Abstract

Objective

Rumination, a perseverative cognitive process that involves repetitively and passively focusing on negative emotions, is a transdiagnostic risk factor for the development of psychopathology. Although rumination has been linked to various forms of psychopathology including depression, anxiety and alcohol misuse, little is known about the conditions that lead to multifinality. Here, we test putative moderators (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011) of the association between rumination and subsequent internalizing symptoms and frequency of alcohol use during adolescence.

Method

Participants included 388 youth (52% girls; 90% Caucasian) in a longitudinal birth cohort study who completed questionnaires in Grades 9 and 11.

Results

Brooding, a maladaptive form of rumination measured in Grade 9, was associated with greater internalizing symptoms in Grade 11, and greater perceived peer rejection in Grade 9 amplified this association. Brooding was also associated with greater frequency of alcohol use among adolescents who reported having more friends who use alcohol. Gender differences were also examined.

Conclusions

Findings provide support for some of the predictions regarding moderators of multifinality made by Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins. Implications of understanding divergent trajectories in the prevention of psychopathology are discussed.

Keywords: rumination, multifinality, internalizing, alcohol use, adolescence

Rumination is a transdiagnostic risk factor associated with a variety of outcomes among youth and adults including depression (for a review see Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lybomirsky, 2008), anxiety (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011), self-injurious behavior (e.g., Hilt, Cha, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008), binge eating and drinking (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007), and comorbid aggression (McLaughlin, Aldao, Wisco, & Hilt, 2014). Although rumination is an important risk factor for the development of psychopathology, little is known about the conditions under which rumination leads to multiple, maladaptive outcomes, i.e., multifinality. Understanding how divergent trajectories develop offers additional pathways for prevention and intervention.

Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) identified types of moderating factors that may determine whether rumination leads to depression, anxiety, substance misuse, or bulimia nervosa. These moderators may lead to psychopathology by highlighting themes that are amplified by rumination or by affecting the reinforcement value or conditioning of responses (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). For example, an individual who ruminates may develop depression if he or she experiences loss or failure events that are perseverated on. Another individual who ruminates may develop substance use problems if he or she has a high reward-sensitivity to substances or is exposed to or reinforced for substance use. Although rumination has been associated, concurrently and prospectively, with a variety of deleterious outcomes, the divergent pathways by which rumination may confer greater risk to specific types of psychopathology have not been tested. The present study examines whether moderators proposed by Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) help explain the multifinality of rumination. Specifically, we examine factors that may account for the development of two common symptom profiles during adolescence—internalizing symptoms and alcohol use.

Rumination and Internalizing Symptoms

The association between rumination and depressive and anxiety symptoms has been well studied. One meta-analysis examining the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms among youth samples found a moderate effect size for rumination prospectively predicting depressive symptoms (Rood, Bogels, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schouten, 2009). Although less examined, several studies have found that rumination prospectively predicts anxiety (e.g., Schwartz & Koenig, 1996), and statistically explains the comorbidity between depressive and anxiety symptoms (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011).

Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) speculated that individuals with certain life experiences might be more prone to developing internalizing symptoms following rumination. Specifically, individuals who ruminate might be more at risk for depression following rejection events and more at risk for anxiety following social stress, because they will perseverate on these experiences. Peer rejection, a form of social stress, has been identified as an important risk factor for the development of internalizing symptoms during adolescence (e.g., McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, 2009; Pedersen, Vitaro, Barker, & Borge, 2007). While most adolescents will experience negative emotions following perceived rejection, many will do so only temporarily; adolescents who ruminate, however, are more likely to continue perseverating on the perceived rejection (Hilt & Pollak, 2013). Rumination regarding perceived peer rejection may be especially detrimental for adolescent girls who place a high value on peer relationships (Rose & Rudolph, 2006).

Rumination and Alcohol Use

A smaller literature has focused on the role of rumination in the development of escapist behaviors like alcohol use. Concurrent associations between brooding, a maladaptive component of rumination,1 and substance use problems have been documented among adolescents (Willem, Bijttebier, Claes, & Raes, 2011). Other studies have found that rumination prospectively predicts substance use problems during adolescence (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007). Additional work has associated specific types of rumination with undergraduate alcohol use (e.g., Ciesla, Dickson, Anderson, & Neal, 2011).

Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) suggested that ruminators whose social environments expose them to and reinforce them for substance use would be more likely to use substances when they ruminate. Adolescents who ruminate may find that alcohol helps them to temporarily escape from negative thoughts. Having friends who use substances is a strong predictor of the development of substance use for adolescents (e.g., Wills & Cleary, 1999), and this peer socialization effect is well-documented for alcohol use (e.g., Armstrong, Ruttle, Burk, Costanzo, Strauman, & Essex, 2013; Curran, Stice, & Chassin, 1997). Thus, ruminative adolescents who are exposed to friends who use alcohol may be more likely to see alcohol use as a normative way to escape their ruminative distress, leading to the development of alcohol misuse (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). This effect may be particularly strong for boys who are more likely to use alcohol than girls due to relatively increased risk factors and decreased protective factors (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2006).

The Present Study

In the present study, we tested putative moderators of the association between rumination and subsequent internalizing symptoms and frequency of alcohol use. We hypothesized that perceived peer rejection would strengthen the association between rumination and internalizing symptoms, while having friends who use alcohol would strengthen the association between rumination and frequency of alcohol use. We also tested sex differences in these associations and expected the former model to be stronger for girls and the latter to be stronger for boys. We measured rumination and putative moderators in Grade 9 and predicted outcomes in Grade 11, controlling for Grade 9 levels on these outcomes. This developmental period was chosen based on the typically observed increase in both internalizing symptoms and alcohol use (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998; Thompson, Stockwell, Leadbeater, & Homel, 2014).

Method

Participants

Participants included adolescents (N=388; 52% girls) who participated in the Grade 9 and 11 assessments of the longitudinal Wisconsin Study of Families and Work. Originally, participants’ parents (i.e., 570 pregnant women and their partners) were recruited from clinics in two Midwestern cities for a study on maternity leave (see Hyde, Klein, Essex, & Clark, 1995). Most parents were married (96%) and Caucasian (90%); median annual family income was $47,750 (range from $10,000 to $200,000).

Data for the present study were collected when children were in the spring of grades 9 (Mage=15.26, SD=.34), and 11 (Mage=17.22, SD=.32); 90% of the sample participated at both time points. There were no differences in Grade 9 study variables between those who remained across both time periods and those lost to attrition, t(386)=.30–1.30, ns.

Adolescents completed self-report questionnaires at home and received monetary compensation for their participation. All study procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin; informed consent was obtained from all mothers, and adolescent assent was obtained.

Measures

Rumination

In Grade 9, participants completed a version of the Ruminative Response Scale (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), modified for adolescents to report on their habitual responses to feeling “upset” rather than “depressed,” in line with current conceptualizations (Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). For each item, participants rated how often they respond that way on a 4-point scale (1=almost never; 4=almost always). The mean of the 5 brooding items (e.g., “Think ‘Why do I always react this way?”’) was calculated.1 This scale has demonstrated good internal consistency and predictive validity in studies of adolescents (e.g., Burwell & Shirk, 2007). Internal consistency for the sample was good (α =.82).

Internalizing symptoms

In Grades 9 and 11, participants completed the adolescent version of the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (Burk et al., 2011; Essex et al., 2002). The generalized anxiety (15 items; e.g., “I (don’t) worry bad things are going to happen.”) and depression (15 items, e.g., “I (don’t) have fun in many things.”) subscales were highly correlated (rs>.78, p<.001) at each time point; thus, we created an average internalizing symptom score for Grade 9 (α=.93) and another for Grade 11 (α=.93). Responses are coded on a 6-point scale and computed as a mean score.

Alcohol Use

In Grades 9 and 11, participants reported on their frequency of alcohol use. They were asked if they ever had a drink of alcohol (i.e., “beer, wine, wine coolers, or hard liquor”) and if so, on how many days in the last month (30 days) they had an alcoholic drink. Frequencies for each response option at grades 9 and 11, respectively, were 74.9 and 54.8% (0=None), 17.6 and 24.9% (1.5=1 or 2 days), 2.9 and 12.7% (4=3 to 5 days), 4.3 and 4.6% (7.5=6 to 9 days), 3.0 and 1.7% (14.5=10 to 19 days), and 0 and 0.3% (25.5=20 to 31 days). Although number of drinks per occasion is often a better indicator of risk for alcohol use consequences, frequency may be more related to emotion regulation (e.g., Britton, 2004) and has been prospectively associated with alcohol use disorders (Thompson et al., 2014).

Perceived peer rejection

In Grade 9, participants reported on the degree to which they felt accepted or rejected by peers using the Peer Accept/Reject subscale (5 items, e.g., “Other kids (don’t) ask me to do things with them”; α=.86) from the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (Burk et al., 2011; Essex et al., 2002). Higher scores indicate a higher degree of peer rejection.

