | 138.74 | 156.49 | |

| Turpentine | 10 | 31.07 | 32.48 | 10 | 136.03 | 81.07 | |

3.4 Correlations

3.4.1 Acute Bladder Inflammation. Overall, there was a positive correlation between rearing activity and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the rostral CeC (Pearson’s ρ=0.44, p=0.01).

Looking at correlations within experimental groups, the naïve group showed the highest levels of correlation, with rearing activity positively correlated with CeC (Overall, right hemisphere, and rostral level; ρ=0.73–80, p<0.05) and CeM (caudal; ρ=0.72, p=0.03). Distance travelled was also positively correlated with caudal c-Fos immunoreactivity in the left central amygdala (ρ=0.8, p=0.02).

In the instrumentation group, there was a positive correlation between duration in the inner zone and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the intermediate CeL (ρ=0.76, p=0.05). No correlations were observed in the turpentine group.

See Table 7 and Table S2 for full details of all correlations.

Table 7. Summary of Pearson co-efficient correlations between behavioural outcomes and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala following both acute and repeated bladder inflammation. Correlations conducted at overall and group level.

Bold* denotes p>0.05. ABBREVIATIONS: N, Naïve; I, Instrumental; T, Turpentine; CeM, medial central amygdala; CeL, lateral central amygdala; CeC, capsular central amygdala.

| Acute | Repeated | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | Frequency | Duration | Rearing | Distance | Frequency | Duration | Rearing | |||||||||||||||||

| Global | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.17 | -0.40 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.51 | -0.07 | 0.01 | -0.30 | -0.58 | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.29 | -0.15 | 0.22 | -0.07 | -0.14 | 0.27 | 0.65 | -0.18 | 0.18 | |

| CeM | 0.20 | 0.09 | -0.10 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.16 | -0.51 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.19 | -0.02 | -0.45 | -0.71* | 0.28 | -0.10 | 0.25 | -0.10 | 0.12 | 0.12 | -0.36 | -0.12 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |

| CeL | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.19 | -0.04 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.20 | -0.32 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.45 | 0.35 | -0.11 | -0.05 | -0.50 | -0.55 | 0.56 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.53 | -0.24 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.21 | -0.22 | 0.01 | |

| CeC | 0.24 | 0.18 | -0.05 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.13 | -0.33 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.56 | -0.09 | 0.22 | -0.11 | -0.52 | 0.40 | -0.29 | 0.23 | 0.17 | -0.34 | 0.12 | -0.27 | -0.52 | 0.13 | 0.73 | -0.44 | 0.29 | |

| Left | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.26 | -0.31 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.52* | 0.22 | -0.02 | -0.08 | -0.51 | -0.53 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.42 | -0.14 | 0.32 | 0.16* | -0.06 | 0.35 | 0.49 | -0.13 | 0.06 | |

| Right | 0.32 | 0.18 | -0.04 | 0.23 | -0.04 | 0.17 | 0.12 | -0.41 | ||||||||||||||||

| -0.07 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.09* | 0.60 | -0.05 | 0.14 | -0.18 | -0.62 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.24 | -0.10 | -0.10 | 0.08 | -0.43* | -0.28 | 0.11 | 0.62 | -0.14 | 0.29 | |

| Rostral | 0.06 | 0.01 | -0.10 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.26 | -0.25 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.41* | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.20 | -0.39 | -0.44 | 0.23 | -0.21 | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.01 | -0.13 | -0.34* | -0.21 | -0.09 | 0.53 | -0.08 | 0.32 | |

| Intermediate | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.16 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.53* | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.10 | -0.15 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.35 | -0.11 | 0.18 | -0.05* | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.66 | -0.18 | 0.14 | |

| Caudal | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.30 | -0.30 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.68* | 0.31 | -0.15 | -0.06 | -0.43 | -0.53 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.39 | -0.16 | 0.35 | 0.08* | -0.15 | 0.33 | 0.60 | -0.10 | 0.08 | |

| N | I | T | N | I | T | N | I | T | N | I | T | N | I | T | N | I | T | N | I | T | N | I | T | |

| Overall | Overall | Overall | Overall | Overall | Overall | Overall | Overall | |||||||||||||||||

3.4.2 Repeated Bladder Inflammation. Overall, there were correlations between frequency, duration, and rearing and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala. Frequency was positively correlated with CeL immunoreactivity in the left hemisphere (ρ=0.35, p=0.03), and CeM immunoreactivity in the right hemisphere (ρ=0.35, p=0.04) and caudal level (ρ=0.39, p=0.02). Duration in the inner zone was positively correlated with rostral CeL (ρ=0.33, p=0.05), caudal CeM (ρ=0.37, p=0.02), and c-Fos immunoreactivity in all intermediate divisions except the right hemisphere (ρ=0.34–0.41, p<0.05). Rearing was negatively correlated with CeM (overall, left, right, and rostral; ρ=-0.43- -0.67, p<0.05), right overall (ρ=-0.41, p=0.05), right CeL (ρ=-0.46, p=0.02), and caudal CeC (ρ=-0.52, p=0.01).

