Abstract

Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors (nAChRs) have potential clinical applications in the treatment of nicotine dependence and many neuropsychiatric conditions associated with decreased brain cholinergic activity, and 3-(2-chlorophenyl)-5-(5-methyl-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrrazol-4-yl)isoxazole (CMPI) has been identified as a PAM selective for neuronal nAChRs containing the α4 subunit. In this report, we compare CMPI interactions with low-sensitivity (α4)3(β2)2 and high-sensitivity (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, and with muscle-type nAChRs. In addition, we use the intrinsic reactivity of [3H]CMPI upon photolysis at 312 nm to identify its binding sites in Torpedo nAChRs. Recording from Xenopus oocytes, we found that CMPI potentiated maximally the responses of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR to 10 μM ACh (EC10) by 400% and with an EC50 of ∼1 µM. CMPI produced a left shift of the ACh concentration-response curve without altering ACh efficacy. In contrast, CMPI inhibited (∼35% at 10 µM) ACh responses of (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs and fully inhibited human muscle and Torpedo nAChRs with IC50 values of ∼0.5 µM. Upon irradiation at 312 nm, [3H]CMPI photoincorporated into each Torpedo [(α1)2β1γδ] nAChR subunit. Sequencing of peptide fragments isolated from [3H]CMPI-photolabeled nAChR subunits established photolabeling of amino acids contributing to the ACh binding sites (αTyr190, αTyr198, γTrp55, γTyr111, γTyr117, δTrp57) that was fully inhibitable by agonist and lower-efficiency, state-dependent [3H]CMPI photolabeling within the ion channel. Our results establish that CMPI is a potent potentiator of nAChRs containing an α4:α4 subunit interface, and that its intrinsic photoreactivy makes it of potential use to identify its binding sites in the (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR.

Introduction

Muscle- and neuronal-type nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels with diverse subunit composition, functions, biophysical properties, and pharmacological characteristics (Jensen et al., 2005; Hurst et al., 2013). Muscle-type nAChRs have a subunit stoichiometry of α2βγδ or α2βεδ, whereas neuronal nAChRs are either homopentamers (e.g., α7 nAChR) or heteropentamers (e.g., α4β2 nAChR) and are expressed pre- and/or postsynaptically at cholinergic and other neurotransmitter synapses (Gotti et al., 2009). Presynaptic neuronal nAChRs are involved in regulation of neurotransmitter release and the modulation of sleep, attention, learning, and memory (Dani and Bertrand, 2007). In addition, neuronal nAChRs play a central role in the development of nicotine addiction and are implicated in the underlying pathology of neuropsychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Jensen et al., 2005).

Drugs that target nAChRs have potential therapeutic uses in the treatment of nicotine addiction and the behavioral symptoms associated with neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions (Taly et al., 2009; Hurst et al., 2013). nAChR positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) are a novel class of cholinergic agents that enhance ACh-mediated responses by binding at site(s) distinct from the conserved ACh (orthosteric) binding sites (Bertrand and Gopalakrishnan, 2007; Williams et al., 2011). nAChR PAMs are characterized by a wide range of chemical structures, and they potentially bind to different sites in an nAChR or selectively to an nAChR subtype (Changeux and Taly, 2008). PAM binding sites in a muscle nAChR have been identified by photoaffinity labeling at subunit interfaces in the transmembrane domain (TMD; Nirthanan et al., 2008) and extracellular domain (ECD; Hamouda et al., 2013). In neuronal nAChRs, mutational analyses identified intersubunit sites in the ECD (Seo et al., 2009; Olsen et al., 2013) and an intrasubunit site in the α7 nAChR TMD (Young et al., 2008; daCosta et al., 2011).

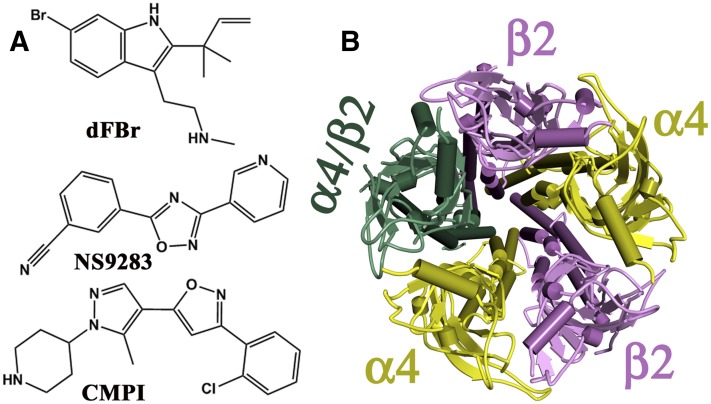

PAMs of the α4β2 nAChR, the most abundant and widely distributed neuronal nAChR subtype, include desformylflustrabromine (dFBr; Sala et al., 2005), 3-(2-chlorophenyl)-5-(5-methyl-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrrazol-4-yl)isoxazole (CMPI; Albrecht et al., 2008), and 3-[3-(pyridin-3-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]benzonitrile (NS9283; Timmermann et al., 2012) (Fig. 1A). dFBr was isolated from the marine bryozoan Flustra foliacea, whereas CMPI and NS9283 were developed through high-throughput screening and lead optimization of chemical libraries. At submicromolar concentrations, dFBr, CMPI, and NS9283 potentiate ACh-induced responses of α4-containing nAChRs but not α3β2 or α7 nAChRs (Sala et al., 2005; Albrecht et al., 2008; Timmermann et al., 2012). Because α4 and β2 subunits are known to assemble in two stoichiometries, 3α4:2β2 and 2α4:3β2 (Fig. 1B), that have distinct pharmacological profiles (Zwart and Vijverberg, 1998; Nelson et al., 2003), the effects of NS9283 and dFBr were examined at both (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs (Timmermann et al., 2012; Weltzin and Schulte, 2015). Whereas dFBr potentiated both α4β2 nAChRs, NS9283 potentiated only (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs by binding to a site at the α4:α4 interface, which is present only in the (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR and overlaps with a third ACh binding site within the ECD (Harpsøe et al., 2011; Mazzaferro et al., 2011; Eaton et al., 2014).

Fig. 1.

(A) The chemical structures of nAChR PAMs: dFBr, NS9283, and CMPI. (B) Top view of a homology model of an α4β2 nAChR containing two α4 and two β2 subunits and a fifth subunit that is either an α4 or β2 subunit. Both (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs have two ACh binding sites within the ECD at the α4:β2 subunit interfaces, and the (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR has a low-affinity ACh binding site within the ECD at the α4:α4 subunit interface.

To further characterize the mode of interaction of CMPI with neuronal and muscle nAChRs, we used a two-electrode voltage-clamp recording from Xenopus laevis oocytes to compare the interactions of CMPI with (α4)3(β2)2, (α4)2(β2)3, and muscle-type nAChRs. We also prepared [3H]CMPI and established that the intrinsic photochemical reactivity of CMPI can be used to identify its binding sites in the ECD and TMD of the muscle-type Torpedo nAChR.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

CMPI was a generous gift from Drs. Stefan McDonough and Alessandro Boezio (Amgen Inc., Cambridge, MA; Albrecht et al., 2008). [3H]CMPI (16 Ci/mmol) was synthesized by custom tritiation (ViTrax, Placentia, CA). dFBr was from Tocris Bioscience R&D (Minneapolis, MN). Acetylcholine chloride, carbamylcholine chloride, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) unless otherwise indicated in the text. Staphylococcus aureus endoproteinase Glu-C (V8 protease) and Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C (EndoLys-C) were from MP Biomedical (Santa Ana, CA) and Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN), respectively. Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes were isolated from freshly dissected Torpedo californica electric organs as described previously (Middleton and Cohen, 1991). Final membranes in 38% sucrose and 0.02% sodium azide were stored at −80°C until the day of use, when they were thawed, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in Torpedo physiologic saline (TPS; 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0).

nAChR Expression in Xenopus Oocytes.