Exposure to friends who use alcohol

In Grade 9, participants reported on the use of alcohol by their friends via an adaptation of the Self-Report of Close Friends from the Seattle Social Development Project (O’Donnell, Hawkins, & Abbott, 1995). Adolescents were asked to “please indicate how many of your friends participate in each of the following activities… About how many of your friends drink alcohol?” Adolescents selected one of five options, coded as 0 (none; 34.4%), 1 (1 or 2; 25.4%), 2 (some; 25.1%), 3 (most; 13.9%) and 4 (all; 1.2%). Research has indicated that, on average, adolescents do not significantly over- or under-estimate friends’ behavior compared to friend-report (e.g., Prinstein & Wang, 2005)

Data Analytic Plan

We conducted two hierarchical multiple regression analyses. In testing the hypothesis that peer rejection would moderate the association between rumination and internalizing symptoms, we specified a model predicting internalizing symptoms in Grade 11, controlling for baseline levels of both outcomes (i.e., Grade 9 internalizing symptoms and alcohol use) on Step 1. We entered main effects on Step 2 (Rumination, Peer Rejection, and Sex) and 2-way interactions on Step 3 (Rumination × Peer Rejection, Rumination × Sex, and Peer Rejection × Sex). The 3-way interaction (Rumination × Peer Rejection × Sex) was entered on the final Step. A similar model was specified to test our prediction that having friends who use alcohol would moderate the association between rumination and alcohol use frequency. Predicting frequency of alcohol use at Grade 11, we controlled for Grade 9 alcohol use and internalizing symptoms on Step 1. We entered main effects on Step 2 (Rumination, Exposure to Friends who Use Alcohol, and Sex), 2-way interactions on Step 3 (Rumination × Friends Alcohol, Rumination × Sex, and Friends Alcohol × Sex), and the 3-way interaction on Step 4 (Rumination × Friends Alcohol × Sex). We also tested the specificity of each model by repeating analyses with alternate moderators (i.e., friends’ alcohol use predicting internalizing symptoms and peer rejection predicting alcohol use). We mean-centered predictor and moderator variables prior to testing and probed significant interactions using simple slopes at one standard deviation above and below the mean (Aiken & West, 1991) using PROCESS for SPSS (Hayes, 2014).

To account for missing data, we used multiple imputation (fully conditional specification) in SPSS. This is a recommended approach because of its sophistication and utility for attrition (Enders, 2013). The procedure generates multiple estimates of missing data points, and we report pooled estimates.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and sex differences are presented in Table 1.2 Girls reported significantly higher levels of rumination and internalizing symptoms compared to boys. Bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Sex Differences

| Study Variables | Boys’ M (SD) n = 186 |

Girls’ M (SD) n = 202 |

t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 9 Rumination | 1.92 (.60) | 2.24 (.74) | 4.68** | .48 |

| Grade 9 Internalizing | 2.11 (.58) | 2.28 (.69) | 4.65** | .27 |

| Grade 11 Internalizing | 2.23 (.62) | 2.33 (.68) | 2.64* | .15 |

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | .81 (1.82) | .73 (1.90) | −.39 | −.04 |

| Grade 11 Alcohol Use | 2.61 (5.33) | 2.33 (5.36) | −.51 | −.05 |

| Grade 9 Peer Rejection | 5.13 (.75) | 5.17 (.70) | .48 | .03 |

| Grade 9 Exposure to Friends’ Alcohol Use | 1.26 (1.09) | 1.19 (1.13) | −.66 | −.03 |

Note.

p < .01;

p < .001.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Grade 9 Rumination | -- | |||||

| 2. Grade 9 Internalizing | .56** | -- | ||||

| 3. Grade 11 Internalizing | .43** | .72** | -- | |||

| 4. Grade 9 Alcohol Use | .08 | .11* | .08 | -- | ||

| 5. Grade 11 Alcohol Use | .08 | .07 | .17** | .25** | -- | |

| 6. Grade 9 Peer Rejection | .10 | .36** | .22** | −.10* | −.16** | -- |

| 7. Grade 9 Friends Alcohol | .17** | .19** | .18** | .47** | .35** | .17** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01

Hypothesis Testing

Does perceived peer rejection moderate the association between rumination and internalizing symptoms?

