Abstract

Urgent intervention is required to improve the 5 year survival rate of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). While the four-drug regimen, FOLFIRINOX (comprising irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and leucovorin), has a better survival outcome than the more frequently used gemcitabine, the former treatment platform is highly toxic and restricted for use in patients with good performance status. Since irinotecan contributes significantly to FOLFIRINOX toxicity (bone marrow and gastrointestinal tract), our aim was to reduce the toxicity of this drug by a custom-designed mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSNP) platform, which uses a proton gradient for high-dose irinotecan loading across a coated lipid bilayer (LB). The improved stability of the LB-coated MSNP (LB-MSNP) carrier allowed less drug leakage systemically with increased drug concentrations at the tumor sites of an orthotopic Kras-derived PDAC model compared to liposomes. The LB-MSNP nanocarrier was also more efficient for treating tumor metastases. Equally important, the reduced leakage and slower rate of drug release by the LB-MSNP carrier dramatically reduced the rate of bone marrow, gastrointestinal and liver toxicity compared to the liposomal carrier. We propose that the combination of high efficacy and reduced toxicity by the LB-MSNP carrier could facilitate the use of irinotecan as a first-line therapeutic to improve PDAC survival.

Keywords: irinotecan, FOLFIRINOX, proton gradient, lipid bilayer, mesoporous silica nanoparticle, pancreatic cancer, toxicity reduction

Graphical Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a fatal disease with a 5 year survival rate of less than 6%.1 Currently, the major chemotherapy modalities include either a single reagent, gemcitabine (GEM), or a four-drug regimen, FOLFIRINOX, which includes irinotecan (IRIN), oxaliplatin (OX), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and leucovorin (LV). While FOLFIRINOX has a better response rate than GEM (31.6% versus 9.4%), with improved survival (11 months versus 6.8 months), the former combination is significantly more toxic and restricted to a minority of PDAC patients with good performance status.2 Irinotecan contributes significantly to this toxicity, including a severe impact on the bone marrow (e.g., neutropenia), liver (e.g., necrosis and steatosis), and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea).2–4 Thus, there is a great need for a treatment regimen that reduces irinotecan toxicity, with a view to improving the available drugs for first-line therapy in PDAC.

One approach to reducing irinotecan toxicity, with maintenance of efficacy, is high drug encapsulation in a nanocarrier with protected delivery to the cancer site while reducing systemic leakage. Different carrier types, including polymeric particles and liposomes, have been employed with some success for irinotecan delivery.5–12 However, while polymeric nanoparticles showed promising in vitro results, the limited capacity to load irinotecan (<1% w/w), accompanied by premature drug release (e.g., 40% in 5 h), failed to achieve significant toxicity reduction in vivo.9 While liposomes could achieve high irinotecan loading capacity through the use of ammonium sulfate or protonating agents,5, 7, 8, 10, 11 carrier instability under shear and osmotic stress conditions, as well as bilayer disruption by serum proteins, have been shown to result in premature drug release and toxicity.13–15 While a new liposomal carrier for irinotecan (MM-398), developed by Merrimack, showed an improved survival rate of PDAC patients in a phase 3 clinical trial, the relatively high rate of GI tract and bone marrow toxicity has resulted in a black box warning for severe and life-threatening diarrhea and neutropenia.16, 17 Human subjects participating in MM-398 clinical trials also showed significant elevations of liver enzymes, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT).18 Nonetheless, MM-398 received FDA approval for use in PDAC for patients failing to respond to GEM therapy and is marketed as Onivyde.17

Because of the concern that liposomal carriers may fail to improve the safety of highly toxic drugs such as irinotecan, we were interested in using a supported lipid bilayer (LB) that is applied to mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) to see if this will result in a more stable carrier. Due to the large internal surface area that can be used for drug packaging, tunable pore sizes, carrier stability and controlled drug release abilities, MSNPs have been demonstrated to constitute a versatile and multifunctional nanocarrier platform for cancer therapy.19–32 Moreover, MSNPs are biodegradable and proven to be safe in extensive animal testing.23, 27–30, 32, 33 While it is possible to introduce irinotecan or camptothecin into MSNPs by soaking, this method is relatively inefficient (loading capacity <10 wt%)19, 34 and may result in poor drug retention.21 However, we have recently developed a biofilm technique that can be used for rapid GEM encapsulation by a supported LB.32 While a number of LB coating procedures have been published, including liposomal interaction and fusion with the particle surface35, 36 or solvent exchange utilizing EtOH-dispersed lipid solutions,37 the use of a biofilm technique provides more complete coating, rapid encapsulation, and improved carrier stability.32 Not only has this allowed LB-MSNPs to achieve a loading capacity of up to 40 wt% GEM, but it has also enabled co-delivery of paclitaxel (PTX), which could be incorporated in the LB.32 This allowed us to develop a synergistic and ratiometric-designed carrier for PDAC treatment in an orthotopic human PDAC model in mice.32 Recently, Zhang et al. reported a polymer-lipid supported MSNP for delivery of irinotecan, but the drug loading was lower (i.e., ~16 wt%).38

In this paper, we introduce a novel design feature for the LB-MSNP platform in which the LB is used to encapsulate a protonating agent; this allows remote loading of a high irinotecan drug load that utilizes the drug’s weak basic properties (pKa = 8.1). Moreover, the increased ability of the supported LB also allowed us to perform comparative analysis to a liposomal equivalent, where a nonsupported LB vesicle was used for remote loading of irinotecan by a trapping agent, triethylammonium sucrose octasulfate (TEA8SOS).8, 16 Not only did the MSNP carrier achieve higher loading capacity and tumor killing than the liposomal formulation in a robust orthotopic PDAC model, but it also prevented irinotecan toxicity due to improved carrier stability and reduced leakage. This provides an innovative approach for reducing the toxicity of highly toxic chemotherapeutic agents by a LB-coated carrier, which could allow the use of irinotecan as a first-line treatment option for PDAC rather than being reserved for GEM treatment failure (current FDA-improved indication for the use of the liposomal carrier).

RESULTS

High irinotecan loading in MSNP through the use of a coated LB and a proton gradient

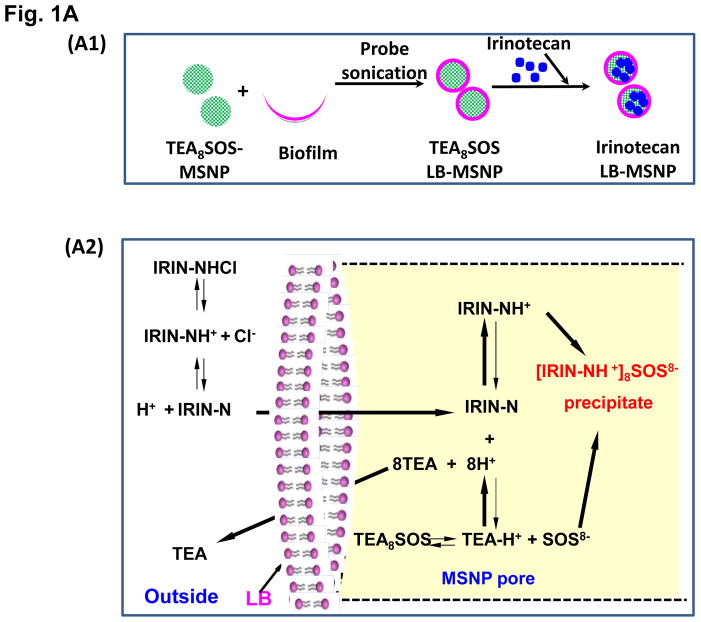

Our first attempt was to produce a MSNP carrier that encapsulates irinotecan by a LB coat that provides rapid and uniform pore sealing.32 This allowed passive entrapment of 22 wt% irinotecan (relative to MSNP weight). In order to further improve the loading capacity, we also determined whether entrapment of a protonating agent that converts amphipathic irinotecan, capable of diffusing across the LB, into a hydrophilic derivative that is retained in the pores (Figure 1 A1). We and others have used this entrapment procedure in liposomes for effective import and encapsulation of weak basic drugs, such as GEM and irinotecan.5, 30, 39 While it has never been used in a MSNP platform previously, the polyanionic compound, TEA8SOS, was used in MM-398 to entrap irinotecan.8 TEA8SOS is a proton generating agent that releases eight H+ ions and octavalent SOS8− upon hydrolysis (Figure 1 A2). Ion-exchange chromatography was used to generate TEA8SOS, which was soaked into MSNP, as described in Methodssection.8 The soaked particles were introduced to a round bottom flask coated with a lipid biofilm, comprised of DSPC/cholesterol/DSPE-PEG2000 at a molar ratio of 3:2:0.15. Sonication of the suspension yielded LB-coated particles, which contain the entrapment agent (Figure 1 A1). These particles were immediately incubated in an irinotecan solution, allowing the drug to be imported, protonated and entrapped in the pores as a gel-like precipitate in association with SOS8− (Figure 1 A1, A2, B). This allowed us to achieve an irinotecan loading capacity up to 80 wt% (Figure 1B), which approximates the theoretical maximum loading capacity (~110 wt%) of the porous carrier with a combined surface area of 850 m2/g and a pore volume of ~0.7 cm3/g, as previously demonstrated.32 Subsequent studies were performed with particles containing 50 wt% irinotecan.

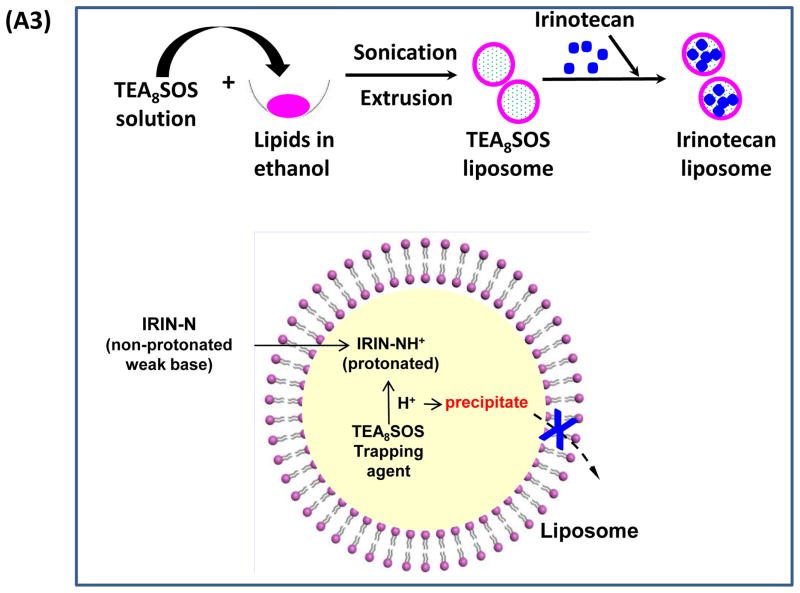

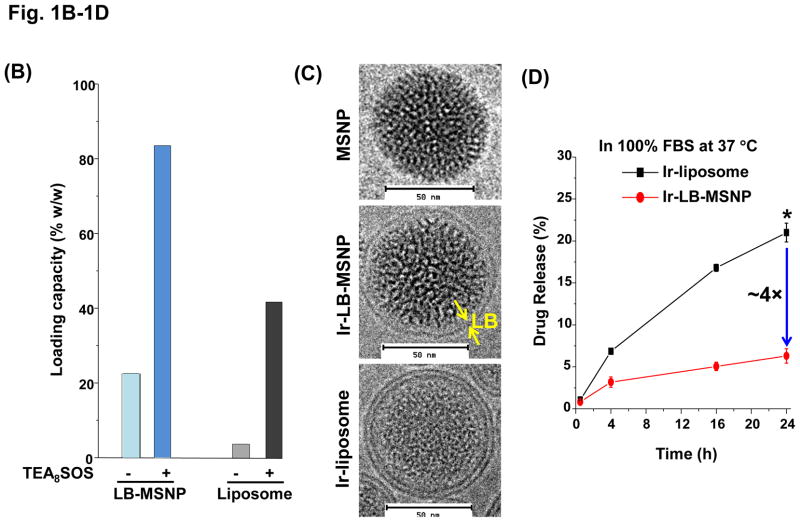

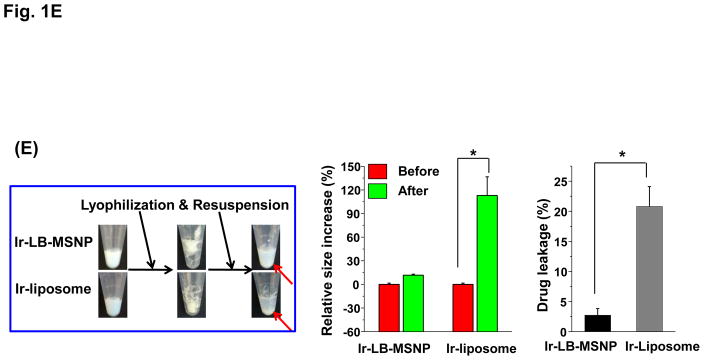

Figure 1. Establishing LB-MSNP and liposomal irinotecan carriers that use a protonating agent for drug loading.