Plasmids with cDNA encoding human α1 (pSPα64T), α4 (pSP64polyA), β1 (pBSII), β2 (pSP64polyA), δ [pBS(SK)], and ε (pBSII) nAChR subunits were provided by Dr. Jon Lindstrom (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). Plasmids with cDNA encoding Torpedo α1, γ, and δ (pMXT) and Torpedo β1 (pSP6) were gifts from Dr. Michael M. White (Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA) and Dr. Henry Lester (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA), respectively. Plasmids were linearized with restriction endonucleases [AseI (hα4) and PvuII (hβ2), BsaAI (Hδ), FspI (hα1 and Tβ), ScaI (Hβ1), XbaI (Tα, Tγ, and Tδ), and XhoI (Hε)], and cRNA transcripts were prepared using SP6 (Torpedo α, β, γ, and δ subunits; human α1, α4, and β2 subunits) or T3 (human β1, δ, and ε subunits) mMESSAGE mMACHINE high yield capped RNA transcription kits (Ambion/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Adult female X. laevis were purchased from NASCO (Fort Atkinson, WI), and ovarian lobules were surgically harvested following animal-use protocols approved by the Texas A&M Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The lobules were treated with 3 mg/ml collagenase type 2 (Worthington Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ) with gentle shaking for 3 hours at room temperature in Ca+2-free OR2 buffer (85 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6). Stage V and VI oocytes were selected, injected with cRNA, and incubated at 18°C in ND96-gentamicin buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 50 µg/ml gentamicin, pH 7.6) for 24–72 hours to allow receptor expression. Oocytes were injected with 100 ng of α4 and β2 cRNA combined at ratios 9α:1β or 1α:9β to express nAChRs with subunit stoichiometries of 3α:2β or 2α:3β, respectively. For Torpedo and human muscle nAChR, oocytes were injected with 20–50 ng of total mRNA mixed at ratios of 2α:1β:1γ:1δ and 2α:1β:1δ:1ε, respectively.

Two-Electrode Voltage-Clamp Recording.

A standard two-electrode voltage-clamp technique was used to study the effects of CMPI and dFBr on ACh-induced current responses of α4β2 and muscle nAChR. Xenopus oocytes were perfused with ND96 recording buffer (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5) and voltage clamped at −50 mV using Oocyte Clamp OC-725B (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Whole-cell currents were digitized using Digidata 1550A/Clampex 10.4 (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices, LLC. Sunnyvale, CA). An automated perfusion system (Warner Instruments) was used to control recording chamber perfusion and drug application. Each recording run included three to six drug applications (10 seconds each) separated by 1- to 4-minute wash intervals. Oocytes were washed with ND96 recording buffer for 3–5 minutes between runs. ACh currents in the absence or presence of CMPI and/or dFBr were quantified using pCLAMP 10.4 (Axon Instruments). For ACh concentration-response curves in the absence or presence of CMPI and/or dFBr, ACh currents were normalized to current elicited by 1000 μM ACh. For calculating the concentration-dependent effects of CMPI and dFBr, ACh currents in the presence of increasing concentrations of CMPI and/or dFBr were normalized to the current elicited by ACh alone. Data (average ± S.E.) of multiple replicas were plotted and fit using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

Radioligand Binding Assays.

The effects of CMPI on the equilibrium binding of agonist ([3H]ACh) and ion-channel blocker ([3H]phencyclidine [PCP]) to Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes in TPS were determined using a centrifugation assay (Hamouda et al., 2011). For [3H]ACh, membranes (40 nM ACh binding sites) were treated for 30 minutes with 0.5 mM diisopropylphosphofluoridate to inhibit acetylcholinesterase and then incubated for 60 minutes with 15 nM [3H]ACh (1.9 Ci/mmol) in the absence of any competitor or in the presence of increasing concentrations of CMPI or 1 mM carbamylcholine (Carb) (to determine nonspecific binding). For [3H]PCP, membranes (0.7 µM ACh binding sites) in TPS were equilibrated with 5 μM α-bungarotoxin (BgTx) or 1 mM Carb to stabilize the nAChR in the resting or desensitized state, respectively, then incubated with 10 nM [3H]PCP (27 Ci/mmol) in the absence or presence CMPI or 100 µM proadifen (to determine nonspecific binding). After incubation at room temperature for 1 hour, the bound and free 3H were separated by centrifugation (18,000g for 1 hour) and quantified in count per minute (cpm) by liquid scintillation counting. For each CMPI concentration, specific 3H binding was calculated (cpmtotal − cpmnonspecific) and normalized to the specifically bound 3H cpm in the absence of competitor. The average ± S.D. of parallel duplicate aliquots was plotted and fit using SigmaPlot (Systat Software).

[3H]CMPI Photolysis and Analytical Photolabeling.

The CMPI UV absorption spectrum was characterized by a peak at 270 nm (extinction coefficient, ε270 = 17,700 M−1 cm−1), whereas ε312 was 600 M−1 cm−1. Using a hand-held lamp (model EB-280C; Spectronics Corp., Westbury, NJ), conditions for photolabeling were determined based upon the observed changes of UV absorption following irradiation of CMPI (20 μM) in TPS at 312 nm, which resulted in a decrease in the 270-nm peak and the formation of a peak at 315 nm with a half-life (t1/2) of 3 minutes. Based upon this result, 3H incorporation into Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes was examined by photolabeling at 312 nm on an analytical scale. Membrane suspensions (2 mg of protein/ml in TPS supplemented with 1 mM oxidized glutathione; 130 µg of protein and 170 pmol ACh binding sites per condition) were equilibrated with 1 μM [3H]CMPI (1 μCi per condition) for 40 minutes at 4°C and then irradiated on ice for 3 or 6 minutes at a distance of less than 1 cm. The membrane polypeptides were then resolved by SDS-PAGE as previously described (Hamouda et al., 2011) on two parallel 8% polyacrylamide gels. Polypeptides were visualized by Coomassie Blue R-250 stain, and one gel was prepared for fluorography using Amplify (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). Polypeptide gel bands were excised from both gels, and 3H incorporation was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Since irradiation for 3 and 6 minutes resulted in the same level of 3H incorporation into nAChR subunits, subsequent analytical and preparative photolabelings were irradiated at 312 nm for 3 minutes.

[3H]CMPI Preparative Photolabeling.

Preparative-scale photolabeling, isolation of photolabeled Torpedo nAChR fragments, and identification of photolabeled amino acids by automated Edman protein microsequencing were performed as detailed previously (Chiara et al., 2009; Hamouda et al., 2013). In brief, Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes (2 mg of protein/ml; 10 mg of protein and ∼13 nmol ACh binding sites per condition) were photolabeled with 1 μM [3H]CMPI (80 μCi per condition) in the absence and presence of 1 mM Carb, and the nAChR subunits were resolved on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel. The nAChR β, γ, and δ subunits were recovered by passive elution from the gel bands excised from the stained gel and resuspended in digestion buffer (15 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.1). The gel bands containing the [3H]CMPI-photolabeled nAChR α subunit were excised and transferred to 15% polyacrylamide mapping gels and subjected to in-gel digestion with 100 μg of V8 protease to generate nAChR α subunit fragments (αV8-20, αV8-18, αV8-10, and αV8-4; Blanton and Cohen 1994) that were recovered from the gel and resuspended in digestion buffer. Greater than 95% of the Carb-inhibitable 3H cpm was recovered in αV8-20, which begins at αSer173 and contains the core aromatics αTyr190 and αTyr198 of ACh binding site segment C and transmembrane helices M1–M3. αV8-20 was digested for 2 weeks with 0.5 units of EndoLys-C, and the digest was then fractionated using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (rpHPLC). All radioactivity in that rpHPLC fractionation eluted as a single, Carb-inhibitable peak centered at ∼80% organic in three fractions which were pooled and loaded onto glass fiber filters for sequencing on a PROCISE 492 protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). At each cycle of Edman degradation, 1/6 was used for amino acid identification/quantification and 5/6 for 3H counting. Photolabeling efficiency (in cpm/pmol) was calculated using the equation [cpmx − cpm(x-1)]/5IoRx, where x is the cycle number, I0 is the initial mass of the peptide sequenced, and R is the repetitive yield of Edman degradation.

