Abstract

Primary cilia are solitary, generally non-motile, hair-like protrusions that extend from the surface of cells between cell divisions. Their antenna-like structure leads naturally to the assumption that they sense the surrounding environment, the most common hypothesis being sensation of mechanical force through calcium-permeable ion channels within the cilium1. This Ca2+- Responsive MechanoSensor (CaRMS) hypothesis for primary cilia has been invoked to explain a large range of biological responses, from control of left-right axis determination in embryonic development to adult progression of polycystic kidney disease and some cancers2,3. Here, we report the complete lack of mechanically induced calcium increases in primary cilia, in tissues upon which this hypothesis has been based. First, we developed a transgenic mouse, Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2, expressing a ratiometric genetically encoded calcium indicator (GECI) in all primary cilia. We then measured responses to flow in primary cilia of cultured kidney epithelial cells, kidney thick ascending tubules, crown cells of the embryonic node, kinocilia of inner ear hair cells, and several cell lines. Cilia-specific Ca2+ influxes were not observed in physiological or even highly supraphysiological levels of fluid flow. We conclude that mechanosensation, if it originates in primary cilia, is not via calcium signaling.

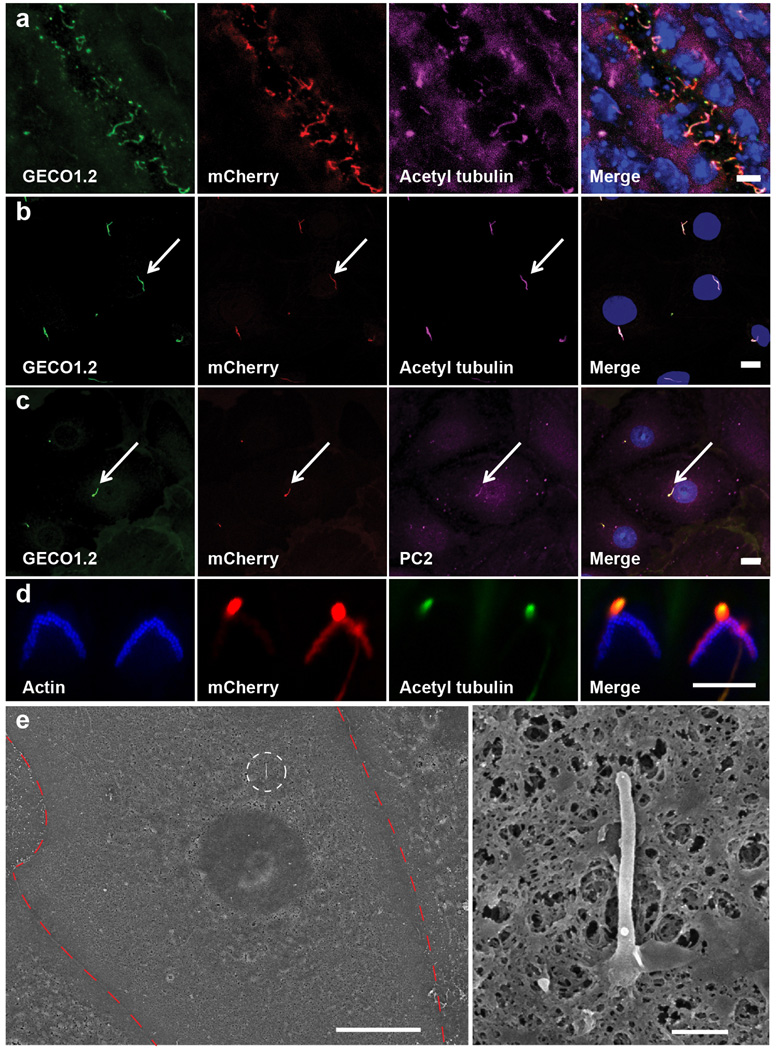

To examine ciliary Ca2+ signaling in vivo, we generated transgenic Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg mice in which fluorescent indicators are confined to the primary cilia (Fig. 1 a–c, Extended Data Fig. 1, 2). To accurately measure changes in [Ca2+] in small moving subcellular structures and control for motion artifacts and differential bleaching of ratioing dyes, we first examined hair cells in the cochlea’s organ of Corti, the most sensitive of known CaRMS4–6. The apical surface of each hair cell carries a hair bundle with staggered rows of specialized actin-based microvillar projections called ‘stereocilia’ (Extended Data Fig. 3). Adjacent to the tallest stereocilia is a single nonmotile, microtubule-based true cilium (9+2; kinocilium). Fine filamentous ‘tip links’ connect adjacent stereocilia and transmit force to mechano-electrical transduction (MET) channels. MET channels open in microseconds, and Ca2+ entry rapidly raises [Ca2+] in stereocilia (10–20 ms time constant) 7. Using hair cells from the Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg mouse, we can compare [Ca2+] changes in two structures (stereocilia and kinocilia) of similar geometry (4–10 µm length and 300–600 nm diameter), and determine whether the kinocilium is also a CaRMS, as suggested 8.

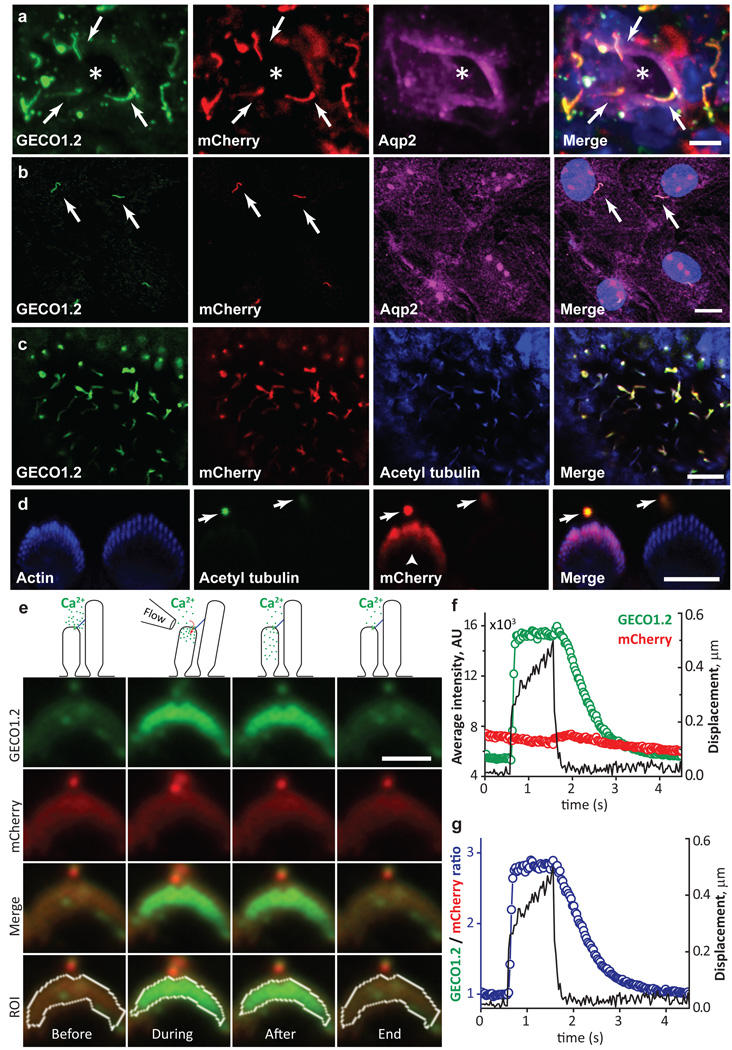

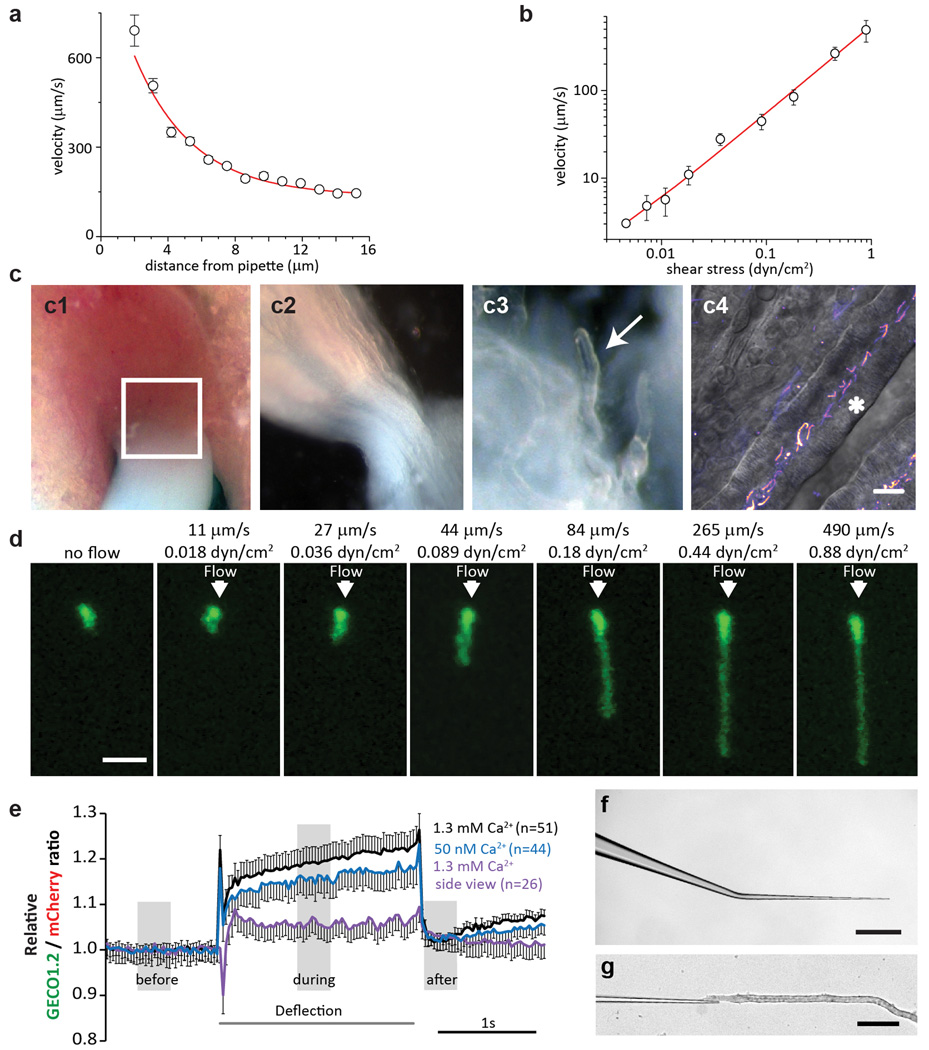

Figure 1. Genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator localizes to primary cilia and cochlear hair cell bundles.

a, P14 kidney section expressing Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 in primary cilia. Cilia (white arrows) point into the lumen of an aquaporin 2-positive tubule (*). Scale bar, 5 µm. b, Aqp2 in primary epithelial cells isolated and cultured (3 d.i.v.) from kidney papilla of P14-P21 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mice (Extended Data Fig. 1). Scale bar, 10 µm. c, Embryonic node from an Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg mouse. mCherry and GECO1.2 in cilia of the embryonic node overlap with the cilia marker, acetylated tubulin. Scale bar, 10 µm. d, Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 expression in IHCs. P4 organ of Corti explant showing two hair bundles; mCherry fluorescence (red), phalloidin-labeled actin (blue), and antibody to acetylated tubulin (green). Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 protein localizes to all kinocilia as demonstrated by overlapping acetylated tubulin staining (arrows). Later in development, Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 also localizes to stereocilia bundles of some IHCs and OHCs (mCherry-positive bundle, arrowhead; Extended Data Fig. 1). Scale bar, 5 µm. e–g, Deflection of IHC stereocilia bundle. ROI: white outline. e, GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence in stereocilia before, during, and after deflection. A 1s flow stimulus (Supplementary Video 1) increased GECO1.2 fluorescence as Ca2+ entered the shorter rows of stereocilia. Scale bar, 5 µm. f, GECO1.2 and mCherry average fluorescence intensities (A.U.) within the ROI; bundle displacement during deflection (black). Deflection increased GECO1.2 fluorescence 3-fold; mCherry bleached only slightly. g, Change of stereocilia F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratio during the deflection (blue symbols); bundle displacement, black. After stimulus, the bundle rapidly returned to its resting position while Ca2+ fluorescence decayed slowly (τ = 0.6 s; Extended Data Fig. 4a–b). Images acquired sequentially, 30 ms/paired frame. All images are representative of >10 images taken of biological triplicates.