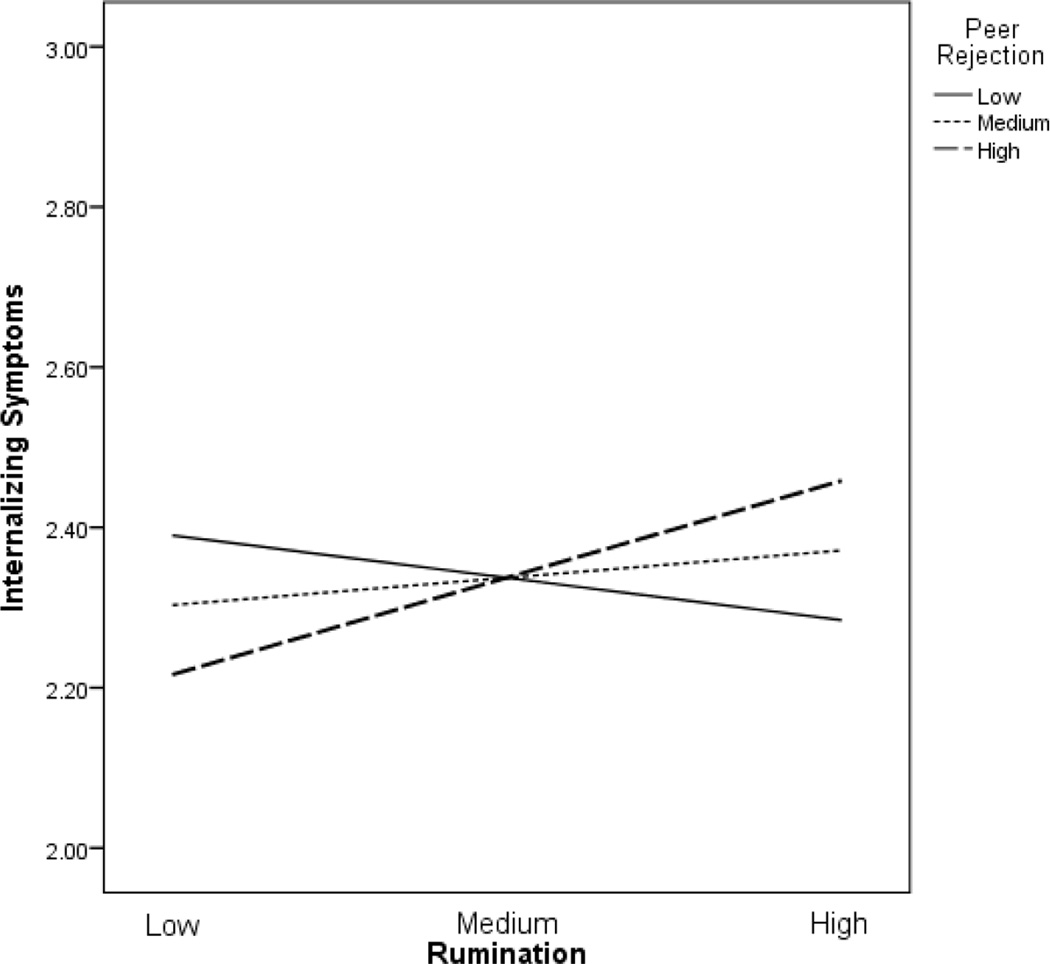

In the regression predicting Grade 11 internalizing symptoms, Step 3, containing the 2-way interactions, was significant, with the interaction between rumination and peer rejection a significant predictor in the model (see Table 3), supporting the first hypothesis. The slope for high levels of perceived peer rejection was significant (t = 3.09, p = .002), but the slopes for low (t = −1.43, p = .153) and medium (t = 1.18, p = .238) levels were not, suggesting that the association between rumination and internalizing symptoms holds only for adolescents who experienced higher perceived peer rejection (see Fig. 1). The 3-way interaction including sex in Step 4 was not significant.

Table 3.

Regression Predicting Internalizing Symptoms in Grade 11

| Predictors | R2 |

F for increment in R2 |

B | SE |

t for within-set predictors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .52 | 205.02*** | |||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .70 | .04 | 18.33*** | ||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | −.00 | .01 | −.21 | ||

| Step 2 | .52 | .96 | |||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .71 | .05 | 13.47*** | ||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | −.01 | .02 | −.36 | ||

| Grade 9 Rumination | . 02 | .05 | .51 | ||

| Grade 9 Peer Rejection | .03 | .04 | .64 | ||

| Sex | −.04 | .05 | −.84 | ||

| Step 3 | .54 | 6.12*** | |||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .68 | .05 | 13.14*** | ||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | −.00 | .01 | −.20 | ||