[3H]CMPI-photolabeled γ nAChR subunits were digested for 18 hours at room temperature with 200 μg of V8 protease or for 2 weeks with 0.5 units of EndoLys-C. When the V8 digest was fractionated by rpHPLC, the peak of 3H was recovered in fractions centered at ∼40% organic known to contain the γ subunit fragment beginning at γVal102 that contains ACh binding site segment E (γ109 – γ119; Chiara and Cohen, 1997). When the EndoLys-C digest was fractionated by small-pore Tricine-SDS PAGE (Schagger and von Jagow, 1987; Hamouda et al., 2013), the peak of 3H was recovered in a gel band with an apparent molecular mass of ∼24 kDa. When that material was further purified by rpHPLC, all 3H eluted as a broad peak (∼60% organic), which was identified by N-terminal sequencing as the fragment beginning at γGlu47 that contains ACh binding site segment D (γTrp55; Chiara and Cohen, 1997) .

[3H]CMPI-photolabeled nAChR δ subunits were digested for 2 weeks with 0.5 units of EndoLys-C. The digest was fractionated by Tricine SDS-PAGE, and material eluted from gel bands with apparent molecular masses of ∼21 and 14 kDa was fractionated by rpHPLC (Garcia et al., 2007). For the 14-kDa band, the major peak of 3H eluted at ∼70% organic, the region known to contain the fragment beginning at δMet257, the N terminus of the δM2 transmembrane helix (Arevalo et al., 2005). For the 21-kDa band, the major peak of 3H eluted at ∼50% organic and was identified by sequence analysis as the fragment beginning at Glu47 that contains ACh binding site segment D (δTrp57) (Wang et al., 2000).

Data Analyses.

Data analyses and parameter calculations were performed using SigmaPlot version 11 (Systat Software). ACh concentration-response curves in the absence or presence of CMPI and/or dFBr were fit to a three-parameter Hill equation:

| (1) |

where Ix is the current at ACh concentration x, normalized to the current at 1 mM ACh; Imax is the maximum current response; n is the Hill coefficient; and EC50 is the ACh concentration producing 50% of the maximum response.

The concentration-dependent potentiation of ACh-induced currents by CMPI or dFBr was fit to a three-parameter Hill equation:

| (2) |

where Ix is the ACh current in the presence of PAM at concentration x, normalized to the current in the absence (as percentage), Imax is the maximum potentiation of current (as percent control); n is the Hill coefficient; and EC50 is the PAM concentration producing 50% maximal potentiation.

CMPI inhibition of ACh-induced currents in muscle-type nAChRs and CMPI inhibition of [3H]PCP binding to Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes were normalized to their control values in the absence of inhibitor and fit to a single site inhibition model:

| (3) |

where fx is ACh-induced current or specific [3H]PCP binding in the presence of CMPI at concentration x, and IC50 is the CMPI concentration producing 50% inhibition.

Results

CMPI Potentiates Low-Sensitivity (α4)3(β)2 but Not High-Sensitivity (α4)2(β)3 nAChRs.

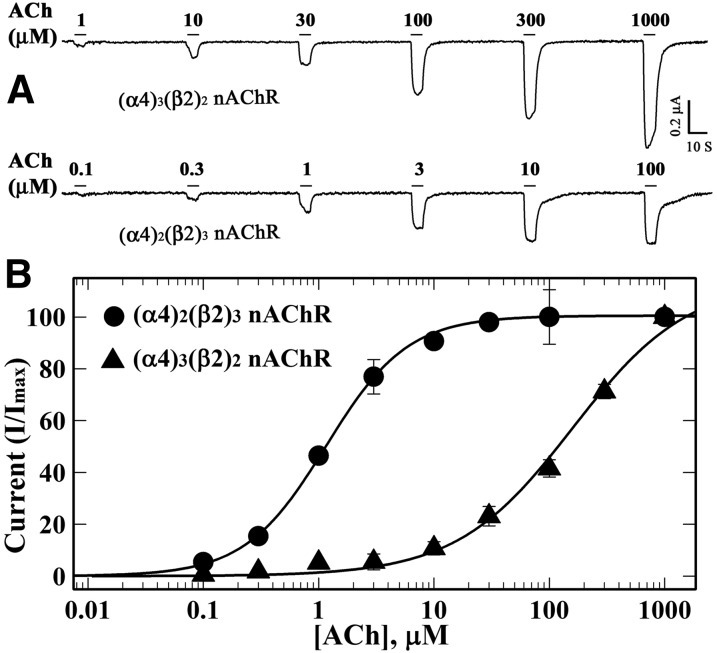

Initial characterization of CMPI as an nAChR PAM established that it potentiated responses of α4β2 nAChRs expressed in human embryonic kidney cells to submaximal doses of nicotine or ACh (Albrecht et al., 2008). To further characterize the pharmacological profile of CMPI at α4β2 nAChRs, we used two-electrode voltage-clamp recording from Xenopus laevis oocytes to characterize the effects of CMPI on the ACh responses of (α4)3(β2)2 (low ACh sensitivity) and (α4)2(β2)3 (high ACh sensitivity) nAChR isoforms. Expression of (α4)3(β2)2 (ACh EC50 = 160 ± 24 μM) and (α4)2(β2)3 (ACh EC50 = 1.14 ± 0.04 μM) nAChRs was achieved by injecting oocytes with a mixture of α4 and β2 mRNAs at ratios of 9α4:1β2 or 1α4:9β2, respectively (Fig. 2). For (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs, CMPI, when coapplied, enhanced the response to 10 µM (EC10) ACh, producing a maximal potentiation (Imax) of 314 ± 17% with an EC50 of 0.26 ± 0.05 µM (Fig. 3, A and C). In oocytes expressing (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, CMPI (0.01–10 µM) did not enhance current responses for 1, 3, or 10 µM ACh. Instead, CMPI reduced the ACh response, maximally by ∼35% at 10 µM CMPI (Fig. 3, B and D). In contrast to the selective potentiation of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs by CMPI, in the same oocytes, dFBr enhanced ACh responses of (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs (Fig. 3, B and F; EC50 = 1.6 ± 0.05 µM; Imax = 304 ± 4%) as well as (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs (Fig. 3E; EC50 = 0.36 ± 0.02 µM; Imax = 417 ± 7%).

Fig. 2.

ACh concentration-response curves of (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs. Xenopus oocytes injected with nAChR subunit mRNAs mixed at a ratio of 9α4:1β2 [▴, (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR] or 1α4:9β2 [⬤, (α4)2(β2)3 nAChR] were voltage clamped at −50 mV, and currents elicited by 10-second applications of increasing concentrations of ACh were recorded. (A) Representative traces of ACh-induced current responses of (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs. For each concentration, the peak currents were normalized to the peak current elicited by 1 mM ACh, and averages (±S.E.) of replicas from multiple oocytes (▴, 4; ⬤, 6) were plotted (B) and fit to a three-parameter Hill equation (Materials and Methods, eq. 1). ACh EC50 values/Hill coefficients for (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs were 160 ± 24 μM/0.9 ± 0.1 and 1.1 ± 0.04 μM/1.2±0.04, respectively.

Fig. 3.

CMPI potentiates low-sensitivity (α4)3(β2)2 but not high-sensitivity (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs. Xenopus oocytes expressing human (α4)3(β2)2 (▴) or (α4)2(β2)3 (⬤, ○) nAChRs were voltage clamped at −50 mV, and currents elicited by 10-second applications of 10 µM ACh (⬤, ▴) or 3 µM ACh (○) were recorded in the absence or presence of CMPI (A–D) or dFBr (E and F). Shown in (A and B) are representative traces of the effects of CMPI on ACh-induced current responses of (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, respectively. (C–F) At each PAM concentration, the current response was normalized to the current elicited by ACh alone, and the average ± S.E. of responses from multiple oocytes [11 (C); 3 (⬤), 4 (○) (D); 14 (E); 5 (F)] is plotted. Potentiation data (C, E, and F) were fit to a three-parameter equation (eq. 2). Inhibition data (D) were fit to a single site model of inhibition (eq. 3). (C) The concentration dependence of CMPI potentiation of the (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR was characterized by EC50 = 0.26 ± 0.05 µM, n = 1.2 ± 0.2, and Imax = 314 ± 17%. CMPI also potentiated responses of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR to 1 µM ACh (three oocytes; data not shown) with EC50 = 0.4 ± 0.03 µM, n = 1.4 ± 0.2, and Imax = 238 ± 8%. (D) CMPI at 10 µM inhibited (α4)2(β2)3 nAChR by 39 ± 3% with IC50 = 0.6 ± 0.2 µM. (E) dFBr potentiation of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs was characterized by EC50 = 0.36 ± 0.02 µM, n = 1.6 ± 0.2, and Imax = 417 ± 7%. (F) dFBr potentiation of (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs was characterized by EC50 = 1.6 ± 0.04 µM, n = 1.2 ± 0.03, and Imax = 304 ± 4%.

