ABSTRACT

Background:

Ventilatory strategy and specifically positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) can modulate the inflammatory response and pulmonary-to-systemic translocation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Both inflammation and ventilatory pattern may modify brain activation, possibly worsening the patient's outcome and resulting in cognitive sequelae.

Methods:

We prospectively studied Sprague–Dawley rats randomly assigned to undergo 3 h mechanical ventilation with 7 mL/kg tidal ventilation and either 2 cmH2O or 7 cmH2O PEEP after intratracheal instillation of LPS or saline. Healthy nonventilated rats served as baseline. We analyzed lung mechanics, gas exchange, lung and plasma cytokine levels, lung apoptotic cells, and lung neutrophil infiltration. To evaluate brain neuronal activation, we counted c-Fos immunopositive cells in the retrosplenial cortex (RS), thalamus, supraoptic nucleus (SON), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and central amygdala (CeA).

Results:

LPS increased lung neutrophilic infiltration, lung and systemic MCP-1 levels, and neuronal activation in the CeA and NTS. LPS-instilled rats receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP had less lung and systemic inflammation and more c-Fos-immunopositive cells in the RS, SON, and thalamus than those receiving 2 cmH2O PEEP. Applying 7 cmH2O PEEP increased neuronal activation in the CeA and NTS in saline-instilled rats, but not in LPS-instilled rats.

Conclusions:

Moderate PEEP prevented lung and systemic inflammation secondary to intratracheal LPS instillation. PEEP also modified the neuronal activation pattern in the RS, SON, and thalamus. The relevance of these differential brain c-Fos expression patterns in neurocognitive outcomes should be explored.

Keywords: Experimental, inflammation, mechanical ventilation, neuronal activation, PEEP

Abbreviations: ALI, Acute lung injury, ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, BAS, Basal, CeA, Central amygdala, IL, Interleukin, LPS, lipopolysaccharide, MAP, Mean arterial pressure, MCP, Monocyte chemoattractant protein, MV, Mechanical ventilation, NTS, Nucleus tractus solitarius, PEEP, Positive end-expiratory pressure, PVN, Paraventricular nucleus, RS, Retrosplenial cortex, SEM, Standard error of the mean, SON, Supraoptic nucleus, TNF, Tumor necrosis factor, VILI, Ventilator-induced lung injury, VT, Tidal volume

INTRODUCTION

Endotracheal intubation increases the risk of bacterial colonization of the lower respiratory tract, and may eventually lead to pneumonia or pneumonitis (1). This event is clinically relevant in critically ill patients attended in intensive care units (ICU) and can trigger acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (2, 3). Mechanical ventilation (MV) also increases the risk of infection and can contribute to the dissemination of bacteria or bacterial products (3–6). The translocation of inflammatory mediators could compromise the functionality of different organs and systems, including the brain, and may be involved in ICU-acquired delirium or post-ICU cognitive decline. The recent literature reflects growing interest in lung–brain crosstalk (7, 8), and its possible role in the development and prevention of cognitive impairment (9, 10) in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients.

A protective ventilatory strategy with low tidal volume (Vt) prevents ALI and inflammatory decompartmentalization after intratracheal instillation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in rabbits (11). Conversely, adverse ventilatory strategies cause pulmonary-to-systemic translocation of LPS or bacteria, thereby promoting the dissemination of inflammation (12, 13). Whitehead et al. (4) explored the effect of MV on cytokine response to intratracheal LPS or saline using different ventilatory patterns in an ex vivo rat model. They found TNFα levels in bronchoalveolar lavage in lungs from animals instilled with saline undergoing MV were lower with low Vt; however, this protective effect of low Vt was dampened in animals instilled with LPS. Likewise, optimizing positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) could help prevent ALI and inflammation (14, 15) and neurological alterations.

The central nervous system (CNS) receives both humoral and sensory inputs, which are regulated through the central autonomic network, and the brain's neuroimmune system helps maintain body homeostasis. In a mouse model of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI), MV triggered apoptosis in hippocampal neurons via vagal and dopaminergic pathways (16). However, how protective MV can affect brain homeostasis remains unresolved (7). In a previous study using a rodent model of VILI, we found that different levels of Vt resulted in early differential neuronal activation, as reflected in increased expression of c-Fos protein (8). The brain can probably sense differential inputs from pulmonary stretch receptors that change with Vt and PEEP level (17).

The optimal PEEP level is a matter of debate, and its contribution in modulating lung–brain crosstalk is unknown. We hypothesize that optimizing PEEP level immediately after tracheal instillation could be crucial to prevent local and systemic inflammation secondary to LPS and MV. Moreover, we postulate that PEEP might also modify the pattern of neuronal activation in the brain and changes in activation patterns could help elucidate which areas of the brain participate in this modulatory response.

In this study, to ascertain the best level of PEEP to prevent local inflammation and systemic dissemination and to explore the influence of PEEP level on neuronal activation, we investigated the effects of two PEEP levels on local, systemic, and brain responses immediately after intratracheal instillation of LPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation and measurements

In accordance with the European Commission Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experimentation, the university's animal ethics committee approved the study. We studied 38 adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (mean weight, 348 ± 32 g) housed in standard conditions with a 12-h light–dark cycle and food and water ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized with 75 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mL/kg xylazine intraperitoneally, placed supine, and tracheotomized. An endotracheal tube (2 mm inner diameter) was inserted and tightly tied to avoid air leaks, and the rats were ventilated using a Servo-300 ventilator (Maquet; Solna, Sweden) while paralyzed with repeated doses of succinylcholine chloride. Anesthesia and muscle relaxation were administered every 45 min. Airway pressure was monitored via a side port in the tracheal tube using a pressure transducer (Valydine MP45, Valydine Engineering, Northridge, CA). The left carotid artery was cannulated and connected to a pressure transducer (Transpac Monitoring Kit, Abbot, Sligo, Ireland) to monitor mean arterial pressure (MAP). The right jugular vein was cannulated for fluid infusion (10 mL/kg/h). Blood and airway pressures were routed to an amplifier (Presograph, Gould Godart, The Netherlands), converted to digital (Urelab, Barcelona, Spain), and recorded in a personal computer (Anadat-Labdat Software, RTH InfoDat, Montreal, Canada).