| Grade 9 Rumination | .09 | .08 | 1.10 | ||

| Grade 9 Peer Rejection | .07 | .05 | 1.45 | ||

| Sex | −.05 | .05 | −.89 | ||

| Rumination × Peer Rejection | . 16 | .06 | 2.74** | ||

| Rumination × Sex | −.09 | .09 | −.93 | ||

| Peer Rejection × Sex | −.13 | .08 | −1.63 | ||

| Step 4 | .54 | .07 | |||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .68 | .05 | 13.07*** | ||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | −.00 | .01 | −.21 | ||

| Grade 9 Rumination | .09 | .08 | 1.10 | ||

| Grade 9 Peer Rejection | .07 | .05 | 1.45 | ||

| Sex | −.05 | .05 | −.87 | ||

| Rumination × Peer Rejection | .16 | .08 | 2.04* | ||

| Rumination × Sex | −.09 | .09 | −.93 | ||

| Peer Rejection × Sex | −.13 | .08 | −1.70 | ||

| Rumination × Peer Rejection × Sex | −.00 | .13 | −.01 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p<.001.

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of perceived peer rejection on the relationship between rumination and internalizing symptoms. “Low” represent 1 SD below the mean, “medium” represents the mean, and “high” represents 1 SD above the mean. Only the slope for high peer rejection is significant.

Does exposure to friends who use alcohol moderate the association between rumination and alcohol use?

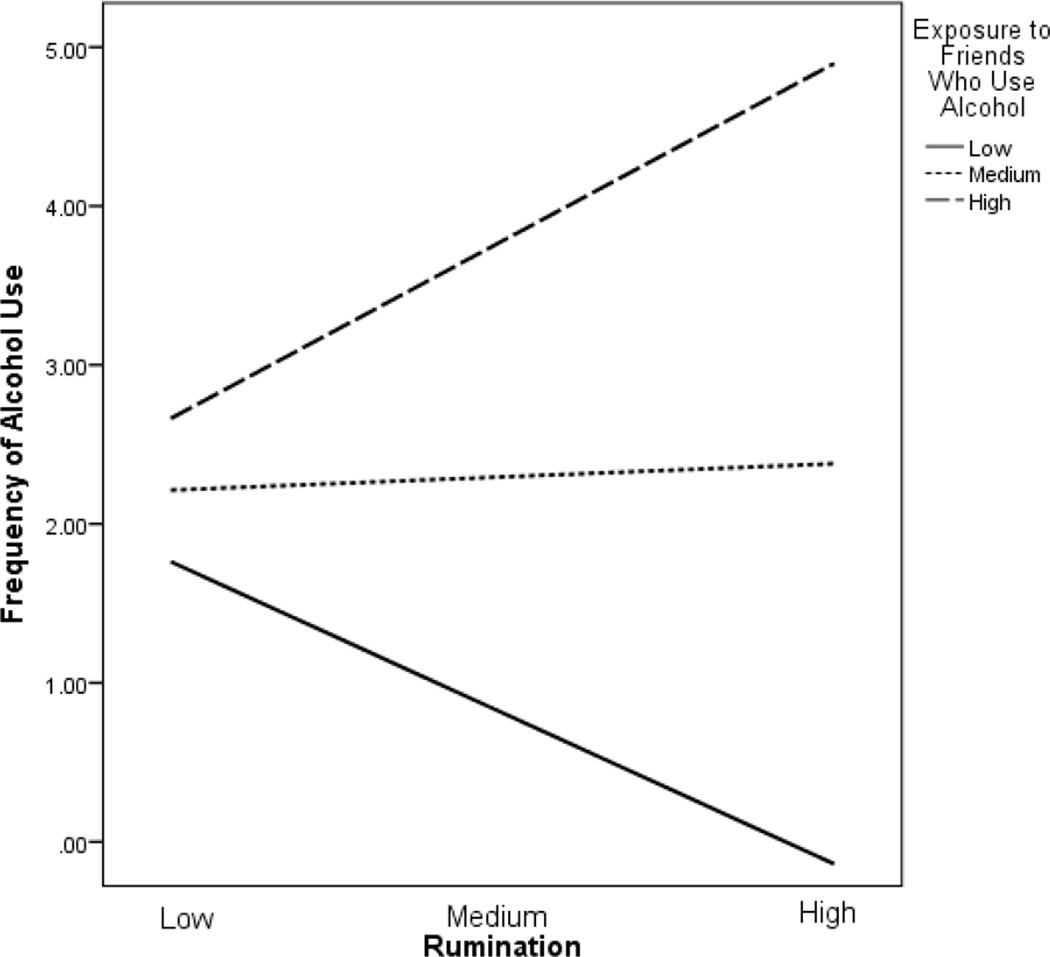

In the regression predicting Grade 11 frequency of alcohol use, Step 3, containing the 2-way interactions, was significant, with the interaction between rumination and exposure to friends who use alcohol a significant predictor in the model (see Table 4), supporting the second hypothesis. The slopes for both low and high levels of exposure to friends who use alcohol were significant; for low, t = −2.44, p = .015; for high t = 2.97, p = .003. The slope for mean level of exposure to friends who use alcohol was not significant, t = .28, p = .781. This suggests that having more friends who use alcohol amplifies the relationship between rumination and frequency of alcohol use, while exposure to fewer friends who use alcohol dampens this association (see Fig. 2). The 3-way interaction including sex in Step 4 was not significant.