(A) Schematics depicting the synthesis method and loading of irinotecan by LB-MSNPs and liposomes. (A1) After soaking TEA8SOS into the MSNP particles, the pores are sealed by a LB, derived from sonication of a lipid biofilm.32(A2) TEA8SOS-soaked particles are incubated in an irinotecan solution, allowing the amphipathic drug to diffuse across the lipid bilayer for protonation by TEA8SOS (TEA8SOS↔ 8TEA + 8H+ + SOS8−). The lipid-soluble TEA exits the particle, while the H+ converts irinotecan to a hydrophilic derivative that cannot cross the LB. The protonated drug interacts with SOS8− to form gel-like precipitate, which is retained in the pores. (A3) Same technique was used to produce a liposomal equivalent for irinotecan entrapment.8 (B) Assessment of the drug loading capacity (DLC) of the Ir-LB-MSNP and Ir-liposome carriers. DLC= [the total amount of irinotecan (m0) – non-encapsulated irinotecan (m1)]/[the total amount of particle (mMSNP or mlipid)]×100%. The inclusion of TEA8SOS had a negligible effect on the hydrodynamic size and ζ-potential of the particles. Hydrodynamic size and ζ-potential data are shown in Table S1. (C) CryoEM images of the empty, noncoated MSNP, Ir-LB-MSNP and Ir-liposome carriers. The technique is sensitive enough to visualize irinotecan precipitation in the liposome. (D) Carrier stability was assessed by incubation in 100% serum at 37 °C for 24 h and drug leakage was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. (E) Carrier stability, as determined by the change in hydrodynamic diameter and % drug leakage, following lyophilization and water resuspension.

In order to compare the efficacy and safety of the irinotecan-loaded LB-MSNPs (Ir-LB-MSNP) with a liposomal carrier using TEA8SOS, liposomes were constructed by a procedure analogous to that of MM-398 (Figure 1A3).8 This yielded a liposome (designated “Ir-liposome”) with ~40 wt% irinotecan loading capacity; that is considerably higher than producing a liposome without the entrapment agent (~5 wt%) (Figure 1B). Cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) revealed particle sizes of ~75 and ~80 nm for liposomes and LB-MSNPs, respectively (Figure 1C). High-magnification cryoEM images confirmed that there was uniform coating of Ir-LB-MSNPs by an intact ~7 nm thick bilayer. Low-magnification cyroEM images showed that the LB was intact in >99% of the particles (Figure S1). This confirms the reproducibility of the one-step encapsulation protocol, which holds significant advances over other methods of MSNP bilayer coating.32

Since our major hypothesis is that LB-MSNP could improve the carrier stability compared to liposomes, both carriers were incubated in serum and lyophilized to determine their drug retention ability and irinotecan leakage. Both carriers were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 100% serum, with continuous and gentle shaking. Since adsorption of serum proteins interferes with cryoEM visualization, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was used, instead, to determine drug release in the carrier suspensions; this showed <6% premature irinotecan release by LB-MSNPs, compared to ~22% from liposomes (Figure 1D). However, particle storage in a serum-free suspension for 90 days at 4 °C showed that both carriers had high colloidal stability, with minor (<5%) premature drug release or change in hydrodynamic particle size (<5%). Conversely, particle lyophilization in a cryo-protective 5% dextrose solution40 showed significant differences in carrier stability upon resuspension in water (Figure 1E). Thus, while Ir-LB-MSNPs did not change the hydrodynamic size and only led to 2.7% drug release, liposomes were visibly aggregated and released 20.8% of their irinotecan content. This confirms that although the LB coated carriers look morphologically similar, LB-MSNPs are significantly more stable than liposomes.

Improved biodistribution, pharmacokinetics (PK) and irinotecan delivery by LB-MSNP compared to liposomes in a Kras-derived orthotopic PDAC model

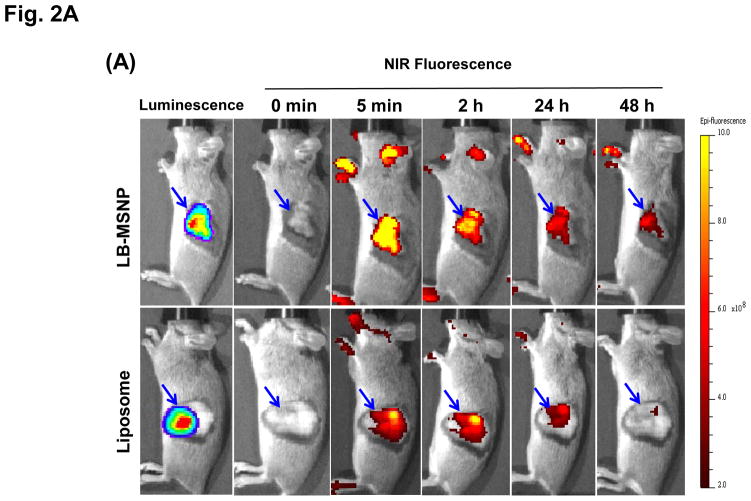

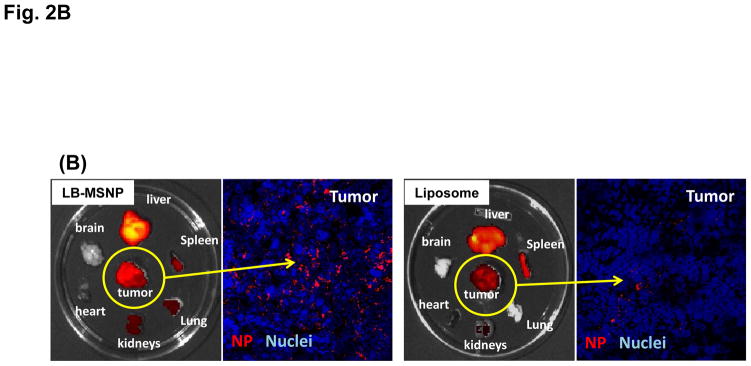

Biodistribution and PK studies were performed in immunocompetent B6/129 mice, orthotopically implanted with a luciferase-expressing cell line derived from a spontaneous PDAC tumor in a transgenic KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53LSL-R172H/+; Pdx-1-Cre (KPC) animal.41 The KPC-derived orthotopic model mimics human PDAC in the Kras mutation, expression of a relatively abundant stroma, local tissue invasion, and development of metastases.42–44 Primary tumors developed at the orthotopic implant site within 2–3 weeks, with appearance of metastases at ~5 weeks, agreeing with the literature (Figure S2).42, 44 In order to follow the biodistribution of the irinotecan carriers to the tumor site, animals were IV injected with near-infrared (NIR) labeled (Dylight 680) liposomes or LB-MSNPs, 3 weeks after orthotopic implantation (Figure 2A). IVIS imaging was obtained prior to (column 2) and following IV injection of 100 mg/kg labeled LB-MSNPs or liposomes at the indicated time points (columns 3–6, Figure 2A). This was coupled with bioluminescence IVIS imaging to detect luciferase expression in the developing tumors in animals receiving intraperitoneal (IP) injection of D-Luciferin (Figure 2A, the first column). Robust fluorescence intensity was observed at the tumor sites within 2 h of LB-MSNP injection, following which the signal was sustained for at least 48 h. In contrast, the NIR signal intensity was dimmer and disappeared more rapidly in mice injected with liposomes (with similar labeling efficiency). This was also confirmed by ex vivo imaging of the tumors and major organs collected from the animals, following sacrifice after 24 h postinjection (Figure 2B). Ex vivo imaging was also carried out after 48 h, which confirmed stronger NIR signal intensity in the operator-defined region of interest (ROI) in LB-MSNP compared to liposome-treated animals (Figure S3). In addition to abundant particle uptake at the tumor site, the liver and spleen were also major sites of particle distribution. Little signaling was obtained in the lung, heart and kidney. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) to quantify the silicon (Si) abundance in the tumor tissues and major organs, demonstrated that ~3% of the total administered elemental Si dose could distribute to the developing tumor sites (Figure S4). This represents exceptionally good biodistribution compared to liposomes, polymeric micelles, gelatin and MoS2/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, where the percentage of particles distributing to the PDAC site amounted to 0.2–2.4%.45–49 We also obtained tumor sections for visualization of the intratumoral distribution of NIR-labeled particles by confocal microscopy; this demonstrated higher particle abundance at the tumor site after 24 hrs for LB-MSNPs compared to liposomes (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Biodistribution of the Ir-LB-MSNPs and Ir-liposomes.

(A) Interval IVIS imaging over 48 h to compare the biodistribution of IV injected NIR-labeled carriers to the KPC-derived orthotopic tumor site (n=3). NIR fluorescence images in representative animals after IV injection of 100 mg/kg NIR-labeled LB-MSNPs or liposomes are shown. (B) Ex vivo imaging of explanted organs in the same experiment; animals were sacrificed after 24 h. Confocal microscopy confirmed a higher abundance of NIR-labeled LB-MSNP compared to liposomes at the tumor site. (C) Irinotecan tumor content was determined in an orthotopic KPC-derived xenograft model (n=3). Animals received IV injection of an irinotecan dose equivalent to 60 mg/kg for the different drug formulations. Following animal sacrifice after 24 h, tumor tissues were collected for the measurement of irinotecan content by HPLC. Irinotecan content was expressed as % total injected dose per gram of tumor tissue (%ID/g). Data represent mean ± SD, *p<0.05. (D) HPLC measurement of plasma irinotecan concentration in the same experiment. Data represent mean ± SD, * p<0.05.