Rats were randomly assigned to one of five experimental groups: basal group, in which animals were immediately exsanguinated after anesthesia and no LPS or MV was not administered (n = 6); low-PEEP-saline group (SAL-2), in which animals were ventilated with 2 cmH2O PEEP after saline instillation (n = 8); low-PEEP-LPS group (LPS-2), in which animals were ventilated with 2 cmH2O PEEP after LPS instillation (n = 8); moderate-PEEP-saline group (SAL-7), in which animals were ventilated with 7 cmH2O PEEP after saline instillation (n = 8); and moderate-PEEP-LPS group (LPS-7), in which animals were ventilated with 7 cmH2O PEEP after LPS instillation (n = 8). During preparation, all rats were ventilated with 7 mL/kg Vt and 2 cmH2O PEEP, at 46 breaths/min, FiO2 = 0.4, and 1:2 inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio. Immediately after a 15-min stabilization period, 200 μg/kg LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5 serotype (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) diluted in a total volume of 200 μL of sterile saline was intratracheally instilled; animals were rotated in both lateral decubitus positions to facilitate homogeneous distribution. MV with Vt 7 mL/kg was maintained for 3 h, and at the end of this period arterial blood gases and respiratory system mechanics (inspiratory and expiratory pause) were recorded. MAP was continuously monitored.

At the end of the 3-h MV period, rats were euthanized by exsanguination. For protein determinations, 7 mL of blood from each animal was centrifuged and plasma was stored at −80° C. Lungs and brains were removed and frozen for tissue analyses. The left lung was fixed for histological analysis.

Histological analysis

Left lungs were fixed by instillation of 4% buffered formaldehyde at a pressure of 5 cmH2O and then immersed in the same fixative. Lungs were embedded in paraffin and sliced at 5 μm for histopathology and for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay. After hematoxylin-eosin staining, two investigators (MEQ, JLA), blinded to experimental groups, assessed alveolar neutrophil infiltration by counting the neutrophils in 50 random fields per animal at a magnification of ×400 using ImageJ v1.36 (Wayne Rasband, NIH, USA) (18).

TUNEL assays in lung tissue

The TUNEL assay was performed using the In situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche Applied Science, Barcelona, Spain), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, deparaffinized sections were permeabilized, rehydrated, and digested with proteinase K (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Barcelona) at 37°C for 30 min and then washed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 15 min. Then, sections were incubated with TUNEL reaction mixture, containing TdT and fluorescein-dUTP, at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. Slides were washed in PBS, mounted with Fluoromount Aqueous Mounting Medium (Sigma-Aldrich), and viewed with a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using an excitation wavelength of 450–500 nm. To identify and count TUNEL-positive cells, 10 to 15 lung fields were captured and examined with a magnifying power of ×100 (ImageJ 1.40 g, Wayne Rasband).

Plasma and lung protein immunoassays

We measured interleukin (IL) IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-10; tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α; and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 levels in plasma and lung tissue homogenates with a rat multiplex immunoassay kit (RCYTO-80K MILLIPLEX MAP Rat Cytokine/Chemokine Panel, Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) using high-throughput multiplex Luminex technology (Luminex 200 System, Luminex, Austin, TX). Analyses of all samples, standards, and controls were run in duplicate.

Brain immunohistochemistry

To investigate the functional location of neural activity induced by PEEP, we examined brain c-Fos expression. C-Fos Protein is the product of the immediate early gene c-fos, and it has been widely used as a marker of neuronal activity. Its basal expression is low but increases quickly induced by a variety of stimuli. At the end of the experiments, rats’ brains were removed and immediately frozen and stored at −80°C. Later, the brains were cut into 20-μm coronal sections (Cryostat CM1900, Leica Microsystems, Barcelona, Spain) and stored at −80°C. Some sections were stained with cresyl violet to identify the regions of interest, and additional sections were processed for immunohistochemistry to assess c-Fos expression in different areas (8): the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), supraoptic nucleus (SON), central amygdala (CeA), retrosplenial cortex (RS), and thalamus. After immunostaining, activated areas were identified by light microscopy (DM250, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with the aid of a stereotaxic atlas. Brain sections were digitized; the c-Fos-positive cells were evaluated according to the staining intensity of cells, and then semiquantified using Image J software (ImageJ 1.40 g, Wayne Rasband) (8). An optimal threshold was set for all sections to minimize any background signal.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 21; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) under the supervision of an expert statistician. Results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All data were tested for homogeneity of variance (Levene's test). Statistical analysis was performed with one-way analysis of variance (17) followed by post-hoc Dunnett t-test for comparisons between MV groups and the basal group (nonventilated animals). Differences between the two levels of PEEP were assessed by Student t tests separately for each saline or LPS instillation groups. MAP was compared by one-way ANOVA for repeated measures. Level of significance was set at P < 0.05 and P < 0.1 was considered to be a trend, because approaching, although not reaching, the significant level.