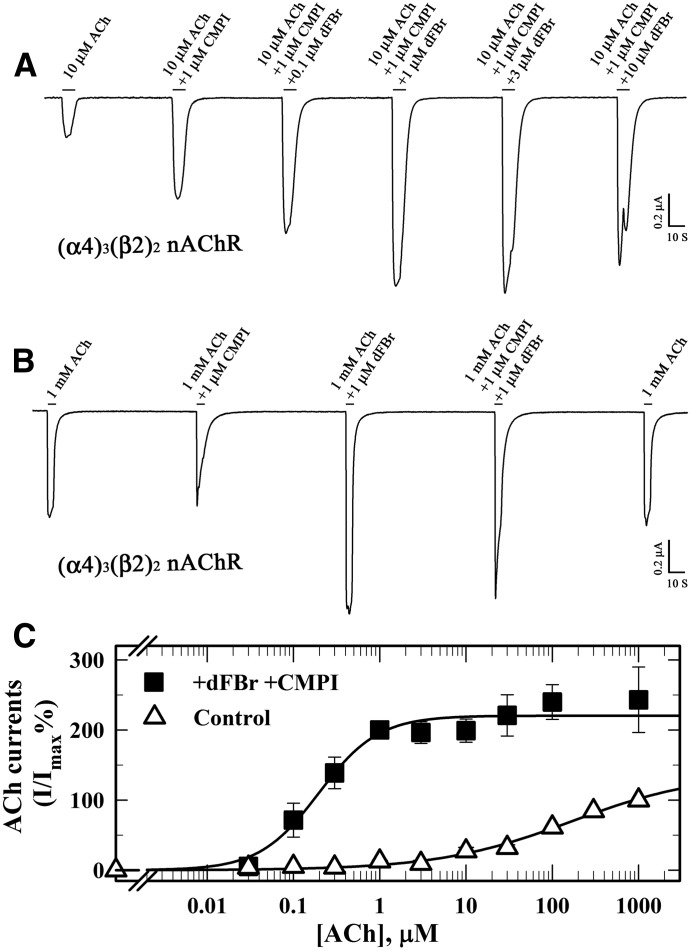

When coapplied with ACh to oocytes expressing (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs, CMPI at 1 µM produced a left shift of the ACh concentration response, decreasing EC50 from 92 ±17 µM to 0.7±0.2 μM without any change in the maximum response (Imax = 97 ± 4%) (Fig. 4, A and B). This effect of CMPI on the ACh concentration response is similar to that of NS9283 (Olsen et al., 2013) but differs from that of dFBr, which potentiated responses for 1 mM ACh (Fig. 4C) with an EC50 of ∼0.3 µM, i.e., a value similar to that seen for 10 µM ACh (Fig. 3E). dFBr increased the ACh maximal response (Imax = 339 ± 52%) with little effect on ACh potency (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

CMPI increases ACh potency at low sensitivity (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs. ACh current responses of Xenopus oocytes expressing (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR were recorded in the absence of any other drug (△) and in the presence of 1 µM CMPI or 1 µM dFBr. (A) A representative current trace showing the effect of 1 µM CMPI on currents elicited by 10, 100, and 1000 µM ACh. (B) ACh concentration-response curves for (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs in the absence (△) and presence of 1 µM CMPI (▴). (C) A representative current trace showing the effect of increasing concentrations of dFBr on currents elicited by 1000 µM ACh. (D) ACh concentration-response curves for (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs in the absence (△) and presence of 1µM dFBr (▴). For each ACh concentration (−/+ drug), the current was normalized to the current elicited by 1000 µM ACh in the same oocyte. Averages (±S.E.) for responses from multiple oocytes [14 (△), 12 (▴) (B); 6 (△), 4 (▴)] were plotted and fit to eq. 1. Values of ACh (EC50/n/Imax) were as follows: ACh (control), 92 ± 17 μM/0.8 ± 0.07/110 ± 6%; ACh (+CMPI), 0.7 ± 0.2 μM/0.6 ± 0.1/97 ± 4% (B); ACh (control), 190 ± 30 μM/0.73 ± 0.04/130 ± 6%; ACh (+1 dFBr), 139 ± 112 μM/0.43 ± 0.06/339 ± 52% (D). For high-sensitivity (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs (not shown), the effect of dFBr on the ACh concentration response was characterized by ACh EC50/n/Imax values of 1.4 ± 0.08 μM/1.2 ± 0.08/111 ± 1.4% (−dFBr) and 2.3 ± 0.05 μM/0.8 ± 0.1/464 ± 23% (+dFBr).

The differences between CMPI and dFBr in terms of α4β2 nAChR isoform selectivity and their effects on the ACh responses led us to examine the effect of CMPI on (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR potentiation by dFBr and vice versa. In the presence of 1 µM CMPI, a concentration that alone elicited maximum potentiation of the ACh response at submaximal concentrations, dFBr still produced a further potentiation of ACh at 10 µM (EC10; Fig. 5A) or at 1 mM (Fig. 5B). Simultaneous application of 1 µM CMPI and 1 µM dFBr produced a left shift in the ACh concentration-response curve, increasing ACh potency by ∼100-fold and increasing efficacy (Imax = 223 ± 8%) (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that CMPI and dFBr bind at different sites and act independently to enhance the potency or efficacy of ACh at (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs.

Fig. 5.

CMPI and dFBr act independently to potentiate low-sensitivity (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs. (A and B) Representative current responses elicited by 10 µM ACh (A) or 1000 µM ACh (B) in the absence and presence of CMPI and/or dFBr. (C) ACh concentration response in the absence (△) and presence of 1 µM CMPI and 1 µM dFBr (▪). For each ACh concentration (−/+ drug), the current was normalized to the current elicited by 1000 µM ACh in the same oocyte. Average (±S.E.) from multiple oocytes [△ (9), ▪ (8)] were plotted and fit to eq. 1. Values of ACh (EC50/n/Imax) were as follows: ACh (control), 106 ± 29 μM/0.62 ± 0.06/124 ± 7%; ACh (+CMPI+dFBr), 0.20 ± 0.04 μM/1.2 ± 0.3/223 ± 8%.

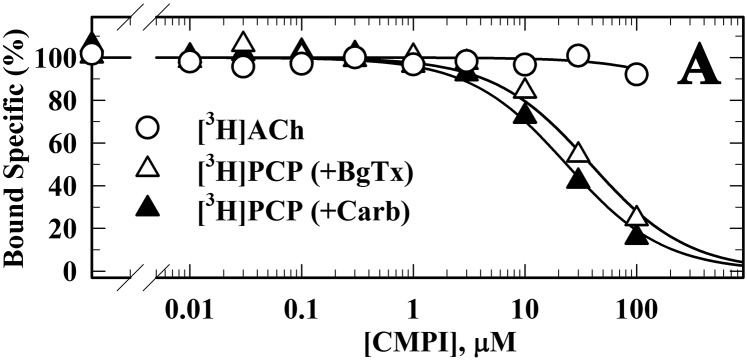

CMPI Is an Inhibitor of Muscle-Type nAChRs.