In order to assess irinotecan content at the tumor site, the equivalent of 60 mg/kg drug was injected as a single dose in the form of free drug, Ir-LB-MSNP (60 mg/kg drug; 120 mg/kg particle dose) or Ir-liposomes (60 mg/kg drug; 150 mg/kg particle dose). Animals were sacrificed after 0.5, 4, 24, and 48 h for blood collection and tumor harvesting. These tissues were used for HPLC analysis to quantify the irinotecan tissue content, which was 5- and 2-fold higher for Ir-LB-MSNPs and Ir-liposomes than for free drug at 24 h (Figure 2C). Circulatory half-life for irinotecan was calculated by using HPLC quantification of the plasma drug concentration, and to 11, 8.7 and 1.0 h for LB-MSNPs, liposomes, and free drug, respectively (Figure 2D). Logistical constraint of the volume of blood obtainable from mice, precluded us from determining the blood residence time of the carriers. We also performed a biodistribution and PK study in a subcutaneous PANC-1 xenograft model, in which we observed 30- and 4-fold increases in tumor drug content for Ir-LB-MSNPs and Ir-liposomes, respectively, over free drug (Figure S5). We also compared the drug content of individual organs (Figure S6). This demonstrated a 0.8-, 0.2- and 0.2-fold higher drug content in liver, spleen, and intestinal tissues, respectively, for the Ir-liposomes compared to the Ir-LB-MSNP at 24 h post-injection. No significant difference was seen for the kidney.

Ir-LB-MSNP provides more efficacious killing than free drug or Ir-liposomes in an orthotopic PDAC model

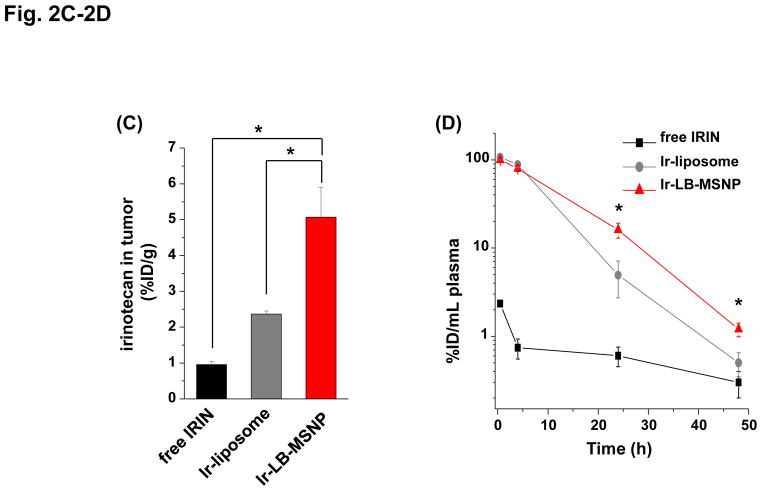

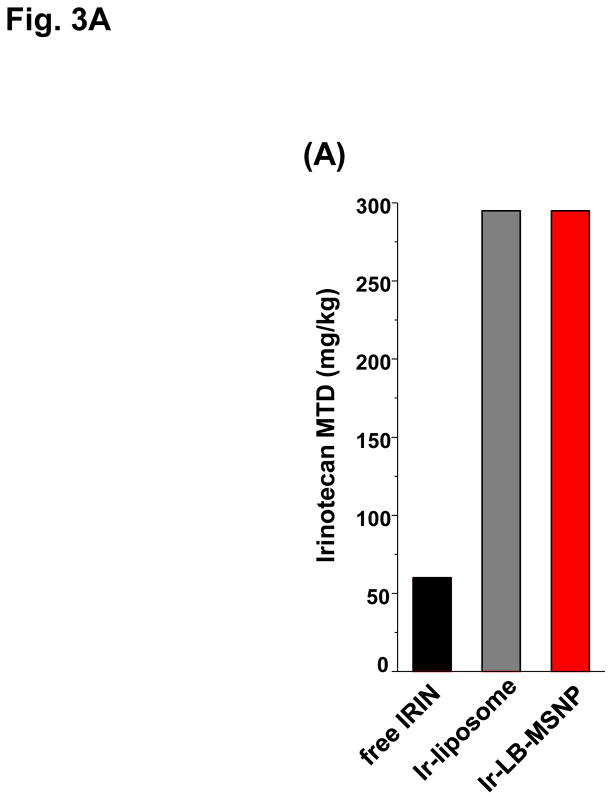

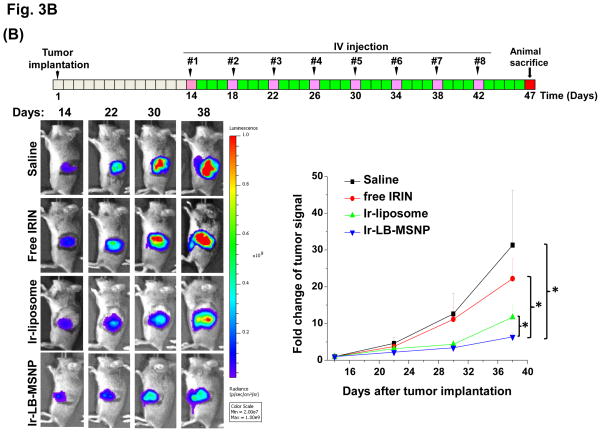

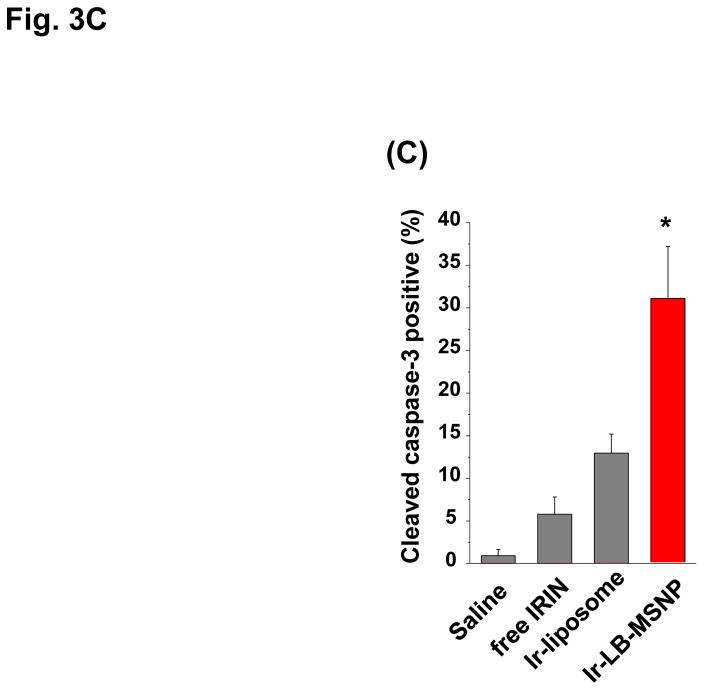

In order to develop a dose-seeking schedule for efficacy assessment, we used a protocol from the U.S. National Cancer Institute to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in healthy mice.8 This assessment demonstrated a MTD of 60, 295, and 295 mg/kg for free irinotecan, Ir-liposomes, and Ir-LB-MSNPs, respectively (Fig. 3A). A drug dose of 40 mg/kg (equivalent to 66.7 or 13.3% of the MTD for free drug or encapsulated drug quantities) was chosen for subsequent experiments. These doses are equivalent to nanoparticle doses of 80 or 100 mg/kg for Ir-LB-MSNPs or Ir-liposomes, respectively. IV injection commenced on day 14 after orthotopic tumor implantation of 2×106 KPC cells; at this time, the mean primary tumor size was ~5 mm, without macro-metastases. IV injection was repeated every 4 days, for up to 8 repeat repetitions (Figure 3B). The control group included animals receiving IV saline only. Orthotopic tumor growth was monitored at set time points by IVIS bioluminescence imaging (Figure 3B). Quantitative expression of tumor growth by IVIS software to determine imaging intensity in the ROI, demonstrated significantly slower tumor growth by Ir-LB-MSNPs treatment compared to saline, free drug or Ir-liposomes (Figure 3B). Effective antitumor efficacy was also measured according to the rates of apoptosis in tumor explants, collected from animals sacrificed on day 40–47. Utilizing an immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining protocol for the detection of activated (cleaved) caspase-3, we observed ~25% apoptotic cell death in Ir-LB-MSNP-treated mice, compared to ~6% and ~11% for free irinotecan or Ir-liposomes, respectively (Figure 3C). Representative IHC images are shown in Figure S7. Although we did not set out to perform an official survival study, it was possible to use a Kaplan-Meier data display after 47 days to compare the number of surviving animals at different stages of the investigation (Figure S8). This demonstrated improved survival of both carriers over free drug, including better survival rate of Ir-LB-MSNP over the liposomal preparation (Figure S8).

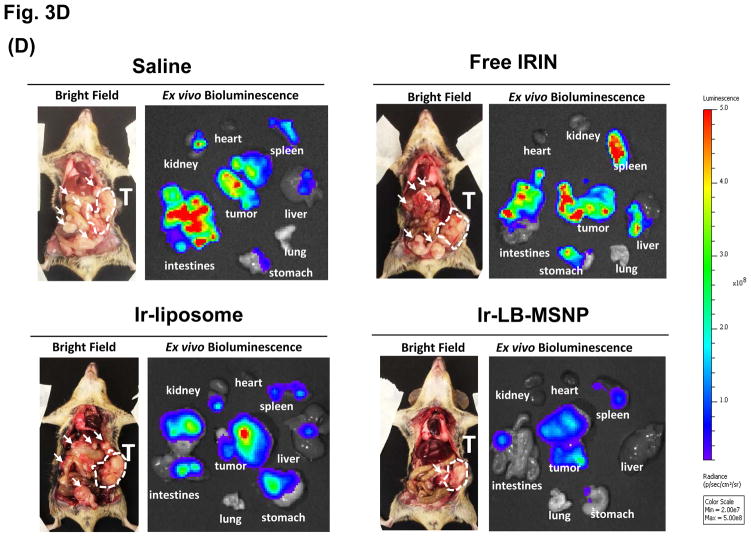

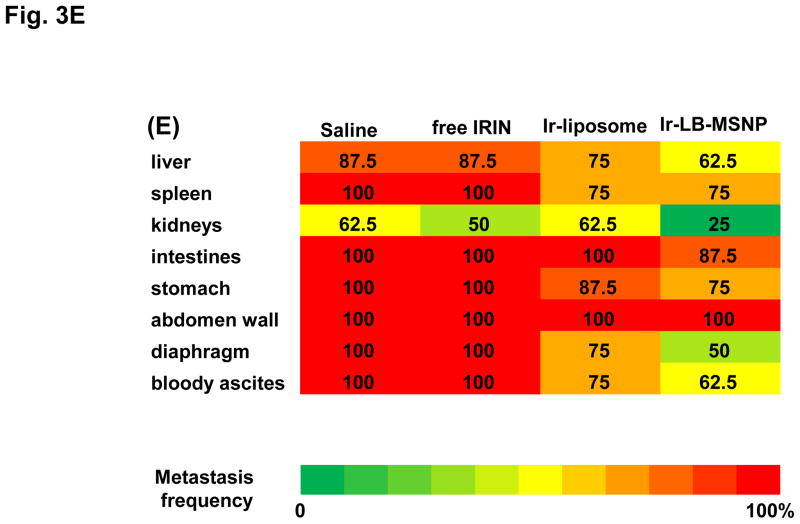

Figure 3. Differential tumor inhibitory effect of the free drug and encapsulated irinotecan carriers in the KPC-derived orthotopic tumor model.