RESULTS

Physiological parameters

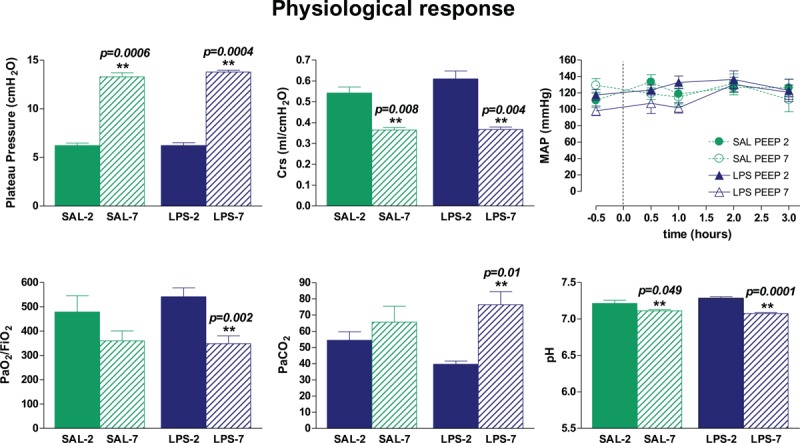

MAP was similar in all groups. In animals ventilated with 7 cmH2O PEEP (PEEP-7), respiratory system compliance decreased (Fig. 1) (P = 0.008 in SAL; P = 0.0042 in LPS). Animals ventilated with PEEP-7 had lower pH (P = 0.049 in SAL; P = 0.0001 in LPS) and higher PaCO2 (P = 0.01 in LPS) than those ventilated with 2 cmH2O PEEP (PEEP-2), and LPS-instilled animals receiving PEEP-7 had lower PaO2/FiO2 than LPS-instilled animals receiving PEEP-2 (P = 0.002).

Fig. 1.

Course of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and respiratory characteristics after mechanical ventilation.

MAP was similar in all experimental groups. Plateau pressure after 3 h of mechanical ventilation was higher in animals receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP (PEEP-7). Respiratory system compliance (Crs), pH, and PaO2/FiO2 were lower and PaCO2 was higher in PEEP-7 than in those receiving 2 cmH2O PEEP (PEEP-2). Bars represent means ± SEM. ∗∗P < 0.05 PEEP-7 vs. PEEP-2.

Inflammatory response

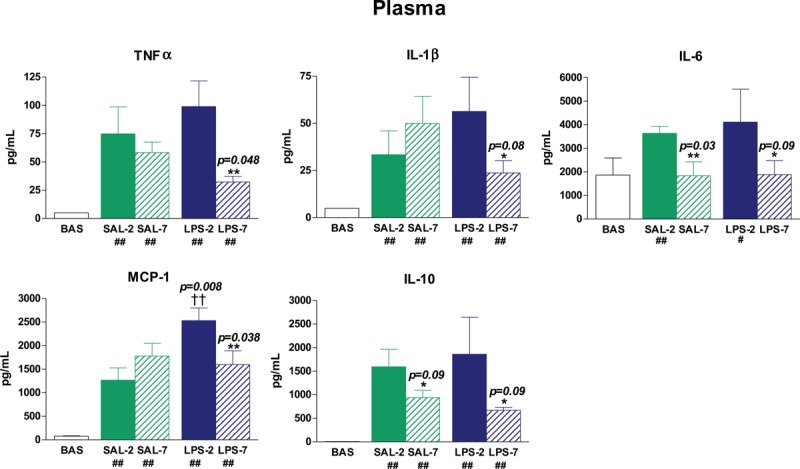

In basal rats, TNFα, IL-1β, MCP-1, and IL-10 plasma levels were low. By contrast, all rats undergoing tracheal instillation and MV presented a global inflammatory response. Moreover, the administration of LPS increased MCP-1 levels in plasma (P = 0.008 in PEEP-2). In LPS-instilled animals, TNFα (P = 0.048), IL-1β (P = 0.08), IL-6 (P = 0.09), MCP-1 (P = 0.038), and IL-10 (P = 0.09) levels were higher in PEEP-2 than in PEEP-7 (Fig. 2). In saline-instilled animals, IL-6 (P = 0.03) and IL-10 (P = 0.09) plasma levels were higher in PEEP-2 than in PEEP-7.

Fig. 2.

Plasma levels of cytokines.

After 3 h of mechanical ventilation, plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines were higher than in basal (BAS) nonventilated animals (# P < 0.1 and ## P < 0.05 compared with BAS). LPS-instilled rats had higher MCP-1 levels than saline-instilled rats (†† P < 0.05). LPS-instilled rats receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP (LPS-7) presented lower levels of inflammatory mediators than those receiving 2 cmH2O PEEP (LPS-2). The application of 7 cmH2O PEEP (PEEP-7) reduced IL-10 levels in both saline-instilled and LPS-instilled animals. The application of PEEP-7 also reduced IL-6 levels in saline-instilled rats. Bars represent means ± SEM. ∗ P < 0.1 and ∗∗ P < 0.05 comparing PEEP-7 vs. 2 cmH2O PEEP.

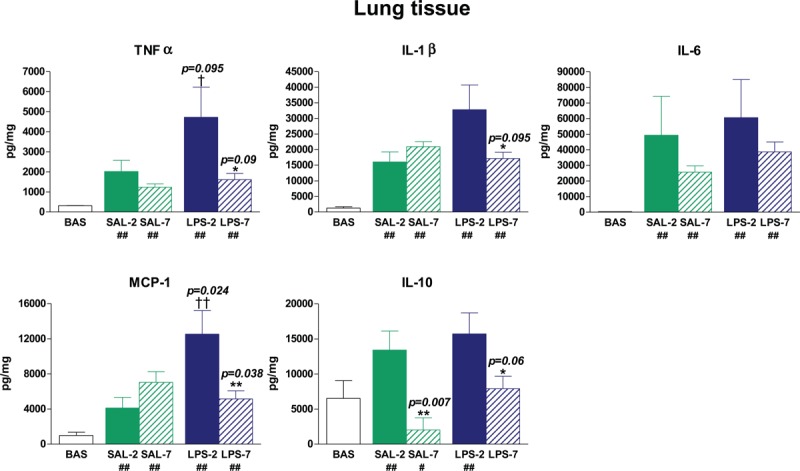

Similar effects were observed in lung tissue homogenates (Fig. 3). TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1 levels were low in lung tissue homogenates of basal rats. Intratracheal instillation of LPS increased MCP-1 (P = 0.024) and TNFα (P = 0.095) levels in lungs. In LPS-instilled animals, PEEP-7 reduced TNFα (P = 0.09), IL-1β (P = 0.095), MCP-1 (P = 0.038), and IL-10 (P = 0.06) levels. In saline-instilled animals, PEEP-7 reduced IL-10 (P = 0.007).