Because the interaction of CMPI with muscle-type nAChRs has not been characterized, we examined the effect of CMPI on ACh-induced currents in Xenopus oocytes expressing human muscle (2α:1β:1δ:1ε) or Torpedo (2α:1β:1γ:1δ) nAChRs (Fig. 6). CMPI inhibited human muscle and Torpedo nAChRs with IC50 values of 0.7 ± 0.05 and 0.2 ± 0.03 µM, respectively. Additionally, we characterized the effect of CMPI on the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh and an ion-channel blocker ([3H]PCP) to Torpedo nAChR (Fig. 7). CMPI up to 100 µM did not displace [3H]ACh binding. However, CMPI competitively inhibited [3H]PCP binding to Torpedo nAChR stabilized either in the resting state, closed-channel state (+BgTx, IC50 = 20 µM), or desensitized state (+Carb, IC50 = 35 µM). These results indicate that CMPI, at concentrations that produced functional inhibition of muscle-type nAChRs, binds to a site within the ion channel but not to the orthosteric ACh binding sites.

Fig. 6.

CMPI inhibits muscle-type nAChRs. Xenopus oocytes injected with mRNA for human muscle (2α:1β:1δ:1ε; ▽) or Torpedo (2α:1β:1γ:1δ; ▴) nAChR were voltage clamped at −50 mV, and currents elicited by 10-second applications of 10 µM ACh were recorded in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of CMPI. Shown in (A) and (B) are representative traces for human α2β1εδ and Torpedo α2β1γδ nAChRs. (C) Currents were normalized to the peak current elicited by 10 µM ACh alone, and averages (±S.E.) of multiple replicas from six oocytes were plotted and fit to a single site inhibition model (eq. 3). CMPI inhibited human muscle and Torpedo nAChR with IC50 values of 0.7 ± 0.05 and 0.2 ± 0.03 µM, respectively.

Fig. 7.

CMPI binds in the Torpedo nAChR ion channel. Equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh and [3H]PCP to Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes was determined in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of CMPI. Specific binding was calculated as the difference between the total and nonspecific binding, which was determined in the presence of 1 mM Carb ([3H]ACh) or 100 μM proadifen ([3H]PCP), and then normalized to the specific binding in the absence of CMPI. Data were fit to a single site model of inhibition (eq. 3). Binding (total/nonspecific) was as follows: for [3H]ACh (−/+1 mM Carb, 10,680 ± 65/130 ± 3 cpm); for [3H]PCP (+Carb, −/+100 µM proadifen, 7640 ± 75/1580 ± 15 cpm; +BgTx, −/+100 µM proadifen, 4240 ± 47/1933 ± 22 cpm). CMPI inhibited [3H]PCP binding in the presence of Carb or BgTx with IC50 values of 20 ± 1 µM and 35±3 µM, respectively.

Photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR with [3H]CMPI.

UV photolysis conditions for optimal [3H]CMPI photoincorporation into Torpedo nAChR subunits were established as described in Materials and Methods. To examine the pharmacological specificity of [3H]CMPI photoincorporation into the nAChR, Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes were photolabeled with [3H]CMPI (1 μM) in the absence (no drug added) and presence of 1 mM Carb, 2 µM BgTx, or 100 µM CMPI, and covalent incorporation within the subunits was determined by SDS-PAGE followed by fluorography or liquid scintillation counting (Fig. 8). In the absence of any other drug, [3H]CMPI photoincorporated most prominently into the nAChR α, β, and γ subunits and into non-nAChR proteins that bind to the nAChR (Rn, rapsyn) or are present in contaminating membrane fragments [calelectrin (37K), a member of the annexin family of Ca2+-binding proteins, and the α subunit of Na+/K+-ATPase (90K)] (Blanton et al., 2001). Photolabeling of α and γ nAChR subunits was reduced by the same extent (∼50%) in the presence of Carb, BgTx, or CMPI, indicating that a major component of subunit photolabeling was likely to be within the amino acids contributing to the ACh binding site at the α:γ subunit interface. Photolabeling in the nAChR δ subunit, which contributes to the ACh binding site at the α:δ subunit interface, was ∼30% that of the γ subunit and was decreased by ∼10 and 20% in the presence of BgTx and CMPI, respectively.

Fig. 8.

Photoincorporation of [3H]CMPI into Torpedo nAChR–rich membranes. (A) Coomassie Blue stain (lane 1) and fluorograph (lanes 2–3) of an SDS-PAGE gel for membranes (130 µg, 170 pmol ACh sites per condition) photolabeled with 1 µM [3H]CMPI in the absence of other ligand (lane 2) or in the presence of 1 mM Carb (lane 3). The electrophoretic mobilities of the nAChR α, β, γ, and δ subunits; rapsyn (Rn); the Na+/K+-ATPase α subunit (90K); and calelectrin (37K) are indicated. (B) Quantification of the effects of Carb, BgTx, and CMPI (100 µM) on [3H]CMPI incorporation into nAChR subunits. Data in (B) are from the same analytical [3H]CMPI photolabeling experiment, with photolabeling in the control condition (no drug added) done in duplicate. Aliquots of nAChRs from each photolabeling condition were resolved on two parallel SDS-PAGE gels, and polypeptide bands were excised from both gels for 3H quantification by liquid scintillation counting. Data for Carb, BgTx, and CMPI conditions are average ± 1/2 range of gel bands excised from the two parallel gels. Data for the control condition are average ± S.D. of four gel bands from the two parallel gels.

[3H]CMPI Photolabeling of Agonist Binding Sites.