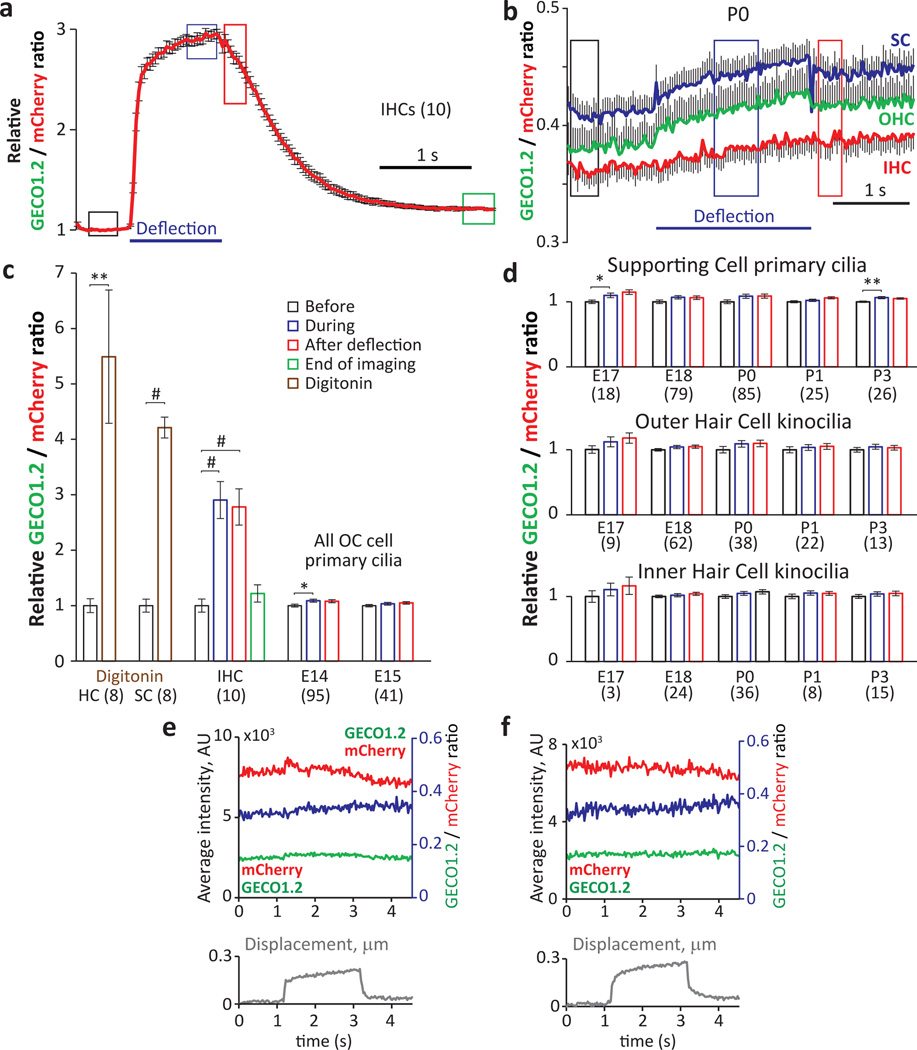

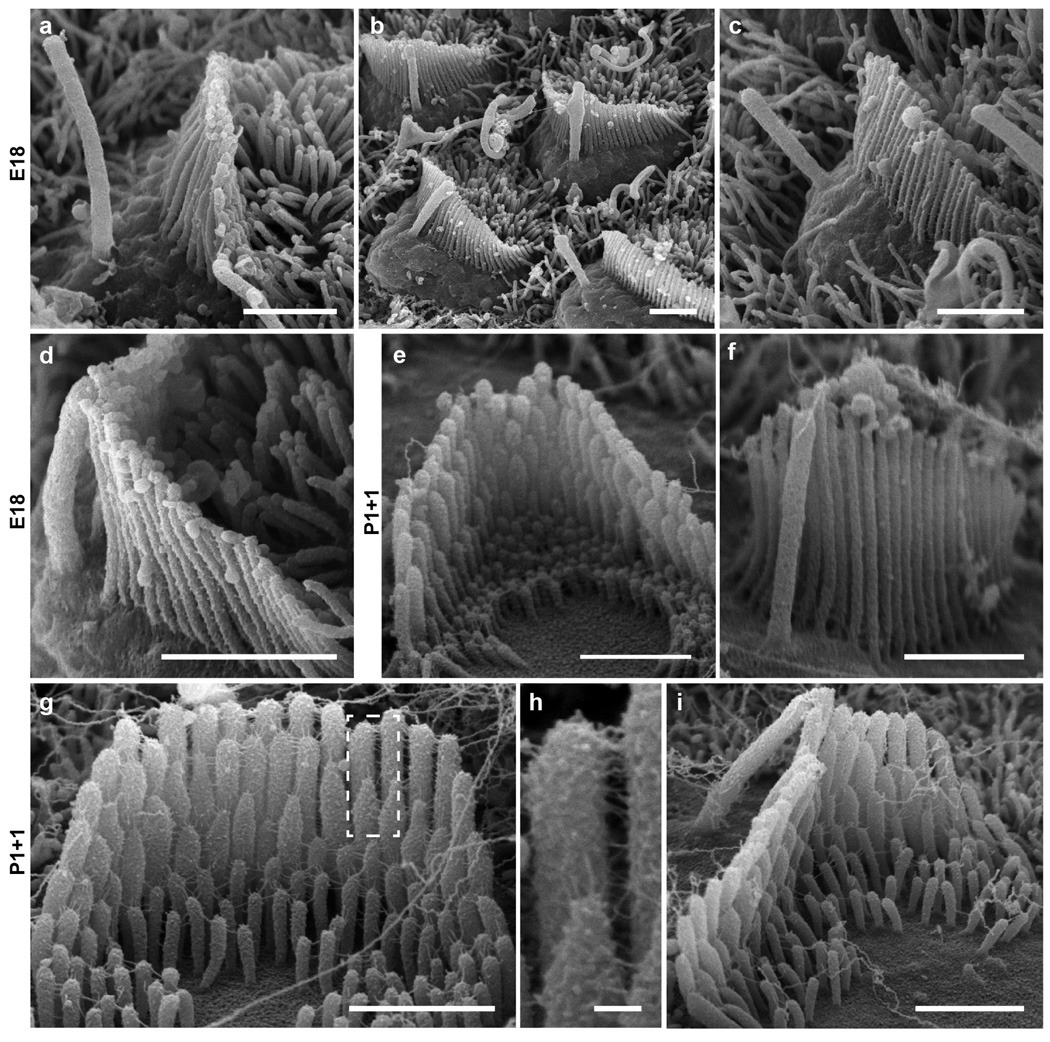

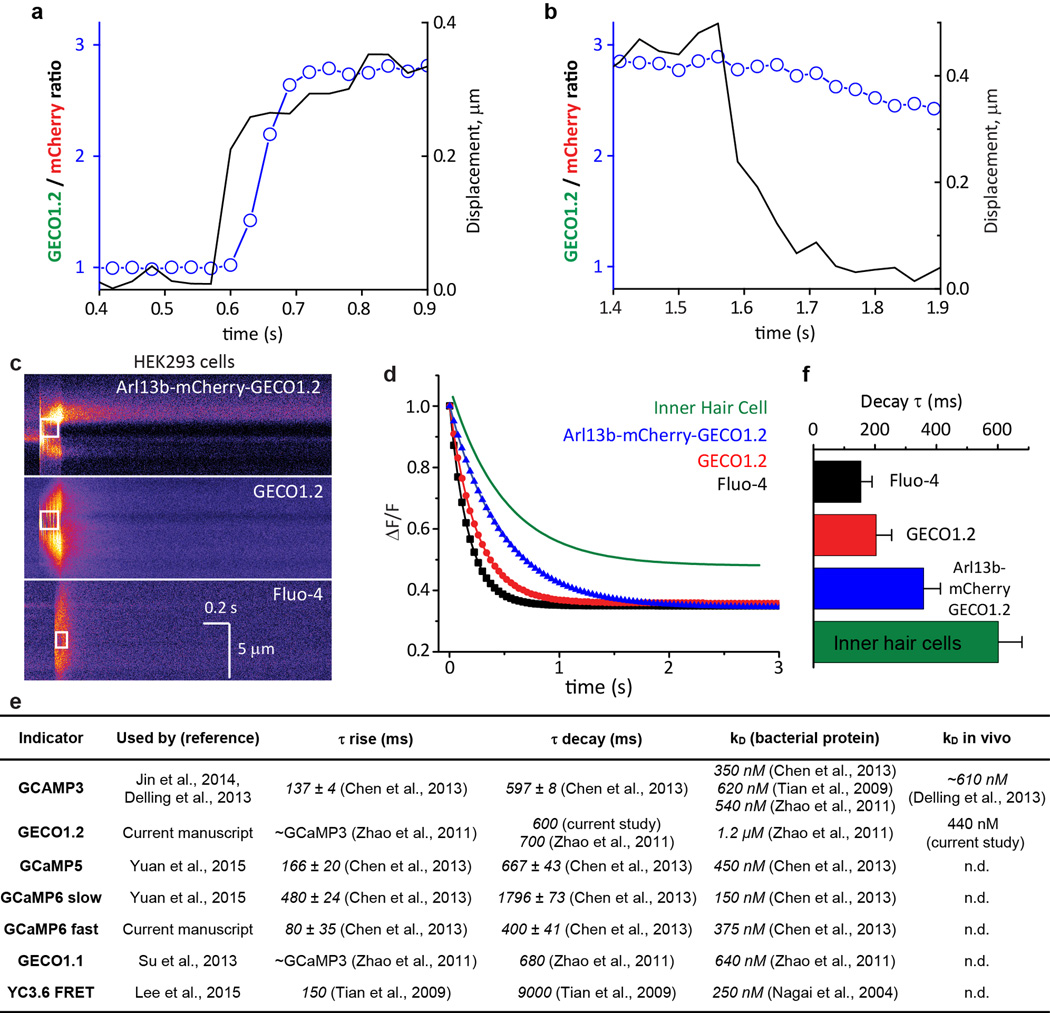

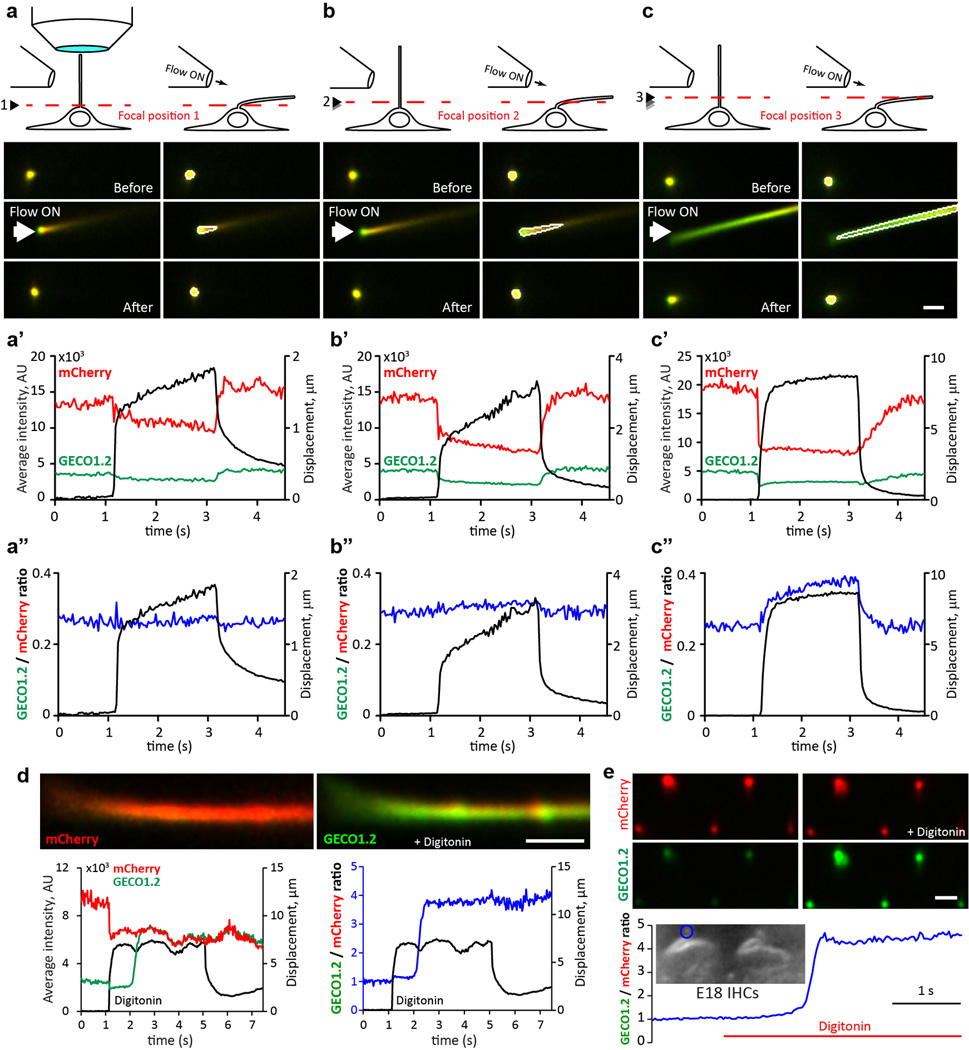

Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 is expressed in all primary cilia of the inner ear sensory epithelium, including kinocilia of both inner hair cells (IHCs) and outer hair cells (OHCs) of the organ of Corti. Scanning electron microscopy at ages E18 to P3 confirmed normal development of stereocilia bundles in transgenic animals (Extended Data Fig. 3). Fortuitously, some hair cell stereocilia also contained the Ca2+ indicator (Fig 1d, Extended Data Fig. 1d). To test for CaRMS, we applied laminar flow via a micropipette to IHC bundles (Supplementary Video 1) or kinocilia and imaged via swept field confocal microscopy (up to 1000 frames/s) to pinpoint the origin of Ca2+ influx with high spatial and temporal resolution. Ratioing of GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence (F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry) reduced movement-related artifacts (see Methods, Supplementary Information). As expected, deflection of the stereocilia bundle resulted in a rapid and robust increase in GECO1.2 fluorescence within the bundle, while mCherry fluorescence remained largely unchanged (Fig. 1e–g, Supplementary Video 1). IHC bundle deflection increased the ratio ~ 3-fold (Fig. 2a), slowly recovering to the resting value within 2.5 s after flow application. The slow dissociation rate of Ca2+ from GECO1.2 (τ ~600 ms, Extended Data Fig. 4) provides a valuable means to distinguish true changes in [Ca2+] from movement-related artifacts. In contrast, kinocilia deflected by pressure steps over a range of developmental stages (E14 to P3) exhibited no detectable increase in [Ca2+]cilium (Fig. 2b–f; Supplementary Information). We conclude that kinocilia of mouse hair cells, unlike actin-based stereocilia, are not CaRMS.