Fig. 3.

Lung levels of cytokines.

After 3 h of mechanical ventilation, lung levels of cytokines were higher than in basal (BAS) non-ventilated animals (# P < 0.1 and ## P < 0.05 compared with BAS). LPS-instilled rats had higher MCP-1 and TNFα levels than saline-instilled rats († P < 0.1 and †† P < 0.05). LPS-instilled rats receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP (LPS-7) presented lower levels of TNFα, IL-1β, MCP-1, and IL-10 than those receiving 2 cmH2O PEEP (LPS-2). The application of 7 cmH2O PEEP reduced IL-10 levels in both saline-instilled and LPS-instilled animals. Bars represent means ± SEM. ∗ P < 0.1 and ∗∗ P < 0.05 comparing 7 cmH2O PEEP vs. 2 cmH2O PEEP.

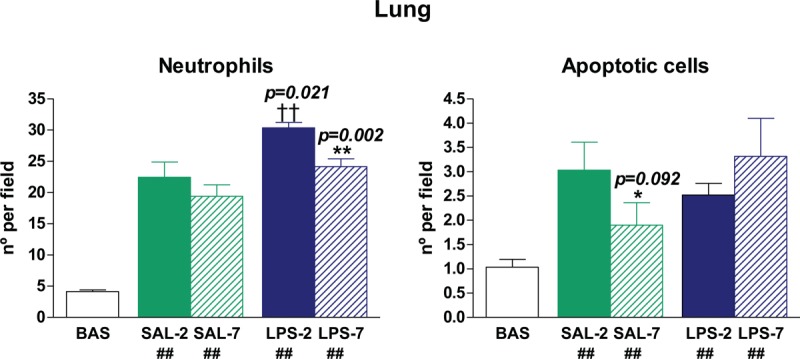

Lung neutrophil infiltration and apoptosis

Low levels of neutrophils and apoptotic cells were found in the lungs of basal animals. Neutrophil infiltration was higher in LPS-instilled than in saline-instilled animals (P = 0.021) (Fig. 4), but PEEP-7 significantly reduced the number of infiltrated neutrophils in the lung (P = 0.002). All instilled-MV rats had TUNEL-positive cells in lung sections. In LPS-instilled rats, there were no differences between the two levels of PEEP; by contrast, in saline-instilled rats, there were fewer TUNEL-positive cells in PEEP-7 than in PEEP-2 (P = 0.092) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Neutrophilic infiltration and apoptotic cell counts in lung.

Mechanical ventilation promotes lung neutrophilic infiltration and apoptosis (## P < 0.05 compared with BAS group). LPS-instilled rats had higher lung neutrophil infiltration than saline-instilled rats (†† P < 0.05), but there were no differences in apoptosis rates. LPS-instilled rats receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP presented lower levels of neutrophils than those receiving cmH2O PEEP. Bars represent means ± SEM. ∗ P < 0.1 and ∗∗ P < 0.05 comparing 7 cmH2O PEEP vs. 2 cmH2O PEEP.