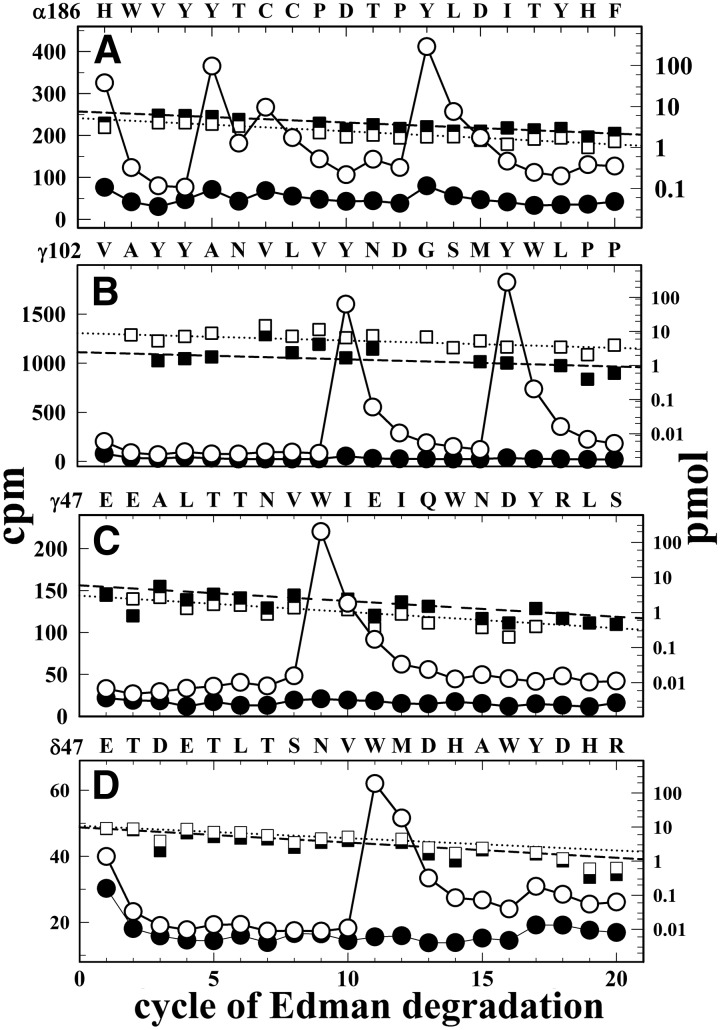

The ACh binding sites of the muscle-type nAChR are located within the ECD at the two α subunit interfaces with adjacent γ and δ subunits. Core aromatic residues contributing to the ACh binding sites are located in three distinct regions within the primary sequence of the α subunit (segments A, B, and C) that contribute to the principal surface of the binding pocket, and amino acids that contribute to the complementary surface are located in three regions within the γ or δ subunits (segments D, E, and F) (Brejc at al. 2001; Changeux and Taly, 2008). To identify amino acids photolabeled within the α subunit, the [3H]CMPI-photolabeled α subunit was subjected to in-gel digestion with V8 protease (data not shown). The majority (>95%) of Carb-inhibitable 3H was contained with αV8-20, which begins at αSer173 and contains the core aromatics in ACh binding site segment C (αTyr190/αTyr198) and transmembrane helices M1–M3. When the subunit fragment beginning at αHis186 was isolated from an EndoLys-C digest of αV8-20 and sequenced (Fig. 9A), the peaks of 3H release in cycles 5, 7, and 13 indicated [3H]CMPI photolabeling of αTyr190, αCys192, and αTyr198 (16, 8, and 29 cpm/pmol, respectively), which was inhibited by >90% in the presence of Carb. To identify amino acids photolabeled within γ subunit ACh binding site segments D (core aromatic γTrp55) and E (γ109-γ119), peptides beginning at γGlu47 and γVal102 were isolated from EndoLys-C and V8 protease digests of γ subunit, respectively. Sequencing of the peptide beginning at γVal102 established [3H]CMPI photolabeling of γTyr111 (56 cpm/pmol) and γTyr117 (84 cpm/pmol) that was completely inhibitable by Carb (Fig. 9B). Amino acid sequencing of a peptide beginning at γGlu47 (Fig. 9C) identified Carb-inhibitable photolabeling of γTrp55 (−/+Carb, 30/0.7 cpm/pmol). Sequencing of a peptide beginning at δGlu47 that contains δ subunit ACh binding site segment D (core aromatic δTrp57) (Fig. 9D) established that there was also Carb-inhibitable photolabeling of δTrp57 (−/+Carb, 2/0.1 cpm/pmol), but it was at less than 10% the efficiency of photolabeling of γTrp55, the corresponding amino acid in γ subunit ACh binding site segment D.

Fig. 9.

[3H]CMPI photolabeling of ACh binding sites. 3H (○, ⬤) and phenylthiohydantoin amino acids (⬜, ▪) released during sequence analyses of nAChR subunit fragments beginning at αHis186 containing segment C of the ACh binding sites (ABS) (A), γVal102 containing ACh binding site segment E (B), and γGlu47 and δGlu47 containing ACh binding site segment D (C and D). The fragments were isolated from Torpedo nAChR photolabeled with [3H]CMPI in the absence (⬜, ○) and presence of Carb (▪,⬤), as described under Materials and Methods. (A) The fragment beginning at αHis186 (⬜,−Carb/▪, +Carb, 5.2/7.5 pmol) was present at a 10-fold higher level than any other fragment, and the Carb-inhibitable peaks of 3H release at cycles 5, 7, and 13 established photolabeling of αTyr190 and αTyr198, the core aromatics in α subunit ACh binding site segment C, at 16 and 29 cpm/pmol, respectively, and of αCys192 at 8 cpm/pmol. (B) The fragment beginning at γVal102 was present (⬜, −Carb/▪, +Carb, 9/2.5 pmol) as a secondary sequence along with an N-terminal fragment of V8 protease (Val1; −Carb/+Carb, 200/140 pmol). The major peaks of 3H release at cycles 10 and 16 established Carb-inhibitable photolabeling of γTyr111 and γTyr117 at 56 and 82 cpm/pmol, respectively. (C) With the fragment beginning at γGlu47 (⬜,−Carb/▪, +Carb, 3/6 pmol) present at a 10-fold higher level than any other fragment, the peak of 3H release at cycle 9 indicates photolabeling of the core aromatic in γ subunit ACh binding sites segment D, γTrp55 (○, −Carb/⬤, +Carb, 30/0.7 cpm/pmol). (D) Fragments beginning at δGlu47 and δHis26 were present (⬜, −Carb/▪, +Carb, 11/10 and 3/2.6 pmol, respectively). The peak of 3H release at cycle 11 was consistent with Carb-inhibitable photolabeling of the core aromatic in δ subunit ACh binding site segment D, δTrp57 (○, −Carb/⬤, +Carb, 2/0.1 cpm/pmol).

CMPI Photolabeling of the Ion Channel.

While the majority of [3H]CMPI photoincorporation was associated with the ACh binding sites, CMPI inhibition of [3H]PCP and [3H]ACh binding to the Torpedo nAChR established that CMPI binds with higher affinity in the ion channel than in the ACh binding sites. To identify the CMPI binding site within the ion channel, we examined [3H]CMPI photolabeling of amino acid residues within the M2 helices that line the ion channel (Unwin, 2005). As shown in Fig. 10, N-terminal sequencing of a subunit fragment beginning at the N terminus of δM2 (δMet257) established state-dependent photolabeling of residues known to line the ion channel lumen. For nAChRs photolabeled with [3H]CMPI in the absence of Carb (resting state), there was a peak of 3H release in cycle 13 that indicated labeling of δVal271 (δM2-13; 0.6 cpm/pmol). In the presence of Carb (desensitized state), photolabeling of δVal271 was reduced by 75%. The major peak of 3H release was in cycle 6, indicating photolabeling of δSer262 (δM2-6; 0.3 cpm/pmol).

Fig. 10.

[3H]CMPI photolabeling in the Torpedo nAChR (δM2) ion channel. 3H (○, ⬤) and phenylthiohydantoin amino acids (⬜, ▪) released during sequence analyses of the δ subunit fragment beginning at δMet257 (−/+Carb, 19/11 pmol) isolated from nAChRs photolabled by [3H]CMPI in the absence (−Carb; ○, ⬜) or presence (+Carb; ⬤, ▪) of 1 mM Carb. For the –Carb condition, the peak of 3H release in cycle 13 indicates photolabeling of δVal271 (δM2-13; 0.6 cpm/pmol) that was inhibited by 76% in the presence of Carb. For the +Carb condition, the peak of 3H release in cycle 6 indicates [3H]CMPI photolabeling at δSer262 (δM2-6; 0.3 cpm/pmol).

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that CMPI, a potent PAM selective for nAChRs containing the α4 subunit (Albrecht et al., 2008), potentiates responses of (α4)3(β2)2 (low-sensitivity) nAChRs, but not (α4)2(β2)3 (high-sensitivity) nAChRs. By recording from Xenopus oocytes expressing (α4)3(β2)2, (α4)2(β2)3, or muscle-type (α2βεδ or α2βγδ) nAChRs, we found that CMPI enhances ACh potency of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs without changing ACh efficacy (maximal response). At concentrations producing a maximal enhancement of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR responses, CMPI acts as an allosteric inhibitor of (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs and of human (α2βεδ) and Torpedo (α2βγδ) muscle-type nAChRs. In the Torpedo nAChR, CMPI binds with >30-fold higher affinity in the ion channel than in the agonist binding sites. Identification of the Torpedo nAChR amino acids photolabeled by [3H]CMPI confirmed binding in the ion channel and the ACh binding sites, and no evidence was found of photolabeling of other sites in the nAChR ECD or TMD. However, the fact that CMPI photoincorporated into valine and serine side chains in the ion channel and into tyrosines and tryptophans in the ACh binding sites demonstrates that CMPI is a photoreactive PAM possessing broad amino acid side-chain reactivity, which makes it well suited to identify PAM binding sites in neuronal nAChRs.

Pharmacology of CMPI at α4β2 nAChRs.

The selective potentiation of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs indicates that the α4:α4 interface is required for CMPI binding and/or modulation of channel gating. In addition to CMPI, physostigmine (a nonselective nAChR PAM) and NS9283 [a PAM selective for nAChRs containing α2 and α4 subunits (Timmermann et al., 2012)] also require the presence of an α4:α4 subunit interface for α4β2 nAChR potentiation (Olsen et al., 2013, 2014; Jin et al., 2014). Although there is no established relationship between the location of a PAM binding site and its effect on ACh responses, these nAChR PAMs with α4:α4 subunit interface selectivity each increase ACh potency without altering the ACh maximal response (Pandya and Yakel, 2011; Olsen et al., 2013), similar to the effect of benzodiazepines on GABA responses in αβγ GABA type A receptors (Sigel and Steinmann, 2012).