Figure 2. No change in [Ca2+]cilium in kinocilia of developing hair cells.

a, Average ratio changes in stereocilia for IHC bundle deflections in P5+3 d.i.v. organ of Corti explants (n in brackets). b, Average ratio changes for IHC kinocilia (red, n=36), OHC kinocilia (green, n=38) and supporting-cell (SC) primary cilia (blue; n=85). The small positive slope results from differential dye bleaching (mCherry > GECO1.2). c, Normalized average fluorescent ratio changes at times boxed in a and b. Digitonin applied locally to permeabilise the membrane evoked a ~5-fold ratio increase in hair cell kinocilia and SC primary cilia (brown bars). Black bar: normalized ratio before; blue bar: during; red bar: after application. IHC bundle deflection increased stereocilia ratios ~3-fold, persisting well after the bundle returned to its initial position. E14 and E15 explants showed no ratio change in any organ of Corti (OC) primary cilia. d, Kinocilia of IHC, OHC and SC, from E17 to P3, show no ratio change upon deflection. The slight variability of the ratios from the SC cilia (before, during, after) is similar to the variability of the ratios in IHC and OHC kinocilia. e, f, Individual IHC (e) and OHC (f) kinocilia at P0. GECO1.2 (green) and mCherry (red) intensities and their ratio (blue) shows no Ca2+ influx upon deflection. Kinocilium displacement in grey (bottom panel). Student’s t-test, * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, # = p<0.001. All error bars ± SEM.

Next, we examined kidney epithelia primary cilia, widely believed to be CaRMS1,3,9. Primary inner medullary collecting duct (mIMCD) epithelial cells were isolated from kidneys of P14-P21 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mice, which express the kidney collecting duct epithelial cell marker, Aquaporin2 (Aqp2; Fig. 1b) and PC2 (Extended Data Fig. 1). In vivo, proximal tubule flow velocities are ~300 µm/s 10. To quantify these forces, we used a flow chamber to measure cilia bending at defined plasma membrane shear stress values in cultured mIMCD cells isolated from Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mice (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 5). Flow velocities ranging from 3–400 µm/s (shear stress ~0.002–1 dyn/cm2) bent cilia (Fig. 3a, 3b) with half maximal bending at 70 µm/s (~0.11 dyn/cm2). A similar cilium-bending profile is observed in modeling the cilium as a uniform cylindrical cantilevered beam11,12.

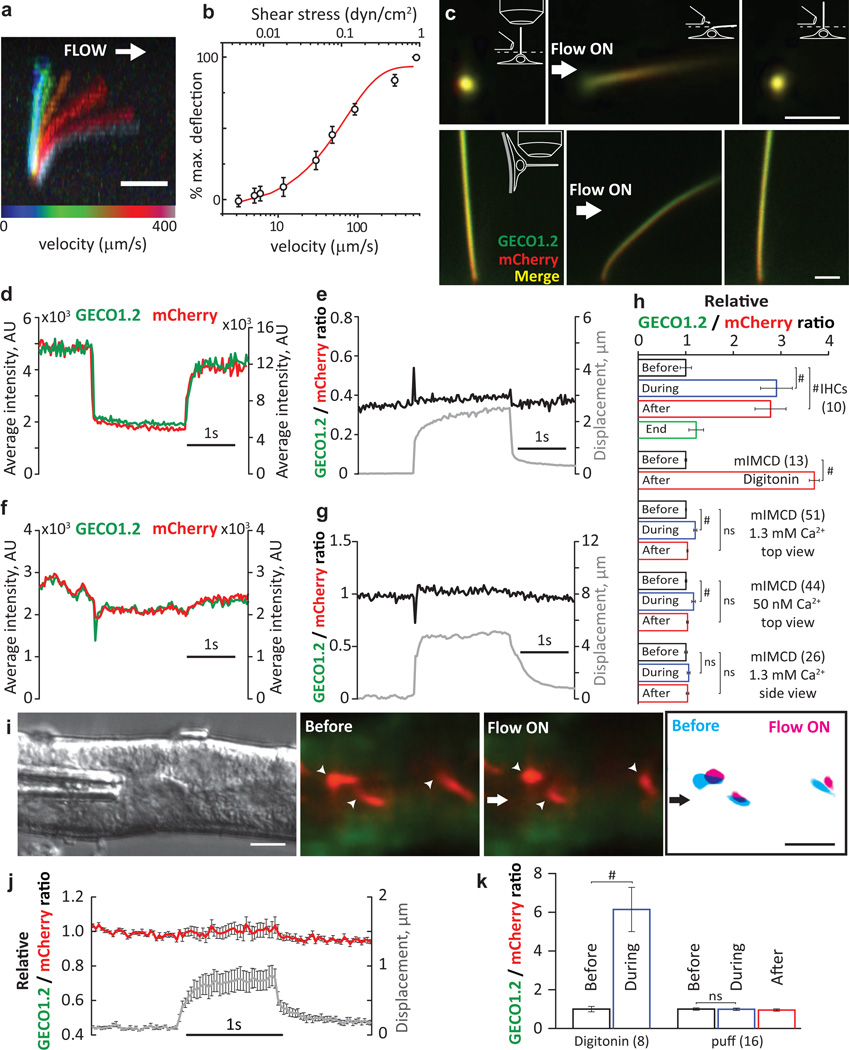

Figure 3. No change in [Ca2+]cilium during mechanical stimulation of kidney primary cilia.

a, mIMCD primary cilium at eight flow velocities (Extended Data Fig. 5). Scale bar, 5 µm; representative of 14 cilia (8 z-stacks, 12 focal planes each). b, Cilium deflection as a function of flow velocity and shear stress (n=14). c, Cultured primary mIMCD cells from P14-P21 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mice imaged from above (top panels; 87 videoes, 150 frames each: abbrev. 87v×150f) or the side (bottom, 32v×150 frames); pipette ~4–6 µm from cilium (Supplementary Video 2). Images: before, during, after 2s, ~250 µm/s flow velocity stimulus. A MATLAB tracking algorithm identified the ROI frame-by-frame and quantified GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence. Scale bars, 2 µm; d, Channel intensities from c top panel. When flow flattened cilia, average GECO1.2 and mCherry signals decreased due to changes in the light path. e, Ratioing GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence reduced artifact (Extended Data Fig. 6), revealing no Δ[Ca2+] during deflection. f, Side view fluorescence of c, bottom panel; GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence was relatively constant. g, Side-imaged F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratio unchanged by deflection. h, Normalized F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratios for positive controls (IHC stereocilia bundle deflection; data from Fig. 2c, and digitonin application); and for mIMCD primary cilia deflections in high and low [Ca2+], n in brackets. Small ratio differences are due to motion artifact (Supplemental Information, Extended Data Fig. 6). i, Perfusion of acutely dissected kidney thick ascending limb tubules (representative of 4 preparations) (Extended Data Fig. 5). Green: GECO1.2 and cytoplasmic autofluorescence; Red: mCherry. A train of increasing 1s pressure steps deflected intratubular cilia (arrowheads; Supplementary Video 5). Right panel, mCherry signal overlay from images before (cyan) and during (magenta) cilia deflection. Scale bars, 5 µm; 16v×200f (middle) j, No Δ[Ca2+] cilium for the smallest displacement in i. k, No Δ[Ca2+]cilium before, during and after deflection, data from j; (1.0 ± 0.06 before vs. 0.99 ± 0.06 during, n=16 cilia). Student’s t-test, # = p<0.001, ns = not significant. Error bars ± SEM.