Within the naïve group, there were positive correlations between distance travelled and rostral c-Fos immunoreactivity (overall, left, and CeL; ρ=0.58–0.67, p<0.02). Frequency in the inner zone was positively correlated with caudal (overall, CeM; ρ=0.52–0.61, p<0.05) and rostral CeL c-Fos immunoreactivity (ρ=0.58, p=0.02). Duration in the inner zone was positively correlated with CeC (left, intermediate; ρ=0.59, p=0.02), CeL (left, rostral; 0.53–0.62, p<0.04), caudal CeM (ρ=0.66, p=0.01), left hemisphere (overall, intermediate, caudal; ρ=0.52–0.56, p<0.05), and intermediate (ρ=0.53, p=0.04). No correlations were seen with rearing behaviour.

In the instrumentation group, distance travelled was positively correlated with left CeL (ρ=0.71, p=0.02), and rearing was negatively correlated with left rostral c-Fos immunoreactivity (ρ=-0.93, p=0.02).

In the turpentine group, duration in the inner zone was correlated with intermediate CeM c-Fos immunoreactivity (ρ=0.64, p=0.02). Rearing behaviour was negatively correlated with c-Fos immunoreactivity in the CeM (overall, right, caudal; ρ=-0.71- -0.90, p<0.03), and in the right hemisphere (rostral, CeL; ρ=-0.76- -0.78, p<0.02).

See Table 7 and Table S2 for full details of all correlations.

4. Discussion

Both acute and repeated bladder inflammation up-regulate inflammatory mediator expression, most notably IL-1β, CCL-7, and CCL-12. The fold change was higher in the acute model compared to the repeated, suggestive of a habituation effect when an animal is repeatedly exposed to an inflammatory stimulus. Thigmotactic alterations were observed in both instrumentation and turpentine groups following acute but not repeated bladder inflammation, although reductions in locomotor activity were observed in both models. Investigations into amygdalar c-Fos immunoreactivity following bladder inflammation were inconclusive.

Numerous studies investigating cytokine expression profiles across experimental models of inflammatory pain show results similar to those reported here. IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα are highly expressed in normal bladder tissue ( Pokrywczynska et al., 2013), and have pro-inflammatory actions ( de Oliveira et al., 2011). Additionally, in a study examining cytokine expression following UVB irradiation, five markers also seen in our model of acute bladder inflammation were up-regulated: CCL-4, CCL-7, IL-1β, IL-24, and iNos/Nos2, of which IL-1β and CCL-7 were also seen in our repeated model ( Dawes et al., 2011). In an acute model of pelvic pain (experimental prostatitis) there was increased expression of both CCL7 and CCL12, and seven other chemokines also seen in acute bladder inflammation (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL6, CXCL2, CXCL3, and XCL1), suggesting commonality in inflammatory mediators up-regulated in pelvic inflammatory models ( Quick et al., 2012). Considering the effects of systemic cytokines on behaviour, peripheral IL-1β is associated with decreased activity in the open field, whether administered exogenously ( Campbell et al., 2010; Song et al., 2005), or endogenously up-regulated in response to inflammatory stimuli such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) ( Swiergiel & Dunn, 2007) and intra-plantar carrageenan ( Wen et al., 2014). In a study combining peripheral and systemic effects of cytokines with behaviour and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the amygdala, IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6 reduced activity, with TNFα and IL-1β also associated with increased c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala ( Skelly et al., 2013).

Open field behaviour was reduced in both turpentine and instrumentation groups following acute and repeated bladder inflammation. Distance travelled was decreased in both instrumentation and turpentine groups following acute and repeated bladder inflammation. Exaggerated thigmotactic behaviour (reduced frequency and duration of inner zone visits) was observed only in the acute model, but in both turpentine and instrumentation groups, suggesting catheterisation and instillation of vehicle (olive oil) could be capable of creating an aversive state. Notably, a similar trend was also seen in the repeated, although this did not reach significance due to high levels of variation. Previous studies examining cyclophosphamide (CYP)-induced cystitis revealed mixed effects on behaviour: male mice showed reduced rearing activity but increased time active in the open field four hours after acute injection ( Olivar & Laird, 1999), however a recent study found no difference distance travelled in the open field following CYP treatment in female rats ( Coelho et al., 2014). Other models of visceral inflammation show similarly mixed effects: trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced acute pancreatitis increased immobility in male mice three weeks post-insult ( Cattaruzza et al., 2013), but this effect was not seen in the cerulein-induced model of pancreatitis ( Michalski et al., 2007). Chronic iodoacetamide (IAA)-induced gastritis reduced inner zone activity in female but not male rats ( Luo et al., 2013), whereas acute intra-colonic instillation of mustard oil is reported to either reduce open field locomotor activity ( Maia et al., 2006), or have no effect ( Leite et al., 2012). A similar model of persistent colonic inflammation (deoxycholic acid/DCA) also failed to detect differences in distance travelled in the open field ( Traub et al., 2008). However, intra-plantar CFA has been shown to induce thigmotactic behaviour without reducing distance travelled in the open field, up to 30 days after the original insult, suggesting the effects of acute inflammation can persist ( Parent et al., 2012). Our data supports the idea that inflammation is capable of changing behaviour twenty-four hours after inflammation, but that this effect is not specific to introduction of an irritant into the bladder, and there is an element of habituation, as suggested by the reduced effects observed in the repeated model.