Table 4.

Regression Predicting Alcohol Frequency in Grade 11

| Predictors | R2 |

F for increment in R2 |

B | SE |

t for within- set predictors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .26 | 13.36*** | |||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | .71 | .14 | 4.95*** | ||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .35 | .38 | .90 | ||

| Step 2 | .37 | 10.22*** | |||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | .31 | .16 | 1.99* | ||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | −.07 | .45 | −.15 | ||

| Grade 9 Rumination | .21 | .45 | .47 | ||

| Grade 9 Friends Alcohol | 1.44 | .27 | 5.43*** | ||

| Sex | −.21 | .53 | −.40 | ||

| Step 3 | .46 | 11.50*** | |||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | .34 | .15 | 2.28* | ||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .07 | .43 | .16 | ||

| Grade 9 Rumination | .94 | .63 | 1.48 | ||

| Grade 9 Friends Alcohol | 1.97 | .36 | 5.54*** | ||

| Sex | −.35 | .51 | −.69 | ||

| Rumination × Fr. Alcohol | 1.75 | .32 | 5.44*** | ||

| Rumination × Sex | −1.30 | .76 | −1.71 | ||

| Friends Alcohol × Sex | −1.29 | .47 | −2.75** | ||

| Step 4 | .46 | .08 | |||

| Grade 9 Alcohol Use | .34 | .15 | 2.26* | ||

| Grade 9 Internalizing | .08 | .44 | .18 | ||

| Grade 9 Rumination | .94 | .63 | 1.48 | ||

| Grade 9 Friends Alcohol | 1.99 | .36 | 5.50*** | ||

| Sex | −.33 | .52 | −.64 | ||

| Rumination × Fr. Alcohol | 1.86 | .52 | 3.56*** | ||

| Rumination × Sex | −1.30 | .77 | −2.74** | ||

| Friends Alcohol × Sex | −1.29 | .47 | −1.44 | ||

| Rumination × Fr. Alcohol × Sex | −.19 | .66 | −.29 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p<.001

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of exposure to friends who use alcohol on the relationship between rumination and frequency of alcohol use. “Low” represents 1 SD below the mean, “medium” represents the mean, and “high” represents 1 SD above the mean. The slopes for low and high levels of exposure to friends who use alcohol are significant.

Are the moderators specific to each outcome?

In a model predicting Grade 11 internalizing symptoms using exposure to friends who use alcohol as a moderator, the interaction between rumination and exposure to friends who use alcohol was not significant (t = 1.68, p = .093), suggesting that exposure to friends who use alcohol is a specific moderator of the association between rumination and alcohol use. Similarly, in a model predicting Grade 11 alcohol use using perceived peer rejection as a moderator, the interaction between rumination and peer rejection was not significant (t = 1.40, p = .162), suggesting that perceived peer rejection is a specific moderator of the association between rumination and internalizing symptoms.

Discussion

We found support for putative moderators to explain a pattern of multifinality associated with rumination in previous research. Specifically, we showed that rumination measured in Grade 9 was associated with greater internalizing symptoms at Grade 11 for adolescents reporting higher levels of perceived peer rejection. Rumination in Grade 9 was also associated with greater frequency of alcohol use in Grade 11 for those adolescents reporting more friends who use alcohol.

Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) suggest that interpersonal experiences, such as rejection, will likely lead to depressive symptoms. They further speculate that the experience of rejection, coupled with rumination, will amplify the initial negative mood state caused by the rejection experience (e.g., sadness, anxiety or both). A study of adults found that rumination about an interpersonal offense was associated with depressive symptoms, offering preliminary support for these predictions (Wade, Vogel, Yu-sin Liao, & Goldman, 2008). Here, we found that perceived peer rejection moderated the association between rumination and subsequent internalizing symptoms. Specifically, the association existed only among youth experiencing higher levels of perceived peer rejection. For them only, high levels of rumination predicted more internalizing symptoms whereas low levels of rumination appear to be protective against internalizing symptoms. This potential protective influence is surprising and requires further study to understand whether, among youth high on peer rejection, low levels of rumination are a proxy for another characteristic that would explain why they are aware of rejection but not bothered by it (e.g., asocial). Although we predicted the moderation effect might be stronger for girls due to the value they tend to place on peer relationships (Rose & Rudolph, 2006), there was not a three-way interaction with sex. This suggests that perceived rejection may be equally detrimental to adolescent girls and boys who ruminate.