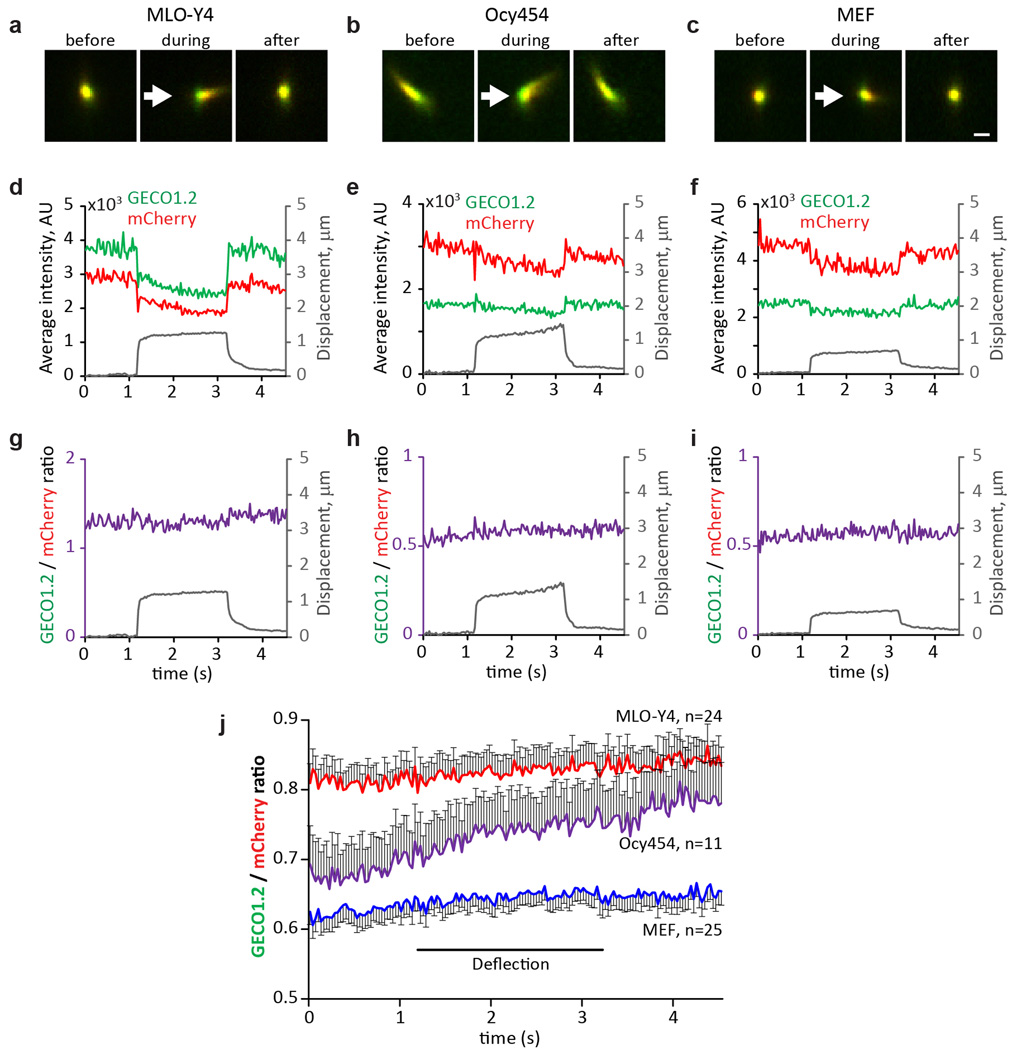

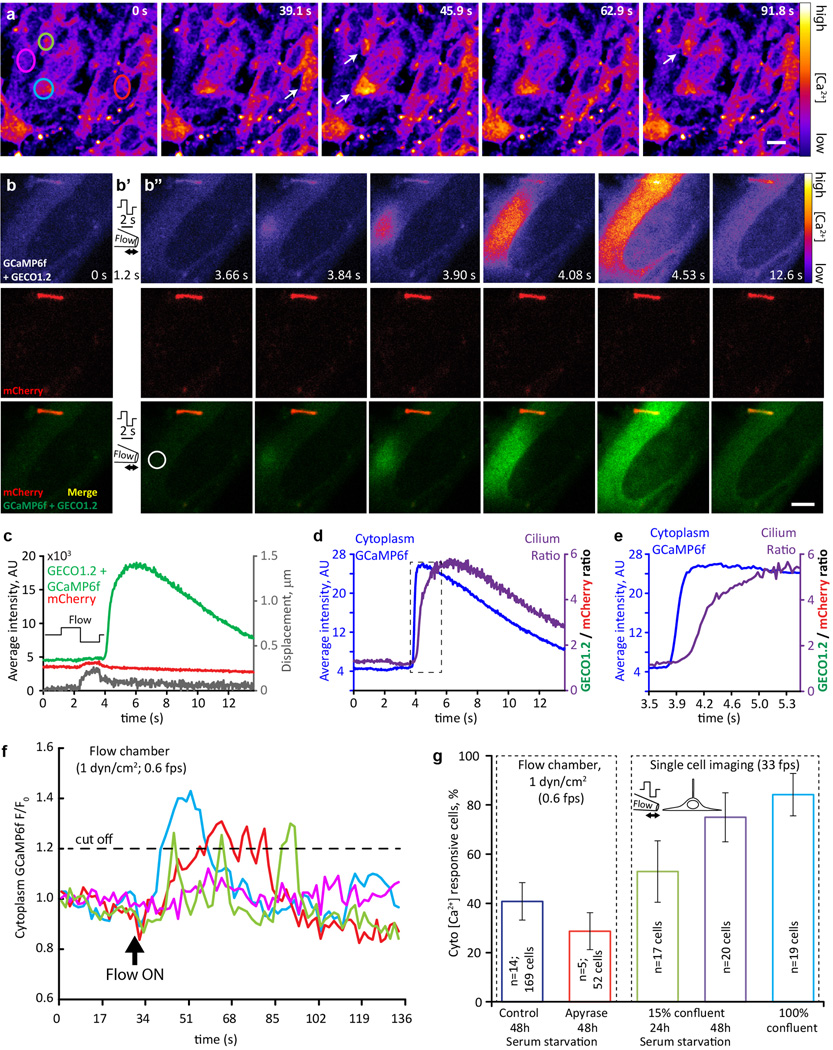

Primary cilia viewed from above were fully deflected by ~250 µm/s flow velocity (Supplementary Video 2; Fig. 3). Fluorescence intensities immediately dropped as flow flattened the cilium (Fig. 3c, d;). Ratioing F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry reduced this motion artifact (Fig. 3e; Extended Data Fig. 6). Imaging cilia from the side was most effective in reducing position/motion/path length artifacts; in this configuration, all parts of the primary cilium are in the same focal plane and never overlie the cell’s variable autofluorescence (Fig. 3c, bottom, Supplementary Video 2; Fig. 3f). Again, no change in [Ca2+]cilium was detected during deflection (Fig. 3g, h; digitonin control, Extended Data Fig. 6). Extending our study to other cell types, we found no CaRMS in osteocyte-like cells, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, or indeed, any primary cilia examined (Extended Data Fig. 7). Instead, we found that in all cases where [Ca2+]cilia increased, the Ca2+ rise was initiated at other sites in the cell and diffused from the cytoplasm into the cilium (Extended Data Fig. 8, 9, Supplementary Video 3). At low image acquisition rates (>200 ms/frame), this could easily be misinterpreted as cilia CaRMS3,9,13–15. At very high, nonphysiologic flow velocities and shear stresses (peak, 10 dyn/cm2 16), we observed that some cilia tips were ripped from the axoneme (Extended Data Fig. 9, Supplementary Video 4) and external 2 mM Ca2+ filled the breached cilium17.

In intact kidney tubules, primary cilia are deflected in a pulsatile pattern18. We microdissected kidney tubules from P21 mice and deflected primary cilia inside isolated tubules (Extended Data Fig. 5). A train of 1s stepped-amplitude flow stimuli in the lumen facilitated determination of the minimal flow deflecting cilia. Even flow sufficient to fully deflect cilia, however, did not change [Ca2+]cilium. Digitonin control increased Ca2+ ratios ~6 fold (Fig 3i–k, Supplementary Video 5).

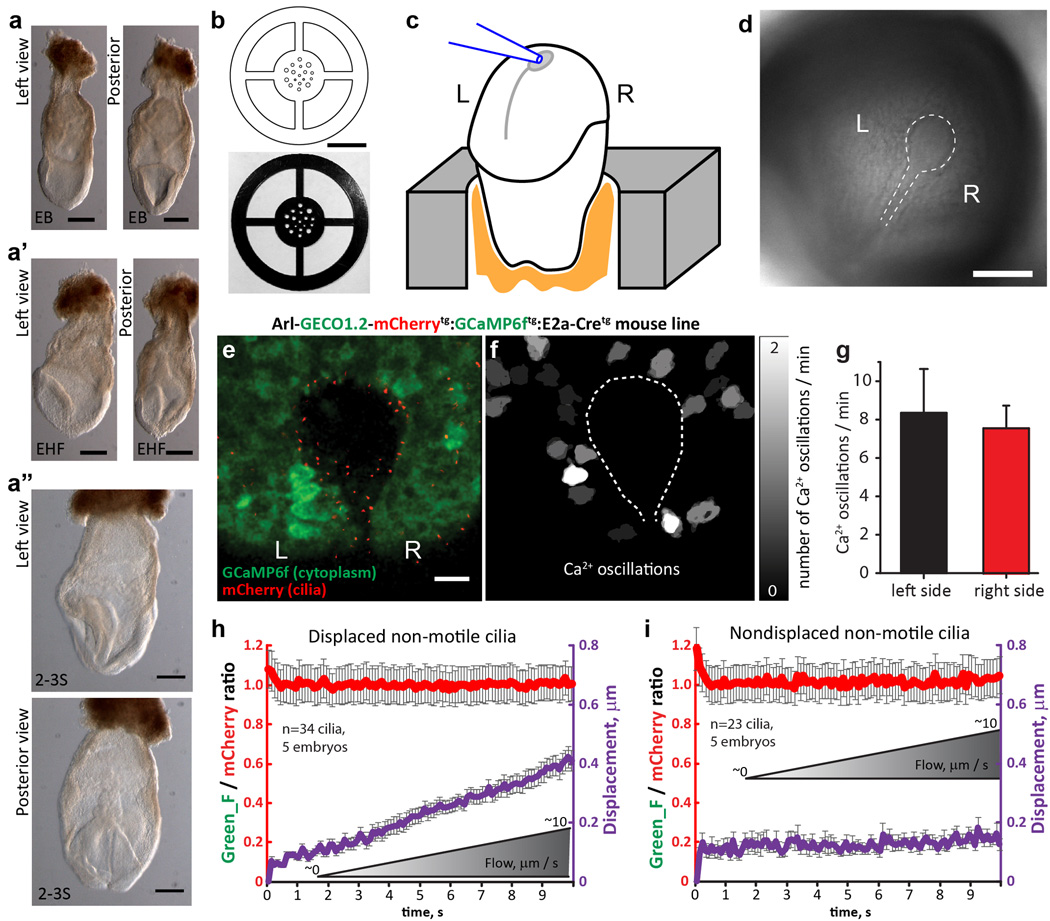

During embryonic development, structures that are initially symmetric along the body axis develop a left/right orientation. This orientation depends on cilia in the embryonic node, a depression at the distal tip of the embryo19. Specialized motile cilia (Supplementary Video 6) in the central node direct fluid leftward (viewed dorsally) at ~2–4 µm/s, which is believed to initiate asymmetric gene expression across the node20. Disruption of flow or mutations in primary cilia proteins result in left-right (l/r) patterning defects21 such as situs inversus, while imposed fluid flow to the right side reverts l/r patterning22,23. A prominent hypothesis is that left-side crown cell primary cilia are deflected by this flow, which mechanically activates ion channels in primary cilia and raises intracellular [Ca2+], leading to altered signaling and gene transcription in those cells and adjacent lateral plate mesoderm2,24. An alternative hypothesis is that the directed beating of nodal cilia creates a gradient of vesicles25 or a secreted morphogen26.

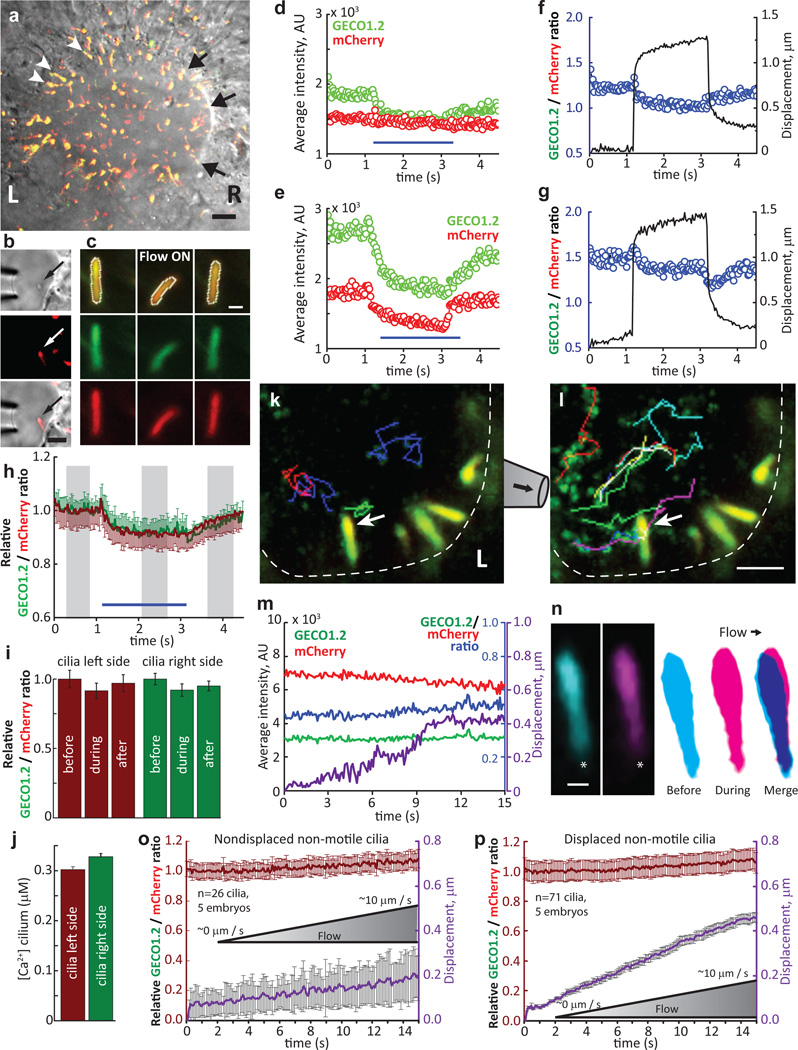

To test the mechanosensitive model, we measured [Ca2+] during deflection of left and right side nodal primary cilia (Fig 4a–b, k Extended Data Fig. 10, Supplementary Videos 7, 8). Cilia from developmental stages “early bud” (EB) to 2-somite were mechanically stimulated by applying flow using physiological levels (ramp from 0 µm/s to ~10 µm/s), or supraphysiological flow velocity of ~200 µm/s, similar to that previously shown to revert embryonic organ symmetry (Fig. 4b–c) 22. Deflection of left-or right-sided nodal cilia did not change [Ca2+]cilium (Fig. 4d–i). These results demonstrate that primary cilia of the embryonic node are not CaRMS from physiological flow velocities to those 50–100 times greater. Notably, physiologically-relevant flow velocities (<~10 µm/s) barely deflected nodal crown cilia (458 ± 22 nm, Fig. 4k–p, Extended Data Fig. 10, Supplementary Video 9) as predicted (Fig. 3a, b). Resting [Ca2+] was ~300 nM in both left- and right-side cilia (Fig. 4j; see ref23).

Figure 4. No change in [Ca2+]cilium in primary cilia of the embryonic node.

aArl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg embryonic node, early headfold stage (EHF); l=left, r=right. Nonmotile cilia; l, white arrowheads; r, black arrows. Scale bar, 20 µm. (n=4 embryos) b, Crown-cell cilia deflected by 2s/~200 µm/s flow velocity. 2v×500 frames. Scale bar, 5 µm. c, Cilia from the l outer perimeter before (l), during (mid) and after (r) ~200 µm/s flow velocity. Top row: merged GECO1.2 and mCherry signals. White outline, ROI. 32v×150f. d, e, GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence of a l (d) and r (e) nodal cilium; ~200 µm/s. f, g, Ratiometric changes on l (f) and r (g) sides; ~200 µm/s cilia deflection (black trace; same cilia as d, e). h, Average relative ratio changes for cilia on the l (burgundy, n=29) and r (green, n=15) sides of the node. i, Relative ratio changes; grey boxes in h, time blocks quantified. j, Resting [Ca2+] in l- and r-side nonmotile primary cilia. [Ca2+] calculated as in Extended Data Fig. 2, Methods). (l cilia: 1.0, n=67, 4 nodes; r cilia: 1.1, n=72, 5 nodes); resting [Ca2+] l: 302±6 nM; r: 320±7 nM). k–l, Cilia on the I outer perimeter (dashed white line) with no net flow, k, or ~10 µm/s flow velocity, l, measured near the cilium (arrow). Coloured lines, tracks of beads; Supplementary Video 9). Scale bar, 5 µm; 42m×150f. m, Traces of cilium in k–l (arrow). Displacement of cilium during 0 to 10 µm/s ramp in purple. n, Cilium in k (arrow) at ~0 µm/s (l, frame average), ~10 µm/s (middle, frame average, end of deflection), and superposition (r, note <1 µm deflection). *, ciliary base. Scale bar, 500 nm; 42m×150f. o, p, Ratio changes of I crown-cell cilia from LB to 3-somite stage during flow from ~0 to ~10 µm/s velocities. o, Ratio change for nondisplaced cilia (n=26 cilia, 5 embryos), p, Ratio change for displaced cilia (n=71 cilia, 5 embryos; avg. centroid displacement, 458 ± 22 nm). All error bars ± SEM.