The presence of behavioural alteration in both surgical groups suggests the instillation procedure in itself is enough to alter behaviour. The volume instilled (0.5ml) is within the physiological range, accounting for diurnal variation (Herrera & Meredith, 2010), suggesting the pressure generated would be insufficient to initiate a noxious stretch response. Therefore, olive oil and/or catheterisation are capable of influencing open field behaviour. Anti-nociceptive effects of intra-peritoneal olive oil injection have been shown ( Eidi et al., 2012), and there are numerous studies investigating its purported anti-inflammatory effects in relation to the Mediterranean diet (for review see Lucas et al., 2011), suggesting olive oil may have a protective rather than inflammatory effect. On the other hand, catheterisation is known as a risk factor for cystitis ( Dayts, 2014; Tenke et al., 2014) and pelvic pain ( Nazarko, 2014), suggesting further investigation is required into mechanisms involved in the behavioural alterations we saw in our instrumentation groups.

In the current study, we failed to detect an effect of instrumentation or turpentine on c-Fos immunoreactivity. Increased activity was seen in the lateral (CeL; rostral) and capsular (CeC; caudal) when compared with the medial central amygdala (CeM). The CeL and CeC often considered together as they both receive input from the spinal cord, and brainstem, as well as signals from higher regions such as the cortex, via the thalamus ( Neugebauer et al., 2004). We noted significantly higher levels of activation in the caudal regions of the central amygdala, and although the biological significance of this is not known, it has been previously observed in a model of CYP-induced cystitis ( Bon et al., 1998). No significant effects were seen in the acute model, suggesting the link between open field outcomes and central amygdala activation may be time-dependent, however the lack of robust correlations between behaviour and c-Fos immunoreactivity in this model could also be indicative of reduced involvement of the CeA in the inflammatory-mediated behavioural alterations we observed. Another factor to consider is the higher levels of immunoreactivity seen in the repeated model compared to the acute model. This is observed across all experimental groups, suggesting an environmental effect associated with differences in the housing of the animals.

Other studies involving inflammatory models have shown associated increases in central amygdala activation: c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala was increased 60 minutes after acute intra-peritoneal injection of the gastric hormone CCK (cholecystokinin) ( Rinaman, 2003), and intra-plantar formalin was associated with an increased c-Fos immunoreactivity detectable for up-to 2 ( Rouwette et al., 2011). However, our data is not directly comparable with these studies as the acute timescale considered was considerably shorter than the twenty-four hours we studied. Furthermore, our experiment was designed to investigate whether recent visceral inflammation alters central amygdala activity in response to the open field, as opposed to c-Fos in response to noxious stimuli alone.

A study looking at blood flow and proliferation (cell number and volume) found these measures increased in the central amygdala following spared nerve injury, without a concomitant alteration in elevated plus maze or open field behaviour ( Gonçalves et al., 2008). Nonetheless, thigmotaxis has been observed in association with increased central amygdala activity in peripheral nerve trauma ( Burke et al., 2013), and post-operative incisional models ( Li et al., 2010), emphasising the complexity of central amygdala involvement the generation of thigmotactic behavioural alterations.

We found a significant negative correlations between CeM c-Fos immunoreactivity and rearing behaviour in the repeated turpentine group in particular, suggesting rearing behaviour may be suppressed by CeM activity, although we failed to detect significant alterations in rearing. c-Fos immunoreactivity in the CeM was generally lower than that seen in the CeL/C, as would be expected when considering the CeL and CeC are involved in modulation of incoming noxious signals, whereas the CeM is thought to be more involved in initiation of the behavioural response. Investigations into the direct effect of experimental pain states on amygdala activation have shown up-regulation in the central amygdala, ( Dai et al., 1993; Hayashi et al., 2009; de Lange et al., 2005; Lehner et al., 2006; Rea et al., 2011; Rouwette et al., 2012; Yamashiro et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2010) but none have investigated differences between nuclear subdivisions.