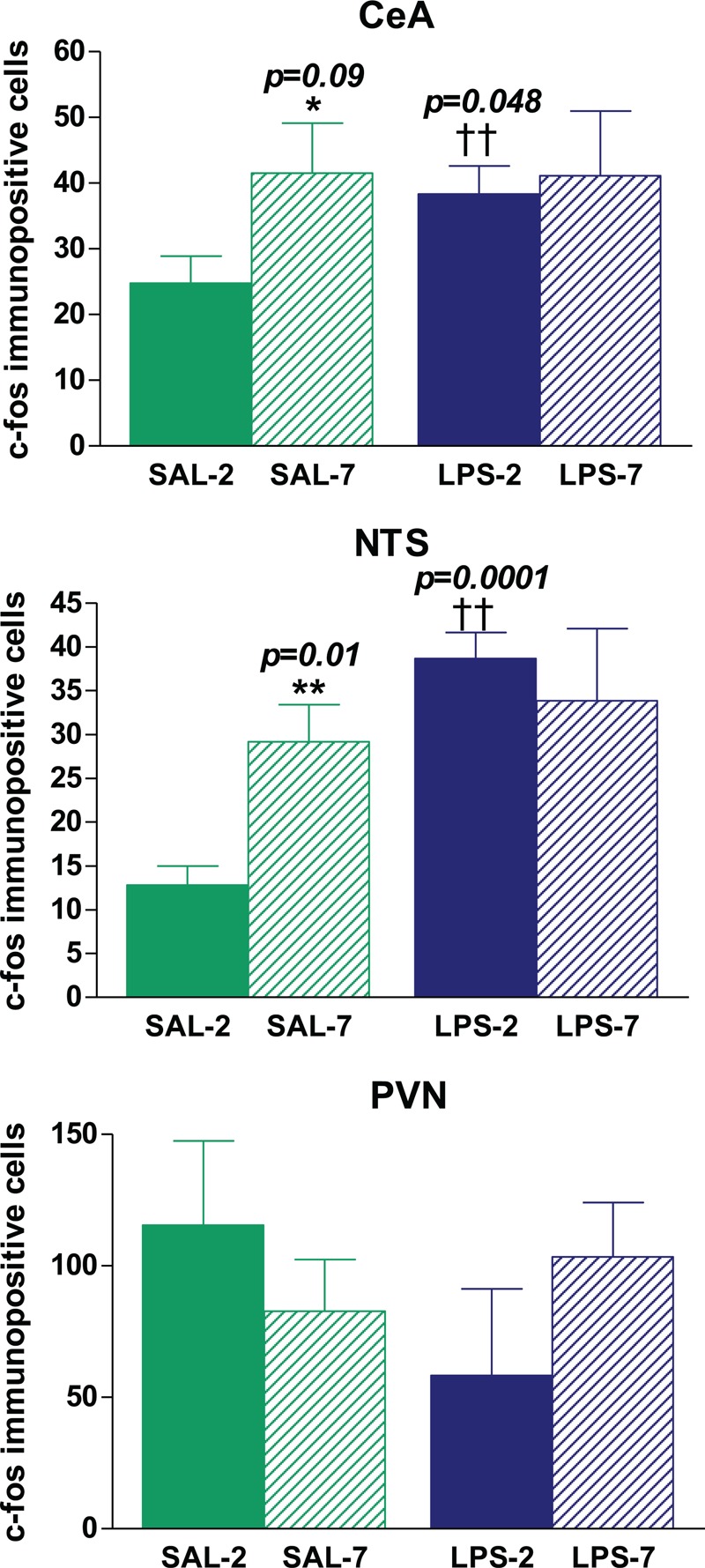

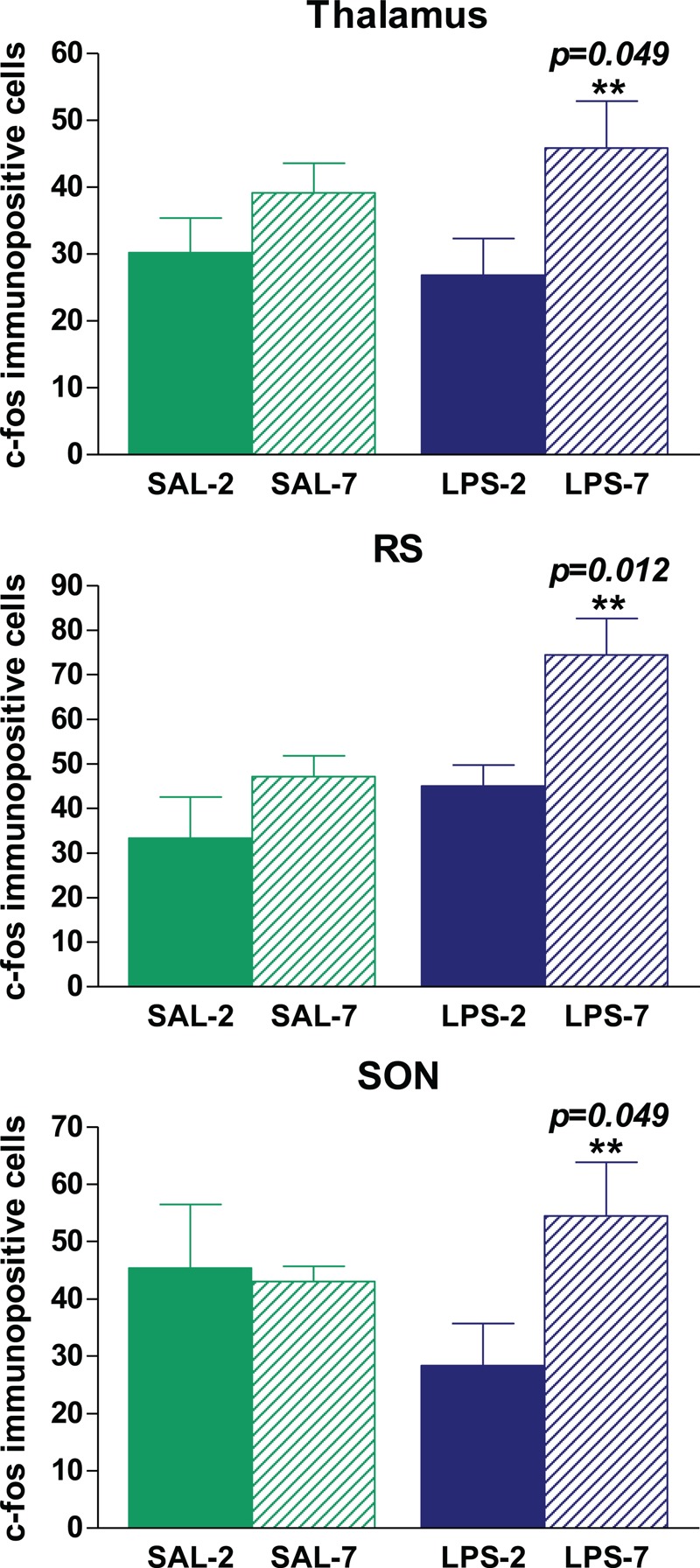

c-Fos immunopositive brain areas

We found no c-Fos-immunopositive cells in brains from healthy, nonventilated animals (see Figures, Supplemental Digital Content 1). By contrast, all rats that underwent instillation and MV presented c-Fos immunoreactivity in all areas studied (Figs. 5 and 6 and Figures, Supplemental Digital Content 1). Neuronal activation was higher in LPS-instilled rats than in saline-instilled rats in CeA (P = 0.048) and NTS (P = 0.0001). PEEP level had no effect on neuronal activation in these areas in LPS-instilled rats. In saline-instilled rats, however, neuronal activation in the CeA (P = 0.09) and NTS (P = 0.01) was higher in animals receiving PEEP-7 than in those receiving PEEP-2. In the PVN, no differences in neuronal activation were found between groups. LPS-7 rats had more c-Fos-immunopositive cells than LPS-2 rats in the RS (P = 0.012), SON (P = 0.049), and thalamus (P = 0.049), but there were no differences between SAL-7 and SAL-2 rats (Figs. 5 and 6). No differences between brain hemispheres were found. Supplemental Digital Content 1, contains representative images of c-Fos-immunopositive cells in the different areas of the brain explored.