(A)Assessment of the MTD in an acute dose finding study, using a NCI protocol. (B) Growth inhibition of KPC-derived orthotopic tumors in B6/129 mice, following IV administration of 40 mg/kg free drug or encapsulated irinotecan every 4 days for up to 8 administrations. Interval IVIS imaging was used for monitoring tumor growth, which was quantitatively expressed according to the image intensity at the operator-defined ROI. (C) Quantitative analysis of apoptosis (using IHC staining for cleaved caspase-3)at the primary tumor site of the animals after treatment (sacrificed on days 40–47). (D) Representative autopsy results and ex vivo imaging of bioluminescence intensity in the moribund animals (sacrificed on days 40–47) to show treatment impact on surrounding metastases. Visible metastatic spread could be seen in the stomach, intestines, liver, spleen, kidneys, diaphragm, and abdominal wall. There was no infiltration of the heart or lung. (E) Heat map display to summarize the comparative analysis of tumor spread determined by quantitative ex vivo imaging in (D). Data represent mean ± SEM,* p<0.05.

Animal autopsy was performed to assess local tumor spread and appearance of metastases (Figure 3D). In addition to direct tumor invasion of the stomach, intestines, liver, spleen, kidneys, diaphragm, and abdominal wall, numerous macroscopic metastatic foci could be seen in saline-treated animals, which also developed hemorrhagic ascites. While free irinotecan failed to affect metastasis, Ir-liposomes provided a moderate reduction of bioluminescence intensity at the metastatic sites (Figure 3D). In striking contrast, Ir-LB-MSNP treatment exerted a potent inhibitory effect, with evidence of dim bioluminescence outside the primary tumor region during IVIS imaging (Figure 3D). This was especially prominent in the region of the kidney, which showed a higher but nonsignificant content of irinotecan during HPLC analysis (Figure S6). The heat map in Figure 3E provides a quantitative display of treatment impact on tumor metastasis.

LB-MSNPs but not liposomes improve the safety of irinotecan delivery in the mouse orthotopic model

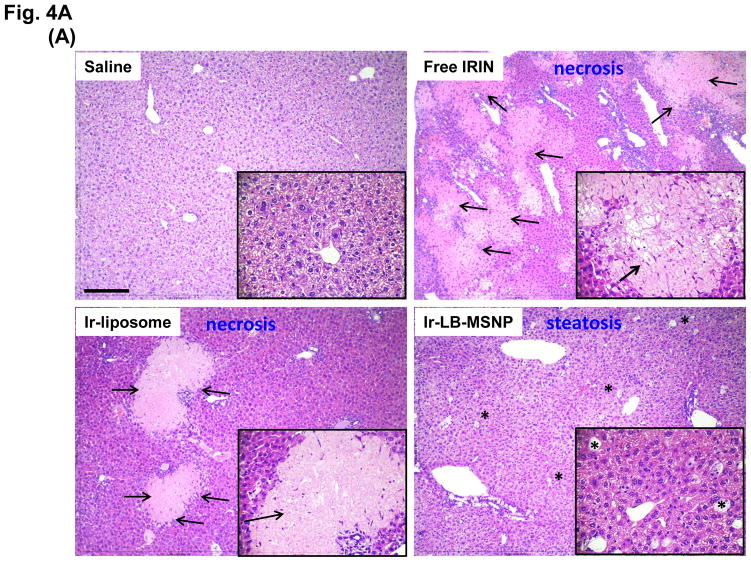

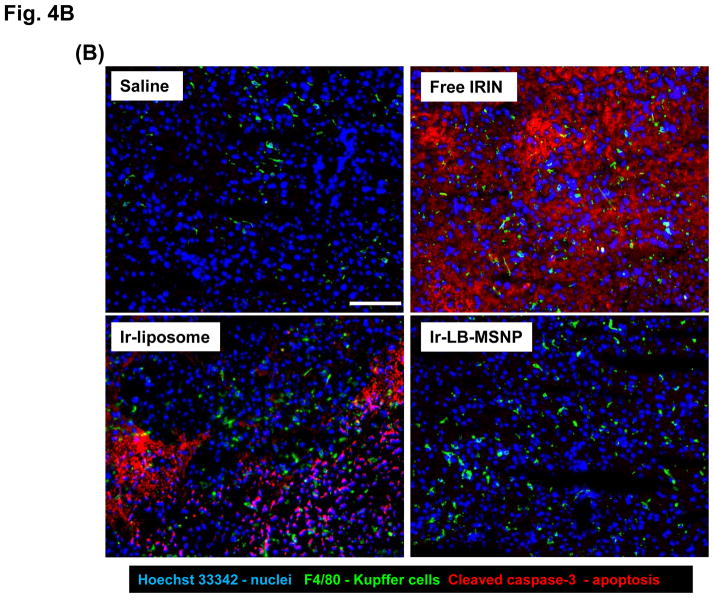

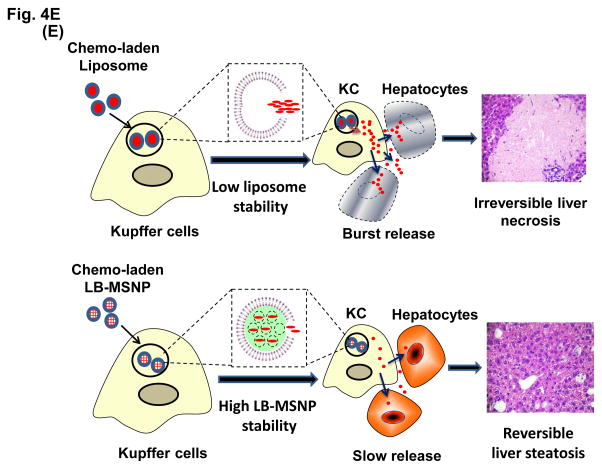

Since irinotecan contributes in a major way to FOLFIRINOX toxicity, the possibility of reducing drug toxicity by encapsulated delivery is a major study objective. MTD assessment showed that both carriers are capable of increasing the acute lethal dose ~5-fold over free drug (Figure 3A). In order to address irinotecan toxicity through encapsulated drug delivery (Figure 3B), liver, sternal bone marrow, and intestinal tissues were collected from the sacrificed animals in the efficacy study. These are the major target organs for irinotecan toxicity in PDAC patients.2–4 Histological examination of the liver demonstrated severe and extensive hepatocyte necrosis in animals treated with the free drug (Figure 4A). This is reflected by the presence of pyknotic and fragmented nuclei in hepatic cells.50 While the severity of liver damage was somewhat reduced by Ir-liposomes, extensive hepatic necrosis was observed (Figure 4A). In contrast, Ir-LB-MSNP treated animals only exhibited minor steatosis, a reversible drug-induced stress response, without necrosis (Figure 4A).51, 52 The histological data were also confirmed by IHC analysis, in which liver tissue was used to stain Kuppfer cells (KC) (with a FITC-labeled anti-F4/80 antibody), apoptotic cells detected with a RITC-labeled antibody (recognizing cleaved caspase-3) and cellular nuclei with Hoechst 33342 (a blue dye) (Figure 4B). Examination of the stained sections under a fluorescence microscope demonstrated extensive apoptosis throughout the liver of animals treated with the free drug. Animals receiving treatment with Ir-liposomes demonstrated less apoptosis, which frequently involved KC or adjacent hepatic tissue. In contrast, no apoptosis was seen in the livers of animals treated with Ir-LB-MSNP.

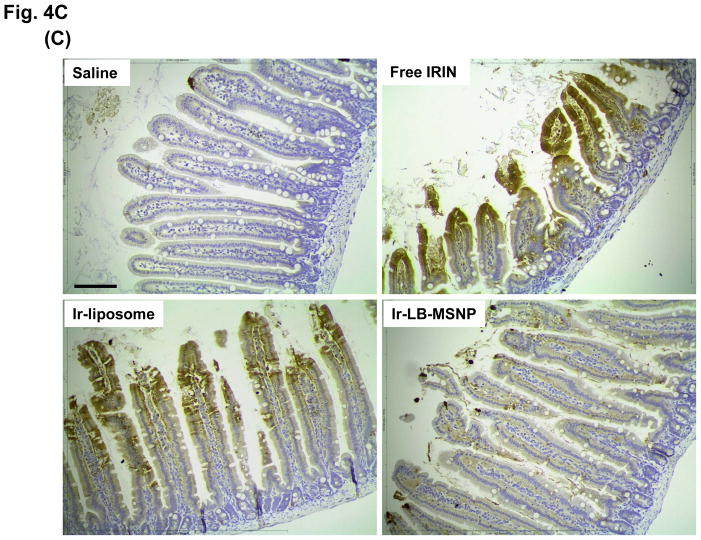

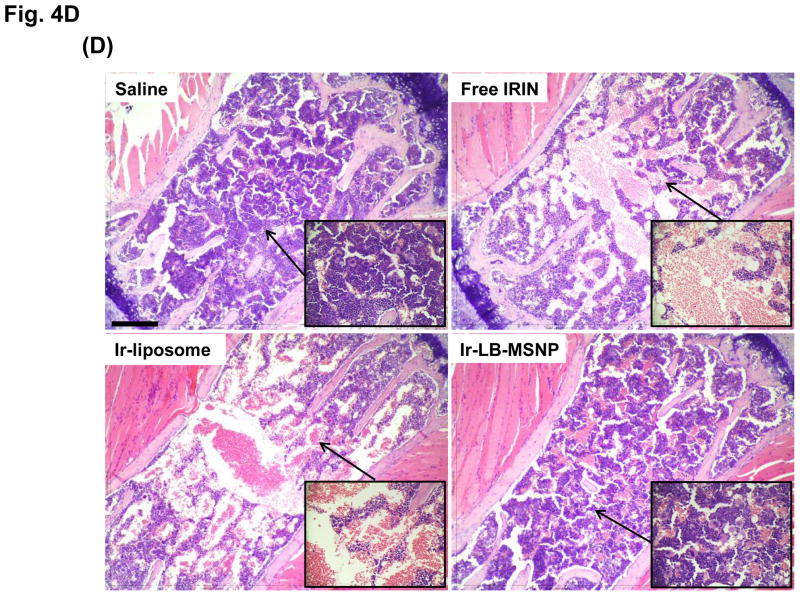

Figure 4. Comparative analysis of toxicity reduction by Ir-LB-MSNPs vs. Ir-liposomes.

(A) Liver histology obtained from representative moribund animals (sacrificed on days 40–47) using tissue from the experiment shown in Figure 3B. The arrows in the H&E stained sections point to necrotic liver tissue, while sites marked with an asterisk denote steatosis. Bar is 200 μm. (B) Dual IHC staining of cleaved caspase-3 (apoptosis marker, red) and F4/80 (KC marker, green) in the livers of animals receiving different irinotecan formulations at a dose equivalent of 60 mg/kg, followed by sacrifice at 24 h. The nucleus was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bar = 100 μm. (C) IHC staining for cleaved caspase-3, with H&E counterstaining to reveal the spread of apoptosis and blunting of the intestinal villi in the same treated animal groups studied in Figure 3B. The bar represents 100 μm. (D) Separate experiment, in which a 40 mg/kg dose-equivalent of irinotecan, IV injected every second day, three times, was used to study the impact on sternal bone marrow. The sternums were collected on day 7 for embedding, decalcification and H&E staining. The bar represents 200 μm. (E) Schematic to explain the differential hepatotoxicity of Ir-LB-MSNP and Ir-liposome formulations in the liver. We propose that the injected nanocarriers are initially taken up by KCs, where carrier disintegration leads to the irinotecan release to bystander hepatocytes. The subsequent rate of carrier disintegration and drug release to the hepatocytes could determine whether the extent to which the irinotecan is metabolized and rendered inactive. We further hypothesize that the higher instability of the liposomal carrier leads to more rapid drug release than the more stable Ir-LB-MSNP, which explains the differences in apoptosis and necrosis.