High levels of variability were observed across all data sets, suggesting innate behavioural variation. Numerous studies have shown evidence for a divergent response to stress, and typically note the presence of two behavioural phenotypes – those that have low activity and high neophobia (low activity/high “anxiety”), and those that show higher levels of activity, and low levels of neophobia (high activity/low “anxiety”) ( Koolhaas, 2008; Koolhaas et al., 2010; Mällo et al., 2007; Kabbaj et al., 2000; Landgraf & Wigger, 2002). We noted the presence of distinctive behavioural phenotypes in all groups including naive, characterised by low or high thigmotaxis, and are developing techniques to investigate these differences further – ideally, animals would be behaviourally phenotypes prior to inflammation in order to determine the effects of trait characteristics on state responses. A previous study has shown differential c-Fos expression in animals with differing behavioural phenotypes, namely up-regulation of central c-Fos expression in low activity/high “anxiety” rats ( Salomé et al., 2004). However, although the rats used in our study were the same strain (Wistar, Charles River, UK), those in the Salome study were bred for high and low anxiogenic phenotype in the elevated plus maze (F12), which would likely magnify underlying neurochemical differences present in the original strain. Additionally, the duration of open field exposure was 30 minutes, as compared to the 15 minutes in our study, and it is likely that this would affect the c-Fos activation profile as the animal habituates to its environment.

To fully elucidate the c-Fos response to open field exposure, and determine whether the increase in caudal activation we observed has biological significance, further experiments comparing animals with and without exposure to the open field are required. Investigating cytokine profiles in more individuals would allow further correlation between behavioural outcomes and physiological pathology, and could be particularly instructive in understanding the effect seen in the instrumentation groups. Studies have shown behavioural responses to systemic IL-1β are variable ( Pertsov et al., 2009), and also that acute responses can vary with oestrus cycle in female rats ( Avitsur et al., 1995), suggesting investigations taking this into account may increase the robustness of this study, although a literature survey conducted in 2014 found similar variability between male and female animals ( Prendergast et al., 2014). Furthermore, there are potential refinements that could be applied to this model to facilitate testing behaviour at earlier time points, including reducing the duration of instillation and therefore anaesthesia required by using a more specific and/or potent irritant. Finally, testing of behavioural phenotype prior to treatment allocation would allow more detailed study of whether and how behavioural phenotype modulates responses to visceral inflammation.

In summary, bladder inflammation is associated with a robust up-regulation of peripheral cytokines implicated in pain, inflammation, and behavioural depression, and acutely with increased thigmotaxis, not specific to inflammation. The data on neural correlates are inconclusive, but as increased variation in these outcomes is observed, further studies are required to elucidate mechanisms responsible.

Data availability

Figshare: Cytokine q-RT-PCR, c-Fos immunoreactivity and open field behaviour data in rats following bladder inflammation doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.1394861 ( Morland et al., 2015).

Editorial note

In this article, Morland et al. describe a blind analysis of the open field behaviour of rats under experimental and control conditions, and have included the blinded video data files (see Dataset). Blind analyses can be useful in removing a potential source of bias that could affect the interpretation of results.

We are encouraging interested researchers to conduct new analyses or reanalyses (e.g. replication attempts) on this data. To ensure the integrity of the blinded data, the unblinding lists will only be available upon request from F1000Research ( research@f1000.com). Investigators who wish to publish the results of their analyses in F1000Research will be provided with the unblinding lists shortly after submission of their initial draft manuscript.

Although we hope researchers will perform the analyses before requesting these lists, all requests will be honoured. The corresponding author (AR) is interested to gauge the usage of the unblinding lists and encourages requesters to cc him in when requesting them. For more details about this initiative, please email F1000Research or the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

This work was primarily funded by an MRC CASE award in conjunction with Pfizer to the London Pain Consortium (Wellcome Trust Strategic Award 083259). The manuscript was written under joint-funding from the Europain Collaboration, which has received support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking, under grant agreement AG2013/3347, and NC3Rs (P41508).

v1; ref status: indexed

Supplementary materials

ARRIVE Checklist.

.

Table S1. Cytokine qRT-PCR Array Card Targets.

| Chemokines | Cytokines | Growth

Factors |

Enzymes | Complement

System |

Other | Housekeeping

Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL1 | M- CSF1 | Areg | Alox5 | C3 | Aif1 | 18S |