Fig. 5.

Quantification of c-Fos immunopositive cells per field in different areas of the brain.

No immunopositive cells were found in nonventilated rats. LPS-instilled rats had more immunopositive cells in the CeA and NTS than saline-instilled rats (†† P < 0.05). Saline-instilled rats receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP had more immunopositive cells in the CeA and NTS than saline-instilled rats receiving 2 cmH2O PEEP(∗ P < 0.1 and ∗∗ P < 0.05). No differences between groups were found in the PVN. Bars represent means ± SEM.

Fig. 6.

Quantification of c-Fos-immunopositive cells per field in different areas of the brain.

No immunopositive cells were found in nonventilated BAS rats. The administration of LPS did not modify the number of immunopositive cells in the thalamus, RS, or SON. LPS-instilled rats receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP had more immunopositive cells in the thalamus, RS, and SON than those receiving 2 cmH2O PEEP (∗∗ P < 0.05). Bars represent means ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of our study is that applying moderate PEEP immediately after intratracheal LPS instillation prevented lung inflammation and the dissemination of inflammatory mediators. Our results also demonstrate that the pattern of neuronal activation that can be modified by intratraqueal instillation of LPS might also be modulated by PEEP.

Intratracheal LPS instillation has been widely used to mimic contamination of the endotracheal tube and upper airways and the inflammatory response secondary to local infection in animal models of ALI/ARDS (19). In the present study, intratracheal LPS instillation contributed to local inflammation and neutrophil recruitment in the lungs of animals undergoing MV with low PEEP.

Regarding the use of higher levels of PEEP to protect from the adverse effects of LPS instillation, a recent experimental study demonstrated that higher PEEP decreased ventilation heterogeneities in the first 2 h following bronchoaspiration (20). In the present study, we found PEEP-7 was beneficial in preventing the inflammatory response secondary to LPS administration, despite a certain degree of lung overdistension in these rats. PEEP-7 decreased static lung compliance, probably by increasing alveolar dead space (21, 22). PEEP-7 may have expanded aerated airspaces, inducing overinflation, probably because of the low potential of recruitment in these lungs. The height of the rat thorax is around 2 cm (compared with 8 cm in humans), so PEEP-7 level would correspond to 26–28 cmH2O in humans, which is excessive (23). This could favor ventilation/perfusion mismatch and might contribute to the hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis observed in both saline- and LPS-instilled rats receiving PEEP-7. PEEP decreased both the local inflammatory and systemic inflammatory responses to LPS; we hypothesize that this trend to decrease resulted from PEEP's effect of reducing strain and shear stresses during the repeated opening and closing of lung units (15, 24). Several authors have also reported that pulmonary cells respond differently to different insults (25). Hypercapnic acidosis modulates inflammation in VILI (26) but not in lung injury caused by bacterial pneumonia (27). In view of our results, we cannot rule out a protective contribution from hypercapnic acidosis in our model. We postulate that in the rats receiving LPS instillation and MV PEEP-7 prevented both local and systemic inflammatory responses induced by LPS, even when these PEEP levels promoted overdistension.

Intratracheal LPS also induced a CNS response evidenced by c-Fos immunoreactivity in the CeA and NTS, corroborating organ cross-talk in the proinflammatory response. The CeA is involved in processing autonomic information and receives sensory inputs and inputs from the NTS, which is itself a primary detector of cytokines (28). Vagal afferent neurons can be activated by peripheral LPS, so vagal innervation could explain how intratracheal LPS could cause neuronal activation before a systemic response develops (29). In fact, in a recent study we showed that after stimulation with LPS, pulmonary epithelial cells release different mediators that significantly affect brain cells in culture (30).

Furthermore, the results of the present study corroborate our previous finding that MV in itself promotes c-Fos immunoreactivity in several areas of the brain (8). Beyond this finding, our results show that PEEP can contribute to the differential regional regulation of neuronal activity that accompanies the pulmonary and systemic inflammatory cascades. Although PEEP may affect the cerebral circulation by hemodynamic (31) and CO2-mediated mechanisms (21), in our study, similar levels of hypercapnia in PEEP-7 animals resulted in different activation patterns in the brain depending on whether they received LPS or saline. Even in the absence of LPS instillation, PEEP-7 resulted in increased neuronal activation in the NTS and CeA. We also observed neuronal activation in PVN and CeA independent of inflammatory mediators in the LPS-7 group. PEEP-7 immediately after tracheal LPS instillation prevents the proinflammatory cascade. We speculate that PEEP results in neuronal activation before a systemic response is manifest, and this neuronal activation is achieved through neural pathways. The NTS controls the response to baroreflex stimuli (29), so information about lung stretching could reach the NTS in the brain stem via the vagus nerve (32).

The vagal pathway plays a crucial role in lung–brain communication by activating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex, which attenuates VILI (16, 32). The sensory nerves respond to mechanical forces and to tissue damage by inhibiting the local activation of macrophages, enabling targeted control of the damage focused only on maintaining local tissue integrity without compromising the global immune response.

