Abstract

Objectives. To assess health coverage among Mexicans with US migration experience, before and after the implementation of Mexico’s universal health care program, Seguro Popular.

Methods. I used data from the 2000 and 2010 Mexican Censuses to generate nationally representative estimates of health coverage among working-age Mexicans by migrant status.

Results. In 2000, before the implementation of Seguro Popular, 56% of Mexicans aged 15 to 60 years with no recent US migrations were uninsured compared with 80% of recently returned migrants. By 2010, the proportion uninsured declined from 56% to 35% (−38%) among nonmigrants and from 80% to 54% (−33%) among return migrants.

Conclusions. Seguro Popular has increased health coverage among Mexican return migrants, but they remain substantially underinsured. A creative and multifaceted approach likely will be needed to address Mexican immigrants’ health care needs.

Mexican migrants to the United States are a large and vulnerable population. In recent years, the mass immigration of Mexicans to the United States has been mirrored by high levels of return migration (both voluntary and forced).1 Between 2005 and 2010, nearly 1.5 million Mexicans returned home from the United States, many of them motivated by a declining US economy and increasing deportations.1 Mexican return migrants are at elevated risk for obesity, smoking, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression relative to nonmigrants, which is especially noteworthy given evidence that better health in Mexico prior to migration is associated with higher odds of emigration to the United States.2 Despite the health challenges faced by Mexican return migrants, little is known about the association between US migration and health coverage in Mexico.

In 2003, the Mexican government implemented Seguro Popular, a universal health insurance program intended to insure the tens of millions of informally employed Mexicans without access to Mexico’s employment-based social security program, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS).3 Seguro Popular has dramatically reduced uninsurance, and research suggests that Seguro Popular enrollees have higher hospital use than the uninsured.4 Yet, no studies (to my knowledge) have considered Seguro Popular’s effect on Mexican migrants. Given that Seguro Popular targeted rural, lower socioeconomic status communities, from which most Mexican migrants have historically originated,5 I examined Seguro Popular's effect on access to health care for returning migrants.

I used data from the 2000 and 2010 Mexican Censuses to identify changes in health insurance coverage during the first decade of the 21st century among recently returned working-age Mexican migrants compared with nonmigrants. This analysis makes 2 contributions to the study of migration and health. First, it provides a national-level assessment of the association between a recent migration experience and health insurance coverage among contemporary return migrants. Second, it indicates whether Seguro Popular has successfully reached return migrants. Mexican return migrants’ health coverage is relevant to US policy because undocumented Mexican immigrants frequently return to Mexico for medical treatment.6

METHODS

Data came from the 2000 and 2010 Mexican Population and Housing Censuses (PHC). The PHC is a nationally representative decennial survey administered to a 10% stratified random sample of Mexican households. At both years, PHC respondents were asked: “What state of the Republic or what country did you live in 5 years ago?”

I defined migrants as those who lived in the United States 5 years prior to the PHC (1995 and 2005, respectively). Respondents also reported their health insurance coverage, if any. Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) presents the health insurance options that were listed in the 2000 and 2010 PHCs. Because 80% of the Mexican migrants between 1995 and 2009 were working age (15–60 years), I omitted all other ages.7 The analytic sample contained 12 164 346 observations. I used survey weights to generate nationally representative estimates. Unfortunately, the PHC did not solicit information on length of migration or cause of return.

RESULTS

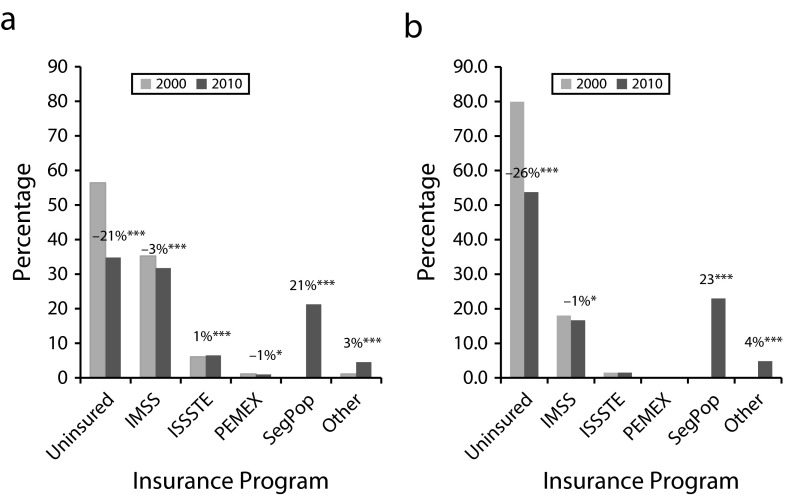

Figure 1 presents health coverage in 2000 and 2010 among nonmigrants and former US migrants in Mexico. (Table A contains a list and description of the alternative health insurance programs.) In 2000, before the implementation of Seguro Popular, more than half of Mexicans aged 15 to 60 years with no recent US migrations (56%) were uninsured. Most of the insured were covered through IMSS (35%). By contrast, fully 80% of recently returned migrants were uninsured in 2000, with almost all of the insured covered through IMSS (18%).