In contrast, consistent with previous results (Kim et al., 2007; Weltzin and Schulte, 2015), we found that dFBr potentiates both (α4)3(β2)2 and (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, increasing ACh maximal responses with little effect on ACh EC50. We also found that CMPI at 1 µM, a concentration that produces maximal potentiation, did not prevent further potentiation of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR by dFBr and vice versa (Fig. 5, A and B). The effects of both CMPI (decreased ACh EC50) and dFBr (increased ACh maximal response) were maintained when CMPI and dFBr were coapplied with ACh (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that CMPI and dFBr potentiate (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR by independent mechanisms. They also establish the presence of at least two classes of PAM binding sites within α4β2 nAChRs: one at the α4:α4 subunit interface that mediates potentiation by CMPI, and one or more at the α4:β2 and/or β2:α4 subunit interface that mediate potentiation by dFBr. In α4β2 nAChRs, there can be a single binding site per receptor for PAMs such as CMPI and NS9283, which are selective for (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs and bind at the α4-α4 subunit interface. For NS9283, mutational analyses predicted a binding site in the ECD at the α4:α4 subunit interface that overlaps with the third ACh binding site in that receptor (Olsen et al., 2013). However, further studies will be required to determine whether, in the (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR, CMPI binds to the same site as NS9283. For PAMs such as dFBr that potentiate (α4)2(β2)3 and (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs, there will be at least two binding sites within a receptor, either at subunit interfaces (intersubunit sites) or within a subunit’s helix bundle (intrasubunit sites). In agreement with this, substitutions of an amino acid within the β subunit ECD that projects into the β-α interface (two per receptor) reduced α4β2 nAChR potentiation by dFBr (Weltzin and Schulte, 2015).

[3H]CMPI Is an nAChR Photoreactive Probe.

Photoaffinity labeling and protein microsequencing techniques have been used extensively for identification of amino acids contributing to drug binding sites in many targets (Vodovozova, 2007; Das, 2011), including muscle-type nAChR binding sites for orthosteric ligands, channel blockers, and allosteric modulators (Hamouda et al., 2014; Forman et al., 2015). Photoaffinity labeling identifies amino acid residues within the protein structure that are in direct contact with a bound drug and differentiates them from amino acids not contributing to the binding site but important for drug action, which can be identified by mutational analyses. Even though CMPI bound with >30-fold higher affinity in the Torpedo nAChR ion channel than in the transmitter binding sites, [3H]CMPI photoincorporated with >3-fold higher efficiency into γTrp55, γTyr111, and γTyr117 in the ACh binding sites than into δVal271, the amino acid labeled most efficiently in the ion channel (Fig. 11). Since reaction with aromatic amino acid side chains is likely to occur by a different reactive intermediate than incorporation into aliphatic amino acid side chains, this result is not unexpected. However, the fact that [3H]CMPI incorporates into γTrp55 with 15-fold higher efficiency than into δTrp57, the amino acid in δ subunit ACh binding site segment D equivalent to γTrp55 in the γ subunit, suggests that CMPI binds preferentially to the ACh binding site at the α-γ interface, as is seen for d-tubocurarine, the classic muscle-type nAChR competitive antagonist, which photolabels the same amino acids in the ACh binding site as CMPI (Chiara and Cohen, 1997; Chiara et al., 1999).

Fig. 11.

Location of [3H]CMPI-photolabeled amino acids within the Torpedo nAChR ECD and TMD. Side views of the Torpedo nAChR (Unwin, 2005; α, gold; β, cyan; γ, green; and δ, brown) from the outside showing the ECD of α-γ subunits (A) and from the inside of the ion channel showing the TMD of the β-δ-α subunits (B). [3H]CMPI-photolabeled amino acids within the ACh binding site at the extracellular interface of α:γ subunits and within the δM2 helix that contribute to the ion channel are shown in stick format and colored by elements (carbone, gray; oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue).

As seen for ACh binding site photolabeling by [3H]d-tubocurarine and other photoaffinity agonists and competitive antagonists, [3H]CMPI photolabeling of the ACh binding site core aromatics (αTyr190, αTyr198, γTrp55, and δTrp57) and of γTyr111 and γTyr117 was fully inhibited in the presence of agonist (Chiara and Cohen, 1997; Nirthanan et al., 2005; Srivastava et al., 2009). This full inhibition of photolabeling by agonist contrasts with what has been seen for [3H]dFBr and the nonselective nAChR PAMs [3H]physostigmine and [3H]galanthamine, which also photolabeled amino acids at the α/γ extracellular subunit interface (αTyr190, αTyr198, γTyr111, and γTyr117) but with different Carb sensitivity (Hamouda et al., 2013, 2015). [3H]dFBr, [3H]physostigmine, and [3H]galanthamine still photolabeled γTyr111/γTyr117 in the presence of Carb, which demonstrated the presence of a binding site for these PAMs in the presence of agonist at the entry to the agonist site. In addition, they also photolabeled γTyr105, identifying a binding site for dFBr/physostigmine/galanthamine in the vestibule of the ion channel. Carb completely inhibited [3H]CMPI binding in proximity to γTyr111/γTyr117, and [3H]CMPI did not photolabel γTyr105, which indicates that CMPI does not bind to the dFBr/physostigmine/galanthamine allosteric sites in the ECD at the α/γ subunit interface near the entry of the ACh binding site or in the vestibule of the ion channel.

Our results establish that CMPI is a PAM that can photoincorporate into aliphatic as well as nucleophilic amino acid side chains, but we can only speculate on the photoreactive intermediates formed upon irradiation at 312 nm. CMPI has a complex ring structure (Fig. 1) containing piperidine, chlorobenzene, and pyrazole isoxazole rings. CMPI photoincorporation into valine in the ion channel indicates the likely involvement of a radical intermediate, whereas reactions with serines or aromatic amino acid side chains can occur via radical or electrophilic intermediates. The 3,5-disubstituted isoxazole ring forms a reactive azirine intermediate upon irradiation at 313 nm or shorter wavelengths (Price and Ratajczak, 1984), and UV irradiation of pyrazoles at wavelengths below 250 nm results in H-atom loss and formation of radical intermediates (King et al., 2010). Similarly, photodehalogenation (C-Cl cleavage) of the chlorobenzene ring would form a radical intermediate with broad amino acid side-chain reactivity. Even in the absence of further definition of CMPI’s photoreactive intermediates, the fact that it photoincorporates into a broad range of amino acid side chains makes it well suited for use in the identification of its binding sites in (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs, where it acts as a PAM, and in (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, where it acts as a negative allosteric modulator.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stefan I. McDonough and Dr. Alessandro A. Boezio from Amgen Inc. for generously providing CMPI.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- BgTx

α-bungarotoxin

- Carb

carbamylcholine

- CMPI

3-(2-chlorophenyl)-5-(5-methyl-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrrazol-4-yl)isoxazole

- cpm

count per minute

- dFBr

desformylflustrabromine

- ECD

extracellular domain

- EndoLys-C

Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- NS9283

3-[3-(pyridin-3-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]benzonitrile

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PCP

phencyclidine

- rpHPLC

reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- TPS

Torpedo physiologic saline

- V8 protease

Staphylococcus aureus endoproteinase Glu-C

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Hamouda, Cohen.

Conducted experiments: Hamouda, Deba, Wang.

Performed data analysis: Hamouda, Deba, Cohen.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hamouda, Cohen.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by the Edward and Anne Lefler Center of Harvard Medical School (J.B.C.), Faculty Development Fund of Texas A&M Health Sciences Center (A.K.H.), and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke [Grant NS-093590] (A.K.H).