While H&E staining of the GI tract did not reveal microscopic evidence of toxicity in any of the treatment groups, IHC staining for cleaved caspase-3 demonstrated the presence of apoptotic cells and blunting of the intestinal villi by the free drug (Figure 4C). While treatment with Ir-liposomes protected against blunting of the villi, IHC staining revealed the presence of apoptosis in apical enterocytes. This is in clear contrast to treatment with Ir-LB-MSNPs, which did not result in any apoptosis or damage to the villi (Figure 4C).

Bone marrow toxicity was studied in a separate experiment, in which animals received three injections of a 40 mg/kg irinotecan dose equivalent, as described above. After sacrifice, sternal bone marrow was collected to evaluate myelotoxicity by H&E staining (Figure 4D).53 While animals treated with free drug or Ir-liposomes showed extensive marrow damage, evidenced by filling of <30% of the marrow space by hematopoietic cells fill,54 there was no change in marrow cellularity in Ir-LB-MSNP-treated animals (Figure 4D). Moreover, damage to the bone marrow by the free drug or Ir-liposomes was accompanied by peripheral blood neutropenia, while Ir-LB-MSNP treatment showed a nonsignificant decline in neutrophil count (Figure S9). All considered, these data demonstrate a significant reduction in systemic and target organ toxicity during treatment with Ir-LB-MSNP, while the liposomal carrier still exhibits substantial organ toxicity.

DISCUSSION

We developed a custom-designed mesoporous silica nanoparticle platform, using a supported LB and a proton-generating entrapping agent, for high dose irinotecan loading and delivery and tested it in a KPC-derived pancreatic cancer model in immunocompetent mice. The improved stability and loading capacity of the carrier improved the biodistribution, circulatory half-life, and drug tumor content of irinotecan compared to an in-house synthesized MM-398 liposome equivalent, using the same loading procedure and trapping agent (TEA8SOS). Not only was Ir-LB-MSNP more effective at inducing tumor killing at the primary tumor site, but it was also more active for treating metastases. Equally important, the LB-MSNP carrier did not induce pronounced systemic toxicity, which is in stark contrast to liposomes that had an adverse impact on the bone marrow, GI tract, and the liver. We ascribe the toxicity reduction with maintenance of treatment efficacy to the increased carrier ability of LB-MSNPs compared to that of liposomes. Thus, the LB-MSNP carrier provides an innovative approach for the introduction of irinotecan to the treatment of PDAC, with the possibility to promote the use of this drug, as a first-line consideration rather than being reserved for patients with failure of GEM treatment, as is currently the case for the recent FDA-improved liposomal carrier.

We have developed a robust MSNP carrier for irinotecan, with morphological resemblance to a liposomal equivalent. However, in addition to the superior drug encapsulation provided by an intact supported LB, the LB-MSNPs also allow dense drug packaging against the porous silica sidewalls as a result of bonding and/or electrostatic interactions.29, 55, 56 This allowed us to achieve improved irinotecan loading capacity, which provides superior killing efficiency at the orthotopic tumor site, compared to liposomes. The improved loading capacity is further assisted by the supported LB stability, which improves cargo protection compared to the liposomal bilayer during blood circulation and biodistribution to the tumor site. We propose that the decreased fluctuation of the supported LB, presumably as a result of the robust electrostatic and van der Waals interactions with the particle surface, reduces the lipid loss due to serum protein interactions with a nonsupported lipid bilayer (liposome). A supported LB may also protect the carrier against complement-mediated lysis and the shear forces generated during blood flow.13, 14, 35, 36, 56–60 For instance, doxorubicin-loaded DOPC liposomes exhibit ~40% drug leakage within 24 h in a simulated serum-containing biofluid environment at 37°C.56 This is in accordance with our finding that, while effective as a nanocarrier, Ir-liposomes are significantly less stable than Ir-LB-MSNPs in whole serum or following particle lyophilization and resuspension (Figure 1 D, E). Premature release of the highly toxic topoisomerase inhibitor from Ir-liposomes was also accompanied by a high rate of toxicity in the bone marrow, liver, and intestines in animal studies, which is quite different from the protective effect of Ir-LB-MSNPs. Thus, despite the morphological resemblance to liposomes, the LB-MSNP carrier provides clear advantages over liposomal irinotecan delivery, from both efficacy and drug toxicity perspectives.

The bone marrow and the intestinal toxicity reduction by Ir-LB-MSNP is noteworthy from the perspective that the recently FDA-approved MM-398 liposomal formulation, Onivyde, is marketed with a black box warning of possible severe neutropenia and diarrhea during treatment of PDAC patients.17, 18 The warning states that fatal neutropenic sepsis was observed in 0.8% of patients, while severe or life-threatening neutropenic fever occurred in 3%.18 Life-threatening neutropenia was observed in 20% of patients receiving Onivyde in combination with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin.18 The same drug combination also caused severe diarrhea in 13% of treated subjects.18 Although we did not use Onivyde for comparison, an in-house liposomal formulation using TEA8SOS for irinotecan loading was associated with significant bone marrow and intestinal toxicity, similar to the free drug. Similar effects were not seen during treatment with the Ir-LB-MSNP platform.

It is interesting that both the MSNP and liposomal carriers are sequestered by KCs in the liver, as demonstrated by confocal microscopy using NIR-labeled particles and FITC-labeled anti-anti-F4/80 antibodies (not shown). While it is difficult to provide a direct in vivo demonstration, we propose that the disintegration of the LB and irinotecan release commence in acidic endo/lysosomal compartments in the KC.61–63 The more rapid disintegration of the liposomes could explain why only sparse NIR-labeled particles are seen in animals injected with Ir-liposomes compared to the presence of abundant Ir-LB-MSNP (Figure 2B). The rate of carrier disintegration could, in turn, determine the rate of drug release to bystander hepatocytes. This raises the possibility that irinotecan burst release from the liposomal carrier could overwhelm the hepatic metabolism of the drug, which is carried out by CYP 3A and uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1).64 Decreased metabolism could lead to higher retention of nonmetabolized drug, which leads to hepatocyte injury and necrosis, as shown in Figure 4A. This could explain the significantly higher content of nonconjugated irinotecan in the liver tissue of animals treated with Ir-liposomes compared to Ir-LB-MSNP, that is, 26 vs 15%ID/g at 24 h post IV injection (Figure S6). These findings are also compatible with the IHC staining of KC and activated caspase-3, which demonstrates a high cell death rate in KC and adjacent hepatocytes during treatment with Ir-liposomes, compared to the absence of apoptosis in Ir-LB-MSNP treated animals (Figure 4B). The schematic in Figure 4E outlines our hypothesis regarding the role of carrier stability and the rate of irinotecan release from KC in determining the extent of hepatocyte apoptosis and necrosis.65 It was not possible to measure hepatic enzymes, due to the limited amount of blood that could be obtained from the animals in their moribund state.

GEM frequently serves as first-line therapy for PDAC, with a survival outcome of 6.8 months.66, 67 While FOLFIRINOX can improve the survival to ~11 months, the frequent occurrence of serious drug toxicity (mostly due to irinotecan and oxaliplatin) precludes its use as first-line therapy. Thus, FOLFIRINOX is often reserved for patients with good performance status. Unfortunately, this position has not changed with the introduction of Onivyde, which is not approved as first-line therapy and includes black box warnings of severe diarrhea and neutropenia. Since approximately 80% of PDAC patients present at an advanced stage of disease, it would be advantageous to use drugs in the FOLFIRINOX regimen as first-line treatment. Although we have not used Onivyde for comparative analysis, the Ir-LB-MSNP platform was more efficacious and biocompatible with lower systemic toxicity than our equivalent in-house Ir-liposomal formulation. We propose, therefore, that the Ir-LB-MSNP platform could be developed for first-line therapy in PDAC. It is also feasible to consider the development of a MSNP nanocarrier for oxaliplatin, as well as the possibility that such a carrier could co-deliver irinotecan. We have recently demonstrated the feasibility of a dual delivery MSNP carrier for GEM and PTX in a PDAC model.32 Each treatment approach should carefully consider the design complexity, cost and impact on good manufacturing practice before implementation.68

Although the lipid-coated MSNPs have been shown to be efficacious for cargo delivery in vitro and/or in vivo, 32, 38, 56, 69, 70 this is the first demonstration of how a protonating agent can be used to increase the loading efficiency of this carrier platform. We have also identified a comprehensive list of weak basic drugs that can be loaded into LB-MSNPs through a proton gradient. The general characteristics of these cargo molecules include the following chemical properties: (i) organic molecular compounds that include primary, secondary, tertiary, or quaternary amine(s); (ii) a pKa <11 to allow protonation and entrapment behind the LB;71–73 (iii) a water solubility ranging from around 5 to 25 mg/mL and amphipathic characteristics that allow diffusion across the LB; (iv) an octanol/water partition coefficient or log P value of −3.0 to 3.0;71, 72 (v) suitable molecular weight with a geometric size less than MSNP pore size (2–8 nm) to allow entry into the MSNP pores.26, 27, 29 Without being all-inclusive, the list of potential chemotherapy agents include the topoisomerase I inhibitor, topotecan; the antitumor anthracycline antibiotics, doxorubicin and mitoxantrone; the mitotic inhibitors, vinblastine and vinorelbine; the tyrosine-kinase inhibitors imatinib, osimertinib and sunitinib, etc. The ability to package and deliver one or a combination of the above agents will enhance the wider utility of our multifunctional LB-MSNP platform, including treatment consideration of additional cancer types such as colon, breast, lung, liver, glioma, melanoma, etc. It is also possible to co-package drug combinations in the above list into a single carrier. For example, based on the success that we have achieved with our GEM/PTX co-delivery platform,32 it is possible to consider combining drugs in the FOLFIRINOX regimen (e.g., oxaliplatin with irinotecan) for synergistic and ratiometric delivery. Moreover, drug loading by our LB-MSNP can be used for noncancerous applications, such as encapsulating antibiotics for infectious diseases, for example, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin or HIV anti-retrovirals (e.g., tenofovir disoproxil fumarate). It is also worth pointing out that, in addition to TEA8SOS, transmembrane pH gradients can also be generated by acidic buffers (e.g., citrate),5, 74 proton-generating dissociable salts (e.g., (NH4)2SO4),39, 75, 76 or ionophore-mediated ion gradients from metal salts (e.g., A23187 and MnSO4).7, 11, 77 Moreover, it is possible to generate reverse pH gradients for drug loading, such as use a calcium acetate gradient to improve amphiphilic weak acid loading in LB-MSNP, a strategy that has been utilized in liposomes.78

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have developed a MSNP delivery platform for irinotecan, which, in spite of its morphological resemblance to a liposome, provides biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy superior to an equivalent liposomal formulation or free drug. The new carrier could be used to advance irinotecan delivery and drug combinations in the FOLFIRINOX regimen to first-line treatment status for PDAC.