Various studies indicate that brain regions (hippocampal nuclei, SON, and PVN) respond to acute stress by increasing immunoreactivity to c-Fos (33, 34). In the present study, RS, SON, and thalamus immunoreactivity to c-Fos was clearly higher in LPS-instilled rats receiving PEEP-7 than in LPS-instilled rats receiving PEEP-2 or in saline-instilled rats receiving either PEEP level. Thus, it seems that moderate PEEP could contribute to modulating not only the inflammatory response but also neuronal activation in these discrete areas. Interestingly, in our previous study (8), we also observed increased immunoreactivity to c-Fos in the RS and thalamus in rats receiving high Vt without PEEP and in spontaneously breathing rats. Our present data cannot determine whether neuronal activation in RS, SON, and thalamus is definitely linked with the modulation of inflammation observed in LPS-7 animals, and future studies should clarify this point.

Limitations of the study

Caution is warranted in extrapolating the results obtained with experimental animal models into the clinical setting. Nevertheless, intratracheal LPS instillation is a widely accepted model to mimic tracheal contamination. Moreover, although the 3-h experimental period is short, it is sufficient to examine the early effects of our ventilatory strategies (8, 18). Animals receiving 7 cmH2O PEEP presented hypercapnia, probably associated with lung overdistension. The brain is sensitive to CO2(35) and we cannot rule out some overlooked effects in this regard. This study provides information about which areas in the brain participate in the response to LPS and PEEP, but it does not explore the mechanisms involved in lung-to-brain communication. The use of vagotomized or haloperidol-treated animals could address the role of vagal signaling in the response to PEEP in future studies (16, 32).

Clinical relevance

Cytokine release has negative effects on emotional and memory functions and can compromise outcomes in critically ill patients (36). Despite the recovery of lung function, survivors of critical disease often fail to recover their previous functional status and have cognitive impairment, memory deficits, or emotional disturbances (9, 36). Brain–lung cross-talk during MV is a novel but growing area of research (7, 8, 16, 32, 37, 38). We can only speculate about how changes in c-fos expression in different areas of the brain could modify susceptibility to long-term neurocognitive disorders. In this regard, the thalamus is involved in processing nociceptive signals and contributes to spatial memory and adaptation to stress (39). The RS is vital for memory, and RS hypoactivity has been reported in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease (39, 40). Both the thalamus and RS are functionally connected with the hippocampus (40), which is involved in forming, organizing, and storing memories and also in connecting emotions and senses to memories.

Characterizing the mechanisms underlying these CNS alterations could help improve strategies to prevent cognitive impairment. Management strategies that contribute to reducing inflammation might somehow help prevent cognitive impairment in intensive care survivors.

CONCLUSIONS

In our experimental model, applying moderate PEEP immediately after intratracheal LPS instillation showed a tendency to prevent lung inflammation, neutrophil recruitment, and the dissemination of inflammatory mediators. Moreover, PEEP modified the neuronal activation pattern in particular areas of the brain, such as the RS, SON, and thalamus. Although neuronal activation in some specific areas might also be explained by the inflammatory response, PEEP might help prevent inflammation by protecting against injury from repeated opening and closing of alveoli.

Cognitive impairment after discharge from intensive care is undoubtedly multifactorial. Our findings show that MV and PEEP level could modulate neuronal activity in some areas in the brain that are related to memory impairment and responses to stress. Further studies are necessary to understand the complex lung-brain interactions in mechanically ventilated patients and to prevent neurocognitive impairment in these patients.

Key messages

PEEP modulates inflammation and the pattern of neuronal activation in the brain.

Lung-brain cross-talk in critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation is clinically relevant and deserves special attention in the intensive care unit.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank John Giba for language revision and Jessica Tijero for technical assistance.