In summary, mechanical forces do not evoke Ca2+ signaling within up to 10 s of stimulation in the cilia of kidney tubules, the embryonic node, several cell lines used as models of cilia function, or kinocilia. Since mechanosensitive channels and putative mechanically-gated G-protein-coupled receptors respond in the 10 µs-100 ms range27,28, we suspect the reported increases in [Ca2+]cilium after ~10–20s stimulation3,15 originate from the cell body. Indeed, imaging up to 100 Hz revealed that nonciliary origins were always the initial site of Δ[Ca2+] (Extended Data Fig. 8, 9 and Supplementary Video 3) and the Ca2+ wave initiated in the cytoplasm propagated into the primary cilium. To account for previous observations, we speculate that the two primary sources of error were: (1) insufficient time resolution - Ca2+ originating from the cytoplasm can diffuse into the cilium in <200 ms and be mistaken as originating from within the cilium; and (2) motion and light path-dependent artifacts. Finally, we do not imply that there are no mechanosensitive elements in primary cilia in physiologically relevant ranges, since motor, cytoskeletal, and other proteins are affected by changes in geometry and force without changes in ciliary [Ca2+]29. An important implication of these findings is that situs inversus and polycystic kidney disease caused by the loss of polycystins23,30 are not due to loss of mechanically-induced cilia-initiated calcium signaling. These data should motivate investigators to focus on other potential mechanisms for regulation of ciliary ion channels, and to determine whether calcium propagation into the cilium from the cytoplasm affects ciliary function.

Online Methods

Molecular biology, transgenic animals

The ScaI/HindIII linearized hArl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 pCAG vector (chicken actin promoter) was gel-purified and injected into the pronucleus of C57BL6/6J oocytes at the transgenic animal core facility at Boston Children’s Hospital (Boston, MA). The integration site for the Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 transgene was determined by genomic walking (Bio S&T). The genotype of transgenic animals was determined by PCR: primers 372-up: ACATGGCCTTTCCTGCTCTC, 372-down: TTCAACATTTCCGTGTCGCC and 944-down: GACATCTGTGGGAGGAGTGG. PCR product for the wt genomic sequence: ~800 bp; transgene PCR product ~400 bp. All animal procedures of this study were approved by the IACUCs of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Animals were maintained according to ARCH standards at Boston Children’s Hospital and euthanized using CO2.

Isolation of primary mouse inner medullary collecting duct epithelium cells (mIMCD)

Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg: mIMCD cells were isolated as described31. Briefly, 10 kidneys isolated from P14-P21 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg mice were cut longitudinally with fine scissors and the outer and inner medulla removed. The tissue was cut into small pieces with a razor blade and digested in collagenase (2 mg/ml) and hyaluronidase (1 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C in L-15 medium (Life Technologies). After trituration of the homogenate, cells were washed x2 in PBS and plated on laminin-coated dishes (Life Technologies). Cells were grown in DMEM (adjusted to 600 mOsm with urea and NaCl), containing 200 µM dibutyryl-cAMP (db-cAMP), unless stated otherwise. After 2 days, cells were split on laminin-coated coverslips (NeuVitro) and imaged after culturing for an additional 1–2 days to allow confluent cell growth. For side-view imaging cells were grown on 24 mm transwell inserts (corning) until they reached confluency. The membrane was excised with a scalpel and folded before imaging. Where indicated mIMCD cells where serum starved in DMEM containing 0.2% BSA for 24 h or 48 h. Imaging solutions: L-15 medium (1.3 mM Ca2+) or HEPES-containing solution buffered to 50 nM [Ca2+], see Calibration of Sensor for buffer composition.

Microdissection of hArl13b;-mCherry-GECO1.2tg kidney tubules

Microdissection was carried out as described previously32 with modifications. In brief, 1-mm thick transverse slices of P14-P21 kidneys were incubated with collagenase (1 mg/ml) and hyaluronidase (1 mg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C in L-15 medium (Life Technologies), or gently dissected without prior treatment. The cortex was removed with fine forceps and bundles of tubules were isolated at the transition of inner (white) and outer (red) medulla (Extended Data Fig. 5 c). Thick-walled individual tubules with luminal fluorescent cilia were microdissected and mounted on glass or plastic coverslips coated with Cell-Tak (Corning). Under 4x magnification (upright Nikon NiE), a micromanipulator-mounted 20° micro-knife (Minitool) was used to cut individual tubules from the bundles. A second micromanipulator held a long-tapered micropipette (bent ~20° to ensure the tip of the pipette was parallel to the surface of the coverslip, Extended Data Fig. 5). Under higher magnification (100x/1.1 N.A. or 60x/1.0 N.A. water dipping lenses) the micropipette was gently inserted into the tubule lumen and the pressure stimulus applied. Regions of the tubule with no direct micropipette contact were used for Ca2+ imaging. In some experiments a third micromanipulator was used to deliver digitonin (20 µM) to the tubules (direct injection into the tubule lumen or external application). Cilia from kidney tubule perfusion experiments were collected from 3 independent microdissections.

Isolation of hArl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg and hArl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg:GCaMP6ftg:E2aCretg embryos

GCaMP6f (B6;129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm95.1(CAG-GCaMP6f)Hze/J) and E2a-Cre (Tg(EIIa-cre)C5379Lmgd) transgenic animals were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Embryo isolation was performed as described previously33. Timed pregnancies resulting from mating wild type C57BL6/6J, Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/− or Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg females with Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg or GCaMP6ftg/tg:E2a-Cretg/tg males yielded embryos that were then selected for the appropriate developmental stages34. Embryos expressing motile cilia in the embryonic node at stages critical for asymmetric gene expression 35 (starting at developmental stages “early allantoic bud” (EB) up to 2-somite stage) were used for experiments. Embryos were mounted with the embryonic node facing up in a custom-designed embryo mounting plate (Extended Data Fig. 10 b–d). Laser cut holes (diameters 0.5–1.2 mm) in 0.8 mm Delrin ensured a good fit of the embryo into the holding well (Extended Fig. 10 b–c). All embryonic node imaging was performed in DMEM/F12 with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen).

Similar mating strategy was used to obtain Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg:GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg E14 embryos. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were isolated from E14 embryos as described previously17. Where indicated, MEF cells were serum starved in DMEM containing 0.2% BSA for up to 48 h. To visualize cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations, Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg: GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg embryos from LB to LHF stage were used. In brief, embryos were mounted in the upright position as described above and imaged for 4–6 min at a frame rate of 0.5 Hz on an upright FV1000 confocal system (Olympus, 60x/1.1 N.A. water dipping lens) at either 36°C or 22°C (RT). Cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations were quantified using ImageJ as described previously33 with slight modifications: in brief, fluorescence of all frames was averaged and individual frames were divided by average intensity to generate ΔF/F. Images were thresholded to exclude cells with ΔF/F less than 30%. Furthermore, only regions with area >90 pixels2 and circularities greater than 0.6 were used to define cells with cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations. All Ca2+ oscillations within 0.01 mm2 surrounding the embryonic node were analyzed for occurrence on the left vs. the right side of the node.

Reagents

Mouse anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich; T7451); CF 405M Phalloidin to stain filamentous actin (Biotium; 00034); goat anti-PC2 (Santa Cruz; G-20 sc-10376), rat anti-mCherry (Life Technologies; M11240), chicken anti-EGFP (Aves labs; GFP-1020).

Immunocytochemistry, confocal microscopy

Cells or embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked by 10% donkey serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were labeled with the indicated antibody followed by secondary donkey anti-rabbit, anti-goat, or anti-mouse fluorescently-labeled IgG (Life Technologies) and Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies). Confocal images were obtained using an inverted Olympus FV1000 (60× 1.2 N.A. water immersion objective lens) and images processed using ImageJ (NIH).

Immunohistochemistry

Fixed (4% PFA) 15 µm frozen tissue sections were permeabilized with 0.5% TX100 / PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 min and blocked with PBS containing 5% goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% fish gelatin, 0.1% TX-100 and 0.05% Tween20. For primary antibodies raised in mice, endogenous mouse IgGs were blocked by incubating sections with the unconjugated Fab fragment goat anti-mouse IgG for 1 h at RT. For goat primary antibodies donkey serum and donkey secondary antibodies were used. Sections were washed twice in PBS-T, incubated with primary antibodies in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed x2 in PBS-T and goat anti-rabbit/anti-mouse fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies applied at RT for 1 h with Hoechst 33342 (nuclear) dye. Sections were washed x2 in PBS-T, mounted in Prolong Gold Antifade (Life Technologies) and imaged (inverted Olympus FV1000; 60x, 1.2 N.A. water immersion objective). Images were further processed with ImageJ (NIH).

Ca2+-imaging in stereocilia and primary cilia

Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2-expressing cilia were observed under an upright Nikon NiE microscope (100x, 1.1NA, 2.5WD) equipped with an Opterra swept-field confocal imaging system (Bruker Nano Technologies) and a Photometrics Evolve 128 liquid-cooled EMCCD camera (128 × 128 pixels, 120 nm effective pixel size). This system enables fast imaging of up to 500–1000 fps in low-light conditions. In most cases, tissue was illuminated sequentially by 488 nm (GECO1.2) and 561 nm (mCherry) laser light, and imaged using the full CCD chip (15 ms exposure/channel; 33 fps). To increase light delivery to the camera and avoid excessive photobleaching, swept-field confocal imaging was performed in slit mode (35 µm).

Measurements of cilia bending and flow velocities

mIMCD and MEF cells isolated from hArl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg mice were seeded in an IBIDI µ-Slide VI 0.4 flow chamber coated with laminin (see IBIDI Application Note 11; for this chamber, apical membrane shear stress is: τ = η131.6 Φ: where η is dynamical viscosity (0.01 dyn s cm−2) and Φ is flow rate in ml/min. A syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) delivered steady flow via 10 ml syringes containing L-15 medium. Z-stacks of primary cilia were recorded on an inverted Olympus FV1000 (60x, 1.2 N.A. water immersion objective). The bend angle was measured between ciliary base and tip18. Fluid velocities were measured by imaging the flow of the solution supplemented with 300 nm green fluorescent beads (Sicastar greenF, Micromod) at the focal plane corresponding to ciliary tips at rest. Images were acquired as line scans (2 ms/line) or in continuous scanning mode (64 or 128 ms/frame) and particles tracked using an ImageJ plugin.

Calibration of the ratiometric Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 sensor

Calibration was performed using an inverted Olympus FV1000 (60x, 1.2 N.A. water immersion objective) as described previously17. In brief, standard solutions of [Ca2+] (ranging from 50 nm to 50 µM) were prepared by adjusting the ratio of EGTA and CaCl2 (MaxChelator) in 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES. After isolation, mIMCD cells were plated onto 12 mm laminin-coated glass coverslips (Neuvitro) and cultured for 3–4 days to allow cilia formation. For controls, digitonin membrane permeabilisation (3 min) was followed by image acquisition in multiple fields of view. Ratios were obtained by dividing the GECO1.2 average fluorescence intensity (per ROI, corresponding to a single cilium) by the average mCherry fluorescence intensity. The average ratios were plotted as a function of free [Ca2+] fitted to a sigmoid curve: y = A2 + (A1-A2)/{1 + exp[(x-x0)/dx]}: A1 = 0.15 ± 0.03, A2 = 1.58 ± 0.06, x0 = 442 ± 25, dx= 114 ± 20 with x0 = kD. The kD of bacterially expressed/purified GECO1.2 was 1.1 µM36, about twice the kD measured for our GECO1.2 fusion construct in mammalian cells in situ. [Ca2+] in embryonic node primary cilia was estimated from an Rmin- and Rmax-adjusted calibration curve, where both values were calculated from images collected on swept-field confocal imaging system. Late Bud (LB) to late headfold (LHF) embryos were permeabilised with 20 µM digitonin (5 min) in either 50 nM or 5 µM [Ca2+]. Resting values for nodal primary cilia were measured in DMEM/F12 +10% FCS using the same imaging settings used to calculate Rmin and Rmax. Ratios were converted to [Ca2+] using the adjusted Ca2+ calibration curve.

Primary cilia and stereocilia deflections

Primary cilia and stereocilia bundle deflections were performed using a custom-made fluid-jet system. Briefly, the micropipette pressure at the back of the pipette could be rapidly changed to a desired value by supplying vacuum and/or pressurized air via feedback-controlled solenoid valves (5–10 ms rise time for the pressure step stimulus). The micropipette was filled with bath solution and the pressure at the mouth of the pipette carefully adjusted prior to approaching to the cilium, ensuring that there was no flow applied to the cilium before the onset of the stimulus. Depending on the experimental design, digitonin was applied to the cells either using the fluid-jet pipette, or via an additional pipette positioned near the cilium and connected to an IM-9C microinjector (Narishige).

For kinocilium deflection experiments, organ of Corti explants were acutely dissected and mounted on a coverslip coated with CellTak, or immobilized with tungsten minutien pins (FST). All hair cell imaging experiments were performed at RT in L-15 cell culture medium (Invitrogen), containing in mM: NaCl (138), KCl (5.3), CaCl2 (1.3), MgCl2 (1.0), Na2HPO4 (1.0), KH2PO4 (0.44), MgSO4 (0.81). For stereocilia bundle Ca2+ imaging experiments, organ of Corti explants were dissected at P5 in L-15 medium and placed in culture in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% FBS and 10 mg/l ampicillin at 37°C (10% CO2). Explants were cultured for 3 days to increase the number of cells with sufficient sensor in stereocilia bundles.

All images were analyzed using a custom-made MATLAB tracking algorithm (described below), ImageJ (NIH), and Origin 8 (OriginLab).