METHODS

Materials

Tetraethylorthosicate (TEOS), triethanolamine, cetyltrimethylammonium chloride solution (CTAC, 25 wt% in water), triethylamine (TEA), Dowex 50WX8 resin, Sepharose CL-4B, and Sephadex G-25 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt) (DSPE-PEG2000), and cholesterol (Chol) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, USA. Sucrose octasulfate (SOS) sodium salt was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc, Canada. Irinotecan hydrochloride trihydrate was purchased from LC Laboratories, USA. Penicillin, streptomycin, and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) were obtained from Invitrogen. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gemini Bio Products. A rabbit mAb antibody (catlog. #9664) that detects activated (cleaved) caspase-3 was purchased from Cell Signaling. Matrigel™ Matrix Basement Membrane was purchased from BD Bioscience. Centrifugal filter units (cutoff size: 10K & 30K) were purchased from EMD Millipore. All chemicals were directly used without further purification.

Preparation of irinotecan loaded LB-MSNP, using a trapping reagent

Synthesis of MSNP

MSNP cores were synthesized by slight modification of our previous sol/gel procedure.32 To synthesize a batch of ~500 mg of MSNP, 50 mL of CTAC was mixed with 150 mL of H2O in a 500 mL conical flask, followed by stirring at 350 rpm for 15 min at 85 °C. This was followed by the addition of 8 mL of 10% triethanolamine for 30 min at the same temperature. Then, 7.5 mL of the silica precursor, TEOS, was added drop-wise at a rate of 1 mL/min using a peristaltic pump. The solution was stirred at 350 rpm at 85 °C for 20 min, leading to the formation particles with primary size of ~65 nm. The surfactant was removed by washing the particles with a mixture of methanol/HCl (500:19 v/v) at room temperature for 24 h. The particles were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 60 min and washed 3 times in methanol.

Synthesis of trapping agent TEA8SOS

TEA8SOS was synthesized from a commercially available SOS sodium salt by ion-exchange chromatography.8 Briefly, 500 mg of the salt was dissolved in 1 mL of deionized (DI) water, yielding an aqueous solution of 500 mg/mL. The solution was passed through an 8 cm × 1.5 cm cationic ion -exchange resin (Dowex 50WX8)column, prepared in DI water. The SOS salt was added to the column and eluted with the water for conversion to sucrose octasulfonic (SOS) acid. The acidic SOS eluate was titrated immediately with neat triethylamine to reach a final pH of 5.8. This resulted in the formation of the TEA8SOS. The salt concentration was adjusted to ~80 mM and stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator before use.

TEA8SOS loading and entrapment by a LB in MSNP

We used a novel method for entrapment of TEA8SOS in MSNP through the use of LB coating.32 The synthesis commenced by soaking 100 mg of empty MSNPs in 4 mL of an aqueous 80 mM TEA8SOS by probe sonication for 5 min, with a 15/15 s on/off working cycle and a power output of 32.5 W. The particle suspension was added immediately to a coated lipid biofilm, obtained by adding a mixture of 110 mg of DSPC/Chol/DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 3:2:0.15), suspended in chloroform at 10 mg/mL, to the bottom of a 6 cm round bottom flask. Following solvent evaporation in a rotary evaporator at room temperature, we obtained a biofilm with ~30 cm2 surface area. Following the addition of the particle suspension to the biofilm, probe sonication was used for 30 min with a 15/15 s on/off working cycle, at a power output of 32.5 W. Unentrapped TEA8SOS was removed by size exclusion chromatography over a Sepharose CL-4B column (1.5 × 15 cm), using a HEPES-buffered dextrose solution (5 mM HEPES, 5% dextrose, pH 6.5)for elusion.

Use of TEA8SOS-loaded LB-MSNP for irinotecan loading

Irinotecan was dissolved in HEPES buffered dextrose (5 mM HEPES, 5% dextrose, pH 6.5) at 10 mg/ml, which was mixed with the TEA8SOS-loaded particles to achieve an irinotecan/MSNP ratio of 1:1 (w/w). The mixture was incubated at 65 °C in a water bath for 30 min and then quenched in ice water for 10 min. The drug loaded particles were washed and purified 3 times by centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 10 min. The washed particles were resuspended in water, saline or PBS as indicated.

Preparation of a comparative liposomal formulation for irinotecan delivery

Irinotecan encapsulation by LB-MSNP, in the absence of a trapping agent

Empty MSNPs (40 mg) were added to 4 mL of a 10 mg/mL irinotecan solution (in water) with sonication, followed by stirring for 4 h at room temperature. The drug was then encapsulated by a LB, using sonication of lipid biofilm of similar composition as described above. After probe sonication, the particles were purified by centrifugation and washing and resuspended as described above.

Liposomal encapsulation of irinotecan, using TEA8SOS

In order to develop an in-house analog of the MM-398 formulation,8, 79 212 mg of a lipid mixture containing DSPC/Chol/DSPE-PEG2000 (at a molar ratio of 3:2:0.015) was dissolved in 0.4 mL of ethanol at 65 °C. Four milliliters of a TEA8SOS solution (80 mM) was mixed with the lipid ethanol solution at the same temperature, followed by sonication in a water bath for 2 min. The lipid suspension was extruded 15 times through a polycarbonate membrane with a 0.1 μm pore size at 65 °C. Unentrapped TEA8SOS was removed by a size exclusion chromatography column (Sepharose CL-4B), eluted with a HEPES-buffered dextrose solution (5 mM HEPES, 5% dextrose, pH 6.5). An irinotecan solution, prepared at 10 mg/mL in HEPES buffered dextrose (5 mM HEPES, 5% dextrose, pH 6.5), was mixed with TEA8SOS-loaded liposomal suspension (irinotecan: lipids = 1: 2.1, w/w), and incubated in a water bath at 65 °C for 30 mins. The sample was immediately quenched in ice water for 10 mins. The free drug was removed using a Sephadex G-25 column eluted with HEPES buffered saline (5 mM HEPES, 145 mM NaCl, pH 6.5).

Synthesis of an irinotecan liposomal carrier in the absence of a trapping agent

We also synthesized an irinotecan delivering liposome that uses a passive encapsulation approach, instead of using an entrapment agent. Briefly, a mixture of lipids (53 mg lipids, DSPC/Chol/DSPE-PEG2000 at molar ratio of 3:2:0.015) was dissolved in 0.1 mL of ethanol at 65 °C. One milliliter of an irinotecan solution (10 mg/mL in water) was mixed with the lipid ethanol solution at 65 °C, followed by sonication for 2 min. The lipid suspension was extruded 15 times through a polycarbonate membrane with a 0.1 μm pore size at 65 °C. The drug-laden liposome was purified using the same method as described above.

Physicochemical characterization

All particles used in this paper were extensively characterized for morphology, size, size distribution, shape and surface charge. The uniformity of LB coating and its intactness were characterized by TEM (JEOL 1200-EX) and cryoEM (TF20 FEI Tecnai-G2). Particle size and ζ-potential were measured by a ZETAPALS instrument (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation). These measurements were performed with the nanoparticles suspended in water, PBS, and cell culture media plus 10% FBS at a particle concentration of 100 μg/mL.

The drug loading capacity of each carrier was determined by a subtraction method, as described previously.32 Briefly, the amount of non-encapsulated irinotecan detected during purification (m1) was determined by OD (360 nm) in a microplate reader (M5e, Molecular Device, USA) or through the use of HPLC (Raytest, Germany). Drug loading capacity was defined as DLC= [the total amount of irinotecan (m0) non-encapsulated irinotecan (m1)]/[the total amount of particle (mMSNP or mlipid)]×100%. The drug retention stability was tested in 100% FBS at 37 °C for 24 h. Briefly, 40 μL of drug loaded NPs (irinotecan: 10 mg/mL) was added to 1 mL of serum at 37 °C, with continuous shaking. The mixture was centrifuged at set time intervals, using a centrifugal filter separation device (MW cutoff of 10K). The released irinotecan was quantified in a microplate reader or by HPLC. A serum filtrate without NPs was used as control. The stability of both carriers was also tested through a lyophilization procedure. Briefly, Ir-MSNPs were suspended in 5% dextrose. The sample was lyophilized at −60 °C overnight and stored in a −80 °C freezer. The stored samples were resuspended in water by gentle vortexing, following which the suspended solutions were characterized for size, ζ-potential, and drug release as described previously.

Cell culture

An immortalized cell line derived from a spontaneously developed tumor in a transgenic KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53LSL-R172H/+; Pdx-1-Cre mouse was kindly provided by Dr. Andrew Lowy at UC San Diego. PANC-1 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Both cell types were cultured in DMEM, containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. To allow bioluminescence tumor imaging in an IVIS system, both cells were permanently transfected with a luciferase-based lentiviral vector in the UCLA vector core facility, as previously described.32 Following a limiting dilution protocol to select single cell clones, the KPC-luc and PANC-1-luc cell populations were used to develop PDAC models.

Assessment of maximum tolerated dose (MTD)

The MTDs of free and encapsulated irinotecan formulations were determined using a protocol from the Toxicology and Pharmacology Branch (dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/tpb/default.htm) at the National Cancer Institute.8 Two healthy male BALB/c mice were IV injected with a 50 mg/kg (C1 dose) equivalent of free or encapsulated irinotecan. This was followed by a dose escalation factor of 1.8 to obtain the Cn dose, which results in animal death within 24 hrs after the last administration. The 2nd round of dose-seeking began with the Cn-1 dose and utilized a 1.15 escalation factor (n=2) to find the MTD, which is defined as the absence of mortality or morbidity. The MTD was validated by injecting 6 mice, which were followed for 15 days to determine absence of morbidity, mortality, or >15% weight loss.

Establishment of a KPC-derived orthotopic tumor model in immunocompetent mice

Female B6/129 mice (~8 weeks) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained under pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were performed with protocols approved by the UCLA Animal Research Committee. To grow orthotopic xenografts, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, followed by IP injection of 50 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. The surgical site was shaved to leave a margin of 1 cm around the incision site and sterilized by scrubbing with betadine and 70% ethanol. The mice were positioned for surgery on a heating pad, and the incision site in the left flank was draped with sterile gauze. A surgical incision of 0.5–0.7 cm was made to expose the pancreatic injection site, followed by an injection of 50 μL of DMEM/Matrigel (1:1 v/v) containing 2×106 KPC-luc cells into the pancreatic tail by a 27 gauge needle. The fascial layers were closed with absorbable sutures (PDS II, Ethicon) and the skin with nonabsorbable sutures (PROLENE, Ethicon). The mice were kept on the warming pads until full recovery from the anesthesia, and then transferred to clean cages. The efficacy study was performed in tumor-bearing mice approximately 2 weeks after implantation, at which point the primary tumors had grown to ~0.5 cm, without evidence of macroscopic tumor metastasis. For the biodistribution experiments, the tumor-bearing mice were used 3 weeks after tumor implantation, at which point the primary tumors had grown to a size of ~0.8 cm.

Systemic and intratumoral biodistribution of IV injected NIR labeled nanoparticles

An IVIS (Xenogen) in vivo imaging system was used to study the biodistribution of NIR-labeled MSNPs and liposomes in the KPC-derived orthotopic model (n=3 mice). NIR labeling was performed by incorporating 0.1% w/w Dylight 680-DMPE in the LB of both the liposomal and MSNP carriers without drug.32 For bioluminescence imaging of the tumor site, mice were injected IP with 75 mg/kg D-Luciferin. Reference fluorescence images for the tumor-bearing mice were captured before particle injection. NIR images were obtained over 48 h in animals IV injected with 100 mg/kg NIR-labeled particles. Following animal sacrifice, ex vivo images were obtained of excised tumors and major organs to quantitatively assess particle biodistribution. A small section of the tumor tissue was cryo-embedded, using the OCT reagent, and used to prepare tumor sections. The intratumoral distribution of the NIR-labeled particles was studied by confocal microscopy (SP2-1P-FCS, Leica), using a NIR laser. Nuclear staining of the same sections was performed by using Hoechst 33342 dye (blue). In animals treated with LB-MSNP, the tumor tissue and major organs were also used to assess the Si content by ICP-OES. Particle biodistribution was expressed as the % total injected dose (%ID) that could be shown to distribute to individual organs. In order to measure the irinotecan content in the tumor or other normal tissues, animals were injected with 60 mg/kg free or encapsulated irinotecan (particle dose, 120 mg/kg for MSNPs and 150 mg/kg for liposomes), followed by sacrifice after 24 hrs. HPLC analysis was performed on harvested tumor tissue, liver, spleen, kidney, intestines, and blood to determine irinotecan content.