| CCL2 | GM- CSF2 | Artn | Alox15 | C5 | Edn1 | Actb |

| CCL3 | G- CSF3 | Bdnf | Lta4h | PROK2 | Gapdh | |

| CCL4 | Ifng | Btc | Nos2 | Hprt1 | ||

| CCL5 | IL-1α | Ereg | Ptges | |||

| CCL6 | IL-1β | Fgf7 | Ptgs2 | |||

| CCL7 | IL-2 | Hbegf | ||||

| CCL9 | IL-3 | Kitlg | ||||

| CCL11 | IL-4 | Ngf | ||||

| CCL12 | IL-5 | Nrg1 | ||||

| CCL17 | IL-6 | Nrg1 (exon j) | ||||

| CCL19 | IL-7 | |||||

| CCL20 | IL-9 | |||||

| CCL21b | IL-10 | |||||

| CCL22 | IL-11 | |||||

| CCL24 | IL-12a | |||||

| CCL25 | IL-12b | |||||

| CCL26 | IL-13 | |||||

| CCL27 | IL-14 / Txlna | |||||

| CCL28 | IL-15 | |||||

| CX3CL1 | IL-16 | |||||

| CXCL1 | IL-17 / CTLA-8 | |||||

| CXCL2 | IL-18 | |||||

| CXCL3 | IL-19 | |||||

| CXCL4 / Pf4 | IL-20 | |||||

| CXCL6 | IL-21 | |||||

| CXCL7 / Ppbp | IL-23a | |||||

| CXCL9 | IL-24 | |||||

| CXCL10 | IL-27 | |||||

| CXCL12 | IL-33 | |||||

| CXCL13 | IL-35 / Ebi3 | |||||

| CXCL14 | Lif | |||||

| CXCL16 | Mif | |||||

| CXCL17 | Tnf | |||||

| XCL1 |

Table S2. Full Pearson’s correlations between behavioural outcomes and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the central amygdala.

Bold denotes p<0.05.

| Acute | Repeated | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | Frequency | Duration | Rearing | Distance | Frequency | Duration | Rearing | ||||||||||||||||||

| Global | Overall | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.17 | -0.40 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.51 | -0.07 | 0.01 | -0.30 | -0.58 | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.29 | -0.15 | 0.22 | -0.07 | -0.14 | 0.27 | 0.65 | -0.18 | 0.18 | ||

| CeM | 0.20 | 0.09 | -0.10 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.16 | -0.51 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.19 | -0.02 | -0.45 | -0.71 | 0.28 | -0.10 | 0.25 | -0.10 | 0.12 | 0.12 | -0.36 | -0.12 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.27 | ||

| CeL | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.19 | -0.04 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.20 | -0.32 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.45 | 0.35 | -0.11 | -0.05 | -0.50 | -0.55 | 0.56 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.53 | -0.24 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.21 | -0.22 | 0.01 | ||

| CeC | 0.24 | 0.18 | -0.05 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.13 | -0.33 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.56 | -0.09 | 0.22 | -0.11 | -0.52 | 0.40 | -0.29 | 0.23 | 0.17 | -0.34 | 0.12 | -0.27 | -0.52 | 0.13 | 0.73 | -0.44 | 0.29 | ||

| Left | Overall | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.26 | -0.31 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.52 | 0.22 | -0.02 | -0.08 | -0.51 | -0.53 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.42 | -0.14 | 0.32 | 0.16 | -0.06 | 0.35 | 0.49 | -0.13 | 0.06 | ||

| CeM | 0.11 | 0.01 | -0.16 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.16 | -0.49 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.32 | -0.02 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.32 | 0.26 | -0.20 | -0.18 | -0.64 | 0.28 | -0.05 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | -0.24 | -0.07 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.14 | 0.19 | ||

| CeL | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.29 | -0.07 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.29 | -0.16 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.18 | -0.02 | -0.09 | -0.46 | -0.33 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.55 | -0.13 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.13 | -0.07 | -0.14 | ||

| CeC | 0.13 | 0.02 | -0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.21 | -0.33 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.29 | 0.08 | -0.05 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.59 | 0.06 | -0.12 | 0.09 | 0.25 | -0.63 | 0.12 | -0.21 | 0.23 | -0.07 | -0.31 | 0.17 | -0.26 | -0.43 | 0.22 | 0.48 | -0.42 | 0.26 | ||

| Right | Overall | 0.32 | 0.18 | -0.04 | 0.23 | -0.04 | 0.17 | 0.12 | -0.41 | ||||||||||||||||

| -0.07 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.60 | -0.05 | 0.14 | -0.18 | -0.62 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.24 | -0.10 | -0.10 | 0.08 | -0.43 | -0.28 | 0.11 | 0.62 | -0.14 | 0.29 | ||

| CeM | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.19 | -0.43 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.09 | -0.66 | -0.84 | 0.23 | -0.34 | 0.06 | -0.33 | -0.15 | 0.02 | -0.40 | -0.34 | 0.08 | 0.38 | -0.27 | 0.24 | ||

| CeL | 0.10 | -0.01 | -0.10 | -0.01 | -0.03 | 0.11 | 0.10 | -0.46 | |||||||||||||||||

| -0.08 | 0.22 | -0.21 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.22 | -0.10 | 0.06 | -0.41 | -0.78 | -0.13 | -0.09 | 0.30 | -0.07 | -0.33 | 0.11 | -0.37 | -0.37 | 0.15 | 0.23 | -0.39 | 0.16 | ||