Regarding the trajectory leading from rumination to alcohol use, Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) suggest that specific environmental or biological moderators are at play. We tested the former prediction that youth who are exposed to alcohol-using friends would consume more alcohol, perhaps as a way to deal with the distress caused by rumination. We found support for this prediction, as the association between rumination and greater frequency of alcohol use was positive for adolescents who reported greater exposure to friends who use alcohol. Ruminating adolescents who were not exposed to friends who use alcohol reported lower frequency of alcohol use, suggesting these ruminators were likely coping in a different way, demonstrating the importance of friendship culture for ruminators. Although we predicted that this association might be stronger for boys due to their greater risk of alcohol use (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2006), there was no three-way interaction with sex, suggesting that exposure to friends who use alcohol may be equally detrimental to adolescent boys and girls who ruminate.

In addition to these novel findings, we replicated and extended previous research regarding outcomes associated with rumination. The bivariate association between rumination and concurrent and prospective internalizing symptoms replicates prior research (e.g., Schwartz & Koenig, 1996), although the association is reduced to non-significance in the regression model when Grade 9 internalizing symptoms (and other Grade 9 variables) are included. Fewer studies have examined the prospective association between rumination and alcohol use. Our finding that rumination predicted greater frequency of alcohol use from Grades 9 to 11 for both girls and boys who reported having relatively more friends who use alcohol replicates and extends the findings from previous research showing an association between rumination and substance abuse more generally during adolescence in a study of only females (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007) and in a mixed-sex study (Willem et al., 2011). To our knowledge, this is the first study of adolescents to link rumination to alcohol use specifically, extending research on adults (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002). It is important to note that rumination did not predict frequency of alcohol use at the bivariate level or as a main effect in the regression model, suggesting that having friends who use alcohol was a necessary condition for this association.

Some limitations of the study are worth noting. Although we found support for predictions and ruled out opposite moderating effects, we only tested a single putative moderator for each association, while Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) proposed multiple putative moderators. Further, the use of self-report data raises the issue of shared method variance and may be especially concerning for assessing peer rejection, as rumination and internalizing symptoms may affect perceptions of rejection. Future research that assesses peer rejection and alcohol use using peer-report would be optimal (Prinstein & Wang, 2005). Interview measures of psychopathology would also aid in reducing shared method variance. An additional limitation is that the study may have been under-powered to detect a three-way interaction, so conclusions about whether these associations are equally strong in boys and girls should be made cautiously.

A particular strength of the study is our focus on adolescence and examination of moderators that are salient during this developmental period. Adolescents place a great deal of importance on peers, shifting from a reliance on parents in childhood (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Thus, it is not surprising that perceived rejection and friends’ alcohol use impacted the relationship between rumination and mental health outcomes.

Understanding the conditions involved in rumination’s mutlifinality offers important pathways for prevention and intervention. First, identification of moderators allows for targeted preventive intervention efforts. Second, although it may be difficult to intervene with environmental circumstances such as peer rejection and exposure to friends who use alcohol, such interventions are possible (e.g., Donaldson, Graham, Piccinin, & Hansen, 1995; Olweus, 1994). Perhaps the most important intervention effort would be to help adolescents to cope with the negative mood states created by rumination or reduce the tendency to ruminate, as rumination is a common denominator in the development of multiple symptom profiles. There are several promising interventions that do this including rumination-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (Watkins et al., 2011) and mindfulness meditation (e.g., Hilt & Pollak, 2012).

In conclusion, we demonstrated that rumination is associated with greater internalizing symptoms and frequency of alcohol use during adolescence and found evidence to support perceived peer rejection and exposure to friends who use alcohol as moderators for these associations, respectively. Understanding the conditions of multifinality offers multiple pathways for intervention, and future research should further examine these conditions in a developmental context.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health grants R01-MH044340, P50-MH052354, P50-MH069315, P50-MH084051, P20-DA017589, and T32-MH018931 and by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development.

The authors thank the study participants who so generously committed their time to the project over the years and the dedicated staff of the Wisconsin Study of Families and Work.