HPLC analysis

The harvested tumor and organ samples were weighed and homogenized on ice. Following the extraction of 0.1 mL plasma or tissue homogenate with 0.4 mL of an acidic solution (0.1 mol/L phosphoric acid/methanol, 1:4 v/v), the extracts were vortexed twice for 10 s and centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 10 min. The irinotecan-containing supernatants were filtrated through 0.22 μm filters for HPLC analysis in a system containing a Knauer Smartline pneumatic pump, C18 column, K-2600 spectrophotometer and Gina data acquisition software. The mobile phase, delivered at a flow rate of 1.00 mL/min, comprised a 3% triethylammonium acetate aqueous buffer (pH=5.5) and acetonitrile (73:27 v/v).80 Twenty microliters irinotecan-containing sample was injected to measure the drug absorption at 254 nm, typically eluted in 4.4 min. An irinotecan standard curve was generated over the concentration range 0.05–100 μg/mL. Irinotecan content was expressed as % of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

Efficacy assessment using the KPC-derived orthotopic model

Tumor-bearing B6/129 mice were randomly assigned to 4 groups, e.g., including 8 animals per group. The mice were IV injected with free or encapsulated irinotecan to receive a dose of 40 mg/kg (i.e., a liposomal dose of 100 or 80 mg/kg MSNP) every 4 days. A maximum of eight injections were administered over a 28-day observation period. Saline injections served as a negative control. Tumor burden was monitored by IVIS imaging every 8 day and quantitatively expressed as bioluminescence imaging intensity in the operator-defined ROI. The statistical analysis of the differences between the groups was performed using a t-test (Excel software, Microsoft). All surviving mice were sacrificed at day 47, at which point all animals in the saline and drug-free group had died. The tumor tissue and major organs (GI tract, liver, spleen, heart, lung and kidneys) were harvested for quantification of ex vivo bioluminescence image intensity.

Comparison of the toxicity potential of different irinotecan formulations

Major tissues collected during the efficacy testing experiment (liver, kidney, spleen, stomach and intestines) were fixed in 10% formalin, followed by paraffin embedding. Tissue sections were stained by H&E for histological analysis and also used for IHC analysis of the expression of activated (cleaved) caspase-3. The slides were read in a blinded fashion by an experienced veterinary pathologist. The second approach for assessing bone marrow toxicity used three IV administrations, 2 days apart, of free drug and carrier formulations at 40 mg/kg in healthy mice. The animals were sacrificed on day 7, and the sternum was used for fixation in 10% formalin, decalcification, paraffin embedding and H&E staining. We also collected blood for differential white cell counting by the UCLA Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine (DLAM) diagnostic laboratory services.

To understand the mechanism of differential liver toxicity by free drug and the carriers, mice receiving a single injection of the dose equivalent of 60 mg/kg irinotecan were sacrificed after 24 h. The liver tissues were cryo-embedded for immunofluorescence staining of KCs and the expression of activated caspase-3, using a FITC-labeled anti-F4/80 antibody or a RITC-conjugated secondary antibody to identify KC and cleaved caspase-3, respectively. Hoechst 33342 dye was used to localize the cellular nuclei in the same sections. The stained slides were examined under a confocal microscope (Observer D1, Zeiss).

Statistical analysis

Comparative analysis of the differences between groups was performed using the two-sided Student’s t-test (Excel software, Microsoft). A statistically significant difference was determined at p < 0.05. Values were expressed as mean± SD or SEM of multiple determinations, as stated in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the U.S. Public Health Service Grant 1U01CA198846. The project also received partial support by the Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research. We acknowledge gifts of the KPC-derived cells by Dr. Andrew Lowy (UC San Diego) and AML12 cells by Dr. Harvey R. Herschman (UCLA). The authors thank the CNSI Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Facility at UCLA for confocal fluorescent microscopy and the use of TEM instruments at the Electron Imaging Center for NanoMachines.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Additional figures, table, and results as described in the text.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge online.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, Péré-Vergé D, Delbaldo C, Assenat E, Chauffert B, Michel P, Montoto-Grillot C, Ducreux M. FOLFIRINOX versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. New Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueno H, Okusaka T, Funakoshi A, Ishii H, Yamao K, Ishikawa O, Ohkawa S, Saitoh S. A Phase II Study of Weekly Irinotecan as First-Line Therapy for Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 2007;59:447–454. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loupakis F, Schirripa M, Caparello C, Funel N, Pollina L, Vasile E, Cremolini C, Salvatore L, Morvillo M, Antoniotti C. Histopathologic Evaluation of Liver Metastases from Colorectal Cancer in Patients Treated with FOLFOXIRI plus Bevacizumab. Brit J Cancer. 2013;108:2549–2556. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou TH, Chen SC, Chu IM. Effect of Composition on the Stability of Liposomal Irinotecan Prepared by a pH Gradient Method. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;95:405–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onishi H, Machida Y, Machida Y. Antitumor Properties of Irinotecan-Containing Nanoparticles Prepared Using Poly (DL-Lactic Acid) and Poly (Ethylene Glycol)-Block-Poly (Propylene Glycol)-Block-Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:116–119. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messerer CL, Ramsay EC, Waterhouse D, Ng R, Simms EM, Harasym N, Tardi P, Mayer LD, Bally MB. Liposomal Irinotecan Formulation Development and Therapeutic Assessment in Murine Xenograft Models of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6638–6649. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drummond DC, Noble CO, Guo Z, Hong K, Park JW, Kirpotin DB. Development of A Highly Active Nanoliposomal Irinotecan Using a Novel Intraliposomal Stabilization Strategy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3271–3277. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valencia PM, Pridgen EM, Perea B, Gadde S, Sweeney C, Kantoff PW, Bander NH, Lippard SJ, Langer R, Karnik R. Synergistic Cytotoxicity of Irinotecan and Cisplatin in Dual-Drug Targeted Polymeric Nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:687–698. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadzuka Y, Hirotsu S, Hirota S. Effect of Liposomalization on the Antitumor Activity, Side-Effects and Tissue Distribution of CPT-11. Cancer Lett. 1998;127:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay E, Alnajim J, Anantha M, Zastre J, Yan H, Webb M, Waterhouse D, Bally M. A Novel Liposomal Irinotecan Formulation with Significant Anti-Tumour Activity: Use of the Divalent Cation Ionophore A23187 and Copper-Containing Liposomes to Improve Drug Retention. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;68:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Zhao X, Wang H, Zhao R, Ji T, Ren H, Anderson GJ, Nie G, Hao J. Multiple Layer-by-Layer Lipid-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles for Improved FOLFIRINOX Chemotherapy in Pancreatic Tumor Models. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:788–798. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu DZ, Chen WY, Tasi LM, Yang SP. Microcalorimetric and Shear Studies on the Effects of Cholesterol on the Physical Stability of Lipid Vesicles. Colloid Surface A. 2000;172:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heurtault B, Saulnier P, Pech B, Proust JE, Benoit JP. Physico-Chemical Stability of Colloidal Lipid Particles. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4283–4300. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabın J, Prieto G, Ruso J, Hidalgo-Alvarez R, Sarmiento F. Size and Stability of Liposomes: a Possible Role of Hydration and Osmotic Forces. Eur Phys J E. 2006;20:401–408. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2006-10029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Hoff D, Li C, Wang-Gillam A, Bodoky G, Dean A, Jameson G, Macarulla T, Lee K, Cunningham D, Blanc J. NAPOLI 1: Randomized Phase 3 Study of MM-398 (nal-IRI), with or without 5-Fluorouracil and Leucovorin, versus 5-Fluorouracil and Leucovorin, in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Progressed on or following Gemcitabine-Based Therapy. Brit J Cancer. 2013;109:920–925. [Google Scholar]

- 17. [accessed October 22, 2015]; http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm468654.htm.

- 18. [accessed October 23, 2015]; http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/207793lbl.pdf.