| CeC | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.09 | -0.29 | |||||||||||||||||

| -0.01 | 0.19 | 0.13 | -0.05 | 0.52 | 0.17 | -0.11 | 0.62 | -0.04 | 0.29 | -0.13 | -0.44 | 0.52 | -0.34 | 0.22 | 0.32 | -0.18 | 0.06 | -0.22 | -0.43 | 0.02 | 0.76 | -0.18 | 0.30 | ||

| Rostral | Overall | 0.06 | 0.01 | -0.10 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.26 | -0.25 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.20 | -0.39 | -0.44 | 0.23 | -0.21 | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.01 | -0.13 | -0.34 | -0.21 | -0.09 | 0.53 | -0.08 | 0.32 | ||

| Left | -0.16 | -0.22 | -0.24 | -0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.23 | -0.06 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.58 | -0.09 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.08 | -0.93 | -0.15 | -0.16 | -0.23 | -0.25 | -0.15 | -0.13 | -0.17 | -0.32 | -0.32 | -0.15 | 0.39 | -0.19 | 0.22 | ||

| Right | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.21 | -0.40 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.45 | -0.10 | 0.26 | -0.28 | -0.76 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.48 | -0.09 | -0.34 | 0.22 | -0.05 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.30 | ||

| CeM | 0.00 | -0.06 | -0.09 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.12 | -0.67 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.44 | -0.23 | 0.25 | -0.05 | -0.06 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.26 | -0.34 | -0.78 | -0.90 | 0.23 | -0.02 | -0.21 | -0.28 | 0.28 | -0.12 | -0.18 | 0.01 | -0.01 | 0.12 | 0.26 | -0.16 | ||

| CeL | 0.13 | 0.02 | -0.17 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.26 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.39 | -0.09 | 0.62 | 0.34 | -0.05 | 0.18 | -0.77 | 0.37 | -0.20 | 0.20 | -0.01 | -0.08 | -0.22 | -0.14 | -0.48 | -0.04 | -0.10 | 0.39 | -0.23 | 0.24 | ||

| CeC | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.12 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.49 | -0.18 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.49 | -0.10 | -0.37 | 0.00 | -0.10 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.32 | ||

| Intermediate | Overall | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.16 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.10 | -0.15 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.35 | -0.11 | 0.18 | -0.05 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.66 | -0.18 | 0.14 | ||

| Left | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.04 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.13 | -0.19 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.50 | -0.01 | -0.09 | ||

| Right | 0.19 | 0.10 | -0.03 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.19 | -0.05 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.38 | -0.13 | -0.58 | 0.05 | 0.27 | -0.27 | 0.18 | -0.22 | -0.42 | 0.07 | -0.43 | -0.49 | 0.12 | 0.52 | -0.48 | 0.28 | ||

| CeM | 0.20 | 0.14 | -0.01 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.07 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.64 | -0.28 | -0.58 | 0.50 | 0.09 | -0.45 | 0.04 | -0.26 | -0.18 | -0.02 | -0.39 | -0.57 | -0.01 | 0.62 | -0.16 | 0.36 | ||

| CeL | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.08 | -0.07 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.34 | -0.07 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.12 | 0.15 | -0.19 | -0.06 | -0.19 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.05 | -0.25 | ||

| CeC | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.46 | -0.02 | 0.16 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.26 | -0.02 | 0.22 | -0.01 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.19 | -0.10 | -0.02 | -0.18 | -0.10 | 0.02 | 0.61 | -0.07 | 0.22 | ||

| Caudal | Overall | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.30 | -0.30 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.31 | -0.15 | -0.06 | -0.43 | -0.53 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.39 | -0.16 | 0.35 | 0.08 | -0.15 | 0.33 | 0.60 | -0.10 | 0.08 | ||

| Left | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.23 | -0.32 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.56 | -0.09 | -0.14 | -0.21 | 0.03 | -0.51 | 0.80 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.64 | -0.22 | 0.38 | 0.39 | -0.16 | 0.36 | 0.34 | -0.10 | 0.08 | ||

| Right | 0.08 | -0.08 | -0.19 | -0.09 | -0.10 | 0.00 | -0.03 | -0.37 | |||||||||||||||||

| -0.28 | 0.00 | 0.08 | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.11 | -0.02 | 0.27 | -0.10 | -0.15 | -0.65 | -0.47 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.04 | -0.15 | 0.10 | -0.34 | -0.23 | 0.04 | 0.65 | -0.14 | -0.24 | ||

| CeM | 0.28 | 0.11 | -0.07 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.37 | -0.34 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.31 | -0.03 | 0.22 | 0.61 | -0.02 | 0.23 | 0.66 | 0.09 | -0.04 | -0.01 | -0.27 | -0.88 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.20 | -0.13 | 0.19 | -0.22 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.72 | -0.23 | 0.09 | ||