FIGURE 1—

Health Insurance Coverage Among Working-Age Mexicans in 2000 and 2010, by (a) Nonmigrants and (b) Return Migrants: Mexican Population and Housing Censuses 2000 and 2010

Note. These figures represent the proportions of Mexicans affiliated with each insurance program in 2000 and 2010, by migrant status (n = 12 037 836 nonmigrants and n = 126 520 return migrants). Data labels indicate the size and direction of the change in percentage affiliated with each program. Significance levels refer to the differences between 2000 and 2010 insurance coverage by program. Fewer than 1% of the respondents who reported multiple types of insurance (e.g., Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social [IMSS] and other or Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado [ISSSTE] and Seguro Popular [SegPop]) were omitted. Return migrants are those who resided in the United States 5 years before the census’s administration. Less than 0.5% of the return migrants reported affiliation with Petróleos Mexicanos [PEMEX] in either census; their participation was rounded to 0%. The proportions were weighted to yield nationally representative estimates of health coverage enrollment for the working-age (15–60 years) Mexican population in 2000 and 2010.

*P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001.

The proportion of uninsured decreased substantially by 2010 because nonmigrants and those recently returned from the United States enrolled in Seguro Popular (21% and 26%, respectively). Enrollment in preexisting programs remained relatively stable among return migrants and nonmigrants, suggesting, as expected, that Seguro Popular largely accounted for the reduction in uninsurance among working-age Mexicans.

Although the absolute decline in the percentage uninsured was slightly greater among recently returned migrants relative to nonmigrants, the proportional odds of transitioning from uninsured to insured were greater among nonmigrants. In other words, the greater percentage decline in uninsurance among return migrants was driven to some extent by the greater proportion of at-risk (uninsured) returnees in 2000. Among nonmigrants, the proportion uninsured decreased from 56% to 35% between 2000 and 2010—a 38% reduction in the rate of uninsurance. By contrast, the proportion uninsured among recently returned migrants decreased from 80% to 54%—only a 33% decline. Analyses (not shown) found that the negative association between migration and health coverage was stronger among women than among men and that following adjustment for potential demographic and socioeconomic confounders, the negative association between US migration and the odds of being insured remained robust.

DISCUSSION

Perhaps as a result of their absence during major enrollment periods, limited social networks, and persistent overrepresentation in the informal occupations, working-age Mexicans who recently returned from the United States remain substantially underinsured relative to nonmigrants. Despite the 26% reduction in uninsurance among returnees, the relative decline has been slower than among nonmigrants. Future research might explore targeted programs specifically intended to protect international migrants. The Philippines, for example, provides premigration training and insurance to workers living abroad through their Overseas Workers Welfare Administration. Of course, any binational program would face the challenge of incorporating millions of undocumented migrants who, for obvious reasons, often prefer to remain “off the books.”

This study has implications for US policy and the well-being of Mexicans in the United States. The underinsurance identified among recently returned migrants and the fact that the Affordable Care Act does not address access to care among undocumented Mexican immigrants indicate a need for policies that directly address the health care needs of current and former undocumented Mexican migrants. Given the US Congress’s inability to pass comprehensive immigration reform or approve a binational health care agreement between the United States and Mexico, which was drafted in 2004, and the current climate of hostility toward Mexican immigrants, a creative and multifaceted approach will likely be needed to address Mexican immigrants’ health care needs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the Carolina Population Center for training support (T32 HD007168) and for general support (R24 HD050924) of this research.

Data for this project were made available via the Minnesota Population Center, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.3 [machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. The data were originally collected by the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Informatics, Mexico.

I would also like to thank Jacqueline Hagan, Robert Hummer, and Krista Perreira for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Passell J, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A. Net Migration From Mexico Falls to Zero–and Perhaps Less. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullmann SH, Goldman N, Massey DS. Healthier before they migrate, less healthy when they return? The health of returned migrants in Mexico. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(3):421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knaul FM, Frenk J. Health insurance in Mexico: achieving universal coverage through structural reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(6):1467–1476. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380(9849):1259–1279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fussell E. Sources of Mexico’s migration stream: rural, urban, and border migrants to the United States. Soc Forces. 2004;82(3):937–967. [Google Scholar]

- 6.González-Block MA, Sierra-de la Vega LA. Hospital utilization by Mexican migrants returning to Mexico due to health needs. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:241–248. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica 2009: Panorama Sociodemografíco de México Principales Resultados. Aguascalientes City, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; 2011. [Google Scholar]