Osteocyte-like cell lines, MLO-Y4 and Ocy45437 were tested for authenticity and mycoplasma contamination in the laboratories who supplied them (see Acknowledgements). Both cell types were transfected with a plasmid encoding hArl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 using electroporation (LONZA, solution V, program T-20), as described previously38. Cells were seeded on coverslips after transfection and cultured at 37°C. Cells were used after a primary cilium was visible.

Embryonic node cilia were deflected with either a fast fluid-jet stimulus (described above), or with a ramp of slow, physiological level flow, delivering up to ~10 µm/s velocities: fluid flowed from a gravity-fed open-ended syringe to the micropipette. Flow rates were calibrated using 100 nm fluorescent beads (Sicastar-greenF, Micromod) and adjusted by gently lifting the syringe up 5–10 mm using a coarse micromanipulator. Perfusion fluid contained 100 nm fluorescent beads at 10 µg/ml, was applied directly to the node via micropipette (pipette opening 4–6 µm in diameter) that was 4–6 µm away from the imaging area. Flow rates were adjusted manually as described above such that there was no net flow at the beginning of the experiment and ~10–12 µm/s velocity at the end of the 15 s imaging experiment. Bead velocities and tracks were quantified and visualized using the “manual tracking” plugin in ImageJ.

Pipette flow calibration

Pipette flow was calibrated using 300 nm fluorescent beads (Sicastar-greenF, Micromod) re-suspended at 0.5 mg/ml in DMEM/F12 10% FCS and loaded into micropipettes following sonication. A pressure stimulus was applied to the back of the pipette and steady flow imaged at 1000 fps to ensure accurate frame-by-frame reading for each bead position while exiting the pipette and during its travel across the imaging area (~15 µm). The 1-ms time resolution of the calibration experiment was sufficient to resolve and calibrate the range of velocities used.

Scanning electron microscopy

Cultured mIMCD cells were fixed for 1 h at RT with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2, and stored in distilled water. Organ of Corti explants were fixed following Ca2+ imaging experiments, or the entire cochlea was fixed and later microdissected in distilled water and prepared for SEM as previously described39. Briefly, specimens were dehydrated in ethanol, critical point dried from liquid CO2, mounted on a carbon tape, sputter-coated with 5 nm platinum, and imaged on a Hitachi S-4800 field emission SEM.

Data analysis

All images were analyzed using a custom-made MATLAB tracking algorithm (described below), ImageJ (NIH), and Origin 8 (OriginLab); in stereocilia we observed a 2.9 ± 1.05 [M ± StDev] fold change (effect size d=2.76) in GECO1.2/mCherry ratio after activation of a Ca2+ - conducting mechanosensor. Assuming a one-sided, paired t test conducted at the 0.05 level of significance, a minimum of 12 cells would be required to detect an effect size of d=1 in mechanosensitive [Ca2+] increase post-stimulation with 95% power.

Image analysis

Customized image analyses were developed using MATLAB to automatically process the large volume of ratiometric time-lapse data in order to improve quantitation and objectivity. The analysis is divided into three steps: channel alignment, object detection, and object tracking over time, with subsequent ratio calculations.

Channel alignment

Two factors contribute to misalignment of two channels during image acquisition: chromatic aberration from the optics and time delay due to sequential acquisition. For chromatic aberration, the two channels from each frame of a given time-lapse image were aligned using a translational transformation. A global translational transformation, derived from the individual frame transformations, was applied to all frames.

Object detection

Frame-by-frame superimposed images of both channels were created. When cilia motion was faster than acquisition time, channels were significantly misaligned. To create a combination image, two channels were added and smoothed using a Gaussian filter. Local image background was subtracted from the combination image, and Otsu thresholding used to detect objects. Small objects (less than 3 pixels) were filtered as noise.

Object tracking with ratio calculations

Different cilia in the same image vary with relative orientation. During flow application, many cilia undergo large deflections and even cross one another, further complicating the tracking of individual cilia. A tracking algorithm based on object overlap was implemented. It included features such as splitting of crossed cilia, linking cilia with no spatial overlap, and closing gaps over a given number of time frames. Once an individual cilium was tracked, the analysis code measured the signal of the cilium from both channels, calculated the ratio, and plotted it against time or spatial displacement.

Code availability

The algorithms were developed in MATLAB in open-source, and are available upon request.

Extended Data

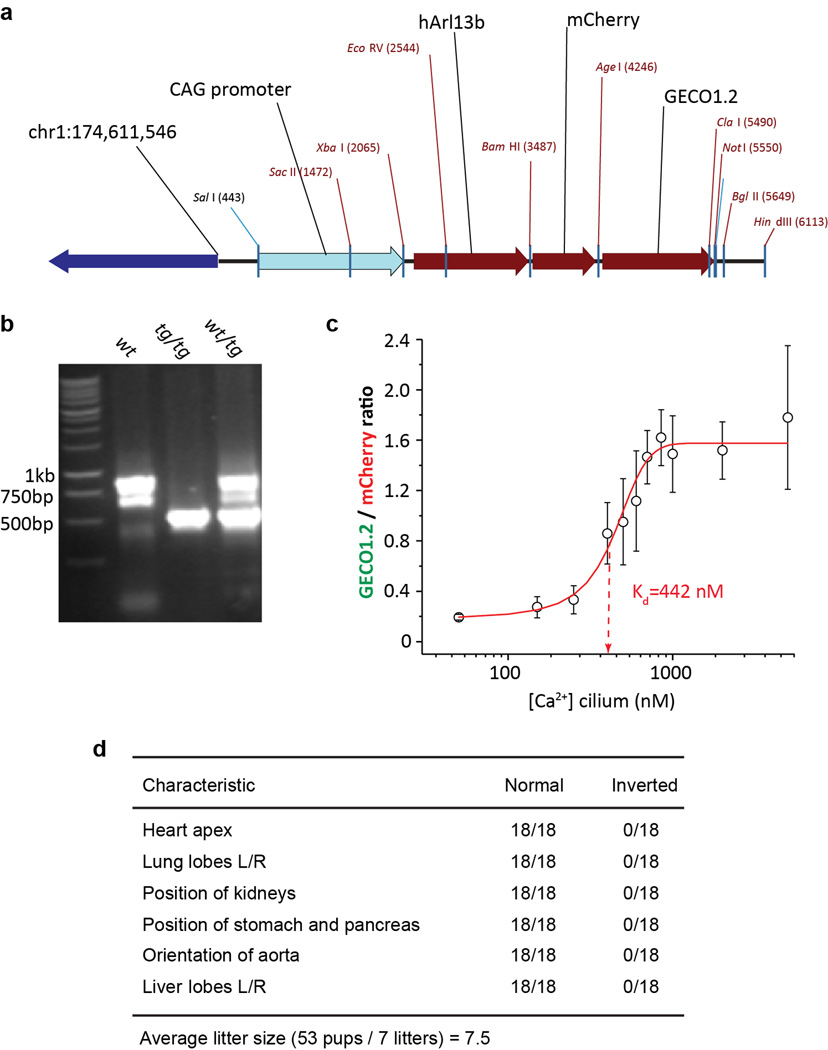

Extended Data Figure 1. Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 identifies primary cilia.

Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 contains an improved genetically encoded calcium indicator36 (GECI) with an apparent kD of 450 nM (Extended Data Fig. 2), well suited to work within the reported range of ciliary Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]cilium)40. The genomic integration site of the transgene is within a non-coding region of chromosome 1 (Extended Data Fig. 2) and transgenic animals maintained as homozygotes (Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg) are viable, have average litter sizes, and do not show phenotypes consistent with cilia defects (e.g., situs inversus, organ malformation; Extended Data Fig. 2).

a, Frozen tissue section of P21 mouse kidney. GECO1.2 and mCherry are preferentially localized to cilia, identified by the cilia-specific marker, anti-acetylated tubulin antibody. b, c, Primary mIMCD cells isolated from kidneys of P14-P21 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 transgenic mice. Ciliary localization (arrow) of anti-polycystin 2 antibody in c. Scale bars, 10 µm. d, Two OHC hair bundles marked with the actin-binding peptide, phalloidin. One of the stereocilia bundles expresses Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2. Kinocilia on both OHCs marked with an antibody to acetylated tubulin, express Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2. Scale bar, 5 µm. e, Scanning electron micrograph of a primary mIMCD cell. Left: Red dashed line outlines a single mIMCD cell; white circle indicates the primary cilium: Scale bar, 10 µm. Right, magnified image. No defects in cilia formation were evident following 3–4 days in culture. Scale bar, 500 nm. All images are representative of >10 images taken of biological triplicates.

Extended Data Figure 2. Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 transgenic mouse.

a, Transgene orientation and integration site. The transgene was integrated into the noncoding region of Chromosome 1 (pos. 174,611,500). b, The genotype of transgenic animals was determined by PCR using primers 372-up: ACATGGCCTTTCCTGCTCTC, 372-down: TTCAACATTTCCGTGTCGCC and 944-down: GACATCTGTGGGAGGAGTGG. The PCR product for wt genomic sequence was ~800 bp; the transgene PCR product was ~400 bp. c, mIMCD cells isolated from Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg mice were imaged after permeabilisation with 15 µM digitonin in varying extracellular [Ca2+]. Average ratios (n = 12 cilia per each data point) are plotted vs. free [Ca2+]. Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 calibration fitted by a Boltzmann curve (R2 = 0.98; kD = 442 nM). d, Phenotype of Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mice. Mouse organ morphology/orientation appeared normal (situs inversus was not observed) and breeding animals had normal litter sizes (6–8 for C57Bl/641). All error bars ± SEM.

Extended Data Figure 3. Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mouse organ of Corti hair cells develop normal stereocilia bundles.

Hair bundles from Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg mice during development. a–d, Cochlear hair cells acutely dissected at age E18 appear normal. a, IHC, with kinocilium not attached to stereocilia. b–c, OHC stereocilia bundles with some kinocilia attached to the bundles. d, IHC bundle with kinocilium attached at tip. e–i, Cultured organ of Corti explant dissected at P1 + 1 day in vitro. e, OHC with normal shape and stereocilia staircase structure. f, OHC stereocilia bundle with kinocilium. g, IHC with normal shape and stereocilia staircase structure; tip links and other links present. h, Pair of stereocilia (dashed box in f) at higher magnification. i, IHC with kinocilium attached at tip. Scale bars, 1 µm (except g, 100 nm). All images are representative of >3 images.

Extended Data Figure 4. GECO1.2 koff for Ca2+ dissociation from GECO1.2, measured in cells.

a, b, Fig. 1g at higher time resolution. F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratio (open circles) relative to bundle motion (black line) at the initial deflection, a, and after return to the resting position, b. Bundle deflection preceded the F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratio increase by two frames (~60 ms). At the termination of the flow stimulus and return to the resting position, the ratio remained elevated due to the slow decay (τ ~ 0.6 s) of the Ca2+ from GECO1.2. c, Rapid Ca2+ uncaging was used to measure the Ca2+ decay rates for GECO1.2 (not bound to the membrane), Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 (bound to the membrane), and the Fluo-4 control with its established time constant of decay. HEK293 cells were transfected with GECO1.2 or Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 constructs and loaded with caged Ca2+ (NP-EGTA), or loaded with a combination of Fluo4-AM and NP-EGTA. Caged Ca2+ was released by a local 100–200 ms pulse of UV laser illumination (white box); images were acquired in line scan mode (2 ms/horizontal line). Representative of >16 images. d, Representative fitted fluorescence intensity decays of Fluo-4 in HEK293 cells (black), GECO1.2 (red), and Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 (blue), compared to GECO1.2 from Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg IHCs following deflection (green). e, Table summarizing molecular properties of genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECI’s) used in current and previous reports describing ciliary Ca2+ signaling14–17,36,42–45. f, Average decay rates, τ, for indicators in c, d. Fluo-4: τ = 154 ± 36 ms (n=16); GECO1.2 in HEK293 cells: τ = 203 ± 50 ms (n=19); Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 in HEK293 cells: τ = 358 ± 55 ms (n=16); Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 in IHC stereocilia: τ = 601 ± 70 ms (n=10). Averages ± S.D.

Extended Data Figure 5. Kidney tubule dissection and flow velocity calibration.

a, Calibration of the fluid velocity exiting the stimulus pipette vs. distance from the mouth of the pipette (3-µm pipette, 6.4 mm Hg pressure step). The pipette was positioned ~4–6 µm from the cilium, delivering a flow velocity of 250–300 µm/s (n=5). b, Velocity measured at the tip of the cilium and calculated shear stress at the plasma membrane (n=6). c, Microdissection of kidney tubules. c1: Coronal section of P15 kidney; white box indicates the microdissected area. c2: Area from c1 following microdissection. c3: Small bundle of tubules; individual tubules gently separated from the bundle (arrow). c4: Tubules with thick walls and fluorescent cilia (asterisk) used for experiments. Scale bar, 5 µm. Images representative of >6 preparations. d, Maximum intensity z-projection of mIMCD primary cilia deflected in the flow chamber using defined fluid velocities. Scale bar, 3 µm; representative of 14 cilia each with 7 z-stacks containing 12 frames. e, Relative ratio changes in primary mIMCD primary cilia during deflection, 3 experimental conditions. Black and blue lines represent the averaged normalized ratio changes for top views of cilia deflection in 1.3 mM and 50 nM [Ca2+], respectively. The increase in ratio upon cilia deflection is comparable between high and low external [Ca2+], suggesting that the ratio change did not result from Ca2+ entry (Fig. 3h for p values). In addition, the return to baseline with cilium movement was much faster than the Ca2+ indicator response time, providing further evidence that it is a motion artifact. Such fast responses were not observed in the bona fide Ca2+ entry into IHC stereocilia (Fig. 2a, Extended Data 4b, d). Purple line represents the average normalized ratio changes for side-imaged cilia deflections in the presence of 1.3 mM [Ca2+]. Ratio changes were negligible in side views, as the motion artifact (light path length change upon motion) is small. The positive slope seen in top views results from differential dye bleach, faster for mCherry than GECO1.2. Bleaching has a much more pronounced effect in top views, probably from the change in geometry, contribution from underlying autofluorescence, and relative light exposure upon bending. f, Micropipette used for cilia deflection inside the kidney tubules. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. g, Insertion of micropipette into the tubule. Scale bar, 100 µm. All error bars ± SEM.