| CeL | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.06 | -0.03 | -0.09 | -0.02 | -0.06 | -0.34 | |||||||||||||||||

| -0.16 | 0.20 | 0.07 | -0.10 | 0.30 | 0.02 | -0.12 | 0.36 | -0.17 | -0.06 | -0.56 | -0.44 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 0.12 | -0.28 | 0.41 | 0.66 | -0.35 | 0.43 | -0.42 | -0.16 | 0.04 | ||

| CeC | 0.18 | 0.09 | -0.10 | 0.02 | -0.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 | -0.52 | |||||||||||||||||

| -0.16 | 0.05 | 0.07 | -0.25 | 0.13 | 0.43 | -0.11 | 0.21 | 0.22 | -0.40 | -0.33 | -0.59 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.42 | -0.44 | -0.15 | 0.39 | -0.46 | -0.24 | 0.42 | 0.78 | -0.06 | -0.09 | ||

References

- Avitsur R, Donchin O, Barak O, et al. : Behavioral effects of interleukin-1 beta: modulation by gender, estrus cycle, and progesterone. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9(3):234–41. 10.1006/brbi.1995.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Geha PY, Jabakhanji R, et al. : A preliminary fMRI study of analgesic treatment in chronic back pain and knee osteoarthritis. Mol Pain. 2008;4:47. 10.1186/1744-8069-4-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AL: Visualizing circuits and systems using transgenic reporters of neural activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17(5):567–71. 10.1016/j.conb.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar-Fallah A, Alimoradi H, Mehrzadi S, et al. : The neuroprotective effect of tropisetron on vincristine-induced neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology. 2014;41:1–8. 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackbeard J, Wallace VC, O'Dea KP, et al. : The correlation between pain-related behaviour and spinal microgliosis in four distinct models of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(10):1357–67. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon K, Lantéri-Minet M, Michiels JF, et al. : Cyclophosphamide cystitis as a model of visceral pain in rats: a c-fos and Krox-24 study at telencephalic levels, with a note on pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP). Exp Brain Res. 1998;122(2):165–74. 10.1007/s002210050504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NN, Geoghegan E, Kerr DM, et al. : Altered neuropathic pain behaviour in a rat model of depression is associated with changes in inflammatory gene expression in the amygdala. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12(7):705–13. 10.1111/gbb.12080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo M, Dawes JM, Bennett DL: The role of the immune system in the generation of neuropathic pain. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(7):629–42. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70134-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SJ, Meier U, Mardiguian S, et al. : Sickness behaviour is induced by a peripheral CXC-chemokine also expressed in multiple sclerosis and EAE. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(5):738–46. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaruzza F, Johnson C, Leggit A, et al. : Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 mediates chronic pancreatitis pain in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304(11):G1002–12. 10.1152/ajpgi.00005.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheppudira BP, Girard BM, Malley SE, et al. : Involvement of JAK-STAT signaling/function after cyclophosphamide-induced bladder inflammation in female rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297(4):F1038–44. 10.1152/ajprenal.00110.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho A, Oliveira R, Rossetto O, et al. : Intrathecal administration of botulinum toxin type A improves urinary bladder function and reduces pain in rats with cystitis. Eur J Pain. 2014.18(10):1480–9. 10.1002/ejp.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett B: Visceral pain: the importance of pain management services. Br J Pain. 2013;7(1):6–7. 10.1177/2049463713480138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai JL, Zhu YH, Li KY, et al. : Central expression of c-fos protein after peripheral noxious thermal stimulation in awake rats. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1993;14(4):306–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes JM, Calvo M, Perkins JR, et al. : CXCL5 mediates UVB irradiation-induced pain. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(90):90ra60. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayts O: Evidence-based protocol: diagnosis and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection within adult neurocritical care patient population. Nurs Clin North Am. 2014;49(1):29–43. 10.1016/j.cnur.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange RPJ, Geerse GJ, Dahlhaus M, et al. : Altered brain stem responsivity to duodenal pain after a single stressful experience. Neurosci Lett. 2005;381(1–2):144–8. 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira CMB, Sakata RK, Issy AM, et al. : Cytokines and pain. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2011;61(2):255–9 260,–5, 137–42. 10.1016/S0034-7094(11)70029-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidi A, Moghadam-kia S, Moghadam JZ, et al. : Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of olive oil ( Olea europeae L.) in mice. Pharm Biol. 2012;50(3):332–7. 10.3109/13880209.2011.600318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewan EE, Martin TJ: Differential suppression of intracranial self-stimulation, food-maintained operant responding, and open field activity by paw incision and spinal nerve ligation in rats. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(4):854–62. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar-Smith WP, Rice AS: Administration of endocannabinoids prevents a referred hyperalgesia associated with inflammation of the urinary bladder. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(3):507–13. discussion 6A. 10.1097/00000542-200103000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frøkjær JB, Olesen SS, Gram M, et al. : Altered brain microstructure assessed by diffusion tensor imaging in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2011;60(11):1554–62. 