References

- Albrecht BK, Berry V, Boezio AA, Cao L, Clarkin K, Guo W, Harmange JC, Hierl M, Huang L, Janosky B, et al. (2008) Discovery and optimization of substituted piperidines as potent, selective, CNS-penetrant alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor potentiators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 18:5209–5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo E, Chiara DC, Forman SA, Cohen JB, Miller KW. (2005) Gating-enhanced accessibility of hydrophobic sites within the transmembrane region of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor’s δ-subunit. A time-resolved photolabeling study. J Biol Chem 280:13631–13640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Gopalakrishnan M. (2007) Allosteric modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 74:1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MP, Cohen JB. (1994) Identifying the lipid-protein interface of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: secondary structure implications. Biochemistry 33:2859–2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MP, Lala AK, Cohen JB. (2001) Identification and characterization of membrane-associated polypeptides in Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-rich membranes by hydrophobic photolabeling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1512:215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M, van Der Oost J, Smit AB, Sixma TK. (2001) Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 411:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP, Taly A. (2008) Nicotinic receptors, allosteric proteins and medicine. Trends Mol Med 14:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Cohen JB. (1997) Identification of amino acids contributing to high and low affinity d-tubocurarine sites in the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem 272:32940–32950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Hamouda AK, Ziebell MR, Mejia LA, Garcia G, 3rd, Cohen JB. (2009) [(3)H]chlorpromazine photolabeling of the torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor identifies two state-dependent binding sites in the ion channel. Biochemistry 48:10066–10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Xie Y, Cohen JB. (1999) Structure of the agonist-binding sites of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: affinity-labeling and mutational analyses identify gamma Tyr-111/delta Arg-113 as antagonist affinity determinants. Biochemistry 38:6689–6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- daCosta CJB, Free CR, Corradi J, Bouzat C, Sine SM. (2011) Single-channel and structural foundations of neuronal α7 acetylcholine receptor potentiation. J Neurosci 31:13870–13879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D. (2007) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:699–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J. (2011) Aliphatic diazirines as photoaffinity probes for proteins: recent developments. Chem Rev 111:4405–4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JB, Lucero LM, Stratton H, Chang Y, Cooper JF, Lindstrom JM, Lukas RJ, Whiteaker P. (2014) The unique α4+/-α4 agonist binding site in (α4)3(β2)2 subtype nicotinic acetylcholine receptors permits differential agonist desensitization pharmacology versus the (α4)2(β2)3 subtype. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 348:46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SA, Chiara DC, Miller KW. (2015) Anesthetics target interfacial transmembrane sites in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 96 (Pt B):169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, 3rd, Chiara DC, Nirthanan S, Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Cohen JB. (2007) [3H]Benzophenone photolabeling identifies state-dependent changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor structure. Biochemistry 46:10296–10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Clementi F, Fornari A, Gaimarri A, Guiducci S, Manfredi I, Moretti M, Pedrazzi P, Pucci L, Zoli M. (2009) Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 78:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Kimm T, Cohen JB. (2013) Physostigmine and galanthamine bind in the presence of agonist at the canonical and noncanonical subunit interfaces of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Neurosci 33:485–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Jayakar SS, Chiara DC, Cohen JB. (2014) Photoaffinity labeling of nicotinic receptors: diversity of drug binding sites! J Mol Neurosci 53:480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Husain SS, Cohen JB. (2011) Multiple transmembrane binding sites for p-trifluoromethyldiazirinyl-etomidate, a photoreactive Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric inhibitor. J Biol Chem 286:20466–20477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Wang Z-J, Stewart DS, Jain AD, Glennon RA, Cohen JB. (2015) Desformylflustrabromine (dFBr) and [3H]dFBr-Labeled Binding Sites in a Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Mol Pharmacol 88:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpsøe K, Ahring PK, Christensen JK, Jensen ML, Peters D, Balle T. (2011) Unraveling the high- and low-sensitivity agonist responses of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 31:10759–10766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst R, Rollema H, Bertrand D. (2013) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from basic science to therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther 137:22–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AA, Frølund B, Liljefors T, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. (2005) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. J Med Chem 48:4705–4745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Bermudez I, Steinbach JH. (2014) The nicotinic α5 subunit can replace either an acetylcholine-binding or nonbinding subunit in the α4β2* neuronal nicotinic receptor. Mol Pharmacol 85:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Padnya A, Weltzin M, Edmonds BW, Schulte MK, Glennon RA. (2007) Synthesis of desformylflustrabromine and its evaluation as an alpha4beta2 and alpha7 nACh receptor modulator. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17:4855–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GA, Oliver TA, Nix MG, Ashfold MN. (2010) Exploring the mechanisms of H atom loss in simple azoles: Ultraviolet photolysis of pyrazole and triazole. J Chem Phys 132:064305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro S, Benallegue N, Carbone A, Gasparri F, Vijayan R, Biggin PC, Moroni M, Bermudez I. (2011) Additional acetylcholine (ACh) binding site at alpha4/alpha4 interface of (alpha4beta2)2alpha4 nicotinic receptor influences agonist sensitivity. J Biol Chem 286:31043–31054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton RE, Cohen JB. (1991) Mapping of the acetylcholine binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: [3H]nicotine as an agonist photoaffinity label. Biochemistry 30:6987–6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. (2003) Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 63:332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirthanan S, Garcia G, 3rd, Chiara DC, Husain SS, Cohen JB. (2008) Identification of binding sites in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor for TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive positive allosteric effector. J Biol Chem 283:22051–22062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirthanan S, Ziebell MR, Chiara DC, Hong F, Cohen JB. (2005) Photolabeling the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with 4-azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzoylcholine, a partial agonist. Biochemistry 44:13447–13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JA, Ahring PK, Kastrup JS, Gajhede M, Balle T. (2014) Structural and functional studies of the modulator NS9283 reveal agonist-like mechanism of action at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 289:24911–24921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JA, Kastrup JS, Peters D, Gajhede M, Balle T, Ahring PK. (2013) Two distinct allosteric binding sites at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors revealed by NS206 and NS9283 give unique insights to binding activity-associated linkage at Cys-loop receptors. J Biol Chem 288:35997–36006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya A, Yakel JL. (2011) Allosteric modulator Desformylflustrabromine relieves the inhibition of α2β2 and α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by β-amyloid(1-42) peptide. J Mol Neurosci 45:42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D, Ratajczak E. (1984) Flash photolysis of isoxazole monitored by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Process 60:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sala F, Mulet J, Reddy KP, Bernal JA, Wikman P, Valor LM, Peters L, König GM, Criado M, Sala S. (2005) Potentiation of human alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptors by a Flustra foliacea metabolite. Neurosci Lett 373:144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H, von Jagow G. (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem 166:368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S, Henry JT, Lewis AH, Wang N, Levandoski MM. (2009) The positive allosteric modulator morantel binds at noncanonical subunit interfaces of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 29:8734–8742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel E, Steinmann ME. (2012) Structure, function, and modulation of GABA(A) receptors. J Biol Chem 287:40224–40231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Hamouda AK, Pandhare A, Duddempudi PK, Sanghvi M, Cohen JB, Blanton MP. (2009) [(3)H]Epibatidine photolabels non-equivalent amino acids in the agonist binding site of Torpedo and α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 284:24939–24947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taly A, Corringer PJ, Guedin D, Lestage P, Changeux JP. (2009) Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:733–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann DB, Sandager-Nielsen K, Dyhring T, Smith M, Jacobsen AM, Nielsen EØ, Grunnet M, Christensen JK, Peters D, Kohlhaas K, et al. (2012) Augmentation of cognitive function by NS9283, a stoichiometry-dependent positive allosteric modulator of α2- and α4-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Br J Pharmacol 167:164–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. (2005) Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol 346:967–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovozova EL. (2007) Photoaffinity labeling and its application in structural biology. Biochemistry (Mosc) 72:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Chiara DC, Xie Y, Cohen JB. (2000) Probing the structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with 4-benzoylbenzoylcholine, a novel photoaffinity competitive antagonist. J Biol Chem 275:28666–28674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltzin MM, Schulte MK. (2015) Desformylflustrabromine Modulates α4β2 Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor High- and Low-Sensitivity Isoforms at Allosteric Clefts Containing the β2 Subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 354:184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DK, Wang J, Papke RL. (2011) Positive allosteric modulators as an approach to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-targeted therapeutics: advantages and limitations. Biochem Pharmacol 82:915–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young GT, Zwart R, Walker AS, Sher E, Millar NS. (2008) Potentiation of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors via an allosteric transmembrane site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:14686–14691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart R, Vijverberg HP. (1998) Four pharmacologically distinct subtypes of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol Pharmacol 54:1124–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]