Footnotes

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

JL-A and LB contributed to the conception and design of the study. JL-A, RR-G, MNG, and MEQ were involved in all the experiments and data collection. JL-A and MEQ analyzed and interpreted the data. JCO and JL-A performed the statistical analysis. JL-A and MEQ drafted the manuscript. LB and JL-A coordinated the study and helped to draft the manuscript. MT, SF-G, JV, and RMK critically revised the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Corporative Research Program in Acute Lung Injury from the CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias, FIS PI13/02204 Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain), and I3PT-Fundació Parc Taulí. RR-G is the recipient of a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Contratos postdoctorales de perfeccionamiento en investigación en salud, Programa Sara Borrell CD11/00104).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2001; 344 9:665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 342 18:1334–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villar J, Blanco J, Anon JM, Santos-Bouza A, Blanch L, Ambros A, Gandia F, Carriedo D, Mosteiro F, Basaldua S, et al. The ALIEN study: incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37 12:1932–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead TC, Zhang H, Mullen B, Slutsky AS. Effect of mechanical ventilation on cytokine response to intratracheal lipopolysaccharide. Anesthesiology 2004; 101 1:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chastre J, Fagon JY. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165 7:867–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CY, Zhang H, Cheng KC, Slutsky AS. Mechanical ventilation may increase susceptibility to the development of bacteremia. Crit Care Med 2003; 31 5:1429–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Aguilar J, Fernandez-Gonzalo MS, Turon M, Quilez ME, Gomez-Simon V, Jodar MM, Blanch L. Lung-brain interaction in the mechanically ventilated patient. Med Intensiva 2013; 37 7:485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quilez ME, Fuster G, Villar J, Flores C, Marti-Sistac O, Blanch L, Lopez-Aguilar J. Injurious mechanical ventilation affects neuronal activation in ventilated rats. Crit Care 2011; 15 3:R124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013; 369 14:1306–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turon M, Fernandez-Gonzalo S, Gomez-Simon V, Blanch L, Jodar M. Cognitive stimulation in ICU patients: should we pay more attention? Crit Care 2013; 17 3:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall NG, Liu Y, Hickman-Davis JM, Davis GC, Myles C, Andrews EJ, Matalon S, Lang JD., Jr Bactericidal function of alveolar macrophages in mechanically ventilated rabbits. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006; 34 6:719–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lachmann RA, van Kaam AH, Haitsma JJ, Lachmann B. High positive end-expiratory pressure levels promote bacterial translocation in experimental pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33 10:1800–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy DB, Cregg N, Tremblay L, Engelberts D, Laffey JG, Slutsky AS, Romaschin A, Kavanagh BP. Adverse ventilatory strategy causes pulmonary-to-systemic translocation of endotoxin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162 1:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, Brower RG, Talmor D, Walter SD, Slutsky AS, Pullenayegum E, Zhou Q, Cook D, et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2010; 303 9:865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Lopez A, Garcia-Prieto E, Batalla-Solis E, Amado-Rodriguez L, Avello N, Blanch L, Albaiceta GM. Lung strain and biological response in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38 2:240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Lopez A, Lopez-Alonso I, Aguirre A, Amado-Rodriguez L, Batalla-Solis E, Astudillo A, Tomas-Zapico C, Fueyo A, dos Santos CC, Talbot K, et al. Mechanical ventilation triggers hippocampal apoptosis by vagal and dopaminergic pathways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188 6:693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aleksandrov VG, Mercuriev VA, Ivanova TG, Tarasievich AA, Aleksandrova NP. Cortical control of Hering-Breuer reflexes in anesthetized rats. Eur J Med Res 2009; 14 suppl 4:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Aguilar J, Quilez ME, Marti-Sistac O, Garcia-Martin C, Fuster G, Puig F, Flores C, Villar J, Artigas A, Blanch L. Early physiological and biological features in three animal models of induced acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36 2:347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernooy JH, Dentener MA, van Suylen RJ, Buurman WA, Wouters EF. Long-term intratracheal lipopolysaccharide exposure in mice results in chronic lung inflammation and persistent pathology. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002; 26 1:152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fodor GH, Petak F, Erces D, Balogh AL, Babik B. Lung mechanical changes following bronchoaspiration in a porcine model: differentiation of direct and indirect mechanisms. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2014; 199:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanch L, Fernandez R, Benito S, Mancebo J, Net A. Effect of PEEP on the arterial minus end-tidal carbon dioxide gradient. Chest 1987; 92 3:451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucangelo U, Blanch L. Dead space. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30 4:576–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passaro CP, Silva PL, Rzezinski AF, Abrantes S, Santiago VR, Nardelli L, Santos RS, Barbosa CM, Morales MM, Zin WA, et al. Pulmonary lesion induced by low and high positive end-expiratory pressure levels during protective ventilation in experimental acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2009; 37 3:1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Aguilar J, Lucangelo U, Albaiceta GM, Nahum A, Murias G, Canizares R, Oliva JC, Romero PV, Blanch L. Effects on lung stress of position and different doses of perfluorocarbon in a model of ARDS. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2015; 210C:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods SJ, Waite AA, O’Dea KP, Halford P, Takata M, Wilson MR. Kinetic profiling of in vivo lung cellular inflammatory responses to mechanical ventilation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015; 308 9:L912–L921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinclair SE, Kregenow DA, Lamm WJ, Starr IR, Chi EY, Hlastala MP. Hypercapnic acidosis is protective in an in vivo model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166 3:403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Croinin DF, Hopkins NO, Moore MM, Boylan JF, McLoughlin P, Laffey JG. Hypercapnic acidosis does not modulate the severity of bacterial pneumonia-induced lung injury. Crit Care Med 2005; 33 11:2606–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reyes EP, Abarzua S, Martin A, Rodriguez J, Cortes PP, Fernandez R. LPS-induced c-Fos activation in NTS neurons and plasmatic cortisol increases in septic rats are suppressed by bilateral carotid chemodenervation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 758:185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akrout N, Sharshar T, Annane D. Mechanisms of brain signaling during sepsis. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009; 7 4:296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Gonzalez R, Ramos-Nuez A, Martin-Barrasa JL, Lopez-Aguilar J, Baluja A, Alvarez J, Rocco PR, Pelosi P, Villar J. Endotoxin-induced lung alveolar cell injury causes brain cell damage. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015; 240 1:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mascia L, Grasso S, Fiore T, Bruno F, Berardino M, Ducati A. Cerebro-pulmonary interactions during the application of low levels of positive end-expiratory pressure. Intensive Care Med 2005; 31 3:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.dos Santos CC, Shan Y, Akram A, Slutsky AS, Haitsma JJ. Neuroimmune regulation of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183 4:471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu CL, Li ZP, Zhu JP, Zhao DQ, Ai HB. Studies on functional connections between the supraoptic nucleus and the stomach in rats. J Physiol Sci 2011; 61 3:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Y, Matsuwaki T, Yamanouchi K, Nishihara M. Differential roles of cyclooxygenase-2-related signaling in regulating hypothalamic neuronal activity under various acute stresses. J Vet Med Sci 2014; 76 2:219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brannan S, Liotti M, Egan G, Shade R, Madden L, Robillard R, Abplanalp B, Stofer K, Denton D, Fox PT. Neuroimaging of cerebral activations and deactivations associated with hypercapnia and hunger for air. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98 4:2029–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A, Pollmacher T. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58 5:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Aguilar J, Villagra A, Bernabe F, Murias G, Piacentini E, Real J, Fernandez-Segoviano P, Romero PV, Hotchkiss JR, Blanch L. Massive brain injury enhances lung damage in an isolated lung model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Crit Care Med 2005; 33 5:1077–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quilez ME, Lopez-Aguilar J, Blanch L. Organ crosstalk during acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012; 18 1:23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poirier GL, Amin E, Good MA, Aggleton JP. Early-onset dysfunction of retrosplenial cortex precedes overt amyloid plaque formation in Tg2576 mice. Neuroscience 2011; 174:71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keene CS, Bucci DJ. Involvement of the retrosplenial cortex in processing multiple conditioned stimuli. Behav Neurosci 2008; 122 3:651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.