10.1136/gut.2010.236620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BM, Cheppudira BP, Malley SE, et al. : Increased expression of interleukin-6 family members and receptors in urinary bladder with cyclophosphamide-induced bladder inflammation in female rats. Front Neurosci. 2011;5:20. 10.3389/fnins.2011.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves L, Silva R, Pinto-Ribeiro F, et al. : Neuropathic pain is associated with depressive behaviour and induces neuroplasticity in the amygdala of the rat. Exp Neurol. 2008;213(1):48–56. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grégoire S, Michaud V, Chapuy E, et al. : Study of emotional and cognitive impairments in mononeuropathic rats: Effect of duloxetine and gabapentin. Pain. 2012;153(8):1657–63. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RE, Zubieta JK, Scott DJ, et al. : Traditional Chinese acupuncture and placebo (sham) acupuncture are differentiated by their effects on mu-opioid receptors (MORs). NeuroImage. 2009;47(3):1077–85. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Kondo T, Ishimatsu M, et al. : Expression of the TRPM8-immunoreactivity in dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating the rat urinary bladder. Neurosci Res. 2009;65(3):245–51. 10.1016/j.neures.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Calvo M, Karu K, et al. : A clinically relevant rodent model of the HIV antiretroviral drug stavudine induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2013;154(4):560–75. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel M, Lu P, Cummons TA, et al. : The persistence of a long-term negative affective state following the induction of either acute or chronic pain. Pain. 2008;140(3):436–45. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar SI, Hasnie FS, Sellaturay S, et al. : The anti-hyperalgesic actions of the cannabinoid anandamide and the putative CB2 receptor agonist palmitoylethanolamide in visceral and somatic inflammatory pain. Pain. 1998;76(1–2):189–99. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar SI, Scott HC, Rice ASC: Inflammation of the rat urinary bladder is associated with a referred thermal hyperalgesia which is nerve growth factor dependent. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(3):442–8. 10.1093/bja/83.3.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R, Andersson KE, Persson K: Nerve-mediated bladder contraction is impaired by cytokines: involvement of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;476(3):221–227. 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)02178-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbaj M, Devine DP, Savage VR, et al. : Neurobiological Correlates of Individual Differences in Novelty-Seeking Behavior in the Rat: Differential Expression of Stress-Related Molecules. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6983–6988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, et al. : Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(6):e1000412. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontinen VK, Kauppila T, Paananen S, et al. : Behavioural measures of depression and anxiety in rats with spinal nerve ligation-induced neuropathy. Pain. 1999;80(1–2):341–6. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00230-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas JM: Coping style and immunity in animals: making sense of individual variation. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(5):662–7. 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Coppens CM, et al. : Neuroendocrinology of coping styles: towards understanding the biology of individual variation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31(3):307–21. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf R, Wigger A: High vs Low Anxiety-Related Behavior Rats: An Animal Model of Extremes in Trait Anxiety. Behav Genet. 2002;32(5):301–314. 10.1023/A:1020258104318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner M, Taracha E, Skórzewska A, et al. : Behavioral, immunocytochemical and biochemical studies in rats differing in their sensitivity to pain. Behav Brain Res. 2006;171(2):189–98. 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite Gde O, Fernandes CN, de Menezes IR, et al. : Attenuation of visceral nociception by α-bisabolol in mice: investigation of mechanisms. Org Med Chem Lett. 2012;2(1):18. 10.1186/2191-2858-2-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CQ, Zhang JW, Dai RP, et al. : Surgical Incision Induces Anxiety-Like Behavior and Amygdala Sensitization: Effects of Morphine and Gabapentin. Pain Res Treat. 2010;2010:1–10. 10.1155/2010/705874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Shkedy Z, Burzykowski T, et al. : An investigation on performance of Significance Analysis of Microarray (SAM) for the comparisons of several treatments with one control in the presence of small-variance genes. Biom J. 2008;50(5):801–23. 10.1002/bimj.200710467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas L, Russell A, Keast R: Molecular mechanisms of inflammation. Anti-inflammatory benefits of virgin olive oil and the phenolic compound oleocanthal. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(8):754–68. 10.2174/138161211795428911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Wang T, Liang S, et al. : Experimental gastritis leads to anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in female but not male rats. Behav Brain Funct. 2013;9:46. 10.1186/1744-9081-9-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, Fisher M, O'Collins V, et al. : Reprint: Good laboratory practice: preventing introduction of bias at the bench. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(2):221–3. 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia JL, Lima-Júnior RC, David JP, et al. : Oleanolic Acid, a pentacyclic triterpene attenuates the mustard oil-induced colonic nociception in mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29(1):82–5. 10.1248/bpb.29.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]