Extended Data Figure 6. Deflection of primary cilia in the presence of 50 nM [Ca2+] reveals focal plane-dependent artifact present in ‘top view’ imaging conditions. Saturation controls for sensor.

a–c, An mIMCD cell cilium was repeatedly deflected in a low (50 nM) [Ca2+] solution. The same flow stimulus (same pipette) was applied to the cilium while imaging in different focal planes. Top panels: experimental arrangement and fluorescence images of the cilium; red dashed lines indicate the focal plane for each set of images. Middle panels (a’–c’): average fluorescence intensity change for GECO1.2 (green) and mCherry (red) during deflection (black). Lower panels (a”–c”): ratio change (blue) during deflection (black). a, Primary cilium near its attachment to the cell. b, At a slightly higher focal plane, deflection enlarges the cross section of the cilium. c, A focal plane ~1 µm above the cell surface. Different segments of the same cilium were imaged upon deflection. Note that the artifact increases with larger cross section changes. Thus, top view imaging of cilia is fraught with two interrelated artifacts: 1) at high z-resolution (0.8 µm), the section of the cilia being imaged changes upon deflection, thus conflating fluorescence changes from different regions of the cilium; 2) at lower z-resolution, the path length, fluorescent indicator volume, and optical properties of the cilium above and below the image plane all change upon deflection and thus contribute to the apparent [Ca2+] reporter changes. d–e, Digitonin permeabilization indicates that the Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 sensor is not saturated in measurements of primary cilia and kinocilia. Scale bars, 2 µm. d, Top: mIMCD cell cilium deflected by fluid flow containing 10 µM digitonin. Bottom left: mCherry fluorescence (red) decreased due to cilia motion (black). GECO1.2 fluorescence (green) rose ~1 s later, as permeabilisation initiated Ca2+ influx. Right: F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratio increased ~4.2-fold upon permeabilisation. Representative of 13 videos × 400 frames. e, Kinocilia of E15 cochlear hair cells. Digitonin (10 µM) increased the kinocilium’s normalized F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry ratio by 4.6-fold. Representative of 6 videos × 400 frames. Similar results were obtained in P3 hair cell kinocilia (data not shown).

Extended Data Figure 7. No change in [Ca2+]cilium during mechanical stimulation of primary cilia in MLO-Y4 and Ocy454 osteocyte-like cells, and primary MEF cells.

a–c, Cultured MLO-Y4 (a, representative of 24 videos × 150 frames), Ocy454 (b, representative of 11 videos × 150 frames) and MEF cells isolated from E14 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg:GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg mice (c, representative of 25 videos × 150 frames) were imaged from above; stimulus pipette was placed ~4–6 µm away from the cilium. Images: cilium before, during and after deflection by a 2 s, ~250 µm/s flow stimulus. The ROI was identified frame-by-frame by a MATLAB tracking algorithm and GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence quantified. Scale bar, 1 µm. d–f, Quantification of the channel intensities from the cilia in a–c. Average fluorescence intensity for both GECO1.2 and mCherry signals decreased as the cilia flattened and the light path length via the cilium volume changed. Cilium ROI displacement is superimposed in grey. g–i, Ratioing GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence compensated for the path-length artifact (see also Extended Data Fig. 6), revealing no Δ[Ca2+] during deflection. Cilium ROI displacement is superimposed in grey. j, Average ratio changes (F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry) for MLO-Y4 (red, n=24), Ocy454 (purple, n=11) and MEF (blue, n=25) primary cilia. The small continuous positive slope during the entire course of the experiment results from differential dye bleaching (mCherry > GECO1.2). All error bars ± SEM.

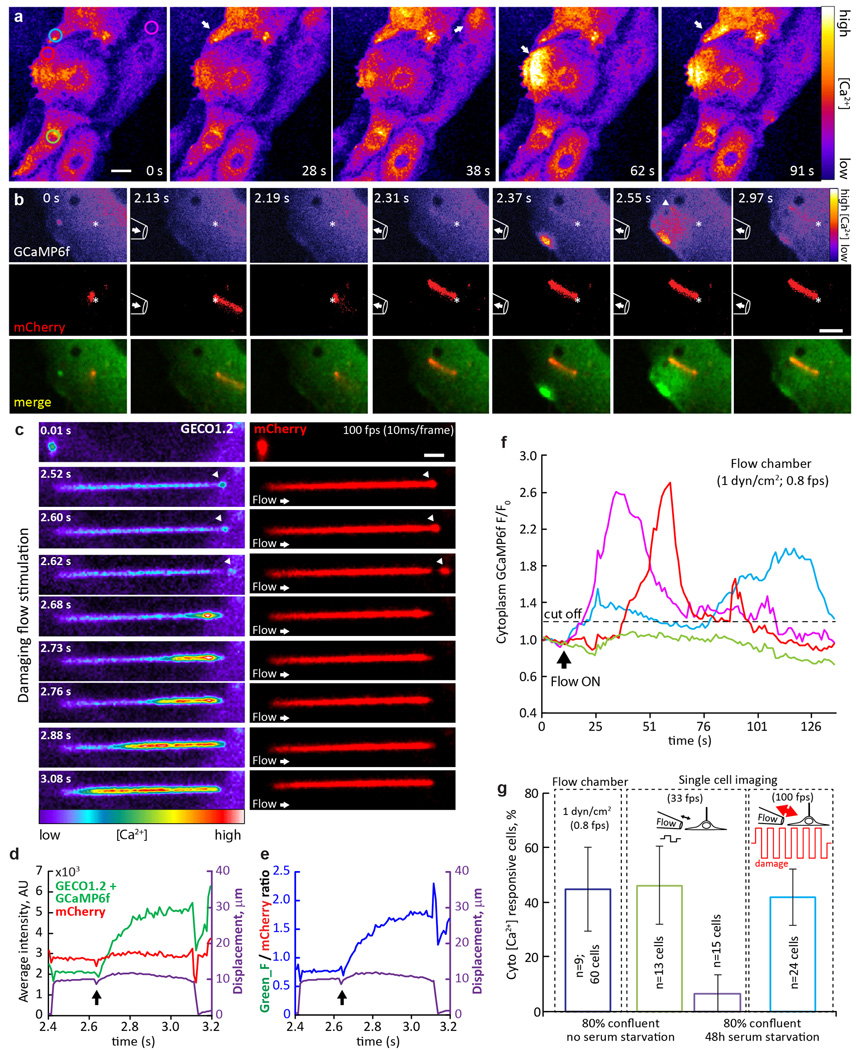

Extended Data Figure 8. Flow-dependent [Ca2+] increases originate in the cytoplasm in MEF cells.

a, Representative image sequence of cultured MEF cells responding to 1 dyn/cm2 fluid flow in a flow chamber. Cells were isolated from E14 Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg:GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg mice, expressing Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2 in primary cilia, and GCaMP6f in the cytoplasm. GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity is presented as pseudocolor heatmap; arrows point to the cells that respond to the flow stimulus, circles indicate ROI used for analysis in f; imaging rate, 0.6 fps; scale bar, 10 µm. Representative of 19 videos × 60 frames. b-b”, Representative image sequence of cultured MEF cell responding to a single cycle of oscillatory fluid flow (OscFF 16). Top row: GCaMP6f + GECO1.2 fluorescence intensity presented as pseudocolor heatmap; Middle row: mCherry fluorescence; Bottom row: merged GCaMP6f + GECO1.2 (green) and mCherry (red) signals. Left panel, b, average of ~10 consecutive frames before stimulus application; 1.2 s into the experiment, an alternating pressure stimulus was applied to the cell membrane, away from the cilium (positive, then negative, ~1.5 s each, diagram shown in b’). Following the stimulus (b”; each image is an average of 3–5 consecutive frames at the time point reflected on the image), a Ca2+ wave originating from the plasma membrane/cytoplasm spreads across the cell body. As seen on the image sequence, a single cycle of strong OscFF application to the cell membrane initiates a Ca2+ increase in the cytoplasm (whether from across the plasma membrane or from intracellular stores was not determined). Negligible cilium movement has been detected in this particular case (~200 nm, grey trace in c), as the cilium was located under the cell, between the cell and the coverslip. Scale bar, 5 µm. Representative of 40 videos × 450 frames. c, Quantification of (F_GECO1.2 + F_GCaMP6f), green and F_mCherry, red, channel intensities in the cilium in b. The ROI was identified frame-by-frame by a MATLAB tracking algorithm and average fluorescence plotted as a function of time. Cilium ROI displacement is superimposed in grey. d, Average GCaMP6f (cytoplasm) fluorescence intensity in the ROI depicted in b” (white circle), superimposed with ciliary (F_GECO1.2 + F_GCaMP6f)/F_mCherry ratio (purple trace) showing an earlier Ca2+ onset for the cytoplasmic GCaMP6f indicator. Dashed box outlines the data shown in e. e, Same as in c, but with higher time resolution. Ciliary [Ca2+] increase is ~200 ms delayed from the cytoplasmic Ca2+ increase, showing the necessity for high imaging rates for Ca2+ imaging of cilia. f, Quantification of GCaMP6f fluorescent intensity change over time for 4 cells from a; ROIs depicted in a. Dashed line: Threshold for labeling a cell as responsive (20% change in fluorescent intensity). All selected cells except that represented by the magenta trace, responded to the flow. g, MEF cell response rate in flow chamber and pipette flow application experiments. Blue and red bars represent 1 dyn/cm2 application in flow chamber experiments; ~40% of the cells responding to the flow. Apyrase (7 unit/ml) application did not change the response rate, suggesting that ATP release is not a major contributor to flow-induced Ca2+ response in this cell type. Remaining bars represent single cell imaging experiments with local flow delivery via pipette, using cells in 3 conditions: low confluency cells (~15%), with 24 h (green bar) and 48 h (purple bar) serum starvation to promote cilia formation, and highly confluent coverslips without serum starvation (light blue bar). Arrest of MEF cells in G0 sensitizes cells to respond to flow stimulus with intracytoplasmic Ca2+ changes. All error bars ± SEM.

Extended Data Figure 9. Flow-dependent [Ca2+] increases originate in the cytoplasm in primary mIMCD cells.

a, Cultured primary mIMCD cells, isolated from Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg:GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg mice, respond to 1 dyn/cm2 shear stress in a flow chamber. GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity is presented as pseudocolor heatmap, arrows point to the cells that respond to the flow stimulus; Imaging rate, 0.8 fps; scale bar, 10 µm. Representative of 6 videos × 100 frames. Circles indicate ROI’s used for analysis in f. b, Cultured mIMCD cell with cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations following flow application. Pipette outline on the image represents its approximate position, an arrow inside the pipette represents the direction of the flow. An alternating flow stimulus deflects the primary cilium (red) in positive and negative directions. This deflects the cell membrane, resulting in Ca2+ increases in the cytoplasm. Although it is well known that mechanical force can initiate increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+, there are several potential sources (plasma membrane rupture, mechanosensitive ion channels, ATP release and purinergic receptor activation, intracellular Ca2+ stores) that appear to depend on cell type and conditions. No change in ciliary [Ca2+] is evident until the cytoplasmic Ca2+ reaches the cilium (arrowhead, 2.55 s). Top row: GCaMP6f + GECO1.2 fluorescence intensity presented as a pseudocolor heatmap; Middle row, mCherry signal intensity; Bottom row, merged GCaMP6f+GECO1.2 (green) and mCherry (red) fluorescence signals. Asterisks indicate the base of the cilium. Imaging rate, 33 fps; scale bar, 5 µm. Representative of 17 videos × 450 frames. c, Fast imaging during supraphysiological flow application to primary cilium of cultured mIMCD cells reveals ciliary damage and subsequent increase of ciliary [Ca2+]. GCaMP6f+GECO1.2 fluorescence intensity, pseudocolor heatmap (left); mCherry signal, red (right). At flow rates greater than 10 times those used for ciliary deflection, the ciliary membrane disintegrates and distal parts of the cilium (arrowheads) detach. Following ciliary tip damage, Ca2+ enters the cilium from the break point. Ciliary Ca2+ influx does not occur before detachment of ciliary tip, presumably when the membrane experiences the highest force and stretch, Arrow: direction of the flow. Imaging rate, 100 fps; Scale bar, 2 µm. Representative of 13 videos × 3000 frames. d–e, Quantification of GCaMP6f+GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence intensities from the cilium in c. Arrow, ciliary tip detachment event. The ROI was identified frame-by-frame by a MATLAB tracking algorithm and GECO1.2 and mCherry fluorescence, d, and ratio, e, plotted as a function of time. Cilium ROI displacement is superimposed (purple). f, Quantification of GCaMP6f + GECO1.2 fluorescence intensity change over time for 4 representative cells in a; ROIs depicted in a (left panel). Dashed line, 20% threshold defining responsive cells. All selected cells (except that represented by the green trace) responded to flow. g, Cultured primary mIMCD cell response rate in flow chamber and pipette flow application experiments. Blue bar, flow application performed in a flow chamber; ~46% of the cells respond to 1 dyn/cm2 shear stress. Green and purple bars represent single cell imaging experiments for highly confluent cells (~80%), without (green bar) or following (purple bar) 48 h serum starvation. Light blue bar, cells following 48 h serum starvation in response to damaging flow stimulus. All error bars ± SEM.