- 19.Lu J, Liong M, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as a Delivery System for Hydrophobic Anticancer Drugs. Small. 2007;3:1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slowing II, Vivero-Escoto JL, Wu C-W, Lin VS-Y. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as Controlled Release Drug Delivery and Gene Transfection Carriers. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2008;60:1278–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, Zhao YL, Tamanoi F, Stoddart JF, Zink JI, Nel AE. Autonomous In Vitro Anticancer Drug Release from Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles by pH-Sensitive Nanovalves. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12690–12697. doi: 10.1021/ja104501a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CH, Cheng SH, Huang I, Souris JS, Yang CS, Mou CY, Lo LW. Intracellular pH-Responsive Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for the Controlled Release of Anticancer Chemotherapeutics. Angew Chem. 2010;122:8390–8395. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, Ji Z, Tarn DY, Zink JI, Nel AE. Use of Size and a Copolymer Design Feature to Improve the Biodistribution and the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect of Doxorubicin-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles in a Murine Xenograft Tumor Model. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4131–4144. doi: 10.1021/nn200809t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He Q, Shi J. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Based Nano Drug Delivery Systems: Synthesis, Controlled Drug Release and Delivery, Pharmacokinetics and Biocompatibility. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:5845–5855. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Y, Chen Y, Ji X, He X, Yin Q, Zhang Z, Shi J, Li Y. Controlled Intracellular Release of Doxorubicin in Multidrug-Resistant Cancer Cells by Tuning the Shell-Pore Sizes of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9788–9798. doi: 10.1021/nn2033105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles in Biomedical Applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2590–2605. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang F, Li L, Chen D. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Biocompatibility and Drug Delivery. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1504–1534. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng H, Mai WX, Zhang H, Xue M, Xia T, Lin S, Wang X, Zhao Y, Ji Z, Zink JI. Codelivery of An Optimal Drug/siRNA Combination Using Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles to Overcome Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer In Vitro and In Vivo. ACS Nano. 2013;7:994–1005. doi: 10.1021/nn3044066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarn D, Ashley CE, Xue M, Carnes EC, Zink JI, Brinker CJ. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Nanocarriers: Biofunctionality and Biocompatibility. Accounts Chem Res. 2013;46:792–801. doi: 10.1021/ar3000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng H, Zhao Y, Dong J, Xue M, Lin YS, Ji Z, Mai WX, Zhang H, Chang CH, Brinker CJ. Two-Wave Nanotherapy to Target the Stroma and Optimize Gemcitabine Delivery to a Human Pancreatic Cancer Model in Mice. ACS Nano. 2013;7:10048–10065. doi: 10.1021/nn404083m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Argyo C, Weiss V, Bra uchle C, Bein T. Multifunctional Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles As A Universal Platform For Drug Delivery. Chem Mater. 2014;26:435–451. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng H, Wang M, Liu H, Liu X, Situ A, Wu B, Ji Z, Chang CH, Nel AE. Use of a Lipid-Coated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Platform for Synergistic Gemcitabine and Paclitaxel Delivery to Human Pancreatic Cancer in Mice. ACS Nano. 2015;9:3540–3557. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu J, Liong M, Li Z, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Biocompatibility, Biodistribution, and Drug-Delivery Efficiency of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy in Animals. Small. 2010;6:1794–1805. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He Q, Shi J, Chen F, Zhu M, Zhang L. An Anticancer Drug Delivery System Based on Surfactant-Templated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3335–3346. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Jiang X, Ashley C, Brinker CJ. Electrostatically Mediated Liposome Fusion and Lipid Exchange with a Nanoparticle-Supported Bilayer for Control of Surface Charge, Drug Containment, and Delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7567–7569. doi: 10.1021/ja902039y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Stace-Naughton A, Jiang X, Brinker CJ. Porous Nanoparticle Supported Lipid Bilayers (Protocells) as Delivery Vehicles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1354–1355. doi: 10.1021/ja808018y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cauda V, Engelke H, Sauer A, Arcizet D, Radler J, Bein T. Colchicine-Loaded Lipid Bilayer-Coated 50 nm Mesoporous Nanoparticles Efficiently Induce Microtubule Depolymerization upon Cell Uptake. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2484–2492. doi: 10.1021/nl100991w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Li F, Guo S, Chen X, Wang X, Li J, Gan Y. Biofunctionalized Polymer-Lipid Supported Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Release of Chemotherapeutics in Multidrug Resistant Cancer Cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3650–3665. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haran G, Cohen R, Bar LK, Barenholz Y. Transmembrane Ammonium Sulfate Gradients in Liposomes Produce Efficient and Stable Entrapment of Amphipathic Weak Bases. BBA-Biomembranes. 1993;1151:201–215. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghanbarzadeh S, Valizadeh H, Zakeri-Milani P. The Effects of Lyophilization on the Physico-Chemical Stability of Sirolimus Liposomes. Adv Pharm Bull. 2013;3:25. doi: 10.5681/apb.2013.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, Rustgi AK, Chang S, Tuveson DA. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D Cooperate to Promote Chromosomal Instability and Widely Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma in Mice. Cancer cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tseng WW, Winer D, Kenkel JA, Choi O, Shain AH, Pollack JR, French R, Lowy AM, Engleman EG. Development of an Orthotopic Model of Invasive Pancreatic Cancer in an Immunocompetent Murine Host. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3684–3695. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Provenzano P, Hingorani S. Hyaluronan, Fluid Pressure, and Stromal Resistance in Pancreas Cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2013;108:1–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torres MP, Rachagani S, Souchek JJ, Mallya K, Johansson SL, Batra SK. Novel Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines Derived from Genetically Engineered Mouse Models of Spontaneous Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Applications in Diagnosis and Therapy. PloS One. 2013;8:e80580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida M, Takimoto R, Murase K, Sato Y, Hirakawa M, Tamura F, Sato T, Iyama S, Osuga T, Miyanishi K. Targeting Anticancer Drug Delivery to Pancreatic Cancer Cells Using a Fucose-Bound Nanoparticle Approach. PloS One. 2012;7:e39545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, Yin W, Zheng X, Tian G, Zhang X, Bao T, Dong X, Wang Z, Gu Z, Ma X. Smart MoS2/Fe3O4 Nanotheranostic for Magnetically Targeted Photothermal Therapy Guided by Magnetic Resonance/Photoacoustic Imaging. Theranostics. 2015;5:931–945. doi: 10.7150/thno.11802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Mizuno K, Chen Q, Murakami M, Kimura M, Terada Y, Kano M, Miyazono K, Uesaka M. Accumulation of Sub-100 nm Polymeric Micelles in Poorly Permeable Tumours Depends on Size. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:815–823. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo J, Hong H, Chen G, Shi S, Zheng Q, Zhang Y, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W, Gong S. Image-Guided and Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery with Radiolabeled Unimolecular Micelles. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8323–8332. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J, Gattacceca F, Amiji M. Biodistribution and Pharmacokinetics of EGFR-Targeted Thiolated Gelatin Nanoparticles Following Systemic Administration in Pancreatic Tumor-Bearing Mice. Mol Pharmaceut. 2013;10:2031–2044. doi: 10.1021/mp400054e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ziegler U, Groscurth P. Morphological Features of Cell Death. Physiology. 2004;19:124–128. doi: 10.1152/nips.01519.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.King PD, Perry MC. Hepatotoxicity of Chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2001;6:162–176. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-2-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maor Y, Malnick S. Liver Injury Induced by Anticancer Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy. Int J Hepatol. 2013;2013:815105. doi: 10.1155/2013/815105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iusuf D, Ludwig M, Elbatsh A, van Esch A, van de Steeg E, Wagenaar E, van der Valk M, Lin F, van Tellingen O, Schinkel AH. OATP1A/1B Transporters Affect Irinotecan and SN-38 Pharmacokinetics and Carboxylesterase Expression in Knockout and Humanized Transgenic Mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:492–503. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Travlos GS. Histopathology of Bone Marrow. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:566–598. doi: 10.1080/01926230600964706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng H, Liong M, Xia T, Li Z, Ji Z, Zink JI, Nel AE. Engineered Design of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles to Deliver Doxorubicin and P-Glycoprotein siRNA to Overcome Drug Resistance in a Cancer Cell Line. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4539–4550. doi: 10.1021/nn100690m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashley CE, Carnes EC, Phillips GK, Padilla D, Durfee PN, Brown PA, Hanna TN, Liu J, Phillips B, Carter MB, Carroll NJ, Jiang X, Dunphy DR, Willman CL, Petsev DN, Evans DG, Parikh AN, Chackerian B, Wharton W, Peabody DS, Brinker CJ. The Targeted Delivery of Multicomponent Cargos to Cancer Cells by Nanoporous Particle-Supported Lipid Bilayers. Nat Mater. 2011;10:389–397. doi: 10.1038/nmat2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang X, Mao G, Ng KS. Mechanical Properties and Stability Measurement of Cholesterol-Containing Liposome on Mica by Atomic Force Microscopy. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2004;278:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson TH, Min Y, Weirich KL, Zeng H, Fygenson D, Israelachvili JN. Formation of Supported Bilayers on Silica Substrates. Langmuir. 2009;25:6997–7005. doi: 10.1021/la900181c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michel R, Gradzielski M. Experimental Aspects of Colloidal Interactions in Mixed Systems of Liposome and Inorganic Nanoparticle and Their Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:11610–11642. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang F, Liu J. Liposome Supported Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Interaction Mechanism, Light Controlled Content Release, and Intracellular Delivery. Small. 2014;10:3927–3931. doi: 10.1002/smll.201400850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hwang KJ, Luk K, Beaumier PL. Hepatic Uptake and Degradation of Unilamellar Sphingomyelin/Cholesterol Liposomes: a Kinetic Study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4030–4034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Derksen J, Morselt H, Scherphof G. Uptake and Processing of Immunoglobulin-Coated Liposomes by Subpopulations of Rat Liver Macrophages. BBA-Mol Cell Res. 1988;971:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(88)90184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolter T, Sandhoff K. Lysosomal Degradation of Membrane Lipids. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mathijssen RH, van Alphen RJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Nooter K, Stoter G, Sparreboom A. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Irinotecan (CPT-11) Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2182–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao F, Meng H, Yan L, Wang B, Zhao Y. Nanosurface Chemistry and Dose Govern the Bioaccumulation and Toxicity of Carbon Nanotubes, Metal Nanomaterials and Quantum Dots. In Vivo Sci Bull. 2015;60:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burris Hr, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P. Improvements in Survival and Clinical Benefit with Gemcitabine as First-Line Therapy for Patients with Advanced Pancreas Cancer: a Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Teague A, Lim KH, Wang-Gillam A. Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: a Review of Current Treatment Strategies and Developing Therapies. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7:68–84. doi: 10.1177/1758834014564775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sugahara KN, Teesalu T, Karmali PP, Kotamraju VR, Agemy L, Greenwald DR, Ruoslahti E. Coadministration of a Tumor-Penetrating Peptide Enhances the Efficacy of Cancer Drugs. Science. 2010;328:1031–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.1183057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ashley CE, Carnes EC, Epler KE, Padilla DP, Phillips GK, Castillo RE, Wilkinson DC, Wilkinson BS, Burgard CA, Kalinich RM. Delivery of Small Interfering RNA by Peptide-Targeted Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Supported Lipid Bilayers. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2174–2188. doi: 10.1021/nn204102q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dengler EC, Liu J, Kerwin A, Torres S, Olcott CM, Bowman BN, Armijo L, Gentry K, Wilkerson J, Wallace J. Mesoporous Silica-Supported Lipid Bilayers (Protocells) for DNA Cargo Delivery to the Spinal Cord. J Control Release. 2013;168:209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zucker D, Marcus D, Barenholz Y, Goldblum A. Liposome Drugs’ Loading Efficiency: a Working Model Based on Loading Conditions and Drug’s Physicochemical Properties. J Control Release. 2009;139:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cern A, Golbraikh A, Sedykh A, Tropsha A, Barenholz Y, Goldblum A. Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship Modeling of Remote Liposome Loading of Drugs. J Control Release. 2012;160:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu H, Paxton J, Lim J, Li Y, Zhang W, Duxfield L, Wu Z. Development of High-Content Gemcitabine PEGylated Liposomes and Their Cytotoxicity on Drug-Resistant Pancreatic Tumour Cells. J Control Release. 2014;31:2583–2592. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nichols JW, Deamer DW. Catecholamine Uptake and Concentration by Liposomes Maintaining pH Gradients. BBA-Biomembranes. 1976;455:269–271. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maurer-Spurej E, Wong KF, Maurer N, Fenske DB, Cullis PR. Factors Influencing Uptake and Retention of Amino-Containing Drugs in Large Unilamellar Vesicles Exhibiting Transmembrane pH Gradients. BBA-Biomembranes. 1999;1416:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fritze A, Hens F, Kimpfler A, Schubert R, Peschka-Süss R. Remote Loading of Doxorubicin into Liposomes Driven by a Transmembrane Phosphate Gradient. BBA-Biomembranes. 2006;1758:1633–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fenske DB, Wong KF, Maurer E, Maurer N, Leenhouts JM, Boman N, Amankwa L, Cullis PR. Ionophore-Mediated Uptake of Ciprofloxacin and Vincristine into Large Unilamellar Vesicles Exhibiting Transmembrane Ion Gradients. BBA-Biomembranes. 1998;1414:188–204. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Avnir Y, Ulmansky R, Wasserman V, Even-Chen S, Broyer M, Barenholz Y, Naparstek Y. Amphipathic Weak Acid Glucocorticoid Prodrugs Remote-Loaded into Sterically Stabilized Nanoliposomes Evaluated in Arthritic Rats and in a Beagle Dog: a Novel Approach to Treating Autoimmune Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:119–129. doi: 10.1002/art.23230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ko A, Tempero M, Shan Y, Su W, Lin Y, Dito E, Ong A, Wang Y, Yeh C, Chen L. A Multinational Phase 2 Study of Nanoliposomal Irinotecan Sucrosofate (PEP02, MM-398) for Patients with Gemcitabine-Refractory Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2013;109:920–925. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Noble CO, Krauze MT, Drummond DC, Yamashita Y, Saito R, Berger MS, Kirpotin DB, Bankiewicz KS, Park JW. Novel Nanoliposomal CPT-11 Infused by Convection-Enhanced Delivery in Intracranial Tumors: Pharmacology and Efficacy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2801–2806. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.