Footnotes

Factor analysis of the Ruminative Response Scale (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) has revealed three factors: brooding, reflection, and depression (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). The depression items overlap in content with depressive symptoms and are not recommended. The brooding subscale has been found to reliably predict depressive symptoms and other maladaptive consequences of rumination in adolescent samples (e.g., Burwell & Shirk, 2007).

The symptom levels of the present sample appear to reflect an average level of distress, in line with other community samples. Although clinical cut-offs have been established for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire with younger samples, they have not been established for the adolescent version used in the present study. However, a sub-sample (n = 234) of these participants completed a structured clinical interview at age 18: 36% met criteria for a current or lifetime history of an internalizing disorder, suggesting this sample may reflect a typical level of distress found in epidemiological studies (e.g., Kessler et al., 2005). Similarly, the participants in the present study reported using alcohol a few times per month in Grade 11, which is consistent with other same-age community samples (e.g., Thompson et al., 2014)

Contributor Information

Lori M. Hilt, Department of Psychology, Lawrence University

Jeffrey M. Armstrong, Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Marilyn J. Essex, Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JA, Ruttle PL, Burk LR, Costanzo PR, Strauman TJ, Essex MJ. Early risk factors for alcohol use across high school and its covariation with deviant friends. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:746–756. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton PC. The relation of coping strategies to alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences in a college sample. Addiction Research and Theory. 2004;12:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Burk LR, Armstrong JM, Park JH, Zahn-Waxler C, Klein MH, Essex MJ. Stability of early identified aggressive victim status in elementary school and associations with later mental health problems and functional impairments. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:225–238. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9454-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RA, Shirk SR. Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: Associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms and coping. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:56–65. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Dickson KS, Anderson NL, Neal DJ. Negative repetitive thought and college drinking: Angry rumination, depressive rumination, co-rumination, and worry. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35:142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Stice E, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent alcohol use and peer alcohol use: A longitudinal random coefficients model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:130–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson SI, Graham JW, Piccinin AM, Hansen WB. Resistance skills training and onset of alcohol use: Evidence for beneficial and potentially harmful effects in public schools and private Catholic schools. Health Psychology. 1995;14:291–300. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Dealing with missing data in developmental research. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ The MacArthur Assessment Battery Working Group. The confluence of mental, physical, social, and academic difficulties in middle childhood. II: Developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:588–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Comparing conditional effects in moderated multiple regression: Implementation using PROCESS for SPSS and SAS. 2014 White paper downloadable from http://www.afhayes.com/public/comparingslopes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Early family context and development of adolescent ruminative style: Moderation by temperament. Cognition and Emotion. 2012;26:916–926. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.621932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Cha CB, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:63–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Pollak SD. Getting out of rumination: Comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1157–1165. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Klein MH, Essex MJ, Clark R. Maternity leave and women’s mental health. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:257–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Replication Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Aldao A, Wisco BE, Hilt LM. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor underlying transitions between internalizing symptoms and aggressive behavior in early adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:13–23. doi: 10.1037/a0035358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic risk factor in depression and anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2011;49:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA. Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: Tests of gender differences. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;16:391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM. Possible contributors to the gender difference in alcohol use and problems. Journal of General Psychology. 2006;133:357–374. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.357-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Watkins ER. Heuristics for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: Explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:589–609. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD. Predicting serious delinquency and substance use among aggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:529–537. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:1171–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Borge AHI. The timing of middle-childhood peer rejection and friendship: Linking early behavior to early-adolescence adjustment. Child Development. 2007;78:1037–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Wang S. False consensus and adolescent peer contagion: Examining discrepancies between perceived and actual reported levels of friends’ deviant and health risk behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:293–306. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rood L, Roelofs J, Bogels SM, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schouten E. The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JAJ, Koenig LJ. Response styles and negative affect among adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1996;20:13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Stockwell T, Leadbeater B, Homel J. Association among different measures of alcohol use across adolescence and emerging adulthood. Addiction. 2014;109:894–903. doi: 10.1111/add.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wade NG, Vogel DL, Yu-sin Liao K, Goldman DB. Measuring state-specific rumination: Development of the rumination about an interpersonal offense scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER, Mullan E, Wingrove J, Rimes K, Steiner H, Bathurst N, Scott J. Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for residual depression: Phase II randomized controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;199:317–322. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willem L, Bijittebier P, Claes L, Raes F. Rumination subtypes in relation to problematic substance use in adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50:695–699. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. Peer and adolescent substance use among 6th-9th graders: Latent growth analysis of influence versus selection mechanisms. Health Psychology. 1999;18:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]