Extended Data Figure 10. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ signaling in the embryonic node of Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg: GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg embryos.

a–a”, Representative images of embryos within the developmental window used: from early bud (EB, a), early headfold (EHF, a’) to 2–3 somite stage (2–3S, a”). Scale bars, 200 µm. Each panel is a representative of ≥ 5 images. b, Drawing (top) and image (bottom) of the embryo mounting plate used for imaging. Scale bar, 10 mm. c, Embryos were mounted with the node facing up. Pipette used for cilia deflection is shown in blue. d, DIC image of embryo with the node outlined by the dashed line. Scale bar, 100 µm. Representative of 14 images. e, Representative image of an embryonic node of an Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg:GCaMP6ftg:E2a-Cretg EHF embryo, expressing GCaMP6f in the cytoplasm to visualize cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations. Scale bar, 20 µm. Representative of 3 videos × 300 frames. f, Mapping of cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations in close proximity to the embryonic node. Only ΔF/F > 30% were included in the analysis. Nodal perimeter is outlined with white dashed line. g, Quantification of cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals shown in (e, f) occurring within 0.01 mm2 on either the left or the right side of the embryonic node. Left side: 8.3 ± 2.3 min−1, right side: 7.6 ± 1.2 min−1, n = 5 embryos; this difference was not statistically significant between the late bud (LB) and late headfold (LHF) stage see also ref.33 (Supplementary Video 10). h–i, Average ratio changes (F_GECO1.2/F_mCherry) of crown cell primary cilia from the left side of the embryonic node of Arl13b-mCherry-GECO1.2tg/tg:GCaMP6f:E2a-Cretg expressing EHF embryos during the application of physiological levels of flow (slow deflection; note longer imaging time of 15 s). Flow velocity, calibrated in-frame using fluorescent beads, was slowly increased (ramped); see also Fig. 4 k–l. Cilia were divided into two groups: h, the average ratio change for displaced cilia (n=34 cilia from 5 embryos; average centroid displacement was 409 ± 35 nm); i, the average ratio change for nondisplaced cilia (n = 23 cilia from 5 embryos). All error bars ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Mouse Gene Manipulation Facility of the Boston Children’s Hospital Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC; NIHP30-HD 18655), NIH 5R01 DC000304 to DPC, and the Kaplan Family for financial support to M.D. We thank Jaime Rivera (UMass Medical Center), Jesse Angelo, Jesse Mager and Kim Tremblay (UMass, Amherst) for help with developmental staging of mouse embryos, Larry Palmer and Gustavo Frindt (Weil Cornell Medical College) for teaching M.D. the kidney tubule dissection, Alan Weinstein (Weil Cornell Medical College) for helpful discussions of fluid velocities in kidney tubules, W. Fowle (Northeastern University) for access to the SEM facility, R. Stepanyan (Case Western) and J. Shen (HMS) for help with statistics, and members of the Clapham and Corey labs for advice and discussion. We thank Hongkui Zeng (Allen Institute) for the Ai95 mouse line, Lynda Bonewald (UMKC) for the MLO-Y4-cell line, Paola Divieti Pajevic and Jordan Spatz (Massachusetts General Hospital) for the Ocy454 cell line and Timur Indzhykulian for support. D.E.C. and D.P.C. are Investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author contributions

MD and AAI carried out the experiments. XL and YL helped with experiments; TX developed software for analysis. MD, AAI, DPC, and DEC analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Author Information The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Zimmerman K, Yoder BK. SnapShot: Sensing and Signaling by Cilia. Cell. 2015;161:692–692. e691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamada H. Role of physical forces in embryonic development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;47–48:88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, Elia AE, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet. 2003;33:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corey DP, Hudspeth AJ. Ionic basis of the receptor potential in a vertebrate hair cell. Nature. 1979;281:675–677. doi: 10.1038/281675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corey DP, Hudspeth AJ. Response latency of vertebrate hair cells. Biophys J. 1979;26:499–506. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85267-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sellick PM, Patuzzi R, Johnstone BM. Measurement of basilar membrane motion in the guinea pig using the Mossbauer technique. J Acoust Soc Am. 1982;72:131–141. doi: 10.1121/1.387996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beurg M, Fettiplace R, Nam JH, Ricci AJ. Localization of inner hair cell mechanotransducer channels using high-speed calcium imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:553–558. doi: 10.1038/nn.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kindt KS, Finch G, Nicolson T. Kinocilia mediate mechanosensitivity in developing zebrafish hair cells. Dev Cell. 2012;23:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Bending the MDCK cell primary cilium increases intracellular calcium. J Membr Biol. 2001;184:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of rat ascending Henle limb III. Tubular function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F543–F556. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00232.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz EA, Leonard ML, Bizios R, Bowser SS. Analysis and modeling of the primary cilium bending response to fluid shear. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F132–F138. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.1.F132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young YN, Downs M, Jacobs CR. Dynamics of the primary cilium in shear flow. Biophys J. 2012;103:629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AbouAlaiwi WA, Takahashi M, Mell BR, Jones TJ, Ratnam S, Kolb RJ, Nauli SM. Ciliary polycystin-2 is a mechanosensitive calcium channel involved in nitric oxide signaling cascades. Circ Res. 2009;104:860–869. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin X, Mohieldin AM, Muntean BS, Green JA, Shah JV, Mykytyn K, Nauli SM. Cilioplasm is a cellular compartment for calcium signaling in response to mechanical and chemical stimuli. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2165–2178. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su S, Phua SC, DeRose R, Chiba S, Narita K, Kalugin PN, Katada T, Kontani K, Takeda S, Inoue T. Genetically encoded calcium indicator illuminates calcium dynamics in primary cilia. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1105–1107. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KL, Guevarra MD, Nguyen AM, Chua MC, Wang Y, Jacobs CR. The primary cilium functions as a mechanical and calcium signaling nexus. Cilia. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13630-015-0016-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delling M, DeCaen PG, Doerner JF, Febvay S, Clapham DE. Primary cilia are specialized calcium signalling organelles. Nature. 2013;504:311–314. doi: 10.1038/nature12833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor AK, Malarkey EB, Berbari NF, Croyle MJ, Haycraft CJ, Bell PD, Hohenstein P, Kesterson RA, Yoder BK. An inducible CiliaGFP mouse model for in vivo visualization and analysis of cilia in live tissue. Cilia. 2013;2:8. doi: 10.1186/2046-2530-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JD, Anderson KV. Morphogenesis of the node and notochord: the cellular basis for the establishment and maintenance of left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3464–3476. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada Y, Takeda S, Tanaka Y, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Hirokawa N. Mechanism of nodal flow: a conserved symmetry breaking event in left-right axis determination. Cell. 2005;121:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Takeda S, Harada A, Kanai Y, Kido M, Hirokawa N. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell. 1998;95:829–837. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nonaka S, Shiratori H, Saijoh Y, Hamada H. Determination of left-right patterning of the mouse embryo by artificial nodal flow. Nature. 2002;418:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature00849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshiba S, Shiratori H, Kuo IY, Kawasumi A, Shinohara K, Nonaka S, Asai Y, Sasaki G, Belo JA, Sasaki H, Nakai J, Dworniczak B, Ehrlich BE, Pennekamp P, Hamada H. Cilia at the node of mouse embryos sense fluid flow for left-right determination via Pkd2. Science. 2012;338:226–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1222538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath J, Somlo S, Makova S, Tian X, Brueckner M. Two populations of node monocilia initiate left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. FGF-induced vesicular release of Sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid in leftward nodal flow is critical for left-right determination. Nature. 2005;435:172–177. doi: 10.1038/nature03494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada Y, Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Saijoh Y, Hamada H, Hirokawa N. Abnormal nodal flow precedes situs inversus in iv and inv mice. Mol Cell. 1999;4:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao R, Xu XZ. Mechanosensitive channels: in touch with Piezo. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R936–R938. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connelly T, Yu Y, Grosmaitre X, Wang J, Santarelli LC, Savigner A, Qiao X, Wang Z, Storm DR, Ma M. G protein-coupled odorant receptors underlie mechanosensitivity in mammalian olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:590–595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418515112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iskratsch T, Wolfenson H, Sheetz MP. Appreciating force and shape-the rise of mechanotransduction in cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:825–833. doi: 10.1038/nrm3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma M, Tian X, Igarashi P, Pazour GJ, Somlo S. Loss of cilia suppresses cyst growth in genetic models of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1004–1012. doi: 10.1038/ng.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for Methods and SI

- 31.Faust D, Geelhaar A, Eisermann B, Eichhorst J, Wiesner B, Rosenthal W, Klussmann E. Culturing primary rat inner medullary collecting duct cells. J Vis Exp. 2013 doi: 10.3791/50366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer LG, Frindt G. Gating of Na channels in the rat cortical collecting tubule: effects of voltage and membrane stretch. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:35–45. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takao D, Nemoto T, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Kajiura-Kobayashi H, Shiratori H, Nonaka S. Asymmetric distribution of dynamic calcium signals in the node of mouse embryo during left-right axis formation. Dev Biol. 2013;376:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downs KM, Davies T. Staging of gastrulating mouse embryos by morphological landmarks in the dissecting microscope. Development. 1993;118:1255–1266. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshiba S, Hamada H. Roles of cilia, fluid flow, and Ca2+ signaling in breaking of left-right symmetry. Trends Genet. 2014;30:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T, Campbell RE. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca(2)(+) indicators. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spatz JM, Wein MN, Gooi JH, Qu Y, Garr JL, Liu S, Barry KJ, Uda Y, Lai F, Dedic C, Balcells-Camps M, Kronenberg HM, Babij P, Pajevic PD. The Wnt Inhibitor Sclerostin Is Up-regulated by Mechanical Unloading in Osteocytes in Vitro. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:16744–16758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.628313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao Z, Zhang S, Mahlios J, Zhou G, Magenheimer BS, Guo D, Dallas SL, Maser R, Calvet JP, Bonewald L, Quarles LD. Cilia-like structures and polycystin-1 in osteoblasts/osteocytes and associated abnormalities in skeletogenesis and Runx2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30884–30895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604772200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Indzhykulian AA, Stepanyan R, Nelina A, Spinelli KJ, Ahmed ZM, Belyantseva IA, Friedman TB, Barr-Gillespie PG, Frolenkov GI. Molecular remodeling of tip links underlies mechanosensory regeneration in auditory hair cells. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeCaen PG, Delling M, Vien TN, Clapham DE. Direct recording and molecular identification of the calcium channel of primary cilia. Nature. 2013;504:315–318. doi: 10.1038/nature12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagasawa H, Miyamoto M, Fujimoto M. [Reproductivity in inbred strains of mice and project for their efficient production (author’s transl)] Jikken Dobutsu. 1973;22:119–126. doi: 10.1538/expanim1957.22.2_119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan S, Zhao L, Brueckner M, Sun Z. Intraciliary calcium oscillations initiate vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Curr Biol. 2015;25:556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, Bargmann CI, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Looger LL. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan B, Geleoc GS, Asai Y, Horwitz GC, Kurima K, Ishikawa K, Kawashima Y, Griffith AJ, Holt JR. TMC1 and TMC2 are components of the mechanotransduction channel in hair cells of the mammalian inner ear. Neuron. 2013;79:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodyear RJ, Forge A, Legan PK, Richardson GP. Asymmetric distribution of cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 in the kinocilial links of avian sensory hair cells. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:4288–4297. doi: 10.1002/cne.22456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beurg M, Xiong W, Zhao B, Muller U, Fettiplace R. Subunit determination of the conductance of hair-cell mechanotransducer channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:1589–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420906112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webb SW, Grillet N, Andrade LR, Xiong W, Swarthout L, Della Santina CC, Kachar B, Muller U. Regulation of PCDH15 function in mechanosensory hair cells by alternative splicing of the cytoplasmic domain. Development. 2011;138:1607–1617. doi: 10.1242/dev.060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lelli A, Asai Y, Forge A, Holt JR, Geleoc GS. Tonotopic gradient in the developmental acquisition of sensory transduction in outer hair cells of the mouse cochlea. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2961–2973. doi: 10.1152/jn.00136.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weinstein AM. Insights from mathematical modeling of renal tubular function. Exp Nephrol. 1998;6:462–468. doi: 10.1159/000020556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baines AD, de Rouffignac C. Functional heterogeneity of nephrons. II. Filtration rates, intraluminal flow velocities and fractional water reabsorption. Pflugers Arch. 1969;308:260–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00586558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olesen SP, Clapham DE, Davies PF. Haemodynamic shear stress activates a K+ current in vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;331:168–170. doi: 10.1038/331168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.